Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Lunar Recession: Implications for the Early Earth

It was in 1775 that Pierre-Simon Laplace developed his theories of tidal dynamics, formulating in the following year a set of equations to explain the phenomenon at a greater level of detail than ever before. Looking at the Moon on a frosty winter night, it’s pleasing to realize that there is a mountainous region at the end of Montes Jura in Mare Imbrium that is called Promontorium Laplace. Surely the French astronomer and mathematician would have been pleased.

One result of Laplace’s calculations was his pointing out that the Moon’s equatorial bulge was far too large to be accounted for by its current rate of rotation. Here we’re dealing with conditions of formation of an object thought to have been the result of a collision between the Earth and a Mars-sized planet early in our system’s evolution. I seldom write about the Moon in these pages, but today’s story on its development catches my eye because it relates to the early history of our own world and the Solar System itself. For Chuan Qin (now at Harvard University) and colleagues have modeled how quickly the hot young Moon receded from the Earth.

The current rate of the Moon’s recession from the Earth is about 4 centimeters per year. But what was the recession rate in the earliest periods of its formation?

Image credit: University of Colorado at Boulder.

The tidal bulge at the equator evidently has much to tell us. A hot, fast-rotating early Moon would have possessed a much larger equatorial bulge than today’s. As the Moon moved farther from the Earth and its rotation slowed, the bulge would have shrunk until, cooled and hardened, a permanent ‘fossil’ bulge remained in its crust. Working with a model adjusting the relative timing of lithosphere thickening and lunar orbit recession, Qin and team have found that the pace of the lunar recession was slow, lasting for several hundred million years in an era roughly four billion years ago.

If this dynamic modeling is correct, it can tell us something about the early Earth, says Shijie Zhong (University of Colorado at Boulder), a co-author on the paper:

“The moon’s fossil bulge may contain secrets of Earth’s early evolution that were not recorded anywhere else. Our model captures two time-dependent processes and this is the first time that anyone has been able to put timescale constraints on early lunar recession.”

The new model has implications for the hydrosphere, the combined mass of water on the early Earth. The researchers argue that the Moon’s equatorial bulge is evidence that Earth’s energy dissipation in response to tidal forces would have been greatly reduced in this period. That’s assuming that a hydrosphere even existed in the Hadean, a geologic eon that began with the planet’s formation some 4.6 billion years ago and ended roughly 4 billion years ago. From the paper:

Viable solutions indicate that lunar bulge formation was a geologically slow process lasting several hundred million years, that the process was complete about 4 Ga when the Moon-Earth distance was less than ~32 Earth radii, and that the Earth in Hadean was significantly less dissipative to lunar tides than during the last 4 Gyr, possibly implying a frozen hydrosphere due to the fainter young Sun.

The paper makes the case that Earth’s hydrosphere may have been frozen during the time of the Moon’s formation, making for little tidal dissipation. One possibility emerging from that is a faint young Sun radiating about 30 percent less energy than today. A ‘snowball Earth’ in the Hadean could have been the result, but we have no direct evidence in the geological record for this. Qin and team intend to continue work on their model as they dig deeper into the Moon’s evolution in a period ending with the Late Heavy Bombardment some 3.8 billion years ago.

The paper is Qin et al., “Formation of the Lunar Fossil Bulges and Its Implication for the Early Earth and Moon,” Geophysical Research Letters 2 February 2018 (abstract).

TRAPPIST-1: Planets Likely Rich in Volatiles

Yesterday we saw that, by pushing the Hubble telescope to its limits, we could make a call about three of the TRAPPIST-1 planets — d, e and f — and one possibility for their respective atmospheres. The Hubble data rule out puffy atmospheres rich in hydrogen for these three (TRAPPIST-1 g needs more work before a definitive call can be made there).

This is a useful finding, for hydrogen is a greenhouse gas that can heat planets close to their star beyond our usual norms for habitability. Set out deeper in a stellar system, we can think of Neptune, a gaseous world far different from the kind of rocky, terrestrial-class planets most likely to produce surface water. So on balance, the Hubble work, while not telling us anything more about potential atmospheres in this system, does rule out the Neptune scenario. That leaves open the question of whether future instruments will find more compact atmospheres.

