Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

A Strong Case for TRAPPIST-1 Planets

TRAPPIST continues to be my favorite astrophysical acronym. Standing for Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope, the acronym flags a robotic instrument at the La Silla Observatory in Chile that is operated by the the Institut d’Astrophysique et Géophysique (University of Liège, Belgium) in cooperation with the Geneva Observatory. The name is a nod to the branch of the Cistercian order of monks called Trappists, whose beer is world-renowned and closely associated with Belgium itself (although also brewed in the Netherlands and a few other countries). A jolly telescope indeed.

You’ll recall TRAPPIST-1 as the far more approachable term for the red dwarf star 2MASS J23062928-0502285, a bit over 39 light years away in the direction of the constellation Aquarius. A 2016 paper in Nature announced three rocky planets orbiting the star, one of which could conceivably be in its habitable zone, where liquid water can exist on the surface. Now we have a helpful follow-up from the 8-meter Gemini South telescope in Chile. A team led by Steve Howell (NASA Ames) has been able to rule out any close stellar companion.

That’s good news for planet hunters because what we have been looking at are fluctuations in the light of this small star (TRAPPIST-1 is only about 8 percent of the Sun’s mass), making the assumption that these were caused by the three planets mentioned above. Howell used the Differential Speckle Survey Instrument (DSSI) at Gemini South to demonstrate that there was no hitherto undiscovered small star complicating an already complicated planetary detection.

“By finding no additional stellar companions in the star’s vicinity we confirm that a family of smallish planets orbit this star,” says Howell. “Using Gemini we can see closer to this star than the orbit of Mercury to our Sun. Gemini with DSSI is unique in being able to do this, bar none.”

Speckle imaging, which is what the DSSI instrument Howell used in this work does, works by taking numerous extremely short exposures, allowing astronomers to combine the images and eliminate distortion caused by the Earth’s atmosphere. We wind up with high-resolution images that duplicate what the same telescope would produce if it were in space.

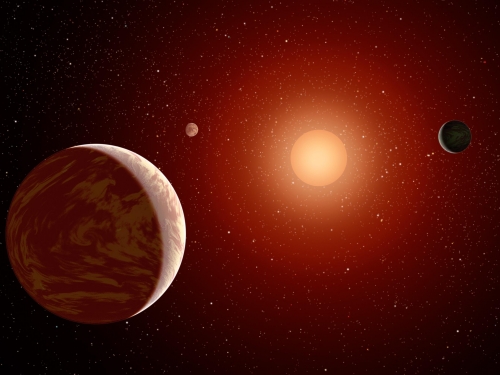

Image: Artist’s concept of what the view might be like from inside the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanetary system showing three Earth-sized planets in orbit around the low-mass star. This planetary system is located only 40 light years away. Gemini South telescope imaging, the highest resolution images ever taken of the star, revealed no additional stellar companions, providing strong evidence that three small, probably rocky planets orbit this star. Credit: Robert Hurt/JPL/Caltech.

Ongoing work may detect further planets in this system, but for now, what we have are the original three. The inner worlds are in orbits of 1.5 and 2.4 days respectively, both far too hot for liquid water on the surface; in fact, these two would receive four and two times the radiation the Earth does from the Sun respectively. The third planet’s orbital period has proven difficult to constrain, so that all we can say is that it is between 4 and 73 days, though this Gemini Observatory news release pegs the most likely period at 18 days, which would evidently be in the habitable zone. Confirming that would add to the sizzle of the recent Proxima Centauri b discovery.

Thus we continue to learn about TRAPPIST-1, a promising candidate for still more detailed work in coming years. M-dwarfs are small enough that planets in their habitable zone have short orbital periods. That means frequent transits, giving astronomers the chance to analyze their planets’ atmospheres by studying starlight as it is filtered through them. The odds on the Proxima Centauri planet transiting are slight (we’ll soon know more), but in TRAPPIST-1 we have the potential for follow-up with space-borne instruments and the coming generation of extremely large telescopes (ELTs) on the ground, to learn what kind of atmospheres such planets have, and whether we may eventually find biosignatures within them.

The Howell paper is “Speckle Imaging Excludes Low-Mass Companions Orbiting the Exoplanet Host Star TRAPPIST-1,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 829, No. 1 (abstract). The original work on TRAPPIST-1 is Gillon et al., “Temperate Earth-sized Planets Transiting a Nearby Ultracool Dwarf Star,” published online in Nature 2 May 2016 (abstract).

