Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Starshot Is a Success: Part I

The fortunes of Breakthrough Starshot have been the subject of so much discussion not only in comments in these pages but in backchannel emails that it is with relief that I turn to Jim Benford’s analysis of a project that has done significant work on interstellar travel and is still very much alive. Jim led the sail team for several of his eight years with Breakthrough Starshot and was with the project from the beginning. In this article and a second that will run in a few days, he explains how and why press coverage of the effort has been erroneous, and not always through the fault of writers working the story. Let’s now take a look at what Starshot has accomplished during its intensive Phase I.

by James Benford

“Make no mistake — interstellar travel will always be difficult and expensive, but it can no longer be considered impossible.” – Robert Forward

Breakthrough Starshot has not failed, nor has it been canceled. Phase I of the program achieved its stated objectives: to identify potential show-stoppers in beam-driven interstellar propulsion and determine whether credible solutions exist. That goal was met.

Recent media coverage, including a Scientific American cover article titled “Voyage to Nowhere,” misunderstands both the intent and the outcome of Phase I. The reality is that the project thus far has been successful. It was put “on hold, paused” in 2024 to restructure for the next phase and seek broader support. It has not been canceled, as some in the media are saying.

I contend that Starshot succeeded because the key Phase I objectives were met. Of course, extensive future effort in the later phases is needed to create a fully functional Starshot system, principally the beamer and sailcraft (referred in the project as “photon engine” and “lightsail”). The major issues have been found to have credible solutions. A great many Starshot-related papers have been published. Many address the crucial issues of sail materials and sail ‘beam-riding’, meaning staying on the beam while undergoing inevitable perturbations. There is a final report, but it has not yet been published.

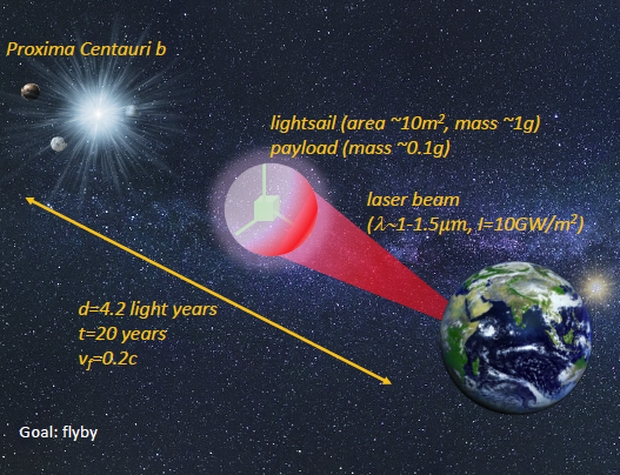

The principal issues for Starshot were 1) Can a phased array of lasers be constructed that is sufficiently coherent and directive as well as being affordable? 2) Can a sail material be made that will have high reflectivity, very low absorption, high emissivity and very low mass so as to be efficiently accelerated and not overheat? 3) Can a sail ride stably on the beam because of inherent restoring forces (without feedback, which is impossible over long ranges)? 4) Can data be sent back to Earth from the probe at sufficient data rates before the sail moves far beyond the target star?

In this first of two reports on the successes of the Starshot project, I discuss the shape of later phases in the effort, and distortions in the reporting on it. In the second report I will describe the major accomplishments of Phase I.

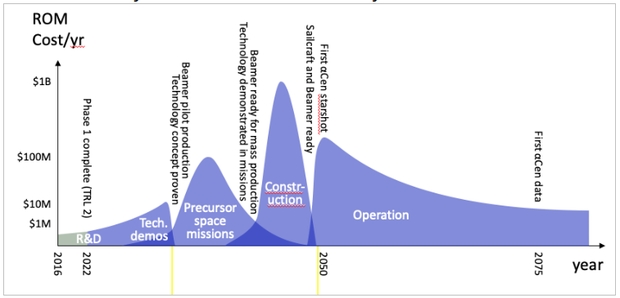

Starshot was not initiated to fully design, build and launch the first interstellar ‘lightsail’ (as they are called, referring to both the low mass and the near-visible frequency of the laser). The program path was divided into phases, as shown below. The first phase was to invest in high-risk, high-reward research that would de-risk the technology. Phase 1 was to find if there were any ‘show-stoppers’ and pave the way forward. It accomplished that.

High levels of research by Starshot retired most of these key issues for beam-driven sail systems, at least at the conceptual level. The results are at the TRL 2 level. Experiments are needed to verify the solutions for these major issues found in Phase 1.

In Phase II, a coalition of Caltech and other institutions would lead experimental technical demonstrations, and the first experiments in orbit. Then, with the technology concepts having been proven, it’s on to near-term missions shaking out various technologies while performing precursor missions, probably to the outer solar system. Much effort would be needed in systems engineering to enable such precursor missions.

The first phases of Starshot, the R&D program, are projected to cost $120M, which includes Phase 1, and concludes with solar system science missions in the medium-term. The large effort would then follow: construction of the Starshot System and finally, operation of the System and the first interstellar probe voyages.

Many requirements of the Starshot mission come together at the sail. Principal technical issues are the design of the beamer, material to be used and whether the beam and sail stay together, meaning stable beam-riding by the sail:

• Stability is influenced by sail shape, beam shape and the distribution of mass, such as payload, on the sail.

• Material properties, are its reflectivity, absorptivity and transmissivity, it’s tensile strength and its areal mass density.

• Deployment of the diaphanous sail, correctly oriented and including any initial spin, is of course a key requirement.

• The beamer interacts with the sail through its power distribution on the sail-causing differential stresses. This depends on duration of the acceleration, the transverse width of the beam, pointing error of the beam as well as its pointing jitter.

• Data return to Earth, interstellar communications, is perhaps the greatest challenge of all.