The James Webb Space Telescope should be able to probe these worlds, perhaps revealing heavier gases like methane, carbon dioxide, water and oxygen. Meanwhile, we have another new paper to look at, from lead author Simon Grimm and colleagues, taking another angle on the composition of the TRAPPIST-1 worlds. Grimm (University of Bern Centre for Space and Habitability) and team have produced new mass estimates that allow a more fine-grained appraisal of the planets’ density, which is a step toward characterizing each planet.

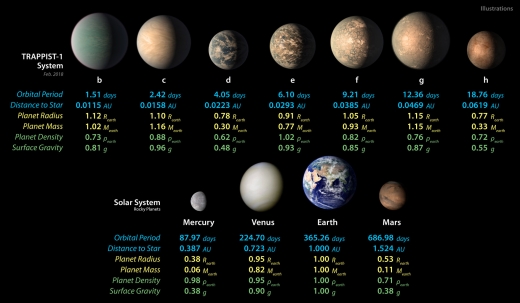

Image: This chart shows, on the top row, artist concepts of the seven planets of TRAPPIST-1 with their orbital periods, distances from their star, radii, masses, densities and surface gravity as compared to those of Earth. These numbers are current as of February 2018. On the bottom row, the same numbers are displayed for the bodies of our inner solar system: Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. The TRAPPIST-1 planets orbit their star extremely closely, with periods ranging from 1.5 to only about 20 days. This is much shorter than the period of Mercury, which orbits our sun in about 88 days. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

The work of Grimm and team is yet another illustration of why TRAPPIST-1 is such a remarkable target. A transit can tell us about the radius of the world between us and the star, but we also need mass information to make a call on density. Calling this system “…a fascinating setting to study the formation and evolution of tightly-packed small planet systems…” the paper explains the problem in a nutshell:

While the TRAPPIST-1 planet sizes are all known to better than 5%, their densities suffer from significant uncertainty (between 28 and 95%) because of loose constraints on planet masses. This critically impacts in turn our knowledge of the planetary interiors, formation pathway (Ormel et al. 2017; Unterborn et al. 2017) and long-term stability of the system. So far, most exoplanet masses have been measured using the radial-velocity technique. But because of the TRAPPIST-1 faintness (V=19), precise constraints on Earth-mass planets are beyond the reach of existing spectrographs.

Fortunately, in this system we are dealing with seven tightly packed planets (all within the orbit of Mercury around the Sun). In this resonant chain, more massive planets can perturb the orbits of lighter ones, creating transit timing variations (TTV) that can be modeled to produce mass values for each world. 284 transit timing variations obtained with the SPECULOOS and TRAPPIST instruments between September 17, 2015 and March 27, 2017 were complemented by previously published TRAPPIST data and Spitzer as well as Kepler (K2) observations.

The models employed are anything but simple. In fact, the researchers had to examine 35 different parameters, a problem they tackled with new computer algorithms. Simulating orbits until the calculations agree with observed values for the TRAPPIST-1 transits tightens up our previous mass estimates. The work absorbed a year, says Grimm, who goes on to explain:

“The TRAPPIST-1 planets are so close together that they interfere with each other gravitationally, so the times when they pass in front of the star shift slightly. These shifts depend on the planets’ masses, their distances and other orbital parameters. With a computer model, we simulate the planets’ orbits until the calculated transits agree with the observed values, and hence derive the planetary masses.”

What emerges corroborates what the Hubble data show. Rather than being gaseous worlds, the TRAPPIST-1 planets are primarily made of rock. Moreover, they contain significant amounts of volatiles, probably water, given that water in the form of vapor, liquid or ice is the most abundant source of volatiles for the kind of protoplanetary disk that would have produced this system. In some cases, the water can amount to 5% of the planet’s mass. By contrast, Earth has only about 0.02% water by mass. Some of the TRAPPIST-1 planets could thus have 250 times more water than the Earth’s oceans.

TRAPPIST-1 b and c, the two innermost planets, appear to have rocky cores and thick atmospheres, according to this work, while TRAPPIST-1 d, the lightest of the planets (about 30 percent Earth mass) may have a large atmosphere, an ocean or an ice layer. All three possibilities would account for the volume of volatiles thought to match a planet of this density.

