Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

The Latest from New Horizons

New Horizons is, like the two Voyagers, a gift that keeps on giving, even as it moves through the Kuiper Belt in year 17 of its mission. Thus the presentations that members of the spacecraft team made on March 14 at the 54th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Papers will flow out of these observations, including interpretations of the twelve mounds on the larger lobe of Arrokoth, the contact binary that is being intensely studied through stereo imaging to identify how these features formed around a larger center mound. Alan Stern (SwRI) is principal investigator for the New Horizons mission:

“We discovered that the mounds are similar in many respects, including their sizes, reflectivities and colors. We believe the mounds were likely individual components that existed before the assembly of Arrokoth, indicating that like-sized bodies were formed as precursors to Arrokoth itself. This is surprising, and a new piece in the puzzle of how planetesimals – building blocks of the planets, like Arrokoth and other Kuiper Belt objects come together.”

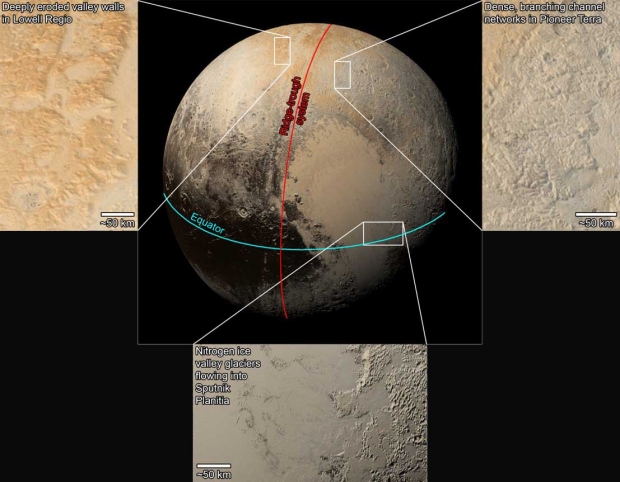

Science team members also discussed the so-called ‘bladed terrain,’ evidently the product of methane ice, that seems to stretch across large areas of Pluto’s ‘far side,’ as observed during the spacecraft’s approach. It was intriguing to learn as well about the spacecraft’s observations of Uranus and Neptune, which will complement Voyager imaging at different geometries and longer wavelengths. And Pluto’s ‘true polar wander’ (the tilt of a planet with respect to its spin axis came into play (and yes, I do realize I’ve just referred to Pluto as a ‘planet’). Co-investigator Oliver White:

“We’re seeing signs of ancient landscapes that formed in places and in ways we can’t really explain in Pluto’s current orientation. We suggest the possibility is that they formed when Pluto was oriented differently in its early history, and were then moved to their current location by true polar wander.”

Image: Pluto’s Sputnik Planitia, the huge impact basin found in Pluto’s ‘heart’ region, seems to have much to do with the world’s axial tilt, while the possibility of a deep ocean pushing against the basin from below has to be taken into account. This image is from the presentation by Oliver White (SETI Institute) at LPSC. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/SwRI/James Tuttle Keane.

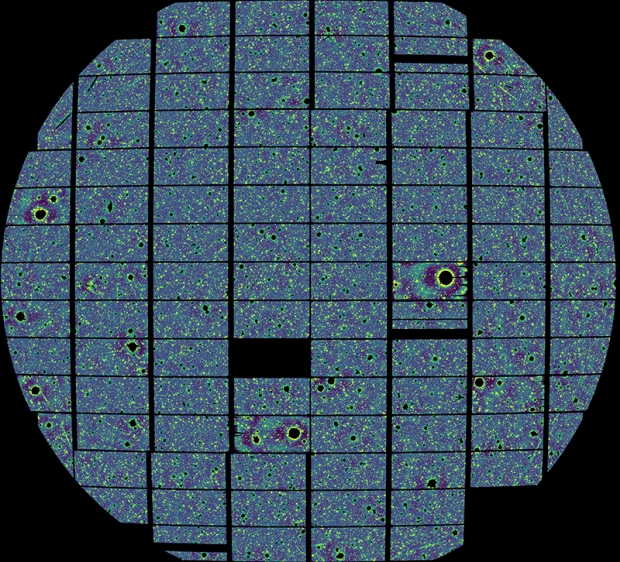

But let me pause today on the quest for other Kuiper Belt Objects as the search for a second flyby candidate continues. Not that a flyby is essential. Using the Japanese Subaru Telescope in Hawaii and the Victor M. Blanco instrument at Cerro Tololo, the team is now applying a deep learning algorithm (a ‘convolutional neural network’) to analyze imagery. Wes Fraser, a member of the science team, is quoted on the New Horizons site as saying “The software network’s classification performance is extremely good, significantly cutting back on ‘false’ candidate sources. An entire night’s worth of search data requires only a few hours of human vetting. Compare that to the weeks it used to take to do this!”

Image: A “stack” of images from one night of observing with the Subaru Telescope’s Hyper Suprime-Cam, showing myriad stars that illustrate the difficulty of spotting an undiscovered Kuiper Belt object. The animation below shows movement – across the center-right of the frame — of a newly discovered KBO in one of these images. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Southwest Research Institute/Subaru Telescope.