What Scientific American got wrong

Journalism is only the first draft of history, so flaws occur. Assessing a system as complex as Starshot is a challenge to a journalist with limited time. It would take years to read and absorb all the relevant literature and to mentally organize it into a reconciled and coherent understanding of the system as a whole.

The biased title – “Voyage To Nowhere” – of the piece in Scientific American, (which was chosen by the editors, not the author Sarah Scoles), may have been chosen to refer to the famous Bridge to Nowhere in Alaska and the Train to Nowhere in California. The Scientific American reporting is already being mistaken for a primary source by others, who are stating that Starshot has been “canceled”. This is an example of how media myths, once manufactured, propagate through journalistic copying.

The article fails to understand the Starshot project for a basic reason: The key people who did extensive work on the program were not available or not even known to the writer.

Because the principal workers from the Breakthrough Foundation and the leaders of Breakthrough Starshot, Pete Worden and Avi Loeb, were not interviewed, it seems the author did not know who the main contributors actually were. She relied instead on people she could easily reach. Few of them are major contributors to the program and most left the project early on or never actually participated in the project. A key participant who is not mentioned is Kevin Parkin [1, 2], who spent 8 years under contract, as did most of us who were in at the beginning or even before that. Others are Mason Peck (who is mentioned in the piece), Paul Mauskopf and Dave Messerschmitt. Unfortunately, the final report, which went through many iterations, has never been published publicly [3].

The recent policy of Breakthrough Starshot has been to have little contact with the media, so not to engage with Sarah Scoles at all didn’t help things: it left the door open for detractors to influence the narrative in her piece. Communication was a priority, with public outreach from and within Starshot during Phase 1. In research, communication enables cross-fertilization and prevents work duplication. The big gap now is a comprehensive publication that ties it all together. It could motivate researchers to continue or take up the project later if Phase II occurs.

The article also truncates the long history that led up to Starshot. Beam-driven propulsion concepts didn’t start in 2016! This was documented in my Photon Beam Propulsion Timeline, which appeared here at the start of Starshot in 2016. Media are not aware of how much has been done by the propulsion community over the last decades. Several areas of photon beam-driven sail system development, to include experiments demonstrating sail beam-driven flight [4, 5] and sail stability and dynamics, such as beam-driven spin of sails for stability [6, 7], have been reserched. The major innovation which caused the beginning of Starshot was the realization that going to much smaller sails and much higher accelerations reduces the cost of the overall system substantially.

The budget estimate given in the Scientific American article is clearly wrong. That only 4.5 million dollars could fund 8 years of steady work by many people is absurd. Thirty contracts were executed over 8 years. There were years of invitational meetings, a standing staff of advisors, subcommittees for specific topics; all of them further expenditures. And I count about 50 Starshot-related papers, some of which have been published since it was put on hold. I estimate that Breakthrough Starshot Phase 1 had a cost of 25 million dollars.

The way Forward

Phase II would lead to a firm experimental basis for the later phases in Figure 1. If Breakthrough decides to move on to Phase II, it must deal with the costs of interruption: institutional knowledge about the previous work, which is never fully captured in documentation, will need to be relearned, as the people who worked on Phase 1 have dispersed to other programs.

My second piece on Breakthrough Starshot, scheduled to run here next week, will describe the present state of the concept and the many advances achieved by Starshot in Phase I

Breakthrough Starshot was the most significant event in the history of beam propulsion, which clearly is the only way that probes can be sent to the stars in this century. And now the work goes on, the hope still lives, and the dream of beam-driven interstellar travel could be realized.

References

[1] “The Breakthrough Starshot Systems Model”, Kevin Parkin, Acta Astronautica 152, pp 370–384 (2018).

[2] “Starshot System Model” Kevin Parkin, Ch 3, in Claude Phipps, Editor, Laser Propulsion in Space: Fundamentals, Technology, and Future Missions, Elsevier (2024).

[3] Breakthrough Starshot Summary Report, September 2023, not published.

[4] “Microwave Beam-Driven Sail Flight Experiments”, James Benford, Gregory Benford, Keith Goodfellow, Raul Perez, Henry Harris, and Timothy Knowles, Proc. Space Technology and Applications International Forum, Space Exploration Technology Conf, AIP Conf. Proceedings 552, ISBN 1-56396-980-7STAIF, pg. 540, (2001).

[5] “Laser-Boosted Light Sail Experiments with the 150 kW LHMEL II CO2 Laser,” Leik Myrabo, Timothy Knowles, John Bagford and H. Harris, “High-Power Laser Ablation IV,” edited by Claude Phipps, Editor, Proc. Space Exploration Technology Conf., 4760 pp. 774-798 (2002).

[6] “Spin of Microwave Propelled Sails” Gregory Benford, Olga Goronostavea and James Benford, Beamed Energy Propulsion, AIP Conf. Proc. 664, pg. 313, A. Pakhomov, ed., (2003).

[7] “Experimental Tests of Beam-Riding Sail Dynamics”, James Benford, Gregory Benford, Olga Gornostaeva, Eusebio Garate, Michael Anderson, Alan Prichard, and Henry Harris, Proc. Space Technology and Applications International Forum (STAIF-2002), Space Exploration Technology Conf, AIP Conf. Proc. 608, ISBN 0-7354-0052-0, pg. 457, (2002).

The Language of Contact

How we think intersects with the language we think in. Consider the verb in classical Greek, a linguistic tool so complex that it surely allows shadings of thought that are the stuff of finely tuned philosophy. But are the thoughts in our texts genuinely capable of translation? Every now and then I get a glimpse of something integral that just can’t come across in another tongue.

