Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Wrapping Up the Houston Starship

Because I utterly lack their skills, I have huge admiration for practical-minded people who can organize things well. Eric Davis’ work as track chair for the ‘Time and Distance Solutions’ track in Houston is a case in point. The challenge is in coping with a key fact of interstellar studies: We are so early in the game that we have not remotely figured out which propulsion method makes the most sense for journeys of this magnitude. Discussing time and distance means culling papers to find a balance of ideas, from what could be near-term (fusion, although it always seems near-term) to highly speculative (antimatter and nanotech).

Image: Physicist Eric Davis, a highly visible figure at the Houston conference.

Eric nailed the composition of the track, and it was because of that that I stayed in it through the conference. The temptation of getting involved with alternate tracks on ‘Becoming an Interstellar Civilization’ and especially ‘Destinations and Habitats’ was huge, but it was the time and distance problem that first drew me to interstellar studies so that is where I stayed. I’m hoping that Eric as well as several other track chairs will be able to offer their thoughts in future Centauri Dreams articles on how their sessions went.

Sleepless in Houston

Mae Jemison, who runs the 100 Year Starship organization, was everywhere, and I was beginning to wonder if she ever slept. She was in meetings all day Wednesday with the advisory council and later the track chairs, then in constant motion afterwards, a highly visible figure who never seemed to run out of energy. Gordon Gould and I asked her at lunch on Thursday about her flight aboard Endeavour in 1992, curious about what it is like to actually be blasted into space. We’ve all seen Shuttle launches and know how impressive, noisy and fearsome they can be.

But Mae said the effect was actually quite different. “You’re so wrapped up in padding and shielded from the noise that from inside, it’s just like being in the simulator. Remember that you have to hear all the communications inside the craft, so the noise seems very far away.” I had the same reaction a few months back when I asked Shuttle astronaut Drew Feistel, a veteran of Hubble Space Telescope repairs, whether that sweeping roll the Shuttle used to perform on liftoff was as dramatic from inside as it appeared to spectators. And the answer was no. Drew said you mostly felt acceleration, and that the roll maneuver felt very gradual and unobtrusive.

The job ahead of Mae’s group is, of course, enormous, and a huge part of that job will be to connect to a public that is both hamstrung by economic concerns and largely out of the kind of space mode we saw back in the Apollo days. My thought on that is that an organization like the 100 Year Starship can do a world of good by helping to get the word out about what interstellar issues really are. It’s surprising how few people realize the distances we’re talking about — when I first arrived in Houston, I cited in these pages the person who had emailed me with the question: “We’re already going to Pluto. How much harder can it be to go to a star?”

I gave a flip answer to that question in my earlier post, but it’s indicative of the mind-boggling nature of the time and distance conundrum and how little it is perceived by the public. I think we need to communicate how enormously challenging it will be to go to the stars at the same time that we provide a sound rationale for methodically looking at the problem. It is not using scare tactics to suggest that Earth’s history has been violent and that asteroid or comet impacts are not necessarily all in the past. And it is not being overly sanguine to say that the kind of solutions that will enable a crewed starship — maintaining sound ecologies, for example — are solutions that will have resonance on our own green planet and will help us to preserve it.

Spinoffs are always a touchy subject in spaceflight terms because they’re so easily ridiculed, and the average citizen is more likely to think of Tang than of GPS as a result of space research. But this is simply a hurdle that must be cleared for an organization with a 100-year mission to succeed. Learning how to propel a payload at a small percentage of lightspeed could have enormous ramifications for our production and use of energy on Earth, while the demand for autonomous systems will propel us into major advances in artificial intelligence and robotics. As one speaker noted, whether manned or not, a starship will demand autonomous systems.

Image: Mae Jemison addresses the crowd at Saturday night’s gala.

