Sending messages into the galaxy normally goes under the rubric of METI – Messaging to Extraterrestrial Intelligence. In its electromagnetic form, the sending of directed signals to nearby star systems, it has proven more than a little controversial, as the work of Alexander Zaitsev at Evpatoria attests. But sending a message into space in the form of an artifact like the ‘Golden Record’ on the Voyager probes is also a form of METI, and one that excites as much introspection as passion. Larry Klaes has been looking at Trevor Paglen’s Pictures from Earth project, which sends images of our world not to the stars but into a stable orbit near our planet. Who will eventually find these images and what will they make of them? What should we be thinking about when we represent ourselves to the universe?

By Larry Klaes

In the history of humanity, there have been a select number of key events which define the moments when our species became truly intelligent in terms of a self-aware consciousness. One of the relatively more recent milestones is when we perceived a true sense of the future and endeavored to preserve representations of ourselves, along with more direct information, for the appreciation and edification of our distant descendants.

Of course when one attempts to send a message to future recipients, more than just mere illumination is involved: Often enough the creators and senders of the messages into deep time want to show their remote children (or in certain cases, as we shall see, the remote offspring of other intelligences) that they and their society had something of importance to say and offer, that they mattered as much to and in their era as the recipients likely consider themselves to be of value in their own time and place.

Over the ages, the successes and failures of humanity’s efforts at cultural and informational preservation have primarily depended upon a combination of interest, the utilized technology, the education levels of the participants, and especially the location.

For example, much of what we do know about ancient European societies comes from the efforts of Roman Catholic monks and Muslim scholars who spent centuries during the Middle Ages copying and recopying by hand the relatively few surviving texts from the Greek and Roman eras. Outside of those few centers of learning and preservation, ignorance, neglect, and deliberate destruction had turned those once great civilizations into literal ruins and vague cultural memories. Sadly, this has been the fate of most human societies throughout the ages, leaving us with a rather incomplete record of our ancestors’ past.

On Earth, a geologically, environmentally, and biologically active world, even most of structures and objects created by our modern human civilization which survive the next centuries of demolition, discarding, and rebuilding as our societies advance, grow, and endure the vagaries of nature will one day collapse into dust and be buried in a manner of millennia and often less. Certain artifacts deliberately designed to last may survive without becoming fossils for longer than that, but eventually most things built by our minds and hands will turn into mere remnant artifacts at best. Our biological remains will disappear from the natural historical record even sooner, except for those which are “lucky” enough to be fossilized or artificially preserved.

The ability to preserve aspects of ourselves changed dramatically once we were able to directly access space starting in the 1950s. Artificial objects in the celestial realm are subject to far less erosion and other debilitating factors than on the surface of our ever-changing planet. In the Sol system, a spacecraft might last for many millions of years sitting on the lunar regolith or drifting around our sun in interplanetary space. A vessel sent into the even calmer and emptier reaches of interstellar space is expected to remain intact for one billion years or more. All of these factors involve vehicles and equipment which are protected from the space environment primarily for the duration of their missions. Anything after that is considered a bonus.

It is this feature of very long-term existence beyond Earth which intrigued New York geographer, independent scholar, and photographic artist Trevor Paglen to create an art project and a deeply deep time artifact he named The Last Pictures.

Way Up in the Middle of the Air

While working on another photographic art composition about military reconnaissance satellites, Paglen learned that vehicles which occupy a special region 35,786 kilometers (22,236 miles) or so above Earth could stay there in space virtually until Sol stops producing hydrogen in its core and its outer atmosphere bloats our sun into a red giant star about five billion years from now. Anything still surviving in orbit around Earth in that distant future era will surely be vaporized even if our sun does not engulf our planet as is currently predicted.

Image: Trevor Paglen, the force behind The Last Pictures. Credit: Creative Time/University of California Press.

Before that cosmic demise arrives, however, an object existing in what is known as both geosynchronous orbit and the Clarke Belt (named after science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke (1917 to 2008), who in 1945 popularized the potential global uses for satellites in this region) can remain up there for eons.

While natural phenomena such as meteoroids, solar flares, and cosmic rays can damage these artificial residents over time, the primary element of demise they will remain untouched by is Earth’s atmosphere. Although the outermost layer of air, known as the exosphere, extends through and beyond the Clarke Belt to eventually merge with cislunar space, the sparse amount of hydrogen and helium atoms that compose the exosphere mean that satellites this far from Earth are not subject to atmospheric drag. Vessels in lower orbits encounter relatively thicker regions of air, which cause them to eventually lose their orbital velocities and descend towards our planet to end their existences as meteors.

Nations and corporations place satellites in geosynchronous orbit to utilize the fact that an object at that height can match Earth’s 24-hour rotation rate. Such satellites appear to hover over one spot above our planet. This feature and their very high vantage point allow just three satellites spaced around Earth to provide electronic communications for almost the entire global community.

The first satellites to successfully take advantage of this special orbit were the Syncom (short for “synchronous communication satellite”) series launched in the early 1960s. Decades later, hundreds of communications satellite, or comsats, now circle our planet scattered throughout the Clarke Belt, conducting a wide variety of commercial and military needs. They are such a regular and vital part of our modern technological civilization that most people do not even think about the services comsats provide in our everyday lives, or even the existence of these mechanical stations themselves.

Image: Mission patch for The Last Pictures. Copyright Trevor Paglen.

