I discovered Karl Schroeder’s work when I was researching brown dwarfs some years ago. Who knew that somebody was writing novels about civilizations around these dim objects? Permanence (Tor, 2003) was a real eye-opener, as were the deep-space cultures it described. Schroeder hooked me again with his latest book — he’s dealing with a preoccupation of mine, a human presence in the deep space regions between ourselves and the nearest stars, where resources are abundant and dark worlds move far from any sun. How to maintain such a society and allow it to grow into something like an empire? Karl explains the mechanism below. Science fiction fans, of which there are many on Centauri Dreams, will know Karl as the author of many other novels, including Ventus (2000), Lady of Mazes (2005) and Sun of Suns (2006).

by Karl Schroeder

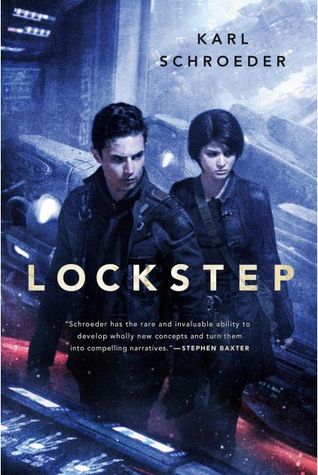

My newest science fiction novel, Lockstep, has just finished its serialization in Analog magazine, and Tor Books will have it on the bookshelves March 24. Reactions have been pretty favourable—except that I’ve managed to offend a small but vocal group of my readers. It seems that some people are outraged that I’ve written an SF story in which faster than light travel is impossible.

I did write Lockstep because I understood that it’s not actual starflight that interests most people—it’s the romance of a Star Trek or Star Wars-type interstellar civilization they want. Not the reality, but the fantasy. Even so, I misjudged the, well, the fervor with which some people cling to the belief that the lightspeed limit will just somehow, magically and handwavingly, get engineered around.

This is ironic, because the whole point of Lockstep was to find a way to have that Star Wars-like interstellar civilization in reality and not just fantasy. As an artist, I’m familiar with the power of creative constraint to generate ideas, and for Lockstep I put two constraints on myself: 1) No FTL or unknown science would be allowed in the novel. 2) The novel would contain a full-blown interstellar civilization exactly like those you find in books with FTL.

Creativity under constraint is the best kind of creativity; it’s the kind that really may take us to the stars someday. In this case, by placing such mutually contradictory — even impossible — restrictions on myself, I was forced into a solution that, in hindsight, is obvious. It is simply this: everyone I know of who has thought about interstellar civilization has thought that the big problem to be solved is the problem of speed. The issue, though (as opposed to the problem), is how to travel to an interstellar destination, spend some time there, and return to the same home you left. Near-c travel solves this problem for you, but not for those you left at home. FTL solves the problem for both you and home, but with the caveat that it’s impossible. (Okay, okay, for the outraged among you: as far as we know. To put it more exactly, we can’t prove that FTL is impossible any more than we can prove that Santa Claus doesn’t exist. I’ll concede that.)

Generations of thinkers have doubled down on trying to solve the problem, unaware that the problem is not the same as the issue. The problem — of generating enough speed to enable an interstellar civilization — may be insoluble; but that doesn’t mean the issue of how to have a thriving interstellar civilization can’t be overcome. You just have to overcome it by solving a different problem.

The problem to solve doesn’t have to do with speed (or velocity, for you purists), but rather with duration.

Enter Lockstep. In the novel, all worlds, all spacecraft and all habitats participating in a particular civilization use cold-sleep technology “in lockstep:” the entire civilization sleeps for thirty years, then simultaneously wakes for a month, then sleeps for another thirty years, etc. All citizens of the lockstep experience the same passage of time; what’s changed is that the duration of one night per month is stretched out to allow time for star travel at sublight speeds. In the novel I don’t bother with interstellar travel, actually; the Empire of 70,000 Worlds consists almost entirely of nomad planets, wanderers populating deep space between Earth and Alpha Centauri. Average long-distance travel velocity is about 3% lightspeed, and ships are driven by fission-fragment rockets or ‘simple’ nuclear fusion engines.