The point is that we’re learning a great deal about KBOs even in the absence of another flyby, discovering a surprising number of objects like that shown (look carefully) in the animation below. The Subaru Telescope produced, with its wide field of view, some 87 new KBOs in 2020 in the direction of the spacecraft’s trajectory. It was heartening to learn that running that same data through the new software enabled a search that was both 100 times faster but also revealed another 67 KBOs. Some of these – and about 20 will be close enough to observe from a distance of millions of miles – should be grist for the mill as New Horizons examines them in the coming two years.

Image: This animation shows movement—across the center-right of the frame—of a newly discovered Kuiper Belt object in one of the Subaru Telescope Hyper Suprime-Cam images. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Southwest Research Institute/Subaru Telescope.

Will JHU/APL’s Interstellar Probe design eventually be approved and join the spacecraft now departing our Solar System? Or will JPL’s Solar Gravity Lens mission to the gravitational focus become our next deep space sojourner? As we ponder mission designs and the likelihood of their approval, keeping an eye on our existing assets in deep space reminds us of the outstanding science return we’ve achieved thus far.

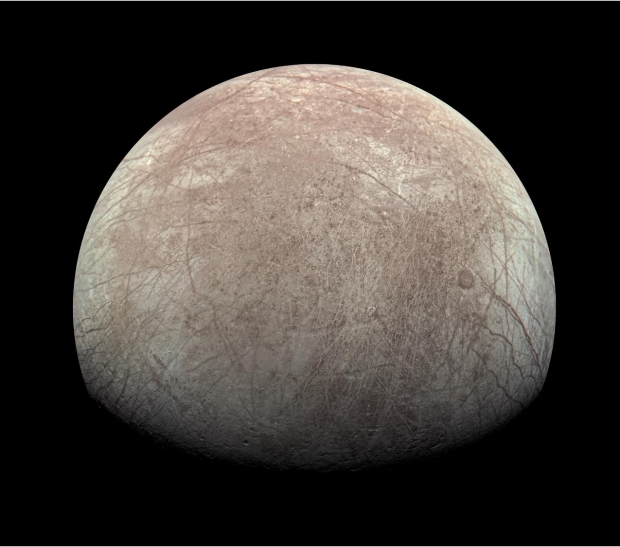

Oceanic Surprise: Pushing Europa’s Ice

Getting Europa Clipper to its target to analyze the surface of Jupiter’s most interesting moon (in terms of possible life, at least) sets up a whole range of comparative studies. We have been mining data for many years from the Galileo mission and will soon be able – at last! – to compare its results to new images pulled in by Europa Clipper’s flybys. Out of this comes an interesting question recently addressed by a new paper in JGR Planets: Is Europa’s ice shell changing in position with time?

An answer here would establish whether we are dealing with a free-floating shell moving at a different rate than the salty ocean beneath. Computer modeling has previously suggested that the ocean’s effects on the shell may affect its movement, but this is evidently the first study that calculates the amount of drag involved in this scenario. Ocean flow may explain surface features Galileo revealed, with ridges and cracks as evidence of the stretching and straining effects of currents below.

Hamish Hay (University of Oxford) is lead author of the paper on this work, which was performed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory during his postdoctoral tenure there. The study reveals a net torque on the ice shell from ocean currents moving as alternating east-west jets, sometimes spinning up the shell and at other times spinning it down as convection is altered by the evolution of the moon’s interior. Says Hay:

“Before this, it was known through laboratory experiments and modeling that heating and cooling of Europa’s ocean may drive currents. Now our results highlight a coupling between the ocean and the rotation of the icy shell that was never previously considered.”

Thus we are forced to reconsider some old assumptions, one of them being that the primary force acting on Europa’s surface is the gravitational pull of Jupiter. The paper calculates that an average ‘jet speed’ of at least ~1 cm s-1 produces enough ice-ocean torque to be comparable to tidal torque. Calling these results “a huge surprise,” Europa Clipper project scientist Robert Pappalardo (JPL) notes that thinking about ocean circulation as the driver of surface cracks and ridges takes scientists in a new direction: “[G]eologists don’t usually think, ‘Maybe it’s the ocean doing that.’”

Image: This view of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa was captured by JunoCam, the public engagement camera aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft, during the mission’s close flyby on Sept. 29, 2022. The picture is a composite of JunoCam’s second, third, and fourth images taken during the flyby, as seen from the perspective of the fourth image. North is to the left. The images have a resolution of just over 1 to 4 kilometers per pixel. As with our Moon and Earth, one side of Europa always faces Jupiter, and that is the side of Europa visible here. Europa’s surface is crisscrossed by fractures, ridges, and bands, which have erased terrain older than about 90 million years. Credit: NASA, with image processing by citizen scientist Kevin M. Gill.

It was the introduction of drag into the simulations that demonstrated the effects of ocean currents on the shell’s rotational speed. The under-ice flow depicted in this paper is complex, with supercomputing modeling showing water flow being bent by Europa’s overall rotation into east-west and west-east currents. The results depend upon a model of internal heating from radioactive decay as well as tidal heating to drive warmer water to the top of the ocean. They imply changes to the surface over time as the amount of interior heating varies, a process that presumably would occur on other ocean worlds as well.