Paglen became fascinated by the fact that these comsats might be among the last bits of evidence that humanity ever existed. The artist imagined an advanced alien intelligence arriving in the Sol system in some remote future time and encountering this “man-made ring of Saturn forged from aluminum and silicon spacecraft hulls.”

Between the methods of terrestrial erosion and his general pessimism over the long-term survival of humanity, Paglen decided to create a work that would be capable of lasting for ages, far from the corrosive potentials of both our planet and our species.

Inspired by the Pioneer Plaques and the Voyager Interstellar Records which left Earth in the 1970s to become humanity’s first physical messages to the wider Milky Way galaxy, Paglen put together one hundred carefully selected photographs he called The Last Pictures and had them nano-etched onto a disc composed of silicon and ceramic. The disc was then encased for protection between two interlocking gold-plated aluminum covers, one of which has a “temporal map” etched onto its exterior. Using the language of science, this diagram should provide the finders with a method to determine the approximate era when Paglen’s art work was created and sent into space.

The complete piece is known as the EchoStar XVI (16) Artifact, named after the latest communications satellite in its series that carries this message to future places and beings. The artifact was successfully sent on its journey into space and time atop a Russian Proton-M/Briz-M rocket launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on November 20, 2012. Information and images of the satellite and its launch may be found and seen here. The primary mission of this 6,258 kilogram (13,796 pound) comsat is to provide television broadcasts for the next fifteen years for the millions of customers of the Dish Network Corporation living in the United States.

Image: Launch of EchoStar XVI. Credit: Space Systems Loral/International Launch Services.

When EchoStar XVI approaches the end of its initial career as a comsat around the year 2027, ground controllers will command the satellite to fire its thrusters. This event will move EchoStar XVI several hundred kilometers further away from Earth into what is known as a “graveyard” or supersynchronous orbit. Here is where many past geosynchronous comsats “go to die”, to use a phrase. This realm for the older, obsolete satellites gives the next generations of comsats the important room they need to function in the relatively narrow and highly prized technology zone far above our planet and the civilization which is quite dependent on these machines.

Once EchoStar XVI and its attached artifact reach their second home in space and the comsat is subsequently shut down, that is when this satellite and its atypical cargo begin their next tasks — as keepers of perhaps one of the final messages to future humanity, or beings from other worlds, or to the vast and unaware Universe far beyond Earth’s geosynchronous realm.

Discovering The Last Pictures: Initial Impressions

I learned about The Last Pictures art project rather recently by chance. I was perusing the science and nature section of a local bookstore when I came across a book on display: Its cover depicted the famous Earthrise from lunar orbit photograph taken by the manned Apollo 8 mission in December of 1968 and those three provocative words printed across the blackness of space in which our planet was and is embedded.

It did not take me very long to realize I was looking at something I and others have been advocating for quite a while now with Faces from Earth: Someone had put together a collection of photographs representing humanity – or at least their take on the subject – and put them aboard a space vehicle to endure for ages, to be seen by natives of the far, far future, if ever.

Paglen was influenced by the engraved plaques put aboard the Pioneer 10 and 11 robotic planetary probes, which were launched from Cape Canaveral in Florida in early 1972 and 1973, respectively. They were the first spacecraft to flyby the gas giant worlds of Jupiter and Saturn, where their massive bulks in turn flung the two probes out of the Sol system.

Etched onto a gold-coated plate of aluminum, the relatively basic messages on the Pioneer Plaques show where the probes came from using a pulsar “map” and a diagram of our Sol system, with a simple image of the Pioneers flying from Earth to pass between Jupiter and Saturn and then into deep space. The plaques also depict the species which built them, represented by a nude and pan-racial male and female human. The man is holding up his right arm and extending his hand in what was hoped would be interpreted as a friendly gesture of salutation.

Whether the Pioneers and their “calling card” bolted to the antenna struts would ever be found by anyone roaming the Milky Way galaxy in a remote future epoch, let alone interpreted correctly, was unknown; what mattered even more is that humanity had created machines which could explore distant planets and then leave our celestial neighborhood. That some folks recognized these milestone feats and commemorated them in some fashion was a wonderful bonus, a sign that human beings were finally becoming aware of the true nature of the wider Cosmos around them and our overall place in it.

Paglen’s other influence for The Last Pictures were the expanded “sequels” to the Pioneer Plaques, known officially as the Voyager Interstellar Records but referred to by Paglen and others, not inaccurately, as the Golden Records.

Far more than just a pictogram on a rectangular piece of metal, the records had images, sounds, languages, and music, as much as a representation of the builders of the Voyager 1 and 2 probes and their world could be placed into the grooves of a 12-inch phonograph disc. The more sophisticated Voyagers, launched just weeks apart in 1977, examined all four of the outer planets, many of their moons, and their ring systems before gravity and physics sent them hurtling into the galactic void as well.

Both of these early physical Messages to Extraterrestrial Intelligences (METI), as such efforts are now called, were created and produced by a select group of individuals headed by Cornell University astronomer and science popularizer Carl Sagan (1934 to 1996) and his colleague and Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligences (SETI) pioneer Frank Drake. Sagan’s second wife, Linda Salzman Sagan, was the artist for the Pioneer Plaque and later worked with Timothy Ferris, Jon Lomberg, and Ann Druyan on the Voyager Records. They took it upon themselves to initiate and anoint the probes with these interstellar information packages when NASA showed no initial formal interest in affixing so much as a commemorative token to the first human-made vessels ever to escape the gravitational confines of the Sol system.

