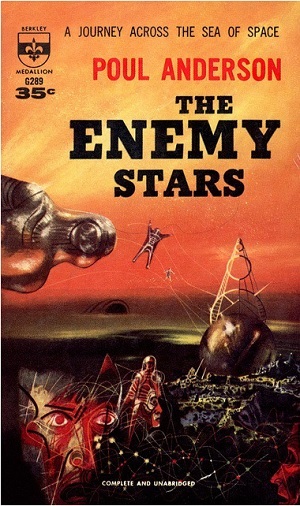

One of the reasons I do what I do is that when I was a boy, I read Poul Anderson’s The Enemy Stars. Published as a novel in 1959, the work made its original appearance the previous year in John Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction as a two-part serial titled “We Have Fed Our Sea.” The reference is to Kipling’s poem “The Song of the Dead,” from which we read:

We have fed our sea for a thousand years

And she calls us, still unfed.

Though there’s never a wave of all her waves

But marks our English dead…

Space was, for Anderson, the new sea, one whose imperatives justify the sacrifices we make to conquer her, and “We Have Fed Our Sea” is a far better title for this work than its book version. Kipling writes:

We were dreamers, dreaming greatly, in the man-stifled town;

We yearned beyond the sky-line where the strange roads go down.

Came the Whisper, came the Vision, came the Power with the Need…

I bought The Enemy Stars at the Kroch’s and Brentano’s bookstore on S. Wabash Avenue in Chicago (this was the flagship store of the chain, and what an astonishing place it was for a book-dazzled boy like me to wander about in). I still have that paperback, and I can remember picking it up because of what was on the back cover:

They built a ship called the Southern Cross and launched her to Alpha Crucis. Centuries passed, civilisations rose and fell, the very races of mankind changed, and still the ship fell on her headlong journey toward the distant star. After ten generations the Southern Cross was the farthest thing from Earth of any human work – but she was still not halfway to her goal…

That was my first encounter with the idea that we might go to the stars in multi-generational ways. But Poul Anderson was always ahead of his time, and this is not a generation ship in the model of, say, Heinlein’s Orphans of the Sky. People do not live out their lives aboard the Southern Cross and hand on the great imperative of the mission to their descendants. Instead, crews in the Solar System are regularly teleported out to the ship.

It’s a wonderful story, and that Kipling reference will put a chill up your spine when you see what Anderson does with it. Baen Books incorporated a later novella called “The Ways Of Love” into its edition of The Enemy Stars in 1987, but I much prefer the unadorned core story. I went back to it this past weekend after writing On the Role of Humans in Starflight on Thursday, having thought for several days about the different ways we approach doing long-term things. Probably if I had read Nelson Bridwell’s just published essay To Be or Not to Be? Mankind’s Exodus to the Stars a day earlier, I would have incorporated it into the Thursday post.

But today will do just as well, for Bridwell’s themes are much to the point, reminding me of generation ships in all their manifestations, as well as generation-spanning projects. Described as a ‘senior machine vision engineer working in manufacturing automation,’ the author sees interstellar flight as a natural and necessary outcome of our space efforts, one that will take millennia and will not require violations of physical law. It is an effort, though, that should not be delayed. Writes Bridwell:

Because starships will not be ready to go for many centuries and interstellar voyages may last for thousands of years, we will want to get started sooner rather than later, initially allocating a small but steady fraction of the space budget to identify the most promising engineering approaches and performing early proof-of-concept experiments when affordable. The first application of this technology will be for unmanned interstellar probes that will conduct close-up reconnaissance of nearby solar systems.

Taken to its outer limit, a long-term perspective on Earthly life tells us that the planet will eventually meet its doom, if in no other way, through the gradual swelling of our parent star. But as Bridwell points out, we’re a long way from not just starflight but even a sustained human presence off this planet. It’s prudent, then, to do whatever we can to minimize the existential risk of something happening in the interim to destroy our species. That might involve accelerating the search for near-Earth asteroids and comets to provide plenty of time to change the trajectories of those in dangerous orbits. It also might involve a heightened awareness of and countermeasures for the kind of pandemic that could cut the population in half, if not worse.

In terms of space, bringing the long-term focus of interstellar thinking into play involves continuing the search for promising nearby solar systems where humans may eventually travel even as we develop the kind of closed-loop life support technologies that would sustain human crews over the duration of long voyages. The latter aspect receives far less attention than it should, but it is as key a driver as propulsion for figuring out how to make star journeys.

I think Bridwell has it right that an interstellar effort grows directly out of sustained development here in our own Solar System. We will learn the essentials of closed-loop life support by experimenting in places much closer to home than even the nearest star:

Because it is not at all likely that a warm, moist, green, oxygen-rich twin of Earth will be within our reach, the third goal must be learning how to live under less-ideal conditions, such as on the Moon. We should establish manned outposts on the Moon and Mars where we can develop the expertise to efficiently manufacture everything that we need from local planetary materials. Over the course of hundreds of years, as these outposts grow, they will become second homes within this solar system for humanity.