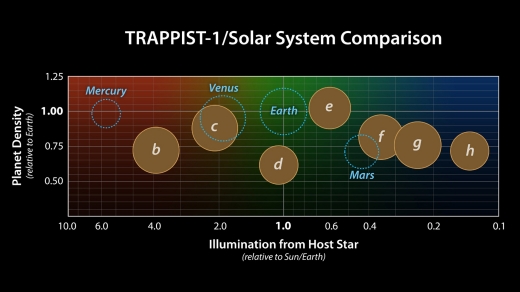

TRAPPIST-1 e turns out to be somewhat denser than the Earth, suggestive of a dense iron core and, perhaps, the absence of a thick atmosphere, ocean or ice layer. In terms of insolation from the central star, as well as size and density, this is the planet most like the Earth. The question of why it seems to have a rockier composition than any of its companions remains unresolved.

As to the outer worlds, TRAPPIST-1 f, g and h are distant enough for ice to be frozen on their surfaces, and according to Grimm’s team, are unlikely to have any more than thin atmospheres.

Image: This graph presents known properties of the seven TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets (labeled b through h), showing how they stack up to the inner rocky worlds in our own solar system. The horizontal axis shows the level of illumination that each planet receives from its host star. TRAPPIST-1 is a mere 9 percent the mass of our Sun, and its temperature is much cooler. But because the TRAPPIST-1 planets orbit so closely to their star, they receive comparable levels of light and heat to Earth and its neighboring planets. The vertical axis shows the densities of the planets. Density, calculated based on a planet’s mass and volume, is the first important step in understanding a planet’s composition. The plot shows that the TRAPPIST-1 planet densities range from being similar to Earth and Venus at the upper end, down to values comparable to Mars at the lower end. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Among the most interesting things about TRAPPIST-1 is the history of its planetary system, which the paper addresses this way:

The resonant structure of the TRAPPIST-1 system (Luger et al. 2017) is a telltale sign of orbital migration (Terquem & Papaloizou 2007; Ogihara & Ida 2009). The fact that all seven planets form a single resonant chain indicates that the entire system migrated in concert (Cossou et al. 2014; Izidoro et al. 2017). Indeed, orbital solutions generated by disk-driven migration have been shown to be more stable than other solutions (Tamayo et al. 2017b). Whereas most resonant systems are likely to be unstable ((Izidoro et al. 2017; Matsumoto et al. 2012)), the TRAPPIST-1 can be interpreted as a system that underwent a relatively slow migration creating a long-lived resonant system.

We will need the James Webb Space Telescope to move to greater certainty on the question of whether atmospheres actually exist here and what they are made of. I notice that the robotic SAINT-EX Observatory is under construction in Mexico, with the goal of searching for terrestrial planets around cool stars like TRAPPIST-1 (it will also provide ground support for the European Space Agency’s CHEOPS mission). Demory and team hope to apply the computer code they used in the TRAPPIST-1 work on systems detected by SAINT-EX, which should begin operations this year.

The paper is Grimm et al., “The nature of the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets,” in press at Astronomy & Astrophysics (preprint).

Falcon Heavy: Extraordinary!

The Tau Zero Foundation and Centauri Dreams congratulates team Space Exploration Technologies, for the successful, historic, pioneering test flight of the Falcon Heavy.

Ad Astra Incrementis indeed!

From all of us,

Jeff Greason

Marc Millis

Rhonda Stevenson

Andrew Aldrin

Paul Gilster

Bill Tauskey

Rod Pyle

Probing TRAPPIST-1 Planetary Atmospheres

This week offers two interesting papers about the TRAPPIST-1 planets, one from Hubble data looking at the question of hydrogen in potential planetary atmospheres, the other drawing on data from the European Southern Observatory’s Paranal facility as well as the Spitzer and Kepler space-based instruments. We’ll look at the Hubble work this morning and move on to the second paper tomorrow. Both offer meaty stuff to dig into, for we’re beginning to characterize these seven planets, which form a unique laboratory for the study of red dwarf systems.

