Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Deck Hands for a Four Decade Journey

?If you were offered a chance to make an interstellar journey, would you take it? How about a garden-variety trip to low-Earth orbit? I’m often asked questions like this when I make presentations to the public, and I have no hesitation in saying no. Though I’m no longer doing any flight instructing, I used to love flying airplanes, but getting into a rocket and being propelled anywhere is not for me. To each his own: I’m fascinated with deep space and hope many humans go there, and you can count on me to write about their missions and robotic ones as well while keeping my office right here on Earth.

The point is, the percentage of people who actually go out and take the incredible journeys and fly the dangerous missions is vanishingly low. But throughout history, there have always been a few intrepid souls who were willing to get into the canoes or the caravels or the biplanes and open up new territories and technologies. Thank God we have the Neil Armstrongs and Sergei Krikalyovs of this world. And somewhere in England there are the relatives of some young 18th Century adventurer who signed up as a cabin boy and wound up living out his life in Australia. People like this drive the species forward and put into action the yearning for exploration I suspect we all share.

Image: Sara Seager, who specializes in exoplanet atmospheres and interiors as the Ellen Swallow Richards Professor of Planetary Science at MIT. Credit: Justin Knight.

I’ve told this story before, but in the past few weeks a high percentage of the people coming to this site are coming for the first time, so I’ll tell it again. Robert Forward was the scientist who more than any other argued that we study methods for reaching the stars, saying that it could be done without violating the laws of physics and would therefore one day occur. Forward’s son Bob told me what happened one night at dinner when he asked his father whether he would get on a starship if it landed nearby and he was asked to go out and explore the universe, with the proviso that he could never come back. Forward’s response was instantaneous: “Of course!”

To which his wife Martha could only reply: “What about us? You mean you would just leave your family and disappear into the universe?” That made Forward pensive for only a moment as he replied, “You have to understand. This is what I have dreamed about all my life.”

MIT’s Sara Seager always manages to work the personal participation question into her talks on exoplanets. She pushes the audience this way and that and it always turns out that there are some people who would go no matter what. Here’s what she told The Atlantic’s Ross Andersen in a recent story, after describing how nuclear pulse propulsion or some kind of sail might conceivably get a spacecraft up to ten percent of lightspeed, which makes for a four-decade journey to the nearest stars:

“…I explain the hazards of living on a spacecraft for 40 years, the fact that life could be extremely tedious, and could possibly even include some kind of induced hibernation. But then I always ask if anyone in the audience would volunteer for a 40+ year journey, and every single time I get a show of hands. And then I say, “Oh I forgot to mention, it’s a one way trip,” and even then I get the same show of hands. This tells me that our drive to explore is so great that if and when engineers succeed at traveling at least 10 percent of the speed of light, there will be people willing to make the journey. It’s just a matter of time.”

I don’t doubt that Seager is right. What she might have gone on to say, if she really wanted to push the point, is that at ten percent of the speed of light, the Alpha Centauri mission that reaches its destination in 43 years is clearly a flyby. Spend more than four decades in transit and then whisk through the target system in less than a day. Would the hands still come up? My guess is that a few still would. A few would probably come up in answer to the question: “Would you go to Alpha Centauri if the only planet in the system turned out to be heat-blasted Centauri B b?” Explorers do this kind of thing — Percy Fawcett didn’t push into the Mato Grosso because he thought it was a clement place to be, nor did Robert Falcon Scott think highly of Antarctic weather.

Seager mentions what Marc Millis always calls the ‘incessant obsolescence’ problem, namely that sending one probe may simply result in its being passed enroute by another probe built later with faster technology. You can keep working that scenario until your head spins (go re-read A. E. van Vogt’s ‘Far Centaurus’ for just one science fictional take on the issue), but waiting for technology to improve gets you nowhere. At some point, you have to launch something, because we learn both through our successes and our failures, and waiting for things to happen can result in stagnation. Pushing the envelope with our crew of hand-raisers is what makes for progress.

Andersen is always a good interviewer, and he homes in on a key issue with regard to interstellar technologies. How do we develop them? Specifically, we would like to wed improved space science to the industries that can benefit from what a space infrastructure can produce, but what kind of industry would benefit from the technologies that can get us to the stars? Noting her belief that the first interstellar missions will be robotic probes, Seager responds:

Right now, I can’t see any connection between capabilities for interstellar travel and industry — at this point, it would purely be for exploration. But we can still benefit if industry decides a low-Earth orbit platform for assembly and launch would be useful. That’s because much of the fuel used for space missions is used to combat Earth’s gravity. If you have a way to assemble these probes in space, you actually have a chance to be more efficient and go faster. It’s conceivable that the private sector would be interested in something like that.

We’re going to be learning a lot more about what the private sector is and isn’t interested in as we experiment with different business models — Planetary Resources comes to mind (Seager serves as an advisor to the company), but ideas for turning a profit in space are hardly limited to asteroid mining. The suspicion here is that we will be unable to get a good read on commercial space interests until we’ve pushed that envelope as well, actually trying mission concepts and business models across a wide front to see what works. But surely Seager is right that low-Earth orbit is a key to the space infrastructure we want to build. Get there, as the saying goes, and you’re halfway to anywhere.