I see this in terms of O’Neill-class colonies that gradually grow in size and sophistication, as well as bases on planetary surfaces. The immediate need is to develop our skills at living in nearby space so that if something does happen to our planet — nuclear war, perhaps, or biological catastrophe — enough colonies will exist to perpetuate the species. Over the course of the next few centuries, creating such self-sustaining populations in space should be within our technological powers, and these will inevitably spread outward as we explore our system’s resources. I find this prospect encouraging because it assumes nothing the laws of physics do not allow.

Bridwell wonders whether our reluctance to think beyond the current moment is not itself a passing phenomenon, perhaps ‘a madness left over from the Cold War.’ I do think it is a cultural phenomenon, though I have no opinions about its origins in 20th Century geopolitics. We make our own values by choosing what to build, what to believe in, and what goals to pursue. A positive perspective is one that protects the home world first while ensuring that unexpected catastrophe cannot destroy our species. It then begins the long process of exploration and settlement that may spread as far as the outer planets, or perhaps the Oort Cloud, or if we have the determination to make it happen, the distant stars Poul Anderson saw as our destiny.

It’s up to us to make it a cultural imperative.

The key technology in Anderson’s story is the mattercaster. If we had such technology today, our starships might be robotic, carrying just the teleport or even just the means to build one locally. It bypasses almost all the issues of human crewed ships, allowing humans to cross pace in an instant. Even within the solar system, it would be a huge advantage, allowing humans to visit places for short durations before returning home.

However, if we are skeptical of mind uploading, we should be even more so of FTL teleportation.

In principle, I do like the idea that the ships are transporters of receivers. These receivers might just convert laser transmitted information of minds into machine hosts, or even full human replication. The trip while actually taking many years would feel instantaneous to the individual. If human minds cannot be sent, then nurtured machine minds can. If the receiver and its antenna can be low mass, this seems to be a very plausible way to economically reach the stars.

When I struggle with a realy hard problem , bordering the impossible (to me that is) , the best way to move forward is very often in a direction that leads me to solve the problem at least twice . ” Plan A” and ”Plan B” is of course a very old and simple idea , but there are a hidden debth to it : analysis of military strategy shows us that it works best when NOBODY knows who’s A and who’s B ..

From this perspektive , it seems to me that we need a REAL plan B , one that is radically different in the way it imagines humans to achieve starflight . My best candidate for this job , is a plan that builds on something close to the worst-possible-scenario . …. How are we going to do it if no comercial industries are establihed in Space , if planetary population reaches an unsustainable level with disastrous consequences , if ideology mutates into an even more virulent strain ?

Very little thought has been given to starflight in such a scenario , perhabs because it appears to be impossible.

One of the few exeptions are Jack Wiliamsons ”Manseed ” where a biggish number of cheap ”manned” spacecraft are sent off , using very limited resources . ..

If you are trying to do the almost-impossible with no money , a lot of taboos have to be broken . …the list is growing every day : nuclear power , genetic engeneering , cloning , animals rights , human rights , climate change and a lot more . ”Plan B” is not going to be popular with the same people who normaly would support plan A , but we need it anyhow .

I agree that, “Bridwell has it right that an interstellar effort grows directly out of sustained development here in our own Solar System.” But unless human lifespans grow to exceed a thousand years, I do not think thousand-year star journeys will ever happen.

O’Neil type colonies may exist by the hundreds or even the thousands before they have proven dependable enough to turn one into a starship. When that happens, it is likely that the mass radiation shielding will be replaced by fusion fuel and the ship will head out at 10-15%c; quick enough to get to Alpha Centauri in 30-45 years.

Slow human expansion into the galaxy at these speeds would be like island-hopping across the Pacific to settle Polynesia, bringing everything needed for colonization in the colony/starship/home. My interest when I was younger was to get to Alpha Centauri, but the vision of Marshal Savage in his non-fiction book ‘The Millenial Project’ is how I see humans colonizing the galaxy.

Until the invention of warp drive, of course.

I remember reading We Have Fed Our Sea in Astounding (1958) and then as The Enemy Stars(1959). I have only become aware Anderson rewrote a portion of the novel for the 1979 release. He straighten out some tortured language as to how his FTL matter transmitter worked by using tachyons.

Poul Anderson was very thoughtful about his physics in his stories , he did have a degree in physics.

What I thought was so clever was how Anderson made an end run on FTL. He must have thought “maybe one cannot project a material mass at FTL speeds but we may be able to signal at FTL speeds”. I am pretty sure James Blish already had the faster than light ultraphone and the instantaneous Dirac transmitter, in Cities in Flight. (Trust Blish to trump himself!) As far as I know , maybe, Anderson was the first to couple matter transmission with FTL transmission of information and STL travel?

I remember thinking “what a cool solution” , send out relativistic ships with matter transmitter receivers /transmitters and you have a World Ship without all the the complications of physiological and logistical cost. Once at destination one could transmit out a colony and also build more Ship-Transceivers.

It could be done at the speed of light too though one introduces relative time effects. I don’t remember a SF story that used Anderson’s idea , could be?