The plaques and records were designed for intelligent and technologically advanced beings from places other than Earth, to hopefully give them some idea about the makers of the likely very ancient vessels drifting and tumbling silently through interstellar space. Of course the odds are somewhat better that their remote finders will be the descendants of humanity itself, having successfully survived their species’ biological and cultural adolescence to explore and colonize the Milky Way galaxy. No doubt our children would appreciate these rare artifacts from the days of their forefathers’ first steps into the Cosmos.

As much as I was excited by the discovery of The Last Pictures, I must admit an initial bias: As I conducted my initial scan of the book at the store, noting especially the one hundred black-and-white photographs that are the heart of the project, I was concerned that what had been created was yet another bit of modern art which was more pretentious than meaningful and born of true artistic talent. I also confess I was not previously familiar with the artist Paglen or his work, which surprised me a bit considering his earlier work with photographing military satellites and their often secret mission patches and other classified government operations, such as this one. While I certainly know and appreciate that many modern artists and their works can be just as good as anyone and anything from the classical periods, I often sometimes balk at pieces I see in galleries and museums that look more like someone accidentally spilled paint on a canvas or left a pile of scrap metal to rust in a vacant lot. Then they have the nerve to add insult to injury by charging ridiculous sums of money for these claims to higher culture.

Fortunately, as I began to examine The Last Pictures in detail and read about how the project came to be, it did not take long to realize that Paglen put a lot of thought, effort, and feelings into this message-gift to the far future. He spent over five years assembling and managing a team from a wide range of disciplines to offer their insights and resources to the project. This is exactly or closely as possible to what all METI efforts should have and be like when assembling their information packages to the stars.

Of course Paglen was fortunate in a number of regards. One of them was his choice of spacecraft upon which to place the artifact: A geosynchronous communications satellite. They are far more commonly available in comparison to deep space probes like the Pioneers and Voyagers.

Over eight hundred comsats have been built and aimed for that specialized high Earth orbit since 1963, whereas only five robotic probes (and their final rocket stages) have flown straight out of the Sol system since the dawn of the Space Age. If one comsat was not available for the art project, another one would have eventually come along relatively soon for Paglen to utilize.

In contrast, the Voyager Record team was small in number, largely self-motivated, and had only a few short months between when NASA approved placing a physical message aboard the Voyagers and completing their METI project before the two probes would have to be launched: In order to precisely fly by the four outer giant worlds in just one decade per the modified “Grand Tour” mission plan, the Voyagers had to be sent up on certain days in the late summer of 1977 or miss a rather special “window” in space that would not come again for another 176 years.

Ironically, one of the photographs in the EchoStar XVI Artifact displayed a project developed by the famous married team of Charles and Ray Eames which they created for the American National Exhibition held in Moscow in 1959 titled Glimpses of the USA. During development, the Voyager Record team had approached the Eames, who were well known for their elaborate exhibits and films explaining science, technology, and history among other subjects to the general public (such as Mathematica and Powers of Ten), for assistance in putting their own educational project together. The Eames replied that such an undertaking would require years to be treated properly and subsequently dismissed Carl Sagan and his collaborators.

The Eames may have been right to a point, but as we have already seen, the Record team did not have the luxury of abundant time or resources. Charles and Ray probably would have preferred and approved of how Paglen conducted his project, as there are definite similarities between the two artists’ styles. In any case, I say both projects have their merits and our civilization is fortunate that they exist at all. We should be grateful that there are people and societies who are willing and able to create and support such an idea. These acts raise us above life and culture being just mere survival and other baser instincts.

One Hundred Photographs, Two Cultures

Although the EchoStar XVI Artifact can definitely count the Voyager Interstellar Record among its inspirations and influences, that project was a largely science-based effort to represent a cross-section of late Twentieth Century humanity and our celestial home to potential others in the Milky Way galaxy. The core of most of the one hundred images of The Last Pictures art project is predominantly about contemporary social commentary on the state of our species viewed through the prism of the artist.

As revealed from this quote in an article about the project in the November 30, 2012 edition of The Atlantic magazine, Paglen’s overall intentions and ambitions for The Last Pictures appear to be diametrically opposed to the purposes of the Voyager Records by Sagan and company:

Even after the satellite goes dark, The Last Pictures will remain in orbit until the Earth as we know it no longer exists — or until a new civilization, human or otherwise, finds it. “This is not a project that’s supposed to explain to aliens what humans are all about and be the definitive record of human civilization,” Paglen tells The Atlantic. “It is a collection of images that explained to somebody in the future what happened to all of the people who build the dead spaceships in orbit around the Earth. And how they killed themselves.”

However, as we will see, both METI projects dabbled — deliberately and subconsciously — with the other side of their focus, which British chemist and novelist C. P. Snow identified in his now famous 1959 lecture as “the Two Cultures” of the sciences and the humanities, or liberal arts. Once treated more-or-less evenly by Western culture from ancient times, the two disciplines were generally split apart with the rise of the Enlightenment. Since then there have been numerous efforts to reunite these cultures and their practitioners, or at least to gain a better appreciation for them by one side for the other. Paglen’s space-based art exhibit on indefinite “display” is among the latest serious attempts to build a bridge between these two worlds.

Nevertheless, the predominance of art and the humanities over science with the EchoStar XVI Artifact can be seen with its very first photograph. For the Voyager Record, the initial image was a simple black line circle against a white background, designed to show the finders the proper calibration for viewing the rest of the 118 photographs on the golden disc.