Centauri B: Targets and Possibilities

Voyager 1, now 17 light hours from Earth, continues to be my touchstone when asked about getting to Alpha Centauri — and in the last few days, I’ve been asked that question a lot. At 17.1 kilometers per second, Voyager 1 would need 74,000 years to reach the blistering orb we now believe to be orbiting Centauri B. Voyager 1 is not the fastest thing we’ve ever launched — New Horizons at one point in its mission was moving with greater velocity, though no longer, and the Helios II Solar probe, no longer functional, reaches about 70 kilometers per second at perihelion. But Voyager 1 will be our first craft to reach interstellar space, and it continues to be a measure of how frustratingly far even the nearest stars happen to be.

Cautionary notes are needed when a sudden burst of enthusiasm comes to these subjects, as it seems to have done with the discovery of Centauri B b. What we need to avoid, if we’ve got our eyes on long-term prospects and a sustained effort that may take centuries to succeed, is minimizing the challenges of an interstellar journey. Making it sound like a simple extension of existing interplanetary missions would create a public backlash once the real issues become clear. Better to be straightforward, to note the vast energy budget needed by an interstellar mission, the conundrum of propulsion, the breathtaking scope of the distances involved.

Image: The night sky above Mt. John Observatory in New Zealand, where a second active hunt for Alpha Centauri planets has taken place. This and a third Centauri project, Debra Fischer’s work at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (Chile), give us hope that Centauri B b may be confirmed in the near future. Note the Southern Cross (just above and to the right of the dome), with Alpha and Beta Centauri the two stars to its left. Alpha Centauri (the leftmost bright star) is a triple system made up of Centauri A, Centauri B and Proxima Centauri. Credit: Fraser Gunn.

Marc Millis told Alan Boyle just after the Centauri B b discovery that manned missions were almost certainly not going to be our first attempts to reach the stars. We can work out scenarios where the global economy grows to the point where a civilization moving into the Solar System can afford to build huge laser installations that could propel a lightsail to perhaps ten percent of the speed of light. Get up to that kind of velocity and you make the Centauri crossing in less than half a century, but only for a flyby. Deceleration is another matter, and even if, as Robert Forward showed, there may be ways to decelerate a lightsail at destination, the mission then extends to at least a century and, given our assumptions, perhaps a good deal more.

So we’re likely talking about robotic probes which, given the development time needed to create and launch them, would probably be ‘manned’ by an extremely sophisticated artificial intelligence. In the same article, astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch (Washington State) told Boyle that an interstellar mission could be seen as part of a roadmap that developed incrementally:

“The roadmap that we have takes a grand perspective, with the objective to scout out our own solar system first, put a permanent human presence on Mars, look at asteroids, and really work first on our own solar system before we take the next step to an extrasolar planet.”

And as I’ve speculated here on more than one occasion, a developmental model like this may take a more gentle trajectory than we’ve previously assumed. A civilization that masters living in nearby space by developing large habitats that can house thousands may eventually branch off from its Earthbound human roots to thrive in the places between planets and stars. Generations may indeed live and die in such habitats not because of a specific mission constraint but as a matter of choice. And if this occurs, a mission to a nearby star may be an organic extension of space living, its destination motivated by long-term curiosity rather than any plans of settlement.

Centauri B b is hardly a compelling target for any kind of mission, but the enthusiasm it has already generated points to the latent exploratory impulse that may be triggered if we do find a habitable world somewhere among the Centauri stars. In another recent piece on the discovery, Ian O’Neill quotes Robert Freeland, deputy project leader for Project Icarus, the ongoing re-design of the 1970s Project Daedalus starship study. Like me, Freeland is pondering how the public would react to the next round of Centauri discoveries, assuming such are made:

“I have often imagined the day when scientists directly image an Earth-like extra-solar planet. We would be able to determine the planet’s atmosphere and surface temperature from its spectrum, and we would thus know whether it might be able to sustain life as we know it. I suspect that once such a discovery hits the news, people worldwide are going to demand that we send a probe to determine whether the planet has life (of any type) and/or could be suitable for human habitation. If the latter proves true, then a manned mission would eventually follow.”

A lot can happen, of course, between the surging interest such a discovery would create and the realization of how tough a mission like this would be. But Freeland is surely right that Centauri B b is a warning shot that tells us we’ll be finding much more about this system in the not so distant future. While it is true that the HARPS spectrograph that made the recent discovery possible is capable of detecting planets no smaller than four Earth masses in the habitable zone of Centauri B, Stéphane Udry (Observatoire de Genève) said in the recent news conference that ESO was already working on technologies that would extend that range down to one Earth mass.

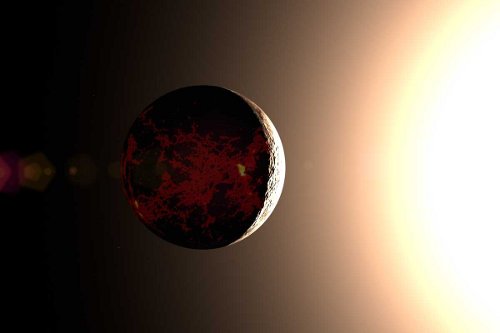

Image: An artist’s impression of Centauri B b. Credit: Adrian Mann.

