Among the more interesting items coming out of the XXVIII General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in Beijing is news of a circumbinary system containing two planets. We’ve seen circumbinary worlds before — Kepler-16b is a planet orbiting not one but two stars, as are Kepler-34b and Kepler-35b. There was a time that the idea of a planet orbiting two stars, as opposed to orbiting one or the other of two stars in a binary system, seemed unlikely. Now we have a multiple-planet system in exactly this configuration.

It’s an interesting one, too. Some 4900 light years from Earth in the constellation Cygnus, the two stars orbit each other roughly every 7.5 days. One of the stars is fairly similar to the Sun, though about 15 percent less bright, while the other is an M-dwarf about a third of Sol’s size and 175 times fainter. Of the two planets, one — Kepler-47b — is three times the diameter of Earth and eight times its mass, orbiting the twin stars every 49 days. The outer planet — Kepler-47c — catches the eye because it orbits the stars every 303 days, placing it within the twin stars’ habitable zone.

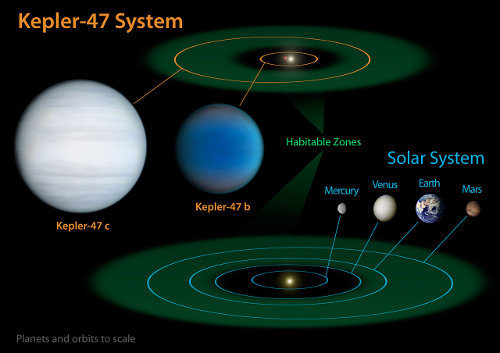

To be sure, this looks to be a gas giant a bit larger than Uranus in size, with about 20 times the Earth’s mass. While not itself a candidate for habitability, its placement allows speculation that an exomoon around it could potentially hold life. The diagram below relates the Kepler-47 system to our own, with the two newly discovered worlds shown for comparison:

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle.

Jerome Orosz (San Diego State University), lead author of the study, notes the tricky nature of the observations that revealed the two worlds:

“In contrast to a single planet orbiting a single star, planets whirling around a binary system transit a moving target. The time intervals between the transits and their duration can vary substantially, from days to hours, and therefore the extremely precise and almost continuous observations with Kepler space telescope were fundamental.”

As this IAU news release notes, the loss of light caused by the eclipse is tiny. While Venus, for example, blocked out about 0.1 percent of the Sun’s surface during its most recent transit in June, Kepler-47b and c blocked out 0.08% and 0.2 percent respectively. Ground-based observations at McDonald Observatory (University of Texas at Austin) backed the Kepler data as the researchers studied the properties of this system. Michael Endl and colleagues studied the binary star with the 9.2-meter as well as the 2.7-meter instruments at McDonald.

“It’s Tatooine, right?” said Endl. “But this was not shown in Star Wars.” The astronomer was referring to the highly variable daylight that would fall upon a planet orbiting two stars. In fact, measurements of the stellar orbits told Endl’s team that daylight on the two planets would vary by a large margin over the 7.4 day period that the stars needed to complete their orbits. A closer look at the McDonald Observatory work can be found in this UT-Austin news release.

Meanwhile, planet hunter Greg Laughlin (UC-Santa Cruz) has this to say:

“The presence of a full-fledged circumbinary planetary system orbiting Kepler-47 is an amazing discovery. These planets are very difficult to form using the currently accepted paradigm, and I believe that theorists, myself included, will be going back to the drawing board to try to improve our understanding of how planets are assembled in dusty circumbinary disks.”

Indeed. We now know that close binaries can host not just single planets but complete planetary systems. The paper is Orosz et al., “Kepler-47: A Transiting Circumbinary Multiplanet System,” published online in Science August 28, 2012 (abstract / preprint).

The paper’s on arXiv: 1208.5489.

Odd — I couldn’t find it there just half an hour ago! Thanks for spotting it. I just included it in the main text.

So Chesley Bonestell’s paintings of double stars, as seen from the surfaces of hypothetical planets in Willy Ley’s 1964 book “Beyond the Solar System,” were perfectly valid depictions…that is very fitting.

A gas giant in a star’s HZ will almost always be bad news for habitable planets around the star. It’s too bad that they picked this lazy PR angle to tout, when there are more interesting (and important) features in this system.

The article itself only makes a (correctly) circumspect passing comment about moons:

“Although the definition of the habitable zone assumes a terrestrial planet atmosphere which does not apply for Kepler-47 c, large moons, if present,

would be interesting worlds to investigate”

Far, far more interesting:

– These planets formed around what is in effect a short period spectroscopic binary, which opens up yet another category of star systems that can sustain planets.

– The stars are slightly metal deficient, yet them managed to produce (at least) two planets.

It would be great if we could find closer, similar binary star planetary systems that could be examined in more detail, especially if the planetary atmospheres can be observed spectroscopically. Are they dry? (one possible complication of binary system planets) Are the orbits stable over billions of years?

I don’t think this impacts the search for planets in the Alpha Centauri system by much, since the planets around Kepler 47 effectively formed around a single star (dynamically), so it would be comparing apples to oranges.

