Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Proxima Centauri Planet

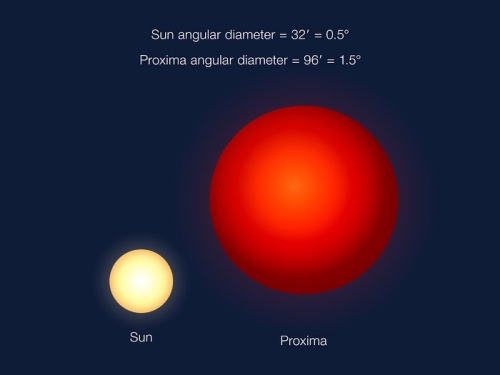

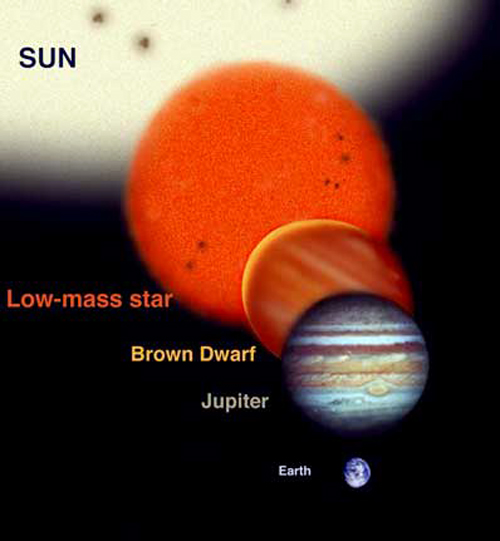

A planet in the habitable zone around Proxima Centauri? The prospect dazzles the imagination, but then, I’ve been thinking about just that kind of planet for most of my life. Proxima Centauri is, after all, the closest star to our own, about 15000 AU from the primary Alpha Centauri stars (though thought to be moving with that system). A dim red dwarf, Proxima wasn’t discovered until 1915, but it quickly seized the imagination of science fiction writers who pondered what might exist around such a star. Murray Leinster’s story “Proxima Centauri” (1935) is a clanking, thudding tale but it still evokes a bit of the magic of one of the earliest fictional interstellar voyages.

Image: This wide-field image shows the Milky Way stretching across the southern sky. The beautiful Carina Nebula (NGC 3372) is seen at the right of the image glowing in red. It is within this spiral arm of our Milky Way that the bright star cluster NGC 3603 resides. At the centre of the image is the constellation of Crux (The Southern Cross). The bright yellow/white star at the left of the image is Alpha Centauri, in fact a system of three stars, at a distance of about 4.4 light-years from Earth. The star Alpha Centauri C, Proxima Centauri, is the closest star to the Solar System. Credit: A. Fujii.

More recently, Stephen Baxter pretty much nailed Proxima Centauri b in his depiction of a just over one Earth-mass planet in the habitable zone called Per Ardua — this was in Baxter’s 2015 novel Proxima. Baxter’s planet was at 0.04 AU, and a little more massive than Earth; the real thing is 0.05 AU and 1.3 Earth masses. I would call that very nice work. Baxter has also noted, with considerable justification, that if we find a truly habitable planet in the very next system to our own, the implication is that such planets are quite common.

Image: This image of the sky around the bright star Alpha Centauri AB also shows the much fainter red dwarf star, Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Solar System. The picture was created from pictures forming part of the Digitized Sky Survey 2. The blue halo around Alpha Centauri AB is an artifact of the photographic process, the star is really pale yellow in colour like the Sun. Credit: Digitized Sky Survey 2. Acknowledgement: Davide De Martin/Mahdi Zamani.

Having been at the Breakthrough Starshot meetings all this week, I’m delighted to see that we now have a potential destination; i.e. an actual rather than assumed planet around one of the stars in the system nearest to us. Finding Proxima’s planet has been a long process, drilling down to the kind of measurements that can reveal its presence. Up until now we’ve been excluding larger planets in various kinds of orbits around Proxima, but the prospect of something Earth-sized in the habitable zone remained open. I hasten to add that Breakthrough Starshot has made no decisions about its target at this point, but it’s clear that Proxima b is going to be a prime contender.

I’m going to let Guillem Anglada-Escudé, head of the Pale Red Dot project, and his collaborators describe what his team has found. Noting that uneven sampling and the longer-term variability of the star are reasons why the signal could not be confirmed from the earlier data, the researchers go on to describe these key characteristics of the planet. From the paper:

The Doppler semi-amplitude of Proxima b (? 1.4 ms?1) is not particularly small compared to other reported planet candidates. The uneven and sparse sampling combined with longer-term variability of the star seem to be the reasons why the signal could not be unambiguously confirmed with pre-2016 rather than the amount of data accumulated.

And here’s what we’ve been waiting to hear:

The corresponding minimum planet mass is ? 1.3 M? . With a semi-major axis of ?0.05 AU, it lies squarely in the center of the classical habitable zone for Proxima. As mentioned earlier, the presence of another super-Earth mass planet cannot yet be ruled out at longer orbital periods and Doppler semi-amplitudes <3 ms ?1 . By numerical integration of some putative orbits, we verified that the presence of such an additional planet would not compromise the orbital stability of Proxima b.

Image: Guillem Anglada-Escudé, head of the Pale Red Dot project and lead author of the paper on the discovery of Proxima Centauri b.

And there we are, our first assessment of a planetary system around Proxima Centauri. The team’s analysis taps into previous Doppler measurements of Proxima Centauri coupled with the follow-up Pale Red Dot campaign of 2016. The Doppler data draws on the HARPS (High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher) spectrometer and UVES (the Ultraviolet and Visual Echelle Spectrograph). The search methods and signal assessment are thoroughly discussed in the paper (citation below). Key to the effort was what Anglada-Escudé and team call “[a] well isolated peak at ?11.2 days” that appeared in the pre-2016 Doppler data. The HARPS Pale Red Dot campaign was created to confirm or refute this 11.2-day signal. And confirm it they did.

Image: This artist’s impression shows a view of the surface of the planet Proxima b orbiting the red dwarf star Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Solar System. The double star Alpha Centauri AB also appears in the image to the upper-right of Proxima itself. Proxima b is a little more massive than the Earth and orbits in the habitable zone around Proxima Centauri, where the temperature is suitable for liquid water to exist on its surface. Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser.

We have a long way to go before knowing whether a planet around a red dwarf like this can truly be habitable. Tidal locking is always an issue because a planet this close to its host (Proxima Centauri b is on an 11.2-day orbit) is probably going to have one side fixed facing the star, the other in permanent night. There are papers arguing, however, that tidal lock does not prevent a stable atmosphere with global circulation and heat distribution from occurring.

And what about Proxima’s magnetic field? The average global magnetic flux is high compared to the Sun’s (600±150 Gauss vs. the Sun’s 1 G). Couple this with flare activity and there are scenarios where a planet gradually has its atmosphere stripped away. A strong planetary magnetic field could, however, prevent this erosion. Nor would X-rays (400 times the flux the Earth receives) necessarily destroy the planet’s ability to keep an atmosphere.

Image: An angular size comparison of how Proxima will appear in the sky seen from Proxima b, compared to how the Sun appears in our sky on Earth. Proxima is much smaller than the Sun, but Proxima b lies very close to its star. Credit: ESO/G. Coleman.

And then there’s the matter of the planet’s origins, and how that could affect what is found there. From the paper:

…forming Proxima b from in-situ disk material is implausible because disk models for small stars would contain less than 1 M Earth of solids within the central AU. Instead, either 1) the planet migrated in via type I migration, 2) planetary embryos migrated in and coalesced at the current planet’s orbit, or 3) pebbles/small planetesimals migrated via aerodynamic drag and later coagulated into a larger body. While migrated planets and embryos originating beyond the ice-line would be volatile rich, pebble migration would produce much drier worlds.

We can now hope for further data on Proxima Centauri b through transit searches, direct imaging and further spectroscopy. Ultimately, of course, we can think about the prospects of robotic exploration, the sort of thing we’ve been discussing here on Centauri Dreams for the last twelve years. No star is closer, and few will reward follow-up study more than this one. I need to get into a meeting and will have to let that wrap this up, but you can be sure there will be a lot more to say about Proxima and the entire Alpha Centauri system as the analysis continues.

The paper is Anglada-Escudé et al., “A terrestrial planet candidate in a temperate orbit around Proxima Centauri,” Nature 536 (25 August 2016), 437-440 (abstract).