Meanwhile, supported by the Planetary Society, Debra Fischer (Yale University) has been working on a separate search for Alpha Centauri planets, one she recently discussed with Bruce Betts. Fischer notes how faint the 0.5 m/s signal seen by the Geneva team is and points to the need to confirm the discovery. Her team, which has been talking with the HARPS researchers, has been analyzing its own dataset and running simulations to test detectability. Says Fischer:

“Our best data set for aCenB begins in June 2012, when we completed some stability upgrades to the new spectrograph (CHIRON) that we built for the 1.5-m CTIO telescope (with NSF MRI funding). Our precision since the upgrade matches the HARPS precision, but yields a 5-month string of data compared to the 5-year time baseline of data from HARPS.”

And she adds:

“We are in an excellent position to follow-up, but that will likely require an intensive search over the prospective orbital period of 3.24d when the star rises again in January 2013.”

Would the discovery of a habitable zone planet around Centauri B, perhaps occurring some time in the next ten years, have the effect Freeland believes it would? Given the state of our technology, we couldn’t get off an interstellar mission any time soon, but I would like to think that such a finding would be a spur to research that might turn interstellar studies from a back-burner activity into a more visible and better funded effort. We need to advance the technologies that will help us with in-system projects, from long-term life support to advanced robotics. And we can hope that eventually, a Solar System-wide civilization may emerge that will have the strategies and the energy budget to consider a close-up look at such a distant, tantalizing target.

Reflections on Centauri B b

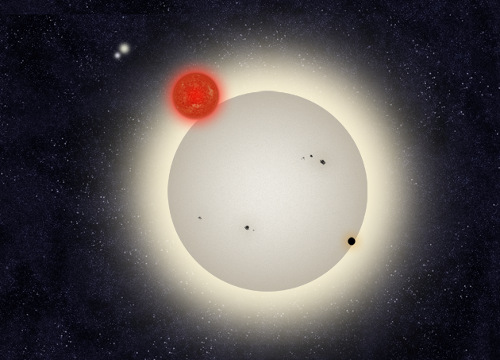

When planet-hunter Greg Laughlin (UC-Santa Cruz) took his turn at the recent press conference announcing the Alpha Centauri B findings, he used the occasion to make a unique visual comparison. One image showed the planet Saturn over the limb of the Moon, as shown immediately below in a 1997 photo from Krzysztof Z. Stanek. Think of this as the Galilean baseline, for when Galileo went to work on the heavens with his first telescope, the Moon was visually close at hand and Saturn a mysterious, blurry object with apparent side-lobes.

Laughlin contrasted that with the image I ran yesterday, showing the Alpha Centauri stars as viewed from Saturn, a spectacular vista including the planet and the tantalizing stellar neighbors beyond. Four hundred years after Galileo, we thus define what we can do — a probe of Saturn — and we have the image of a much more distant destination we’d like to know a lot more about. The findings of the Geneva team take us a giant step in that direction, revealing a small world of roughly Earth mass in a tight three-day orbit around a star a little smaller and a little more orange than the Sun. What comes next is truly interesting, both for what is implied and for what we are capable of doing.

Image: Have another look: Alpha Centauri as seen from Saturn space. These days we can see Saturn’s features in sharp detail thanks to Cassini, but Centauri A and B remain distant and enigmatic. The discovery of Centauri B b is the first step in sharpening our focus. Credit: JPL/NASA.

Be sure to check Alpha Centauri B b on Greg’s systemic blog for his latest thoughts.

Closing on Alpha Centauri

Surprisingly, there is a 10 percent chance that Centauri B b is a transiting world, and a slightly higher chance still if the new planet is in the orbital plane of the binary stars. Remember, the primary Centauri stars are just eleven degrees from being seen edge-on to us. We’re talking about a very challenging detection scenario, but one that’s not out of the question for an instrument like the Hubble Space Telescope. Clearly, a transit would be a major boost, allowing us to determine the radius and the density of the planet (and, obviously, confirming its existence). Stéphane Udry (Observatoire de Genève) told the news conference that a proposal to examine Centauri B for transits has already been sent to the Hubble team.

Radial velocity work on the Centauri stars has proven tricky business, requiring 500 nights of observing time spread over a nine year period. But things are going to get a bit more complicated still, as Laughlin explained in an email on Tuesday. For Centauri A and B are not exactly static, and stray light from the brighter Centauri A can contaminate the studies of B:

I really like the particular way that the narrative is unfolding. The presence of the 3.2-day planet, taken in conjunction with the myriad Kepler candidates and the other results from the HARPS survey, quite clearly points to the possibility, and I would even say the likelihood, of finding additional planets at substantially more clement distances from the star. Alpha Cen A and B, however, are drawing closer together over the next several years, severely metering the rate at which high-precision measurements can be obtained. This builds suspense! It reminds me a bit of a mission like New Horizons, where the long coast to the destination serves to build a groundswell of excitement and momentum for the dramatic close encounter.