On Planets in Binary Systems

Alpha Centauri A and B, the two primary stars of the Alpha Centauri threesome, orbit a common center of gravity, with an average separation of 23.7 AU. But bear in mind that this average covers wider ground. The separation can close to about 11 AU or widen to as far as 36 AU. I bring these distances up because it’s an open question whether there are planets around either of these stars. The possibility exists that we might find planets around both, and of course we already know of that interesting planet circling nearby Proxima Centauri.

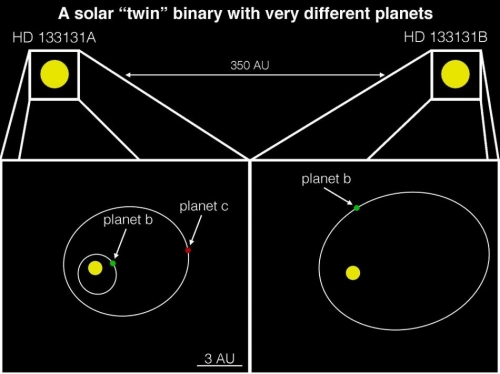

Do we have examples of close binaries in which we find a planet around each star? Until late August, the closest known binary system with planets orbiting both individual stars showed a separation of 1000 AU. But now we have the twin stars HD 133131A and HD 133131B. Around the former we have two planets, one whose minimum mass is about 1.5 times Jupiter’s mass, the other with a minimum of about half Jupiter’s mass. The second star hosts a planet of about 2.5 Jupiter’s mass. These stars aren’t nearly as close as the Alpha Centauri stars, but their separation is still small, about 360 AU.

This is an interesting find, pulled off by a team of Carnegie scientists and scheduled to appear in The Astronomical Journal. The work draws on data from the Planet Finder Spectrograph mounted on instruments at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile. The Carnegie work has focused on large planets in elliptical or long-duration orbits, in an attempt to learn whether Jupiter-sized planets are as comparatively rare as current statistics suggest.

“We are trying to figure out if giant planets like Jupiter often have long and, or eccentric orbits,” said Johanna Teske (Carnegie Observatories). “If this is the case, it would be an important clue to figuring out the process by which our Solar System formed, and might help us understand where habitable planets are likely to be found.”

Image: An illustration of this highly unusual system, which features the smallest-separation binary stars that both host planets ever discovered. Only six other metal-poor binary star systems with exoplanets have ever been found. Credit: Timothy Rodigas.

We’re pushing radial velocity methods hard in this work. In fact, the authors note that we have only a dozen or so planets detected with this technique that have periods of 3600 days or more. The outer planets around HD 133131A and B thus become interesting data points as we try to analyze how frequently giant planets in eccentric orbits and long orbital periods appear.

As to the stars themselves, both are believed to be metal-poor and probably in the range of 9.5 billion years old. And that raises questions in itself, as the paper notes, because we’re used to thinking of giant planets forming in a more metal-rich environment. In the segment below, Tc stands for condensation temperatures:

…we find a small but significant depletion of high Tc (> 1000 K) elements in HD 133131A versus B, and explore how this could be related to differences in planet formation, interactions between the planets and the two stars, and/or the composition of the planets orbiting the two stars. This system is the smallest separation “twin” binary system for which such a detailed abundance analysis has been conducted. Overall, HD 133131A and B are especially noteworthy because they are metal-poor but are orbited by multiple giant planets, contradictory to the predicted giant planet-metallicity correlation. The planets detected here will be important benchmarks in studies of host star metallicity, binarity of host stars, and long period giant planet formation.

Understanding the behavior of gas giants will eventually help us piece together our own Solar System’s formation, because we already know that Jupiter and Saturn helped to shape the asteroid belt in the system’s early days, and also were factors in the delivery of volatile materials to the inner rocky worlds. Whether or not our Solar System’s configuration is rare depends largely on the occurrence of giant planets in long-period orbits. Yet recent studies suggest that true Jupiter analogs in similar orbits occur around only one to four percent of host stars.

What we are now learning is that even if Jupiter analogs are rare, there are numerous possibilities among giant planets on highly eccentric orbits, which could have major consequences on the formation of inner rocky worlds. We now try to learn whether long-period gas giants are as unusual as they seem, and whether they are more frequently eccentric, all factors that play into key questions of planetary habitability as infant systems emerge.

The paper is Teske et al., “The Magellan PFS Planet Search Program: Radial Velocity and Stellar Abundance Analyses of the 360 AU, Metal-Poor Binary “Twins” HD 133131A & B,” accepted at The Astronomical Journal (preprint).