The Record team did not want to assume that the finders would quickly and easily grasp how to view their information, even if the instrument they stored their images on would be relatively simple to operate for beings that could travel between the stars and find such a small vessel among the immensities of the Milky Way.

In stark contrast, the EchoStar XVI Artifact’s first image is of the label on the back of a watercolor work created in 1920 by the Swiss-German painter Paul Klee (1897 to 1940). Titled Angelus Novus (New Angel), the most well-known (one could go so far as to say dominating) interpretation of the meaning of the front of this piece is by the German Jewish philosopher and literary critic Walter Benjamin (1892 to 1940), who purchased it in 1921.

Benjamin said the following about Klee’s work in his ninth thesis in the essay “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, which is repeated in the companion book:

“A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

For a look at the side of Angelus Novus not sent up with The Last Pictures, along with a different take on the watercolor and Walter Benjamin’s view of it, visit here.

So is Paglen’s act of turning the artwork around saying that Klee-Benjamin’s “angel of history” is now facing the future that the EchoStar XVI Artifact is journeying into? A distant future which Paglen sees and describes throughout his book as one which will not be occupied by humanity due to our destructive natures. Clearly we are well outside the scientifically designed and deliberately simple opening pictorial messages of the Voyager Record.

While the Benjamin-focused symbolism of Klee’s actual work may be relevant to the central messages Paglen is attempting to convey to contemporary folks and whoever exists in the far future (both Paglen and Benjamin do and did not see progress as a necessarily good thing for modern humanity), I also get the impression that this particular art piece is Paglen’s way of paying recognition — perhaps even capitulating to a point – to his fellow professional post-modern and avant-garde artists. A number of them expressed attitudes ranging from ambiguous to dismissive about this project as both actual art and any kind of real message to anyone in the future, human or especially alien.

Part of this reaction from select members of Paglen’s peers could be due to sheer professional jealousy. Paglen received a lot of support and publicity across multiple disciplines as he spent almost half a decade developing The Last Pictures. Having the final results of his efforts literally rocketed into the heavens — bolted to a commercial communications satellite, no less — must have seemed extravagant to a community that generally stays on the humanities side of the cultural fence. That no one in this generation and for likely many more to follow will ever see the actual photographs again must appear paradoxical, even an affront to the post-modern art world, where even they insist that an artist’s work at least be somehow visible to them and any interested members of the general public.

There is, of course, the official book with all the photographs along with their explanations and the history of the project, and Paglen went on a lecture tour to various cities around the globe displaying and discussing his artwork, but that is not quite the same thing.

Even if the actual artifact were physically accessible to people on Earth, one would need a magnifying glass or something stronger to see the tiny collection of pictures, which sit on a thin wafer of silicon roughly the size of an old U.S. silver dollar coin. That The Last Pictures would also be sitting on the surface of our planet and thus be subject to the mercies of human nature and the rest of terrestrial nature defeats the purpose and point of its existence in the first place.

I also think that by showing the back of a painting (and then sending it into space indefinitely), Paglen is imploring his colleagues, and, by default, the rest of humanity, to think outside the box of what our culture calls art, be it modern, classical, or any other labeled form. Art does not have to be confined to some gallery or park, nor should it. Instead it should reflect and comment upon the society which creates it. Certainly The Last Pictures succeeds in this goal to a literally high level.

As for the “literally high level” of the art, Paglen is also attempting to get people to think outside the spherical box called Earth and their even smaller places upon its surface. For despite his overall comments in the book and through interviews expressing discouragement about the fate of his species and his civilization, Paglen’s artistic gesture is ultimately a warning and a wakeup call – and those are usually not done unless there is a sense of hope and concern to keep us from the path to degeneration and extinction – even if Paglen does not quite see it or admit it to himself.

Space Age Cave Paintings

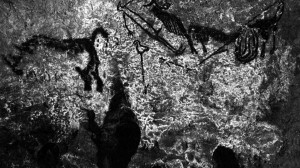

The key piece of The Last Pictures is among the most ancient surviving renditions of human-made art, the Upper Paleolithic cave paintings at Lascaux in southwestern France. Archaeologists estimate they were made between fifteen and eighteen thousand years ago, millennia before the first true civilizations appeared anywhere on Earth. Paglen included in his little art show two different scenes from the walls of Lascaux cave and one other example of rock art: The latter one is actually a much more recent series of Native American petroglyphs whose symbols and messages are clearly understood by modern archaeologists.

Paglen chose a particular section from Lascaux located in what is called “the Pit” or “the Shaft of the Dead Man” section of the cave. Painted on the yellowish mineral surface is what appears to be a bison, possibly injured from a hunt, attacking a stick figure representing a man, while a prehistoric rhinoceros is shown walking away nearby. Next to the man is a bird on a long stick. Of the over two thousand representations on the cave walls of Lascaux, this is the only one to clearly show a person.

Image: Lascaux cave art from The Last Pictures. Credit: Creative Time/University of California Press.

What exactly this scene and the rest of the Lascaux paintings mean and why they were created has been a subject of wide and intense debate ever since they were discovered in 1940. Theories have ranged from straightforward pictorial recordings of real events to efforts at “sympathetic magic” to ensure good hunting to depictions of constellations and other celestial objects. The interesting and frustrating aspect of these serious suggestions for the paintings is that all of them are plausible as much as our separation from these ancestors in space and time and a lack of written or even oral records allow.

