Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Musings on Art, Brown Dwarfs & Galactic Disks

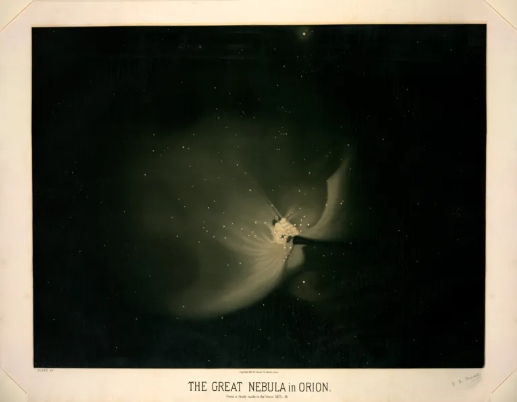

I was getting ready to start writing a story with implications for brown dwarfs and the galaxy’s ‘thick disk’ (as opposed to its ‘thin disk,’ about which more in a moment) when I ran across the artwork below. This is the work of French artist and astronomer Étienne Léopold Trouvelot (1827-1895), whose careful astronomical observations were rendered into illustrations and pastel drawings in the era before astrophotography. I learned from Maria Popova’s The Marginalian that Trouvelot produced 50 scientific papers, but almost 7000 works of art based on what he saw. Thus the study of part of the Milky Way below, evidently created somewhere between 1874 and 1876.

Trouvelot’s work caught the attention of the director of the Harvard Observatory, who invited him to join its staff in 1872. The concept of his art was to get across to those without the privilege of seeing these objects through a telescope just how they looked to a trained scientist. He przed the value of human rendering over instrumentation, as in this passage from the introduction to The Trouvelot Astronomical Drawings Manual, published in 1882:

Although photography renders valuable assistance to the astronomer in the case of the Sun and Moon … for other subjects, its products are in general so blurred and indistinct that no details of any great value can be secured. A well-trained eye alone is capable of seizing the delicate details of structure and of configuration of the heavenly bodies, which are liable to be affected, and even rendered invisible, by the slightest changes in our atmosphere.

Thus the view from the 1870s. These days we explore the deep sky without the flourishes of a human pen through exquisite imagery from our Earth-based telescopes and space instruments like Hubble and JWST. But I always like to learn more about the development of our views of the cosmos, and wanted to introduce Centauri Dreams readers to a figure I only learned about over the weekend. I notice that Maria Popova is producing high-quality prints of some of Trouvelot’s work, with the proceeds benefiting an attempt to build a public observatory in New York City. A worthy project; I’m sure Trouvelot would have approved.

Brown Dwarfs and the Thick Disk

JWST’s early imaging has already proven stunning, and the discoveries mount. Today we look at a small object called GLASS-JWST-BD1, a member of that subclass of brown dwarfs known as T dwarfs. These are difficult objects to detect, with temperatures between 500 and 1500 K, and thus useful for exploring the boundary between star and planet when we can find them. What is exciting here is the demonstration of what JWST can do as we push outward in our observations of stars that cannot ignite hydrogen fusion, looking now into more distant parts of the galactic disk.

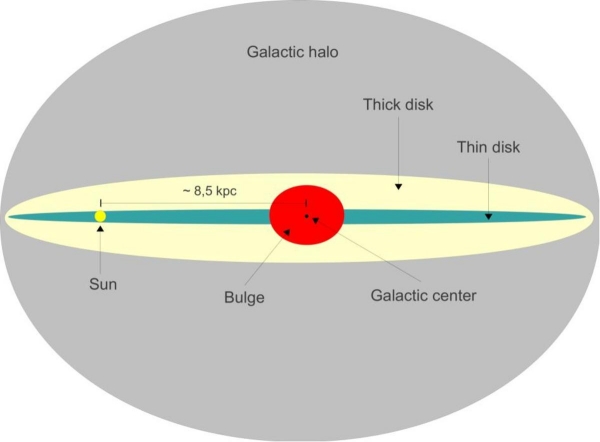

Objects like this emit primarily at infrared wavelengths. Their inherent faintness has meant that when we do surveys of brown dwarfs, we are working largely with brown dwarfs within 100 parsecs (326 light years) or less of the Sun. That has made it difficult to find such objects in the galaxy’s ‘thick disk,’ which consists of largely metal-poor stars rising well above the galactic plane. Surveys using the Hubble telescope’s WFC3 instrument have pushed detection further out but JWST’s results change the game.

Image: Edge on diagram of the Milky Way with several structures indicated (not to scale). The thick disk is shown in light yellow. Credit: Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Indeed, the discovery paper puts the matter this way with reference to Hubble:

…these surveys are restricted to wavelengths < 2 ?m, limiting their sensitivity to the reddest and coldest brown dwarfs. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) represents a major step forward in the detection of cool and distant brown dwarfs, with imaging and spectroscopy extending to ? 5?m and providing orders of magnitude greater sensitivity than Spitzer.

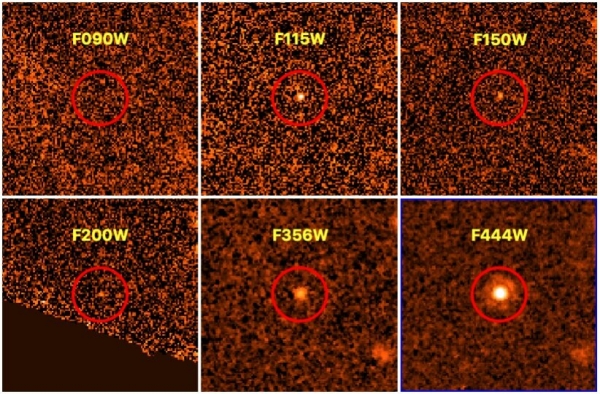

Image: Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), an international team of astronomers have detected a new faint, distant, and cold brown dwarf. The newly found object, designated GLASS-JWST-BD1, turns out to be about 31 times more massive than Jupiter. Credit: Nonino et al., 2022.

The work was led by Mario Nonino of the Astronomical Observatory of Trieste in Italy. GLASS-JWST-BD1 is between 1850 and 2350 light years from the Sun in a direction perpendicular to the galactic plane. Its mass is calculated at 31.43 Jupiter masses, with an effective temperature of 600 K. Its age is estimated at 5 billion years.