At the news conference, Laughlin likened our current state to halftime at a football game. We’ve pulled out a major detection but even as we start to speculate about rocky worlds further out in the system, we’re faced with increasingly difficult observations. We can expect the Alpha Centauri story to unfold slowly, but Xavier Dumusque (Centro de Astrofísica da Universidade do Porto) pointed out how much more difficult it becomes to find planets as we move further out in the Centauri B system, adding that it would take at least twice as many measurements as the Geneva team has now made. Right now the researchers are saying the HARPS spectrograph might be limited to a planet with a lower mass limit of about four Earth masses here, but Stéphane Udry added that new ESO instrumentation was in the works that offered, in the not so distant future, good prospects for finding an Earth-mass planet in the habitable zone.

A 230-day orbit around Centauri B should put us right in the middle of the habitable zone, the place we’d most like to find a terrestrial world. Fortunately, it’s a region of orbital stability — the effects of Centauri A only become problematic as we move as much as 3 AU out from the star. Before we can find a habitable zone planet, we’ll need to confirm Centauri B b and begin to study it, which is where that useful transit could come in. The probable picture is stark — a rocky, lava-world with a surface temperature somewhere around 1500 Kelvin, surely in a tidally locked orbit. Not exactly a clement place, but the implication of other worlds in this system will urge us forward.

Putting the new planet in perspective involves seeing the overall picture of exoplanet research, which could be changed by the discovery. In his email, Laughlin noted the possibilities:

I think that this is important for a society that is increasingly expectant of immediate interactivity and instant gratification… I hope that this detection of Alpha Cen B b provides an impetus for the funding of additional radial velocity infrastructure, and also for space-based missions such as TESS, which can find and study the very best planets orbiting the very nearest stars.

Will the focus now shift from the statistical wonders being revealed by Kepler to the many nearby stars about which we have little planetary information? We saw the other day that the ESA mission concept called NEAT offers new ways to study Alpha Centauri and other nearby stars, and TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) is likewise out there as a concept that would allow us to survey 2.5 million of the brightest stars in the sky. Data from a mission like this could be handed off to the James Webb Space Telescope for more intense investigation. All that depends on funding and the continued awakening of interest in planets around neighboring stars.

The Choice of Centauri B

We have three stars in the Alpha Centauri system, but Centauri B has been at the center of the current effort, not only by the Geneva team but by Debra Fischer’s team and a third group in New Zealand. Why Centauri B and not its brighter partner, Centauri A? Both could have planets, and in the case of A we can’t rule out planets as large as ten Earth masses (gas giants would probably have been detected by now). What a fascinating scenario that is: Two planetary systems, each with the possibility of a planet in the habitable zone. Imagine the spur to space travel that would give any civilization there, to find a habitable world within easy striking distance!

The focus is on Centauri B because it is a more promising study for the radial velocity methods used in this investigation. Its level of stellar activity is low, which means there are fewer perturbations that can distort radial velocity measurements. It’s also a cooler star than our Sun, which means the habitable zone will be closer to the star than around the brighter Centauri A. Remember that with radial velocity methods we’re looking at incredibly tiny distortions in the movement of the star (in the case of Centauri B b, 51 centimeters per second, or 1.8 kilometers per hour, the highest precision ever achieved using this method). A smaller mass means stronger radial-velocity variation for a planet of similar mass, hence an easier detection.

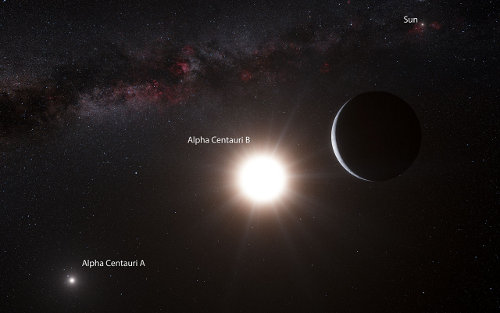

Image: An artist’s impression of the planet orbiting Alpha Centauri B, a member of the triple star system that is the closest to Earth. Alpha Centauri B is the most brilliant object in the sky and the other dazzling object is Alpha Centauri A. Our own Sun is visible to the upper right. The tiny signal of the planet was found with the HARPS spectrograph on the 3.6-metre telescope at ESO’s La Silla Observatory in Chile. Credit: ESO/L. Calçada/N. Risinger (skysurvey.org).

Not that Centauri B is an easy target. There are plenty of factors intrinsic to the star that can introduce jitter in these observations and thus render planet detection difficult. A huge part of the Geneva team’s work has been to examine HARPS spectrograph observations between February 2008 and July 2011 to model and remove all non-planetary sources of perturbation. From the paper:

The raw radial velocities of α Centauri B… exhibit several contributing signals that we could identify. Their origin is associated with instrumental noise, stellar oscillation modes, granulation at the surface of the star, rotational activity, long-term activity induced by a magnetic cycle, the orbital motion of the binary composed of a Centauri A and B, light contamination from a Centauri A, and imprecise stellar coordinates.

Each of these factors had to be modeled and subtracted from the data. The team performed Monte Carlo simulations to check against the signal at 3.236 days being an artifact from the elimination of the stellar signals and was able to conclude that the signal is real. Xavier Dumusque, lead author of the discovery paper, showed the press conference graphs of Centauri B’s magnetic activity, noting that as the latter went up, radial velocity jitter increased. Notice how subtle these effects are and remember that they must be understood to get the real picture:

For the Sun, as for other stars similar to α Centauri B in spectral type, convection induces a blueshift of the stellar spectra. Therefore, no convection means no convective blueshift inside these regions, and so the spectrum of the integrated stellar surface will appear redshifted. Because a redshift means a measured positive radial velocity, a positive correlation between the magnetic cycle variation and the long-term radial velocity variation is then expected.