The paper notes another aspect of the drag model that is unusual:

We have for the first time estimated the time-mean stress field and resulting torque that must exist between the flowing ocean and solid ice shell of Europa. Perhaps unintuitively, the stress field due to alternating zonal jets does not necessarily cancel out once integrated over the entire surface. This means that it is likely that ocean dynamics that manifest in east-west jets exert a net unidirectional torque on the ice shells of Europa and other ocean worlds.

Moreover, ice-ocean torque is a process whose effects can change dramatically. Notice the reversal process described below. The ‘equatorial jet’ mentioned here is accompanied in the simulations by one to two alternating jets at higher latitudes:

The scaling analysis shows that strengthening of turbulent convection reverses the equatorial jet and resulting torque such that it acts against the direction of rotation. The reversal occurs when the thermal buoyancy forcing becomes large enough to drive highly turbulent convection. If the energetic state of Europa’s interior has changed sufficiently over time, perhaps due to the depletion of radioactive heat producing elements or changes in tidal forcing, it is possible that a reversal has taken place. We speculate that this provides a novel mechanism to stop, start, and even reverse nonsynchronous rotation of the ice shell.

So we see the ice shell’s rotation being speeded up and at other times slowed down by the ocean currents below, sometimes stretching and at other times collapsing, with possible effects on surface topography that Europa Clipper can examine. How interesting that we can learn about the dynamics of the ocean below through the speed of the shell’s rotation, which is something the mission may be able to measure. The craft, now in assembly, test, and launch operations phase at JPL, is on target for a launch in 2024. Orbital operations at Jupiter begin in 2030, with some 50 Europa flybys on the schedule.

The paper is Hay et al., “Turbulent Drag at the Ice-Ocean Interface of Europa in Simulations of Rotating Convection: Implications for Nonsynchronous Rotation of the Ice Shell,” JGR Planets 19 February 2023 (full text).

Tracing Water through the Stages of Planet Formation

The presence of water in the circumstellar disk of V883 Orionis, a protostar in Orion some 1300 light years out, is not in itself surprising. Water in interstellar space is known to form as ice on dust grains in molecular clouds, and clouds of this nature collapse to form young stars. We would expect that water would be found in the emerging circumstellar disk.

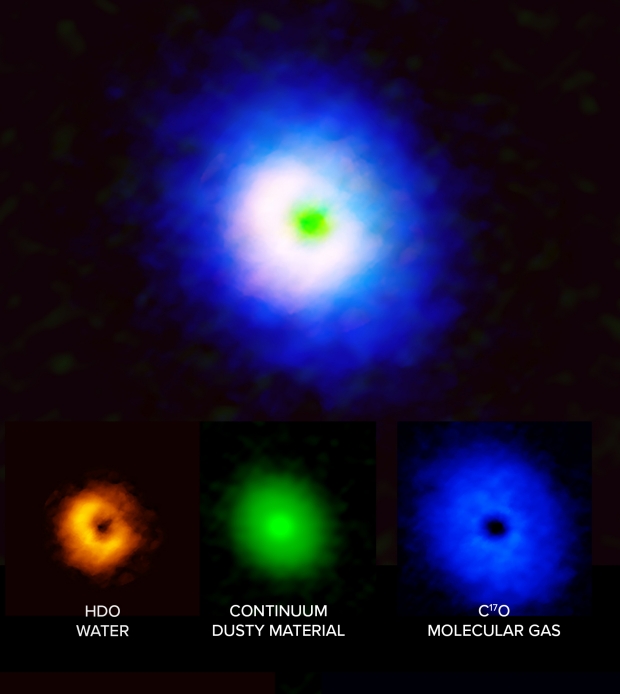

What new work with data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) shows is that such water remains unchanged as young star systems evolve, a chain of growth from protostar to protoplanetary disk and eventually planets and water-carrying comets. John Tobin, an astronomer at the National Science Foundation’s National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), is lead author on the paper on this work:

“We can think of the path of water through the Universe as a trail. We know what the endpoints look like, which are water on planets and in comets, but we wanted to trace that trail back to the origins of water. Before now, we could link the Earth to comets, and protostars to the interstellar medium, but we couldn’t link protostars to comets. V883 Ori has changed that, and proven the water molecules in that system and in our Solar System have a similar ratio of deuterium and hydrogen.”

Image: While searching for the origins of water in our Solar System, scientists homed in on V883 Orionis, a unique protostar located 1,305 light-years away from Earth. Unlike with other protostars, the circumstellar disk surrounding V883 Ori is just hot enough that the water in it has transformed from ice into gas, making it possible for scientists to study its composition using radio telescopes like those at the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). Radio observations of the protostar revealed water (orange), a dust continuum (green), and molecular gas (blue) which suggests that the water on this protostar is extremely similar to the water on objects in our own Solar System, and may have similar origins. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), J. Tobin, B. Saxton (NRAO/AUI/NSF).

V883 Ori is interesting in its own right as a star undergoing a so-called ‘accretion burst,’ a rarely observed occurrence in which a star in the process of formation ingests a huge amount of disk material, forcing an increase in its luminosity. Water reaches its condensation temperature at the ‘snow line,’ but finding the water snow line in a protoplanetary disk isn’t easy because for emerging stars similar to the Sun, it usually occurs as close as 5 AU, making the signal difficult to tease out through the dusty disk.

