Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

OSIRIS-REx: Asteroid Sample Site Flyover

The latest operations of the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft at asteroid Bennu remind me how powerful a wave we’ve unleashed in the coupling of robotics and ever more capable spacecraft components. We’re not exactly at the stage of ‘routine’ asteroid missions, but Hayabusa2 and OSIRIS-REx when seen in the context of upcoming missions like NASA’s DART experiment and the European Space Agency’s Hera are part of our renaissance of this class of object, with results beneficial to science but also practically useful in terms of future impact mitigation. More on DART and Hera tomorrow.

Small objects have plenty to say about our future in space, and I haven’t even mentioned Lucy, which will be studying multiple Jupiter trojans, or the Psyche mission targeting what may be the exposed core of a planetary embryo, or for that matter, the remarkably successful Dawn, which unlocked so many mysteries at Vesta and Ceres. It goes without saying that having an operational spacecraft in the Kuiper Belt is likewise a sign that we are getting pretty good at doing robotic exploration even as we continue to wrestle with the human role on the Moon and Mars.

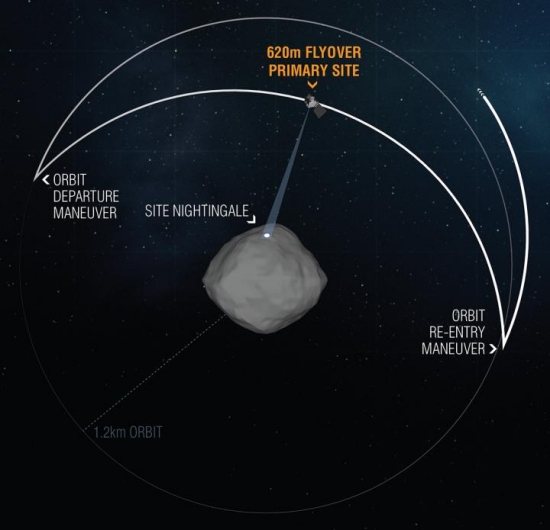

OSIRIS-REx (Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security-Regolith Explorer) has now completed a 620 meter flyover of the site called ‘Nightingale’ on its target asteroid as part of the mission’s analysis of the primary sample collection site. To make this happen, the spacecraft left a 1.2 kilometer home orbit and performed an 11-hour transit over the asteroid, accumulating data about the 16-meter wide sample site and returning to safe orbit.

Image: During the OSIRIS-REx Reconnaissance B flyover of primary sample collection site Nightingale, the spacecraft left its safe-home orbit to pass over the sample site at an altitude of 0.4 miles (620 m). The pass, which took 11 hours, gave the spacecraft’s onboard instruments the opportunity to take the closest-ever science observations of the sample site. Credit: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona.

The spacecraft has been compiling a Natural Feature Tracking image catalog by way of mapping the tiniest details among the boulders and craters of the landing site. The OSIRIS-REx team is also studying observations from the spacecraft’s Thermal Emissions Spectrometer (OTES), the OSIRIS-REx Visual and InfraRed Spectrometer (OVIRS), the OSIRIS-REx Laser Altimeter (OLA), and the MapCam color imager.

So there’s a lot happening at Bennu, including an upcoming flyover, scheduled for February 11, of the backup sample site, which has been given the name ‘Osprey.’ Further flybys in March (Nightingale) and May (Osprey) will take OSIRIS-REx even closer to the surface as the spacecraft goes into Reconnaissance C phase, operating at 250 meters. Assuming all goes well, a multi-hour sampling maneuver will begin in August, using the spacecraft’s robotic arm and sampler head to make contact with the asteroid. We will eventually gain between 60 and 2000 grams of surface material, with return to Earth scheduled for September of 2023.

Image: This artist’s concept shows OSIRIS-REx contacting asteroid Bennu with its sample return instrument. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Dwarf Novae: Mining Kepler Data for New Discoveries

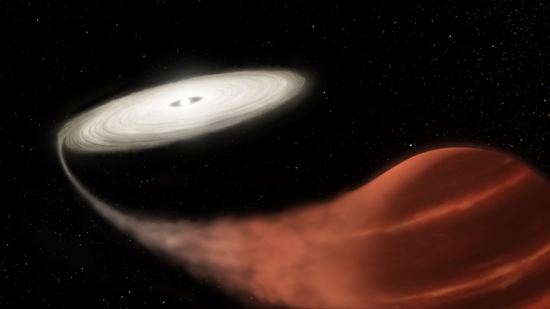

Cataclysmic variable stars (CVs) are binary phenomena, usually consisting of a white dwarf that is accreting material out of a nearby companion star. As you would imagine, a wide range of CVs in various stages of accretion and subsequent outburst can be detected. When the accretion disk around the white dwarf becomes unstable, we get what is known as a dwarf nova (DN), and in systems with orbital periods less than two hours, there can be much more violent outbursts, feeding off orbital resonances in the orbit of the two stars.

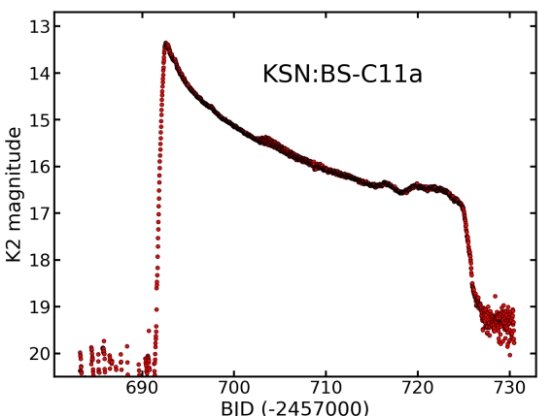

Now we have a newly discovered cataclysmic variable (KSN:BS-C11a) in an interesting configuration, a white dwarf apparently feeding off a brown dwarf companion that is about 10 times less massive. The ‘super-outburst’ from the dwarf nova turned up in data from the decommissioned Kepler Space Telescope. Grad student Ryan Ridden-Harper (Australian National Observatory), lead author of the paper on this work, likes to refer to this cataclysmic variable as ‘a vampire star system.’ Whatever we call it, the level of activity here is noteworthy:

“The incredible data from Kepler reveals a 30-day period during which the dwarf nova rapidly became 1,600 times brighter before dimming quickly and gradually returning to its normal brightness. The spike in brightness was caused by material stripped from the brown dwarf that’s being coiled around the white dwarf in a disk. That disk reached up to 11,700 degrees Celsius at the peak of the super-outburst.”