Star Trek Plus Fifty

The founder of the Tau Zero Foundation takes a look at the promise of Star Trek, and asks where we stand with regard to the many technologies depicted in the series. My own first memory of Star Trek is seeing a first year episode and realizing only a few days later that it had been one of the few times a TV science fiction show never mentioned the Earth. That was an expansive and refreshing perspective-changer from the normal fare of 1966, though back then I would never have dreamed how much traction the show would gain over time. But with the series now a cultural icon, how about Starfleet’s tech? Will any of it actually be achieved?

by Marc Millis

This week marks the 50th anniversary of Star Trek‘s debut. In just 3 seasons, the series started a cultural ripple effect that’s still going. The starship Enterprise became an icon for a better future – predicting profound technical abilities, matched with a rewardingly responsible society, and countless wonders left to explore. Many engineers and scientists trace their career inspirations to that show. The effect spread worldwide and has been described as a yearning for “a deep and eternal need for something to believe in: something vast and powerful, yet rational and contemporary. Something that makes sense.” [1]

Now, half a century later, how are we doing toward realizing the fantastic futures of Trek? Are we making progress on faster-than-light flight (FTL), control over inertial and gravitational forces, extreme energy prowess, and the societal discipline to harness that much power responsibly?

I directed NASA’s “Breakthrough Propulsion Physics” project – NASA’s first documented inquiry into the prospects of Star-Trek-like breakthroughs – controlling gravity for propulsion and achieving faster-than-light flight. That project was funded from 1995-2002, and continued unfunded through around 2008. With the help of networks beyond NASA via the Tau Zero foundation, the results of the NASA work plus many others were compiled into Frontiers of Propulsion Science, (2009). There has been some more progress from multiple places since then, but by and large that compilation is still a decent starting point into the details.

FTL

Let’s start with the most obvious and glamorous – faster than light flight. The first scientific paper about FTL wormholes appeared in 1988 [2], followed 7 years later with an extensive scholarly book on the topic [3]. Alcubierre’s “warp drive” paper appeared in 1994 [4] and a recent progress report on FTL approaches is available here [5].

In short, FTL is now a theoretical possibility, anchored in Einstein’s general relativity, even though daunting challenges remain. Instead of violating the lightspeed limit through spacetime, these theories are about manipulating spacetime itself – which is an entirely different situation. A significant next-step challenge is to find a way to create bare negative energy – and a lot of it. While negative energy can be created now (such as within Casimir cavities), the catch is that it is still contained inside of a greater amount of normal positive mass-energy. The first experimental demonstration of bare negative energy would be a pivotal moment.

A few other lessons followed: Wormholes are likely to be a more energy-efficient way of achieving FTL than warp drives. The previously touted time-travel paradoxes that seemed to prevent FTL have been found to be non-issues (You cannot use FTL flight to go back in time and kill your grandfather before your father is born). And the last lesson is that better theoretical tools are needed. Many of the FTL investigations have been limited to 1-dimensional analysis rather than full-up 3D spacetime. The theory for FTL flight is there, but still in its infancy.

For fun, I calculated how fast we would need to fly to get as much action as Captain Kirk. In their 5-year mission (of 3 seasons) they seemed to encounter a new civilization almost every episode – 79 episodes. Combining that with a provisional estimate of 1900 light-years between civilizations [6], yields a required speed of 30,000 times lightspeed. That’s about 300 million times faster than today’s spacecraft.

Recall that, on interstellar scales, lightspeed is slow. At lightspeed, our closest neighboring star, Proxima Centauri, is over 4.2 years away. Our next nearest 10 stars are within about 10 light years away. To reach Proxima Centauri within a person’s career span (say 42 years), we have to get our spacecraft up to 10% lightspeed. That’s over 1000 times faster than we’ve done before.

Transporters

To reduce production budgets, Trek included “transporters” to move people from one point to another with just a scene change – plus noises and lighting effects. The premise is that the people would be dematerialized into some sort of energy beam that could then rematerialize somewhere else. Despite the similar nomenclature with “quantum teleportation” (a real thing) Trek transporters are an entirely different animal. The closest thing in the scientific literature to creating a transporter effect is a wormhole – discussed previously.

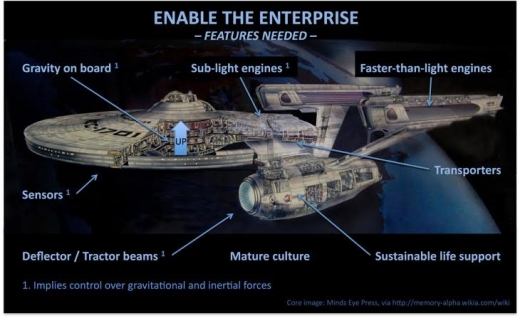

Control over Gravitational and Inertial forces

Many of the key features of the starship Enterprise require the ability to manipulate gravitational and inertial forces. The most obvious feature is internal gravitation for its crew – which conveniently matches studio conditions. Think about it – in the middle of space, far from any gravitating body, there is no “down” to fall toward. Things just float.