But V883 Ori has a disk massive and warm enough to allow these ALMA observations to distinguish the demarcation. The star masses 1.3 times the mass of the Sun, with a snow line now measured to have a radius of approximately 80 AU. Water is detected out to a radius of 160 AU according to the paper on this work, which recently appeared in Nature.

The water snow line is significant because water has much to do with the efficiency of early planetesimal formation as well as comets, not to mention its role in ice giants and gas giant cores. As we probe planet formation, we can also consider the implications of V883 Ori’s accretion burst, which raises the prospect that young stars in this stage of activity have water snow lines that can be highly dynamical, as a 2016 paper on V883 Ori points out (citation below). The new work finds gas phase water at a distance comparable to our own Kuiper Belt, with a composition that shows it remains unchanged through the stages of stellar system formation.

Merel van ‘t Hoff (University of Michigan) is a co-author on the 2023 paper:

“This means that the water in our Solar System was formed long before the Sun, planets, and comets formed. We already knew that there is plenty of water ice in the interstellar medium. Our results show that this water got directly incorporated into the Solar System during its formation. This is exciting as it suggests that other planetary systems should have received large amounts of water too.”

The paper is Tobin et al., “Deuterium-enriched water ties planet-forming disks to comets and protostars,” Nature 615 (08 March 2023), 227-230 (abstract). See also Cieza et al., “Imaging the water snow-line during a protostellar outburst,” Nature 535 (13 July 2016), 258–261 (abstract).

How a Super-Earth Would Change the Solar System

If there is a Planet Nine out there, I assume we’ll find it soon. That would be a welcome development, in that it would imply the Solar System isn’t quite as odd as it sometimes seems to be. We see super-Earths – and current thinking seems to be that this is what Planet Nine must be – in other stellar systems, in great numbers in fact. So it would stand to reason that early in its evolution our system produced a super-Earth, one that was presumably nudged into a distant, eccentric orbit by gravitational interactions.

The gap in size between Earth and the next planet up in scale is wide. Neptune is 17 times more massive than our planet, and four times its radius. Gas giant migration surely played a role in the outcome, and when considering stellar system architectures, it’s noteworthy as well that all that real estate between Mars and Jupiter seems to demand something more than asteroidal debris. To make sense of such issues, Stephen Kane (University of California, Riverside) has run a suite of dynamical simulations that implies we are better off without a super-Earth anywhere near the inner system.

Image: Artist’s concept of Kepler-62f, a super-Earth-size planet orbiting a star smaller and cooler than the sun, about 1,200 light-years from Earth. What effect would such a planet have in our own Solar System? Image credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/Tim Pyle.

Supposing a super-Earth did exist between Mars and Jupiter, Kane’s simulations demonstrated the outcomes for a range of different masses, the results presented in a new paper in the Planetary Science Journal. The heavyweight of our system, Jupiter’s 318 Earth masses carry profound gravitational significance for the rest of the planets. Disturb Jupiter, these results suggest, and in some scenarios the inner planets, including our own, are ejected from the Solar System. Even Uranus and Neptune can be affected and perhaps ejected as well depending on the super-Earth’s location.

As the paper notes, the range of possibilities is wide:

…several thousand simulations were conducted, producing a vast variety of dynamical outcomes for the solar system planets. The inner solar system planets are particularly vulnerable to the addition of the super-Earth planet, resulting in numerous regions of substantial system instability. The broad region of 2–4 au contains many locations of MMRs [Mean Motion Resonances] with the inner planets that further amplify the chaotic evolution of the inner solar system. There are also important MMR locations with the outer planets within the 2–4 au region, with potential significant consequences for the ice giants.

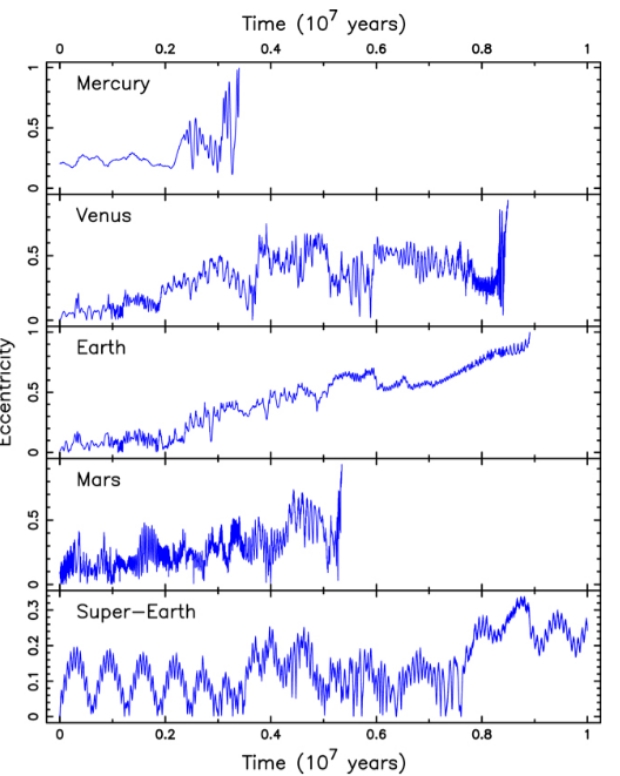

Let’s look at one possible outcome. The figure below shows the evolution in the eccentricity of the orbits of the inner planets in our Solar System, assuming a super-Earth with a mass of 7 times Earth’s and a semi-major axis of 2 AU. The simulation covers 107 years.

