One question jumps out at me from the blog entries that Cassini team members have been posting on the probe’s dazzling close pass by Enceladus. It’s from deputy project scientist Linda Spilker, who says: “I am thinking about the two Voyager flybys of the Saturn system that took place over 25 years ago. How in the world did we miss the Enceladus plumes back then???” Indeed, but that’s the nature of exploration, to learn something new each time you revisit a place, especially one that’s fully 10 AU out. The process is addictive, and breathtaking.

Do be aware of the flyby blog, offering an inside view of one of the most interesting of Cassini’s encounters thus far (also be aware that the entries are oddly out of order, a problem apparently being fixed). With the data downlink now started (as of about 0201 UTC today) via the Deep Space Network’s Goldstone station, we can ponder the chutzpah of taking a spacecraft so close to the huge geysers erupting out of the south pole of Enceladus. Cassini came within 200 kilometers of the surface as it flew through the outer edge of the plumes, and closed to a mere fifty kilometers at closest approach.

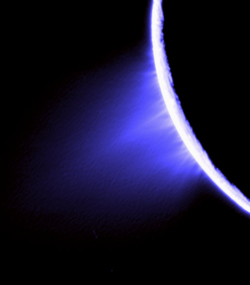

Image: Not from the latest flyby (images from that later), this false-color view of Enceladus has been enhanced to identify individual jets making up the plume. The images combined to create this view were acquired with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Nov. 27, 2005 at a distance of approximately 148,000 kilometers (92,000 miles) from Enceladus and at a sun-Enceladus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 161 degrees. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

Raw images are hitting the Web as I write (click the ‘Browse Latest 500 Raw Images’ arrow, but be patient; the server is apparently being slammed). And don’t miss this flyby video.

In terms of danger to the spacecraft, the threat is smaller than it at first appears, especially when you consider that Cassini deals with dust-size particles routinely as it orbits around Saturn. And the science return should be rich, with information on the density, size, composition and speed of the gas and particles collected. Sascha Kempf (Max Planck Institute, Heidelberg), deputy principal investigator for Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer, notes that various theories rise or fall on the outcome:

“There are two types of particles coming from Enceladus, one pure water-ice, the other water-ice mixed with other stuff. We think the clean water-ice particles are being bounced off the surface and the dirty water-ice particles are coming from inside the moon. This flyby will show us whether this concept is right or wrong.”

The halo of ice dust around Enceladus supplies Saturn’s E-ring with material from the apparently continuous eruptions. It’s known to be composed of water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, possibly ammonia and other trace gases, but Cassini will now find out whether the gases coming out of the plume are identical with those surrounding the moon. The result may give us insights into the processes driving the eruptions. With four more Enceladus flybys planned for this year, the success of this encounter may determine whether the next one is even closer.

They might have missed them, but they were strongly suspected. I remember a lot of Enceladus illustrations with geysers. One of them was even on Cassini web site (I think). It was also a suspected for the E ring formation as well as Enceladus’ smoothness.

When Voyagr 1 flew by Saturn in 1980, it took rather distant

images of Enceladus which made the moon appear to be

featureless. Scientists assumed the surface was being

constantly remade by cryovolcanoes.

An illustration in a 1981 National Geographic on the Voyager

mission to Saturn depicted liquid water geysering up from an

icy Enceladusian surface and splattering back onto the moon.

Is there evidence of cryovolcanism on Enceladus or any of

the other Saturnian moons?

ljk: I suspect that’s why they’re sending the probe though the top part of the plume, to check for proof of subsurface particle/minerals.

Interesting, Enzo. I hadn’t realized Enceladus had triggered suspicions of geysers back in the Voyager days. Certainly such phenomena would have been a good theory even then for the moon’s visible features.

Just in case, is there any way to tell from the Cassini plume

plunge data if not only organics but actual microorganisms

can be detected, directly or indirectly?

It’s a long shot, but the Universe continues to surprise us

every day.

Long shots are what make these studies so interesting! As for detection of microorganisms with existing instrumentation on Cassini, I just don’t know, but I’m certainly looking forward to the continuing analysis of these new data.