Paglen explores the Lascaux painting extensively in the companion book, devoting much of Chapter 2 to the ancient artwork. As he explained in a recent interview with e-flux journal:

“Cave paintings are an example of images or records we have from cultures that have been radically torn from any historical context. They are to us what our spacecraft may be to the future. I actually think about The Last Pictures as cave paintings for the future.”

Incidentally, the Pioneer Plaques have also been referred to as “interstellar/intellectual cave paintings” pretty much from the time they were created by such folks as Eric Burgess who co-authored Pioneer Odyssey: Encounter with a Giant (NASA SP-349), the official publication by the space agency on the Pioneer 10 and 11 probes. Even though the METI artifacts that have been sent into space were manufactured as deliberate carriers of information for minds that may bear only the slightest resemblance to ours, they too may become the subject of intense debates over their true meanings as wide ranging and just as plausible as any ancient terrestrial cave art. Almost certainly the time between their creation and their discovery will be much longer than the chronological distance between our era and the Paleolithic. How wide the gap will be between our minds and the recipients’ and if it can be bridged in any capacity is another matter.

Of Optimism, Pessimism, and Convergences

For the most part, one can rather easily be forgiven for thinking that The Last Pictures is primarily an early Twenty-First Century artistic response/mirror to the Voyager Records made 35 years earlier in the late Twentieth Century. Most of those who commented on the Records in relation to Paglen’s art project, including the artist himself, portray the construction of the Golden Record, those who put it together, and even the era in which this physical METI was made as overly optimistic, especially towards the future in which the shining grooved disc was intended for.

Unfortunately for us, a positive and progressive view of the future has often been seen as both naive and retro since the time of the Voyagers (and often before) in various cultural circles, thanks ironically to a growing awareness of the negative effects human civilization has had on our planet’s environment and society. Our cultural and technological problems have often seemed insurmountable in the past and thus the rejection of a bright and shining future and anything that goes along with this view. Whether we become the makers of our own perceived demise has always been up to us, guided by our own mental and educational limitations, biases, and fears.

Now granted, the Record was designed with the intent of putting humanity’s “best foot forward” as declared multiple times in the wonderfully detailed book all about the Record authored by the key members of the creative team titled Murmurs from Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record (Random House, New York, 1978). While the team certainly knew that the human species and its history was hardly full of saints and noble acts of enlightenment, they decided not to show our pollution, poverty, and warfare in this act of introduction to the rest of the Milky Way (or at least some part of it), no more than one who is first meeting a potential friend and ally would start things off by telling them all about their problems and such. There would be the chance that the other person might not be shocked and offended by such an overt act, but it is better not to risk a negative reaction.

Perhaps there are cultures and species which would consider not addressing one’s flaws and other issues up front to be an offending deception, but that in turn would be a deception of the culture that made and sent up the Voyager Records. With these early, tentative METI efforts heading off into a galaxy with so many unknowns, it is probably best to keep the metaphorical waters as clear as seemingly possible.

As I write these words, I am also reminded of the lesson I acquired from several college anthropology professors who said that they and the other members of their field often learned more truth about other cultures by digging through their garbage dumps than any of their monuments or official records. That being said, perhaps the only access beings from other worlds will have of humanity are these few token efforts at conveying something of ourselves. The complexities and potential issues of cultural “dumpster diving” may never come up, though technically we could load every bit of information about humanity and our world onto various types of storage medium that could be affixed to a space probe.

Or perhaps, as Paglen envisions, those who find a Pioneer Plaque, a Voyager Record, or one of our electromagnetic transmissions will be interested enough to search us out, coming upon a future Earth where all that is left of humanity are our terrestrial ruins and that artificial ring of geosynchronous satellites, with one of them having a particular golden artifact bolted to its pitted hull. In that scenario, about all that would be left for the visiting ETI to do in terms of learning about us would be grand-scale dumpster diving.

After all, in the case of the Voyagers, the situation will very likely involve a receiving party that is neither human nor familiar with contemporary Earth encountering a derelict and unfamiliar vessel deep in the cold and dark of interstellar space. While one might presume that intelligences that can ply the starways are sophisticated enough to recognize a probe that is ancient, comparatively primitive, and non-hostile (not to mention non-functional), even if both sides are quite otherwise alien to each other, why take the chance of provoking an unknown species in an unknown situation – which in our current case is the vast majority of the galaxy and beyond!

This line of reasoning is why the Voyager Record team did not include images such as the mushroom cloud from a nuclear bomb detonation. While such a display of weaponry might seem pathetically crude to an interstellar level civilization (assuming they even understood what the artificial cloud signifies), it might still be taken as a feeble threat to be acted upon, either through avoidance or removal of the source.

In contrast, The Last Pictures does include a photograph of an ocean-based atomic weapons test from the early days of the Cold War: A huge mushroom cloud composed of seawater and other debris rises and expands over a fleet of decommissioned military ships placed there purposely to see how such vessels would fare during a nuclear attack. While this picture is primarily part of Paglen’s commentary on humanity’s self-destructive nature, I cannot help but think he also purposely included this selection as an opposing tweak to the perceived culturally “scrubbed” and optimistic framework in the Voyager Records.