Image: This is Figure 2 from the paper. Caption: Eccentricity evolution of the solar system terrestrial planets (top four panels) for a 107 yr simulation, where the additional planet (bottom panel) has a mass and semimajor axis of 7.0 M? and 2.00 au, respectively. Credit: Stephen Kane.

The results show the devastating disruption this scenario produces. The orbits of the four inner planets become unstable over time, removing all of them from the system before the simulation concludes. Mars gets knocked out halfway through the simulation period, while Mercury is ejected early due to interactions with Venus and the Earth. The latter two planets see a gradual increase in their eccentricities. The semimajor axis of Venus increases as it decreases for Earth, creating close encounters and removing both worlds from the system 8 to 9 Myr after the simulation starts.

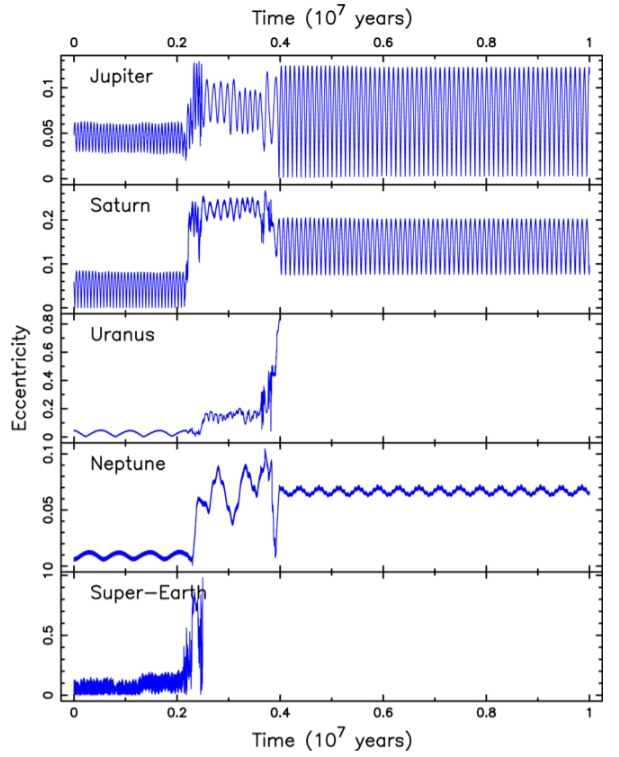

Different things happen, of course, as Kane manipulates the variables. Assuming a super-Earth with a mass eight times the Earth’s at 3.7 AU, the surprising result (surprising to me, at least) is that Mars remains largely unaffected, while it’s the super-Earth whose interactions with the outer planets become intense. The orbits of Venus and Earth begin to become more eccentric, with perturbations to the orbit of Mercury that eventually remove it from the system entirely. It’s fascinating to work through this paper to examine the various scenarios. Take a look at yet another possibility:

Image: This is Figure 8. Caption: Eccentricity evolution of the solar system outer planets (top four panels) for a 107 yr simulation, where the additional planet (bottom panel) has a mass and semimajor axis of 7.0 M? and 3.80 au, respectively. Credit: Stephen Kane.

Here we get Mean Motion Resonances with Jupiter and Saturn after about two million years, increasing the eccentricity of both, with the super-Earth ultimately being ejected from the system. Uranus is lost after about 4 million years and Neptune undergoes significant changes to its eccentricity. As Kane notes, the simulations show changes to system dynamics that are hugely sensitive to initial conditions, and in cases where significant interactions occur in the outer system, the orbits of the inner planets tend to become unstable as well. In the case of Figure 8, Mars is eventually ejected.

And this may have some bearing on our search for Planet Nine:

…the initial orbit for the additional planet was coplanar with Earth. Mutual inclinations between planetary orbits plays a role in overall system stability (Laskar 1989; Chambers et al. 1996), particularly for large inclinations (Veras & Armitage 2004; Correia et al. 2011), and may provide solutions to otherwise unstable architectures (Kane 2016; Masuda et al. 2020). It is therefore possible that there are orbital inclinations for the super-Earth that may reveal further locations of long-term stability, or else enhance unstable scenarios…

The paper implies, as the author adds in his conclusion, the “dynamical fragility” of the Solar System we have, with applications for the study of exoplanetary system architectures. How systems manage to work out sharing arrangements with super-Earths will doubtless become a key question for research as we move further into the era of space-based astrometry and learn more about how systems evolve.

The paper is Kane, “The Dynamical Consequences of a Super-Earth in the Solar System,” Planetary Science Journal Vol. 4, No. 2 (28 February 2023) 38 (full text).

DART’s Ejecta and Planetary Defense

I’m glad to see the widespread coverage of the DART mission results, both in terms of demonstrating to the public what is possible in terms of asteroid threat mitigation, and also of calming overblown fears that we have too little knowledge of where these objects are located. DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) was a surprisingly demonstrative success, shortening the orbit of the satellite asteroid Dimorphos by an unexpectedly large value of 33 minutes. The recoil effect from the ejection of asteroid material, perhaps as high as 0.5% of its total mass, accounts for the result.