Get the noise out of the data and that 51 centimeter per second signal persists as Centauri B b.

Significance of the Find

There was a sense of exhilaration in the air on Tuesday as the buzz around an Alpha Centauri planet built, and when the embargo was lifted, reports of the find filled the social media as the early articles began to appear online. Just how big a deal is Centauri B b? A skeptic could point out that while finding an Earth-mass planet is significant, it must still be confirmed, and in any case, this is an Earth-mass planet that is nothing like a clement, habitable world. Then too, the level of investigation involved here was so intense that it may be years before we learn about other planets in this system, not to mention planets around Centauri A or Proxima.

NASA’s John Grunsfeld, Science Mission Directorate Associate Administrator for the agency, had this to say about NASA’s plans in the days after the discovery:

“NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will provide a unique facility that will serve through the next decade as the mainstay for characterization of transiting exoplanets. The main transit studies JWST will be able to undertake are: discovery of unseen planets, determining exoplanet properties like mass, radius, and physical structure, and characterizing exoplanet atmospheres to determine things like their temperature and weather. If there are other planets in the Alpha Centauri system farther from the star, JWST may be able to detect them as well through imaging.

“NASA is also studying two medium-class exoplanet missions in our Explorer program, and in the spring of 2013 will select one of them to enter development for flight later in the decade.”

Clearly the game is afoot. A confirmed Centauri B b would tell us that planet formation is indeed possible in the nearest stellar system to our own — this had by no means been obvious, and the debate over planet formation mechanisms in close binaries has been brisk. The presence of a rocky planet here obviously implies the presence of other worlds, and the Geneva team holds out strong hope that we’re up to the task of finding them. From the paper:

The optimized observational strategy used to monitor α Centauri B is capable of reaching the precision needed to search for habitable super-Earths around solar-type stars using the radial-velocity technique. However, it requires an important investment in observation time, and thus only few targets can be observed over several years. Recent statistical analyses and theoretical models of planetary formation suggest that low-mass rocky planets and especially Earth twins should be common. We are therefore confident that we are on the right path to the discovery of Earth analogues.

Alpha Centauri is obviously a prime target for any future interstellar probe because it is so much closer than other stars. Space-based instrumentation will one day be able to tell us something about the larger Centauri B system, assuming other planets are present. The discovery of a terrestrial world in the habitable zone here would be a spur to exploration that could drive public interest and funding for increasingly sophisticated technologies. Maybe a distant but theoretically reachable green and blue world is out there around our nearest neighbor, but we won’t know until we commit the resources to continue the investigation. Centauri B b is an exciting start to characterizing this fascinating system, a process that will demand time, patience, and effort just as rigorous as the Geneva team put in here. Well done to all involved!

Alpha Centauri and the New Astronomy

For much longer than the nine years Centauri Dreams has been in existence, I’ve been waiting for the announcement of a planetary discovery around Centauri B. And I’m delighted to turn the first announcement on this site over to Lee Billings, one of the most gifted science writers of our time (and author of a highly regarded piece on the Centauri stars called The Long Shot). Lee puts the find into the broader context of exoplanet research as we turn our gaze to the nearest stars, those that would be the first targets of any future interstellar probes. On Thursday I’ll follow up with specifics, digging into the discovery paper with more on the planet itself and the reasons why Centauri B was a better target than nearby Centauri A. I’ll also be offering my own take on the significance of the find, which I think is considerable.

by Lee Billings

For much of the past century, astronomy has been consumed by a quest to gaze ever deeper out in space and time, in pursuit of the universe’s fundamental origins and ultimate fate. This Old Astronomy has given us a cosmological creation story, one which tells us we live in but one of innumerable galaxies, each populated with hundreds of billions of stars, all in an expanding, accelerating universe that began 13.7 billion years ago and that may endure eternally. It’s an epic, compelling tale, yet something has been missing: us. Lost somewhere in between the universe’s dawn and destiny, passed over and compressed beyond recognition, is the remarkable fact that 4.5 billion years ago our Sun and its worlds were birthed from stardust, and starlight began incubating the planetary ball of rock and iron we call Earth.

Somehow, life emerged and evolved here, eventually producing human beings, creatures with the intellectual capacity to wonder where they came from and the technological capability to determine where they will go. Uniquely among the worlds in our solar system, the Earth has given birth to life that may before the Sun goes dim reach out to touch the stars. Perhaps, on other worlds circling other suns, other curious minds gaze at their night skies and wonder as we do whether they are alone. In this coming century, a New Astronomy is rising, one that focuses not on the edge of space and the beginning of time but on the nearest stars and the uncharted worlds they likely hold. It will be this New Astronomy, rather than the Old, that will at last complete the quest to place our existence on Earth within a cosmic context.