Into the Cosmic Sea

Let me close my Houston coverage with some thoughts about Jill Tarter. The SETI legend spoke to the symposium at large on Saturday in a short, inspiring talk outlining the search for Earth 2.0. We have yet to detect proof of an extraterrestrial civilization after 50 years of searching, but Tarter is doubling down on the need to keep looking given the small sample in our searches:

“Think about an Earth ocean as an analog. We’ve sampled the equivalent of one eight ounce glass out of that ocean in 50 years. Now you might get lucky and scoop up a fish when you do something like that, but chances are you wouldn’t. So our sample is small, inadequate. A cosmic ocean is out there beckoning us — the monumental task of sampling it remains… Our search must be audacious and inclusive. SETI trivializes the differences among us, and if it does nothing but expose every human being on the planet to this perspective, it will still have been one of the most significant events in human history.”

What might we pick up? Tarter said we will discover that Earth 2.0 in short order, meaning an Earth-mass planet in the habitable zone of a Sun-like star, but added that for it to truly be Earth 2.0, it will need to be inhabited. A technology we might detect could be anything from a beacon to a vast communications network, or perhaps huge shields against asteroid impacts or a completely unforeseen technology that could be generating radio or optical signals. “If we find technology, we can infer intelligence,” she added. “We can’t directly detect intelligence.”

Tarter’s message resonated with a crowd that, like her, believes we are a very young technology in a very old galaxy. A key question: Is it possible for a technological civilization to last for cosmic lengths of time? If the answer is no, Tarter believes SETI will fail, but of course we all hope the answer is yes. It was Philip Morrison, co-author of the first major paper on SETI, who called the idea “the archaeology of the future.” Sifting through the faint signals that impinge upon our dishes from the galaxy around us, we hope, unlike archaeologists, to find not just enigmatic remains but a living presence whose very existence will add meaning to our place in the cosmos.

In going forward, both in SETI and in the 100 Year Starship initiative, I’m reminded of Mae Jemison’s quote from Bash?, the greatest poet of the Edo period in Japan. Bash?’s wanderings into unknown country made him a legend, giving him material for his work and renewed purpose. He had learned from experience the lesson he conveyed here: “Seek not to follow in the footsteps of men of old; seek what they sought.”

A Lab Experiment to Test Spacetime Distortion

Sonny White’s work on exotic propulsion has galvanized the press, as witness this story in the Daily Mail, one of many articles in newspapers and online venues. I was fortunate enough to be in the sessions at the 100 Year Starship Symposium where White, an engaging and affable speaker, described what his team at Eagleworks Laboratories (Johnson Space Center) is doing. The issue at hand is whether a so-called ‘warp drive’ that distorts spacetime itself is possible given the vast amounts of energy it demands. White’s team believes the energy problem may not be as severe as originally thought.

Here I’ll quote Richard Obousy, head of Icarus Interstellar, who told Clara Moskowitz in Space.com: “Everything within space is restricted by the speed of light. But the really cool thing is space-time, the fabric of space, is not limited by the speed of light.”

On that idea hangs the warp drive. Physicists Michael Pfenning and Larry Ford went to work on Miguel Alcubierre’s 1994 paper, the first to examine the distortion of spacetime as a driver for a spacecraft, to discover that such a drive would demand amounts of energy beyond anything available in the known universe. And that was only the beginning. Alcubierre’s work demanded positive energy to contract spacetime in front of the vessel and negative energy to expand spacetime behind it. Given that we do not know whether negative energies densities can exist, much less be manipulated by humans, the work remained completely theoretical.

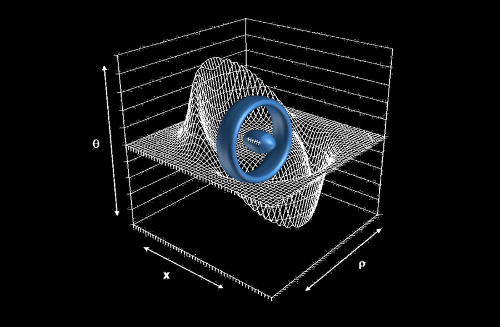

Image: A starship (in the center of the ring) taking advantage of the distortion of spacetime. Credit: Harold White.