The result is a classic space opera universe, with private starships, explorers and despots and rogues, and more accessible worlds than can be explored in one lifetime. There are locksteppers, realtimers preying on them while they sleep, and countermeasures against those, and on and on. In short, it’s the kind of setting for a space adventure that we’ve always dreamt of, and yet, it might all be possible.

Cold sleep technology is theoretical, but unlike FTL, it’s not considered out of the question that we could develop human hibernation. It’s a bio-engineering problem, and probably admits of more than one solution. It’s an easier problem to solve than FTL, in other words. And by solving it, and using locksteps, we have a universe where travelers can go to sleep at their home port, wake up the next day at a world that could be light-years away, spend some time there and, when they return, find that exactly the same amount of time has passed at home. Locksteps give you the effect of FTL, without requiring FTL.

I won’t go into all the implications—that’s what the novel’s for. But, to circle back to the idea of creative constraint, by requiring an FTL-like civilization without FTL, I stumbled into a whole new universe. In the world of Lockstep, there are Sleeping Beauty-like tales, a version of the Twin Paradox, and an even stranger paradox in which the newest immigrants to the lockstep have the longest history with it… It’s no exaggeration to say that many books could be written in this world without exhausting its possibilities. Maybe I’ll write more of them myself.

Meanwhile, the idea’s out there. It’s a bit crazy, but it’s a possible solution to an issue, that avoids having to solve an impossible problem.

A constraint that gives us a way to reach the stars.

LJK:

Cryptobiosis is not life extension. Let’s not mix up the two just because they happen to be discussed in the same thread. As I have pointed out, the suspension of maintenance and repair during cryptobiosis may actually be life-shortening in effect. Life extension is the inhibition of mechanisms of aging, and neither requires nor is likely to be helped at all by any type of hibernation. The two are separate problems, pretty much, with independent solutions, if any.

Most forms of hibernation short of cryptobiosis will probably keep the mechanisms of aging going. In cryptobiosis, you have no aging, but you do have decay due to lack of repair. For this reason, I think that the time spent in any form of suspension will be lost from one’s life, for the most part. In this indirect way the two are related: If you are longer-lived, you can more easily afford the time in suspension.

I wonder if Karl Schroeder is familiar with Philip Jose Farmer’s Dayworld. I don’t recommend the book, but the central idea is an Earth-bound version of Lockstep.

Here is a description from the author’s website: “The population of earth has increased to the point where people are only given one day a week to live. The other six days they are ‘stoned’, placed in suspended animation until their day comes around. You share your apartment with six people you never meet and your job with six other people you will never see. Daybreakers however, live a different life with a different name, job, wife, everything, each day of the week.”

Lockstep reminds me of an ’80’s novel called “Dayworld” where to conserve resources, people had to hibernate 6 days out of 7.

It sounds like a fun solution to the Star Trek without FTL problem, but like others I see too many temptations to cheat. The only way I could see it working is if everyone was living gypsy style in mobile space colonies.

On the other hand there has been a lot of great SF written without FTL, one of the interesting aspects of this is what such civilizations do with having access to the power levels that “fast” non-FTL spaceflight requires.

Rebelliously I will ask who would prefer Lockstepper to RealTimer? No brainer – rock and roll :). However, cryosleep allows you to view the far future if managed right. So does relativistic acceleration away from and back to Earth. So have the best of both worlds – a fleet of good time ships which return to Earth every one of their years where one hundred years on Earth has elapsed each time. A ship decade is an Earth millenium. One can have the best of both worlds while staying awake and learning what one will. Each visit to Earth involves picking up the latest tech and generally touching base.

Sounds like a great life.

