We’re getting close on New Horizons data, all of which should be downlinked as of this weekend. Although that’s a welcome marker, it hardly means the end of news from the doughty spacecraft. For one thing, we have years of analysis ahead of us as we bring the abundant data from the spacecraft’s instrument packages into focus. For another, we’re still in business out there in the Kuiper Belt, heading for that interesting object 2014 MU69.

Who knows what will turn up at the latter, given our propensity to be surprised at every turn in interplanetary exploration, from Triton’s volcanic plains to fabulously fractured Miranda. And, of course, Pluto and Charon themselves, which turned out to be so interesting that Alan Stern, principal investigator for New Horizons, is already talking about future missions there.

But back to 2014 MU69, which has continued to be the subject of Hubble observations even as New Horizons homes in on the object. As this news release from the mission points out, MU69 is the smallest KBO ever to have its color measured, a reddish hue that confirms its identity as part of the ‘cold classical’ region of the Kuiper Belt. These are objects with low orbital eccentricity and inclination that are not in orbital resonance with Neptune. Reddish-brown tholins formed by solar radiation interacting with simple organic compounds are common here.

“The reddish color tells us the type of Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69 is,” says Amanda Zangari, a New Horizons post-doctoral researcher from Southwest Research Institute. “The data confirms that on New Year’s Day 2019, New Horizons will be looking at one of the ancient building blocks of the planets.”

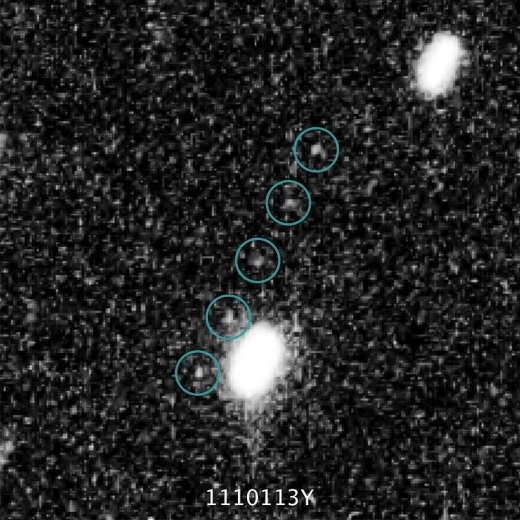

Image: 2014 MU69 travels diagonally across a dense field of stars and noise in the background. Credit: NASA, ESA, SwRI, JHU/APL, and the New Horizons KBO Search Team.

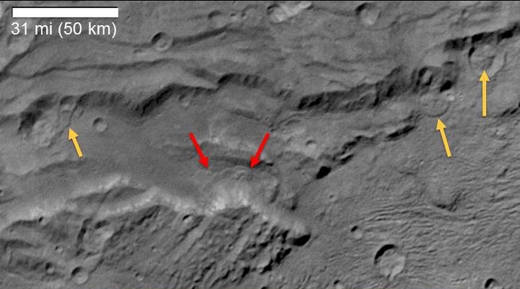

New Horizons has now covered a third of its distance from Pluto to MU69, with the target approximately a billion kilometers away. The analysis of New Horizons data, meanwhile, is turning up interesting things on Charon, where we find landslides, a feature that has not yet been spotted on Pluto’s surface, although we’ve found them on worlds as diverse as Mars and Iapetus. The Charon landslides are the farthest ever observed from the Sun.