Software ‘hiccup’ undermines trip past Saturn moon

Reuters – EE Times

(03/14/2008 9:28 AM EDT)

“NASA called the problem “an unexplained software hiccup”

that came at a very bad time, preventing Cassini’s Cosmic

Dust Analyzer instrument from collecting data for about two

hours as it flew over the surface of the moon Enceladus

Wednesday.

“A key objective of the fly-by was to determine the density,

size, composition and speed of particles erupting into space

from the moon’s south pole in a dramatic plume.

“Bob Mitchell, Cassini program manager, said the problem

meant that the instrument did not collect data as the craft

flew through the plume — a process lasting under a minute.

“When it went through the plume, it was not working properly,”

Mitchell said in a telephone interview, expressing disappointment.

“We had tested that software very carefully. We don’t know why

it didn’t work properly.”

Full article here:

http://www.eetimes.com/news/latest/showArticle.jhtml?articleID=206903718

I have found this image on Cassini site. I’m pretty sure that it was there

even before Cassini arrived at Saturn :

http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/multimedia/images/image-details.cfm?imageID=603

I used to have a look every now and then, waiting for the long trip to finish…..

Dynamics of Enceladus and Dione inside the 2:1 Mean-Motion Resonance

Authors: N. Callegari Jr., T. Yokoyama

(Submitted on 17 Mar 2008)

Abstract: In a previous work (Callegari and Yokoyama 2007, Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy vol. 98), the main features of the motion of the pair Enceladus-Dione were analyzed in the frozen regime, i.e., without considering the tidal evolution. Here, the results of lots of numerical simulations of a pair of satellites similar to Enceladus and Dione crossing the 2:1 mean-motion resonance are shown. The resonance crossing is modeled with a linear tidal theory, considering a two-degrees-of-freedom model written in the framework of the general three-body planar problem. The main regimes of motion of the system during the passage through resonance are studied in detail. We discuss our results comparing them with classical scenarios of tidal evolution of the system.

Comments: 41 pages, 14 figures. Submitted to Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0803.2264v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Nelson Callegari Jr. [view email]

[v1] Mon, 17 Mar 2008 18:54:49 GMT (1180kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0803.2264

NASA TO RELEASE NEW DETAILS FROM CLOSE FLYBY OF SATURN MOON

WASHINGTON – NASA will hold a news conference at 2 p.m. EDT,

Wednesday, March 26, to present new clues on the composition of the

icy plumes jetting off the surface of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. The

findings were obtained March 12 during the closest flyby of the moon

by the Cassini spacecraft. The briefing will take place in the NASA

Headquarters television studio, 300 E St., S.W., Washington, and will

be carried live on NASA Television.

Participants in the press conference will be:

– Hunter Waite, Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio, principal

investigator, Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer

– John Spencer, Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colo.,

co-investigator, Composite Infrared Spectrometer

– Larry Esposito, University of Colorado, Boulder, principal

investigator, Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph

– Carolyn Porco, Space Science Institute, Boulder, team leader,

Imaging Science Subsystem

Participating NASA centers will provide question-and-answer capability

for reporters.

For NASA TV streaming video, scheduling and downlink information,

visit: http://www.nasa.gov/ntv

Hi Folks;

Since the readership of and commentary to the Tau Zero theads is drawn from regions across the Globe, I thought I would add a personal anecdotal perspective to this rather ordinary, perhaps boring to some, planetary geology story as compared to some of the more exotic and sensational threads posted here at Tau Zero.

Having grown up in and being a citizen of a rather new country (the United States at only about 230 years old) that was founded on the spirit of exploration and pioneerism by the New World Settlers, I was somehow influenced to take a liking to outdoor wilderness vacations, photographs of remote rugged mountainous regions within the U.S., and the thought and desire back in second grade that I would like to be a mountain climber “when I grow up”. Since my father was an active duty Naval officer at around the time of my birth, my parents early on did a lot of traveling by car which included trips of places like Yellow Stone National Park, Yosemiti, the Black Hills of the Dakotas, the Rocky Mountains, and so on. My father had a slide camera as one of his cherished posessions and took lots of pictures.