Watching the ejecta evolve has been fascinating in its own right, as the interactions between the two elements of the binary asteroid come into play along with solar radiation pressure. Asteroids have previously been observed that displayed a sustained tail, as Dimorphos did after impact, and the DART results suggest that the hypothesis of similar impacts on these objects is correct. Thus we learn valuable lessons about how asteroids behave when impacted either by technologies or by natural objects. We can expect the study of ‘active asteroids’ to get a boost from the success of this mission.

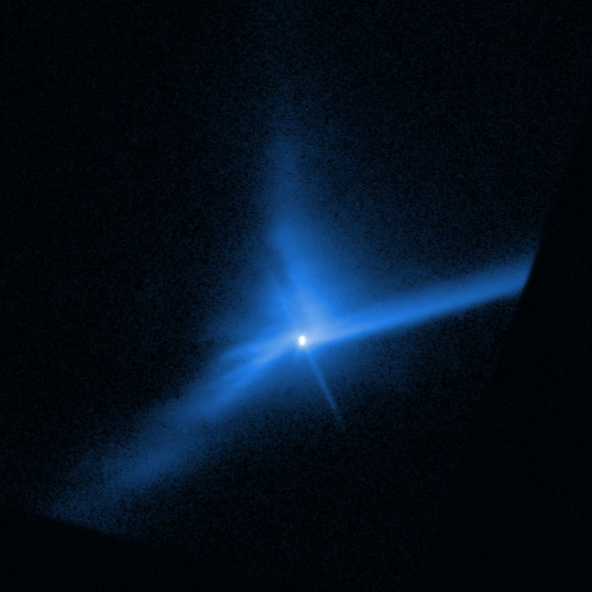

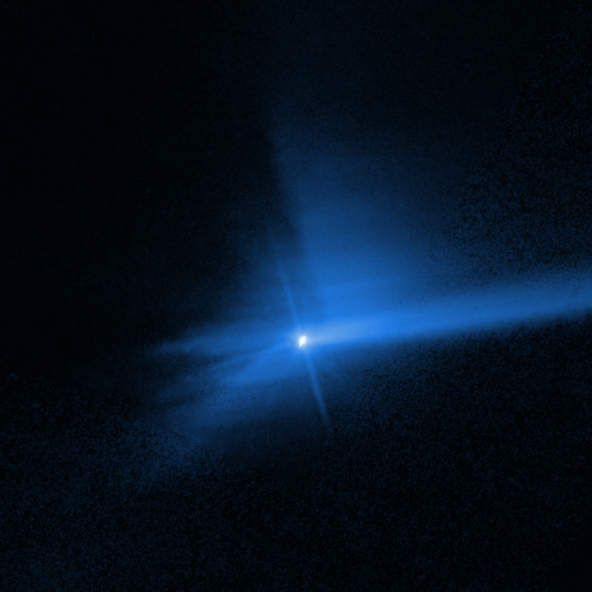

The two images below are from the Hubble instrument, which observed the development of Dimorphos’ tail. Jian-Yang Li (Planetary Science Institute) is lead author of a recent paper in Nature on the evolution of the ejecta. Li comments on the interplay between the gravity of Dimorphos and parent asteroid Didymos as well as the pressure of sunlight in the first two and a half weeks after the impact. Bear in mind that an impact on a single as opposed to a binary asteroid would not display such complex effects. The presence of Didymos was indeed useful:

“A simple way to visualize the evolution of the ejecta is to imagine a cone-shaped ejecta curtain coming out from Dimorphos, which is orbiting Didymos. After about a day, the base of the cone is slowly distorted by the gravity of Didymos first, forming a curved or twisted funnel in two to three days. In the meantime, the pressure from sunlight constantly pushes the dust in the ejecta towards the opposite direction of the Sun, and slowly modifies and finally destroys the cone shape. This effect becomes apparent after about three days. Because small particles are pushed faster than large particles, the ejecta was stretched towards the anti-solar direction, forming streaks in the ejecta.”

Image: Ejecta from Dimorphos 4.7 days (above) and 8.8 days (below) after impact, taken on October 1 and October 5, 2022, respectively. The Sun is at the 8 o’clock direction. The ejecta is pushed by the sunlight towards the 2 o’clock direction and increasingly stretched to form streaks. Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, Jian-Yang Li (PSI), Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale.

So we’ve learned that slamming a 570 kilogram spacecraft into this type of asteroid at something over 22,000 kilometers per hour can alter its orbital speed. Data from the Light Italian CubeSat for Imaging of Asteroids (LICIACube) is part of the current analysis, while we’ll learn yet more about the effects of the impact from the European Space Agency’s Hera mission, which will survey both Didymos and Diomorphos, focusing on the crater left by DART and the changes to the mass of the impacted asteroid.