Back in college (and this was a long time ago), I struggled with Greek from the age of Herodotus and then, in the following semester, moved into Homer, whose language was from maybe 300 years earlier. The Odyssey, our text for that semester, is loaded with repetitive phrases – called Homeric epithets – that are memory anchors for the performance of these epics, which were delivered before large crowds by rhapsōdoi (“song-stitchers”). I was never all that great in Homeric Greek, but I do remember getting so familiar with these ‘anchors’ that I was able now and then to read a sequence of five or six lines without a dictionary. But that was a rare event and I never got much better.

The experience convinced me that translation must always be no more than an approximation. A good translation conveys the thought, but the ineffable qualities of individual languages impose their own patina on the words. ‘Wine-dark sea’ is a lovely phrase in English, but when Homer spins it out in Greek, the phrase conjures different feelings within me, and I realize that the more we learn a language, the more we begin to think like its speakers.

My question then as now is how far can we take this? And moving into SETI realms, how much could we learn if we were actually to encounter alien speakers? Is there a possibility of so capturing their language that we could actually begin to think like them?

Let’s talk about Ted Chiang’s wonderful “Story of Your Life,” which was made (and somewhat changed) into the movie Arrival. Here linguist Louise Banks describes to her daughter her work on aliens called heptapods, seven-limbed creatures who are newly arrived on Earth, motives unknown, although they are communicating. Louise goes to work on Heptapod A and Heptapod B, the spoken and written language of the aliens respectively.

Image: A still from Denis Villeneuve’s 2016 film Arrival captures the mystery of deciphering an alien language.

Heptapod B is graphical, and it begins to become apparent that its symbols (semagrams), are put together into montages that represent complete thoughts or events. The aliens appear to experience time in a non-linear way. How can humans relate to that? Strikingly, immersion in this language has powerful effects on those learning it, as Louise explains in the story:

Before I learned how to think in Heptapod B, my memories grew like a column of cigarette ash, laid down by the infinitesimal sliver of combustion that was my consciousness, marking the sequential present. After I learned Heptapod B, new memories fell into place like gigantic blocks , each one measuring years in duration, and though they didn’t arrive in order or land continuously, they soon composed a period of five decades. It is the period during which I knew Heptapod B well enough to think in it, starting during my interviews with Flapper and Raspberry and ending with my death.

Flapper and Raspberry are the human team’s names for the two heptapods they’re dealing with, and we learn that Louise now has ‘memories’ that extend forward as well as back. Or as she goes on to explain:

Usually, Heptapod B affects just my memory; my consciousness crawls along as it did before, a glowing sliver crawling forward in time, the difference being that the ash of memory lies ahead as well as behind: there is no real combustion. But occasionally I have glimpses when Heptapod B truly reigns, and I experience past and future all at once; my consciousness becomes a half-century long ember burning outside time. I perceive – during those glimpses – that entire epoch as a simultaneity. It’s a period encompassing the rest of my life, and the entirety of yours.

The ‘yours’ refers to Louise’s daughter, and the heartbreak of the story is the vision forward. What would you do if you could indeed glimpse the future and see everything that awaited you, even the death of your only child? How would you behave where your consciousness is now, with that child merely a hoped for future being? How would such knowledge, soaked in the surety of the very language you thought in, affect the things you are going to do tomorrow?

A new paper out of Publications of the National Academy of Sciences has been the trigger for these reflections on Chiang’s tale, which I consider among the finest short stories in science fiction history. The paper, with Christian Bentz (Saarland University) as lead author, looks at 40,000 year old artifacts, all of them bearing sequences of geometric signs that had been engraved by early hunter-gatherers in the Aurignacian culture, the first Homo sapiens in central Europe. It was a time of migrations and shifting populations that would have included encounters with the existing Neanderthals.

These hunter-gatherers have left many traces, among which are these fragments that include several thousand geometric signs. What struck me was that these ancient artifacts demonstrate the same complexity as proto-cuneiform script from roughly 3000 BC. Working with Ewa Dutkiewicz (Museum of Prehistory and Early History of the National Museums, Berlin), Bentz notes objects like the ‘Adorant,’ an ivory plaque showing a creature that is half man, half lion. Found in the “Geißenklösterle,” a cave in the Achtal Valley in southern Germany, it’s marked by notches and rows of dots, in much the same way as a carved mammoth tusk from a cave in the Swabian Alb. The researchers see these markings as an early alternative to writing. Says Bentz:

“Our analyses allow us to demonstrate that the sequences of symbols have nothing in common with our modern writing system, which represents spoken languages and has a high information density. On the archaeological finds, however, we have symbols that repeat very frequently – cross, cross, cross, line, line, line – spoken languages do not exhibit these repetitive structures. But our results also show that the hunter-gatherers of the Paleolithic era developed a symbol system with a statistically comparable information density to the earliest proto-cuneiform tablets from ancient Mesopotamia – a full 40,000 years later. The sequences of symbols in proto-cuneiform are equally repetitive; the individual symbols are repeated with comparable frequency. The sequences are comparable in their complexity.”

Image: The so-called “Adorant” from the Geißenklösterle Cave is approximately 40,000 years old. It is a small ivory plaque with an anthropomorphic figure and several rows of notches and dots. The arrangement of these markings suggests a notational system, particularly the rows of dots on the back of the plaque. Credit: © Landesmuseum Württemberg / Hendrik Zwietasch, CC BY 4.0.

As the researchers comment, the result is surprising because you would think early cuneiform would be much closer in structure to modern systems of notation, but here we have, over a period of almost 40,000 years, evidence that such writing changed little since the Paleolithic. Says Bentz: “After that, around 5,000 years ago, a new system emerged relatively suddenly, representing spoken language—and there, of course, we find completely different statistical properties,”

The paper digs into the team’s computer analysis of the Paleolithic symbols, weighing the expression of information there against cuneiform and modern writing as well. It’s clear from the results that humans have been able to encode information into signs and symbols for many millennia, with writing as we know it being one growth from many earlier forms of encoding and sign systems.