Breakthrough Starshot Meetings

I’m at the Breakthrough Starshot meetings in San Francisco, with a full schedule indeed. As I did last time in Palo Alto, I won’t try to post daily because there just won’t be time, and in any case, I will need to go over my notes and consolidate my impressions. Even so, I plan to slip something interesting in here in the near future (keep an eye on Wednesday afternoon EDT), and will try to keep comment moderation active, though probably on a more infrequent basis than usual. Next week I’ll report in on what happened at the committee level at Breakthrough Starshot.

The Blue Spectres of Abyssal Europa

Claudio Flores Martinez has just finished an MSc at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg, Germany and is now enroute to a PhD in theoretical biology. He currently serves as a research assistant at the Developmental Biology Unit of EMBL and the University of Heidelberg’s Centre for Organismal Studies. With three papers in Acta Astronautica under his belt, Claudio is already deep into theoretical evolutionary biology, and in particular the contingency vs. convergence debate. In the paper below, he discusses how these issues couple with the possible emergence and development of life on Europa and the potential biosignatures by which we might find it, a journey that takes us deep into the nature of living systems. Just what might we encounter under that Europan ice?

by Claudio Flores Martinez

“Science is an endless search for truth. Any representation of reality we develop can be only partial. There is no finality, sometimes no single best representation. There is only deeper understanding, more revealing and enveloping representations. Scientific advance, then, is a succession of newer representations superseding older ones, either because an older one has run its course and is no longer a reliable guide for a field or because the newer one is more powerful, encompassing, and productive than its predecessor(s).”

— Carl R. Woese, “A New Biology for A New Century” (2004) [1]

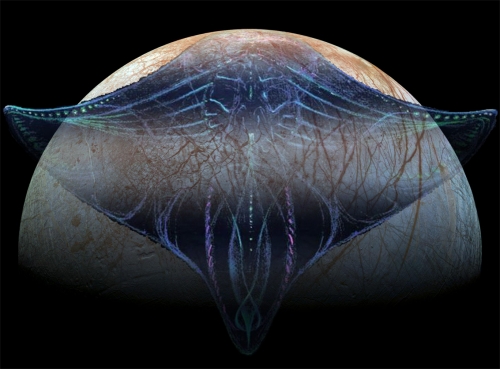

A useful Gedankenexperiment to ponder the implications of a putative alternate emergence of life on Jupiter’s moon Europa, is to adopt the perspective of a future field astrobiologist who finds himself submerged in the abyssal depths of an alien ocean, employing the technology of a far future embodiment of planetary bathy-nautics. Not relegating the complex process of biosignature detection to the highly advanced sensory equipment attached to his exosuit, we might wonder what it actually is that he sees beyond the other side of his metamaterial helmet visor? What is he going to observe as he is slowly drifting through the vitellus of the precious world egg mankind came to call Europa? Impelled to turn off the on-board lights by an inner voice, a transcendental moment of perfect stillness commences. Nothing moves out there.

Eternity, however, has not been reached yet. Our bathy-naut, let’s call him Castor for the present purpose, is still breathing, taking in the splendour of pure discovery. He has been trained for this task all along, but he is now checking his vital signs as he believes himself to be deceived by his sensory-deprived brain or some inorganic deep-sea type of ignes fatui – – – pinpoints of light are flaring up all around him as he is moving the arms of his mechanical exo-skeleton around in amazement. From the distance a bluish, fragile jelly-like creature is approaching, cloaked in sapphirine light. The luminosity of the Europan life form is increasing as it is getting closer, reminding him of the intense glow of the fusion plasma that accompanied their journey to the Outer System and, ultimately, brought them here. Reaching out with his right glove, cast in a pressure-proof titanium alloy, his mind is electrified by one thought alone: man – finally – has been handed the Promethean light – not in the form of fusion technology as so many have believed – but, instead, it is incarnate by the organic emanation of spectral blue bioluminescence…

Image: Is there a light shining in the eternally sunless ocean of Europa after all? Credit: JPL/NASA/Steve Burg (overlay of the composite “Galileo” imagery and 1988 artwork for James Cameron’s “The Abyss”)

INTRODUCTION

In the light of a potential discovery of extraterrestrial life through advanced robotic exploration (most likely on the icy moons of the outer Solar System, Europa and Enceladus) or astronomical observations, a future theory of universal biology, if it exists, should be able to make falsifiable predictions about the kind of biological activity such missions expect to encounter. To do so, current evolutionary thinking has to provide a comprehensive explanation of the convergent emergence of numerous adaptive traits that evolved independently and repeatedly across and within all three domains that make up the tree of life. Prime examples include distinct cellularization events in eubacteria and archaea, endosymbiosis, multicellularity, bioluminescence, echolocation, fusiform shapes and intelligent and social behavior in nonprimate species.

The long-term exploration strategy of Europa and its potential global subsurface ocean envisions the future in situ probing for life of the local aquatic environment with an integrated approach that uses a melt probe carrying a second-stage autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV). However, accurately predicting the exact nature of putative biological activity on Europa is extremely difficult. This is due to an unsolved and fundamental problem in theoretical evolutionary biology, namely the contingency vs. convergence debate. It is far from certain if stable trajectories exist, leading from mechanistically identical origins of life towards higher forms of biological organization, which are independently and repeatedly, and thus in a convergent manner, traced by the process of evolution within planetary biospheres apart from Earth. Therefore it appears to be helpful, first on theoretical grounds, to address the possibility of convergent evolution in two unrelated evolutionary systems that emerged and subsequently evolved and developed independently.

Recent studies indicate that convergent evolution is actually occurring on the molecular sequence level and, indeed, genome-wide in some instances. Information and (biological) systems theory are beginning to reframe the phenomenon of convergent evolution in terms of top-down causation and resulting functional equivalence classes. One instantiation of convergent evolution, bioluminescence, is especially well-suited for studying its underlying informational, genomic, functional and ecological basis. In addition, as we will see, bioluminescence is a promising candidate in terms of predictable higher-order biocomplexity that might have evolved in parallel on both Earth and Europa. Research on living light within terrestrial oceans can lay the theoretical and practical foundation for a dedicated agenda on defining potential biosignatures encountered within Europa’s subsurface ocean. Exploring the wonders of bioluminescence on the surface and in the depths of Earth’s oceans will facilitate the technology development of adequate robotic infrastructure that is needed to realize the dream of navigating an alien ocean.

COSMIC CONVERGENT EVOLUTION

Can science pin down universal attractors – on the level of biochemistry, function and morphology or even on ecological and cultural scales – within the unknown hyperspace or astrobiological landscape of biological potential? This fundamental question transcends the boundaries of any particular biological discipline and takes the issue of extraterrestrial evolution into the realms of philosophy, complexity theory and cosmology, opening up the way for an emerging scientific view of the Universe in which life is a natural and repeated cosmic phenomenon. The detection of a genuine second origin of life within our Solar System, imaginably on Jupiter?s icy moon Europa, or through a future success of the SETI enterprise could pave humanity?s way into a new era of universal scientific insight and recast its lonesome role within the cosmic scenery [2]. Far from being a contingent “cosmic accident”, as has been influentially suggested previously (for example by pioneer of molecular biology Jacques Monod and paleontologist Stephen J. Gould) life on Earth in general and Homo sapiens in particular can be reconceived of as natural and necessary outcomes of cosmic evolution, a process that is spanning almost infinite expanses of space and time, while, as will be argued here, being an inherent function, an adaptation of the living Universe, the Biocosm (a term taken from the magnificent work of James N. Gardner).

I am part of an international group of scientists, the Evo Devo Universe (EDU) research community, founded by systems theorist John Smart and philosopher Clément Vidal in 2008. We are seeking to envision, elaborate, discuss, test and promote a guiding vision for the emergence of a 21st century universal science of complexity that is able to reconcile thermodynamics with the onset of replication in the prebiotic realm, and to better understand the major transitions in evolution – from protocells to integrated nervous systems in multicellular organisms – as a necessary outcome of a cascading unfoldment, a process of universal complexification, and evolutionary development. Such processes may find their origin in the fundamental physical make-up of our Cosmos, the fabric of the observable Universe, whose threads, the laws of Nature, its DNA, we are beginning to unravel by means of our imagination, rational mind, simulation, and experimentation. Many researchers think of physics as the foundation for chemistry and biology. For the longest part of the past century or two this has been the case indeed. Now, however, we are getting first glimpses of the true vastness of networked biological complexity encapsulated in a single bacterial cell, exponentiated in multicellular life forms, staggering in the workings of our own minds, and, finally, transcended with the imminent advent, for better or worse, of autonomously reproducing and evolving technological replicators:

“The underlying paradigm for cosmology is theoretical physics. It has helped us understand much about universal space, time, energy, and matter, but does not presently connect strongly to the emergence of information, computation, life and mind. Fortunately, recent developments in cosmology, theoretical biology, evolutionary developmental biology, information and computation theory, and the complexity sciences are providing complementary yet isolated ways to understand our universe within a broader ‘meta-Darwinian’ framework in which contingent and selectionist or “evolutionary” and convergent, hierarchical, and replicative or “developmental” processes appear to generate complexity at multiple scales. The rigor, relevancy, and limits of an “evolutionary developmental” approach to understanding universal complexity remains an open and understudied domain of scientific and philosophical inquiry.”

