As discussed in yesterday’s entry, being able to work with actual light from distant planets is a major breakthrough. It opens the possibility of studying characteristics like temperature and atmospheric composition, further fusing astronomy with the nascent science of astrobiology. And with the Spitzer Space Telescope’s proven ability to make such observations, we can expect a whirlwind of exoplanetary data ahead.

A few further details from yesterday’s announcements:

A study of the work on HD 209458b, a ‘hot Jupiter’ that orbits its parent star in 3.5 days, ran in today’s online edition of Nature. The paper is Deming, D., Seager, S. et al., “Infrared radiation from an extrasolar planet.” Dr. Sara Seager of the Carnegie Institution, a co-author of the study, provided more about HD 209458b:

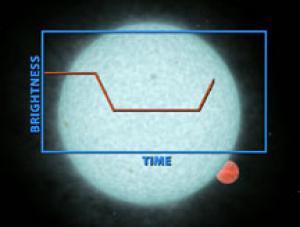

“This planet was discovered indirectly in 1999 and was later found to transit its star–the star dims as the planet moves in front of it during the course of the planet’s orbit. With Spitzer, we first measured the combined light of the planet and star just before the planet went out of sight. Then when the planet was out of view, we measured how much energy the star emitted on its own. The difference between those readings told us how much the planet emitted.”

The result: HD 209458b was found to be a scorching 1,574 F (1130 K). Nature.com’s news site also offers the article “Light from alien planets,” by Mark Peplow, a useful overview.

Other facts: HD 209458b lies 153 light years from Earth in the constellation Pegasus. TrES-1 is 489 light years away in the constellation Lyra. And while yesterday’s entry said that both HD 209458b and TrES-1 orbit stars very much like our sun, this is true only of the former; TrES-1’s star is smaller and cooler.

Other facts: HD 209458b lies 153 light years from Earth in the constellation Pegasus. TrES-1 is 489 light years away in the constellation Lyra. And while yesterday’s entry said that both HD 209458b and TrES-1 orbit stars very much like our sun, this is true only of the former; TrES-1’s star is smaller and cooler.

Image: Frame from a video simulation shows in a simplified schematic how the brightness of a star/planet system varies as the planet is eclipsed by the star. The false colors represent infrared images. Credit: NASA/JPL/Caltech-R. Hurt.

The paper on TrES-1 by David Charbonneau et al. is in press at The Astrophysical Journal, with publication slated for the June 20 issue. A preprint of the paper, “Detection of Thermal Emission from an Extrasolar Planet,” is available at the ArXiv site.

Also intriguing on the exoplanet front is planet-hunter Geoff Marcy’s intention to issue a catalog that will cover all exoplanets found to date. Marcy’s own team has thus far found almost 100 planets, and he is now turning to The Planetary Society in search of donations for the catalog.

Why is a catalog necessary? Here’s what The Planetary Society has to say in a recent release:

…most of the data is not available to the scientific community, or to the public at large. Of course, preliminary information about each world was published as it was discovered. But scientists have continued to study them, adding mountains of data to those initial observations.

So, while a massive reservoir of fantastic information about these new worlds now exists… almost no one can tap into it because the new data has never been properly processed and released. There could be critical discoveries buried in those mounds of data that have never seen the light of day.

Centauri Dreams agrees that such an updatable resource would be of scientific importance as well as providing broad educational options for students and teachers.

Subaru Measures the Spin-Orbit Alignment of a Faint Transiting

Extrasolar Planetary System

FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT:

Principal Investigator

Dr. Norio Narita, University of Tokyo

narita@utap.phys.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp, +81-3-5841-4177 (JAPAN, GMT+9 hours)

Public Information and Outreach

Dr. Tetsuharu Fuse, Subaru Telescope

tetsu@subaru.naoj.org, +1-808-934-5922 (USA, GMT-10 hours)

IMAGES AND TEXT will become available at:

http://subarutelescope.org/

PRESS PREVIEW PAGES are available now at:

http://www.naoj.org/PRESS_folder/2007/08/23/index.html

User: Press Password:23Aug2007

Subaru Measures the Spin-Orbit Alignment of a Faint Transiting

Extrasolar Planetary System

A joint Japanese/U.S. collaboration has used the Subaru Telescope’s

High Dispersion Spectrograph (HDS) to observe the transiting

extrasolar planetary system TrES-1. The observation, which allowed

the team to measure the angle between the parent star’s spin axis

and the planet’s orbital axis, is only the third time such a

spin-orbit alignment has been measured. In addition, TrES-1 is the

faintest target ever used for such a determination.