We have no extraterrestrials to interrogate, but even with our own species, we have to ask what the experience of people who lived in the Stone Age was like. What were they trying to convey with their complex sequences of symbols? The authors assume they were as cognitively capable as modern humans and I see no reason to doubt that, but how we extract their thought from such symbols remains a mystery to be resolved by future work in archaeology and linguistics.

And I wonder whether Ted Chiang’s story doesn’t tell us something about the experience of going beyond translation into total immersion in an unknown text. How does that change us? Acquiring a new language, even a modern one, subtly changes thought, and I’m also reminded of my mother’s Alzheimer’s, which somehow left her able to acquire Spanish phrases even as she lost the ability to speak in English. I always read to her, and when I tried to teach her some basic Spanish, the experiment was startlingly successful. That attempt left me wondering what parts of the human brain may be affected by full immersion in the language of any future extraterrestrial who may become known to us.

Ludwig Wittgenstein argued that words only map a deeper reality, saying “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” Beyond this map, how do we proceed? Perhaps one day SETI will succeed and we will explore that terrain.

The paper is Bentz et al., “Humans 40,000 y ago developed a system of conventional signs,” Publications of the National Academy of Sciences 123 (9) e2520385123. 23 February 2026. Full text. For more on this work, see Bentz and Dutkiewicz’ YouTube video: https://www.youtube.com/@StoneAgeSigns. Thanks to my ever reliable friend Antonio Tavani for sending me information about this paper.

Propulsion Options for the Solar Gravitational Lens Mission

A mission to the Sun’s gravity focus – or more precisely, the focal ‘line’ we might begin to use at around 650 AU – is never far from my mind. Any interstellar mission we might launch within the next thirty years or so (think Breakthrough Starshot, about which more next week) will essentially be shooting blind. We have little idea what to expect at Proxima Centauri b, if that is our (logical) target. But a mission to the solar gravity focus (SGL) would give us a chance to examine any prospective target at close hand.

Indeed, so powerful are the effects if we can exploit this opportunity that we should be able to see continents, weather patterns, oceans and more if we can disentangle the Einstein Ring that the planet’s image forms as shaped by general relativity. We’ve discussed the phenomenon many a time: The Sun’s gravitational well so shapes the image of what is directly behind it as seen from the SGL so as to produce stupendous magnification, the image served up as a ‘ring’ around the Sun in the same way that astronomers now see some distant galaxies as rings around closer galaxies.

Image:The Einstein Ring and how we could sample it. By looking at different slices of the Einstein ring, enough information could be acquired for a computer deconvolution to reconstruct the planet. Credit: Geoffrey Landis (NASA GRC).

Within that ring there is bountiful information. Not only would we have an image we could reconstruct, but we also would have multipixel spectroscopy, allowing us to identify elements through the signature of light from the planet aand to map these properties in more than one dimension. So fecund is the information in the Einstein ring that we could detect all this with a spacecraft telescope no more than a meter or so in diameter. And because the SGL focal line extends to infinity, we can keep taking observations as we move outward from 650 AU to perhaps 900 AU.

Now comes JPL scientist Slava Turyshev with a trade study – an analysis made to evaluate and select the best propulsion technique to make a flight to the SGL possible within a rational timeframe, here seen as roughly thirty years. That seems like a lot, but bear in mind that even our far-flung Voyagers have yet to reach a distance that’s even halfway to the SGL region. Remember, too, that once we find a way to propel a craft to the SGL, we have to choose a trajectory so precise that our target will be exactly opposite the Sun from the spacecraft. In this business, alignment is everything.

Each new Turyshev paper into SGL territory reminds us that this work has been taken into Phase III status at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, funded by NASA’s Institute for Advanced Concepts. The potential showstoppers of an SGL mission are daunting, and have been examined in papers that examine everything from sail design and ‘sundiver’ trajectories to deconvolution of an SGL image. Perhaps most futuristic has been the Turyshev team’s discussion of self-assembly of a payload divided into small packages into the completed observational equipment enroute. Previous Centauri Dreams articles such as Solar Gravitational Lens: Sailcraft and Inflight Assembly or Good News for a Gravitational Focus Mission may be helpful, though the pace of stories on the SGL has been accelerating, and for the complete sequence I suggest a search in the archives.

All this is bringing me around to the scope of the propulsion problem. In addition to the need for precise positioning within the SGL focal line, the spacecraft must be able to move laterally within the image, which is of considerable size. One recent calculation found that an Earth-sized planet orbiting Epsilon Eridani (10 light years away) would project an image 12.5 kilometers in diameter at 630 AU from the Sun. One envisions multiple spacecraft taking pixel samples at various locations within the image plane. The image must then be produced by integrating these samples. This is ‘deconvolution,’ turning the Einstein ring into a coherent image free of ‘noise.’

As Geoffrey Landis, who made this calculation, points out: The image is far larger than the spacecraft we send. Landis (NASA GRC) also notes that a one-meter telescope at the SGL collects the same amount of light as a telescope of 80 meters without the gravitational lens. So we definitely want to do this, but to make it happen, the spacecraft will need propulsion and power. All this has a bearing on payload, for in an environment where solar panels are not an option, we need a radioisotope or fission power source.

Back to the Turyshev paper. Propulsion emerges as perhaps the mission’s most significant challenge, although one that the author thinks can be met. Here we run into what I call the ‘generation clock,’ which is the desire to keep mission outcomes within the lifetime of researchers who launched the project. Twenty to thirty years in cruise is often mentioned in connection with the SGL mission, meaning we need the ability to reach 650 AU with our spacecraft within that timeframe. A daunting task, for it involves reaching 154 kilometers per second. On outbound trajectories we’ve yet to exceed Voyager’s 17.1 km/sec, highlighting the magnitude of the problem.

Image: JPL’s Slava Turyshev.