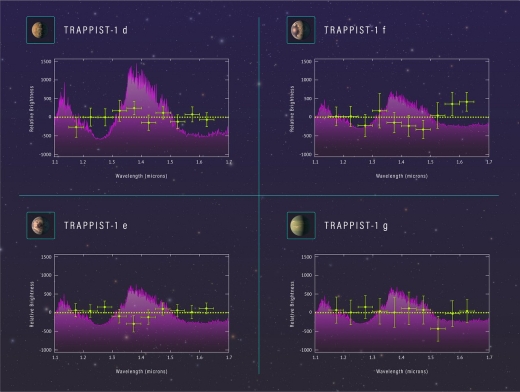

Published in Nature Astronomy, the Hubble results screen four of the TRAPPIST-1 planets — d, e, f and g — to study their potential atmospheres in the infrared, using Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 in data collected from December 2016 to January 2017. The data allow us to rule out a cloud-free hydrogen-rich atmosphere on three of these worlds, while TRAPPIST-1g needs further observation before a hydrogen atmosphere can be conclusively excluded.

Image: These spectra show the chemical makeup of the atmospheres of four Earth-size planets orbiting within or near the habitable zone of the nearby star TRAPPIST-1. The habitable zone is a region at a distance from the star where liquid water, the key to life as we know it, could exist on the planets’ surfaces. To obtain the spectra, astronomers used the Hubble Space Telescope to collect light from TRAPPIST-1 that passed through the exoplanets’ atmospheres as the alien worlds crossed the face of the star. Credit: NASA, ESA, and Z. Levy (STScI).

Pay particular attention to the purple curves in the above image. These show the signature we would expect to see from gases like water and methane, which would be found if any of these planets had a hydrogen-dominated atmosphere like Neptune’s. The spectroscopic signature should be strong in the near-infrared. The Hubble results are indicated by the green crosses, clearly showing no evidence of such an extended atmosphere for TRAPPIST-1 d, f and e.

Julien de Wit (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), lead author on the paper, explains the significance of the finding:

“The presence of puffy, hydrogen-dominated atmospheres would have indicated that these planets are more likely gaseous worlds like Neptune. The lack of hydrogen in their atmospheres further supports theories about the planets being terrestrial in nature. This discovery is an important step towards determining if the planets might harbour liquid water on their surfaces, which could enable them to support living organisms.”

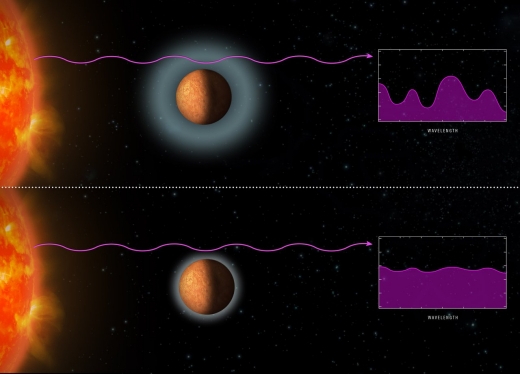

The work proceeded through transmission spectroscopy, in which some of the light of the star passes through the planetary atmosphere and leaves a distinctive trace in the star’s spectrum. The beauty of the TRAPPIST-1 system is that we have so many transits to work with. Moreover, all seven of the planets orbit their star much closer than Mercury is to the Sun, so we have transits occurring frequently, and the possibility of liquid water on some planetary surfaces. We’re also dealing with a planetary system that’s a relatively nearby 40 light years away.

Image: The graphic at the top shows a model spectrum containing the signatures of gases that the astronomers would expect to see if the exoplanets’ atmospheres were puffy and dominated by primordial hydrogen from the distant worlds’ formation. The Hubble observations, however, revealed that the planets do not have hydrogen-dominated atmospheres. The flatter spectrum shown in the lower illustration indicates that Hubble did not spot any traces of water or methane, which are abundant in hydrogen-rich atmospheres. The researchers concluded that the atmospheres are composed of heavier elements residing at much lower altitudes than could be measured by the Hubble observations. Credit: NASA, ESA and Z. Levy (STScI).

If heavier gases like carbon dioxide, methane, water and oxygen are atmospheric constituents in this system, the James Webb Space Telescope may well be able to find them. What the Hubble work achieves is to take one possibility off the table before JWST goes to work, assuming the latter is successfully deployed in 2019.

The TRAPPIST-1 planets may have had hydrogen atmospheres when first formed, assuming they formed further away from the parent star and migrated into their present positions. The primordial hydrogen would then have been lost as the planets moved close to the star, allowing the formation of secondary atmospheres. Our own Solar System’s rocky planets evidently formed in hotter and drier regions much closer, on a relative basis, to the Sun.