The discovery was made with JWST’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSPEC) and Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS). We only have about 400 known T dwarfs to date, but it’s clear that JWST will expand the catalog substantially. What we’re seeing here is that JWST is able to probe out into the galactic thick disk to find objects that are small and faint, meaning that the study of brown dwarfs, their metallicity and the evolution of their atmospheres, will be considerably enhanced.

Backyard Brown Dwarfs

From an entirely different dataset comes brown dwarf news from the citizen science project Backyard Worlds: Planet 9, which has just announced the discovery of 34 binary star systems where a brown dwarf is a companion object to a white dwarf. Citizen scientist Frank Kiwy is in fact listed as lead author of the paper on these discoveries that appears in The Astronomical Journal. Kiwy’s work involved data mining within a database of 4 billion objects in in the NOIRLab Source Catalog DR2.

We have a long way to go in learning how common brown dwarf companions to stars are, but these are objects that merit attention for what they can tell us about atmospheres both stellar and planetary. Brown dwarf atmospheres contain interesting molecules and offer hints to the development of planetary atmospheres in gas giants.

Moreover, have you looked at the numbers of some of these citizen scientist projects lately? Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 has a network encompassing over 100,000 volunteers who scan telescope images to search for features that machine learning algorithms may miss. The binary systems Kiwy found were among a far larger group of 2500 potential ultracool brown dwarfs that appear in the NOIRLab data. So while JWST pushes the limits from L2, data gathering from more than 40 Earth-based instruments collected in the NOIRLab holdings is being combed by citizen volunteers.

Aaron Meisner is an astronomer at NOIRLab (National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory) and the co-founder of Backyard Worlds:

“These discoveries were made by an amateur astronomer who conquered astronomical big data. Modern astronomy archives contain an immense treasure trove of data and often harbor major discoveries just waiting to be noticed.”

Something tells me that Étienne Trouvelot would have liked the idea of an amateur making contributions worthy of professional publication. In any case, wouldn’t he have loved to have gotten hold of some of the views we’re seeing from JWST? It’s hard, though, to see how he could have crafted works of art more lovely than the Webb instrument’s recent deep field images. “[No] human skill,” he once admitted, “can reproduce upon paper the majestic beauty and radiance of the celestial objects.”

Nonetheless, his work is deeply attractive. Let me close with another, this one of the Orion Nebula.

The paper is Nonino et al, “Early results from GLASS-JWST. XIII. A faint, distant, and cold brown dwarf,” submitted to Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint). The Kiwy paper is “Discovery of 34 Low-mass Comoving Systems Using NOIRLab Source Catalog DR2,” Astronomical Journal Vol. 164, No. 1 (6 June 2022). Abstract.

CNEOS 2014-01-08: Sampling the Interstellar Meteor

How unusual that the study of an interstellar object should receive a boost from the United States Space Command, which is responsible for US military operations off-planet. But that’s part of the story of CNEOS 2014-01-08, which is described in its discovery paper as “a meteor of interstellar origin.” The 2019 finding came from Harvard’s Avi Loeb, working with then undergraduate student Amir Siraj. Loeb had been examining a catalog containing data on meteors over the last three decades in terms of the strength of their fireball, prompted by a 2018 fireball off the Kamchatka peninsula.

The Kamchatka meteor produced a blast with ten times the energy of the Hiroshima bomb, leading Loeb to put Siraj to work on calculating the past trajectories of the fastest meteors in the CNEOS catalog – CNEOS is NASA’s Center for Near Earth Object Studies. In an email yesterday morning, Loeb explained that numerous factors went into the study. Siraj was able to work with the position and velocity of the meteors at impact while factoring in the Earth’s gravity as well as that of the Sun and planets.

You would think that the fastest such objects would be those with interstellar implications, but it turns out that the fastest meteor in the catalog was not on a hyperbolic orbit, but had made a head-on collision with the Earth. But CNEOS 2014-01-08, which struck the Earth in 2014, impacting the ocean near the coast of Papua New Guinea, was another matter. The 2019 discovery paper (citation below) outlined the case for this object as interstellar in origin, unbound to the Sun.

A new paper is now available, submitted to the Journal of Astronomical Instrumentation. Says Loeb:

In our 2019 discovery paper, Amir and I inferred CNEOS-2014–01–08 to be moving at nearly sixty kilometers per second outside the Solar system, twice faster than the characteristic speed of stars in the so-called “Local Standard of Rest” of the Milky Way. In our new paper we took account of the meteor slowdown in the atmosphere and found that its speed was initially larger than the value measured from the fireball deep in the atmosphere by twenty kilometers per second. If the meteor was natural in origin, then this high initial speed suggests gravitational ejection from a deep potential well, such as found in the interior of a planetary system, within the orbit of a Mercury-like planet around a Sun-like star. Alternatively, the meteor could have been a technological object propelled by artificial means.

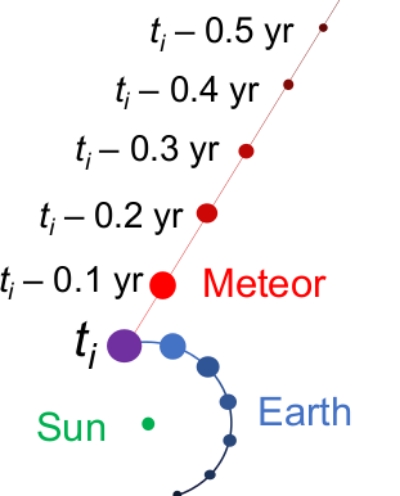

Image: This is Figure 1 from the paper. Caption: Trajectory of the January 8, 2014 meteor (red), shown intersecting with that of Earth (blue) at the time of impact, ti = 2014-01-08 17:05:34. Credit: Siraj & Loeb.

We’re able to draw some conclusions about this interstellar meteor even from the relatively sparse data available. But first, a word about the data collection process. You can imagine how wide-ranging the network of sensors that tracks objects entering the Earth’s atmosphere for reasons of national security must be. I learned from Loeb’s email that Space Command and NASA had made an agreement in 2020 that would boost NASA’s asteroid tracking capabilities through the use of Pentagon resources. Thus NASA is able to take advantage of light curve data generated by this source.