But interesting things have developed since the original Alcubierre paper. Running quickly through what White told the Houston audience, Chris van Den Broeck was able to reduce the energy costs of a warp drive significantly and other theorists have continued to drop the numbers. White’s team has been examining ways to continue that progression, but what is eye-catching is that he is working on a laboratory experiment to “perturb spacetime by one part in ten million” using an instrument called the White-Juday Warp Field Interferometer to create the minute spacetime disruption.

I know of no teams other than White’s who are looking at lab work that could tell us whether a perturbation of spacetime can actually be created. From a NASA document on this work:

Across 1cm, the experimental rig should be able to measure space perturbations down to ~1 part in 10,000,000. As previously discussed, the canonical form of the metric suggests that boost may be the driving phenomenon in the process of physically establishing the phenomenon in a lab. Further, the energy density character over a number of shell thicknesses suggests that a toroidal donut of boost can establish the spherical region. Based on the expected sensitivity of the rig, a 1cm diameter toroidal test article (something as simple as a very high-voltage capacitor ring) with a boost on the order of 1.0000001 is necessary to generate an effect that can be effectively detected by the apparatus. The intensity and spatial distribution of the phenomenon can be quantified using 2D analytic signal techniques comparing the detected interferometer fringe plot with the test device off with the detected plot with the device energized.

So it’s interesting stuff, and it takes us to an even lower energy requirement, from the mass-energy of a planet the size of Jupiter to, in White’s view, a mass about the size of one of our Voyager probes. The reduction in the exotic matter/negative pressure required is managed by optimizing the warp bubble thickness and also by oscillating the bubble intensity, which according to White’s mathematics reduces the stiffness of spacetime. Thus we go from a Jupiter-sized portion of exotic matter to an amount weighing less than 500 kg.

White said the test was an attempt to prove that spacetime perturbation is possible, and likened it to a ‘Chicago pile moment.’ It was in 1942 that the first demonstration of a controlled nuclear reaction produced just half a watt of power, but a year later a four megawatt reactor was already in operation. With no tidal forces inside the warp bubble and a proper acceleration of zero, a future craft would be an undemanding platform in which to travel, and White pointed out that clocks aboard the spacecraft would move at the same rate as clocks back on Earth. It’s an exotic idea, but one that White’s lab testbed will now poke and prod to see if it’s possible.

Addendum: Al Jackson just sent me an email about other matters, but it includes a portion that’s specifically related to the above topic that I want to quote:

“I did my doctorial stuff in General Relativity. When I was in Austin for Armadillocon, last August, I asked my adviser, Richard Matzner, about the Alcubierre deal, since Richard does a lot of numerical GR he knows Alcubierre (who is an ace numerical GR guy), says he never heard him talk about his warp drive. Richard is not much interested in it either, thinks the solution is Lyapunov unstable. I have seen some works from Italy about Alcubierre and other ‘exotic matter’ warp solutions that show the models are unstable. Richard said he thinks Kip Thorne is no longer interested in it. I have never seen a really ‘heavy hitter’ like Hawking or Thorne, or a whole lot of other first string GR theorists ever remark on Alcubierre or the other recent solutions. There was a ‘name’ relativistist, William A. Hiscock, who did, he felt the solutions were not physical, but he thought people should keep trying. Alas that guy died young, only a few years ago.

But it is interesting that these solutions exist. I think, it’s going to take more imagination and further discoveries before something can be made of this.”

Saturday at the 100 Year Starship Symposium

While I didn’t see too many technical glitches at the 100 Year Starship Symposium in Houston, I ran into plenty of them in my own attempts to cover the event. The banquet hall where the opening ceremonies were held — and where the plenary sessions occurred each day — was impervious to the hotel’s WiFi, so that I was unable to use Twitter. Friday’s technical sessions in the conference rooms went fine, and I managed to send out a steady stream of tweets from the ‘Time and Distance Solutions’ track. But halfway through the Saturday sessions, Twitter itself went down. I tried all afternoon to get on, but though my Net connection was strong, Twitter wouldn’t come up.

Image: Early arrivals setting up at the opening plenary session for the 100 Year Starship Symposium. Everything in order but the WiFi.