Image: An artist’s impression of a star ‘feeding’ off a nearby brown dwarf. Credit: NASA and L. Hustak (STScI)

Still unexplained is the slow rise in brightness that preceded the outburst. Ridden-Harper has been working with colleagues at ANU as well as the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and the University of Notre Dame. What catches my eye about the discovery of this bright transient is the data mining that turned it up. The team had been searching for new transients in the K2 and Kepler campaigns in a project known as K2: Background Survey. The idea here is that each science target in the data is accompanied by background pixels that have been observed at high cadence, meaning a short time period before re-observing the same target.

These background pixels, the authors note, can contain transient signals that have thus far gone undetected. The paper describes the K2: Background Survey as:

…a systematic search for transients in K2/Kepler background pixels. K2:BS independently analyses each pixel to detect abnormal behaviour. This is done by searching for pixels that rise above a brightness threshold set from the median brightness and standard deviation through a campaign. Telescope motion presents a challenge in candidate detection as science targets may drift into background pixel, triggering false events. False triggers are screened by vetting of events that last < 1 day, chosen for candidates with the 6 hourly telescope resets. Coincident pixels that pass the vetting procedure are grouped into an event mask. All candidate events are checked against the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED) 1 and the SIMBAD database (Wenger et al. 2000) to identify potential hosts.

As to the parameters of the system, the brown dwarf orbits the white dwarf every 83 minutes at a distance of approximately 400,000 kilometers, close enough to allow the rapid growth of the accretion disk as material spirals from the brown dwarf inward toward the host star. The Kepler cadence of 30 minutes turns out to have been the key to making these observations, which are particularly useful because only about 100 such dwarf novae systems have been catalogued.

Image: This is Figure 3 from the paper. Caption: The K2/Kepler light curve of the transient KSN:BS-C11a shown with the 30-minute cadence. The time axis is shown in barycentric Julian days and the flux has been converted to Kepler magnitudes. Credit: Ridden-Harper et al.

Thus Kepler/K2 keeps on producing good science, in this case finding a transient whose rarity stems partially from the years or decades such a system can spend between outbursts. We shouldn’t be too surprised that Kepler data can produce such results — after all, the telescope was designed to study the transits of planets across the face of a star, making it ideal for spotting any objects that brighten or dim over time — but now we can see the potential for detecting other rare transient events both in archival data and data from ongoing missions like TESS.

The paper is Harper et al., “Discovery of a new WZ Sagittae-type cataclysmic variable in the Kepler/K2 data,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society,” Vol. 490, Issue 4 pp. 5551-5559 (abstract).

From Spitzer to JWST’s Early Targets

Yesterday’s post on the Spitzer Space Telescope leads naturally to the targets it produced for its successor. For when Spitzer’s mission ends on January 30, we have the far more powerful James Webb Space Telescope, also operating at infrared wavelengths, in queue for a 2021 launch. In many ways, Spitzer has been the necessary precursor for JWST, for it was the need to operate a telescope at extremely low temperatures in order to maximize infrared sensitivity that drove Spitzer design. JWST must maintain its gold-coated beryllium mirror at similarly precise temperatures.

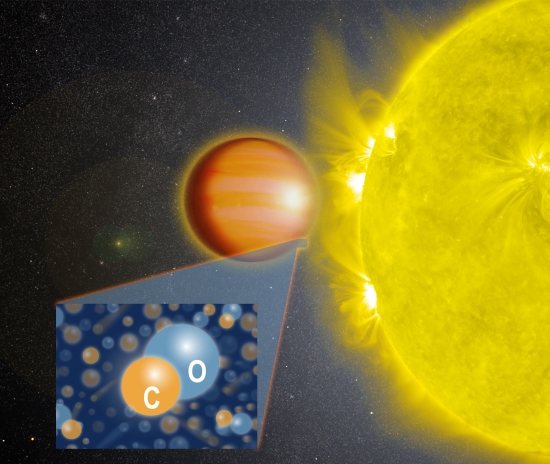

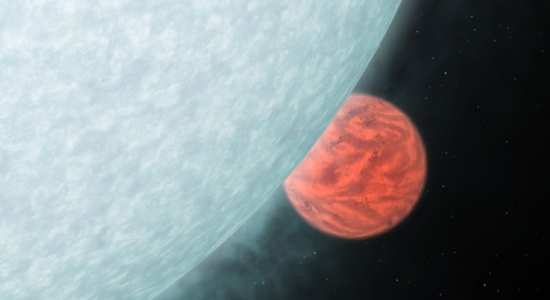

With over 8,700 scientific papers published based on Spitzer findings, a number that will continue to grow for many years, a path has been charted that JWST will follow in the form of observations early in its mission. Consider WASP-18b, a gas giant of ten times Jupiter mass in a tight orbit around its star. Data from both Spitzer and Hubble showed in 2017 that the planet is laden with carbon monoxide and all but devoid of water vapor. No other extrasolar planet can match this one in the way carbon monoxide dominates its upper atmosphere.

What’s going on in the atmosphere of this planet merits close study because it’s extreme even for ‘hot Jupiters’ in being so close to its star that it may not survive another million years. Expect a long look from JWST into the processes at work here. Nikku Madhusudhan (University of Cambridge) was a co-author on the 2017 paper describing the WASP-18b findings:

“The only consistent explanation for the data is an overabundance of carbon monoxide and very little water vapor in the atmosphere of WASP-18b, in addition to the presence of a stratosphere. This rare combination of factors opens a new window into our understanding of physicochemical processes in exoplanetary atmospheres.”

The image below implies the method: Transmission spectroscopy. We can look at the light of the star passing through the atmosphere of the planet as it moves around the star in its orbit.

Image: A NASA-led team of scientists determined that WASP-18b, a “hot Jupiter” located 325 light-years from Earth, has a stratosphere that’s loaded with carbon monoxide, or CO, but has no signs of water. Credit: Goddard Space Flight Center.

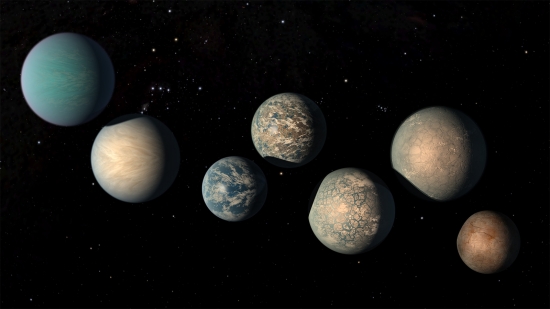

At TRAPPIST-1, expect the fourth planet, TRAPPIST-1e, to receive early JWST scrutiny because of its density and surface gravity, both similar to Earth’s, in combination with incoming stellar flux sufficient to keep temperatures in the range needed for water on the surface. JWST should be able to tell us whether this planet does indeed have an atmosphere, and assuming it does, whether molecules like carbon dioxide or water vapor are present.