I remember the slides my father took of the Old Faithful Geyser erupting and how I really wanted to see it one day. Well, to this very day, I have never visited Old Faithful, but I have witnessed something perhaps far more profound, the flight of one of our many robotic space probes through a geyser of extraterrestrial origin. We as a Global civilization are on the verge of doing yet another metaphorical New World Exploration as we send humans back to the Moon by 2020, then to Mars, and then, according to the words of a speech made by President Bush a few years back, ” to worlds beyond”.

Thanks;

Jim

CASSINI TASTES ORGANIC MATERIAL AT SATURN’S GEYSER MOON

PASADENA, Calif. — NASA’s Cassini spacecraft tasted and sampled a

surprising organic brew erupting in geyser-like fashion from Saturn’s

moon Enceladus during a close flyby on March 12. Scientists are

amazed that this tiny moon is so active, “hot” and brimming with

water vapor and organic chemicals.

New heat maps of the surface show higher temperatures than previously

known in the south polar region, with hot tracks running the length

of giant fissures. Additionally, scientists say the organics “taste

and smell” like some of those found in a comet. The jets themselves

harmlessly peppered Cassini, exerting measurable torque on the

spacecraft, and providing an indirect measure of the plume density.

“A completely unexpected surprise is that the chemistry of Enceladus,

what’s coming out from inside, resembles that of a comet,” said

Hunter Waite, principal investigator for the Cassini Ion and Neutral

Mass Spectrometer at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio.

“To have primordial material coming out from inside a Saturn moon

raises many questions on the formation of the Saturn system.”

“Enceladus is by no means a comet. Comets have tails and orbit the

sun, and Enceladus’ activity is powered by internal heat while comet

activity is powered by sunlight. Enceladus’ brew is like carbonated

water with an essence of natural gas,” said Waite.

The Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer saw a much higher density of

volatile gases, water vapor, carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, as

well as organic materials, some 20 times denser than expected. This

dramatic increase in density was evident as the spacecraft flew over

the area of the plumes.

New high-resolution heat maps of the south pole by Cassini’s Composite

Infrared Spectrometer show that the so-called tiger stripes, giant

fissures that are the source of the geysers, are warm along almost

their entire lengths, and reveal other warm fissures nearby. These

more precise new measurements reveal temperatures of at least minus

135 degrees Fahrenheit. That is 63 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than

previously seen and 200 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than other regions

of the moon. The warmest regions along the tiger stripes correspond

to two of the jet locations seen in Cassini images.

“These spectacular new data will really help us understand what powers

the geysers. The surprisingly high temperatures make it more likely

that there’s liquid water not far below the surface,” said John

Spencer, Cassini scientist on the Composite Infrared Spectrometer

team at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo.

Previous ultraviolet observations showed four jet sources, matching

the locations of the plumes seen in previous images. This indicates

that gas in the plume blasts off the surface into space, blending to

form the larger plume.

Images from previous observations show individual jets and mark places

from which they emanate. New images show how hot spot fractures are

related to other surface features. In future imaging observations,

scientists hope to see individual plume sources and investigate

differences among fractures.

“Enceladus has got warmth, water and organic chemicals, some of the

essential building blocks needed for life,” said Dennis Matson,

Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in

Pasadena, Calif. “We have quite a recipe for life on our hands, but

we have yet to find the final ingredient, liquid water, but Enceladus

is only whetting our appetites for more.”

At closest approach, Cassini was only 30 miles from Enceladus. When it

flew through the plumes it was 120 miles from the moon’s surface.

Cassini’s next flyby of Enceladus is in August.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the

European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The mission is

managed by JPL for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington.

For images and more information, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/cassini

The Cassini spacecraft tasted and sampled a surprising organic

brew erupting in geyser-like fashion from Saturn’s moon Enceladus

during a close flyby on 12 March. Scientists are completely giddy

as to why this tiny moon is so active, so hot and brimming with

organics.

Full story:

http://www.esa.int/SPECIALS/Cassini-Huygens/SEMHFYQ03EF_0.html

Are scientists working on this really giddy??

Giddy?

Hi Larry

Does anyone get giddy anymore? Isn’t that something our grandparents felt, particularly the ladies?

Those plumes are blazing hot for something so far from the Sun. Definitely more going on than meets the eye. Dunno if it means Life, but Enceladus has definitely gone up in the AstroBiology stakes.