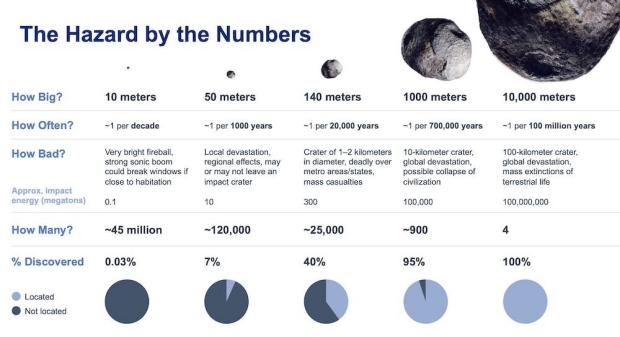

The matter of locating those hazardous asteroids that have yet to be identified is now highlighted by what we can consider the next planetary defense mission, the Near-Earth Object Surveyor, planned for a 2028 launch. The mission will carry a 50 centimeter diameter telescope operating at two infrared wavelengths, conducting a multi-year survey in search of near-Earth objects larger than 140 meters. The goal is to find 90 percent of such objects coming within 48 million kilometers of Earth’s orbit. The observation strategy employed should allow accurate enough determination of asteroid orbits to allow them to be found again and their trajectories tracked.

Image: Near-Earth asteroids and the possibilities of impact. Credit: NASA.

The paper on DART, one of five papers recently published in Nature on the mission, is Jian-Yang Li et al., “Ejecta from the DART-produced active asteroid Dimorphos,” Nature 01 March 2023 (abstract).

Re-thinking the Early Universe?

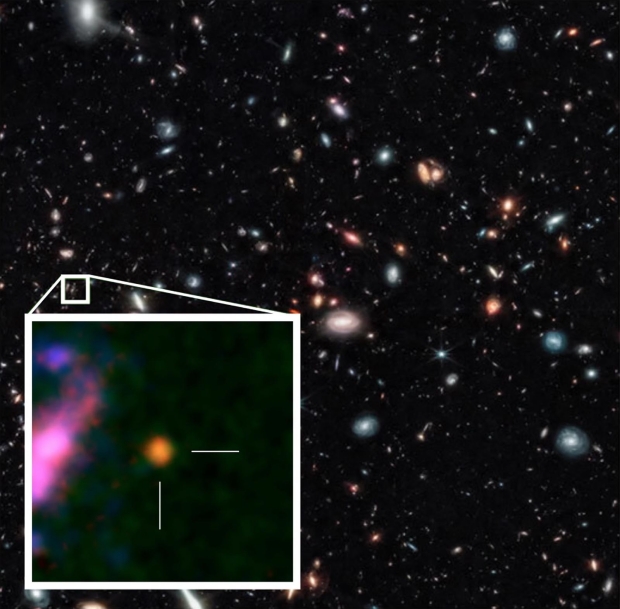

I hadn’t intended to return so quickly to the issue of high-redshift galaxies, but SPT0418-47 jibes nicely with last week’s piece on 13.5 billion year old galaxies as studied by Penn State’s Joel Leja and colleagues. In that case, the issue was the apparent maturity of these objects at such an early age in the universe.

Today’s work, reported in a paper in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, comes from a team led by Bo Peng at Cornell University. It too uses JWST data, in this case targeting a previously unseen galaxy the instrument picked out of the foreground light of galaxy SPT0418-47. In both cases, we’re seeing data that challenge conventional understanding of conditions in this remote era. This is evidence, but of what? Are we wrong about the basics of galaxy formation? Do we need to recalibrate the models we use to understand astrophysics at high-redshift?

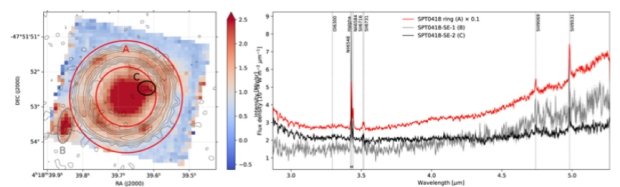

SPT0418-47 is the galaxy JWST was being used to study, an intriguing subject in its own right. This is an infant galaxy still forming stars in the early universe, observable through the bending of its light by a foreground galaxy to form an Einstein ring. In other words, we’re seeing gravitational lensing at work here, magnifying the young galaxy’s light, out of which information can be extracted about the primordial object. And within that light, astronomers have now found a second galaxy which manifested itself in two places in the ring.

Image: This is Figure 1 from the paper. Caption: Figure 1. Left: H? pseudo-narrowband image of the SPT0418 system, averaged over the channels including the H? emission in the original spectral cube. The strongly lensed ring and the two newly discovered sources (SE-1 and SE-2) are highlighted by a red annulus and gray and black ellipses, marked as “A,” “B,” and “C,” respectively. The lensing galaxy is shown as the central bright source. The 835 ?m continuum is plotted as the thin black contours, with the levels 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 × ? where ? = 56.7 ?Jy beam ?1. Right: the spectra of the three sources integrated over the regions highlighted in the left panel, using the same color scheme. The spectrum for the ring is scaled by a factor of 0.1 for clarity. The small black bar below the H? line marks the wavelength coverage of the pseudo-narrowband image. The potentially detected lines are marked by vertical dotted lines. Credit: The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2023). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/acb59c.