In a major leap forward in this enterprise, today a European planet-hunting team announced their discovery of an alien world about the same mass as Earth. This alone would be noteworthy, for of all the “exoplanets” now known beyond our solar system, only a very few, and very recently, have been shown to at all resemble our own. But there is more to the story. This particular exoplanet resides in a three-day orbit around the dusky orange star Alpha Centauri B, a member of the Sun’s closest neighboring stellar system. There are two other stars in the system as well, the yellow Sun-like star Alpha Centauri A and the red dwarf star Proxima Centauri.

Astronomers began discovering exoplanets about two decades ago, finding at first a few per year. Since then, the pace of discovery has dramatically accelerated. Today there are more than 750 confirmed exoplanets, and a single NASA mission, the Kepler spacecraft, has detected more than 2,300 additional candidates that await confirmation. Most of these exoplanets are far too large, too hot, or too cold to support life as we know it, but a handful appear to be “Goldilocks” worlds the right size and the right distance from their stars where liquid water could flow in streams and pool in seas, worlds where carbon-based organisms could potentially thrive. The discovery of more Goldilocks worlds appears inevitable — statistics from the Kepler mission and other sources suggest that somewhere between ten to thirty percent of stars harbor potentially habitable planets. Among the planet-hunters, the question is no longer whether life exists elsewhere in the universe, but rather how far removed the next-nearest living world might be.

At a distance of just over 4.3 light years, the stars of Alpha Centauri are only a cosmic stone’s throw away. To reach Alpha Centauri B b, as this new world is called, would require a journey of some 25 trillion miles. For comparison, the next-nearest known exoplanet is a gas giant orbiting the orange star Epsilon Eridani, more than twice as far away. But don’t pack your bags quite yet. With a probable surface temperature well above a thousand degrees Fahrenheit, Alpha Centauri B b is no Goldilocks world. Still, its presence is promising: Planets tend to come in packs, and some theorists had believed no planets at all could form in multi-star systems like Alpha Centauri, which are more common than singleton suns throughout our galaxy. It seems increasingly likely that small planets exist around most if not all stars, near and far alike, and that Alpha Centauri B may possess additional worlds further out in clement, habitable orbits, tantalizingly within reach.

Anyone in the Southern Hemisphere can look up on a clear night and easily see Alpha Centauri — to the naked eye, the three suns merge into one of the brightest stars in Earth’s sky, a single golden point piercing the foot of the constellation Centaurus, a few degrees away from the Southern Cross. In galactic terms, the new planet we’ve found there is so very near our own that its night sky shares most of Earth’s constellations. From the planet’s broiling surface, one could see familiar sights such as the Big Dipper and Orion the Hunter, looking just as they do to our eyes here. One of the few major differences would be in the constellation Cassiopeia, which from Earth appears as a 5-starred “W” in the northern sky. Looking out from Alpha Centauri B b and any other planets in that system, Cassiopeia would gain a sixth star, six times brighter than the other five, becoming not a W but a sinuous snake or a winding river. Cassiopeia’s sixth bright point of light would be our Sun and its entire planetary system.

Image: Alpha Centauri as seen by the Cassini orbiter above the limb of Saturn. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

Despite its close proximity, as with nearly all other known exoplanets, Alpha Centauri B b is as yet unseen. It was detected indirectly, via a periodic 50-centimeter-per-second wobble its orbit raises in the motions of its star, in a painstaking process that took four years of nightly monitoring and careful analysis. The wildly successful Kepler mission finds the bulk of its candidates by a different technique, looking for the minuscule diminution of a star’s light when, by chance, a planet in its orbit transits across the star’s face and casts a shadow toward Earth. Both of these discovery methods can constrain the most basic properties of a planet: its orbit, its mass, and perhaps its size and bulk composition. But neither can readily reveal whether or not any potentially habitable planet is actually a place much like Earth. To do that really requires taking a planet’s picture. Even if that picture amounted to only a meager clump of pixels, astronomers might discern within it a planet’s rotational period — the length of its days — as well as clouds, oceans, and continents. The reflected planetary light would also contain spectroscopic signatures of atmospheric gases. Carbon dioxide would suggest a rocky planet, and water vapor would hint at oceans or seas. Detecting oxygen and methane — gases produced on Earth by living things — would further suggest that the distant planet was not only habitable, but inhabited.

Viewed over interstellar distances in visible light, the Earth is some ten billion times fainter than the Sun, meaning that for every photon bouncing off Earth’s atmosphere or surface, ten billion more are flying out from our star. About the same ratio would apply for any habitable planet around Alpha Centauri’s stars. Distinguishing such faint planetary light from that powerful stellar glare is rather like spotting a firefly hovering a centimeter away from the world’s most powerful spotlight, when the spotlight is in Los Angeles and you are in New York. To see the firefly, that overwhelming ten-billion-to-one background light must be suppressed.

Amazingly, on paper and in laboratory studies, astronomers have already devised multiple ways to do exactly this for potentially Earth-like planets that may exist around nearby stars. Most of these methods require an entirely new multi-billion-dollar space telescope, though a few proposals exist to augment NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope with starlight-suppressing technology at an estimated cost of $700 million. Considering that three years ago a film about life on Alpha Centauri’s planets — James Cameron’s Avatar — grossed some $2 billion in box-office receipts, it stands to reason there is public appetite to spend at least that much on space telescopes to search for the real thing.