My experience with US Airways was about the same. The two flights out to Houston were uneventful, but coming back I was on an aircraft that reached new levels of passenger compression. With my knees hard up against the seat in front of me and that seat tilted back to maximum extent into my face, I could only close my eyes and pretend I was someplace else. We’ve all gone through things like this on packed flights, but I was reminded again why I have my 1000-mile rule. If a trip is anything less than 1000 miles, I’m going by rail or car. Period.

The Saturday science sessions were top-notch (congratulations to track chairman Eric Davis for his excellent work throughout the conference). Joe Ritter (University of Hawaii) gave an eye-opening talk about metamaterials, which he believes can reduce the cost of telescope fabrication by a factor of 100. This is heartening given the need to deploy big mirrors in space to look for and analyze exoplanet atmospheres. Joe’s team is looking at mirrors with what he describes as ‘photonic muscle,’ material that minimizes ambient light and can respond actively to conditions. Think of today’s adaptive optics extended in entirely new directions and available in ultralight models. A Hubble size mirror using some of these materials would weigh just 1 pound.

If you’re thinking not just of ground- or space-based telescopes but of starships, Joe’s huge, lightweight mirrors could be the basis of communication systems. For that matter, metamaterials like these can become involved in power generation and thermal regulation. There are even solar sail possibilities. In many ways the mission architectures becoming available to us will depend upon the advances in materials technology that this kind of work represents.

Vince Teofilo (Energy Innovations) ran through a conceptual design for a starship ark that he has been working on for the Space Colony Earth project, which involves repositories on Earth, the Moon and a starship that are seen as ways of preserving digital data and human DNA information. What Space Colony Earth has in mind is guarding against mass extinctions of the kind that felled the dinosaurs. A robotic long-haul starship of the kind Vince described would target a star with an Earth-like planet and would include experiments to be run en-route to provide data for future, faster interstellar missions. Among the propulsion options are an inertial electrostatic confinement space thruster developed by George Miley (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign), though Vince examined a range of alternatives.

Image: The view from outside my 19th floor room at the Hyatt Regency. An MD friend of mine, back in the days when this kind of hotel design was just coming in, looked up at such a scene at a conference and exclaimed “This is Babylon!” Well not quite, but the Hyatt was a good venue.

Icarus Interstellar was all over the science sessions, and the two I attended on Saturday covered recent work involving what the team is learning about the original Daedalus design. Robert Freeland (Podtrac), discussing a paper he did in conjunction with science fiction author Stephen Baxter, noted that the Daedalus team’s calculations had largely been validated, though some aspects were in need of a tune-up. Remember that Daedalus came out of the 1970s, its team working in loose association using slide rules and pencils rather than computers. Freeland described an early Icarus iteration that would reduce payload to 50 tons from Daedalus’ 450 thanks to advances in miniaturization, with an additional set of fuel tanks for each stage and full deceleration into the Alpha Centauri system. Mission time: just under 100 years.

You would think that an Alpha Centauri probe might swing by Proxima Centauri in some way on its way to Centauri A and B, but the scenario turns out to be surprisingly difficult to manage given the speeds involved on the way to the ultimate destination, as Freeland described. Splitting off a flyby probe targeting Proxima after the acceleration of the main probe is perhaps a possibility, but the primary probe still decelerates into the Centauri AB system, with the latter probe dividing into separate probes for the exploration of each star’s (assumed) planetary system.

Still up in the air are issues like inertial confinement fusion and whether it will become the final choice of the Icarus design team. The continuing work at the National Ignition Facility has shown how tricky it is to compress a fuel pellet with lasers symmetrically. A final, major question: How do you do a re-start if the system shuts down? The Daedalus Final Report did not address the problem, and the Icarus team will explore this along with the question of mis-fires and how they could damage the reaction chamber.

Image: Hard at work in the ‘Time and Distance Solutions’ track.

Pat Galea, who gave three papers on Icarus topics, presented his third in place of author Adam Crowl, who could not be in Houston. Crowl was looking at efficient braking mechanisms for an interstellar probe entering its destination system, wondering about the feasibility of magnetic sail braking in which an artificial magnetosphere interacts with the interstellar medium. The magnetosphere itself is created with a huge ring of superconducting wire attached to the vehicle. Magsails turn out to help reduce overall system mass significantly when compared to other methods in a Daedalus-class vehicle.

