Sometimes all it takes to spawn a new idea is a tiny smudge in a telescopic image. What counts, of course, is just what that smudge implies. In the case of the object called ‘Oumuamua, the implication was interstellar, for whatever it was, this smudge was clearly on a...

Search Results:

Is Planet Nine Alone in the Outer System?

It was Robert Browning who said “Ah, but a man's reach should exceed his grasp, or what's a heaven for?” A rousing thought, but we don’t always know where we should reach. In terms of space exploration, a distant but feasible target is the solar gravitational lens...

Deep Space Implications for CubeSats

The Hera mission has been dwarfed in press coverage by the recent SpaceX Starship booster retrieval and the launch of Europa Clipper, both successful and significant. But let’s not ignore Hera. Its game plan is to check on the asteroid Dimorphos, which became the...

Space Exploration and the Transformation of Time

Every now and then I run into a paper that opens up an entirely new perspective on basic aspects of space exploration. When I say ‘new’ I mean new to me, as in the case of today’s paper, the relevant work has been ongoing ever since we began lofting payloads into...

SETI and Gravitational Lensing

Radio and optical SETI look for evidence of extraterrestrial civilizations even though we have no evidence that such exist. The search is eminently worthwhile and opens up the ancillary question: How would a transmitting civilization produce a signal strong enough for...

Solar Gravity Lens Mission: Refinements and Clarifications

Having just discussed whether humans – as opposed to their machines – will one day make interstellar journeys, it’s a good time to ask where we could get today with near-term technologies. In other words, assuming reasonable progress in the next few decades, what...

Interstellar Precursor? The Statite Solution

What an interesting object Methone is. Discovered by the Cassini imaging team in 2004 along with the nearby Pallene, this moon of Saturn is a scant 1.6 kilometers in radius, orbiting between Mimas and Enceladus. In fact, Methone, Pallene and another moon called Anthe...

To Build an Interstellar Radio Bridge

I sometimes imagine Claudio Maccone having a particularly vivid dream, a bright star surrounded by a ring of fire that all but grazes its surface. And from this ring an image begins to form behind him, kilometers wide, dwarfing him and carrying in its pixels the view...

Game Changer: Exploring the New Paradigm for Deep Space

The game changer for space exploration in coming decades will be self-assembly, enabling the growth of a new and invigorating paradigm in which multiple smallsat sailcraft launched as ‘rideshare’ payloads augment huge ‘flagship’ missions. Self-assembly allows...

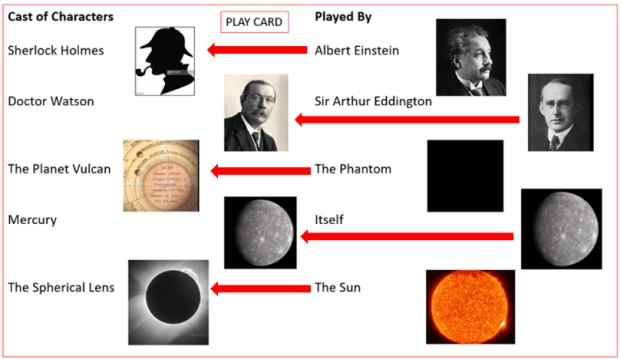

Part II: Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Spherical Lens: Reflections on a Gravity Lens Telescope

Aerospace engineer Wes Kelly continues his investigations into gravitational lensing with a deep dive into what it will take to use the phenomenon to construct a close-up image of an exoplanet. For continuity, he leads off with the last few paragraphs of Part I, which...