— EDU’s mission statement (www.evodevouniverse.com)

A new expanded theory of evolution appears to be a prerequisite for the successful development of astrobiology and the complementary SETI studies. Here it will be outlined under the term Cosmic Convergent Evolution (CCE). The latter proposition, which is based on a growing volume of related literature, is a powerful updated view of life and a synthesis of evolutionary theorizing within the disciplines of astrobiology and cosmology, which contends that natural selection and evolutionary development in unison are a universal force of nature that might potentially lead to the emergence of similarly adapted life forms in analogous planetary biospheres.

First, the Universe may be envisioned as an evolving and, consequently, developing system. It might even comprise a replication cycle in which adaptive processes of its biological components occur to facilitate the generation and increase proliferation of these respective elements of the system and, eventually, enable replication of the Universe as a whole. During this process of cosmic ontogenesis the complexity of the system?s constituents increases naturally, and life and intelligence might be of paramount importance in catalyzing and structuring the emergence of a cosmologically extended biosphere. Redundancy of core regulatory and functional elements is a hallmark of any information-based replication system. Therefore, the universal replicator, or Biocosm, organizes itself in a way as to give rise to the repeated emergence of life and very likely, although less frequently, also to the evolution of highly advanced intelligence.

Second, in the continuing process of emerging biological complexity interplanetary and -stellar convergence could lead to predictable configurations in the fundamental organization of living matter. Just as there are attractors in physical phase space, biological systems might be biased towards a set of definable regions within the theoretical hyperspace of complexity.

The driving force behind interplanetary convergence is an assumed natural propensity of our Universe towards biogenesis. In such a scenario life should be emerging naturally as a complex far from-equilibrium phenomenon within aqueous environments that sustain geochemical energy gradients and offer the chemical building blocks for life as we know it. Further, recent theoretical (and some empirical) studies are starting to go beyond the “life is chemistry” paradigm by exploring how basic properties of biological systems, such as self-assembly, -organization, and replication, could be derived and quantitatively described by using fundamental physical laws, governing the state of any thermodynamic disequilibrium present in the physical world. Conversely, it is convincingly being argued that the potentialities of biological complexity might actually be able to constrain a completely new kind of physics [3].

Two distinct origins of life on Earth and, for example, Europa (resulting from a very similar prebiotic context) are by definition not identical in their genetic origin, but both are necessarily products of the same universal process – cosmic evolution. In this sense, separate events of biogenesis constitute convergent adaptations of a cosmologically extended biosphere, guided by an as of yet undiscovered natural principle of biogenicity. Just as the evolution of different species on Earth in environments which expose organisms to selective pressures of the same kind leads to the emergence of similarly adapted life forms, convergence across analogous planetary niches might result in predictable patterns of biological complexity. Adaptations of terrestrial organisms which repeatedly have been found to be convergent in nature, ranging from multicellularity to non-human intelligence, might be indicative of the robust evolution of comparable features in extraterrestrial life as well.

Through the ages speculative minds, often in mythological and sometimes in more naturalistic terms, have contemplated the idea of our own Universe being an organismic system. In the following I will argue that this idea is more than a mere theorem or speculation and, operating at the very forefront of scientific enquiry, is actually presenting us with falsifiable hypotheses that can be put to the test within this century. The possibility of a repeated and independent origin of life can be adequately described as a systemic property of a universal replicator that possesses a developmental cycle. Biological life proliferates at the onset of this sequence but might not prevail during later stages, which would be driven by a dramatic increase in cultural and technological complexity. Artificial forms of life and intelligence could be more apt in completing the cycle. A growing number of futurists are arguing that humanity’s developmental transition will occur within the 21st century and that a “Singularity”-type event will prove the reality of an Evo Devo Universe or Biocosm (consider for example John Smart’s daringly innovative “Transcension Hypothesis” [4]).

Personally, however, I am more inclined to view the Promethean plight fulfilled by clearly establishing the organic convergence between life on Earth and another celestial body. Ultimately, as the truly open-minded scientists that we profess to be, we should consider – tentatively – what a continued failure of robotic and astronomical astrobiological exploration within the Solar System and beyond, as well as an absent merger with the machine in the future, would imply about the nature of the reality we find ourselves in.

Ending this philosophical excursion on an optimistic note I would like to remind the readers of the introductory quote by Carl R. Woese, whom I consider to be one of the greatest but least known pioneers of biology from the 20th century (NASA established the “Institute for Universal Biology” in his honor). I herewith humbly submit that “Cosmic Convergent Evolution” might be a “more revealing and enveloping representation” for the emergence, evolution and development of biological complexity on Earth and, by extension, throughout the Cosmos.

ORIGIN OF LIFE, MINIMAL CONVERGENT TRAITS AND BIOSIGNATURES

In order to better understand how the most basic entity, which we could identify as a living organism, should look like, let us turn to the origin of biological evolution again. Life on Earth has evolved in a manner suggestive of a minimum set of prerequisites which comprises liquid water, biogenic elements (C, H, N, O, P, and S) and biologically usable energy (i.e. transducible into chemical bonds for storage and later usage in metabolic reactions). In regard to the most pressing constraint for the onset of a potential biosphere on Europa, for instance, namely available energy sources, recent studies including theoretical work and on-going hydrothermal laboratory experimentation have stressed the importance of evolutionarily conserved molecular “disequilibrium converting engines” in the proto-metabolism of early terrestrial life.

This work is part of the “Submarine Hydrothermal Alkaline Spring Theory” for the emergence of life [5]. It posits that off-ridge alkaline hydrothermal springs reacted with the metal-rich carbonic Hadean Ocean. During this reaction compounds such as hydrogen, methane and ammonia, as well as calcium and traces of acetate, molybdenum and tungsten were released by progressing serpentinization of ultramafic rock, thereby offering a sustained source of chemically transducible energy for early biological systems. Employing an ancient molecular apparatus resembling the ATP synthase complex, universally observed in extant life, to harvest the free energy contained in the resulting proton and redox gradients, these ancestral organisms could have been able to maintain and gradually increase the complexity of their metabolic and replicator systems. Assuming that conditions during the late stages of Europa?s planetary differentiation might have been comparable to Earth?s Hadean Ocean in terms of a rocky mantle exchanging chemicals and heat with an overlying slightly acidic water layer, many studies point at the importance of putative hydrothermal circulation systems as possible environments conducive to an alternative origin of life.

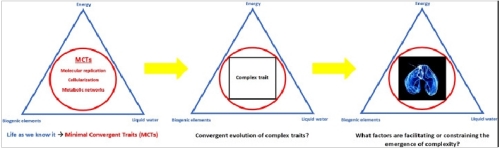

In analogy to the triad of parameters that is defining habitability for life as we know it, I introduced a framework for constraining the biocomplexity of putative alien biological systems [6]. Just as a given world must possess three basic requirements (liquid water, biogenic elements and an energy source) to be rendered habitable, biological entities that we could identify as such, should display three universal Minimal Convergent Traits (MCTs): 1) molecular replication and inheritance, 2) cellularization via membrane systems and 3) metabolic networks coupling energetically favorable biochemical reactions. These MCTs represent systemic properties of an alien organism. It is not implied, however, that extraterrestrial biology necessarily employs an identical set of molecules known from terrestrial life to sustain these features. In any case, if one of these traits is lacking in extraterrestrial organisms, we could not recognize them as life as we know it (and they would not be viable according to our current understanding of biology in the first place).