Finally, Rob Adams (MSFC) discussed the Decade Module Two (DM2) device his team is reassembling after its donation to the University of Alabama at Huntsville. Located at the UAH Aerophysics Laboratory at nearby Redstone Arsenal, the device was originally developed to model the effects of thermonuclear explosions, but can be productively put to work in a variety of fusion experiments ranging from magnetic nozzle tests to the simulation of a solar mass ejection. In a so-called Z-pinch, current applied to plasma by a large bank of capacitors creates a magnetic field that pinches the plasma into a small cylinder to reach fusion conditions. See Z-Pinch: Firing Up Fusion in Huntsville for more.

Image: Rob Adams describing the DM2 and its potential.

Can plasma explosions generated by the Z-pinch be directed into a flow of thrust of the kind that would drive a spacecraft? Fusion-pulsed propulsion may one day be practical, but it will take experiments with equipment like the DM2 to help us find out. All this work is obviously in the early stages of development and it won’t be until the spring of next year that high-power testing could begin, assuming the assembly continues to go well and funding is forthcoming. Adams noted that the DM2 facility will also be made available to outside experimenters.

Time and Distance in Houston

?

?

At left is Mae Jemison, snapped from my seat as she spoke to open yesterday morning’s sessions. I couldn’t tweet about her comments because the hotel Wi-Fi wasn’t working in the room. Several people asked me today why I was still using a ‘netbook’ to take notes and send out tweets from the Houston symposium. It’s an easy answer — I need a standard keyboard rather than a virtual one, and despite the beauty of tablets like the iPad, I don’t want to carry a separate keyboard around. Besides, my little 10-inch screen Asus serves me well, gives me all the connectivity I need, and runs Linux much faster than the original Windows that it came with (I blew Windows off the hard disk as soon as I bought it and slipped Ubuntu on effortlessly, continually updating it ever since). At $350, which is what it set me back a few years ago, the netbook is a no-brainer for places where I need to make a lot of notes, and if I leave it in a taxi or drop it, the financial loss is minuscule.

Image: Mae Jemison against a starry background yesterday morning, presenting a rousing call for an interstellar future.

Look for more tweets today just as yesterday. I keep playing around with methodologies, popping up notetaking windows and sometimes jotting things down on a paper pad, but in reality sending out tweets is one of the best ways for me to focus my attention on what a speaker is saying. There is a wide choice in tracks here, which has led to a lot of angst about missing good papers. I finally settled on ‘Time and Distance Solutions,’ but I keep wishing I could clone myself long enough to attend papers in some of the other tracks simultaneously. ‘Becoming an Interstellar Civilization’ is loaded with good presentations, as is ‘Destinations and Habitats,’ and there are other choices as well.

Claudio Maccone and I enjoyed a long, leisurely dinner (salmon and a decent New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc, though not the match of Cloudy Bay), but by the end of it, my back was letting me know it was time to shut down for the day (not good, because I had planned to go to the Icarus Interstellar party). Spending the entire day in a chair, thus missing my usual 3-5 mile walk and getting no other exercise, played havoc with my various disk problems, reminding me I’m not as young as I used to be. Even so, it was a good day yesterday, despite the hotel Wi-Fi balkiness. A lunch with the various teams that made proposals to the DARPA solicitation was appreciated, as each could give an overview of his or her concepts. Great to spend some time there with Gordon Gould, whose ideas on getting the word out about interstellar studies have resonated with me since Orlando.

I’ve also been meeting more and more Centauri Dreams readers, more than in Orlando, I think. What a pleasure to be able to put a face with a name, and I have to thank all who have taken the time to come up and introduce themselves. The papers I’ve heard have been strong, in particular Richard Obousy’s superb overview of breakthrough propulsion concepts, which was delivered with panache and good humor and helped me keep some of the more futuristic ideas in perspective. Kudos as well to Sonny White (JSC), Jeffrey Lee (Crescent School, Toronto) and Pat Galea for crisp, incisive work. Pat collaborated with Greg Matloff on a multi-century probe idea using nanotechnology and beamed sails, not the fastest route but a compelling design in which the nanotech payload is essentially painted onto the sail itself. Fascinating to imagine.