The ability to induce a gravitational field inside of a spacecraft would be a huge breakthrough with all sorts of spin-offs. If we could induce a gravitational field inside the spacecraft, then why not outside as well – as a form of propulsion? This leads next to concepts like “tractor beams” and “deflectors,” to push objects out of the way of the screaming-through Enterprise. And… if you can push and pull distant objects, it’s likely that you can also sense them in a way that defies contemporary familiarity, such as identifying distant objects by their mass density (convenient for gold prospecting).

While the need for FTL is glaringly obvious, the implications of these mass-based breakthroughs are harder to grasp. Consider this analogy. Long ago, electric charges and magnets were known to exist but not understood. Things got interesting when we learned that electricity can create magnetic fields, and magnetic fields can generate electricity. Thereafter motors, generators, lighting, and… even the computer screen that you are reading this on… were invented.

Similarly, we know that gravitation and electromagnetism exist. Newton got as far as deciphering the behavior of gravity and inertia and then Einstein extended those to include electromagnetism, relativistic speeds, and intense gravitation. But we do not yet understand how that works. If we ever figure out how to use our prowess in electromagnetism to affect changes in gravitation or inertia, then all those Trek-ish visions might be realized, including zero-gravity recreational hotel rooms. The first experimental evidence of such abilities would be a turning point for humanity.

Physics in general has been seeking such knowledge and making progress since its very beginning. Over recent decades other phenomena have been discovered that challenge our existing theoretical models. There is plenty of room for new empirical discoveries and theoretical ‘ah-ha’ moments. When examined in the context of breakthrough propulsion, different lines of inquiry are added. For example, the search for “space drive” effects has revealed the importance of understanding the origins of inertial frames [7].

Extreme Energy Prowess

To achieve interstellar flight, even in the conventional sense, requires incredible amounts of energy. To bump our spacecraft speeds up to 10% lightspeed (1000 times faster than now), we need at least 1-million times more energy. While these sorts of numbers are conceivable within future decades, there are secondary issues which often get overlooked in both the fiction and even in some engineering studies. One example is how to get rid of the waste heat. When converting one form of energy to another, there are inefficiency losses. For something as small as a car engine or air-conditioner, the excess heat is easy to vent to the atmosphere. But when the energy levels get extreme and if they are used in space where it is harder to radiate that energy, then even a 1% inefficiency can lead to enormous challenges. These are not show-stoppers, but details that are a part of the big picture.

When considering the FTL theories, the required energy levels become astronomical. An old example (from Matt Visser) is that to create a 1-meter diameter wormhole, one would need to get as much rest-mass-energy as the whole planet Jupiter, convert it in the form of bare negative energy, and then make it small enough to create that 1-meter opening. Subsequent analyses have brought those estimates much lower, but we are still talking mind-boggling feats of energy prowess. Any new theory or experiment that shows how to warp spacetime with achievable energies would be a pivotal development.

A significant secondary issue is how to use that energy safely. The energy levels of interstellar flight are so great that, if misused, could wipe out all life on Earth. This leads to another key feature of the Star Trek visions – a mature society that wields its power responsibly.

Societal Maturity

Although Star Trek was thought-provoking from the technological point of view, it was also very comforting from a sociological point of view. The crew of the Enterprise behaved in an honorable and respectful manner to each other and to other cultures, despite differences in background, race, sex, or character. They did not abuse their power. Even though they worked toward common goals, each individual had their special niche. Several episodes featured the crew of the Enterprise coming to the rescue of some civilization that gone astray because of their lack of sensible treatment toward each other. Most often those wayward societies would learn their Trek lesson and turn the corner to a better life. If only it were that easy to get people to override their errant beliefs with facts, wisdom, and a good role model.

Of all the challenges, this one is probably the most difficult and the most needed. The survival of humanity. depends on it. To safely wield our growing powers, our society will have to mature to where we work for the common good rather than against each other. A glimmer of hope is that we have refrained from unleashing a nuclear holocaust for over a half century, despite precarious international bickering from time to time. I’ve also read articles that, proportionally, we are killing each other less. Compared to human history, however, a half-century is a tiny moment. As the decades tick by and our energy prowess grows, will all of us wield our powers responsibly? Will we learn to live in a manner where our disagreements do not become life-threatening?

