Small telescopes doing amazing things. That’s the theme of the day in exoplanet hunting, reinforced by the announcement of a new planet discovered by the Trans-Atlantic Exoplanet Survey (TrES). Small, automated equipment and off-the-shelf camera technology went into this work, which spotted the third transiting planet found with the kind of telescopes available to amateurs. “Hunting for planets with amateur equipment seemed crazy when we started the project,” says David Charbonneau, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, “but with this discovery the approach has become mainstream.”

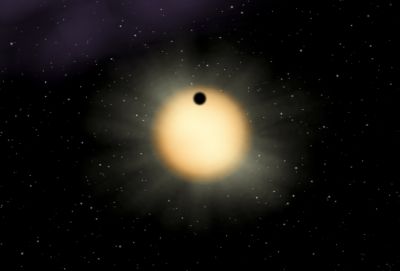

Image: A computer-generated simulation of TrES-2 crossing (transiting) the disk of its host star. TrES-2 transits farther from the disk center than any other known transiting planet. The transit of TrES-2 causes a drop in the brightness of its home star of about one and a half percent. This slight dimming of the star’s light was noticed and measured by the TrES researchers, who used the parameters of the transit to determine the planet’s mass, size and other properties. Credit: Jeffrey Hall, Lowell Observatory.

Here’s how TrES works: A network of small telescopes are automated to make wide-field exposures on observing runs that typically last about two months. The data, consisting of observations of tens of thousands of stars, are then run through software that examines the light curve of each, looking for the telltale signs of a planetary transit across the star. That’s no small task given the number of false positives that are bound to arise from binary star systems.

But when the data have been combed through and a suitable candidate found, the 10-meter instruments at the Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea (Hawaii) go to work to confirm the discovery. TrES also includes telescopes at the Palomar Observatory, the Planet Search Survey Telescope at Lowell Observatory in Arizona, and the Stellar Astrophysics and Research on Exoplanets (STARE) telescope in the Canary Islands.

Transits are terrifically useful finds because when they occur around nearby stars, they provide uniquely accurate size and mass measurements. The new world, TrES-2, blocks about one and a half percent of the light of its star, some 500 light years away in Draco. It’s larger than Jupiter and passes in front of the primary every two and a half days. Usefully, TrES-2 is also in a part of the sky that the upcoming Kepler mission will examine, allowing astronomers to plan ahead for a thorough examination of the planetary system. Adds Charbonneau, “TrES-2 will likely become the best-studied planet outside the Solar system once Kepler flies.”

This work has been submitted to the Astrophysical Journal Letters, and though I don’t yet see a link to it at arXiv, you can download a PDF of O’Donovan et al., “TrES-2: The First Transiting Planet in the Kepler Field” here. Also helpful by way of background is Charbonneau et al., “When Extrasolar Planets Transit Their Parent Stars,” available online.

The Transit Light Curve Project. VI. Three Transits of the Exoplanet TrES-2

Authors: Matthew J. Holman (1), Joshua N. Winn (2), David W. Latham (1), Francis T. O’Donovan (3), David Charbonneau (1), Guillermo Torres (1), Alessandro Sozzetti (1 and 4), Jose Fernandez (1), Mark E. Everett (5)

(Submitted on 23 Apr 2007)

Abstract: Of the nearby transiting exoplanets that are amenable to detailed study, TrES-2 is both the most massive and has the largest impact parameter. We present z-band photometry of three transits of TrES-2. We improve upon the estimates of the planetary, stellar, and orbital parameters, in conjunction with the spectroscopic analysis of the host star by Sozzetti and co-workers. We find the planetary radius to be 1.222 +/- 0.038 R_Jup and the stellar radius to be 1.003 +/- 0.027 R_Sun. The quoted uncertainties include the systematic error due to the uncertainty in the stellar mass (0.980 +/- 0.062 M_Sun). The timings of the transits have an accuracy of 25s and are consistent with a uniform period, thus providing a baseline for future observations with the NASA Kepler satellite, whose field of view will include TrES-2.