Here again Spitzer helped set the table, working with ground-based telescopes to confirm the first two candidates (found by the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope in Chile) and discover the other five. Our ideas of what these planets look like will change with the new data JWST, 1000 times more powerful than Spitzer, will bring in. The Hubble instrument has not been able to detect evidence for a hydrogen-dominated atmosphere on TRAPPIST-1d, e and f, making rocky composition likely. But it’s going to take JWST to further clarify the presence of atmospheres on the seven worlds and begin the study of their chemistry.

All of that should take what is a very fanciful image (below) and help us determine how far from reality it actually is. At present we’re simply injecting sparse data into the realm of art. As Nikole Lewis (Cornell University) says, “The diversity of atmospheres around terrestrial worlds is probably beyond our wildest imaginations. Getting any information about air on these planets is going to be very useful.”

Image: This artist’s concept shows what the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system may look like, based on available data about the planets’ diameters, masses and distances from the host star, as of February 2018. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

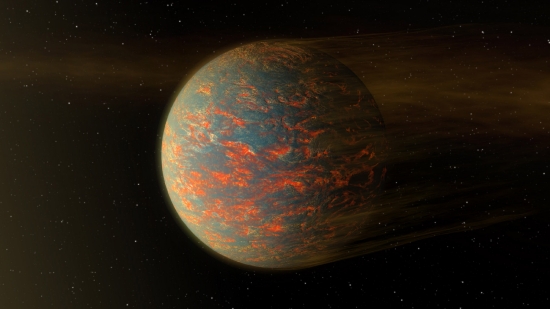

Spitzer’s work on 55 Cancri e will also inform early JWST studies of the system. Spitzer was able to produce data leading to the first temperature map of a super-Earth, in this case an apparently rocky world about twice the size of our own. Lava flows may be the cause of the extreme temperature swings between one side of the planet and the other, as noted in 2016 by Brice Olivier Demory (University of Cambridge), who was lead author of the paper in Nature:

“Our view of this planet keeps evolving. The latest findings tell us the planet has hot nights and significantly hotter days. This indicates the planet inefficiently transports heat around the planet. We propose this could be explained by an atmosphere that would exist only on the day side of the planet, or by lava flows at the planet surface.”

Spitzer put in 80 hours of infrared telescope time in the 55 Cancri e work, watching this tidally locked world move about its star and allowing the construction of the temperature map. Mission scientists pushed Spitzer hard in accumulating their data, using novel calibration techniques to extract maximum results from a detector that had not been design to work at such high precision. Now JWST will help sharpen the map’s focus to explain its unusual temperature swings, which argue against a thick atmosphere and global temperature distribution.

Image: 55 Cancri e is tidally locked to its star, just as our moon is to Earth, which means that one side always sizzles under the heat of its star while the other side remains in the dark. If the planet were covered in lava, then the hot, sun-facing side of the planet would have liquid lava flows, while the colder, dark side would see solidified lava rock. The hardened lava would be unable to transport heat across the planet, explaining why Spitzer detected that the cold side of the planet is much colder than the hot side. Such a lava planet, if it exists, would have dust streaming off of it, as illustrated here. Radiation and winds from the nearby star would blow off the material. Scientists say that future observations with NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope should provide more details about the nature of this exotic world. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Both Spitzer and Webb are sensitive to the infrared glow of gas and dust orbiting in circumstellar rings around stars, which means JWST will be able to extend our knowledge of planetary formation. The same sensitivity will make JWST the instrument of choice in the study of brown dwarfs, an area where Spitzer has already been able to examine clouds in brown dwarf atmospheres. What’s interesting here are the differences between the distribution and motion of clouds on brown dwarfs and the atmospheric boiling seen on true stars. JWST will investigate winds that seem reminiscent of the belts of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

I’ve focused on exoplanetary targets here, but of course the handoff from Spitzer to JWST will also involve using the large surveys of Spitzer and the Hubble instrument to furnish JWST with targets like GN-z11, now the most distant galaxy ever measured. Sean Carey is manager of the Spitzer Science Center at Caltech/IPAC in Pasadena:

“Spitzer surveyed thousands of galaxies, mapped the Milky Way and performed other groundbreaking feats by looking at large areas of the sky. Webb won’t have this capability, but it will revisit some of the most interesting targets in the Spitzer surveys to reveal them in amazing clarity.”

JWST’s higher sensitivity should make it possible to find galaxies that are even older. It will also home in on luminous infrared galaxies (LIRG), which Spitzer found to be producing far more energy per second than typical galaxies, most of it in the form of far-infrared light. Star formation and galactic mergers come into focus, as does the growth of supermassive black holes. All of this depends, of course, on getting a fabulously complex telescope plagued by cost overruns into its future home at the L2 Lagrangian point 1.5 million kilometers from the Earth.

All launches are scary, but this one more than most. We need Spitzer’s successor to fly.

Looking Back at the Spitzer Space Telescope

The Spitzer Space Telescope, which is to end its mission on January 30, has a special place in my memory. I was making a trip to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory as part of the research for my Centauri Dreams book when I noticed on a monitor a countdown — still in days — for the launch of Spitzer, then known as the Space Infrared Telescope Facility (SIRTF).

The observatory was launched on the 25th of August, 2003. I remember hot Pasadena weather, a conversation with aerospace legend Adrian Hooke (he was a member of the Kennedy Space Center launch team for Apollo 9, 10, 11 and 12, among much else), a rousing talk with Humphrey “Hoppy” Price about interstellar possibilities. So many good conversations, some serious interviews, and a growing enthusiasm for interstellar flight.

But Spitzer had my attention because it was the next mission, one of the Great Observatory missions which included the Hubble Space Telescope, the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, and Spitzer itself. The infrared observatory lasted longer than anyone expected and continued to function even after exhausting its helium coolant in 2009, at which point the ‘cold mission’ ended, but the ‘warm mission’ would last over a decade.

‘Warm’ and ‘cold’ are obviously relative terms when we talk about objects in space. With a full stock of coolant, the spacecraft could maintain temperatures as low as minus 267 degrees Celsius, so yes, that’s ‘cold.’ But Spitzer functioned a long way from Earth, so that even the ‘warm’ mission could operate at minus 244° C, and that enabled continued observations in two infrared wavelengths. We got more than 16 years of use out of Spitzer, another case among many of a mission’s science team working all the angles to keep their craft alive.

Image: The Spitzer Space Telescope (formerly the Space Infrared Telescope Facility or SIRTF) is readied for launch at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, in 2003. Credit: NASA.