For more on these interactions, see Amir Siraj’s Spy Satellites Confirmed Our Discovery of the First Meteor from Beyond the Solar System. Because confirming the nature of CNEOS-2014–01–08 required referencing classified datasets, a letter to NASA from US Space Command came into play, issued on April 6, 2022 and making note of the 2019 paper by Loeb and Siraj. The letter confirms the interstellar nature of this object.

Loeb points out that as the meteor detection occurred in January of 2014, it predates the discovery of ‘Oumuamua by almost four years. Thus CNEOS-2014–01–08 “should be recognized as the first massive interstellar object ever discovered.”

6/ “I had the pleasure of signing a memo with @ussfspoc’s Chief Scientist, Dr. Mozer, to confirm that a previously-detected interstellar object was indeed an interstellar object, a confirmation that assisted the broader astronomical community.” pic.twitter.com/PGlIOnCSrW

— U.S. Space Command (@US_SpaceCom) April 7, 2022

We can already make some statements, as the authors do in the new paper, about the composition of this object, because the US Department of Defense released, along with its confirmation letter, the light curve for CNEOS 2014-01-08, showing three flashes separated from each other by roughly a tenth of a second. The authors note that it is possible to use the measured direction of motion for the object to calculate the altitude of these flashes as well as the density of the air at the level they occurred.

The calculations are complex and I send you to the paper for the details. But here is a taste of the logic behind them as stated within:

When a supersonic meteor moves through air, it is subject to a friction force on its frontal surface area. The force per unit area equals the ambient mass-density of air times the square of the object’s speed. This ram pressure reflects the flux of momentum per unit area per unit time delivered to the object in slowing down its motion. The meteor disintegrates if the ram pressure exceeds the yield strength of the material it is made of, representing the maximum stress that can be applied to it before it begins to deform. The heat released by the friction with air melts the fragments and generates the flashes of light in the fireball.

Loeb and Siraj calculated the ram pressure exerted on CNEOS 2014-01-08 at the time the three flashes in the light curve occurred. Here I’ll again draw from Loeb’s email:

We translated the meteor light curve to a plot of the power released as a function of the ambient ram pressure. To our surprise, the disintegration of CNEOS-2014–01–08 occurred when the external ram pressure reached a value of 113 megapascals (MPa). This value is twenty times larger than the highest yield strength of stony meteorites and two times larger than that of the toughest iron meteorites. The first interstellar meteor could not have been a stony meteorite similar to most solar system asteroids.

Indeed, as Loeb points out, the required material strength for this object has to exceed that of iron meteorites to allow it to survive the ram pressure down to the 18.7 kilometer altitude where the brightest flare shows up in the data. About one in twenty of the objects impacting the Earth are iron meteorites – 90% to 95% iron, mixing with a remainder of nickel alloys and trace amounts of iridium, gallium and sometimes gold. Loeb’s email points out how useful a sample of this object would be:

We could confirm the interstellar origin of this meteor independent of its speed based on its composition being different from solar system objects. It could deliver exotic abundances of heavy elements, depending on the proximity of its birth place to a supernova or a merger event of two neutron stars.

Confirming this with actual samples from the object would be ideal, which is why Loeb is hoping to find the funding to put what he describes as “an experienced expedition team” and the needed equipment to reach the impact site off the coast of Papua New Guinea. He has already received half a million dollars toward this purpose but needs another million to proceed with the expedition. From the paper:

The best way to decipher anomalies is to gather additional data. We are currently planning an expedition to Papua New Guinea where we could retrieve the meteor’s fragments from the ocean floor. Studying these fragments in a laboratory would allow us to determine the isotope abundances in CNEOS-2014-01-08 and check whether they are different from those found in solar system meteors. Altogether, anomalous properties of interstellar objects like CNEOS-2014-01-08 and ‘Oumuamua, hold the potential for revising conventional wisdom on our cosmic neighborhood. The expedition to the ocean floor around Papua New Guinea will illustrate metaphorically how scientific evidence expands our island of knowledge into the ocean of ignorance that surrounds it.

The search area appears to be a relatively reasonable 10 kilometers by 10 kilometers, offering the potential for discovery of fragments on the ocean floor. The plan is ambitious but seems entirely workable. I’ll close with its description in the paper:

Our plan is to mobilize a ship with a magnetic sled deployed using a long line winch. We will be operating approximately ? 300 km north of Manus Island. The team will consist of seven sled operators, plus the scientific team… We will tow a sled mounted with magnets, cameras and lights on the ocean floor inside of a 10 km × 10 km search box. A number of sources have been used to narrow the search site to this relatively small search box. A sled, ? 2 m long, ? 1 m wide and ? 0.2 m centimeters tall weighing about ? 55 kg, will be towed along the seabed to sample for ferro-magnetic meteorite fragments from the CNEOS 2014-01-08.

It would never have occurred to me when I began publishing Centauri Dreams that one day we might be mounting a search in our own oceans looking for debris from an interstellar object. Readers with deep pockets take note.

The paper is Siraj & Loeb, “An Ocean Expedition by the Galileo Project to Retrieve Fragments of the First Large Interstellar Meteor CNEOS 2014-01-08,” submitted to the Journal of Astronomical Instrumentation (preprint). The discovery paper is Siraj & Loeb, “The 2019 Discovery of a Meteor of Interstellar Origin,” submitted to Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint).

Ross 508 b: What We Can Learn from a Red Dwarf Super-Earth

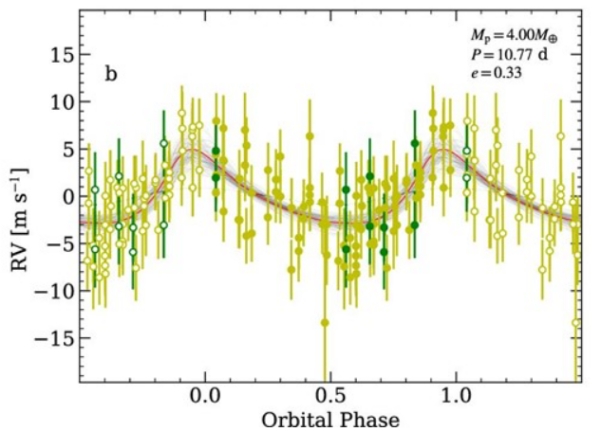

The discovery of a super-Earth around the M-dwarf Ross 508 gives us an interesting new world close to, if not sometimes within, the inner edge of the star’s habitable zone. This is noteworthy not simply because of the inherent interest of the planet, but because the method used to detect it was Doppler spectroscopy. In other words, radial velocity methods in which we study shifts in the spectrum of the star are here being applied to a late M-dwarf that emits most of its energies in the near-infrared (NIR).