Comments:

15 pages, including 2 figures, accepted ApJ

Subjects:

Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as:

arXiv:0704.2907v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Matthew J. Holman [view email]

[v1] Mon, 23 Apr 2007 17:10:00 GMT (74kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0704.2907

Improving Stellar and Planetary Parameters of Transiting Planet Systems: The Case of TrES-2

Authors: A. Sozzetti (1,2), G. Torres (1), D. Charbonneau (1), D.W. Latham (1), M.J. Holman (1), J.N. Winn (3), J.B. Laird (4), F.T. O’Donovan (5) ((1) Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, (2) Osservatorio Astronomico di Torino, (3) Massachusetts Institute of Technology, (4) Bowling Green State University, (5) California Institute of Technology)

(Submitted on 23 Apr 2007)

Abstract: We report on a spectroscopic determination of the atmospheric parameters and chemical abundance of the parent star of the recently discovered transiting planet {TrES-2}. A detailed LTE analysis of a set of \ion{Fe}{1} and \ion{Fe}{2} lines from our Keck spectra yields $T_\mathrm{eff} = 5850\pm 50$ K, $\log g = 4.4\pm 0.1$, and [Fe/H] $= -0.15\pm 0.10$. Several independent checks (e.g., additional spectroscopy, line-depth ratios) confirm the reliability of our spectroscopic $T_\mathrm{eff}$ estimate. The mass and radius of the star, needed to determine the properties of the planet, are traditionally inferred by comparison with stellar evolution models using $T_\mathrm{eff}$ and some measure of the stellar luminosity, such as the spectroscopic surface gravity (when a trigonometric parallax is unavailable, as in this case). We apply here a new method in which we use instead of $\log g$ the normalized separation $a/R_\star$ (related to the stellar density), which can be determined directly from the light curves of transiting planets with much greater precision. With the $a/R_\star$ value from the light curve analysis of Holman et al. \citeyearpar{holman07b} and our $T_\mathrm{eff}$ estimate we obtain $M_\star = 0.980\pm0.062 M_\odot$ and $R_\star = 1.000_{-0.033}^{+0.036} R_\odot$, and an evolutionary age of $5.1^{+2.7}_{-2.3}$ Gyr, in good agreement with other constraints based on the strength of the emission in the \ion{Ca}{2} H & K line cores, the Lithium abundance, and rotation. The new stellar parameters yield improved values for the planetary mass and radius of $M_p = 1.198 \pm 0.053 M_\mathrm{Jup}$ and $R_p = 1.220^{+0.045}_{-0.042} R_\mathrm{Jup}$, confirming that {TrES-2} is the most massive among the currently known nearby ($d\lesssim 300$ pc) transiting hot Jupiters. [Abridged]

Comments:

27 pages, 5 figures, 1 table. Accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal

Subjects:

Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as:

arXiv:0704.2938v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Alessandro Sozzetti [view email]

[v1] Mon, 23 Apr 2007 08:06:38 GMT (112kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0704.2938

TrES Exoplanets and False Positives: Finding the Needle in the Haystack

Authors: Francis T. O’Donovan, David Charbonneau

(Submitted on 14 May 2007)

Abstract: Our incomplete understanding of the formation of gas giants and of their mass-radius relationship has motivated ground-based, wide-field surveys for new transiting extrasolar giant planets. Yet, astrophysical false positives have dominated the yield from these campaigns. Astronomical systems where the light from a faint eclipsing binary and a bright star is blended, producing a transit-like light curve, are particularly difficult to eliminate.

As part of the Trans-atlantic Exoplanet Survey, we have encountered numerous false positives and have developed a procedure to reject them. We present examples of these false positives, including the blended system GSC 03885-00829 which we showed to be a K dwarf binary system superimposed on a late F dwarf star. This transit candidate in particular demonstrates the careful analysis required to identify astrophysical false positives in a transit survey. From amongst these impostors, we have found two transiting planets. We discuss our follow-up observations of TrES-2, the first transiting planet in the Kepler field.

Comments:

v1. 6 pages, 5 figures. To appear in the ASP Conference Series: “Transiting Extrasolar Planets Workshop”, MPIA Heidelberg Germany, 25-28 September 2006. Eds: Cristina Afonso, David Weldrake & Thomas Henning

Subjects:

Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as:

arXiv:0705.1795v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Francis O’Donovan [view email]

[v1] Mon, 14 May 2007 19:19:00 GMT (92kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0705.1795

TrES-3: A Nearby, Massive, Transiting Hot Jupiter in a 31-Hour Orbit

Authors: Francis T. O’Donovan, David Charbonneau, Gáspár Á. Bakos, Georgi Mandushev, Edward W. Dunham, Timothy M. Brown, David W. Latham, Guillermo Torres, Alessandro Sozzetti, Géza Kovács, Mark E. Everett, Nairn Baliber, Márton G. Hidas, Gilbert A. Esquerdo, Markus Rabus, Hans J. Deeg, Juan A. Belmonte, Lynne A. Hillenbrand, Robert P. Stefanik.