Matt Mountain, the director of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, likes to quip that the discovery of life beyond our solar system could be to this coming century what Neil Armstrong’s lunar footprints were to the last. Yet today NASA is not seriously funding any life-finding telescopes, and has no real plans to do so in the future. The agency instead is spread thin and lacking any unified direction, strapped for cash and struggling to avoid obsolescence while it maintains the International Space Station, builds a new fleet of rockets to replace the retired Space Shuttles, and completes the James Webb Space Telescope. Yet obsolescence is precisely what NASA will embrace if it fails to invest now in the next giant leap required for this New Astronomy. Of all the scientific institutions and agencies upon this planet, at present NASA alone has the resources to build a telescope capable of directly imaging and characterizing any Earth-like planets around nearby stars. Unless it does so, as the list of potentially habitable planets grows long in years to come, all that shall grow along with it will be our ignorance of what those distant worlds are actually like and what may live upon them.

Meanwhile powerful, influential Old Astronomy, which has revolutionized our understanding of the universe at its largest scales, is wary of the New, and at times has acted quite deliberately against it. Alas, government-funded Big Science is too often a zero-sum game, one in which money that could go toward looking for life on exoplanets around nearby stars would be taken from cosmological efforts to study far-distant galactic clusters and the expansion of the universe. In a perfect world we would fully fund both quests simultaneously. But our world — with its economic instabilities, rising temperatures, growing populations, and plummeting biodiversity — seems to grow more imperfect by the day, in ways that no knowledge of dark energy or dark matter is likely to ever assuage. The New Astronomy is different. We do not yet know whether planets like ours and creatures like us are in fact common or rare in the cosmos, but by trying to find out, we will unavoidably learn just how precious our planet truly is. Perhaps, with luck, discoveries following from today’s announcement will help us finally kick off from our small blue footstool, and find our way among the stars.

Lee Billings is working on a book about the search for other Earth-like planets, forthcoming from Penguin/Current next fall.

Circumbinary Planet in a Four Star System

Continuing with what promises to be a seriously interesting week in exoplanet studies, I want to home in this morning on PH1, a planet that reminds us how much the public has become involved in ongoing science thanks to the widespread distribution of computer power. As presented at the annual meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society in Reno (NV), the finding pairs volunteers working with the crowdsourced Planet Hunters project with an international team of professional astronomers led by Yale University’s Meg Schwamb.

The volunteers — Kian Jek of San Francisco, California, and Robert Gagliano of Cottonwood, Arizona — were the first to spot the telltale lightcurve of a transit, which was then confirmed by astronomers using the Keck instruments at Mauna Kea (Hawaii). What the investigation uncovered was a gas giant about 6.2 times the radius of the Earth, putting it into Neptune-territory. But what really flags the attention is the fact that PH1 orbits within a four-star system. The planet is on a circumbinary orbit of two stars — with mass of 1.5 and 0.41 times the Sun respectively — every 138 days. At about 1000 AU in the same system is a second binary pair orbiting the first.

The inner pair comprise an eclipsing binary tagged KIC 4862625, located in the Kepler field and examined by the Planet Hunters duo using the first six quarters of publicly available Kepler data. PH1 is the seventh confirmed transiting circumbinary planet, giving us new information about the orbital configurations of multi-star planetary systems. From the paper:

These planetary systems provide new boundary conditions for planet formation This ever increasing sample of dynamically extreme planetary systems will serve as unique and vital tests of proposed planetesimal formation models and core accretion theories…

Image: A family portrait of the PH1 planetary system: The newly discovered planet is depicted in this artist’s rendition transiting the larger of the two eclipsing stars it orbits. Off in the distance, well beyond the planet orbit, resides a second pair of stars bound to the planetary system. Credit: Haven Giguere/Yale.

As for Planet Hunters, the Yale researchers believe the ‘citizen science’ model may continue to play a role in gaining new information about such systems:

PH1 was found serendipitously by Planet Hunters volunteers examining the light curves of the known Kepler eclipsing binaries. The discovery of PH1 highlights the potential of visual inspection through crowd sourcing to identify planet transits in eclipsing multistar systems, where the primary and secondary eclipses of host stars make detection challenging compared to planets with single host stars. In particular, Planet Hunters may exploit a niche identifying circumbinary planetary systems where the planet is not sufficiently massive to produce measurable eclipse timing variations that would be identifiable via automatic detection algorithms.

Co-author Jerome Orosz (San Diego State) echoes the sentiment, saying that “Many of the automated techniques used to find interesting features in the Kepler data don’t always work as efficiently as we would like.” Putting many sets of eyes on the data becomes a potent tool when linked up with the professional instrumentation and judgement needed to confirm the find. For more, see this Yale University news release. The paper is Schwamb et al., “Planet Hunters: A Transiting Circumbinary Planet in a Quadruple Star System,” submitted to The Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