We can’t solve it with chemical rockets, not even with gravity assist strategies, but solar sails coupled with an Oberth maneuver loom large as a potential solution. Advances in materials science and the success of missions like the Parker Solar Probe remind us of the potential here, offering the option of deploying a sail in a tight perihelion pass to achieve a massive boost. To manage 650 AU in 20 years means we will need 32.5 AU per year. But if we can work with a perihelion pass at 0.05 AU (7,500,000 km), we can achieve that speed, and the Parker probe has already proven we know how to do this. Finding the metamaterials to make a sail survive such a passage is an ongoing task.

The paper sums the issue up:

Recent “extreme solar sailing” studies emphasize that very fast transits are achievable in principle only by combining ultra-low total areal density with very deep perihelia (a few solar radii), which moves the feasibility question from trajectory mechanics to coupled materials, thermal, and large-area deployment qualification. For example, [Davoyan et al., 2021] analyzed extreme-proximity solar sailing (≲ 5 R⊙) and discussed candidate metamaterial sail approaches together with the associated environmental and system challenges at these perihelia. These results reinforce the conclusion here: sub-20 yr sail-only access is not ruled out by physics, but it lives in a tightly coupled materials+structures+thermal qualification regime at mission scale.

So we have a lot to learn to make this happen. The paper notes that as we move from current sail readiness to what we will need for the SGL mission, we go from sails that are in the 10-meter class up to sails as much as 300 meters in diameter, while still needing to keep our sail material astonishingly thin and capable of surviving the perihelion temperatures. Operating at deep perihelia with metamaterials is a subject still very low on the TRL level, meaning technical readiness to produce and fly such a sail is nowhere near where it needs to be if we are to launch in the 2035-2040 window hoped for by mission planners. If we can launch multiple sails, we can consider self-assembly of the larger payload in transit, also at a very low TRL

Importantly, this maturity gap is not a physics limit: it is a program-and-demonstration limit. A focused late2020s/early-2030s development that couples (i) large-area deployment validation, (ii) deep-perihelion optical-property stability tests, and (iii) integrated areal-density demonstrations at the 104–105 m2 scale could credibly raise the SGL-class sail system TRL into the mission-start window, particularly for the 25–40 yr-class access regime.

Image: Sailcraft example trajectory toward the Solar Gravity Lens. Taken from an earlier report by Turyshev et al.

Nuclear electric propulsion (NEP) offers certain advantages over solar sails, including the fission reactor that powers its thrusters, for as mentioned, solar power at these distances is not practical. Turyshev’s calculations make the needed comparison, yielding a mission that can reach 650 AU in 27 years, putting it in range of what the sail strategy can deliver. Using propellant remaining in the craft upon arrival at the SGL, our spacecraft can now manage station-keeping and trajectory changes necessary to collect the needed pixels of our exoplanet image. In terms of operations, then, as well as payload capability, NEP stands out. Note that here again we have thermal issues, for the NEP-powered craft will need their own close perihelion pass to boost velocity. Turyshev points out that NEP will also demand large, deployable radiators to allow the escape of waste heat.

Nuclear thermal propulsion (NTP) now comes into the discussion, as the author considers potential hybrid missions. In NTP, liquid hydrogen is heated by the reactor core to produce thrust through the exhaust nozzle. Capable of high specific impulse, this method is treated here as “a high-thrust injection stage,” one that could be used during an Oberth maneuver to increase the velocity of an NEP-equipped spacecraft. The nuclear issues persist: We need safety analyses and ground testing facilities for the reactor, radiological handling protocols, and additional flight approval processes.

The three propulsion options play against each other in interesting ways. Sails avoid the problem of flight approval for nuclear materials as well as necessary infrastructure for ground testing. But materials and deployment issues still exist for these ultra-thin sails. An NEP engine that offers wider use beyond the SGL mission could lower incremental costs. And what if we tinker with mission duration? The fact remains that regardless of the choice of propulsion, we still have to operate in an environment that requires radioisotope or fission power, with all the implications for payload overhead that entails.

Programmatically, a credible 2035–2040 start requires aligning architecture choice with what can be demonstrated by the early 2030s. If minimum TOF [time of flight] is the primary requirement, solar sailing (with an explicit deep-perihelion materials and deployment qualification program) remains the most schedule-aligned approach. If delivered capability and operational robustness at the SGL dominate, NEP is uniquely attractive, but a 2035–2040 launch that depends on NEP for transportation must be preceded by an integrated stage demonstration that retires system-level coupling risks (thermal, EMI/EMC [Electromagnetic Interference / Electromagnetic Compatibility], plume, autonomy, and nuclear approval). In either case, SGL transportation should be treated as flagship-class in development complexity because the critical path runs through integrated demonstrations rather than through single-component maturity.

This is how missions get designed, and you can see how involved the process becomes long before actual hardware is even built. My belief is that the question of the generation clock is fading, for in dealing with issues like the SGL, we’re forced to contemplate scenarios in which those who plan the mission may not see its completion (although I hope Slava Turyshev is very much an exception!) In sending missions beyond the Solar System, we create gifts of data to future generations, who may well use what the SGL finds to plan missions much further afield, perhaps all the way to Proxima Centauri b.

The paper is Turyshev, “Propulsion Trades for a 2035-2040 Solar Gravitational Lens Mission,” currently available as a preprint. For more on acquisition of the lensed image, see Geoffrey Landis’ extremely useful slide presentation.

A Relativistic Explanation for the Dearth of Circumbinary Planets

Planets orbiting two stars have been found, but not all that many of them. We’re talking here about a planet that orbits both stars of a close binary system, and thus far, although we’ve confirmed over 6,000 exoplanets, we’ve only found 14 of them in this configuration. Circumbinary planets are odd enough to make us question what it is we don’t know about their formation and evolution that accounts for this. Now a paper from researchers at UC-Berkeley and the American University of Beirut probes a mechanism Einstein would love.