The beauty of working at infrared wavelengths is that you can see things that are too cold to emit much visible light. For our purposes, that includes brown dwarfs and exoplanets, but the observatory has also excelled at studying distant galaxies, including (in conjunction with Hubble observations) the most distant galaxy yet observed, GN-z11, which is seen in the direction of Ursa Major as it was 13.4 billion years in the past. Again of direct relevance to Centauri Dreams readers is Spitzer’s work on interstellar dust, whose chemical composition, studied via spectroscopy, can help us learn more about what goes into planet formation.

This is the instrument that, in 2007, gave us the first identification of molecules in the atmosphere of an exoplanet — two of them, actually. HD 209458b and HD 189733b are ‘hot Jupiters’ and the use of transmission spectroscopy to study their atmospheres points us toward the future prospect of searching for biosignatures on small, rocky planets like Earth. In 2010, Spitzer was part of the discovery of a planet 13,000 light years away, found via gravitational microlensing. Back in 2005, it made direct observations of the ‘hot Jupiters’ HD 209458b and TrES-r1, the first telescope to directly observe light from a planet in another stellar system.

Image: Spitzer was the first telescope to directly observe light from a planet outside our solar system. Prior to that, exoplanets had been observed only indirectly. This accomplishment kicked off a new era in exoplanet science, and marked a major milestone on the journey toward detecting possible signs of life on rocky exoplanets. Two studies released in 2005 reported direct observations of the warm infrared glows from two previously detected “hot Jupiter” planets, designated HD 209458b and TrES-r1. Hot Jupiters are gas giants similar to Jupiter or Saturn, but are positioned extremely close to their parent stars. From their toasty orbits, they soak up ample starlight and shine brightly in infrared wavelengths. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

I won’t even try to go through all of Spitzer’s accomplishments, but I do need to mention the seven Earth-sized planets around TRAPPIST-1, which Spitzer data, over 500 hours worth, helped scientists identify via transit methods. And I have to include the ‘weather map’ of HD 189733b, a chart of temperature variations over the surface of a gas giant. Sean Carey, manager of the Spitzer Science Center at Caltech, has this to say about the instrument:

“When Spitzer was being designed, scientists had not yet found a single transiting exoplanet, and by the time Spitzer launched, we still knew about only a handful. The fact that Spitzer became such a powerful exoplanet tool, when that wasn’t something the original planners could have possibly prepared for, is really profound. And we generated some results that absolutely knocked our socks off.”

So true! From its Earth-trailing orbit, Spitzer was a long way from our planet’s heat and could offer greater sensitivity than other instruments, especially considering that it could detect some infrared wavelengths that could not be seen through the filter of our atmosphere. What a marvelous run for this observatory, whose decommissioning leads us directly into the launch of the infrared James Webb Space Telescope. We can only hope that the highly complex JWST makes it safely into space and that it lives to see as many mission extensions (5) as the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Image: This dazzling infrared image from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope shows hundreds of thousands of stars crowded into the swirling core of our spiral Milky Way galaxy. In visible-light pictures, this region cannot be seen at all because dust lying between Earth and the galactic center blocks our view. In this false-color picture, old and cool stars are blue, while dust features lit up by blazing hot, massive stars are shown in a reddish hue. Both bright and dark filamentary clouds can be seen, many of which harbor stellar nurseries. The plane of the Milky Way’s flat disk is apparent as the main, horizontal band of clouds. The brightest white spot in the middle is the very center of the galaxy, which also marks the site of a supermassive black hole. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Spitzer was a pathfinder in many areas of astronomical research, but a kind of personal pathfinder for me, as I’ve always associated its observations with my work as a chronicler of this field. An observatory designed to study “the cold, the old and the dusty,” as NASA likes to say, taught us about objects as close as nearby asteroids and as far as the oldest galaxies. The frustrations of human spaceflight in the post-Apollo era have to be balanced against the brilliance of science missions like Spitzer, which have charted a path forward that should one day lead to direct observations of planets where life may even now be flourishing.

An Impact-Driven End to ‘Snowball Earth’?

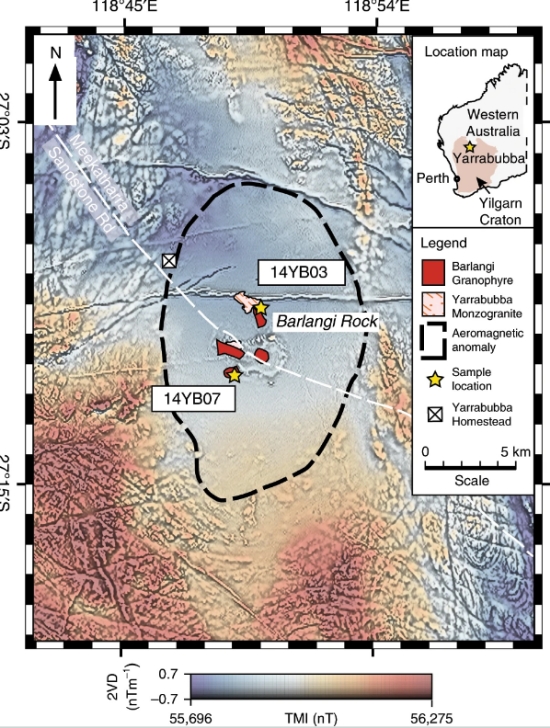

The oldest preserved impact structure on Earth appears to be at Yarrabubba in Western Australia, where a magnetic anomaly about 20 kilometers in diameter has been interpreted to be a remnant of an original impact crater 70 kilometers across. Here, what had been an approximate age of 2.65 to 1.075 billion years has now been constrained to 2.229 billion years, making Yarrabubba 200 million years older than the next oldest impact.

A team led by Timmons Erickson (Curtin University) analyzed the minerals zircon and monazite at the site. Their sample showed shock recrystallization (in the form of so-called neoblasts) from an asteroid strike, the analysis of which allowed them to pin down the structure’s age. A paper just out in Nature Communications reports on the team’s use of uranium-lead (U–Pb) dating to investigate the age of the shock features and impact melt.

A global climate change may have occurred as a result of this impact, perhaps one with consequences for so-called ‘snowball Earth,’ a hypothesis of almost planet-wide ice cover in one or more periods before 650 million years ago. This impact conceivably ended the ice era.

Image: This is Figure 1 from the paper. Caption: Composite aeromagnetic anomaly map of the Yarrabubba impact structure within the Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia, showing the locations of key outcrops and samples used in this study. The image combines the total magnetic intensity (TMI, cool to warm colours) with the second vertical derivative of the total magnetic intensity (2VD, greyscale) data. The demagnetised anomaly centred on the outcrops of the Barlangi granophyre is considered to be the eroded remnant of the central uplift domain, which forms the basis of the crater diameter of 70?km. Prominent, narrow linear anomalies that cross-cut the demagnetised zone with broadly east-west orientations are mafic dykes that post-date the impact structure. Credit: Erickson et al.