The difficulty of creating these societal improvements is that the tools we have are the same thing that we are trying to fix. To make society healthier, we need a healthy society. When we are part of the problem that we are trying to solve, there is a limit to our perspectives. It’s a bit like asking a vacuum cleaner to suck itself up.

One way to step back and see ourselves more impartially is to contemplate far future societies in the form of “world ships.” Imagine a colony of 50,000 people constrained in a finite ship headed across space for centuries. In addition to sustaining physical life support, their society will have to sustain a peaceful and meaningful culture. Such challenges are explored in the disciplines of Astrosociology and Space Anthropology. Perhaps as more rigorous data about human behavior accumulates, along with methods for complex data analysis, we will eventually figure out how to design a society that accommodates the full realities of human behavior in a manner where individuals can live meaningful lives within a lasting peaceful culture.

Closing Thought – Reflections on Proxima b

It’s been said that having a moon so close to Earth helped create the space program. The science fiction for that step began with Jules Verne in 1865, followed by the mathematical foundations from Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in 1903, and culminating in the Apollo moon landing in 1969. Roughly a half century from fiction to science, and another half century from science into substance.

Now we have an potentially habitable planet as close as it could possibly be. Our nearest neighboring star, Proxima Centauri, has a planet a little bit bigger than Earth which might have liquid water. It’s 4.2 light years away, has a mass 30% more than Earth, and is in the habitable zone of its red dwarf star. Its star is dimmer, cooler, and tiny compared to our Sun (14% the size, 12% the mass), which means that its habitable zone is only 5% the distance between our Sun and Earth. Accordingly, a year on the new-found planet is only 12 Earth days. The science is here.

For those of us who have been contemplating interstellar flight longer than we’ve known better (Tau Zero is a decade old this year), it couldn’t get any better than this – unless we later learn that the planet does indeed have an atmosphere, proof of liquid water, and the right spectral clues for life. This distance makes it within reach of conceivable probes. Just earlier this year, billionaire Yuri Milner committed $100 million for research into one approach to interstellar flight, laser pushed light sails, dubbed Breakthrough Starshot. That particular idea is decades old, with the first detailed analysis done by Robert Forward in the 1980’s. Starshot hopes to nudge the idea from concept to technological proofs of concept.

Centauri b beckons. Will this be the catalyst to nudge interstellar flight toward reality? Consider that the notion of space sails dates back to at least 1929 (and can actually be traced in some form all the way back to the works of Kepler). Those foundations were converted into science by the late 1980’s, and Starshot is trying to mature the science into technology now. If the pattern of the Moon shot repeats, we’ll have probes on their way to Proxima by the 2040s. And consider this. The science fiction for faster than light flight dates back to John W. Campbell in 1931, and the first science articles were in 1988 and 1994. If the pattern repeats there too, we might have warp drives reaching the planet “Proxima b” before Starshot even gets there.

Ad astra incrementis

References

[1] Greenwald, J. (1988). Future Perfect: How Star Trek Conquered Planet Earth. (Viking).

[2] Morris, M. S., & Thorne, K. S. (1988). “Wormholes in spacetime and their use for interstellar travel: A tool for teaching general relativity.” Am. J. Phys, 56(5), 395-412.

[3] Visser, M. (1996). Lorentzian wormholes. From Einstein to Hawking. (AIP Press), 1.

[4] Alcubierre, M. (1994). “The warp drive: hyper-fast travel within general relativity.” Classical and Quantum Gravity, 11(5), L73.

[5] Davis, E. W. (2013). Faster-Than-Light Space Warps, Status and Next Steps. In 48th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit (p. 3860).

[6] Maccone, C. (2011). “SETI and SEH (statistical equation for habitables),” Acta Astronautica, 68(1), 63-75.

[7] Millis, M. G. (2012). “Space Drive Physics: Introduction and Next Steps.” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, 65, 264-277.

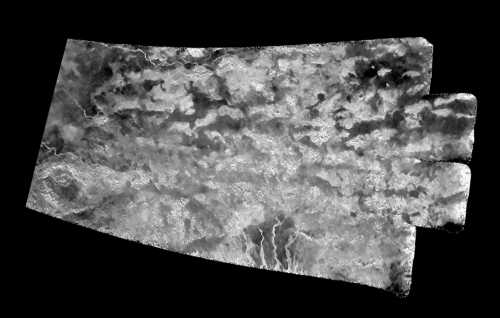

Last Images of Titan’s Far South

Have a look at an image Cassini acquired on July 25 of this year during its T-121 flyby of Titan. Here we’re dealing with a synthetic-aperture radar image, but one that has been cleaned up with a ‘denoising’ algorithm that produces clearer views. Because of its proximity to the Xanadu region, the mountainous terrain shown here has been named the ‘Xanadu annex’ by Cassini controllers. Both features block the formation of sand dunes, which are elsewhere ubiquitous around Titan’s equator. As on Earth, Titan’s dunes flow around the obstacles they meet.

