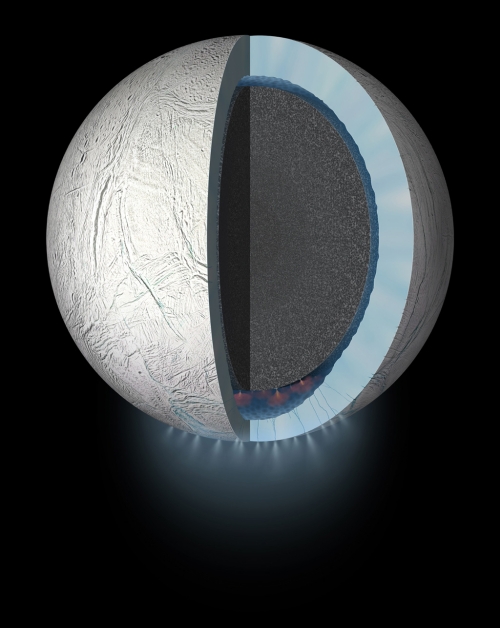

We now pivot from Dysonian SETI to the ongoing exploration of our own system, where lately there have been few dull moments. Today the Cassini Saturn orbiter will make its deepest dive ever into the plume of ice, water vapor and organic molecules streaming out of four major fractures (the ‘Tiger Stripes’) at Enceladus’ south polar region. The plume is thought to come from the ocean beneath the moon’s surface ice, and while Cassini is not able to detect life, it is able to study molecular hydrogen levels and more massive molecules including organics. Understanding the hydrothermal activity taking place on Enceladus helps us explore the possible habitability of the ocean for simple forms of life.

Image: This artist’s rendering showing a cutaway view into the interior of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. NASA’s Cassini spacecraft discovered the moon has a global ocean and likely hydrothermal activity. A plume of ice particles, water vapor and organic molecules sprays from fractures in the moon’s south polar region. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Cassini’s cosmic dust analyzer (CDA) instrument can detect up to 10,000 particles per second, telling us how much material the plume is spraying into space from the internal ocean. Another key measurement in the flyby will be the detection of molecular hydrogen by the spacecraft’s INMS (ion and neutral mass spectrometer) instrument, says Hunter Waite (SwRI):

“Confirmation of molecular hydrogen in the plume would be an independent line of evidence that hydrothermal activity is taking place in the Enceladus ocean, on the seafloor. The amount of hydrogen would reveal how much hydrothermal activity is going on.”

We’re also going to get a better picture of the plume’s structure — individual jets or ‘curtain’ eruptions — that may clarify how material is making its way to the surface from the ocean below. Cassini will move through the plume at an altitude of 48 kilometers, which is about the distance between Baltimore and Washington, DC. “We go screaming by all this at speeds in excess of 19,000 miles per hour,” says mission designer Brent Buffington. “We’re flying the deepest we’ve ever been through this plume, and these instruments will be sensing the gases and looking at the particles that make it up.” Cassini has just one Enceladus flyby left, on December 19.

NASA’s online toolkit for the final Enceladus flybys can be found here.

Meanwhile, in the Kuiper Belt…

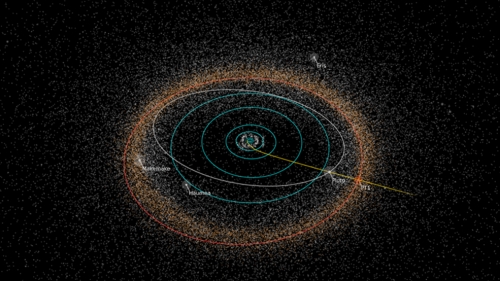

Although its mission at Pluto/Charon has been accomplished, there are a lot of reasons to be excited about New Horizons beyond the data streaming back from the spacecraft. On October 25th, mission controllers directed a targeting maneuver using the craft’s hydrazine thrusters, one that lasted about 25 minutes and was the largest propulsive maneuver ever conducted by New Horizons. The burn, the second in a series of four, adjusts the spacecraft’s trajectory toward Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69.

If all goes well (and assuming NASA signs off on the extended mission), the encounter will occur on January 1, 2019. The science team intends to bring New Horizons closer to MU69 than the 12500 kilometers that separated it from Pluto on closest approach. Two more targeting maneuvers are planned, one for October 28, the other for November 4. Every indication from data received at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory is that the Sunday burn was successful. We now have a new destination a billion miles further out than Pluto.

Image: Path of NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft toward its next potential target, the Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69. Although NASA has selected 2014 MU69 as the target, as part of its normal review process the agency will conduct a detailed assessment before officially approving the mission extension to conduct additional science. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Alex Parker.

Remember that this is a spacecraft that was designed for operations in the Kuiper Belt, one that carried the extra hydrazine necessary for the extended mission, and one whose communications system was designed to operate at these distances. The science instruments aboard New Horizons were also designed to operate in much lower light levels than the spacecraft experienced at Pluto/Charon, and we should have enough power for many years.

Principal investigator Alan Stern commented on the choice of this particular Kuiper Belt object (also being called PT1 for ‘Potential Target 1’) at the end of the summer, noting its advantages:

“2014 MU69 is a great choice because it is just the kind of ancient KBO, formed where it orbits now, that the Decadal Survey desired us to fly by. Moreover, this KBO costs less fuel to reach [than other candidate targets], leaving more fuel for the flyby, for ancillary science, and greater fuel reserves to protect against the unforeseen.”

What we know about 2014 MU69 is that it is about 45 kilometers across, about ten times larger than the average comet, and 1000 times more massive. Even so, it’s only between 0.5 and 1 percent of the size of Pluto, and 1/10,000th as massive. Researchers consider objects like these the building blocks of dwarf worlds like Pluto. While we’ve visited asteroids before, Kuiper Belt objects like this one are thought to be well preserved samples of the early Solar System, having never experienced the solar heating that asteroids in the inner system encounter.