The result is intriguing because the Yarrabubba crater was made at a time when rocks on many continents provide evidence of glacial conditions, and oceans were becoming more oxygenated. Thus co-author Nicholas Timms (Curtin University):

“The age of the Yarrabubba impact matches the demise of a series of ancient glaciations. After the impact, glacial deposits are absent in the rock record for 400 million years. This twist of fate suggests that the large meteorite impact may have influenced global climate.

“Numerical modelling further supports the connection between the effects of large impacts into ice and global climate change. Calculations indicated that an impact into an ice-covered continent could have sent half a trillion tons of water vapour – an important greenhouse gas – into the atmosphere. This finding raises the question whether this impact may have tipped the scales enough to end glacial conditions.”

An end to a period of snowball Earth? Perhaps so. Certainly the work is a reminder of how much we have to learn about crater structures on our own planet, and how much we need to acquire precise ages for them. The impact’s effects, assuming a continental ice sheet, would have been powerful. The team’s numerical models of a 70-kilometer impact crater driven into a granitic target with overlying ice sheet (modeled at from 2 to 5 kilometers in thickness) show the almost instantaneous vaporization of huge amounts of ice. From the paper:

The vapourised ice corresponds to between 9?×?1013 and 2?×?1014?kg of water vapour being jetted into the upper atmosphere within moments of the impact… Impact-generated water vapour in the lower atmosphere would have condensed and rapidly precipitated as rain and snow with no significant long-term climate effects, or could have even triggered widespread glacial conditions via cloud albedo effects during interglacial periods. However, ejection of high-altitude water vapour has potential for greenhouse radiative forcing, depending critically on atmospheric residence time.

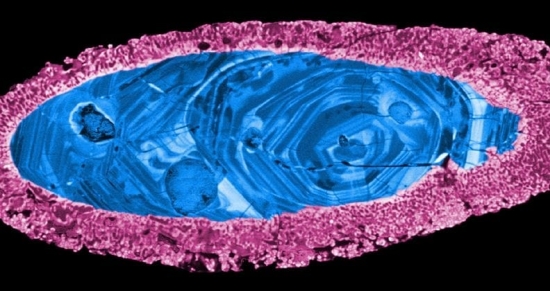

Image: Zircon crystal used to date the Yarrabubba impact. Credit: Erickson et al.

The authors are quick to note how difficult it is to model the impact’s effects due to our uncertainties about the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere in the period in question. But they note that the atmosphere would have contained only a fraction of current levels of oxygen, making it likely that huge amounts of H2O vapor released instantaneously into the atmosphere would have had global ramifications.

While the ‘snowball Earth’ hypothesis dominates coverage of this paper, I think the broader significance is in the nature of ongoing research. We can inspect the impact record on surfaces like the Moon due to the lack of atmospheric erosion, but on Earth we face the latter as well as the obscuring effects of tectonics. Until we have a better record of terrestrial impacts, we won’t understand the links between impacts and changes to global climate. At least we have the notable exception of the Chicxulub crater in the Gulf of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, a feature under intense study.

Going back much farther in time, however, we’re looking at poorly constrained and ambiguous impact evidence, a problem that this paper addresses for a period that was hitherto lacking in impact analysis at this level of detail. More broadly, we’re reminded as well of the shaping effect of bombardment as young terrestrial planets evolve, and should always be mindful of the contingencies forced upon nascent worlds by system debris.

The paper is Erickson et al., “Precise radiometric age establishes Yarrabubba, Western Australia, as Earth’s oldest recognised meteorite impact structure,” Nature Communications 11, article no: 300, published online 21 January 2020. Full text.

A Deep Dive into Tidal Lock

Mention red dwarf habitable zones and tidal lock invariably comes up. If a planet is close enough to a dim red star to maintain temperatures suitable for life, wouldn’t it keep one face turned toward it in perpetuity? But tidal lock, as Ashley Baldwin explains in the essay below, is more complex than we sometimes realize. And while there are ways to produce temperate climate models for such planets, tidal lock itself is a factor in not just M-dwarfs, but K- and even G-class stars like the Sun. Flip a few starting conditions and Earth itself might have been in tidal lock. The indefatigable Dr. Baldwin keeps a close eye on the latest exoplanet research, somehow balancing his astronomical scholarship with a career as consultant psychiatrist at the 5 Boroughs Partnership NHS Trust (Warrington, UK). Read on to learn a great deal about where current thinking stands on a subject critical to the question of red dwarf habitability.

by Ashley Baldwin

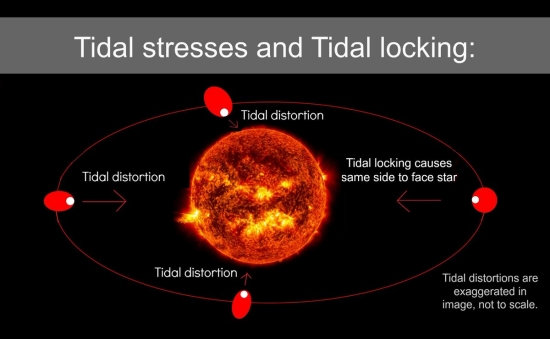

“Tidal locking”, “captured rotation” or “spin-orbit locking” etc occurs in most recognised guise when an orbiting astronomical body (be it a moon, planet or even a star) always presents the same face towards the object it is orbiting. In this instance, the orbit of the “satellite” body can be referred to as “synchronous”, whereby the tidally locked body takes as long to rotate around its own axis as to orbit its partner. This occurs due to the primary body’s gravity flexing the orbiting body into an elongated “prolate” shape. This in turn is then exposed to varying gravitational interaction with the central body.

Figure 1: Tidal stresses and tidal locking

As the “orbiter” rotates, its now elongated axis falls out of line with the central mass, which consequently perturbs it as it rotates across its orbit. It thus becomes subject to gravitationally induced torques that can act as a brake — through energy exchange and dissipation, the latter via friction-induced heat loss in the perturbed orbiting body. As M dwarf habitable zones are closer to their central star and their gravitational influence thus greater, it’s easy to see how this dissipated heat can contribute substantially to an exoplanet’s overall energy flux and can even affect its habitability potential – possibly tipping it into a runaway greenhouse scenario. (Kopparapu 2013).

Over millions of years (or more) this process can lead to “orbital synchronisation”. This arises when the orbiting body reaches a state where there is no longer any net exchange of rotation during the course of a completed orbit (Barnes 2010). Leaving a tidal locking state would only be possible with the addition of energy to the system. This might occur should some other massive object (such as a planet, or a star in, say, a binary system) break the equilibrium. If the masses of the two bodies (for instance Pluto & Charon) are similar, they can become tidally locked to each other.