Image: Constraining putative alien biocomplexity by introducing Minimal Convergent Traits (MCTs): molecular replication, cellularization and metabolic networks. MCTs represent systemic properties rather than molecular identities. They delineate the phase space of potential higher-order evolutionary innovation on Europa. Figure from (Flores Martinez 2015) [6]

Research on the origin of life on Earth can give valuable insights into the principle mechanisms that molecule assemblies that instantiate MCTs have to be able to carry out, such as autocatalytic processes of self-replication. It is easier to reasonably predict complex or systemic properties of extraterrestrial life, like the previously mentioned characteristics of molecular replication, cellular organization and metabolic networks, than to anticipate the exact types of molecules involved in these functions. It is at the level of sufficiently advanced complexity of living systems at which the hypothesis of CCE proposes an evolutionary robustness of certain basic traits, like cellularization, and even higher evolved adaptations, for instance bioluminescence, among earthly and alien life. Generally, a universal mechanism which allows, first, the emergence of life on a given world and then, second, shapes its evolution according to commonly shared evolutionary trajectories toward increased biological complexity could be termed substrate-independent convergent evolution.

Such a definition does not imply that alien life can emerge from a more or less random variety of chemical elements. Almost certainly it would be based on carbon and organic molecules known from terrestrial biology. However, the specific substrates of the cellular replication and membrane components could be constituted by different biopolymers than those present in terrestrial organisms. One example for such a kind of convergence on Earth is the repeated emergence of cell membranes in archaea based on glycerol-ether lipids with isoprenoid sidechains rather than glycerol-ester lipids composed of fatty acid tails as found in eubacteria and eukarya.

Nevertheless, already on the level of proteins and their enzymatic functions it is difficult to imagine equally effective bio-catalytic molecular complexes. Whether molecular evolution on another world necessarily encompasses a hierarchical flow of genetic information starting from a replicating information-saving molecule (DNA) that gets transcribed into a messenger molecule (RNA) which in turn forms the basis for the eventual translation of the required cellular constituents, corresponding to terrestrial proteins, cannot be known with absolute certainty. For any biologist, on the other hand, it is hard to envision a similarly ingenious form of regulatory organization of genetic information, allowing multi-level tweaking of cellular processes. Given the integration of multiple molecule assemblies into functional networks in extraterrestrial cells, convergence of biological organization on a very profound level would become apparent.

According to NASA’s 2008 astrobiology roadmap a biosignature is defined as: “an object, substance and/or pattern whose origin specifically requires a biological agent. The usefulness of a biosignature is determined, not only by the probability of life creating it, but also by the improbability of nonbiological processes producing it. An example of such a biosignature might be complex organic molecules and/or structures whose formation is virtually unachievable in the absence of life. A potential biosignature is a feature that is consistent with biological processes…”. Future planetary exploration missions and spectroscopic exoplanet surveys will be limited due to a maximum volume available for scientific payload and highly sought-after observation time. Dedicated astrobiological space exploration is therefore dependent on a selection of previously chosen indicators for the presence of extraterrestrial life. More precisely, these indicators could be termed convergent biosignatures, as the mentioned instrumentation will scan for markers analogous to phenomena observed in terrestrial biota [7].

MCTs should suffice to delineate universal features of alien (microbial) life. More complex adaptations could be derived from this baseline by considering planetary properties of the search target. As already described, universal features of any kind of extraterrestrial life encompass: molecular replication, cellularization and metabolic networks. From these systemic properties more precise convergent biosignatures, i.e. potential molecular identities, can subsequently be deduced. Exactly this type of predictability is essential to the astrobiological endeavor, because future planetary exploration missions or space-telescope based exoplanet surveys need to be guided by a defined, or at least constrained, set of possible biosignatures. Here it will be argued that the notion of convergent evolution is pivotal in lending a certain degree of predictability to astrobiology and the related SETI field. Luckily, I have been already part of a pioneering lander mission design study for future in situ exploration of the plume fractures found on Enceladus [8]. The organizational scheme of MCTs adequately fits routine procedures in space mission design, namely the overarching science goal definition process via “science traceability matrices” (STMs) connecting science goal, science objectives, measurements, and detection methods in a logical and modular fashion.

| Science goal | Science objectives | Measurements | Detection methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| In situ probing of an aquiferous fracture to search for biosignatures | Molecular replication | Analyze water sample for presence of replicatory polynucleotides | Antibody microarray/sequencing; Nanopore-based instruments |

| Cellularization | Analyze water sample for presence of cellular structures and membrane material | Microscopy Flow cytometry Fatty acid markers Mass spectrometry |

|

| Metabolic networks | Analyze water sample for presence of expected metabolic products (CH4) | Mass spectrometry |

Science Traceability Matrix (STM) for a lander mission to Enceladus based on dedicated astrobiology science objectives (= MCTs). Instrument selection will be constrained by a logical and modular workflow according to the overarching science goal. Figure from (Konstantinidis et al. 2015) [8]

TOP-DOWN CAUSATION, INFORMATION HIERARCHIES AND MODULARITY

On an abstract systems theoretical level convergent evolution of organismal complexity is the result of biomolecular networks that are organized and structured by information hierarchies via top-down causation. The emergence of fundamental network properties such as modularity and the related phenomenon of functional equivalence classes of lower level operations or subroutines – both in biological and technological systems – can be explained as a corollary of top-down organized information hierarchies.

Top-down causation refers to the causal role of information in living systems. More specifically, it describes the process whereby “higher levels of organization in structural

hierarchies constrain the dynamics of lower levels of organization” [9]. Top-down theorists (e.g. Arizona State University physicist Sara I. Walker who is leading ASU’s “Emergence” group and has contributed a number of highly innovative and inspiring papers) propose that the organization, structure and function of living systems cannot be completely explained by a reductionist “bottom-up” approach. In the latter case it is assumed that purely physical effects determine the dynamics of lower levels of organization and, by extension, strictly govern interactions occurring at higher levels as well. Information, however, can acquire a causally efficacious role in physical systems without violating “the principle of the closure of the physical world” [10]. In fact, an emerging school of thought in evolutionary biology is advancing the hypothesis that the transition from non-life to life, abiogenesis, can be aptly described as a transition in causation and information flow:

“Transitions in causal architecture could have occurred through a series of “information takeover” events, which differ from the notion of “genetic takeover” in that they are not necessarily confined to the transfer of genetic information from one molecular species to another. Instead, information takeover refers to transitions in chemical complexity whereby advances in information processing and computation would have conferred nascent life with the logical architecture necessary to gain control over the chemical substrates in which it was instantiated. These transitions will likely be difficult to identify, however one key feature should be that the (informational) states of a nascent living systems played an increasingly prominent role in determining the future dynamics. This suggests that the processes leading to the emergence of life should be marked by a series of “information take-over” events corresponding to changes in causal architecture and information flow, which, in principle, is measurable.” [9]

Emerging life on Europa, by definition, should have underwent a similar “information takeover” event and this unexplored mechanism by which information is gaining a causally efficacious role in physical systems constitutes the most fundamental convergent evolutionary process imaginable in the realm of biological complexity. Without delving into the philosophical implications of such phenomena too far, I am definitely not viewing “information takeover” events as contingent happenstance. They rather represent necessary transmutations or transitions in the overall complex organization of the observable Universe. I challenge every contingency-oriented naysayer to consider these cutting-edge theories on the origin of life and to provide a coherent theoretical framework in which life can still be explained as a “cosmic accident”.

Informational takeover events appear to have occurred during all of the major transitions in evolution. At any given higher level of biological complexity novel top-down informational hierarchies are defining lower level molecular, cellular or organismal operations. This idea is closely related to the concept of functional equivalence classes:

“Top-down causation operates through functional equivalence classes. Functional equivalence occurs when a given “higher-level” state leads to the same high-level outcome, independent of which “lower-level” state instantiates it. Equivalence classes are defined in terms of their function, not their particular physical instantiation: operations are considered (functionally) equivalent (i.e., in the same equivalence class) if they produce the same outcome for different lower-level mechanisms. Functional equivalence classes therefore represent the physical manifestations of virtual constructors. Functional equivalence is evident, for example, in the case of convergent evolution presented above, where convergence occurs because natural selection optimizes a functionally equivalent outcome (in this case, echolocation).” [9]

Clearly, the proposed MCTs that could potentially constrain the selection of future biosignature detectors constitute a practical application of the top-down causation via functional equivalence class paradigm. Accordingly, each MCT represents a fundamentally organismal functional equivalence class, performing core cellular operations, which can be instantiated, imaginably, by a multitude of different functionally interchangeable biopolymer or metabolic networks. In terrestrial organisms the MCT of molecular replication is instantiated by DNA (although DNA cannot, of course, replicate on its own, it needs RNA and protein “co-factors”). However, for the present purpose it suffices to define DNA as the main molecular information deposit that gets copied during the process of cellular reproduction. Contrary to neo-Darwinian dogma top-down causation can influence genome evolution in a non-random way as evidenced by convergent changes in hundreds of mutations that benefit the functional emergence of a trait that can serve as a direct adaptation to a specific environmental context. The genomic study on echolocation in dolphins and bats [11] referenced in the cited paragraphs above and below is one of a growing number of publications that begin to assess the wonders of convergent evolution on a genomic scale and its impact on the emergence of evolutionary novelties:

“Top-down causation is an important mechanism for adaptive evolution through natural selection, where the higher-level “goal” is survival. The role of top-down causation in adaptive selection is particularly evident for cases of convergent evolution. A striking example is provided by the evolution of echolocation in dolphins and bats, where over 200 genes have independently changed in the same ways to confer both species with the ability to use sonar. A common high-level selection pressure (e.g., for the ability to navigate) lead independently to the same specific mutations in the DNA of both species. Convergent evolution thus provides a clear example of top-down causation via adaptive selection, where causal influences run from macroscopic environmental context to microscopic biochemical structure.” [9]

Another remarkable example how function is shaping genome evolution is the convergent expansion of the proto-cadherin protein family between the invertebrate octopus and vertebrates allowing for increased neuronal complexity in each respective evolutionary lineage, a finding that was revealed by a recent sequencing effort [12]. We are just beginning our quest in understanding how the emergence of a certain biological function, in this case synaptic/neuronal signalling, is “driving” large-scale genomic rearrangements that go well beyond what is commonly understood as “mutational” or “gene duplication” events.

Yet an even more illustrative phenomenon showing how biological complexity is governed by top-down causation is the regulation of gene expression by the so called epigenome. Genomic information is stored in a physical object, DNA. The entirety of DNA in a given organism is constituted by its genome. Nonetheless, the genome does not contain the complete information on how, when and to what extent certain genes should be expressed or repressed. This critical cellular information is instantiated in the epigenome. While the epigenome is associated with certain non-DNA molecular sequences (e.g. histone modifications), it should be rather viewed as a “… global, systemic, entity” whose “… real-time operation …lies in the realm of nonlinear bifurcations, interlocking feedback loops, distributed networks, top-down causation and other concepts familiar from the complex systems theory.” [13].

It should be quite clear to any researcher working in the biosciences today that – quite paradoxically – the “central dogma” of molecular biology (unidirectional information flow from DNA RNA protein) is not compatible with biological reality. Therefore biologists are beginning to think along the lines of “information hierarchies” instead of the “central dogma”. Information hierarchies allow for bidirectional information flow from higher to lower levels of biological organization. Yet, bidirectional information flow does not imply equivalence of each respective structural level in regulating biological systems. For this reason have the causal relationships responsible for the homeostasis of a particular organizational instance been termed “informational hierarchies”, as higher levels are constraining the dynamics of lower levels via information control, processing and selection.

Different molecules become coupled via information selection during biological network constitution as they are carrying out a specific cellular operation. In terms of network topology this process is leading to the formation of hubs, i.e. regulatory molecules forming edges (interactions) with other molecules (nodes) within a group and fewer edges with other groups (that are built around their own particular hub). The result is the hierarchical and modular organization observed in many biomolecular networks, prime examples being gene regulatory and metabolic networks. Hierarchical modular networks display self-similarity: many highly integrated small modules group into a few larger modules, which in turn can be integrated into even larger modules. Consequently, metabolic and gene regulatory networks are grouped into several large modules, which are further partitioned into smaller, but more integrated submodules (for a mathematical description see [14]).

Image: Life’s complexity pyramid. Biological systems are governed by hierarchical, modular biomolecular networks that display large-scale self-similar organization. Organismal molecular information is highly specific while the overall embodied structures encoded within these instructions show recurring patterns universally expressed at any given level of biocomplexity. Figure from (Oltvai and Barabasi 2002) [15]

Lastly, the profound functional similarities in the large-scale organization of biological and technological complex adaptive systems are pointing toward as of yet undiscovered ordering principles underlying physical reality that can be framed within a future integrative framework based on top-down causation and convergent evolution:

“Advanced technologies and biology have extremely different physical implementations, but they are far more alike in systems-level organization than is widely appreciated. Convergent evolution in both domains produces modular architectures that are composed of elaborate hierarchies of protocols and layers of feedback regulation, are driven by demand for robustness to uncertain environments, and use often imprecise components. This complexity may be largely hidden in idealized laboratory settings and in normal operation, becoming conspicuous only when contributing to rare cascading failures. These puzzling and paradoxical features are neither accidental nor artificial, but derive from a deep and necessary interplay between complexity and robustness, modularity, feedback, and fragility.” [16]

ADVANCED BIOCOMPLEXITY ON EUROPA

Next to the water column and seafloor of the deep sea, its underlying sediment presents the largest potential habitat on Earth. On Europa and Enceladus the interaction between the rocky mantle and the overlying water column could lead to hydrothermal processes which may drive the exchange of energy and biogenic elements. In regard to putative hydrothermal systems on these moons, especially in the case of Europa since it is considerably larger than Enceladus, it is conceivable that the previously mentioned serpentinization, a hydro-geological process well-known from certain areas of ultramafic terrestrial seafloor, might provide an energy and chemically rich environment. Thermal cracking of Europa?s crust caused by progressing serpentinization of ultramafic seafloor, a mantle composition that is consistent with models of Europa?s planetary differentiation might reach up to 25 km into the mantle releasing large quantities of molecular hydrogen. This could allow for a putative H2-driven biosphere of microorganisms capable of exploiting chemical rather than solar energy for their biosynthetic and metabolic processes.

Based on these findings we can expand our notion of habitability of icy satellites from the subsurface ocean and seafloor regions down into the mantle itself, where serpentinization reactions potentially fuel a microbial biosphere. Given that this microbial biosphere extends to the seafloor where hydrothermal systems are representing an interface between the ocean and mantle geochemistry, we can start to reasonably assume the existence of simple ecosystems based on chemoautotrophic microorganisms. How this type of unicellular life, often found in a symbiotic relationship with various multicellular species, is giving rise to complex ecosystems has been best studied at hydrothermal vent sites across the mid-ocean ridges of our planet. Global heat output models for Europa have shown that hydrothermal systems could in theory support energy fluxes roughly in the range of terrestrial activity.

Additionally, another important process that might enable the emergence of complex life beyond the unicellular stage on Europa is the transport of radiolytically produced hydrogen peroxide from the surface down into the ocean, where it would disintegrate into H2 and O2. Calculations which linked the amounts of potentially available O2 to the length of the delivery period of H2O2 from the surface to the ocean showed that upper limit abundances of hydrogen peroxide might lead to O2 concentrations above those of terrestrial oceanic O2 minimum zones within a turnover time of 10–110 Ma. Estimates of mean surface age of 30–70 Ma thus allow the possibility of oxygenated upper ocean layers. The latest spectroscopic assessment of H2O2 abundances on Europa?s surface using Earth-based adaptive optic systems lowered high-end estimates but nevertheless allows for considerable amounts of dissolved oxygen inside the ocean if mixing occurs. Further spectroscopic analysis carried out by the same researchers has led to the detection of a previously unknown surface component, the magnesium sulfate salt epsomite. As magnesium is unlikely to be an endogenous constituent of the surface it probably originates from oceanic magnesium-chloride reaching the surface and reacting with previously present sulfate compounds.

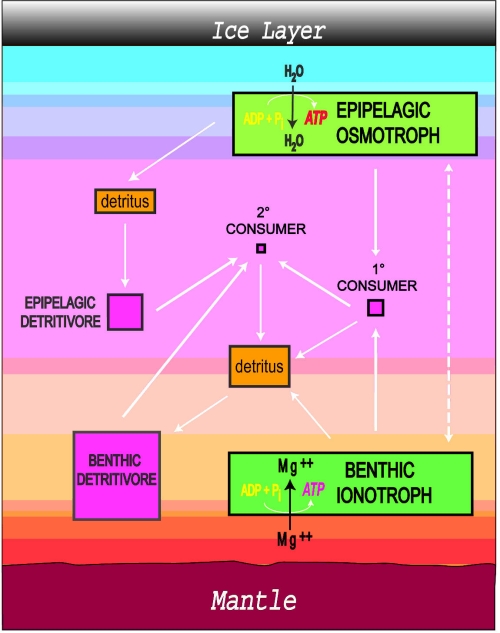

A recent paper from the well-known JPL researchers Steve Vance, Kevin Hand and Robert Pappalardo largely confirms the previously calculated estimates of H2 and O2 abundances, thereby stressing again Europa’s potential for the emergence and perpetuation of life in terms of geochemical energy disequilibria over the entire planetary history [17]. Hence it is tempting to consider hydrothermal vents not only as a potential environment for a second genesis of life on Europa, but also to think about them as enduring habitats for biological activity from which simple microbial life is possibly evolving towards higher complexity into multicellular organisms that over time become endogenous to the overlying water column and ice/ocean interface. Convection currents would be able to carry away microorganisms from their native seafloor safe haven into harsher environments where their survival would depend on the evolution of novel energy transduction mechanisms. Given the unprecedented adaptive versatility of microorganisms from Earth and the unforgiving selective pressures within Europa?s dark ocean this does not seem entirely unlikely. Ecosystem modeling approaches for Europa based in one case on methanogenesis, a known pathway employed by terrestrial chemoautotrophs, and in the other on a hypothetical energy transduction mechanism (ionotrophy), has yielded theoretical absolute biomass abundances that would be high enough to sustain complex and differentiated ecological networks comprising producers, primary, secondary and tertiary consumers and detritivores in analogy to terrestrial marine ecosystems [18]. In this model the tertiary consumers and benthic detritivores are comparable in size to terrestrial tadpoles and brine shrimp.