I think that as the lockstep process was initially developed, and as it became clear that it didn’t affect the health of the sleepers any more than regular sleep, it might become very attractive as a way of life. There would be, for a while, a gigantic gain for lockstepers compared to others, as they reaped the benefit of compound interest without any work of their part. It would be a natural progression for groups of people to start locksteping together, in order to keep relationships with contemporaries alive, rather than the loneliness of awaking ‘out of synch’ with the rest of humanity. This gain would be reduced as more and more people went into lockstep mode, but in an orderly society with private property and money, the lockstepers might indeed provide a more interesting way of life than the realtimers.

I can also see locksteping starting with the old and the sick, as they wait for adequate technologies to help them improve their quality of life. This is already apparent with the cryogenics idea; but since it still requires death to be implemented, it’s not all that attractive for the moment!

Michel Lamontagne: If all the process did was not “affect the health of the sleepers any more than regular sleep”, you would not find many people do it, as it would dramatically shorten their waking lives. The concept really only works if you postulate a method that miraculously suspends aging while you sleep, giving you roughly the same amount of time awake spread over a longer period.

Unfortunately, this is not very plausible, biologically. Unless, that is, you are talking all-out, deep-freeze cryogenics. Then, the trick is keeping the repeated freeze-thaw cycles from killing you faster than aging will, in the long run.

Thinking this would also require some pretty advanced AI. After all, if the entire civilization sleeps then who maintains the infrastructure?

If all humans on earth were to be grabbed out of time and flung thirty years in the future we would have to spent decades, let alone a month, just to rebuild. Road, buildings, power plants, vehicles, …. It would all have to be either replaced, or at least have massive repairs done.

In such a universe you would also have to stockpile food so people didn’t starve upon time restarting. Unless you had such AI the growing season for crops could be at most a month.

But then, if you got star travel you probably got AI of such a level.

Even at sub light speed, mass becomes and extreme problem. You either have to travel so slowly that even nearby stellar hops can take centuries or you have to use vast amounts of energy to accelerate to even a small fraction of light speed. One concept that is relatively unexplored in fiction is the idea of interstellar colonization based on information rather than matter. Information travels at the speed of light and can be sent with relatively few resources. The problem is that there is no one there to receive it. One solution is to send vast numbers of tiny automated seeds. These could be very small, perhaps the size of a base ball. They would contain millions of nano robots and the smarts to gather local resources and eventually build a receiving station on whatever planet they happen to land on. Once in communications with the galactic empire, instructions for building more seed factories could be sent. While it would be possible to send digital copies of humans to the colonized worlds, this does not make much sense. It is more likely to be a post singularity AI that would be sending copies of itself to the stars.

My first thought was, why would everyone agree to do this for no apparent reason?

My second thought was that it would be for the same reason you the author would do it: It allows for a cohesive interstellar civilization. A society that doesn’t go lockstep functions hundreds of times faster; they could have huge advantages in industrial production and scientific progress… but they will forever be restricted to a single system. The same goes for anyone who might rebel from a lockstep empire: They experience a renaissance, freed from the bounds of lockstep they suddenly feel very powerful and see a bright future for themselves as the new lords of space. It never happens. The rebellion can’t spread for the same reasons you can’t have a conventional interstellar empire. The lockstep empire, despite being relatively ponderous, is still far larger and more powerful and eminently able to quash the rebellion, or just wait for such ideas to peter out.

I honestly can’t see any civilization willfully enter a lockstep. To me it sounds more impossible than FTL. Why would any world do it? Trade? What could earth trade with dark worlds? To live 50 years in a lockstep world would take 18.000 years of real time. How much could a civilization advance in that time? How many technologies could be discovered? It makes no sense at all.

If someone offered you the chance to live a decade of time whilst everyone else lives a year, would you take it? Just think of all you could learn in that time…

Thank you so much for writing this book! I’ve been waiting so long for someone to try to make a book like this. Personally, I think FTL travel is extremely unlikely, given the effect it would have on causality. I always imagined that there might be extremely long-lived forms of life that think and act incredibly slowly to our perspective, for whom the distance between stars isn’t as much of an obstacle. We’re kind of pathologically fast and short-lived as individuals, when you consider the scale of the universe. Lockstep is a creative solution, though. I like it!