TrES-1 has a visual magnitude of about 12, which is only about 2% as

bright as the previous targets) used for such a measurement. The

team’s work has conclusively demonstrated that spin-orbit alignments

can be measured by studying the radial velocity anomaly introduced

during a transit (the so-called Rossiter-McLaughlin effect).

According to team leader Norio Narita, a graduate student at the

University of Tokyo (Japan Society for Promotion of Science Fellow,

DC2), this is important because most of the newly discovered

transiting planets from ongoing transit surveys have relatively faint

host stars. “By combining future observations of the

Rossiter-McLaughlin effect in other transiting systems,” said Narita.

“We will be able to determine the distribution of the spin-orbit

alignment angles for exoplanetary systems. Moreover, further

observations would have the potential to discover large spin-orbit

misalignments, if any, which would inspire numerous theoretical

investigations.”

More than 200 extrasolar planets have been discovered so far. The

discovery and characterization process has revealed a diversity of

planetary systems, and a variety of theoretical models have been

proposed to explain the complex process of planet formation. The

alignment of the stellar spin axis and the planetary orbital axis

(Figure 1) is a promising diagnostic for using observational data to

characterize planet formation mechanisms. For example, models

considering giant planet scattering (outward through the

protoplanetary disk) often predict tilts different from the original

orbital axis. It follows that such planets would usually have

significant misalignments. However, planets which form and migrate

inward through their birth disks would generally have negligible

misalignments.

In transiting extrasolar planetary systems (Note 1) (those where

planets cross in front of and behind their stars from our point of

view), one can measure the spin-orbit alignments by exploiting the

Rossiter-McLaughlin effect (Figure 2). Prior to the Subaru team’s

work, measurements of two bright transiting systems were conducted by

an international team using the Keck Telescope, led by Prof. Joshua

Winn (MIT), and a co-investigator on the Subaru team. The TrEs-1

observing collaboration, which also used the MAGNUM 2-meter telescope

at Haleakala, Hawai’i, (Figure 3) in addition to the Subaru High

Dispersion Spectrograph, succeeded in detecting the

Rossiter-McLaughlin effect (Figure 4) for the first time for that

target and constrained the alignment angle to 30 degrees with an

error of plus or minus 21 degrees and clearly indicating the prograde

orbital motion of TrES-1b.

This result will be published in the August 25, 2007 issue of

Publications of Astronomical Society of Japan.

References

Measurement of the Rossiter–McLaughlin Effect

in the Transiting Exoplanetary System TrES-1

Narita, N., Enya, K., Sato, B., Ohta, Y., Winn, J. N., Suto, Y., Taruya, A.,

Turner, E. L., Aoki, W., Tamura, M., Yamada, T., Yoshii, Y. 2007,

Publ. Astron. Soc. Japan, vol 59, No. 4, 763-770

Extrasolar planetary systems in which a planet’s orbit passes in front of

its host star (namely, causing an eclipse) are called transiting extrasolar

planetary systems.

TrES-1 is a main sequence K0 star and its planet TrES-1b was discovered by

the transit survey in 2004. TrES-1b is a gaseous giant orbiting the host star

with a period of about three days (one of the so called “hot Jupiter” class of

extrasolar planets).

An illustration of the concept of the spin-orbit alignment (indicated by

lambda) in an exoplanetary system.

The Rossiter-McLaughlin effect is defined as the radial velocity anomaly

during a transit from the known Keplerian orbit caused by the partial

occultation of the rotating stellar disk. For example, if a planet occults

part of the blue-shifted (approaching) half of the stellar disk, then the

radial velocity of the star will appear to be slightly red-shifted, and

vice-versa. The radial velocity anomaly depends on the trajectory of the

planet across the disk of the host star, and in particular on the spin-orbit

alignment of the system. Thus by monitoring the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect

one can measure the spin-orbit alignment.

A photometric light curve of TrES-1 from the MAGNUM observation (top),

and radial velocities obtained with the Subaru/HDS (bottom). The light curve

shows that the observations were conducted around a transit of TrES-1b.

Orbital plots of TrES-1 radial velocities and the best-fitting models

including the Kepler motion and the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect.

Left panel: A radial velocity plot for the whole orbital phase.

Right panel: A close-up of the radial velocity plot around the transit phase.

The waveform around the central transit time (phase = 0) is caused by the

Rossiter-McLaughlin effect.

Bottom panels: Residuals from the best-fit curve.