Back in 1966, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Dwain Spencer laid out the principles of a fusion engine that burned deuterium and helium-3 (an isotope of helium with a nucleus of two protons and one neutron). Deuterium and helium-3 make a good combination for rocket propulsion because a fusion-based drive based on them releases one-hundredth the amount of radioactive neutrons than deuterium/tritium. A spacecraft using such an engine would, in other words, require far less shielding. And even more to the point, the protons and alpha particles produced by the reaction can be readily manipulated by a magnetic nozzle.

This was the background in 1971, when physicist Friedwardt Winterberg published a paper on fusion ignition using intense beams of electrons, speculating that such techniques could be used in rocket propulsion. Winterberg’s work took place in a context of energetic study, with newly declassified work becoming available that examined the use of lasers in igniting fusion. At Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, Rod Hyde was examining the use of deuterium and helium-3 in the form of frozen pellets that would be exploded at a rate of hundreds per second within an inertial confinement fusion reactor, using lasers to ignite the reaction.

All this comes to mind because of two papers recently made available by Winterberg, and the history of his own work as tapped by Project Daedalus. The latter was the British Interplanetary Society’s ambitious attempt to design a starship based on the technology of the 1970s extrapolated as far forward as was consistent with our knowledge of physics and engineering. The committees given the task of getting a payload to Barnard’s Star examined six propulsion concepts and finally decided on pulsed fusion using deuterium and helium-3. Winterberg’s work on igniting fusion via electron beams was a key factor in designing the vast Project Daedalus vehicle.

Image: The Project Daedalus craft approaches its flyby of Barnard’s Star. Credit: Adrian Mann.

The recent papers thus offer a look at still viable concepts whose evolution has played an important role in our interstellar thinking. Now at the University of Nevada (Reno), Winterberg explores how to create fusion ignition in pure deuterium without the use of a fission ‘trigger.’ To do this, he would use high-voltage pulses generated through what he describes as a ‘super Marx generator’ that ultimately creates a 107 Ampere-GeV proton beam in a compressed deuterium cylinder (a Marx generator is a type of circuit designed to produce such pulses).

Laser fusion will ultimately not work, because for a high gain the intense light flash of a thermonuclear microexplosion is going to destroy the entire optical laser ignition apparatus. The large Livermore laser is intended for weapons simulation. There, a low gain is sufficient.

It is the purpose of this communication to show, that with the proposed super Marx generator one may be able to ignite a pure deuterium thermonuclear micro-explosion.

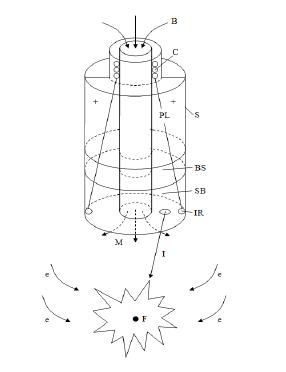

How to adapt the concept for space propulsion? Winterberg examines a propulsion system based on deuterium fusion, one in which “…a thermonuclear detonation wave is ignited in a small cylindrical assembly of deuterium with a gigavolt-multimegampere proton beam, drawn from the magnetically insulated spacecraft acting in the ultrahigh vacuum of space as a gigavolt capacitor.” Here are some specifics as drawn from the paper:

The spacecraft is positively charged against an electron cloud surrounding the craft, and with a magnetic field of the order 104 G, easily reached by superconducting currents flowing in an azimuthal direction, it is insulated against the electron cloud up to GeV potentials. The spacecraft and its surrounding electron cloud form a virtual diode with a GeV potential difference. To generate a proton beam, it is proposed to attach a miniature hydrogen filled rocket chamber R to the deuterium bomb target, at the position where the proton beam hits the fusion explosive… A pulsed laser beam from the spacecraft is shot into the rocket chamber, vaporizing the hydrogen, which is emitted through the Laval nozzle as a supersonic plasma jet. If the nozzle is directed towards the spacecraft, a conducting bridge is established, rich in protons between the spacecraft and the fusion explosive. Protons in this bridge are then accelerated to GeV energies, hitting the deuterium explosive.

It’s an audacious concept, one that, as Winterberg says, uses the entire spacecraft for electrostatic energy storage:

There, toroidal currents flowing azimuthally around the outer shell of the spacecraft, not only magnetically insulate the spacecraft against the surrounding electron cloud, but the currents also generate a magnetic mirror field which can reflect the plasma of the exploding fusion bomb. In addition, the expanding bomb plasma can induce large currents, and if these currents are directed to flow through magnetic field coils positioned on the upper side of the spacecraft, electrons from there can be emitted into space surrounding the spacecraft by thermionic emitters placed on the inner side of these coils in a process called inductive charging. It recharges the spacecraft for subsequent proton beam ignition pulses.

Image: Superconducting “atomic” spaceship, positively charged to GeV potential, with azimuthal currents and magnetic mirror M by magnetic field B. F fusion minibomb in position to be ignited by intense ion beam I, SB storage space for the bombs, BS bioshield for the payload PL, C coils pulsed by current drawn from induction ring IR. e electron flow neutralizing space charge of the fusion explosion plasma. Credit: Friedwardt Winterberg.