I do remember Clifford Simak’s novel Way Station where a Civil War veteran has maintained a node on a kind of matter transmitter network for a galaxy wide federation of alien civilizations. A Hugo winning novel.

I think there are variants on these by I don’t remember them.

In the 1988 science fiction film They Live, where aliens use Earth and its inhabitants like a third World nation (their explanation), the ETI get around the galaxy using some kind of matter transporter, which we see in use briefly.

However I highly recommend They Live for its messages and cleverness, not its science.

http://vigilantcitizen.com/moviesandtv/they-live-the-weird-movie-with-a-powerful-message/

http://www.theofficialjohncarpenter.com/pages/themovies/tl/tl.html

@ljk – “They Live” Was an extraordinary example of cinema telling the truth under the guise of grade B science fiction. Roddy Piper was cheeky enough to tweet: “They Live is a documentary!! 8:42 AM – 28 Sep 2013”. Of course our rulers are not space aliens, simply ruthless sociopaths.

Of note Club of Rome member Ugo Bardi has just blogged on the decline of human spaceflight:

“I experienced the enthusiasm of the “space age,” starting in the 1960s, and I am not happy to see the end of that old dream. Yet, the data are clear and cannot be ignored: human spaceflight is winding down. Look at the graph, below. It shows the total number of people launched into space each year. As you see, the number of people sent to space peaked in the 1990s, following a cycle that can be fitted reasonably well using a bell-shaped curve (a Gaussian, in this case). We have not yet arrived to the end of space travel, but the number of people traveling to space is going down. With the international space station set to be retired in 2020, it may be that the “space age” is destined to come to an end in a non remote future.”

http://cassandralegacy.blogspot.co.nz/2015/02/the-last-astronaut-cycle-of-human.html

Only reusable rockets and a revolutionary decline in cost to orbit can stop the decline now. SpaceX is trying again today. Long live Elon Musk!

That is a really dubious curve fit, IMO. It also seems unlikely unless we assume newer space nations are going to abandon human spaceflight, which they show no signs of doing.

If low cost access to space is achieved, it would undermine the declining human spaceflight meme. Go SpaceX, go!

Great article/blog with very interesting responses. I clearly agree with need for the emergence of an interplanetary economic infrastructure that will support the launch of humanity into interstellar space sans warp drives , teleportation, wormholes or any other mythical/fantastical forms of space travel. So instead of Star Trek-like expansion, we would expand like the Polynesians across the Pacific ocean or the like the 1st Nations ancestors expanded across the Western Hemisphere. We will be space faring race!

Joy, you really have to consider the source on the blog you reference. It was written by someone who believes the Moon landings were fake (see his last comment). If he believes that, why would he believe interstellar travel was even possible?

His economic analysis is also flawed. Too many to bother with in their blog, and perhaps out of place here, so I will be brief. The data he uses is multi-modal, but he is attempting to treat it as single mode. The Russian commitment to manned space flight has been fairly consistent over the years. The U.S. commitment has followed major projects for manned space flight, and has been fits and starts. U.S. commitment has been plagued by the divide between manned and robotic flights, which is a resource issue, and given the U.S. national debt, a case could be made for eventual abandonment of manned U.S. space flight. But you have to remember the fits and starts. U.S. space policy follows political whim. We could have another start in the future.

Maybe even with SpaceX. They are arriving apparently just when they are needed. However, they are also fully linked to government expenditure and it is unclear how long low interest in manned spaceflight will last.

Paul: Great blog!

There are some reall great questions about the best way for us to reach other solar systems. At this time it looks like we should be able to engineer a solar sail strategy that could allow us to seed other solar systems with a minimum crew on the ships and a major population expansion after we arrive.

Such basic technologies could allow us to expand throughout this galaxy by hitchinghiking (sorry Douglas Adams) via nearby higher-velocity retrograde stars. The name eludes me, but there is one only 10 LY away. Talk about starships!

And if we want to expand to the Andromeda galaxy, all we have to do is wait, because it will come to us.

As our technologies advance over thousands of years, it is possible that better options (colony ships, higher speed travel…) may become possible.

But at the very least, there is hope for our future, provided that we begin to get serious.

There are many in the space community who run with the multi-planetary argument that we need Mars because we think something really bad will probably happens to the Earth. I think that line of reasoning is slightly backwards becasue it will take hundreds of years for us to establish fully self-sufficient, thriving outposts on the Moon and Mars. People underestimate the massive techlological infrastructure that will be required to support basic survivial on other planets.

We need to make sure that “bad news” is simply not an option on this planet for the next thousand years because it will be key to our survivial.

Micky Badgero: I do not think Bardi believes in the “Lunar Landing Hoax”. I read his comment about this as tongue-in-cheek. However, the curve fit is clearly hogwash, and the link to resource depletion contrived.

Best said by Anonymous in the comments there:

“A better measurement of our progress in space could come from total space miles traveled by all vehicles and satellites, total amount of rocket energy expended, total dollars in all space programs (commercial and government), etc. ”

Any of these measures would show something more like an exponential increase in space activity, rather than the imaginary “Hubbert-curve” trend Bardi tries to conjure up.