Consequently, the existence of macrofauna on Europa should not be discarded a priori. Quite on the contrary, the emergence of multicellularity, a remarkable example of convergent evolution, within a sustained biosphere of microbial chemoautotrophs seems not impossible at all. However, it should be noted that the emergence of multicellularity, as we know it from Earth, requires another important macroevolutionary step. First of all, cell types with an increased genomic complexity, eukaryote-like organisms, need to arise. Interestingly, on Earth this transition happened only once (thereby being one of the bona fide evolutionary bottlenecks in the emergence of higher-order biocomplexity; however we cannot exclude that now extinct alternative eukaryote-like cell designs might have existed at some point in Earth’s history). Then again, secondary endosymbiotic events among eukaryotes occurred repeatedly in a convergent manner. Subsequently, these complex unicellular organisms, repeatedly and independently, turned multicellular nearly forty times in aerobic environments – a prime example of convergent evolution.

Image: Complex ecosystems might be thriving hidden beneath Europa’s ice shell. Figure from (Irwin and Schulze-Makuch 2003) [18]

LIVING LIGHTS OF THE ABYSS

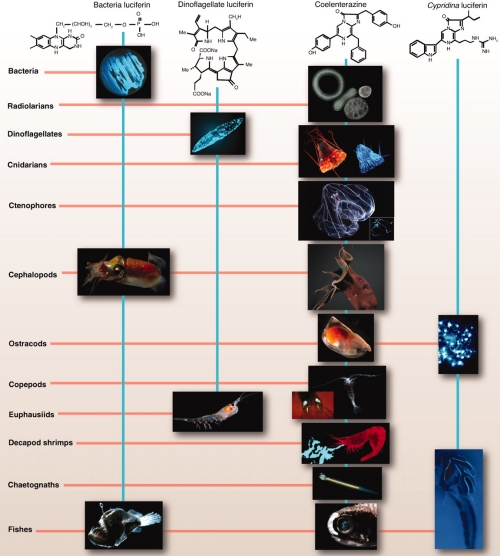

Contemplating how terrestrial deep-sea ecosystems are organized and which functional adaptations are widely common among marine organisms we are drawn towards the mesmerizing beauty of bioluminescence. As already noted the phenomenon of bioluminescence is one of the most striking examples of convergent evolution. A basic bioluminescent system contains a light-producing substrate, the luciferin, and an enzyme, the luciferase, which catalyzes an oxidative reaction that leads to the emission of photons in the spectrum of visible light with most luminescence between 450 – 635 nm. In the oceanic world most bioluminescence emitted lies in the blue spectrum, since these wavelengths are travelling farthest in water. The particular type of bioluminescent chemical reaction is strictly dependent on the presence of O2. Many groups of bioluminescent organisms share a common substrate for their light-producing biochemical reactions but independently evolved specific enzymes for catalysis. Bioluminescence mediates fundamental ecological functions including the search for food, attraction of sexual partners and evasion of predators. However, not only multicellular organisms are bioluminescent but also unicellular bacteria and eukaryotes.

Ecosystems inside Europa’s ocean might be organized by bioluminescence on a fundamental level. In upper highly oxygenated oceanic layers bioluminescence might be a wide-spread adaptation of multicellular organisms whose survival is dependent on the location of prey and the attraction of species members for reproduction. However, unicellular life on Europa might also be adapted in an analogous way. On Earth bioluminescent bacteria are often found in symbiosis with more complex organisms such as fish and squid. Coevolution has led to highly differentiated organs containing bioluminescent bacteria that can be moved, focused and activated in response to certain stimuli. Symbiosis between uni- and multicellular life would be very likely in a biosphere on Europa since evolution on Earth has been profoundly shaped by such organismic relationships.

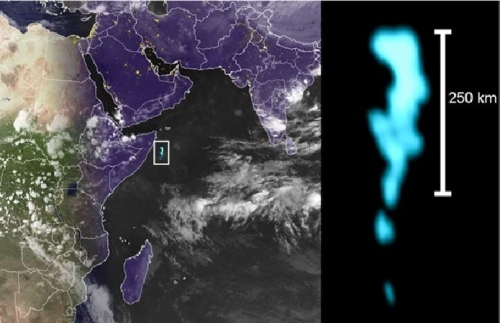

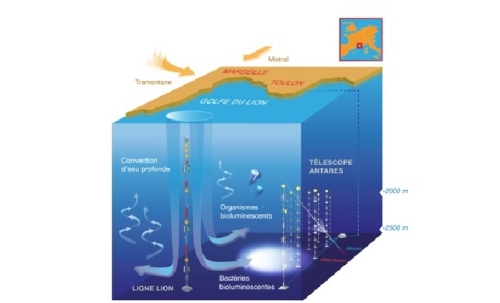

The credit for the first ever mention of bioluminescence as a spectral signature of life in astrobiological exploration goes to MIT exoplanet hunter Sara Seager [19]. She suggested that far-future space telescopes might be able to detect the light signature of gigantic bioluminescent blooms on the surface of distant ocean worlds. On Earth vast blooms of unicellular luminescent bacteria are responsible for so called “milky seas” that have been detected via remote sensing from space [20]. In microbial blooms bioluminescence is the product of quorum sensing which represents an elaborated mechanism allowing bacteria to modulate gene expression and eventually population density. However, quorum sensing is coordinated by chemical signaling and the function of the luminescent response in freefloating blooms of microbes remains to be determined. In a fascinating twist one very advanced, but Earth-bound, telescope actually has detected bioluminescence as signature of life already – as a side-product of astronomical observations. The photo-multipliers of the deep-sea neutrino telescope ANTARES, located in the Mediterranean See, recorded seasonal spikes in ambient luminescence that were subsequently attributed to the activity of enormous underwater blooms of a newly characterized strain of deep sea microbes, Photobacterium phosphoreum ANT-2200 [21].

Top image: satellite image of a “milky sea” off the coast of Somalia. Bottom: deep-sea bloom of bioluminescent bacteria detected by the Antares neutrino telescope in the Golfe du Lion, France. Image Credit: Steve Miller/NRL/Mathilde Destelle

Bioluminescence as a new type of biosignature for future exploration of Europa within our own Solar System was proposed by myself at the 64th International Astronautical Congress in Beijing for the first time in 2013. My subsequent theoretical work on this concept was mostly related to assessing the stability – or evolutionary robustness – of bioluminescence as an independently and repeatedly evolved evolutionary trait in phylogenetically distantly related organisms. The latest genomic analyses on early animal evolution confirm that bioluminescence is one of the most ancient functional adaptions in multicellular organisms and a recent study has reassessed the previously underestimated diversity of bioluminescent systems among fishes. As will be explained further below bioluminescence can also serve as an excellent example to explain adaptive evolutionary processes in terms of top-down causation, information hierarchies and functional equivalence classes.