I’m also waiting for the lazy science PR trifecta:

“Could the recently discovered distant gas giant around Flatulino-7 have Earth-sized habitable moons full of He3? We could mine it using FTL neutrinos!”

Another puzzle for current planet formation theory. I’m sure there will be more puzzles forthcoming. “When the bird and the book disagree go with the bird.”

Forget Kepler-38 system…

Kepler-38: the Galaxy’s Count of Binary Stars with Planets is Increasing

http://kepler.nasa.gov/news/nasakeplernews/index.cfm?FuseAction=ShowNews&NewsID=225

Possibly one of the most important/significant observations Kepler has made to date….

The human eye and brain adjust for the hue of the background to which they are exposed. I have heard that the effect is strong enough such that our colonists around even the reddest stars would notice no difference, but I’m wondering if these twin star worlds would be an exception.

If such systems turn out to be common and stable, I can’t help but notice that their planets should spiral outward slightly and wonder how much, in the typical situation, this would compensate for the natural brightening of the main star over time.

Once again the Kepler people minimise/ignore previous similar discoveries. There are several candidate circumbinary planets around post-common envelope binaries discovered through eclipse timing, including a few two-planet systems. Of these, the 2:1 resonant system around NN Serpentis does appear to meet the requirements of dynamical stability as determined by follow-up studies.

While I agree that the Kepler discoveries are certainly very interesting, the decision to ignore these previous discoveries does leave something of a bad taste in the mouth.

@Rob Henry – Unless you’re talking about carbon stars or brown dwarfs,

the light from an M dwarf won’t be much redder than sunlight – at least to the human eye. A tungsten bulb temperature is about 3700K, which is roughly the surface temperature of an M0V star. Even an M9V star at around 2300K would look yellowish. The Kepler 47 stars probably appear as a dim “yellowish” star next to a bright “white” primary.

Close binaries like this are fascinating, because the orbiting planets will mostly just “feel” them as a single star. When the more massive of the pair starts evolving off the main sequence, the two stars can start to interact, and that’s when things “get real”.

i heard by the last Kepler update on space.com that this spring they might find a earth like planet that has a orbit just like the sun in the habitable zone. When are they going to release the next Kepler update ?

It would be interesting to learn the threshold values in AU for closest approach (periastron) of both component stars of a binary, for:

– minimum distance for having planets around both components;

– minimum distance for having planets around one component;

– maximum distance for having circumbinary planets.

I suspect that there will appear to be a gap between the second and the third situation, where the distance between both components is too small to allow planets around either (S-planets in Kepler terminology), but too great to allow circumbinary planets (P-planets in Kepler terminology).

I agree FrankH that yellow seems the most likely colour based on our experience with incandescent lights, but the most yellow I have noticed those lights is through peoples windows at dusk when there is still enough light to see most other objects in natural light. Since the natural light at dusk is already reddened, I am wondering if that experience implies that such a contrasted new red sun might appear very yellow, or even slightly orange.

Perhaps it is always the colour of the sky on our planets that is most important here, which (judging by Earth, Venus and Mars), can vary dramatically.

And related news:

A superearth has been found in the habitable zone of a red dwarf star:

http://www.dailygalaxy.com/my_weblog/2012/08/getting-closer-new-superearth-found-in-red-dwarf-habitable-zone.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed:+TheDailyGalaxyNewsFromPlanetEarthBeyond+(The+Daily+Galaxy+–Great+Discoveries+Channel:+Sci,+Space,+Tech.)

@Ronald:

I have read that circumbinary planets are possible whenever a planet is further than ~4-5 times the maximal distance between the two stars, so there is no clear-cut “maximum distance for having circumbinary planets”. The Alpha Centauri planet searches show that the “minimum distance for having planets around both components” is believed to be below 11.2 AU. I expect that the values for your first and second case are essentially the same – planets’ masses are negligible compared to their star’s, so they won’t perturb close orbits around the other star.

Why do you expect a gap between your 2nd and 3rd situation? There might also be an overlap, i.e binary stars that have both circumbinary planets and planets orbiting just one star (with a large disstance inbetween without planets, of course). That would be a truely weird system…

@henk:

I think they no longer expect to find an Earth-like planet in the habitable zone around a Sun-like star so soon; since stars have turned out to be “noisier” than expected, the Kepler team needs much more than 3 transits to confirm an Earth-sized planet, so it may still take years to find a “second Earth” around a Sun-like star, unfortunately.

What they might find earlier (or already have found, actually) would be an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone around a lighter star (e.g. a red dwarf), which would transit much more often than once per year. That they have not yet announced such a planet does not bode too well for me…

Holger,

thanks.

However:

“circumbinary planets are possible whenever a planet is further than ~4-5 times the maximal distance between the two stars, so there is no clear-cut “maximum distance for having circumbinary planets””.

I would still expect some kind of maximum distance between the components, beyond which only ‘S-planets’ are possible and not (also) circumbinary. This would be the consequence of the (aggregation) formation process of planets and the extent of the protoplanetary dust disc.