At play here are relativistic effects, having to do with the fact that, as Einstein explained, intense gravitational fields have detectable effects upon the stars’ orbits. This is hardly news, as it was the precession of Mercury in the sky that General Relativity first predicted. The planet’s orbit could be seen to precess (shift) by 43 arcseconds per century more than was expected by Newtonian mechanics. Einstein showed in 1915 that spacetime curvature could account for this, and calculated the exact 43 arcsecond shift astronomers observed.

What we see in close binary systems is that if we diagram the elliptical orbit usually found in such systems, the line connecting the closest approach (periastron) and farthest point in the orbit (apoapsis) gradually rotates. The term for this is apsidal precession. This precession – rotation of the orbital axis – is coupled with tidal interactions between the two stars, which make their own contribution to the effect. Close binary orbits, then, should be seen as shifting over time, partly as a consequence of General Relativity.

The researchers calculate that as the precession rate of the stars increases, that of a planet orbiting both stars slows. The planet’s perturbation can be accounted for by Newtonian mechanics, and its lessening precession is the result of tidal effects gradually shrinking the orbit of the two binary stars. But note this: When the two precession rates match, or come into resonance, the planet experiences serious consequences. Mohammad Farhat, (UC Berkeley) and first author of the paper, phrases the matter this way:

“Two things can happen: Either the planet gets very, very close to the binary, suffering tidal disruption or being engulfed by one of the stars, or its orbit gets significantly perturbed by the binary to be eventually ejected from the system. In both cases, you get rid of the planet.”

Image: An artist’s depiction of a planet orbiting a binary star. Here, the stars have radically different masses and as they orbit one another, they tug the planet in a way that makes the planet’s orbit slowly rotate or precess. Based on dynamic modeling, general relativistic effects make the orbit of the binary also precess. Over time, the precession rates change and, if they sync, the planet’s orbit becomes wildly eccentric. This causes the planet to either get expelled from the system or engulfed by one of the stars. Credit: NASA GSFC.

Does this mean that circumbinary planets are rare, or does it imply that most of them are probably in outer orbits and hard to find by our current methods? Ejection from the system seems the most likely outcome, but who knows? The researchers make three points about this. Quoting the paper:

(i) Systems that result in tight binaries (period ≤ 7.45 days, that of Kepler-47) via orbital decay are more likely than not deprived of a companion planet: the resonance-driven growth of the planet’s eccentricity typically drives it into the throes of its host’s driven instabilities, leading to ejection or engulfment by that host.

(ii) Planetary survivors of the sweeping resonance mostly reside far from their host and are therefore less likely to have their transits detected. Should eccentric survivors nevertheless be detected, they are expected to bear the signature of resonant capture into apse alignment with the binary.

(iii) The process appears robust to the modeling of the initial binary separation, with three out of four planets around tight binaries experiencing disruption…

What we wind up with here is that circumbinary planets are hard to find, but the greatest scarcity is going to be circumbinaries around binary systems whose orbital period is seven days or less. The researchers note that 12 of the 14 known circumbinary planets are close to but not within what they describe as the ‘instability zone,’ where these effects would be the strongest. Indeed, the combination of general relativistic effects and tidal interactions is calculated here to disrupt planets around tight binaries about 80 percent of the time. Most of the planets thus disrupted would most likely be destroyed in the process.

The paper is Farhat & Touma, “Capture into Apsidal Resonance and the Decimation of Planets around Inspiraling Binaries,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 995, No. 1 (8 December 2025), L23. Full text.

A New Tool for Exoplanet Detection and Characterization

It’s been apparent for a long time that far more astronomical data exist than anyone has had time to examine thoroughly. That’s a reassuring thought, given the uses to which we can put these resources. Ponder such programs as Digital Access to a Sky Century at Harvard (DASCH), which draws on a trove of over half a million glass photographic plates dating back to 1885. The First and Second Palomar Sky Surveys (POSS-1 and POSS-2) go back to 1949 and are now part of the Digitized Sky Survey, which has digitized the original photographic plates. The Zwicky Transient Facility, incidentally, uses the same 48-inch Samuel Oschin Schmidt Telescope at Palomar that produced the original DSS data.

There is, in short, plenty of archival material to work with for whatever purposes astronomers want to pursue. You may remember our lengthy discussion of the unusual star KIC 8462852 (Boyajian’s Star), in which data from DASCH were used to explore the dimming of the star over time, the source of considerable controversy (see, for example, Bradley Schaefer: Further Thoughts on the Dimming of KIC 8462852 and the numerous posts surrounding the KIC 8462852 phenomenon in these pages). Archival data give us a window by which we can explore a celestial observation through time, or even look for evidence of technosignatures close to home (see ‘Lurker’ Probes & Disappearing Stars).

But now we have an entirely new class of archival data to mine and apply to the study of exoplanets. A just published paper discusses how previously undetectable data about stars and exoplanets can be found within the archives of radio astronomy surveys. The analysis method has the name Multiplexed Interferometric Radio Spectroscopy (RIMS), and it’s intriguing to learn that it may be able to detect an exoplanet’s interactions with its star, and even to run its analyses on large numbers of stars within the radio telescope’s field of view.

We are in the early stages of this work, with the first detections now needing to be further analyzed and subsequent observations made to confirm the method, so I don’t want to minimize the need for continuing study. But if things pan out, we may have added a new method to our toolkit for exoplanet detection.

The signature finding here is that the huge volumes of data accumulated by radio telescopes worldwide, so vital in the study of cosmology through the analysis of galaxies and black holes, can also track variable activity of numerous stars that are within the field of view of each of these observations. What the authors are unveiling here is the ability to perform a simultaneous survey across hundreds or potentially thousands of stars. Cyril Tasse, lead author of the paper in Nature Astronomy, is an astronomer at the Paris Observatory. Tasse explains the range that RIMS can deploy:

“RIMS exploits every second of observation, in hundreds of directions across the sky. What we used to do source by source, we can now do simultaneously. Without this method, it would have taken nearly 180 years of targeted observations to reach the same detection level.”