The photograph of a Vietnamese family whose children were deformed by Agent Orange is another double-edged message in regards to the Voyager Record, which showed a humanity that is racially and culturally diverse but included none of its overt flaws. However, to note, there is one photograph from the Record which does deliberately attempt to display to its finders that we are not perfect beings: A bright orange snowcat vehicle from a 1958 expedition to Antarctica is shown hanging precariously over an opening in the ice sheet, seemingly ready to plunge into the dark chasm with any wrong move from the team members standing just behind it. While hardly as shocking an image as the children or several other items among The Last Pictures, its sheer incongruity among the photographs on the Voyager Record has at the least given it the chance of standing out to get its own message across in the same manner as Paglen’s representations of his own species.

Image: Antarctic image from the Voyager ‘Golden Record.’

Now despite all of the claims and efforts by the artist to specifically contrast the messages of the one hundred images in The Last Pictures from those 118 photographs engraved in the Voyager Record – especially when it came to explaining what it all means without resorting to a straightforward scientific underpinning – it is obvious to any student of the Record that Paglen did indeed take more than just cues from that METI predecessor and role model in an attempt to clarify the nature and origin of the EchoStar XVI Artifact to its potential finders.

Similarities may be found among the first row of photographs (A thought: Will the discoverers of the Artifact know which way to properly look at the images?). There is an image of a rocket launching at night and another of Earth in gibbous phase as seen from high above our Moon.

While the rocket, a Soyuz FG, is not exactly of the same model that did loft EchoStar XVI and its Artifact into orbit (Proton-M/Briz-M), it is of a fairly similar design and from the same country of origin (and both were sent into space at night from the same space center). Sagan and his companions included an image of a Titan-Centaur III rocket launch from Cape Canaveral (carrying a Viking lander on its way to Mars in 1975) on the Record, the same kind of booster combination that subsequently sent the twin Voyagers on their way to the outer Sol system and beyond in 1977.

Image: A Soyuz launch from The Last Pictures. Credit: Creative Time/University of California Press.

The basic message in both cases is to convey the type of conveyance that got the satellite where it will most likely be found one day. I like to imagine that a chemically-fueled rocket of any make or model would seem quite crude to whoever finds their payload, be it future humanity or an extraterrestrial intelligence. Of course this assumes that alien beings also used similar vehicles to initially venture to the stars. Perhaps they decided early on that riding a long metal tube encasing a series of controlled explosions was a barbaric and suicidal method of reaching space and started off with a space elevator, a much more sedate if more complicated means of transportation. Or maybe most everyone had to go with rockets to get out of the deep gravity wells of their home planets.

As for the images of Earth, the Voyager Records contain several photographs of our planet from space. One in particular shows our world from far away as witnessed by the astronauts of the Apollo 11 expedition, the mission that placed the first humans on the lunar surface in July of 1969 and the one that followed Apollo 8, the mission which had placed the first people about the Moon just seven months before and whose iconic visage of humanity’s home planet is part of The Last Pictures. At the risk of being obvious, whoever does find the EchoStar XVI satellite in geosynchronous orbit and comes upon the golden disc of the Artifact and its contents will only have to look at our world from their vantage point to get a good and rather quick idea as to where this ancient relic came from.

Two other parallels between the METI disc photographs sets are the Great Wall of China and an astronaut conducting a bit of Extravehicular Activity, or EVA. Whereas the Voyager Record used an image of the first spacewalk by an American astronaut, specifically Edward H. White II during the Gemini 4 mission in 1965, Paglen included one of the first Soviet cosmonaut to EVA, Alexey A. Leonov, who beat White to this task by three months during the Voskhod 2 mission. Incidentally, Leonov went on to become an accomplished artist and author, painting space themes both real and imagined.

Paglen did cop one photograph directly from the Voyager Record, the depiction of how humans consume nutrients by variously eating, drinking, and licking it. That the artist chose this image is no surprise from an artist point of view: The scene has an almost Daliesque quality to it, one the famous surrealist artist might have appreciated. While it was initially created to show how our species gets food and liquid into our bodies, the need to make this activity distinctly clear in the photograph made for somewhat bizarre and humorous results, at least from our contemporary perspective. I appreciate that Paglen’s description of this image in his book included an update on what became of at least two of the three Cornell folks who volunteered for this photograph, along with further insights on their stories and thoughts on the event.

Image: Typical human activities as included in The Last Pictures. Credit: Creative Time/University of California Press.

A Few More Observations

I was personally pleased to see that Paglen had included one of the diagrams depicting the famous (or infamous, depending on your point of view) Canals of Mars, first noted by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli in 1877 and not fully accepted to be optical illusions until robotic space probes began imaging the Red Planet up close nearly one century later.

This particular sketch of the Martian canals was made by the Boston astronomer Percival Lowell, perhaps the biggest supporter and promoter of the mysterious lines across the faces of the fourth world from Sol. His view that astronomers were witnessing the works of a superior native race who were trying to save themselves on a dying globe by bringing water from the Martian polar caps to their cities via this massive network of canals would influence our perspectives on the Red Planet in many ways to this very day. This includes our continued efforts to search for life there even in its most rudimentary forms, whether still in existence or as fossils.

As a quite relevant example of how our fascination with the potential for Martian life carries on long after space science revealed the fourth world from Sol to be a seemingly barren world biologically, Paglen included in The Last Pictures the famous electron microscope image of one of the “microfossils” found in ALH 84001, a meteorite from the surface of Mars discovered in Antarctica in 1984 and publicly announced by NASA twelve years later as having possible evidence of past life on the Red Planet. Whether humanity holds in its possession the first recognized evidence of alien organisms is still being debated by the scientific community.