Image: Scientists from NASA’s New Horizons mission have spotted signs of long run-out landslides on Pluto’s largest moon, Charon. This image of Charon’s informally named Serenity Chasma was taken by New Horizons’ Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) on July 14, 2015, from a distance of 78,717 kilometers. Arrows mark indications of landslide activity. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

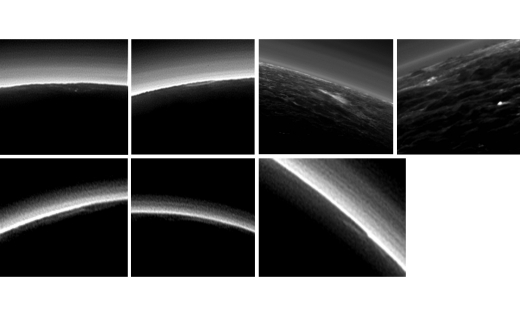

Likewise, we learn that while Pluto’s atmosphere is hazy but largely cloud-free, a handful of possible clouds have turned up in New Horizons imagery. That would point to an atmosphere still more complex than expected. And the variations in surface brightness on Pluto itself are telling. Some of these regions, particularly in Pluto’s now famous heart-shaped region, are among the most reflective in the Solar System. This has implications for what may be occurring on another deep space object, says Bonnie Buratti (JPL), a co-investigator on the New Horizons science team:

“That brightness indicates surface activity. Because we see a pattern of high surface reflectivity equating to activity, we can infer that the dwarf planet Eris, which is known to be highly reflective, is also likely to be active.”

Image: Pluto’s present, hazy atmosphere is almost entirely free of clouds, though scientists from NASA’s New Horizons mission have identified some cloud candidates after examining images taken by the New Horizons Long Range Reconnaissance Imager and Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera, during the spacecraft’s July 2015 flight through the Pluto system. All are low-lying, isolated small features-no broad cloud decks or fields – and while none of the features can be confirmed with stereo imaging, scientists say they are suggestive of possible, rare condensation clouds. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

We’re a long way from through with New Horizons, which should make its flyby of 2014 MU69 on January 1, 2019 after the series of four course changes that adjusted its trajectory. We may have other outer system news to discuss as the joint meeting of the American Astronomical Society Division for Planetary Sciences and European Planetary Science Congress in Pasadena continues this week. But for now, I particularly like Alan Stern’s words:

“We’re excited about the exploration ahead for New Horizons, and also about what we are still discovering from Pluto flyby data. Now, with our spacecraft transmitting the last of its data from last summer’s flight through the Pluto system, we know that the next great exploration of Pluto will require another mission to be sent there.”

DPS/EPSC update: 2007 OR10 has a moon!

Posted by Emily Lakdawalla on 2016/10/19 11:46 CDT

The third-largest object known beyond Neptune, 2007 OR10, has a moon. The discovery was reported in a poster by Gábor Marton, Csaba Kiss, and Thomas Mueller at the joint meeting of the European Planetary Science Congress and the Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society (DPS/EPSC) on Monday.

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2016/10190940-dpsepsc-update-2007-or10.html

If the cloud candidates on Pluto aren’t actually clouds, we will have an even bigger mystery on our hands.

Nah… they’re just exhaust-gases from the fleet of ships enforcing the zoo-hypothesis ;)

One would think they would have the decency to hide themselves a little better. :-)

A little more seriously, if they are not clouds, how about some kind of active ice volcanoes, geysers or leaks? Wright Mons has already been identified as a possible ice volcano, so it would not be completely out of the question.

Keep those surprises coming!

10/19/2016

Curious Tilt of the Sun Traced to Undiscovered Planet

Planet Nine—the undiscovered planet at the edge of the Solar System that was predicted by the work of Caltech’s Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown in January 2016—appears to be responsible for the unusual tilt of the sun, according to a new study.

The large and distant planet may be adding a wobble to the solar system, giving the appearance that the sun is tilted slightly.

“Because Planet Nine is so massive and has an orbit tilted compared to the other planets, the solar system has no choice but to slowly twist out of alignment,” says Elizabeth Bailey, a graduate student at Caltech and lead author of a study announcing the discovery.

Full article here:

http://www.caltech.edu/news/curious-tilt-sun-traced-undiscovered-planet-52710

Has anyone checked to see if New Horizons is being affected in its flight path by Planet Nine?

I wonder if New Horizons will someday catch a glimpse of Planet Nine.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/10/161019173023.htm

Any evidence for Tholins on Pluto?