Hannah Wakeford (STScI), one of the scientists involved with this work, adds:

“There are no analogs in our solar system for these planets. One of the things researchers are finding is that many of the more common exoplanets don’t have analogs in our solar system.”

The paper is de Wit et al., “Atmospheric reconnaissance of the habitable-zone Earth-sized planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1,” Nature Astronomy 5 February 2018 (abstract). Tomorrow we’ll look at work just published in Astronomy and Astrophysics on new constraints on the mass, density and composition of the seven planets around TRAPPIST-1.

Detection of Extragalactic Planets?

I was pleased to be a guest on David Livingston’s The Space Show last week. David’s questions are always well chosen, as were those of the listeners who participated in the show, and we spoke broadly about the interstellar effort and what it will take to eventually get human technologies to the stars. The show is now available in David’s archives.

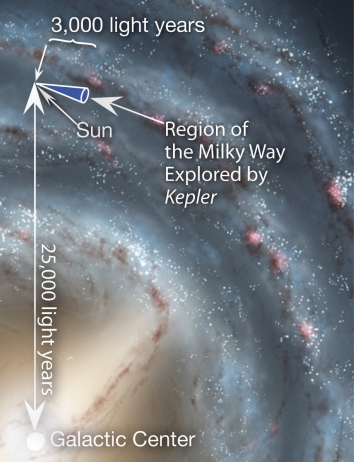

I suspect that if David and I had spoken a couple of days later, the topic would have gotten around to gravitational microlensing, and specifically, the news about planets in other galaxies. On the surface, the story seems sensational. In our own galaxy, we can use radial velocity and transit studies on stars, but here our working distances are constrained by our method. The original Kepler field of view in Cygnus, Lyra and Draco, for example, contained stars ranging from 600 to 3000 light years out — get beyond 3000 light years and transits are not detectable.

Image: The Sun is about 25,000 light years from the center of the galaxy, about half the distance from the center to the edge. The blue cone shows the region of the Milky Way that Kepler explored for planets. Kepler looked along a spiral arm of our galaxy. The distance to most of the stars for which Earth-size planets can be detected by Kepler is from 600 to 3,000 light years. Less than 1% of these stars in the region are closer than 600 light years. Stars farther than 3,000 light years are too faint for Kepler to observe the transits needed to detect Earth-size planets. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (SSC).

Gravitational microlensing, in which a star moves in front of a more distant star so that light from the background object is distorted by the foreground star’s gravitational field, can turn up distant planets within our own galaxy. In fact, it’s quite a useful tool because it is not limited by line of sight — no planet needs to transit — and is not dependent on the planet’s distance from its star.

Microlensing has allowed us to find planets thousands of light years away, near the center of the Milky Way. We see the pattern of the microlensing event temporarily disrupted by a spike of brightness as the planet around the closer star causes its own gravitational disruption.

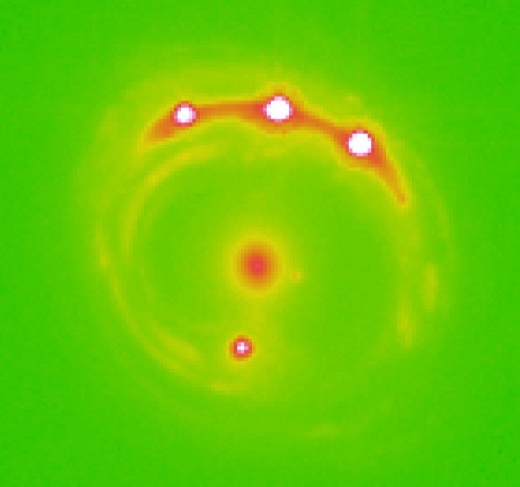

But how do we hope to find planets billions of light years away? At the University of Oklahoma, Xinyu Dai and Eduardo Guerras have tackled the question using data from the Chandra X-Ray Observatory, working with microlensing models calculated at the university’s Supercomputing Center for Education and Research. Their work revolved around the microlensing properties of a supermassive black hole at the center of quasar RX J1131-1231. The background quasar, about 6 billion light years away, is what is being lensed by the foreground galaxy, which is 3.8 billion light years out.