I see the inclusion of Lowell’s drawing as a commentary on the current state of our understanding on extraterrestrial life on the galactic scale, which in many respects is no better or worse than how Lowell and his contemporaries viewed Mars over a century ago. Perhaps this is also Paglen’s way of saying that he thinks alien beings are no more plausible than the Martians Lowell believed were responsible for the nonexistent canals. Or perhaps they do exist but are not at all what humans can even imagine. Ironically, Lowell was considered to be a rather poor draftsman when it came to his canal drawings, though the books he authored on his favorite alien planet were well written.

The other tribute to humanity’s ideas and hopes on alien intelligences found in the collection is the printout of the famous Wow! Signal. Members of the Ohio State University (OSU), who had been conducting radio SETI with their Big Ear radio telescope since 1973, found themselves in a potential state of good fortune on August 15, 1977, when OSU astronomer Jerry R. Ehman noted a rather strong narrow-band signal on a printout from an observing run. He circled the alphanumeric code on the paper in red pen and wrote the word “Wow!” next to it, thus giving the event its name.

Whether the Wow! Signal was an actual transmission from an ETI or just terrestrial interference has never been fully determined. The signal did not repeat and numerous searches for it in the years since have turned up empty. Nevertheless, the Wow! Signal served as a prime example of how we thought an alien civilization might attempt to communicate across the Milky Way galaxy. The image of the printout may make no more sense to the Artifact finders than the photograph of the page of randomly generated numbers; however I am still glad that Paglen decided to preserve this important piece of SETI history.

As a side note, simply because I find it interesting: Voyager 2 was launched on its way to the outer Sol system on August 20, 1977, just five days after the Wow! Signal was detected. Elvis Presley died the day after the Wow! Signal appeared and Groucho Marx passed away the day before Voyager 2 was sent into deep space. I cannot help but be reminded of the comment in the 1997 science fiction film Men in Black, which tells about a super secret organization that deals with alien refugees hiding on Earth, that Elvis did not die, “he just went home.”

Among the possible reasons that Paglen included a photograph of a dandelion flower gone to seed is that it is a nod to Carl Sagan, the key person behind the Pioneer Plaques and Voyager Interstellar Records and the co-creator and host of the famous Cosmos science series that premiered on PBS Television in 1980. Sagan utilized a wind-transported seed (from a milkweed plant, I believe) in Cosmos to start off the series by having the seed rise up into the celestial firmament and transform into the Spaceship of the Imagination, which took Sagan and his vast audience via special effects to any place in the Universe that each episode focused on. Lastly, the animated logo seen in every episode of Cosmos released on DVD by Carl Sagan Productions is of a cluster of dandelion seeds on a stem being blown to the stars.

The Temporal Map

Another place where the Pioneer Plaques and Voyager Records had their influence on The Last Pictures is on the outward-facing half of the gold-plated aluminum covers protecting the silicon disc with the photographs. Unlike its aforementioned predecessors, the EchoStar XVI comsat which the Artifact is attached to will be staying in a very wide orbit about its home planet indefinitely. Since it is considered rather obvious as to where the satellite came from, Paglen focused on attempting to inform the Artifact finders as to when EchoStar XVI was built and launched into space.

As with most serious previous efforts to communicate with ETI, Paglen opted to use the language of science as the best chance for the Artifact’s finders to comprehend the place in time where those one hundred little photographs came from, along with the big derelict satellite it is connected to. Initially, however, Paglen did not intend to go this route, as he says on page 18 of the companion book:

“I always thought the [Artifact] cover would be something deliberately surrealistic, a nonsensical image or pattern. At one point I thought the cover should be an image of a tall, goat-headed man towering over a startled child. But as the deadline for the final design got closer and closer, I started to have a dramatic change of mind. At another, I thought the cover should bear a simple inscription: ‘Please do not disturb me. Let me stay here so that I may witness the end of time.'”

Enlisting the help of astronomer and physicist Joel M. Weisberg from Carleton College, Paglen put together a temporal map. As explained in their paper on the EchoStar XVI Artifact cover etching, this map is designed “to indicate the spacecraft’s Epoch of Origin using currently measured quantities such as the South Celestial Pole location, Earth’s stellar rotation period, location of tectonic plates, orbital period of the Moon, locations of stars and extragalactic radio sources, and positions and periods of pulsars.”

Along with the pulsar maps employed on both the Pioneer Plaques and the protective cover of the Voyager Records, Paglen and Weisberg used their representation of the ground state transition of neutral atomic hydrogen as a fundamental unit of time. Not only is hydrogen easy and simple to replicate as a diagram, it also happens to be the most abundant element in the Universe. It should be readily recognizable to any beings that can travel through deep space and dwell far in the future.

As the art project was under development, several people protested this method of talking to unknown intelligences in the far future. Prominent among them was Rafael E. Nunez, a cognitive scientist from the University of California at San Diego. Nunez sees all mathematics as subjective: Any mathematics on the Artifact cover would be as useless for proper interpretation as a pattern of random scratch marks to an alien species and even humans from a different culture.