Exoplanet Missions Beyond Kepler

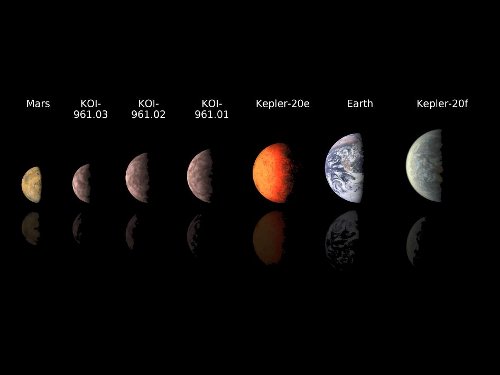

Because it’s going to be an interesting week for exoplanet studies (for reasons I’ll talk about soon, though not today), I’ll lead off with some thoughts on eta-Earth, defined as the fraction of Sun-like stars with a planet like Earth orbiting them. We have a lot to learn about the frequency of terrestrial worlds, and as Philip Horzempa points out in a recent article for The Space Review, the image that’s gradually emerging is of fewer ‘Earths’ than Carl Sagan once estimated when he said in the 1980s that half of all stars could have a planet like our own.

Image: Artists’ concepts of small exoplanets compared to our own planets Mars and Earth. As Kepler continues to hunt, how can we move beyond its findings to learn more about terrestrial planets around much closer stars? Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

With Kepler’s continuing datastream and improving ground-based instrumentation, we’re learning more about planet distribution, but Horzempa notes that even now, estimates of Earth analogs have ranged from about 2 percent to as high as 35 percent. He cites John Rehling, who went to work on biases inherent in the Kepler data set, namely that 1) the Kepler data are more complete in regions close to the host star and 2) the transit method detects larger planets more readily than small ones (see Looking Into Kepler’s Latest for more on this analysis, which appeared last March). Rehling’s findings led him to support a low 2% figure for eta-Earth but more complete Kepler data now has him backing off the number. Here’s what Horzempa says on the matter:

[Rehling’s] analysis has shown that the abundance curves for certain planet types, such as super-Earths, do not follow a smooth distribution curve. Rather, there is a peak, followed by a falloff, with increasing distance from the parent star. The distribution curve for Earth-sized worlds shows a positive slope, so far. Therefore, at present the best that can be said about eta-Earth is that it probably has a value of 2-12%. Only an extended Kepler mission will be able to determine the actual fraction of stars that have an Earth orbiting it. A low value for eta-Earth will mean that the search for Earth analogs in nearby solar systems will need to be pursued with vigor, and with multiple approaches.

Kepler, of course, is working with a large field of stars about 2000 light years away, the idea being to gather statistical information that will help us understand the broad trends of planet distribution. The mission has been extraordinarily successful, but it’s interesting to speculate, as Horzempa does, on what missions could now follow up on its findings. The article looks at the Gaia space telescope that should be operational by 2014 as well as the New Worlds sunshade concept that could be deployed for use with the James Webb Space Telescope, but I want to focus on Horzempa’s third mission concept, an ‘Earth’ finder called NEAT.

The Nearby Earth Astrometric Telescope has been proposed to the European Space Agency as a mission that could home in on nearby terrestrial planets in ways Kepler cannot. The idea here is to fly a pair of spacecraft separated by some 40 meters, providing the needed focal length to create high angular resolution. One of the spacecraft carries a 1-meter mirror while the other is a detector probe that collects the focused light onto an array of CCDs. The goal is to detect Earth analogs within 50 light years, with an accuracy of 0.05 microarcseconds for selected targets. Says Horzempa:

The NEAT duo will observe a list of 200 nearby Sun-like stars over several years. It will be able ascertain whether planets down to a mass of 1 Earth, or larger, orbit those stars. In addition, NEAT will be able to survey the solar systems discovered by Kepler, detecting giant planets that were missed by Kepler. These would be planets that did not transit their parent star during the Kepler mission, either because of the “wrong” orbital inclination or because their orbital period is too long. This will help to “fill in” the architecture of those solar systems, allowing a better understanding of how those systems are formed.

As you can see, NEAT would require formation flying in space, something that will demand a precursor experiment that the French space agency CNES has already funded, drawing on progress in formation flying that has been achieved by Sweden’s PRISMA program. The hope of the NEAT planners is to move beyond this experiment to a smallsat follow-up called micro-NEAT, which would put the formation flying algorithms through their paces, though at a separation of 12 rather than 40 meters. Quite a lot of serious work could emerge from such a mission: Horzempa notes that micro-NEAT would be able to detect planets down to one Earth mass for our nearest neighbors, Alpha Centauri A and B. It would also be able to detect larger planets (with a lower mass limit of 10 Earth masses) around the 25 nearest stars.

You’ll want to read all of Horzempa’s essay, which will include a second installment to be published today. With funding for projects like DARWIN and Terrestrial Planet Finder in perpetual limbo, smaller missions that can advance the exoplanet hunt — and help us refine the value of eta-Earth — are the next priority. They will be designed and, let’s hope, fly in an environment enlivened with still more detailed findings from our existing space observatories as well as instruments on the ground that reveal planets in the habitable zone of their stars.

NEAT was submitted as an answer to the call for proposals for M-class space missions in ESA’s “Cosmic Vision 2015-2025” plan. For more, see Mablet et al., “High precision astrometry mission for the detection and characterization of nearby habitable planetary systems with the Nearby Earth Astrometric Telescope (NEAT),” available online. The NEAT proposal summary is also available. A NEAT workshop was held in November of 2011 in Grenoble, France.