(Submitted on 14 May 2007)

Abstract: We describe the discovery of a massive transiting hot Jupiter with a very short orbital period (1.30619 d), which we name TrES-3. From spectroscopy of the host star GSC 03089-00929, we measure T_eff = 5720 +- 150 K, logg=4.6 +- 0.3, and vsini

ASTRONOMERS FIND THEIR THIRD PLANET WITH NOVEL TELESCOPE NETWORK (TOP STORIES)

Astronomers using the Trans-atlantic Exoplanet Survey (TrES) network

of small telescopes are announcing today their discovery of a planet

twice the mass of Jupiter that passes in front of its star every 31

hours. The planet is in the constellation Hercules and has been

named TrES-3 as the third planet found with the TrES network.

Details: http://mr.caltech.edu/media/Press_Releases/PR12996.html

Largest Transiting Extrasolar Planet Found Around A Distant Star

August 6, 2007

Flagstaff, Ariz.– An international team of astronomers with the Trans-atlantic Exoplanet Survey announce today the discovery of TrES-4, a new extrasolar planet in the constellation of Hercules. The new planet was identified by astronomers looking for transiting planets – that is, planets that pass in front of their home star – using a network of small automated telescopes in Arizona, California, and the Canary Islands. TrES-4 was discovered less than half a degree (about the size of the full Moon) from the team’s third planet, TrES-3.

“TrES-4 is the largest known exoplanet,” said Georgi Mandushev, Lowell Observatory astronomer and the lead author of the paper announcing the discovery. “It is about 70 percent bigger than Jupiter, the Solar System’s largest planet, but less massive, making it a planet of extremely low density. Its mean density is only about 0.2 grams per cubic centimeter, or about the density of balsa wood! And because of the planet’s relatively weak pull on its upper atmosphere, some of the atmosphere probably escapes in a comet-like tail.”

The new planet TrES-4 was first noticed by Lowell Observatory’s Planet Search Survey Telescope (PSST), set up and operated by Edward Dunham and Georgi Mandushev. The Sleuth telescope, maintained by David Charbonneau (CfA) and Francis O’Donovan (Caltech), at Caltech’s Palomar Observatory also observed transits of TrES-4, confirming the initial detections. TrES-4 is about 1400 light years away and orbits its host star in three and a half days. Being only about 4.5 million miles from its home star, the planet is also very hot, about 1,600 Kelvin or 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit.

Full article here:

http://www.lowell.edu/media/releases.php?release=20070806

arXiv:0708.0834

Date: Mon, 6 Aug 2007 20:12:41 GMT (181kb)

Title: TrES-4: A Transiting Hot Jupiter of Very Low Density

Authors: Georgi Mandushev, Francis T. O’Donovan, David Charbonneau, Guillermo

Torres, David W. Latham, G\’asp\’ar \’A. Bakos, Edward W. Dunham, Alessandro

Sozzetti, Jos\’e M. Fern\’andez, Gilbert A. Esquerdo, Mark E. Everett,

Timothy M. Brown, Markus Rabus, Juan A. Belmonte, Lynne A. Hillenbrand

Categories: astro-ph

We report the discovery of TrES-4, a hot Jupiter that transits the star GSC

02620-00648 every 3.55 days. From high-resolution spectroscopy of the star we

estimate a stellar effective temperature of Teff = 6100 +/- 150 K, and from

high-precision z and B photometry of the transit we constrain the ratio of the

semi-major axis and the stellar radius to be a/R = 6.03 +/- 0.13. We compare

these values to model stellar isochrones to constrain the stellar mass to be M*

= 1.22 +/- 0.17 Msun. Based on this estimate and the photometric time series,

we constrain the stellar radius to be R* = 1.738 +/- 0.092 Rsun and the planet

radius to be Rp = 1.674 +/- 0.094 RJup. We model our radial-velocity data

assuming a circular orbit and find a planetary mass of 0.84 +/- 0.10 MJup. Our

radial-velocity observations rule out line-bisector variations that would

indicate a specious detection resulting from a blend of an eclipsing binary

system. TrES-4 has the largest radius and lowest density of any of the known

transiting planets. It presents a challenge to current models of the physical

structure of hot Jupiters, and indicates that the diversity of physical

properties amongst the members of this class of exoplanets has yet to be fully

explored.