The researchers have examined 1.4 years of data collected at the European LOFAR (Low Frequency Array) radio telescope at 150 MHz. Here low frequency wavelengths from 10 to 240 MHz are probed by a huge array of small, fixed antennas, with locations spread across Europe, their data digitized and combined using a supercomputer at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. Out of this data windfall the RIMS team has been able to generate some 200,000 spectra from stars, some of them hosting exoplanets. While a stellar explanation is possible for star-planet interactions, this form of analysis, say the authors, “demonstrate[s] the potential of the method for studying stellar and star–planet interactions with the Square Kilometre Array.” LOFAR can be considered a precursor to the low-frequency component of the SKA.

Here we drill down to the planetary system level, for among the violent stellar events that RIMS can track (think coronal mass ejections, for example), the researchers have traced signals that produce what we would expect to find with magnetic interactions between planet and star. Closer to home, we’ve investigated the auroral activity on Jupiter, but now we may be tracing similar phenomena on planets we have yet to detect through any other means.

Image: Artistic illustration of the magnetic interaction between a red dwarf star such as GJ 687, and its exoplanet. Credit: Danielle Futselaar/Artsource.nl.

Let’s focus for a moment on the importance of magnetic fields when it comes to making sense of stellar systems other than our own. The interior composition of planets – their internal dynamo – can be explored with a proper understanding of their magnetosphere, which also unlocks information about the parent star. That sounds highly theoretical, but on the practical plane it points toward a signal we want to acquire from an exoplanetary system in order to understand the environments present on orbiting worlds. And don’t forget how critical a magnetic field is in terms of habitability, for fragile atmospheres must be shielded from stellar winds so as to be preserved.

At the core of the new detection method is cyclotron maser instability(CMI), which is the basic process that produces the intense radio emissions we see from planets like Jupiter. CMI is an instability in a plasma, where electrons moving in a magnetic field produce coherent electromagnetic radiation. Here is a link to Juno observations of these phenomena around Jupiter.

Detecting such emissions, RIMS can point to the presence of a planet in a stellar system. Working with radio observations, we can move beyond modeling to sample actual field strengths, which is why radio emissions (not SETI!) from exoplanets have been sought for decades now. Finding a way to produce interferometric data sufficient to paint a star-planet signature is thus a priority.

Exoplanetary aurorae would indicate the existence of magnetospheres, and that’s no small result. And we may be making such a detection around a star some 14.8 light years away, says co-author Jake Turner (Cornell University):

“Our results indicate that some of the radio bursts, most notably from the exoplanetary system GJ 687, are consistent with a close-in planet disturbing the stellar magnetic field and driving intense radio emission. Specifically, our modeling shows that these radio bursts allow us to place limits on the magnetic field of the Neptune-sized planet GJ 687 b, offering a rare indirect way to study magnetic fields on worlds beyond our Solar System.”

There are also implications for the search for life elsewhere in the cosmos. Turner adds:

“Exoplanets with and without a magnetic field form, behave and evolve very differently. Therefore, there is great need to understand whether planets possess such fields. Most importantly, magnetic fields may also be important for sustaining the habitability of exoplanets, such as is the case for Earth,”

Using low-frequency radio astronomy, then, we turn a telescope array into a magnetosphere detector. Researchers have also applied the MIMS technique to the French low frequency array NenuFAR, located at the Nançay Radio Observatory south of Paris, detecting a burst from the exoplanetary system HD 189733 that was described recently in Astronomy & Astrophysics. As with another possible burst from Tau Boötes, the team is in the midst of making follow-up observations to confirm that both signals came from a star-planet interaction. If the method is proven successful, such interactions point to a new astronomical tool.

The paper is Tasse et al., “The detection of circularly polarized radio bursts from stellar and exoplanetary systems,” Nature Astronomy 27 January 2026 (abstract). The earlier paper is Zhang et al., “A circularly polarized low-frequency radio burst from the exoplanetary system HD 189733,” Astronomy & Astrophysics Vol. 700, A140 (August 2025). Full text.

Holography: Shaping a Diffractive Sail

One result of the Breakthrough Starshot effort has been an intense examination of sail stability under a laser beam. The issue is critical, for a small sail under a powerful beam for only a few minutes must not only survive the acceleration but follow a precise trajectory. As Greg Matloff explains in the essay below, holography used in conjunction with a diffractive sail (one that diffracts light waves through optical structures like microscopic gratings or metamaterials) can allow a flat sail to operate like a curved or even round one. I’ll have more on this in terms of the numerous sail papers that Starshot has spawned soon. For today, Greg explains how what had begun as an attempt to harness holography for messaging on a deep space probe can also become a key to flight operations. The Alpha Cubesat now in orbit is an early test of these concepts. The author of The Starflight Handbook among many other books (volumes whose pages have often been graced by the artwork of the gifted C Bangs), Greg has been inspiring this writer since 1989.

by Greg Matloff

The study of diffractive photon sails likely begins in 1999 during the first year of my tenure as a NASA Summer Faculty Fellow. I was attending an IAA symposium in Aosta, Italy where my wife C Bangs curated a concurrent art show. The title of the show , which included work by about thirty artists, was “Messages from Earth”. At the show’s opening, C was approached by visionary physicist Robert Forward who informed her that the best technology to affix a message plaque to an interstellar photon sail was holography. A few weeks later, back in Huntsville AL, Bob suggested to NASA manager Les Johnson that he fund her to create a prototype holographic interstellar message plaque.