I usually think about transits in relation to M-dwarf planets, because our space-based observatories, from CoRoT to Kepler and now TESS, have demonstrated the power of these techniques in finding exoplanets. M-dwarfs are made to order for transits because they’re small enough to offer deep transits – the signature of the planet in the star’s lightcurve is more pronounced than a transit across a larger star.

From a radial velocity perspective, planets in an M-dwarf habitable zone orbit the star closely, making for a strong RV signal if we can detect it. But there are limitations to both methods: Transit searches have clustered around younger red dwarfs that are relatively more massive. In terms of radial velocity, most exoplanet surveys have employed optical CCDs, whereas older, more evolved M-dwarfs are brighter in the near-infrared (NIR). From an exoplanet perspective, then, it can be said that cool late M-dwarfs remain largely unexplored terrain, a situation that is now being addressed.

What is needed for this kind of work is a spectrograph specifically designed for NIR wavelengths, and in fact NIR spectrographs have begun to appear, some of which involve projects we’ve looked at here, as for example CARMENES (Calar Alto high-Resolution search for M dwarfs with Exoearths with Near-infrared and optical Echelle Spectrographs). Other such projects, like SPIROU (SPectropolarimetre InfraROUge) and HPF (Habitable Planet Finder) also employ NIR spectrographs.

The most famous of the M-dwarf planets is, of course, Proxima Centauri b, found by the team led by Guillem Anglada-Escudé using visible light spectroscopy, but M-dwarfs with temperatures below the roughly 3000 K of Proxima Centauri, which are considered late-type M-dwarfs, have not been systematically searched for planets.

Consider this: Seen from 30 light years out, the Sun is a 5th magnitude object in visible light, but a 3rd magnitude target in infrared. A late-type red dwarf comes in at around 19th magnitude in visible light, but brightens to 11th magnitude in the infrared. We’ve found dozens of exoplanets around stars with effective temperature higher than 3,000 K, but only a handful around cooler M-dwarfs. The authors of the discovery paper on Ross 508 b are not exaggerating when they describe the detection of planets around such stars using high-precision radial velocity methods as “a frontier in exoplanet exploration.” Their paper serves as a helpful introduction to NIR spectroscopy.

The team, led by Hiroki Harakawa (NAOJ Subaru Telescope, Hawaii), reports on the Ross 508 work as the beginning of a campaign exploring low-temperature stars with the Subaru Telescope IRD (InfraRed Doppler) instrument, which the Astrobiology Center of Japan, where it was developed, describes as the first high-precision infrared spectrograph for 8-meter class telescopes. The observing program now underway is the IRD Subaru Strategic Program (IRD-SSP), which began in 2019 and scans late-type M-dwarfs. Stable red dwarfs with low surface activity are the targets.

Radial velocity is the detection of stellar wobbles that can be indicated in several ways, making finding planets a matter of excluding false-positives as much as locating candidates. Because M-dwarfs are prone to violent flare activity, they’re problematic thanks to the changes in surface brightness they produce. A false planetary signature like this has to be extracted and then subtracted from the signature of a possible planet. Ross 508 b holds up to the scrutiny, indicating a minimum mass about four times that of Earth at an average distance of 0.05 AU from the star.

There are indications that the planet’s orbit is elliptical, with an orbital period of about 11 days, part of which may include crossing into and back out of the habitable zone. An interesting consequence of studying late-type M-dwarfs is that their presumed lower levels of flare activity may offer a planetary environment more conducive for life than their younger cousins, with a surface less frequently bathed in flare-induced radiation. I hasten to add that this is a tentative conclusion still the subject of active study.

In any case, a planet like Ross 508 b may well turn out to be a target for atmospheric analysis once we’re able to image it directly, probably with the coming generation of 30-meter class telescopes. Transits are unlikely here, so we’re reliant on imaging rather than transmission spectroscopy, which analyzes planetary atmospheres by studying the star’s light as it filters through the atmosphere during transit events.

We should be hearing a lot more from the IRD-SSP project. Lead author Hiroki Harakawa has this to say:

“Ross 508 b is the first successful detection of a super-Earth using only near-infrared spectroscopy. Prior to this, in the detection of low-mass planets such as super-Earths, near-infrared observations alone were not accurate enough, and verification by high-precision line-of-sight velocity measurements in visible light was necessary. This study shows that IRD-SSP alone is capable of detecting planets, and clearly demonstrates the advantage of IRD-SSP in its ability to search with a high precision even for late-type red dwarfs that are too faint to be observed with visible light.”

Image: Periodic variation in the line-of-sight velocity of the star Ross 508 observed by IRD. It is wrapped around the orbital period of the planet Ross 508 b (10.77 days). The change in the line-of-sight velocity of Ross 508 is less than 4 meters per second, indicating that IRD captured a very small wobble that is slower than a person running. The red curve is the best fit to the observations and its deviation from a sinusoidal curve indicates that the planet’s orbit is most likely elliptical. Credit: Harakawa et al. 2022.

The authors are interested in the question of eccentricity, pointing out that it may offer early clues to the planet’s origin, although it will take further radial velocity measurements to clarify just how eccentric this orbit is. The paper examines four different scenarios to explain the RV data, but none of these constrain the eccentricity conclusively. From the paper:

…there remains the possibility that Ross?508?b is in a high-eccentricity orbit. In a multiple-planet system, migrated planets experience giant impacts or are trapped in a resonant chain (e.g., Ogihara & Ida 2009; Izidoro et al. 2017). Planetary eccentricities are excited by giant impacts. The eccentricity of a planet can be also excited by gravitational interactions between neighboring planets or secular perturbations from a (sub)stellar companion on a wider orbit. The confirmation of a long-term RV trend will help disentangle the formation history of the super-Earth Ross?508?b.