We are dealing with what is known as a quasar-galaxy strong lensing system, one in which a background quasar is being gravitationally lensed by a foreground galaxy. The result is that multiple images of the quasar form, as seen in the image below. The light from the background quasar crosses different locations in the foreground galaxy, and is lensed as well by nearby stars in the lens galaxy, an effect called quasar microlensing. The latter is a useful tool, for astronomers have used it to study accretion disks around supermassive black holes at the center of quasars. It can also provide information about the lensing galaxy itself.

Image: The gravitational lens RX J1131-1231 galaxy with the lens galaxy at the center and four lensed background quasar images. Credit: University of Oklahoma.

Let’s turn to the paper, where the relevance of this to extragalactic planets emerges:

As we probe smaller and smaller emission regions of the accretion disk close to the event horizon of the SMBH, the gravitational fields of planets in the lensing galaxy start to contribute to the overall gravitational lensing effect, providing us with an opportunity to probe planets in extragalactic galaxies…

The authors analyze the Einstein ring created by lensing effects to show that emissions close to the Schwarzschild radius of the central supermassive black hole of the source quasar will be affected by planets in the lensing galaxy. Thus we have a way of identifying a population of planets in another galaxy, though not planets orbiting a central star. For the paper goes on:

We have shown that quasar microlensing can probe planets, especially the unbound ones, in extragalactic galaxies, by studying the microlensing behavior of emission very close to the inner most stable circular orbit of the super-massive black hole of the source quasar. For bound planets, they contribute little to the overall magnification pattern in this study.

These planets would be, in other words, so-called ‘rogue’ planets not associated with any star, for bound planets of the kind we are used to studying with radial velocity and transit methods would be below the threshold of detection — they would not change the magnification patterns being observed.

The numbers on these rogue planets are impressive: Roughly 2000 objects per main sequence star in sizes ranging between the Moon and Jupiter — 200 of these per main sequence star would be in the Mars to Jupiter range.

These numbers, Dai and Guerras note, are consistent with theoretical studies showing a large population of unbound planets in our own galaxy. Stanford’s Louis Strigari and colleagues, for example, have found that there may be up to 105 compact objects per main sequence star in the Milky Way, using evidence from microlensing as well as direct imaging. Our galaxy may, in other words, be well populated with such objects, most of these relatively small but some larger than Jupiter. See Island Hopping to the Stars for more on Strigari’s work.

What to make of all this? Before this work, the only evidence for an extragalactic planet was the microlensing event PA-99-N2, detected in 1999, and consistent with a star in the disk of M31, the Andromeda galaxy, lensing a background red giant. A planet of 6 times Jupiter’s mass is one explanation for the lensing profile, but there is no way to confirm the possible planet.

Now we have not the detection of individual planets but a hypothesis that lensing data of a galaxy 3.8 billion light years away can be explained by the presence of a population of unbound planets and other compact objects much smaller than planets. The idea that there would be planets in other galaxies is hardly unusual, given their numbers in our own Milky Way. But it’s an exciting thought that we can now begin to study extragalactic exoplanets, even if we’re extremely early in the process and there is much to be learned. As the paper notes:

It is possible that a population of distant but bound planets (Sumi et al. 2011) can contribute to a significant fraction of the planet population, which we defer to future investigations. Because of the much larger Einstein ring size for extragalactic microlensing, we expect that two models, the unbound and the distant but bound planets, can be better distinguished in the extragalactic regime.

The paper is Xinyu Dai & Eduardo Guerras, “Probing Planets in Extragalactic Galaxies Using Quasar Microlensing,” accepted at Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint). And if you’re interested in the PA-99-N2 event, one source is Ingrosso et al., “Detection of Exoplanets in M31 with Pixel-Lensing: The Event Pa-99-N2 Case,” Twelfth Marcel Grossmann Meeting: on Recent Developments in Theoretical and Experimental General Relativity. p. 2191 (preprint).

Gravitational Lensing: Untangling an Image

The behavior of distant galaxies may tell us much about our own Milky Way’s evolution, as well as alerting us to the differing outcomes possible as galaxies mature. This morning we look at a galaxy labeled eMACSJ1341-QG-1, one that puts on display the phenomenon of gravitational lensing. We may one day use the distortion of spacetime caused by massive objects much closer to home to study nearby stars and their planets, assuming we can learn to exploit the natural gravitational lensing effect that occurs at 550 AU from the Sun.