It is likely that Bob encouraged this art project as an engineering demonstration. He was aware that photon sails do not last long in Low Earth Orbit because the optimum sail aspect angle to increase orbital energy is also the worst angle to increase atmospheric drag. He had experimented with the concept of a two-sail photon sail and correctly assumed that from a dynamic point of view such a sail would fail. A thin-film hologram of an appropriate optical device could redirect solar radiation pressure accurately without increasing drag.

Our efforts resulted in the creation of a prototype holographic interstellar message plaque that is currently at NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. It was displayed to NASA staff during the summer of 2001 and has been described in a NASA report and elsewhere [1].

I thought little about holography until 2016, when I was asked by Harvard’s Avi Loeb to participate in Breakthrough Starshot as a member of the Scientific Advisory Committee. This technology development project examined the possibility of inserting nano-spacecraft into the beam of a high energy laser array located on a terrestrial mountain top. The highly reflective photon sail affixed to the tiny payload could in theory be accelerated to 20% of the speed of light.

One of the major issues was sail stability during the 5-6 minutes in a laser beam moving with Earth’s rotation. Work by Greg and Jim Benford, Avi Loeb and Zac Manchester (Carnegie Mellon University) indicated that a curved sail was necessary. to compensate for beam motion. But a curved thin sail would collapse immediately during the enormous acceleration load.

Some researchers realized that a diffractive sail that could simulate a curved surface might be necessary. Grover Swartzlander of Rochester Institute of Technology published on the topic [2].

Martina Mongrovius, then Creative Director of the NYC HoloCenter, suggested to C that one approach to incorporating an image of an appropriate diffractive optical device in the physically flat sail was holography; this was later confirmed by Swartzlander. Avi Loeb arranged for C to attend the 2017 Breakthrough meeting and demonstrate our version of the prototype holographic message plaque.

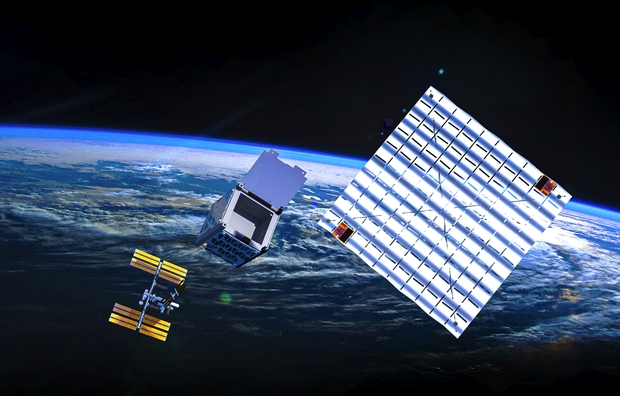

A Breakthrough Advisor present at the demonstration was Cornell professor and former NASA chief technologist Mason Peck. Mason invited C to create, with Martina’s aid, five holograms to be affixed to Cornell’s Alpha CubeSat, a student-coordinated project to serve as a test bed for several Starshot technologies.

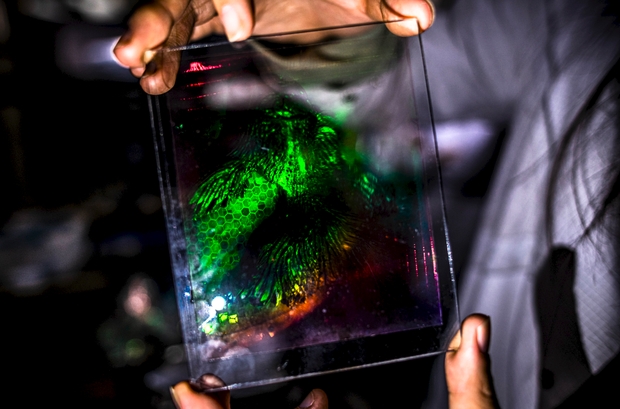

Image: Fish Hologram (Sculpture by C Bangs, exposure by Martina Mrongovius). A holographic plaque could carry an interstellar message. But could holography also be used to simulate the optimal sail surface on a flat sail?

During the next eight years, about 100 Cornell aerospace engineering students participated in the project. Doctoral student Joshua Umansky-Castro, who has now earned his Ph.D. was the major coordinator.

In 2023, there was an exhibition aboard the NYC museum ship Intrepid (a World War II era aircraft carrier) presenting the scientific and artistic work of the Alpha CubeSat team. Alpha was launched in September of 2025 as part of a ferry mission to the ISS. The cubesat was deployed in Dec. 2025.

All goals of the effort have been successfully achieved. The tiny chipsats continue to communicate with Earth. The demonstration sail deployed as planned from the CubeSat. A post-deployment glint photographed from the ISS indicates that the holograms perform in space as expected, increasing the Technological Readiness of in-space holograms and diffraction sailing.

In May 2026 a workshop on Lagrange Sunshades to alleviate global warning is scheduled to take place in Nottingham. The best sunshade concepts suggested to date are reflective sails. Two issues with reflective sail sunshades are apparent. One is the meta-stability of L1, which requires active control to maintain the sunshade on station. A related issue is that the solar radiation momentum flux moves the effective Lagrange point farther from the Earth, requiring a larger sunshade. At the Nottingham Workshop. C and I will collaborate with Grover Swartzlander to demonstrate how a holographic/diffractive sunshade surface alleviates these issues.

References

1.G. L. Matloff, G. Vulpetti, C. Bangs and R. Haggerty, “The Interstellar Probe (ISP): Pre-Perihelion Trajectories and Application of Holography”, NASA/CR-2002-211730, NASA Marshal Spaceflight Center, Huntsville, AL (June, 2002). Also see G. L. Matloff, Deep-Space Probes: To the Outer Solar System and Beyond, 2nd. ed., Springer/Praxis, Chichester, UK (2005).

2.G. A. Swartzlander, Jr., “Radiation Pressure on a Diffractive Sailcraft”, arXiv: 1703.02940.