It’s also far too early to make any statements about this planet’s habitability. For one thing, the inner edge of the habitable zone at Ross 508 is not well understood, depending as it does on the star’s luminosity, which in turn is affected by its low metallicity. It does appear that the planet is near the runaway greenhouse limit. But our knowledge of super-Earth habitability is nascent. Climate, plate tectonics, and other potent factors would play a role that we won’t be able to measure until we can start taking atmospheric measurements with next generation telescopes.

Ross 508 b is one of the faintest, lowest-mass stars with a planet detected through radial velocity. Its discovery points to the need for a large telescope and a high precision spectrograph in the near infrared to analyze the planetary systems around this kind of star. We should be learning a great deal more about late M-dwarfs as we press on with projects like the IRD Subaru Strategic Program, coupling near infrared RV work with transit observations from space and ground-based observatories.

The paper is Harakawa et al., “A Super-Earth Orbiting Near the Inner Edge of the Habitable Zone around the M4.5-dwarf Ross 508,” Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan 30 June 2022 (full text).

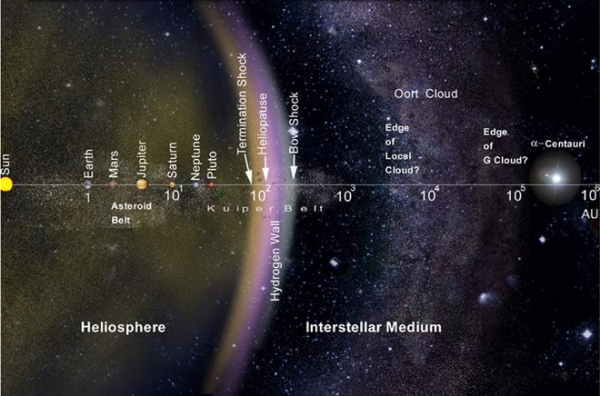

Interstellar Deceleration: Can We Ride the ‘Bow Shock’?

Interesting things happen at the edge of the Solar System. Or perhaps I should say, at the boundary of the heliosphere, since the Solar System itself conceivably extends (in terms of possible planets) further out than the 100 or so AU that marks the heliosphere’s boundary at its closest. The fact that the heliosphere is pliable and reacts among other things to the solar cycle in turns means that the boundary is a moving target. It would be useful if we could get something like JHU/APL’s Interstellar Probe mission out well beyond the heliosphere to help us understand this morphology better.

But let’s think about the heliosphere’s boundaries from the standpoint of incoming spacecraft. Because deceleration at the destination system is a huge problem for starship mission planning. A future crew, human or robotic, could deploy a solar sail to slow down, but a magsail seems better, as its effects kick in earlier on the approach. Looking at the image below, however, suggests another possibility, one using the interactions between stars and the interstellar medium to assist the slowdown. And then the question arises: Does our own Sun produce a similar kind of bow shock?

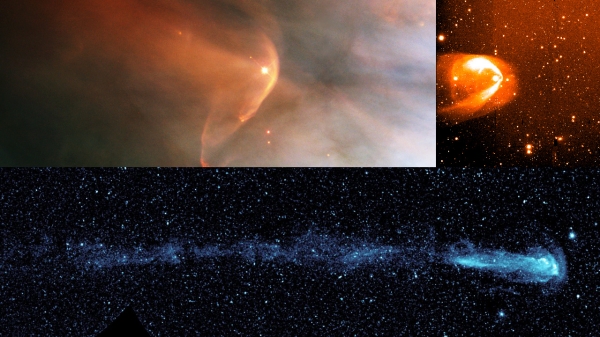

Image: A multi-wavelength view of Zeta Ophiuchi. Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Dublin Inst. Advanced Studies/S. Green et al.; Infrared: NASA/JPL/Spitzer.

Here we’re looking at a star, Zeta Ophiuchi, that is some 440 light years from Earth. It’s about 20 times as massive as the Sun, and evidently was once in a tight orbit around another star that became a supernova perhaps a million years ago. As a result, Zeta Ophiuchi was ejected from its binary orbit, and we have data from the Spitzer Space Telescope as well as the Chandra X-ray Observatory depicting the spectacular after-effects. The shock wave consists of matter blowing away from the star’s surface, slamming into gas. In the above image, the shock wave is in vivid red and green.

The latest work on Zeta Ophiuchi comes from a team led by Samuel Green (Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Ireland), with a paper laying out computer modeling of the shock wave and running the data against observational data obtained at X-ray, optical, infrared and radio wavelengths. Their results are interesting, as what can be found in data on the X-ray emissions shows that it is brighter than the modeling suggests. The bubble of X-ray emissions shows up in blue around the star in the image above. Its brightness indicates further modeling including turbulence and particle acceleration is needed.

I’ll send you to the paper for more on Zeta Ophiuchi, whose position – enveloped by the nebula Sh2-27 and pushing through dense dust clouds – makes it a natural for studying what happens when a shock wave develops. But let’s cut back to more mundane interactions, such as what happens when the Sun’s solar wind encounters the interstellar medium. Does a bow shock form here? Depending on the relative velocity of the heliosphere and the strength of the local interstellar magnetic field, such a phenomenon may or may not occur, as suggested by Voyager data as well as earlier findings from the Interstellar Boundary Explorer spacecraft (IBEX). A bow shock had been assumed, but we’re learning that these interactions are complicated.

While we investigate our heliosphere’s interactions with the interstellar medium, we can point to numerous bow shocks especially associated with more massive stars. In fact, a citizen science effort called The Milky Way Project is all about mapping bow shocks, building our catalog of these interesting astrophysical features. Learning more about how bow shocks form will clearly take us into the influence of interstellar magnetic fields as they roil the outflowing stellar winds they encounter. The density and pressures of the medium and the speed of the star’s astrosphere determine the result.

Image: Stars travel through the galaxy surrounded by a bubble of charged gas and magnetic fields, rounded at the front and trailing into a long tail behind. The bubble is called an astrosphere, or — in the case of the one around our Sun — a heliosphere. This image shows a few examples of astrospheres that are very strong and therefore visible.

Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center.