Image: Presenting “Cosmic Convergent Evolution of Bioluminescence on Europa” at the 64th International Astronautical Congress in Beijing, 2013. I am the fifth person from the right, next to former ESA Director General Jean-Jacques Dordain. My conference stay was sponsored by ESA’s “IAC Student Participation Programme”. Image Credit: ESA

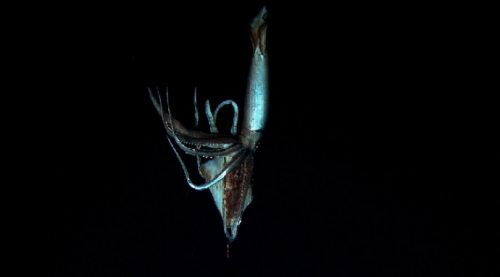

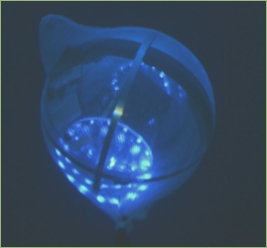

The idea of bioluminescence as biosignature is corroborated by novel deep-sea exploration techniques employed in terrestrial oceans that were highly successful within the last decade in identifying a number of previously unknown species. In 2012 the “optical luring” approach developed by Edith Widder allowed for the first detailed video footage of the giant squid, Architeuthis dux, in its natural habitat. This unobtrusive exploration method uses a spherical probe equipped with an array of LED lights that gets lowered into the ocean depths. The probe is called the “electronic jellyfish” because it emulates the spectacular blue bioluminescence pattern of the deep-sea dwelling species Atolla wyvillei. The biomimetic probe is attached to a silent camera system which illuminates the surrounding with far red light because this range of the spectrum is not visible to most deep-sea organisms. Another kind of detection method for bioluminescence has been development in the form of so called bathy-photometers. These devices are made up of flow chambers that are coupled to photomultiplier tubes for measuring the intensity of mechanically stimulated bioluminescence of unicellular organisms. A number of modularized off-the-shelve bathy-photometers is available and can be attached to the latest AUV platforms. This allows for long-range, uninterrupted bioluminescence measurements in varying depths. Another platform that has been developed with the dedicated goal of exploring bioluminescence in deep waters (up to 300 m) is the “Exosuit”, a kind of wearable submarine. Bioluminescence systems of undiscovered species might be used in future medical diagnostic procedures. It made its maiden voyage during an underwater archaeology expedition to the Antikythera site, Greece, in 2014.

Image: The “Exosuit”: taking the spacewalk experience underwater. Image credit: Brett Seymour

On Europa, a submersible robotic exploration vessel could be equipped with highly miniaturized bathy-photometers that would scan for ambient bioluminescence primarily emitted by microorganisms while the optical luring approach, based on its terrestrial counterpart, would target complex multicellular life. Biologically produced light is a far more readily detectable signature of life than for example complex biopolymers are. The biological origin of these compounds can only be verified through multistep chemical analyses, which always bear the danger of a false positive. Thus, the presence of living light inside the ocean of Europa is the most unambiguous sign of biological activity. It can emerge in both uni- and even multicellular organisms as a necessary outcome of the evolutionary process that is determined by the planetary properties of Europa (submarine alkaline hydrothermal vent origin of life and ongoing oxygenation throughout its history).

Top image: still from the video that captured the giant squid for the first time. Middle: successful luring of the deep-sea creature with the biomimetic probe. Bottom: “electronic jellyfish” emulating bioluminescence patterns. Image Credit: Reuters/Discovery Channel/Edith Widder

Until now, however, the evolutionary origins of bioluminescence in terrestrial oceans are not completely resolved. One well-founded hypothesis, initially posited in the 1960s, suggests that biological light had its beginning as an ancient oxygen defense mechanism following the onset of the first “great oxidation event” (GOE) approximately 2400 Ma ago. Before the continuous rise of atmospheric and oceanic O2 concentrations due to the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis in ancestral cyanobacteria, all life on Earth had an anaerobic metabolism. Concentrations of O2 remained relatively low for about 1600 Ma until 800 – 400 Ma ago levels reached half or more of present-day values. This drastic increase in available oxygen occurred simultaneously with the Cambrian Explosion during which the greatest diversification of terrestrial life so far took place. When the ancient oceans were oxygenated in small amounts for the first time after the GOE, chemically reactive O2 species like hydrogen peroxide, singlet oxygen, superoxide and oxygen radicals formed which were highly toxic to the then extant life. It is possible that functional luciferin/luciferase systems evolved during this time, consuming ambient excess oxygen, to prevent the adverse effects of the newly introduced oxidative agents. As a nonfunctional by-product of these reactions bioluminescent light was produced. Within the ancient oceans of Earth all organisms would have been exposed to the same selective pressure, the threat of damaging oxidative reactions, and different species probably employed unrelated chemical systems in their individually evolving bioluminescence.

Once again, we can turn to the previously elaborated theoretical framework underlying convergent evolution via top-down causation. In the same way that MCTs should encompass fundamental systemic properties of alien life forms that could potentially be instantiated by alternative biochemistries, bioluminescence represents an envisioned stable functional state beyond the “minimal convergent” level of biological complexity. Specifically, it is dependent on the presence of oxygen inside the ocean of Europa. If our models on Europa’s geochemistry hold true, ongoing oxygenation would have surely presented a high-level selective pressure in the form of rising oxygen concentrations. This would allow for an evolutionary scenario “where causal influences run from macroscopic environmental context to microscopic biochemical structure” [9]. Thus, such causal influences would lead to the convergent evolution of bioluminescence across Europan biota through top-down causation via adaptive selection. The production of biological light would present a higher-order functional equivalence class that could be instantiated by a number of different biochemical reaction systems, as evidenced by the disparate mechanisms employed by terrestrial organisms. On one hand, potentially further constraining the exact biochemistry underlying bioluminescence on Europa could be a future research goal; on the other, future biosignature detectors for biological light can be designed irrespective of the lower level operational molecular embodiment. Therefore, in a very practical but also in an almost mystical sense, bio-photonic light appears to transcend its particular substratum.

Image: Phylogenetic distribution of marine bioluminescence across a number of uni- and multicellular phyla. This scheme nicely illustrates how bioluminescence as an adaptive organismal trait is linked to the concept of functional equivalence classes. Biological light can be instantiated by a number of different chemical systems based on, sometimes, shared substrates but individually evolved catalytic enzymes: the essence of convergent evolution. Figure from (Widder 2010) [22]

After the first one and a half billion years or so after the GOE, probably only bacterial microorganisms were adapted in such a way since eukaryotes had not yet entered the evolutionary scenery. Still, luciferases could have provided an adequate oxygen protection mechanism for these more complex cells as well. After all, the specific luciferases of modern-day organisms like jellyfish, for example, are not related to bacterial enzymes. Accordingly, their bioluminescent systems emerged independently from each other by way of convergent evolution. Sometime before the Cambrian Explosion, after the oceanic oxygenation had immensely progressed and incipient multicellular animal life did not rely on luciferases as their primary oxygen defense anymore (more efficient means of detoxification certainly evolved in parallel), a decisive shift of selective pressure secured the fate of bioluminescence as a functional adaptation. Luciferin/luciferase systems would have lost their selective value and eventually been lost in the presence of equally or more effective oxygen defense if not another function of the biologically produced light was subsequently being selected for. Obviously, such co-opting of the function of bioluminescence depended on the pre-existence of light-detecting or rudimentary visual systems capable of detecting the emitted light. How could such biological adaptations, which on Earth evolved in constant interaction with the solar flux, emerge in the pitch-black abyss of Europa?

Light-detecting sensory adaptations are very common throughout the animal kingdom and the underlying mechanism is highly conserved – from the eyespot of the algae Euglena to complex imaging camera eyes of humans and octopus. Vision is always mediated by photoreceptor cells employing rhodopsin-like photopigments linked to G-protein cascades. Photon-induced cis-trans isomerization of retinal (opsin + retinal = rhodopsin) is the first step in an elaborated second messenger pathway which is responsible for the transduction of the sensory stimulus into electrical signals. Functional photoreceptors using this kind of light-detection and phototransduction apparatus were already in place more than 600 Ma ago before the major branching of animal phylogeny. The basic mechanism underlying light-detection, however, has been repurposed independently several times in the evolution of animals. This lead to the emergence of eyes in jellyfish (in rudimentary form) and complex camera eyes in invertebrates (e.g. octopus) and vertebrates. Hence, on Earth, the function of bioluminescence could be slowly transformed from oxygen defense to its modern-day role in cross- and interspecific communication, predatory evasion and propagation. Although the explanation of the evolutionary origins of bioluminescence as an ancient oxygen defense does not seem to be valid for all forms of ecologically functional light, it accounts for a number of important features observed in extant luminous species: every bioluminescence without exception is depended on oxygen; the global influence of the GOE presented a universal selective pressure to all extant life and thereby led to convergent evolution; bioluminescence is predominantly found among marine organisms since luciferases started to turn into beneficial adaptations at a point in time when all life was still oceanic.