Not all tidal locking involves synchronisation. “Super-synchronisation” occurs where an orbiting body becomes tidally locked to its parent body but rotates at a fixed but quicker rate. A topical example of this is the erstwhile “geosynchronous transfer orbit” (GTO). We see this on launcher specs all the time: “Payload to GTO”. This orbit is external to geosynchronous orbit, where many satellites start their operational lives, but allows for pre-orbital insertion inclination changes — economically expending less propellant prior to final insertion. Alternatively, such orbits can be used as dumping grounds for non-functioning satellites or related debris, so-called “geo-graveyard belts” (Luu 1998). Simulations suggest many exoplanets could exist in variants of such orbital types.

Gravitational interaction with a central star leads to progressive rotational slowing of a smaller planetary body like Mercury via energy exchange and heat dissipation. This is due to subtle but important tidal force variations across the orbiting body (remembering that gravity is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between any two bodies — thus “gravitational gradients” exist across solid bodies, leading to bulges). However, if the initial planetary orbit is significantly eccentric, this effect varies substantially across the orbital period (especially at periapsis — the point of strongest gravitational interaction) and can instead result in a spin-orbit resonance. In Mercury’s case, this is 3:2 (three rotations per two orbits) but other ratios can occur from 2:1 through 5:2 (Mahoney 2013). It’s worth noting that this effect is most pronounced for closer-in planets where the gravitational effects are greatest, so the effect should be even more relevant for the tightly packed exoplanetary architectures (e.g. TRAPPIST-1) that seem to be prevalent.

In extreme cases where the orbiting body’s orbit is nearly circular AND has a minimal or zero axial tilt — such as with the Moon — then the same hemisphere (libration allowing) faces the primary mass.

That said, for simplicity we will now assume that a smaller mass body (exoplanet) is orbiting a very much more massive body (star) — this is the focus of this review, with an unavoidable nod towards habitability.

For reasons of brevity and also pertaining to the exoplanet subject matter of recent posts, we will limit ourselves to the specific case of terrestrial exoplanets and their orbits around smaller main sequence stars.

The time to tidal locking can even be described by the adapted equation :

Tlock ≈ wa6 (0.4 m*R2) / (3 Gmp2 kR5) (Goldreich, Goldreich & Soter 1966); (Peale 1977); (Gladman 1996); (Greenberg 2009)

Where Tlock is “time to tidal locking”, w and k are constants which can be ignored for simplicity, m* is mass of the star, mp is mass of the planet, R is the exoplanet radius and “G” is Newton’s all important gravitational constant.

Tlock is substantially lengthened by “a” — increasing planetary semi-major axis (to the sixth power!). Tidal locking time is also increased by 0.4 X m* in this equation. However it is important to remember the context and just how massive a star, indeed ANY star, is — even an M dwarf star — many times, orders of magnitude even, more massive than a planet. A star thus plays the major role in the tidal locking of its attendant planets.

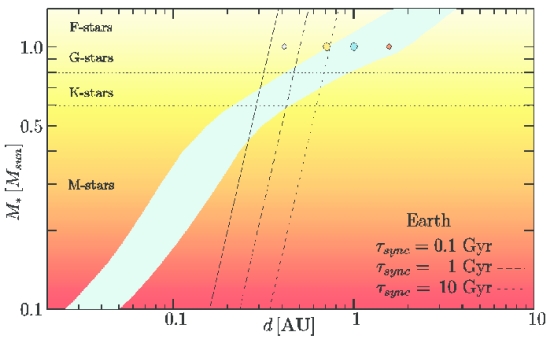

The gravitational constant G ensures that increasing stellar mass will substantially decrease Tlock. All other things being equal, increasing stellar mass is a major factor in reducing time to tidal locking.

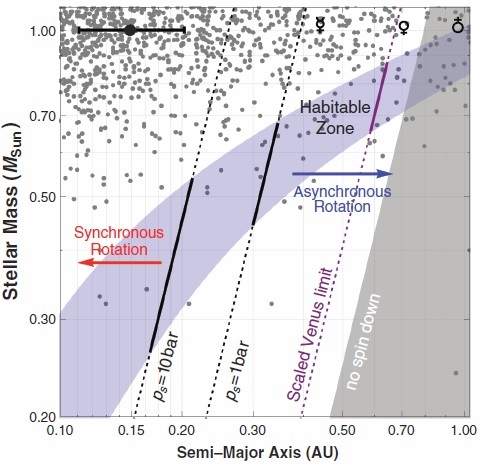

Figure 2: Stellar mass & type versus semi-major axis orange / red graph with superimposed Tsync for 0.1,1 and 10 gigayear times for an Earth mass planet. (Penz 2005)

The concept of synchronisation is relatively new, dating back to Stephen Dole’s seminal Habitable Planets for Man at the beginning of the space age in the early 1960s. The concept was purely theoretical, with somewhat arbitrary parameters at this point, but it implied that tidal lock would be a major impediment to the human-friendly “habitable” exoplanets Dole had in mind for his book. It was here that tidally locked orbits and planets in M-dwarf systems were first linked, in a negative way that to some extent still exists today (before we even get to coronal mass ejections, EUV and stellar flares et al !) Atmospheric collapse due to freezing out on the side of the planet facing away from the star is not the least of these problems.

It was only in 1993 that Kasting et al employed sophisticated 1-D climate modelling as part of describing what constituted habitable planets. Habitable planets essentially now meant planets with conditions that could sustain liquid water on their surfaces. This is a rather lower bar than that set by Dole thirty years earlier, but far more applicable and still a pillar of exoplanet science today. More importantly, Kasting’s team also simulated star/planet gravitational interaction.

They did this by utilising the “Equilibrium Tide” model (ET). Refined variants of this have now become THE staple of all subsequent related studies, as it too has “evolved”. The model essentially assumes that the gravitational force of the tide-raiser (star) produces an elongated shape in the perturbed body (exoplanet) and that its long axis is slightly misaligned with respect to an imaginary line connecting the two centres of mass.

The misalignment is crucial and is due to the dissipating processes within the “deformed” exoplanet, leading to evolution of the orbit and spin angular moments. From this, various equations can be created which map out the orbital and rotational evolutionary history of exoplanets over time (see above). ET was originally derived from the Earth/Moon system by Darwin in 1880 before refinement by Pearle in 1977. Iterations vary in subtle but significant ways and are used as the basis for increasingly sophisticated simulations as computing power increases. Barnes 2017 has carried out a detailed review of synchronising and ET modelling (see below).