Plenty, the UV at Pluto should be similar to what we receive on earth less the oxygen degradation.

Astronomy Magazine announces first-ever Pluto globe

Posted by David Eicher on Monday, October 17, 2016

Waukesha, Wis. – Kalmbach Publishing Co., publisher of Astronomy magazine and Discover magazine, proudly announces the creation of the first-of-its-kind, custom-produced Pluto globe, using data from the historic New Horizons Pluto mission of 2015.

“This is a first in history,” says David J. Eicher, Editor of Astronomy. “Little more than a year ago we had virtually no idea what Pluto’s surface looked like, and now we have a detailed globe showing 65 labeled features on this distant, beloved world. My old friend Clyde Tombaugh would be amazed and very proud.”

The high-quality desktop globe is a 12-inch diameter, injection-molded sphere that beautifully displays Pluto’s features from the New Horizons flyby — from the heart-shaped Tombaugh Regio, named for Clyde, to a myriad of smaller regions, craters, frozen plains, icy mountains, dune-like features, and apparent icy lakes that have flowed over the surface like glaciers do on Earth. Astronomy Senior Editor Michael Bakich painstakingly labeled the dozens of identified features.

Full article here:

http://cs.astronomy.com/asy/b/daves-universe/archive/2016/10/17/astronomy-magazine-announces-first-ever-pluto-globe.aspx

Is Pluto the new Mars? Hey, they wrote that, not me:

http://www.astronomy.com/news/year-of-pluto/2016/10/pluto-is-the-new-mars

DPS/EPSC update on New Horizons at the Pluto system and beyond

Posted By Emily Lakdawalla

2016/10/26 00:17 UTC

Last week’s Division for Planetary Sciences/European Planetary Science Congress meeting was chock-full of science from all over the solar system. A total of five sessions (one plenary, three oral, and one poster) was devoted to New Horizons at Pluto. It’s been a year since the flyby, a year that early science has had a chance to mature. What’s changed about our understanding of Pluto in that time?

First of all, an important reminder: New Horizons didn’t return its data instantly. We were told it would take 16 months to get all the data down. It took slightly more than that, but the data transmission is now complete, as of last weekend. Hats off to the New Horizons team for not only accomplishing the flyby, but safely returning all the data!

Of course, because data transmission took so long, scientists kept needing to modify analyses to incorporate freshly returned data. It’s like an image progressively coming into focus — the early data gave the team a good sense of what they had, but later data added depth and detail.

I’ll give some science summaries below, but first I want to share some news about data release, as well as a pretty picture. In his plenary talk, principal investigator Alan Stern announced that the second delivery of data to the Planetary Data System will come this month. This is going to include a lot of the nicest photos that New Horizons took through both high-resolution LORRI and lower-resolution-but-color MVIC cameras, and it was all downlinked without lossy compression, so it will be an exciting data release. There are two more releases planned for Pluto flyby data, in April and September 2017. Stern also mentioned that NASA has just announced a Data Analysis Program (DAP) for New Horizons, meaning that researchers not on the team can now propose for grant funds to work on the mission’s data.

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2016/10251718-dpsepsc-new-horizons-pluto.html

To quote:

Finally, there’s been a little more study of New Horizons’ next flyby target. Very little more study, because it’s so faint it’s accessible pretty much only with Hubble. (New Horizons won’t be able to spot it until fairly close to the date of the flyby.) Hubble now tells us it’s very red, typical for a classical cold Kuiper belt object, something that’s been disturbed very little over the age of the solar system. It’s probably 20 to 40 kilometers across, 1000 to 10000 times the mass of comet 67P. Stern said their initial plan for the flyby science includes mapping its composition, photo-mapping its surface, searching for satellites and dust, and searching for a coma.

It took over 15 months, but New Horizons has finally returned all of its data on the Pluto system to Earth:

http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20161027