Although it originally ran in the January, 1944 issue of Astounding, I first ran into A.E. Van Vogt’s “Far Centaurus” in a collection of short stories called Destination: Universe (New York: Signet Books, 1952). It would be hard today to re-create the power of the story’s opening, so imbued have we become with reality-stretching concepts, but “Far Centaurus” remains the ultimate illustration of the starship paradox: why send a slow ship when a faster one will surely be built that will one day overtake it?

Van Vogt’s crew arrives in Alpha Centauri space only to find that there is an inhabited planetary system waiting for them, one settled long after their departure from Earth by the much faster ships that were built later. The dialogue is a bit bumpy and the science occasionally awry (van Vogt seems to think there are four, rather than three Centauri stars, for example), but the story has retained its power to this day.

Van Vogt’s crew arrives in Alpha Centauri space only to find that there is an inhabited planetary system waiting for them, one settled long after their departure from Earth by the much faster ships that were built later. The dialogue is a bit bumpy and the science occasionally awry (van Vogt seems to think there are four, rather than three Centauri stars, for example), but the story has retained its power to this day.

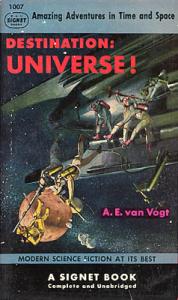

Image: The first paperback edition of Destination: Universe. Although “Far Centaurus” leads off the collection, the book is filled with other worthwhile stories, most of them from Astounding. They include “The Enchanted Village,” “A Can of Paint,” “The Monster” and “Dormant.” The cover of this 1952 edition was by Stanley Meltztoff.

I remember talking to Gregory Matloff, author of the indispensable The Starflight Handbook (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1989), about “Far Centaurus” when we met at Marshall Space Flight Center. Calling it a ‘terrific story,’ Matloff discussed it in terms of Robert Forward’s thinking:

“Bob had a couple of concepts of technological advancement,” Matloff said. “He had a famous plot of the velocity of human beings versus time. And he said if this is true, and you launch a thousand-year ship today, in a century somebody could fly the same mission in a hundred years. Theyre going to be passed and will probably have to go through customs when they get to Alpha Centauri A-2.”

The fascinating question becomes, just when do you launch? A 1,000-year ‘ark’ mission, a so-called ‘generation ship,’ would have to move at 260 AU per year to make the crossing, and according to Matloff, is forseeable using sail technologies and materials that are being developed now. Would we launch such a mission, or would we demand a different standard, such as a mission that could be completed in a single human lifetime? And the suspicion arises that both types of mission might be tried, the “Far Centaurus” paradox notwithstanding.

I’m reminded of what NASA sail expert Sandy Montgomery said about manned missions at the same meeting at MSFC: “The whole human race won’t go; some subgroup will. I think of the 14-year old boys that signed on as cabin boys in the clipper ships. They had to go from New York to San Francisco, around Cape Horn and then back; it took years and years. They left everything that was their life behind, and as they sailed they became adults. They spent most of their lives on that trip, and gave up everything that this crew would have to. So this is not a new issue. It’s a problem some people have already faced into.”

The broader question remains: how do we as a culture view multi-generational projects, and do we have the will and capability to build for futures we ourselves will never see? The question is hardly idle in a time that seems paralyzed by short-term thinking, and the answer may determine our legacy.

I remeber reading Far Centaurus 5 decades ago and it left a great impression in my mind of the vastness that must be space and the rigors undertaken to explore it. That the planets were named pelham etc……….

just a great story

I first read Far Centaurus in 1989. It is nothing short of amazing how long it has held up. Van Vogt’s characters have a reality to them that few SF authors ever achieve, and he imbues them with genuine feeling and personality in a very short story. He gets it right by making the story about human beings not just ideas. The end is exactly as long as it needs to and feels transcendent despite the story’s length. The narrator has a vast emotional tapestry laid out in so few words. “A kiss for the ugly one too…”

I read Far Centaurus in 1959 when I was a junior in high school. Van Vogt’s style and ability to convey the magnitude and profundity of the 500 year trip to Alpha Centauri, made a deep impression on me. That same year, I also read Robert Heinlein’s Universe and Common Sense, and Brian Aldis’ Starship. I became imbued with the desire to see interstellar travel made real. It was stories like these that helped steer me to a career in the sciences and technology (Earth Sciences, Computer Science). My only regret is that I’ll probably not live to see the first ships from Earth set off for the stars.

It is one of the first SF short stories I remember reading, perhaps a little before 1970 when I was 14 and in a Danish translation. It made a tremendous impression right from the first sentence. Let me see: “I woke up with a start, and thought: how is Renfrew taking it?”. Something like that. Lol, must be a decade or more I read it last time. I have an old-old US collection somewhere I ‘ll go check.

Steffen, ‘Far Centaurus’ was one of the first SF stories I can remember reading, too, and it left an indelible impression! To this day, I can look back at that reading with pleasure and call up just a bit of the same wonder that hit me then.

I rember reading ‘Far Centaurus” in an anthology book as well, and remember it fondly. What stuck with me was the vivid imagery of the ship that got too close during one of the ‘waking moments’ of the 500 year journey, as well as the mind-boggling concept of atoms having ‘personalities’. That was a good way for Van Vogt to convey the fact that science in 500 years will be as incomprehensible to us as trying to explain how an iPhone works to someone from the 1500’s.

If you use “sail” technologies when you hit the now theoretical “shock zone” wouldn’t your ship stall?