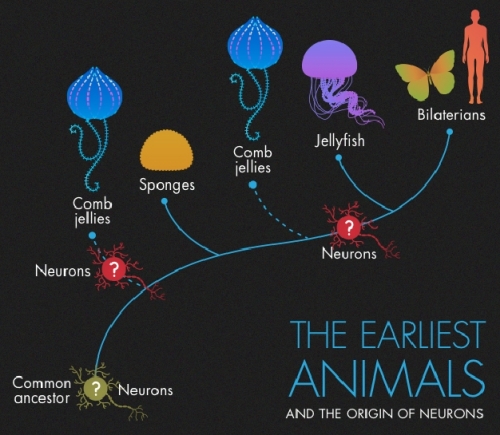

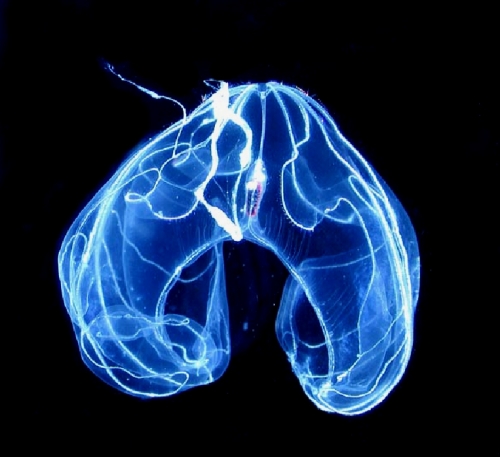

Recent genomic analysis of the comb jelly Mnemiopsis leidyi and Pleurobrachia bachei suggests the phylum of ctenophores, or comb jellies, (of which most members are bioluminescent) as the most basal group of metazoans [23]. Certain features in the genome structure of Mnemiopis are even implicating the co-evolution of emerging multicellular organization and the origin of coupled light-producing and detecting proteins. Thus, early vision systems could have possibly emerged in the deep sea for the first time or at least independently from pelagic organisms and their sunlit habitats. In fact, the newly released comb jelly genomes have caused a major controversy among evolutionary biologists because their primary branching off from the animal tree of life would either indicate a far more complex last common ancestor of all animals or convergent evolution of the most complex adaptation in nature: nervous systems. Both evolutionary scenarios pose serious problems to the neo-Darwinian doctrine. My current research is dealing with this fascinating evolutionary conundrum and I am currently working on comparative genomic analyses of the neurotransmitter complement of each respective animal phylum to discern whether neurons evolved only once or multiple times. In any case, yet another putative route to vision in sunless environments is presented by “infrared” vision as observed in the deep-sea shrimp Rimicaris exoculata. This species has evolved specialized cellular structures to detect the thermal signatures of hydrothermal vents. I hope to elaborate on these issues in a forthcoming paper that will specifically deal with the convergent emergence of bioluminescence on Europa. For now it suffices to clearly state that there are known adaptive routes among terrestrial biota enabling them to evolve visual systems in the absence of light. Consequently, on Europa, there might exist molecular pathways to not only produce bioluminescence but also to detect it. Ensuing co-evolution of both functions would obviously lead to a kind of amplifying “run-away” evolutionary process related to bioluminescent systems complexification. Amazingly, inside Europa’s abyssal ocean, light could have potentially been turned into a biological resource determining ecosystem dynamics beyond the organismal scale.

Image: The first sequenced comb jelly genomes are revolutionizing our understanding of the evolutionary emergence of animal complexity. Even complex nervous systems could be a product of convergent evolution. Image credit: Olena Shmahalo/Quanta magazine

What, then, can we learn from the evolutionary history of bioluminescence on Earth in regard to its hypothesized convergent emergence on Europa? First, oxygen is apparently indispensable for the evolution and maintenance of bioluminescence. In the ocean of Europa repeated oxygenation events could potentially occur due to the transport of oxidants from the surface. Depending on the exact mechanism of surface/ocean communication either a continuous and slow oxygenation or a more dramatic and periodically occurring influx of oxygen seem plausible. In any case, putative organisms on the rather hypoxic or anoxic seafloor that are pioneering in the exploration of the more oxygenated upper ocean layers would be in need of efficient means of oxygen detoxification. The convergent evolution of bioluminescence on Earth is a proof of the evolutionary robustness of luciferin/luciferase systems in achieving such adaptations in a global oceanic habitat. Secondly, rudimentary visual systems must have had already evolved (in multicellular organisms) as a pre-adaptation before the coopting of non-functional biological light, resulting from the activity of luciferin/luciferase systems acting as a means of oxidative protection, into ecologically relevant bioluminescence could begin.

CONCLUSIONS

The main idea behind this essay was to promote a new representation of evolutionary biology, one that is more encompassing than its predecessor – the neo-Darwinian synthesis. Based on the theoretical and practical work of many colleagues I termed this paradigm “Cosmic Convergent Evolution”. Like any scientific theory, CCE is a model, an attempt to understand the complexities of physical reality within the limitations of the human mind. Previous and current assumptions, hypotheses and mechanisms dealing with the origin, evolution and development of complex biological systems can be reassessed through the lens of CCE – evolutionary science always had an inherently retrograde character to it. However, in the grand vision of bioluminescent life forms on Europa I see hidden the predictive powers of CCE. If the combined body of scientific theorizing, experimental work and data streams acquired from decades of robotic space exploration hold true we have good reason to believe that a light is shining in the abyssal depths of Europa.

Fascinatingly, in a kind of self-referential meta-convergence, CCE does not only offer novel explanatory avenues for the emergence of biocomplexity. Technological applications, too, can be derived using its underlying assumption that top-down causation, convergent evolution and modularity are principles associated with biological as well as technological complex adaptive systems. Astrobiology is going to be the scientific and technological testing ground for CCE. The blue spectres of abyssal Europa are awaiting their discovery. Prometheus will be unbound.

Validation or falsification of CCE’s main tenets can come from disparate areas of research, be it the origin of life field, artificial intelligence, future space exploration, SETI studies, or animal cognition. Having experienced the wonders of convergent evolution myself by encountering the mesmerizing sentience of spotted and bottlenose dolphins in the Bahamas last year, my personal bet is on a dedicated organismal perspective. Research like that of Dr. Denise Herzing of the “Wild Dolphin Project” who is trying to crack the code of dolphin communication is highly successful in furthering our understanding and appreciation of “alien” intelligences. Vast amounts of information is still hidden in the genomes of countless unexplored species that inhabit our beautiful terrestrial ecosystems, many of them in our oceans. Future sequencing efforts of animal complexity and also metagenomic studies of microscopic life forms will revolutionize our understanding of genome evolution and the evolutionary process as a whole.

To summarize: Explaining the origin of life, pre-cellular evolution and multicellular biocomplexity in purely (neo)-Darwinian terms is like describing the quantum world with Newtonian physics. It is easy to see that “Universal Newtonism” is not able to unify modern-day physics; why should “Universal Darwinism” be able to do so when we consider the ever-increasing non-linear hyperspace of biological complexity [24]?

Personally, I never fully understood how Darwinism is purported to “integrate” all of the existing biological sciences. Among biologists it is widely acknowledged that The Origin of Species didn’t even satisfactorily explain its main subject, namely the process of speciation. As science progresses, we have to let go of much cherished models (i.e. the neo-Darwinian Synthesis) that do not suffice anymore to explain the phenomena we are theorizing and observing. Or to use a biological analogy: a kind of endosymbiosis takes place, where an advanced cell takes up a more limited-complexity unit, and eventually integrates it into its own cellular context where it will serve an important but subordinate function (given it is still viable within the new systemic whole; degeneration and disintegration is always an option too). This is simply how science works. Hard-core Darwinists (again, why are there no “Newtonists” around anymore?) shouldn’t fear some evil machinations of the creationists they so much love to vilify. They should rather watch out for the impact of overwhelming amounts of new biological data, as well as novel theoretical concepts, on their cherished notions of “Darwin-fits-it-all” evolution. In my opinion, orthodox understandings of evolutionary theory simply fail in explaining the observation of emerging higher-order systemic complexity throughout every major evolutionary transition. Any other approach apart from letting go of previous world-views will become dogma and ultimately earn its deserved spot in the dustbin of history. Again, Let us turn to the eternally echoing words of the eminent Carl R. Woese:

“Science is impelled by two main factors, technological advance and a guiding vision (overview). A properly balanced relationship between the two is key to the successful development of a science: without the proper technological advances the road ahead is blocked. Without a guiding vision there is no road ahead; …” [1]

Image: Terrestrial comb jelly: Bathocyroe fosteri. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.