All of this has implications for our thinking about certain kinds of interstellar missions. If a star does form a bumper of plasma and higher density gas at the edge of its astrosphere, then as Gregory Benford has suggested (in correspondence some years back), we are looking at an obvious place to slow down an incoming starship. As Benford noted, the bow shock produces 3D structures, surfaces within which one can move while shedding speed, perhaps braking via a magsail. Each star would produce its own unique deceleration environment, allowing us to brake where possible along the bow shock, the astropause (cognate to the heliopause) and the termination shock.

We are talking about long, spiraling approaches to a destination system with continual magsail braking – decelerating from interstellar velocities is not going to be fast or easy. But it seems clear that one kind of precursor mission before we send missions that are more than flybys to other stars will be to visit our own shock environment at the edge of the Solar System, where we can learn more about using shock surfaces to slow down. I like the way Benford put it in an email: “As a starship approaches a star, sensing the shock structures will be like having a good eye for the tides, currents and reefs of a harbor.” For more, see 2012’s Starship Surfing: Ride the Bow Shock, where I assumed the existence of a solar bow shock.

All of this reminds us that the interstellar medium is anything but uniform. If the Sun is currently near the boundary of the Local Interstellar Cloud (and its exact position within it is unclear), the Alpha Centauri stars appear to be outside that cloud in the direction of the G cloud, another variation in the medium. So we have another kind of boundary crossing to consider. Different hydrogen densities play havoc with the Bussard ramjet concept, too. Robert Bussard assumed hydrogen densities in the range of 1 hydrogen atom per cubic centimeter, but move outside denser clouds and that figure should drop precipitously. If you’re flying an interstellar ramjet, pay attention to the clouds!

The Zeta Ophiuchi paper is Green et al., “Thermal emission from bow shocks. II. 3D magnetohydrodynamic models of zeta Ophiuchi,” in process at Astronomy & Astrophysics (abstract).

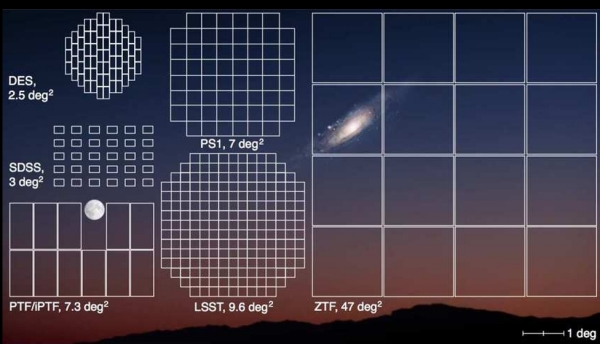

The Challenge of ‘Twilight Asteroids’

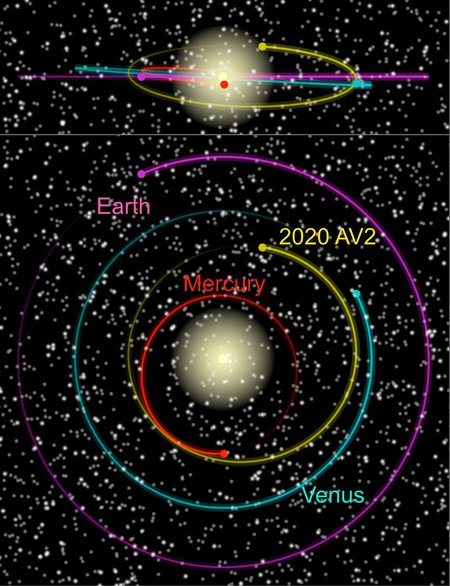

We have the Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar Observatory to thank for the detection of the strikingly named ‘Ayló’chaxnim (2020 AV2). This is a large near-Earth asteroid with a claim to distinction, being the first NEO found to orbit inside the orbit of Venus. I love to explore the naming of things, and now that we have ‘Ayló’chaxnim (2020 AV2), we have to name the category, at least provisionally. The chosen name is Vatira, which in turn is a nod to Atira, a class of asteroids that orbit entirely inside Earth’s orbit. Thus Vatira refers to an Atira NEO with orbit interior to Venus.

As to the ‘Ayló’chaxnim, it’s a word from indigenous peoples whose ancestral lands took in the mountainous region where the Palomar Observatory is located. I’m told by the good people at Caltech that the word means something like ‘Venus Girl.’ On June 7, people of Pauma descent gathered for a ceremony at the observatory, having been asked by the team manning the Zwicky Transient Facility to choose a local name.

I couldn’t tell you how ‘Ayló’chaxnim is pronounced, but with the ZTF on watch, it’s possible we’ll find more Vatiras, or at least Atiras, which seem to be more numerous, so we may have more Pauma names to come and perhaps we’ll learn. 2020 AV2 is 1 to 3 kilometers in size and has an orbit tilted about 15 degrees from the plane of the Solar System. On its 151 day orbit, it stays interior to Venus and comes close to the orbit of Mercury. Postdoc Bryce Bolan at Caltech flagged it as a candidate in early 2020.

The ZTF itself is a survey camera mounted on the Samuel Oschin Telescope at Palomar, conducting a wide-field survey making rapid scans of the sky. 2020 AV2, says Caltech’s George Helou, who is a ZTF co-investigator, is on an interesting orbit, surely the result of migration from further out in the system:

“Getting past the orbit of Venus must have been challenging. The only way it will ever get out of its orbit is if it gets flung out via a gravitational encounter with Mercury or Venus, but more likely it will end up crashing on one of those two planets.”

Image: The Zwicky Transient Facility field of view. The ZTF Observing System delivers efficient, high-cadence, wide-field-of-view, multi-band optical imagery for time-domain astrophysics analysis. The camera utilizes the entire focal plane of 47 square degree of the 48-inch Samuel Oschin Schmidt telescope, providing the largest instantaneous field-of-view of any camera on a telescope of aperture greater than 0.5 m: each image will cover 235 times the area of the full moon. Credit: Zwicky Transient Facility.

This close to the Sun, Vatiras are only going to be visible at dusk or dawn. As the University of Hawaii’s Scott Sheppard points out in a recent issue of Science, our asteroid surveys mostly take place with a dark night sky, which implies that small objects orbiting between the Earth and the Sun are not likely to be found. Modeling of the NEO population predicts that objects as large as 2020 AV2 are unlikely among Vatiras but smaller objects could be plentiful. Asteroid surveys interior to Venus’ orbit are few, so there is work here for facilities like the ZTF, or the NSF’s Blanco 4-meter telescope in Chile with the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) to fill out this population. Both have fields of view sufficient to carry out this kind of survey.