ALMA (the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) data could do no more than hint at the background galaxy’s existence, but working with spectral data from JWST’s NIRSpec instrument, Peng discovered the new light source within the Einstein ring. The unexpected find was a galaxy being gravitationally lensed by the same foreground galaxy that had made SPT0418-47 available for study, though considerably fainter.

What stands out here is the analysis of the chemical composition of the new galaxy’s light, which shows strong emission lines from hydrogen, nitrogen and sulfur atoms whose redshift showed the object to be about 10 percent of the age of the universe. The new galaxy, dubbed SPT0418-SE, appears to be close enough to SPT0418-47 that the two galaxies will interact with each other, making the duo a case study for galactic mergers. All of which is helpful, but here again we run into a fascinating problem. The newly discovered galaxy shows levels of metallicity comparable to our Sun.

It’s a conundrum. The Sun drew on earlier stellar generations to build up elements heavier than helium and hydrogen, and the Sun is roughly 4.6 billion years old. Amit Vishwas (Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Sciences) is second author on the paper:

“We are seeing the leftovers of at least a couple of generations of stars having lived and died within the first billion years of the universe’s existence, which is not what we typically see. We speculate that the process of forming stars in these galaxies must have been very efficient and started very early in the universe, particularly to explain the measured abundance of nitrogen relative to oxygen, as this ratio is a reliable measure of how many generations of stars have lived and died.”

But let’s turn back a minute, for we’re looking at two early galaxies, and it’s intriguing that SPT0418-47, the first of these, shows its own anomalies. Data from ALMA allow astronomers to see that although 12 billion years old, this object has a more mature structure than would be expected. No spiral arms are apparent, but a rotating disk and bulge are found, with stars packed tightly around the galactic center. Simona Vegetti (Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics), co-author on the 2020 paper on SPT0418-47 (citation below), had this to say three years ago:

“What we found was quite puzzling; despite forming stars at a high rate, and therefore being the site of highly energetic processes, SPT0418-47 is the most well-ordered galaxy disc ever observed in the early Universe. This result is quite unexpected and has important implications for how we think galaxies evolve.”

Image: Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), in which the European Southern Observatory (ESO) is a partner, have revealed an extremely distant and therefore very young galaxy that looks surprisingly like our Milky Way. The galaxy is so far away its light has taken more than 12 billion years to reach us: we see it as it was when the Universe was just 1.4 billion years old. It is also surprisingly unchaotic, contradicting theories that all galaxies in the early Universe were turbulent and unstable. This unexpected discovery challenges our understanding of how galaxies form, giving new insights into the past of our Universe. Credit: Rizzo et al./European Southern Observatory.

So the new galaxy, SPT0418-SE, adds to earlier evidence that the early universe was considerably less chaotic than we once thought. The new paper summarizes the issue with reference to the unexpectedly strong emission lines found in the data:

This spectroscopic study of a z > 4 galaxy opens up many questions, including the spatial arrangement and stellar/gas/metallicity distribution of the companion; the merging hypothesis of SPT0418-47; the dark-matter halo of the system; the overdensity of this potentially crowded field; reconciling the relatively high chemical abundances with the short formation time and the moderate stellar mass for the whole system; and interpreting the small [N ii] 122 and 205 ?m luminosities in the context of either a soft radiation field and/or a high N/O.

But again that note of high-redshift caution that I mentioned last week:

We attempt to reconcile the high metallicity in this system by invoking early onset of star formation with continuous high star-forming efficiency or by suggesting that optical strong line diagnostics need revision at high redshift. We suggest that SPT0418-47 resides in a massive dark-matter halo with yet-to-be-discovered neighbors.

Clearly scientists will be looking hard at how high-redshift targets are interpreted even as they continue to hypothesize about astrophysical mechanisms and star formation efficiency to explain seemingly mature objects at this early era. The game is afoot, as Sherlock Holmes used to say, and we’re a long way from reaching firm conclusions. The data are going to start coming fast and furious as we keep mining JWST and using ALMA to examine the universe in this early stage, as witness the image below, which I found just this morning. It shows us another remarkable object.

Image: The radio telescope array ALMA has pin-pointed the exact cosmic age of a distant JWST-identified galaxy, GHZ2/GLASS-z12, at 367 million years after the Big Bang. ALMA’s deep spectroscopic observations revealed a spectral emission line associated with ionized Oxygen near the galaxy, which has been shifted in its observed frequency due to the expansion of the Universe since the line was emitted. This observation confirms that the JWST is able to look out to record distances, and heralds a leap in our ability to understand the formation of the earliest galaxies in the Universe. Credit: NASA / ESA / CSA / T. Treu, UCLA / NAOJ / T. Bakx, Nagoya U.

The paper is Bo Peng et al., “Discovery of a Dusty, Chemically Mature Companion to a z ? 4 Starburst Galaxy in JWST ERS Data,” The Astrophysical Journal Letters 944 No. 2 L36 (17 February 2023). Full text. The paper on SPT0418-47 is Rizzo et al., “A dynamically cold disk galaxy in the early Universe,” Nature 584 (12 August 2020), pp. 201–204. Abstract. The GHZ2/GLASS-z12 paper is Bakx et al., “Deep ALMA redshift search of a z 12 GLASS-JWST galaxy candidate,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Volume 519, Issue (4 March 2023), pp. 5076–5085 (abstract).