Image: Pat Galea speaking in the ‘Time and Distance Solutions’ track.

Jeremy Straub (University of North Dakota) did a fine job describing the kinds of autonomous systems that any interstellar probe will need, whether crewed by humans or not. I was put in mind of the old Daedalus idea of ‘wardens,’ robotic maintenance and repair systems that keep the craft in operation. Straub noted how useful it would be to mount a near-term mission to test the viability of autonomous systems at ever increasing time lengths. The Voyagers are classy craft, but an interstellar mission might go on not for 35 years but for centuries, and robotic systems have to have the flexibility and ability to learn that will allow them to deal with ever changing situations. Focusing on autonomy and heuristics, this is one precursor mission that could have near-term consequences at advancing the state of the art.

Houston: Meetings and Reconnections

?Bring an umbrella to Houston? I figured it would be unnecessary and left it out of my luggage. Lo and behold yesterday morning it began to rain and it seems to have continued off and on most of the day. That hardly matters when you’re in a huge high-rise hotel, but it’s a good thing it didn’t happen Wednesday night, when I walked all over downtown looking for restaurants. I favor inexpensive ethnic places with interesting menus but also love any place with a decent wine list and crusty bread baked in-house. I walk 3-5 miles each day and get seriously stressed out when I don’t get in the exercise, so I’m hoping the rain will be gone or at least sporadic enough today to let me get out a bit. Houston’s humidity, I must say, did slow down my pace in each journey I’ve taken so far.

No time for walking yesterday, though, as I spent all day in meetings re the 100 Year Starship organization and future planning. It was great fun to be with a small group including 100 Year Starship leader Mae Jemison, Jill Tarter and LeVar Burton talking about interstellar issues. Burton, Star Trek’s Geordie LaForge, is as persuasive and eloquent an interstellar advocate as I’ve ever encountered, a man who deeply believes in the kind of future the Federation represented in the series. He thinks we have the chance to evolve technology and human ethics in the direction the show portrayed. About Jill Tarter, what can I say other than that it was a pleasure to see her again and benefit from her numerous insights. We are clearly not far from the day, thanks to Kepler, that we find a true Earth analogue, an Earth-mass planet in the habitable zone around a Sun-like star.

Image: Claudio Maccone, Jill Tarter and myself at a 100 Year Starship Symposium party.

Ecuadoran student Juan Robalino (now studying in Vienna) re-connected after our conversations last year in Orlando, and was kind enough to bring me an Ecuadoran Montecristi hat as a souvenir. Then dinner last night with my buddy Al Jackson, who found yet another way to pick up the check — I may have to handcuff him next time to pay for his dinner. Al still lives in Houston following his years with NASA and the Apollo program. The beauty of Al is that there seems to be no science fiction novel — indeed, no science fiction short story — he hasn’t read. So we play a game of origins. Which science fiction writer came up with the first antimatter drive, and where was it published? (We’re still kicking that one around). How much of a hand did John Campbell have in shaping Frank Herbert’s Dune? (Maybe more than suspected). Who portrayed Einsteinian time dilation in science fiction for the first time? (Robert Wilson in ‘Out Around Rigel’). All of this kindles my love of old books and magazines and we revel in the glory days of Heinlein and Asimov.

Al told me that in the Apollo days, surprisingly enough, there were few SF readers among the scientists and engineers in Houston. Nowadays, SF readers are common at NASA centers and elsewhere. What happened? I have no idea, but maybe that earlier generation had focused largely on the science itself because the fiction seemed too implausible. But today, having seen the Moon landings and thirsty for more, several generations have come of age that cut their teeth on science fiction. When I was researching my Centauri Dreams book, scientist after scientist reminisced about growing up reading Heinlein, Asimov and Clarke. And I’ve mentioned more than a few times here that the book singled out more than any other by these scientists was Anderson’s Tau Zero. The current wave of so-called ‘hard’ science fiction may play a similar role in inciting younger students to follow up interests in astronomy, astronautics and aerospace.