So let’s get down to the asteroid mitigation question. Sheppard points out that what with current NEO surveys coupled with formation models for these objects, more than 90 percent of what he calls ‘planet killer’ NEOs have probably already been found – these would be objects larger than 1 kilometer, and he’s talking here about the entire range of NEOs, not just those interior to the orbits of Earth or Venus. He writes:

The last few unknown 1-km NEOs likely have orbits close to the Sun or high inclinations, which keep them away from the fields of the main NEO surveys. The 48-inch Zwicky Transient Facility telescope has found one Vatira and several Atira asteroids, making it one of the most prolific asteroid hunters interior to Earth. To combat twilight to find smaller asteroids, one can use a bigger telescope. Large telescopes usually do not have big fields of view to efficiently survey. The National Science Foundation’s Blanco 4-meter telescope in Chile with the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) is an exception. A new search for asteroids hidden in plain twilight with DECam has found a few Atira asteroids, including 2021 PH27.

Sheppard’s also describes a category he calls ‘city killers,’ which takes in NEOs larger than 140 meters; of these, he believes we have found about half. The progress in tracking NEOs has been heartening as we learn about potentially dangerous trajectories, and turning to twilight surveys like these will help us learn more about NEOs hidden in the glare of the Sun.

It turns out that the Zwicky team recently found the asteroid with the smallest known semimajor axis (0.46 AU). This is 2021 PH27, an object with high eccentricity whose orbit crosses the orbit of Mercury as well as Venus. Thus, given our categorization, PH27 is an Atira rather than a Vatira. With a perihelion of 0.13 AU, this NEO shows 1 arc minute of precession per century, the highest of any object in the Solar System including Mercury. This is another large NEO at about 1 kilometer in size. Although as Sheppard notes:

…because the diameter of these interior asteroids is calculated with an assumed albedo and solar phase function, the actual diameters for both of these discoveries could be under 1 km. This would put them in a more-expected population and make them less of a statistical fluke.

Image: 2020 AV2 orbits entirely within the orbit of Venus. Credit: Bryce Bolin/Caltech

Clearly we have much to do to build our catalog of objects close to the Sun. We can extend the catalog of exotic names as well. Asteroids called Amors are those that approach the Earth but do not cross its orbit. Apollos do cross the orbit of the Earth but have semimajor axes greater than Earth’s. Atens, in turn, cross Earth’s orbit but have semimajor axes less than that of the Earth. Sheppard points out that NEOs have dynamically unstable orbits, and speculates that a reservoir that replenishes their numbers must exist because the overall count seems to be in a steady state.

Among possible reservoirs are those that may exist in long-term resonances with Venus or Mercury, and there may conceivably be a population of asteroids not yet observed, the so-called Vulcanoids, that could have orbits entirely within the orbit of Mercury. Sheppard’s excellent article makes the point that Vulcanoids would be at the mercy of many factors, including Yarkovsky drift, collisions and thermal fracturing from proximity to the sun, so they’re likely uncommon. We do know that spacecraft observations of the region near the Sun seem to rule out Vulcanoids larger than 5 kilometers, but stable reservoirs for smaller objects may exist. Remember, too, that we have found numerous exoplanets closer to their host stars than the Vulcanoid region in our Solar System.

Overall, NEOs in the Sun’s glare should not be too prolific:

Fewer Atiras should exist than the more-distant NEOs, and even fewer Vatiras, because it becomes harder and harder for an object to move inward past Earth’s and then Venus’ orbit. Random walks of a NEO’s orbit through planetary gravitational interactions can make an Aten into an Atira and/or Vatira orbit and vice versa. Atiras should make up some 1.2% and Vatiras only 0.3% of the total NEO population coming from the main belt of asteroids (4). 2020 AV2 itself will spend only a few million years in a Vatira orbit before crossing Venus’ orbit. Eventually, 2020 AV2 will either collide with or be tidally disrupted by one of the planets, disintegrate near the Sun, or be ejected from the inner Solar System.

Scott Sheppard’s article is “In the Glare of the Sun,” Vol. 377 Issue 6604 (21 July 2022), pp. 366-367 (full text). For more on the Zwicky Transient Facility, see Graham et al., “The Zwicky Transient Facility: Science Objectives,” Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific Vol. 131, No. 1001 (22 May 2019). Full text.

Getting There Quickly: The Nuclear Option

Adam Crowl has been appearing on Centauri Dreams for almost as long as the site has been in existence, a welcome addition given his polymathic interests and ability to cut to the heart of any issue. His long-term interest in interstellar propulsion has recently been piqued by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s work on a mission to the Sun’s gravitational lens region. JPL is homing in on multiple sailcraft with close solar passes to expedite the cruise time, leading Adam to run through the options to illustrate the issues involved in so dramatic a mission. Today he looks at the pros and cons of nuclear propulsion, asking whether it could be used to shorten the trip dramatically. Beamed sail and laser-powered ion drive possibilities are slated for future posts. With each of these, if we want to get out past 550 AU as quickly as possible, the devil is in the details. To keep up with Adam’s work, keep an eye on Crowlspace.

by Adam Crowl

The Solar Gravitational Lens amplifies signals from distant stars and galaxies immensely, thanks to the slight distortion of space-time caused by the Sun’s mass-energy. Basically the Sun becomes an immense spherical lens, amplifying incoming light by focussing it hundreds of Astronomical Units (AU) away. Depending on the light frequency, the Sun’s surrounding plasma in its Corona can cause interference, so the minimum distance varies. For optical frequencies it can be ~600 AU at a minimum and light is usefully focussed out to ~1,000 AU.

One AU is traveled in 1 Julian Year (365.25 days) at a speed of 4.74 km/s. Thus to travel 100 AU in 1 year needs a speed of 474 km/s, which is much faster than the 16.65 km/s that probes have been launched away from the Earth. If a Solar Sail propulsion system could be deployed close to the Sun and have a Lifting Factor (the ratio of Light-Pressure to Weight of Solar Sail vehicle) greater than 1, then such a mission could be launched easily. However, at present, we don’t have super-reflective gossamer light materials that could usefully lift a payload against solar gravity.