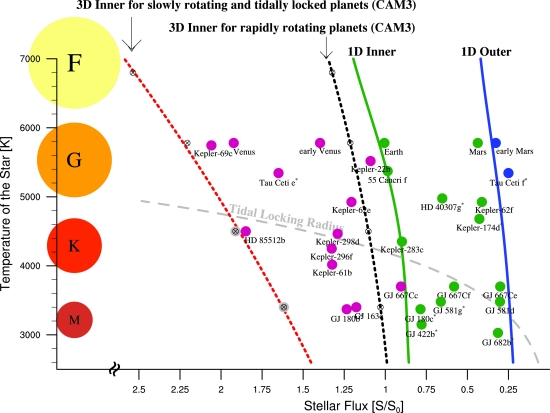

Kasting et al showed synchronisation of putative exoplanets orbiting in the habitable zones of M-dwarfs, stars with a mass of up to 0.42 Msun, within 4.5 billion years. They introduced the now familiar term “tidal locking radius”. Though a big step forward, this had the unfortunate consequence of continuing to propagate a pessimistic view of habitable exoplanets orbiting such stars. Importantly, stellar mass was still viewed as the major if not sole cause of synchronisation. The graph below (from Yang et al 2014), though based on sophisticated modelling, still captures this type of thinking. Here various habitable zone model ranges are superimposed on a graph of relative stellar insolation (and star type) versus semi-major axis examples of known exoplanets, adding realistic perspective. You will note also that for a 0.42 Msun star, with a temperature around 3500 K, the 1-D inner habitable range is very close to the value attributed to recently discovered TOI 700d — mid-80s percent.

Figure 3: Temperature of star versus stellar flux graph with superimposed coloured star classes and dashed gray “tidal locking radius” line.

The effects of other factors — such as starting orbital eccentricity (already encountered above with Mercury), baseline rotation rate, the presence of companion bodies (Greenberg, Corriea 2013) thermal tides arising from atmospheres (Leconte et al 2015), and stellar and planetary interiors (Driscoll & Barnes 2015), orbital tilt (Barnes 2017) — were not considered. As can be seen, it has only been over the last five years or so that these things have been added to simulations. Indeed, the results of these studies very much alter the whole tidal locking paradigm with particular relevance to habitable zones, which despite refinement (Kopparapu 2013, Selsis 2007) have only changed slightly, a big compliment to Kasting’s work in 1993.

Taken altogether, habitable zone planets of M,K and G stars all have the potential to become tidally locked. Not just M dwarfs — though their potential remains very much the greatest and especially for < 0.1 Msun stars such as TRAPPIST-1. Even the Earth, had its starting rotation been greater than just three days, according to Barnes 2017, might have become synchronous.

For the sake of brevity, this review has largely focused on stellar mass as a major driver in exoplanetary synchronisation. As can be seen above, as knowledge in this area progresses, other processes come into account. It is also becoming increasingly difficult to tease these out from drivers of exoplanetary habitability. So to this end we must look in more detail at some of the factors named above.

The planet Venus is unusual in many ways, but one in particular stands out: its retrograde and slow rotation rate that is longer than its orbital period. Why? What makes Venus different? One factor is that it is a rocky planet with a substantial atmosphere (92 bar at its surface). We all know about the infamous runaway greenhouse effect this drives, making Venus the hottest planet in the Solar System despite being further from the Sun than (spin/orbit resonant) Mercury. However, does this atmosphere have any other effects?

On Earth, the day/night cycle leads to variations in heat distribution in the atmosphere. It is known that the hottest time of day on Earth does not occur when the Sun is at its zenith and thus nearest to the Earth, but rather several hours later. This is because of thermal inertia. There is a delay between solar heating and thermal response, leading to mass redistribution. As the atmosphere and the Earth’s surface are generally well linked via friction, this will give rise to non-negligible thermal torques.

These torques are akin to the torques arising from the Sun’s uneven gravitational interaction with the Earth described above, though not as potent. On the Earth with its extended 1 AU orbit, they are largely inconsequential, but for 0.3 AU nearer Venus, they become significant. Depending on their direction, they can either slow up OR speed up planetary rotation, but either way they help to resist synchronisation. Over time, torques arising in Venus have acted to slow down its rotation, so much so that it has reversed to the retrograde pattern we see today.

So if this is true of Venus, how about exoplanets? Can these atmospheric torques resist or at least delay synchronisation and tidal locking in vulnerable areas around a star? This has been extensively modelled by Leconte et al 2015 and the answer was a resounding yes, especially for smaller, less luminous stars with close-in habitable zones, and not just for exoplanets with 90 bar atmospheres, either. Even 1 bar Earth-like atmospheres could help resist synchronisation for the habitable zones in stars of 0.5 Mearth – 0.7 Mearth.

Ten bar atmospheres were simulated and shown to resist synchronisation even for habitable zone planets orbiting 0.3 Mearth stars (mid-M dwarfs). These are the high bar “maximum greenhouse” CO2 atmospheres that are postulated to occur in the outer regions of stellar habitable zones. But there are limits. Venus’ 92 bar atmosphere is ironically so thick that most of the incident sunlight that isn’t reflected back into space is either absorbed or scattered before it can reach the planetary surface and exert the driving effect of thermal torques (Leconte et al 2015).

Figure 4: Red arrow synchronous rotation / blue arrow asynchronous rotation graph (Leconte 2015).

Orbital synchronisation and exoplanet habitability remains a contentious theoretical field that is subject to continual debate and constant change. Modern Global Climate Modelling (GCM) has become a sophisticated sub-science. Using an earlier iteration of GCM, Yang et al showed in 2013 that synchronised M-dwarf habitable zone planets would form thick cloud banks above their sub-stellar point. This would then reflect much of the incident stellar flux, thus reducing the energy reaching the surface. In turn, this would reduce the overall energy reaching the planet and so reduce global temperatures. The net effect in theory is to extend the stellar habitable zone inwards. However, the same author collaborated with Wolf and Kopparapu in 2016 to apply an updated 3-D model to the same problem. This showed that a sub-stellar cloud bank could not form, or would form and then move, a result effectively rebutting the 2013 findings and moving the habitable zone back to its original pre 2013 starting point. Expect more of this !