“I expect that the values for your first and second case are essentially the same – planets’ masses are negligible compared to their star’s, so they won’t perturb close orbits around the other star”

True, but the stars’ masses may perturb each other’s planets, and if the mass of one component is significantly greater than that of the other, the larger star may perturb the smaller star’s planets but not the other way around, or am I seeing this wrong?

“Why do you expect a gap between your 2nd and 3rd situation?”

The 2nd situation is most likely true for Newtonian mechanical reasons: below a certain distance no S-planets are possible because they will always be perturbed.

There will be a gap, if and only if, the 3rd situation distance (D3) is (significantly) smaller than 2nd situation distance (D2).

E.g. if D2 is 10 AU, i.e. no S-planets for binary stars with minimum distance below 10 AU, and D3 is 3 AU, i.e. no P-planets for binary stars with maximum distance above 3 AU, then this implies that binaries with separations between D2 and D3 (i.e. between 3 and 10 AU in the example) will have no planets at all.

Of course the gap may be a relative paucity, instead of complete absence.

You raise the interesting question whether S-planets and circumbinary (P) planets are possible in the same system? I would not expect so, but it would be weird indeed.

Ronald,

Su-Shu Huang’s ” Life-Supporting Regions in the Vicinity of Binary Systems”

(full paper here: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/40673644 or here:

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1960PASP…72..106H) looked into stable orbits around a variety of binary systems. The work is from 1960 (and some of the ideas are dated), but the work is still useful.

@Rob Henry

Since a red dwarf (or almost any other star) is a good approximation of a black body, a red dwarf next to a sun-like star would look yellowish or orange-ish high up in the sk . Imagine another black body approximation – an incandescent bulb – left on and in bright sunlight. It’ll look distinctly yellow.

At dusk, it’ll look as red (or slightly redder) as the Sun because of scattering.

@Holger said:

“Why do you expect a gap between your 2nd and 3rd situation? There might also be an overlap, i.e binary stars that have both circumbinary planets and planets orbiting just one star (with a large disstance inbetween without planets, of course). That would be a truely weird system…”

well a least we know that binary stars can have Circumprimary,circunsecondary and circumbinary protoplanetary disk in the same binary system:

look at the SR24 Binary Star System

Direct Imaging of Bridged Twin Protoplanetary Disks in a Young Multiple Star

http://phys.org/news180107005.html

Could planets Form in this Protoplanetary Disks? well by the Circumbinary (P type orbit) ans S type of planet orbits I expect it

Ronald,

you’re welcome.

“I would still expect some kind of maximum distance between the components, beyond which only ‘S-planets’ are possible and not (also) circumbinary. This would be the consequence of the (aggregation) formation process of planets and the extent of the protoplanetary dust disc.”

If there is a “fixed” upper limit for the extent of the protoplanetary dust disc, this would indeed give such an upper limit. I don’t know if there is one; planets exist out to 1000s of AU around some stars…

You’re right that larger stars perturb more than smaller ones, so there will be more binary systems in situation 2 than in situation 1. But the _minimum_ value for 1 would be reached for two same-sized stars, and thus be the same as that for 2, I think.

@Daniel:

Thanks for that link. So a similarly weird planetary system similar to SR24 seems also possible to me…

Paul,

this news is just in, and truly fascinating, some excerpts for your information, you can just delete this comment. It is gradually becoming more and more clear that subtle differences in elemental abundances can determine the composition of a star’s planetary system and its long-term habitability;

Stellar makeup impacts planet habitability,

“A new study by Arizona State University researchers suggests that the host star’s chemical makeup also can impact conditions of habitability of planets that orbit them. The team’s paper, published in the August issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters, demonstrates that subtle differences in a star’s internal chemistry can have huge effects on a planet’s chances of long-term habitability.”

“The team’s study indicates that a greater abundance of oxygen, carbon, sodium, magnesium and silicon should be a plus for an inner solar system’s long-term habitability because the abundance of these elements make the star cooler and cause it to evolve more slowly, thereby giving planets in its habitable zone more time to develop life as we know it.”

“The largest changes arise from variation in oxygen. The stellar abundance of oxygen seems crucial in determining how long planets stay in the habitable zone around their host star”.

https://asunews.asu.edu/20120906_young

Hi Paul,

Love your work, it gives me great enjoyment to read.

I not a student of astronomy nor is it my field of work.

It is just a great interest of mine.

I was wondering if you could answer me this:

How would the radiation be in the habitable zone of a binary system?

WOuld it allow for life to develop? What about the increased amount of solar storms?

I am aware that a class M star is very faint, and therefore does not emit as much heat or radiation.

Also would a moon of a gas giant be able to support life like in avatar with the radiation the giant would give off?

Thanks for the kind words, Daniel! I don’t see any reason why radiation would be a problem in the habitable zone of a binary system in terms of stopping life from developing. A red dwarf star, though, is always problematic because of its flare activity, and that could either be a show-stopper or, conceivably, an evolutionary driver. So I’d be more worried about a planet in the habitable zone of a red dwarf than I would about a circumbinary planet per se. Everything would depend upon the type of star and the system’s configuration, etc.