It’s long been my belief that getting more private money into space research is essential, given the uncertainties of government funding and the need to inject outside ideas and enthusiasm into the game. We’re already seeing what will, I think, become explosive growth in commercial rocket ventures aimed at finding cheaper and better ways to reach low-Earth orbit. On the interstellar front, the Tau Zero Foundation is being built to parlay philanthropic donations into a solid base for funding cutting edge research into advanced propulsion technologies.

The hunt for exoplanets also partakes of this largesse, as witness a $600,000 gift from the Gloria and Kenneth Levy Foundation that will fund a new spectrometer designed for the Automated Planet Finder being built at Lick Observatory. The instrument will check twenty-five stars every night, studying 2000 stars within 50 light years over the next decade. Doppler shifts in the wavelengths of starlight provide the telltale signs of an orbiting planet, and APF should be available for such study every clear night of the year.

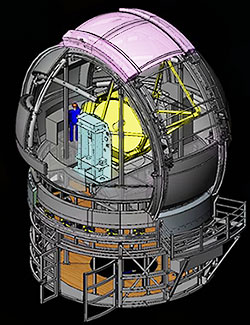

Image: The 2.4-meter automated telescope and enclosure with high-resolution spectrograph. In the schematic drawing above, the telescope is yellow and the spectrograph light blue. Credit: Lick Observatory.

Steven Vogt, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz, is the designer of the spectrometer and a principal scientist on the California-Carnegie Planet Search team. Noting the challenge facing the APF instrument, Vogt has this to say:

“We’re looking for shifts in the spectrum on the focal plane of the spectrometer that are on the order of a thousandth of a pixel. And we have to be able to find those shifts and track them from year to year, summer to winter, spring to fall. The shifts we’re looking for amount to a distance of about 80 atoms on the surface of the CCD [camera].”

The ultimate target: Earth-like planets in the habitable zones of the target stars. The new spectrometer brings unique power to the hunt. Whereas older spectrometers were room-sized and more, the new instrument is small enough (the size of a telephone booth) to be bolted directly onto the telescope. That means telescope operators can forgo the fiber-optic cables that would normally carry telescope light to a separate spectrometer installation, losing 30 percent of it along the way.

Moreover, the spectrometer’s steel and magnesium skeleton adjusts its shape as temperatures change, so that the optics remain optimally aligned. And while the Automated Planet Finder instrument itself is less than a quarter of the size of the 10-meter Keck telescopes, the largest optical instruments currently in use, hopes are high that the latest engineering, coupled with the new spectrometer design, will produce an instrument two to four times more efficient than Keck.

To be sure, the Automated Planet Finder receives its share of government funding from NASA, the U.S. Naval Observatory, the National Science Foundation and the Lick Observatory itself. But this act of philanthropy reminds us of the continuing interest in interstellar subjects that, while low-key, can over time help to engage the public in our quest for terrestrial worlds around other stars. Needless to say, progress toward finding small planets in a distant star’s habitable zone should galvanize even more interest and, let’s hope, other such acts of generosity.

How about using such an instrument for the Keck telescope(s)?

Is such a thing foreseen as well? I mean, that would obviously produce an even much more efficient instrument.

Ronald, I know of no plans to do this, but the new spectrometer is going to have to be put through its paces first at APF, and I would think if its design is successful, other observatories will be quite interested.

TEDI: the TripleSpec Exoplanet Discovery Instrument

Authors: Jerry Edelstein (Berkeley), Matthew Ward Muterspaugh (Berkeley), David J. Erskine (LLNL), W. Michael Feuerstein (Berkeley), Mario Marckwordt (Berkeley), Ed Wishnow (Berkeley), James P. Lloyd (Cornell), Terry Herter (Cornell), Phillip Muirhead (Cornell), George E. Gull (Cornell), Charles Henderson (Cornell), Stephen C. Parshley (Cornell)

(Submitted on 10 Oct 2007)

Abstract: The TEDI (TripleSpec – Exoplanet Discovery Instrument) will be the first instrument fielded specifically for finding low-mass stellar companions.

The instrument is a near infra-red interferometric spectrometer used as a radial velocimeter. TEDI joins Externally Dispersed Interferometery (EDI) with an efficient, medium-resolution, near IR (0.9 – 2.4 micron) echelle spectrometer, TripleSpec, at the Palomar 200″ telescope. We describe the instrument and its radial velocimetry demonstration program to observe cool stars.

Comments: 6 Pages, To Appear in SPIE Volume 6693, Techniques and Instrumentation for Detection of Exoplanets III

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0710.2132v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Matthew Muterspaugh [view email]

[v1] Wed, 10 Oct 2007 22:30:43 GMT (764kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0710.2132

Externally Occulted Terrestrial Planet Finder Coronagraph: Simulations and Sensitivities

Authors: Richard G. Lyon, Sally Heap, Amy Lo, Webster Cash, Glenn D. Starkman, Robert J. Vanderbei, N. Jeremy Kasdin, Craig J. Copi

(Submitted on 7 Dec 2007)

Abstract: A multitude of coronagraphic techniques for the space-based direct detection and characterization of exo-solar terrestrial planets are actively being pursued by the astronomical community. Typical coronagraphs have internal shaped focal plane and/or pupil plane occulting masks which block and/or diffract starlight thereby increasing the planet’s contrast with respect to its parent star. Past studies have shown that any internal technique is limited by the ability to sense and control amplitude, phase (wavefront) and polarization to exquisite levels – necessitating stressing optical requirements.

An alternative and promising technique is to place a starshade, i.e. external occulter, at some distance in front of the telescope. This starshade suppresses most of the starlight before entering the telescope – relaxing optical requirements to that of a more conventional telescope. While an old technique it has been recently been advanced by the recognition that circularly symmetric graded apodizers can be well approximated by shaped binary occulting masks. Indeed optimal shapes have been designed that can achieve smaller inner working angles than conventional coronagraphs and yet have high effective throughput allowing smaller aperture telescopes to achieve the same coronagraphic resolution and similar sensitivity as larger ones.

Herein we report on our ongoing modeling, simulation and optimization of external occulters and show sensitivity results with respect to number and shape errors of petals, spectral passband, accuracy of Fresnel propagation, and show results for both filled and segmented aperture telescopes and discuss acquisition and sensing of the occulter’s location relative to the telescope.

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Journal reference: Proceedings of SPIE 6687, San Diego CA, August 2007

Cite as: arXiv:0712.1105v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Richard Lyon [view email]

[v1] Fri, 7 Dec 2007 10:11:30 GMT (2816kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0712.1105