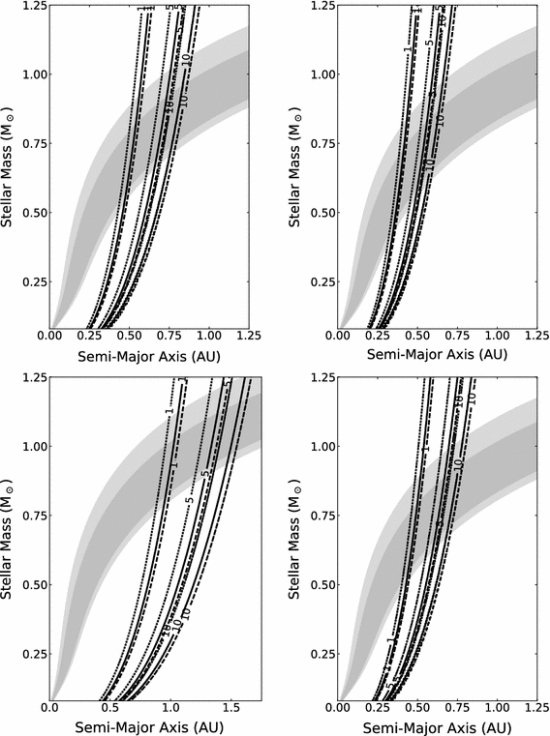

So, all things considered, just how easy is it for an exoplanet to become tidally locked and just how easy can habitable zone planets become tidally locked ? Barnes 2017 attempted to address just this question for exoplanets in circular orbits. He applied two well recognised refined variants (CPL left, CTL right in the graphic below) of the ET to two model populations of exoplanets orbiting differing stellar masses, and ran thousands of giga-year simulations for each (think of the computing power and time!) One population had a starting orbital period of 8 hours and an orbital tilt of 60°. The other had a starting period of ten days and a tilt of 0°. This produced the four outcomes illustrated below. The superimposed grey shading represents the latest habitable zones (Kopparapu 2013) iteration, with the dark grey representing the “conservative” and the light the “optimistic”.

Figure 5: “Four in one” black and white stellar mass vs semi-major axis / superimposed greyscale habzone graphs.

These results are indicative and significantly different from the status quo, which is that tidal locking is only something that applies to exoplanets orbiting in close to M dwarf and smaller K dwarf stars. For one thing, even this older paradigm implies that at least some “Goldilocks” stars are not quite as homely as expected (more Kasting than Dole). The Barnes work hints at potential overlap of the habitable zone for potentially a large fraction of K-class and even many G-class stars, driven by factors beyond simple stellar mass. Clearly planets with a slow initial rotation rate and low orbital tilt are at greater risk, as may prove the case. Opposed to this are non-synchronising factors such as, inter alia, higher baseline orbital eccentricities and the close proximity of other orbiting bodies (moons, planets …thinking TRAPPIST-1 and binary stars/brown dwarfs, as with the recently described Gliese 229Ac system).

What this also shows is the inextricable link between orbital features and planet habitability. No more so demonstrated than by Kepler, and likely even more so with its greater number of short orbital period planets, with any potential habitable zone planetary candidates lying within just tenths or less of an AU from their parent star. This is very much in the “red arrow” synchronous zone in the Leconte graphic above.

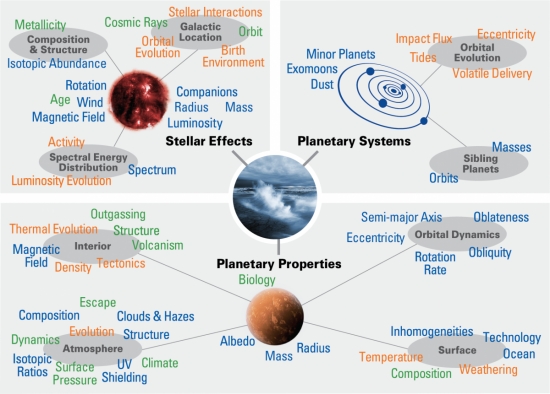

There are now over 4000 known exoplanets. The current focus is on their “characterisation” and this is largely about atmospheres and biosignatures. However, it is obvious that we need to know far more about their evolving and historical orbital properties. This is a part of a process of determining habitable planets/zones, which are about so much more than stellar mass.

Most of the exoplanets discovered already by Kepler et al orbit close in to their stars, including those few in the potential tidal lock habitable zone. Ongoing Doppler photometry and TESS will identify thousands more such exoplanets, many of which will be even closer to their latest star given TESS’ shorter 27 day observation runs. TOI 700d and Gliese 229Ac are just for starters. Hopefully the search for habitability will expand to encompass the unavoidable connexion with planetary orbital features.

Know the star to know the planet, but know the orbit to know them both.

Figure 6: Stellar effects/planetary properties/planetary systems (Meadows and Barnes 2018)

References

Barnes,R. Formation and evolution of exoplanets. John Wiley & Sons, p248, 2010

Barnes, R. Tidal locking of habitable exoplanets. Celestial mechanics and dynamical astronomy Vol 129, Issue 4, pp 509-536, Dec 2017

Darwin, G H. On the secular changes in the elements of the orbit of a satellite revolving about a tidally distorted planet. Royal Society of London Philosophical Transactions, Series I, 171:713-891 ; 1880.

Dole, S H. Habitable Planets for Man. 1964

Goldreich, P. Final spin rates of planets and satellites. Astronomical Journal, 71, 1966

Goldreich, P., Soter, A., Q in the solar system. Icarus 5, 375-389, 1966

Gladman, B et al. Synchronous locking of tidally evolving satellites. Icarus 133 (1) 166-192, 1996

Greenberg, R. Frequency dependence of tidal Q, The Astrophysical Journal, 698, L42-45, 2009

Kasting, J. F. Habitable zones around main sequence stars. Icarus,101 d 108-128 Jan 1993

Kopparapu, R K et al. Habitable zones around main sequence stars: New Estimates. The Astrophysical Journal, 765;131, March 2013

Kopparapu R K, Wolf E, Yang et al. The inner edge of the habitable zone for synchronously rotating planets around low-mass stars using general circulation models. The Astrophysical Journal Volume 819, Number 1, March 2016

Luu, K. Effects of perturbations on space debris in super-synchronous storage orbits. Air Force Research Laboratory Technical Reports, 1998

Mahoney,T J. Mercury. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013

Meadows V S, Barnes R K. Factors affecting exoplanet habitability. In Handbook of Exoplanets P57, 2018

Peale, S J. Rotation histories of natural satellites. Burns, J A, Editor, IAU Colloquium 28; Planetary Satellites, p 87-111, 1977

Penz,T et al. Constraints for the evolution of habitable planets: Implications for the search of life in the Universe: Evolution of Habitable planets, 2005

Yang, J et al. Stabilising cloud feedback dramatically expands the habitable zone of tidally locked planets. The Astrophysical Journal Letters: 771:L45, July 2013

Yang, J et al. Strong dependence of the inner edge of the habitable zone on planetary rotation rate. The Astrophysical Journal Letters: 787:1, April 2014