Dinner also offered the chance to talk to the multi-talented Shen Ge, co-founder and president of a group called Scientific Preparatory Academy for Cosmic Explorers (SPACE). Rather than trying to explain the vision Shen has for bringing astronautics into education, I’ve asked him to put together an article on his concept for publication on Centauri Dreams. Both Shen and fellow dinner guest Doug Yazell write for the Houston branch of the American Institute of Aeronautics & Astronautics, and I assume we’ll be seeing 100 Year Starship coverage in their publication. Our conversation over a good bottle of Bouchaine Pinot Noir was a superb finale to the day.

Earlier, at a symposium party, I had the chance to see Claudio Maccone, whose gravitational lens mission called FOCAL plays an interesting role in David Brin’s new novel Existence (yet one more reason to read this fine book). Claudio is one of the great gentlemen of interstellar studies, unfailingly courteous to a fault and willing to explain to a mathematics-challenged writer like me concepts as abstruse as KLT, the Karhunen–Loève Transform. I can’t say I fully understand Claudio’s work on KLT but at least I know what he’s trying to do with it, and can see why he thinks it could be an interesting SETI tool as well as a possible way to sort out tricky exoplanet signatures. The FOCAL mission, of course, is something I’ve written about here on many occasions, a chance to use the huge magnifications available at distances beyond 550 AU from the Sun.

I’ll try to get out some tweets about sessions today. Wasn’t able to do it yesterday.

Addendum: Yesterday I pointed to the wrong link for Kelvin Long’s new Institute for Interstellar Studies. This link should correct that.

A Stellar Thursday in Texas

?A few words before a long day begins. I’m in meetings all Thursday here in Houston as the 100 Year Starship Symposium gets going, having slept well last night on the gigantic bed provided by the Hyatt. The travel day was uneventful. I had decided to make this a non-digital flight as much as possible so as to get through security with less difficulty. That meant the laptop went in a checked bag, the Kindle stayed home, and for the plane I took an actual book, one with pages that you turn by hand, a cover, and an index in place of a search engine. So much for my plans – everything was going great until a couple of coins in my pocket set off the alarms and I got patted down.

Image: Yesterday afternoon’s view from my room. The Hyatt Regency has a rotating restaurant on its 31st floor. Despite Calvin Trillin’s famous exhortation never to eat in a restaurant that rotates, I found the food quite good, including a spectacular glass of Cloudy Bay Sauvignon Blanc from New Zealand. Nice view, too.

I’m seeing articles about the symposium popping up here and there in the media, maybe not so many as last year, although I haven’t had the chance to quantify it yet. One common misapprehension continues to be what the 100 Year Starship organization is really about. The Daily Mail refers to a “dramatic plan to transport humans beyond the solar system within 100 years,” but who knows whether starships, if we learn how to build them, will carry humans or sophisticated artificial intelligence? Some people I’ve spoken with think the plan is to reach another star by 2112, but if we were going to get to another planetary system in 100 years, we would be launching the starship about now, and we obviously don’t have the capability of doing that. A lot of education has to be part of any starship organization, given the confusion about actual distances and how long it will take to understand the solutions.

I’m told that Kelvin Long’s Interstellar Studies Institute is about to go online, clearly timed for the 100 Year Starship Symposium, and that may help generate a bit of extra buzz as well. I hope that whatever comes out of the press attention to this event is part of a gradual process of getting interstellar ideas out to the public in a way that’s both inspirational but also realistic. Yes, there are ways using known physics that an interstellar journey can be done, assuming we develop the technologies that look theoretically possible and the infrastructure to support them. We’re nowhere near that level now, though maybe we can be ready to launch a star mission in a hundred years. Maybe. An email I got just before leaving lays out the level of misunderstanding: “We’re already going to Pluto,” says the writer. “ How much harder can it be to go to a star?”

I could write a whole book in answer to that question. Wait — I already have…