These are the first Cassini images of the Xanadu annex, which is now revealed to be made up of the same mountainous terrain seen in Xanadu itself. Referring to the first detection of Xanadu, which occurred in 1994 through Hubble Space Telescope observations, JPL’s Mike Janssen, a member of the Cassini radar team, calls the annex ‘an interesting puzzle,’ adding:

“This ‘annex’ looks quite similar to Xanadu using our radar, but there seems to be something different about the surface there that masks this similarity when observing at other wavelengths, as with Hubble.”

Image: The area nicknamed the “Xanadu annex” by members of the Cassini radar team, earlier in the mission. This area had not been imaged by Cassini’s radar until now, but measurements of its brightness temperature from Cassini’s microwave radiometer were quite similar to that of the large region on Titan named Xanadu. Cassini’s radiometer is essentially a very sensitive thermometer, and brightness temperature is a measure of the intensity of microwave radiation received from a feature by the instrument. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/Universite Paris-Diderot.

While mountainous terrain is found elsewhere on Titan, the Xanadu region is large and somewhat reminiscent of a famous area in the north-central US, according to Rosaly Lopes (JPL), a member of the Cassini radar team. Says Lopes:

“These mountainous areas appear to be the oldest terrains on Titan, probably remnants of the icy crust before it was covered by organic sediments from the atmosphere. Hiking in these rugged landscapes would likely be similar to hiking in the Badlands of South Dakota.”

Cassini closed to within a bit less than a thousand kilometers of Titan on the T-121 pass, its radar looking through the moon’s global haze to produce details of the surface. JPL has produced a video that shows long, linear dunes that scientists believe are made up of grains derived from hydrocarbons settling out of Titan’s atmosphere.

We have four Cassini flybys of Titan left before mission’s end, and this one marks the last time the spacecraft’s radar will image the far southern latitudes. The remaining flybys are to focus on the far north, an area famous for its lakes and seas. Maybe it’s just the gradual approach of autumn here in North America, but all of these late flybys have a kind of elegiac quality for me. After all, it will be next spring that the spacecraft begins the series of orbits that take it between Saturn and its rings, to be followed by entry into Saturn’s atmosphere on September 15, 2017.

Cassini’s fiery end is a move designed to prevent any biological contamination of Titan, Enceladus and any other conceivable habitat, but it’s going to be painful to watch given the rich data and imagery the craft has given us since orbital insertion at Saturn in July of 2004.

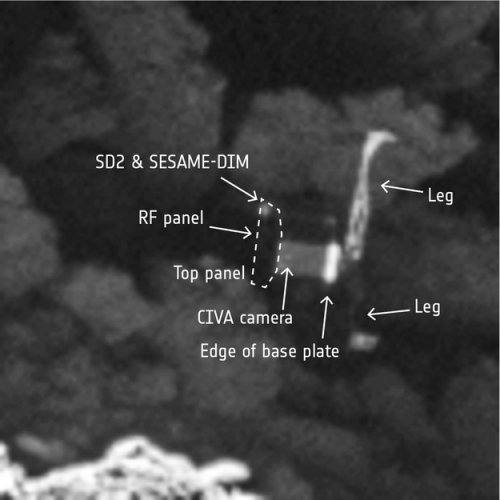

Philae Lander Found as Rosetta Nears End

We’re only a month away from further excitement from Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. As the mission approaches its final days, the Rosetta orbiter will conclude its activities with a controlled descent to the region called Ma’at, an area of open pits on the comet’s surface that may reveal information about its interior structure. The descent, which will occur on September 30, comes after the months of intense scrutiny that led to the location of the Philae lander.

We did get data from Philae, but as you know, shortly after its initial touchdown at Agilkia, the lander bounced and continued to drift over the surface for another two hours. Its final location, on the comet’s smaller lobe, was subsequently named Abydos. Philae’s hibernation, after only three days, was the result of battery exhaustion, but the lander was able to communicate again with Rosetta in June and July of 2015 as the comet moved toward perihelion in August.