Carbon nanotube mesh has been studied in such a context, as has aerographite, but both are yet to be created in large enough areas to carry large payloads. The ratio of the push of sunlight, for a perfect reflector, to the gravity of the Sun means an areal mass density of 1.53 grams per square metre gives a Lifting Factor of 1. A Sail with such an LF will hover when pointing face on at the Sun. If a Solar Sail LF is less than 1, then it can be angled and used to speed up or slow down the Sail relative to its initial orbital vector, but the available trajectories are then slow spirals – not fast enough to reach the Gravity Lens in a useful time.

Image: A logarithmic look at where we’d like to go. Credit: NASA.

Absent super-light Solar Sails, what are the options? Modern day rockets can’t reach 474 km/s without some radical improvements. Multi-grid Ion Drives can achieve exhaust velocities of the right scale, but no power source yet available can supply the energy required. The reason why leads into the next couple of options so it’s worth exploring. For deep space missions the only working option for high-power is a nuclear fission reactor, since we’re yet to build a working nuclear fusion reactor.

When a rocket’s thrust is limited by the power supply’s mass, then there’s a minimum power & minimum travel time trajectory with a specific acceleration/deceleration profile – it accelerates 1/3 the time, then cruises at constant speed 1/3 the time, then brakes 1/3 the time. The minimum Specific Power (Power per kilogram) is:

P/M = (27/4)*S2*T-3

…where P/M is Power/Mass, S is displacement (distance traveled) and T is the total mission time to travel the displacement S. In units of AU and Years, the P/M becomes:

P/M = 4.8*S2*T-3 W/kg

However while the Average Speed is 474 km/s for a 6 year mission to 600 AU, the acceleration/deceleration must be accounted for. The Cruise Speed is thus 3/2 times higher, so the total Delta-Vee is 3 times the Average Speed. The optimal mass-ratio for the rocket is about 4.41, so the required Effective Exhaust Velocity is a bit over twice the Average Speed – in this case 958 km/s. As a result the energy efficiency is 0.323, meaning the required Specific Power for a rocket is:

P/M = 14.9*S2*T-3 W/kg

For a mission to 600 AU in 6 years a Specific Power of 24,850 W/kg is needed. But this is the ideal Jet-Power – the kinetic energy that actually goes into the forward thrust of the vehicle. Assuming the power source is 40% (40% drive and 10% payload) of the vehicle’s empty mass and the efficiency of the higher-powered multi-grid ion-drive is 80%, then the power source must produce 77,600 W/kg of power. Every power source produces waste heat. For a fission power supply, the waste heat can only be expelled by a radiator. Thermodynamic efficiency is defined as the difference in temperature between the heat-source (reactor) and the heat-sink (radiator), divided by the temperature of the heat source:

Thermal Efficiency = (Tsource – Tsink) / Tsource

For a reactor with a radiator in space, the mass of that radiator is (usually) minimised when the efficiency is 25 % – so to maximise the Power/Mass ratio the reactor has to be really HOT. The heat of the reactor is carried away into a heat exchanger and then travels through the radiator to dump the waste heat to space. To minimise mass and moving parts so called Heat-Pipes can be used, which are conductive channels of certain alloys.

Another option, which may prove highly effective given clever reactor designs, is to use high performance thermophotovoltaic (TPV) cells to convert high temperature thermal emissions directly into electrical power. High performance TPV’s have hit 40% efficiency at over 2,000 degrees C, which would also maximise the P/M ratio of the whole power system.

Pure Uranium-235, if perfectly fissioned (a Burn-Up Fraction of 1), releases 88 trillion joules (88 TJ) per kilogram. A jet-power of 24,850 W/kg sustained for 4 years is a total power output of 3.1 TJ/kg. Operating the Solar Lens Telescope payload won’t require such power levels, so we’ll assume it’s negligible fraction of the total output – a much lower power setting. So our fuel needs to be *at least* 3.6% Uranium-235. But there’s multipliers which increase the fraction required – not all the vehicle will be U-235.

First, the power-supply mass fraction and the ion-drive efficiency – a multiplier of 1/0.32. Therefore the fuel must be 11.1% U-235.

Second, there’s the thermodynamic efficiency. To minimise the radiator area (thus mass) required, it’s set at 25%. Therefore the U-235 is 45.6% of the power system mass. The Specific Power needed for the whole system is thus 310,625 W per kilogram.

The final limitation I haven’t mentioned until now – the thermophysical properties of Uranium itself. Typically Uranium is in the form of Uranium Dioxide, which is 88% uranium by mass. When heated every material goes up in temperature by absorbing (or producing internally) a certain amount of heat – the so called Heat Capacity. The total amount of heat stored in a given amount of material is called the Enthalpy, but what matters to extracting heat from a mass of fissioning Uranium is the difference in Enthalpy between a Higher and a Lower temperature.

Considering the whole of the reactor core and the radiator as a single unit, the Lower temperature will be the radiator temperature. The Higher will be the Core where it physically contacts the heat exchanger/radiator. Thanks to the Thermal efficiency relation we know that if the radiator is at 2,000 K, then the Core must be at least ~2,670 K. The Enthalpy difference is 339 kilojoules per kilogram of Uranium Oxide core. Extracting that heat difference every second maintains the temperature difference between the Source and the Sink to make Work (useful power) and that means a bare minimum of 91.6% of the specific mass of the whole power system must be very hot fissioning Uranium Dioxide core. Even if the Core is at melting point – about 3120 K – then the Enthalpy difference is 348 KJ/kg – 89.3% of the Power System is Core.

The trend is obvious. The power supply ends up being almost all fissioning Uranium, which is obviously absurd.

To conclude: A fission powered mission to 600 AU will take longer than 6 years. As the Power required is proportional to the inverse cube of the mission time, the total energy required is proportional to the inverse square of the mission time. So a mission time of 12 years means the fraction of U-235 burn-up comes down to a more achievable 22.9% of the power supply’s total mass. A reactor core is more than just fissioning metal oxide. Small reactors have been designed with fuel fractions of 10%, but this is without radiators. A 5% core mass puts the system in range of a 24 year mission time, but that’s approaching near term Solar Sail performance.