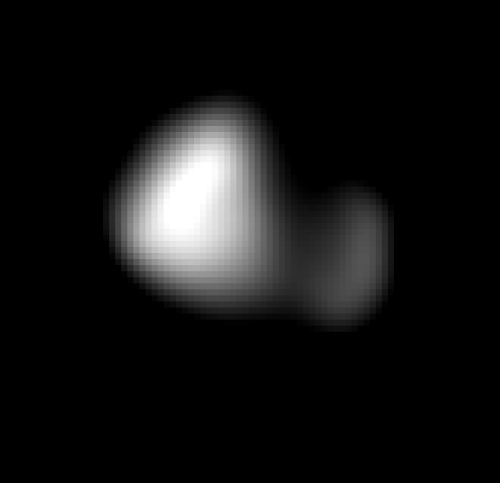

We also have a newly received image of Pluto’s tiny moon Kerberos, which turns out to be smaller and much more reflective than expected, with a double-lobed shape. The larger lobe is about eight kilometers across, the smaller approximately 5 kilometers. Mission scientists speculate that the moon was formed from the merger of two smaller objects. Its reflectivity indicates that it is coated with water ice. Earlier measurements of the gravitational influence of Kerberos on the other nearby moons were evidently incorrect — scientists had expected to find it darker and larger than it turns out to be, another intriguing surprise from the Pluto system.

Image: This image of Kerberos was created by combining four individual Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) pictures taken on July 14, 2015, approximately seven hours before New Horizons’ closest approach to Pluto, at a range of 396,100 km from Kerberos. The image was deconvolved to recover the highest possible spatial resolution and oversampled by a factor of eight to reduce pixilation effects. Kerberos appears to have a double-lobed shape, approximately 12 kilometers across in its long dimension and 4.5 kilometers in its shortest dimension. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

Re: Enceladus, has anyone explained why they think the geysers are mostly in the south pole and not the north?

Looking at Jupiter’s moon IO, I think there is an example where Tidal

Heating is causing Hot spots/Volcanic activity and their distribution is relatively even (albeit not where they were expected on some models).

I cite the above Jupiter example this as a contra factual to the claim that Enceladus ALL of the heating is caused by Tidal effects from Saturn & it’s other moons. The heating seems too localized and frankly at the wrong location for just tidal effects causing geysers/liquid water on Enceladus.

There are only 3 things that I can think of that would release additional heat, a large polar strike from a meteor which contained radioactive elements distributed within. Second possibility is a strike from a meteor or cometary body which contains compounds that react with water/ice. Some energetic examples are molecules of Sodium,Lithium ,Potassium ,Rubidium, Caesium. All of the above would indicate that the heating on Enceladous

is a relatively recent development since there is a limited amount of compounds, and the age of the solar system is 4.5 billions years.

The third option is exobiology possibility. A microscopic form of life hitching a ride on a comet or asteroid. and arriving Enceladus, consuming it’s internal structure and releasing heat. Once again, just how

long would such a life form last before consuming all its “food”. I not

sure if the length of excess heating would be longer than from the

non-biotic heating examples from above.

It will be sad when they destroy Cassini’s, if there is life on-board Cassini and it survived all that space could throw at it surely it should be given the chance to survive if it can, who are we to decide such an enduring organisms fate?

Rant over!

Cassini has been one of the all time great missions. It’s a gift that keeps on giving. Hurrah for Cassini!

A great advantage about these cracks in ice covered worlds is that they are easier access points to the liquid layers below reducing the energy required to get to those oceans considerably. They would also be natural points to test for life without actually having to go deep down.

Thanks for mentioning the low light levels experienced by New Horizons, Paul. It’s been a question on my mind for some time.

The Pluto team did some outreach before close approach, showing earthlings the light levels on Pluto by comparing to certain times after sundown. Dark. And now a billion additional miles, much darker, one can’t help but wonder how those fully illuminated images are captured, particularly by a spacecraft blazing at extraordinary speeds and presumably rotating to keep the subject in focus.. Perhaps someone can point to a fuller explanation of how this is achieved- I’ve not found it yet.

Is it just my immagination, or does the SHAPE of Kerberos bear a STRIKING RESEMBLANCE to Comet 67P! ALSO: Wha if the “Earlier measurements of the gravitational influence of KERBEROS on the other nearby moons” DED turn out to be CORRECT? Could BOTH LOBES be made out of PURE IRON with an icy coating. That would throw theorists into a TIZZY!

@TLDR October 28, 2015 at 12:22

“Re: Enceladus, has anyone explained why they think the geysers are mostly in the south pole and not the north?”

I’m not sure if this is the whole answer but I remember reading of a zero-g bowling-ball angular-momentum analogy for Enceledus and its south-polar plumes. The three holes in the bowling ball represent missing mass and if the ball is spun along any orientation it will re-orient itself, with the holes aligning with the spin axis poles. To me this implied that Enceledus’ icy mantle would have thickness variations with the thinner regions being candidates for plume activity. Once the tiger stripes became dominant they would re-orient to the poles… in this case the South.

Not sure if this is still an accurate model though… maybe there is some evidence to be gleaned whether Enceledus went through this or not.

Thanks, Mark. I saw thinking maybe a comet or asteroid had hit it on that face.

Forces acting on Enceladus conspire to open crack under the poles and close them at the equator. Any rocking motion of the ice-rock mantle would encourage liquid to move upward through those cracks at the poles.

If there are not any active thermal vents causing the eruptions we see on the surface of Enceladus and the eruptions are caused by sublimation, would sublimation still cause any number of heat producing variables where the deepest location of sublimation would occur?