Even then, controllers didn’t know Philae’s precise location, although they had pinned it down to an area tens of meters across in which several candidate objects appeared in the low-resolution images that Rosetta was able to deliver at that time. Now we have new imagery taken on September 2 by the OSIRIS narrow-angle camera as the orbiter closed to within 2.7 kilometers of the surface. Here the lander’s main body and two of its legs are clearly visible.

Image: A number of Philae’s features can be made out in this image taken by Rosetta’s OSIRIS narrow-angle camera image on 2 September 2016. The images were taken from a distance of 2.7 km, and have a scale of about 5 cm/pixel. Philae’s 1 m wide body and two of its three legs can be seen extended from the body. Several of the lander’s instruments are also identified, including one of the CIVA panoramic imaging cameras, the SD2 drill and SESAME-DIM (Surface Electric Sounding and Acoustic Monitoring Experiment Dust Impact Monitor).

Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA.

Matt Taylor (ESA), a project scientist for Rosetta, notes the significance for mission data:

“This wonderful news means that we now have the missing ‘ground-truth’ information needed to put Philae’s three days of science into proper context, now that we know where that ground actually is!”

ESA’s Laurence O’Rourke, who has been coordinating the search efforts over the last months at ESA with the OSIRIS and SONC/CNES (Science Operations and Navigation Center at the French National Centre for Space Studies) teams, adds:

“After months of work, with the focus and the evidence pointing more and more to this lander candidate, I’m very excited and thrilled that we finally have this all-important picture of Philae sitting in Abydos.”

So the lander search comes to an end even as we look toward still more detailed images when Rosetta nears the surface. I also want to mention this footage of an outburst on 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko which may have been triggered by a landslide. The outburst occurred on February 19, although the imagery was not published until the 25th of August. Rosetta’s nine instruments were monitoring the comet from about 35 kilometers away when the outburst occurred, a fortuitous occurrence since outbursts have proven to be highly unpredictable. As this ESA news release explains, we have retrieved a harvest of data.

Image: Comet outburst. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA.

ESA scientists believe the outburst came from a steep slope on the comet’s largest lobe, in a region called Atum. What’s interesting here is that this region had just emerged from shadow when the outburst occurred, leading to the possibility that temperature changes created stress in the surface material that triggered a landslide. This, in turn, would have exposed fresh water ice to direct illumination from the Sun, causing sublimation that pulled dust along with it.

Eberhard Grün (Max-Planck-Institute for Nuclear Physics) is lead author of a new paper on the outburst:

“Combining the evidence from the OSIRIS images with the long duration of the GIADA dust impact phase leads us to believe that the dust cone was very broad. As a result, we think the outburst must have been triggered by a landslide at the surface, rather than a more focused jet bringing fresh material up from within the interior, for example.”

We’ll keep a close eye on Rosetta as the mission nears its end, hoping for impressive final imagery. The paper is Grün et al., “The 19 Feb. 2016 Outburst of Comet 67P/CG: An ESA Rosetta Multi-Instrument Study,” published online by Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 25 August 2016 (abstract). The ESA news release on the Philae discovery is here.

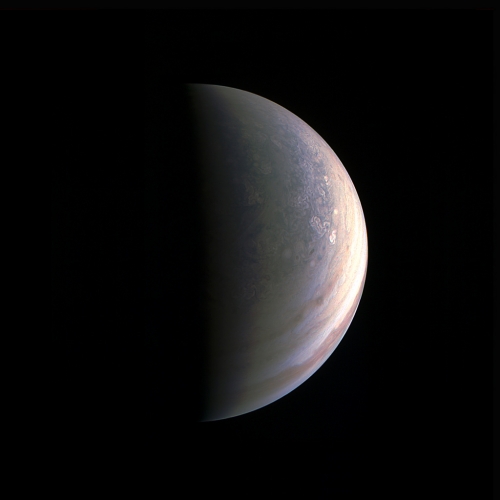

Juno’s First Look at Jupiter’s Poles

Since I’ve just finished reading Stephen Baxter and Alastair Reynolds’ The Medusa Chronicles, a great deal of the action of which takes place beneath the upper clouds of Jupiter, I’m finding the Juno mission more than a little fascinating. The novel shows us a Jupiter that is the habitat of a variety of dirigible-like lifeforms, along with the predators that make their life difficult, and a mysterious world far beneath that I won’t spoil for you by describing.