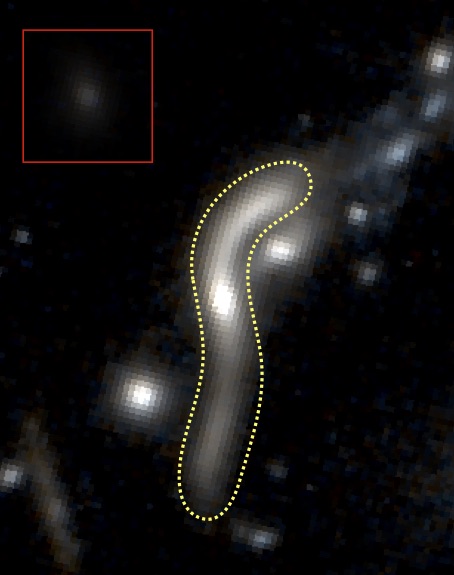

But back to the galactic perspective. Lined up with a massive galaxy cluster called eMACSJ1341.9-2441, the light from the much more distant galaxy is magnified by 30 times as the gravity of the intervening cluster — its presumed dark matter, gas and thousands of individual galaxies — distorts spacetime. Gravitational lensing was confirmed during a solar eclipse in 1919, when background stars were found to be offset in precisely the way Albert Einstein had predicted. Astronomers now rely on such lensing to produce information about objects that would otherwise be all but invisible.

Image: The quiescent galaxy eMACSJ1341-QG-1 as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope. The yellow dotted line traces the boundaries of the galaxy’s gravitationally lensed image. The inset on the upper left shows what eMACSJ1341-QG-1 would look like if we observed it directly, without the cluster lens. The dramatic amplification and distortion caused by the intervening, massive galaxy cluster (of which only a few galaxies are seen in this zoomed-in view) is apparent. Credit: Harald Ebeling, UH IfA.

Discovery of the quiescent galaxy, identified as a gravitationally lensed triple image, was confirmed by the ESO/X-Shooter spectrograph, mounted at the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope site at Cerro Paranal in Chile. Harald Ebeling (University of Hawaii, Honolulu), lead author of the paper on this work, describes the effort, which has now produced a new record for magnification of this type of galaxy:

“We specialize in finding extremely massive clusters that act as natural telescopes and have already discovered many exciting cases of gravitational lensing. This discovery stands out though, as the huge magnification provided by eMACSJ1341 allows us to study in detail a very rare type of galaxy.”

Quiescent galaxies — those in which star formation has all but ceased — represent the endpoint of galaxy evolution, which makes this one somewhat unusual. Objects at this redshift should be young enough not to have used up their gas supply. Hence learning why eMACSJ1341-QG-1 has stopped forming stars is a significant quest.

Working with data from the Hubble Space Telescope, Ebeling and colleagues now continue the study through HST imaging as well as ground-based instruments, and further analysis of the lens model that allows them to remove distortion from the magnified image. From the paper;

Although ground-based spectroscopy with facilities in Chile and on Maunakea will allow the characterization of the stellar populations of eMACSJ1341-QG-1, an analysis of its spatial profile and any radial dependencies of its properties relies on the availability of resolved colors and a robust lens model that allows the reconstruction of the galaxy in the source plane. HST imaging in multiple filters will be critically important to achieve either of these goals.

There is much to learn:

While it is widely accepted that already at z?1.5 a majority of the most massive galaxies had evolved stellar populations and form few stars, the observational evidence behind this picture is not conclusive, in particular regarding the puzzlingly compact size of some of these galaxies, the quenching mechanism, and the impact of dust on the apparent prominence of the old stellar population.

Centauri Dreams’ take: Fascinating in its own right, gravitational lensing studies like these remind us that when we do become capable of sending spacecraft to 550 AU and beyond to explore the uses of the Sun’s lens to study possible mission targets, we’re faced with huge questions of how to remove the massive distortion of the image, untangling it to produce workable information. The rapidly advancing field of deep-sky gravitational lensing should produce numerous insights into how we approach lensed images from future space missions.

Let me also note this: Gravitational focus lensing in the context of space missions was discussed by Geoff Landis (NASA GRC) as well as Slava Turyshev (JPL) at the most recent Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop. You can see the video of both presentations here.

The paper is Ebeling et al., “Thirty-fold: Extreme Gravitational Lensing of a Quiescent Galaxy at z = 1.6,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 852, No. 1 (abstract / preprint).