http://arxiv.org/abs/0708.0834 , 181kb

Transit timing analysis of the exoplanets TrES-1 and TrES-2

Authors: M. Rabus, H. J. Deeg, R. Alonso, J. A. Belmonte, J. M. Almenara

(Submitted on 8 Sep 2009 (v1), last revised 10 Sep 2009 (this version, v2))

Abstract: The aim of this work is a detailed analysis of transit light curves from TrES-1 and TrES-2, obtained over a period of three to four years, in order to search for variabilities in observed mid-transit times and to set limits for the presence of additional third bodies. Using the IAC 80cm telescope, we observed transits of TrES-1 and TrES-2 over several years.

Based on these new data and previously published work, we studied the observed light curves and searched for variations in the difference between observed and calculated (based on a fixed ephemeris) transit times. To model possible transit timing variations, we used polynomials of different orders, simulated O-C diagrams corresponding to a perturbing third mass and sinusoidal fits. For each model we calculated the chi-squared residuals and the False Alarm Probability (FAP). For TrES-1 we can exclude planetary companions (>1 M_earth) in the 3:2 and 2:1 MMRs having high FAPs based on our transit observations from ground. Additionally, the presence of a light time effect caused by e. g. a 0.09 M_sun mass star at a distance of 7.8 AU is possible.

As for TrES-2, we found a better ephemeris of Tc = 2,453,957.63512(28) + 2.4706101(18) x Epoch and a good fit for a sine function with a period of 0.2 days, compatible with a moon around TrES-2 and an amplitude of 57 s, but it was not a uniquely low chi-squared value that would indicate a clear signal. In both cases, TrES-1 and TrES-2, we were able to put upper limits on the presence of additional perturbers masses.

We also conclude that any sinusoidal variations that might be indicative of exomoons need to be confirmed with higher statistical significance by further observations, noting that TrES-2 is in the field-of-view of the Kepler Space Telescope.

Comments: 10 pages; accepted for publication in A&A; replaced abstract

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:0909.1564v2 [astro-ph.EP]

Submission history

From: Markus Rabus [view email]

[v1] Tue, 8 Sep 2009 20:12:12 GMT (234kb)

[v2] Thu, 10 Sep 2009 14:15:04 GMT (234kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0909.1564

Detection of Planetary Emission from the Exoplanet TrES-2 using Spitzer /IRAC

Authors: Francis T. O’Donovan, David Charbonneau, Joseph Harrington, Sara Seager, N. Madhusudhan, Drake Deming, Heather A. Knutson

(Submitted on 16 Sep 2009)

Abstract: With the recent torrent of discoveries of new transiting planets, there have been ample candidates for observations using the Spitzer Space Telescope. We present here the results of our observations of TrES-2 using the Infrared Array Camera on Spitzer.

We monitored this transiting system during two secondary eclipses, when the planetary emission is blocked by the star. The resulting decrease in flux is 0.127%+-0.021%, 0.230%+-0.024%, 0.199%+-0.054%, and 0.359%+-0.060%, at 3.6, 4.5, 5.8, and 8.0 microns, respectively. We show that three of these flux contrasts are well fit by a black body spectrum with Teff = 1500 K, as well as by a more detailed model spectrum of a planetary atmosphere.

However, the planet-to-star flux ratio at 4.5 microns exceeds the expectation from the blackbody emission, which argues for a temperature inversion in the atmosphere of TrES-2.

The presence or absence of such an inversion in a planetary atmosphere has been predicted to be correlated with the amount of incident flux received by the planet, with hotter planets like TrES-2 being more likely to exhibit this inversion.

Our observation of emission at 4.5 microns that is indicative of an inversion supports the proposed importance of TiO and VO opacities in atmospheric models of highly irradiated gas giants. Furthermore, we find that the times of the secondary eclipses are consistent with previously published times of transit and the expectation from a circular orbit.

This implies that TrES-2 most likely has a circular orbit, and thus does not obtain additional thermal energy from tidal dissipation of a non-zero orbital eccentricity, a proposed explanation for the large radius of this planet.

Comments: 7 pages, 3 figures, 2 tables. Submitted to The Astrophysical Journal

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:0909.3073v1 [astro-ph.EP]

Submission history

From: Francis O’Donovan [view email]

[v1] Wed, 16 Sep 2009 17:53:49 GMT (47kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0909.3073