Juno is delving into mysteries of its own. The spacecraft’s first images of Jupiter’s north pole, taken on August 27, mark the first of 36 close passes that will define the mission. As is so often the case with first-time planetary discovery, we are seeing things we didn’t expect. Scott Bolton (SwRI) is Juno principal investigator:

“First glimpse of Jupiter’s north pole, and it looks like nothing we have seen or imagined before. It’s bluer in color up there than other parts of the planet, and there are a lot of storms. There is no sign of the latitudinal bands or zone and belts that we are used to — this image is hardly recognizable as Jupiter. We’re seeing signs that the clouds have shadows, possibly indicating that the clouds are at a higher altitude than other features.”

Image: As NASA’s Juno spacecraft closed in on Jupiter for its Aug. 27, 2016 pass, its view grew sharper and fine details in the north polar region became increasingly visible. The JunoCam instrument obtained this view on August 27, about two hours before closest approach, when the spacecraft was 195,000 kilometers away from the giant planet (i.e., from Jupiter’s center). Unlike the equatorial region’s familiar structure of belts and zones, the poles are mottled with rotating storms of various sizes, similar to giant versions of terrestrial hurricanes. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS.

And we also learn that, unlike Saturn, Jupiter has no hexagon at its north pole. If it had been there, Juno would surely have found it, with all eight of its science instruments collecting data during the flyby, including the Italian Space Agency’s Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM), which acquired infrared imagery at both north and south polar regions. We learn from the first-ever such imagery of these regions that both poles show warm and hot spots. “JIRAM,” says instrument co-investigator Alberto Adriani (Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome), “is getting under Jupiter’s skin…”

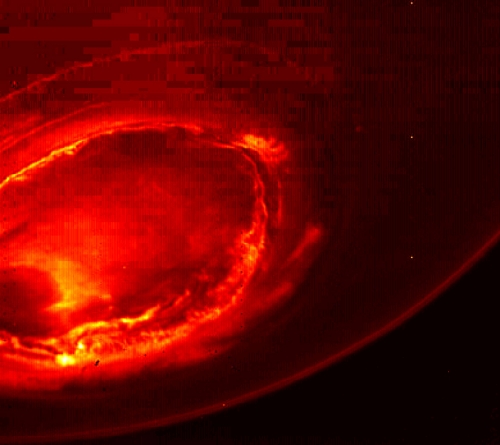

“These first infrared views of Jupiter’s north and south poles are revealing warm and hot spots that have never been seen before. And while we knew that the first ever infrared views of Jupiter’s south pole could reveal the planet’s southern aurora, we were amazed to see it for the first time. No other instruments, both from Earth or space, have been able to see the southern aurora. Now, with JIRAM, we see that it appears to be very bright and well structured. The high level of detail in the images will tell us more about the aurora’s morphology and dynamics.”

Image: This infrared image gives an unprecedented view of the southern aurora of Jupiter, as captured by NASA’s Juno spacecraft on August 27, 2016. The planet’s southern aurora can hardly be seen from Earth due to our home planet’s position in respect to Jupiter’s south pole. Juno’s unique polar orbit provides the first opportunity to observe this region of the gas-giant planet in detail. Juno’s Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) camera acquired the view at wavelengths ranging from 3.3 to 3.6 microns — the wavelengths of light emitted by excited hydrogen ions in the polar regions. The view is a mosaic of three images taken just minutes apart from each other, about four hours after the perijove pass while the spacecraft was moving away from Jupiter. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM.

Jupiter is capable of violent radio outbursts at frequencies below 40 MHz. I can remember as a boy scanning, with an old Lafayette shortwave receiver, somewhere around 20 MHz, hoping to pick up signs of this activity, which seems to correlate usefully with Io’s position in its orbit. I picked up plenty of noise at various places on the dial, but was too inexpert to know which, if any, could have been signs of Jupiter’s radio storms. Fortunately, Juno has a Radio/Plasma Wave Experiment (Waves), which was able to record the emanations from close by.

The radio activity is coming from the kind of energetic particles that create the gas giant’s aurorae. The Waves experiment should give us a lot more understanding of the phenomenon in coming months. JPL has a video on the auroral activity now available on YouTube. I’ll insert it below, but let me know if this insertion is successful. Recently I’ve heard from a small number of readers that the YouTube material doesn’t display (it seems to work for most, however). I’m still trying to figure out what the glitch is, so if you don’t see it, drop me a note in the comments

No sign of Baxter and Reynolds’ medusae, which are actually Arthur C. Clarke’s medusae, enormous living zeppelins that he described in his 1971 novella “A Meeting with Medusa” (the new novel follows the continuing story of the novella’s protagonist). But then, Juno isn’t exactly designed as an astrobiology experiment. Who knows what exotica it may pass by when it de-orbits and eventually burns up in the dense atmosphere during its 37th orbit…