Winterberg recently presented this material at a Jet Propulsion Laboratory workshop, and the papers are available at the arXiv site. They’re “Ignition of a deuterium micro-detonation with a gigavolt super marx generator,” available here, and “Deuterium microbomb rocket propulsion,” online here. Brian Wang studies these concepts on his NextBigFuture site, and I see that Adam Crowl, who passed the original URLs along, has written them up at Crowlspace. Winterberg is exploring a range of technologies whose chief interest from the interstellar perspective is that they may be achievable in the relatively near-term without assuming breakthroughs in known physics.

How Fast could this go?

Would not this make a great part of a long term economic stimulus plan?

It is hard to sell intersteallar as a stimulus BUT if 10-20 years of serious investment could get us a 10 percent light craft I really think its sellable Who knows what spinoff benefits we could get!

The comment that laser fusion will not work is, to say the very least, misguided. The original reason why large lasers such as the system at Lawrence Livermore were built was to verify nuclear weapon systems WITHOUT exploding any… in line with the terms of the Test Ban Treaty, but the spin-off is the capability to push forward into fusion research for energy alone. Within about 2 years the first attempt will have been made for “Proof of Principle” at NIF in California and already other projects are preparing to carry that knowledge forward with an urgency appropriate to the scale of the global energy problem. For now we are stuck with relying on nuclear fission and CO2-producing fossil fuels to make the vast majority of our energy, but we need to act aggressively to solve this conundrum for the long term, and we know it will take decades to achieve it. If we knew it wouldn’t work we might as well resign ourselves now to a slow demise as a species… or at least a slow but inexorable return to the stone age. Outreach into space is a challenge we should also be fully engaged in, but let’s not stick our heads in the sand about nuclear fusion…. nor indeed fission or the 2-system hybrid approach (LIFE) it is achievable, but not on the timescales to which governments and media are accustomed to having their audience attuned. This requies an attention span beyond the life of governments… or even a long-running TV series !

Hi Paul;

This technology might permit velocities approaching 0.1 C, the same as was the target speed of the Project Daedalus vehicle (with enough fuel, of course).

With all the work being done within the medical field to study aging and perhaps extend the human life expectancy, I can see that optimized fusion rockets with a reasonable fuel supply that can reach 0.1 C could open up all of the stars within a 50 LY radius of Earth for manned interstellar missions: Assuming a human life expectancy of a comfortable 1,000 years.

All of us as space geeks and space heads should also look to medical science as perhaps one way that near term widespread interstellar travel will become possible. Funny thing is, if the human life expectancy can somehow in the far future be extended essentially forever, by such mechanisms as nanotech DNA repair, nanotech cellular rejuvination, extreme accident risk assessment and commensurate accident avoidance abilities, and other medical technologies, then perhaps as an extreme example of a human life expectancy being extended to a whopping 10 EXP 35 years, the lower experimental bounding value for proton decay, a world ship craft brought to 0.1 C could travel 10 EXP 34 LY from Earth in this extended lifetime neglecting the expansion of the universe. Assumming the expansion of the universe continues at more or less its current rate or that it speed up, not withstanding a cataclismic big rip, the craft would travel many orders of magnitude greater distance, yet, from the burned out husk of the Milk Way Galaxy.

Now, I will grant you that the above example is extreme, but who knows what indefinate human life expectancy will permit, even it the laws of special relativity prove inviolatable. I hope we do develope faster than light travel, but in the event that faster than light travel ultimately proves impossible, inertial travel through space at speeds ever closer to C will be suaght after prizes and the fun of interstellar propulsion research and development will still exist with ever new records to break. For the astronuats traveling in space ships that become capable of closing in on C ever more closely, effective superluminal travel velocities for these astronuats will result. Just imagine some crew members on a space ship traveling at a gamma factor of about 10 EXP 15. The crew would travel a distance though space equivalent to the diameter of the currently observable universe in about 10 EXP 3 seconds ships time, or in roughly the brief 20 minutes is took me to compose these comments, ships time. This, to me, is really quite profound.

We are now developing real space travel concepts that could take us to our stellar nieghboors this very century. If some huge bold funding program presents it self, many of us at Tau Zero could live to see the day when a fusion rocket powered 0.1 C to 0.2 C capable manned space craft is launched. Medical science will likely be an integral part in near term first generation manned interstellar travel missions. Thus, we should give the medical science folks our gratitude which I am sure we at Tau Zero already do.

Thanks;

Jim

Hi Paul

Winterberg has quite a few papers on the arXiv on the concept, but nothing detailed indicating the kind of performance he imagines a microfusion rocket could achieve.

Rather off-topic, but I just learned that the peer-review of Bussard’s Polywell WB-6 stage has been positive; see:

http://www.talk-polywell.org/bb/viewtopic.php?t=965

and

http://cosmiclog.msnbc.msn.com/archive/2008/12/16/1718741.aspx

Quote: “An EMC2 team headed by Los Alamos researcher Richard Nebel (…) has turned in its final report, and it’s been double-checked by a peer-review panel, Nebel told me today. Although he couldn’t go into the details, he said the verdict was positive”.