Nunez even gets to state his case in Chapter 4 of the book, mocking the statement made by the character of SETI scientist Ellie Arroway about “mathematics [being] the only truly universal language” in the 1997 film version of Carl Sagan’s only science fiction novel, Contact, (the ETI who contact humanity in Sagan’s work use the first one hundred prime numbers, which are digits divisible only by themselves and one, to get our attention, as no known natural phenomenon makes such a signal). Nunez goes further to say that aliens themselves, because “no actual forms of extraterrestrial aliens – dead or alive – have ever been documented empirically, such beings are, scientifically, nonentities…. Aliens, as we know them, are the product of human imagination.” The professor sums up his essay in the companion book that “if we want to believe that talking mathematics to aliens makes sense, we must humbly accept that we are anthropomorphizing, big time.”

Despite Nunez being “visibly annoyed” about the plan to put a star map on the EchoStar XVI Artifact cover, Paglen ultimately defended the idea thusly:

“If we make a star map, and no one ever finds it, then we’ve lost nothing. If we make a star map, and someone does find it but cannot interpret it, then we also haven’t lost anything. But if we’re wrong and they can interpret it, the star chart might make them very happy. It might truly be a treasure.”

Nunez would eventually go along with Paglen’s idea as a thought experiment, helping the artist to decide on the “calibration” shapes for the cover. They ultimately chose two geometric patterns that would hopefully teach the map notations to its potential finders: A “right triangle whose sides are 1, meaning its hypotenuse is the square root of two” and “the proportion of the area of a circle to a surrounding square – a figure chosen because, unlike transcendental numbers such as pi and e, it has absolutely zero metaphysical baggage.”

Paglen’s numerous comments to the contrary in his book and elsewhere, to me this shows that he at least hopes someone will find the Artifact some day, which in turns says that the artist thinks humanity will last long enough to perform such a feat. Either that or another more successful intelligence will fulfill his underlying agenda. Certainly Paglen wants his fellow contemporary humans to note his work and its messages, otherwise why go to all that effort, time, and money? Paglen is not quite that avant garde.

As for Nunez, while I understand why Paglen would choose this particular professor as a sort of “devil’s advocate” to again make sure he is not appearing too much like an optimistic and scientifically rational Carl Sagan of the 1970s, I found the cognitive scientist to be a bit too much of a naysayer for this kind of a project.

Yes, mathematics may be subjective and therefore incomprehensible to even humans too far separated by culture and time, let alone minds from another world. Yes, we know of no other actual alien beings at present via empirical science and what we think are even our best ideas on the subject are based on our experiences with other life forms strictly from a single planet, Earth. It is also a given that most professionals across the board who want to be taken seriously by their peers and relevant authority figures do not want to be too closely associated with the idea of aliens, thanks in no small part to the centuries of subpar science fiction stories on the subject and the fringe elements that have come from the UFO phenomenon and its related subcultures. Nunez makes sure to slam home his stance by twice lumping aliens in with “angels, phantoms, [and] Donald Duck” along with the dig at Sagan, the most prominent member of the Voyager Record team, via his novel and film Contact. I was a bit surprised that those old standbys, Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster, did not get included in his list of mythical creatures.

However, if you are going to create and send an actual message into the future either for ETI or your distant children (who may become more alien to us than we are to Homo habilis, as an example), you need to “bite the bullet” and come down on certain lines rather than stay up in the clouds of subjectivity which are always safer in terms of potentially being wrong and ridiculed for making a particular declaration despite imperfect evidence. The same goes for conducting SETI/METI and interstellar travel: Either we attempt to learn what is out there in the rest of existence by making a real effort to know using the tools we have now, or we get bogged down in a sea of philosophical ramifications and ultimately lose our momentum and drive, which will lead to us losing the reason our species is what it is and got as far as it has in the first place – even if it is that dreaded “progress” which Paglen and others keep warning us about.

No, we do not know of any real aliens or their motives yet, but for METI which are attached to spacecraft that have no long-range goals other than to drift aimlessly through space, we can define the parameters for the kinds of intelligences that will be required to find these vessels and their messages. For both the EchoStar XVI Artifact and the two Voyager Records, our ETI will need to be capable of sophisticated interstellar travel, which means knowing some form of science and technology, which includes mathematics. All that will come from a species which not only has high knowledge but actively seeks it out. This much we can reasonably guess about our recipient intelligences. Whether they do or will actually exist, of course, remains to be seen.

In fact the odds of a properly equipped ETI or future humanity finding the Artifact are much higher than for the Voyager or Pioneer probes, since EchoStar XVI will remain circling its home planet along with many other satellites for ages, while our first craft to venture into the interstellar void are few in number and will drift through galactic parts unknown beyond a light year or two, with no power and not even enough starlight to expose their existence by reflection. Anyone deliberately visiting our Sol system for the purpose of investigation should find it hard to ignore Earth, a shiny rock almost eight thousand miles across, whatever state its surface may be in. The same should then follow for the thousands of glittering metal objects surrounding it like a halo.

The Fate of the EchoStar XVI Artifact

In the “Epilogue: Deep Futures” chapter of The Last Pictures, Paglen discusses the ultimate destiny for the comsat and its unique passenger. He wonders if EchoStar XVI and the Artifact will survive all sorts of potential mishaps way out there in space, including the day when our sun becomes a red giant that could consume Earth and its artificial ring of satellites. Paglen imagines EchoStar XVI surviving not only that phase of our star’s existence but also its subsequent white dwarf stage several billion years later.

Untouched by either human or alien appendages during all these eons, the artist’s vision for his creation eventually reaches into the very remote future:

“In a hundred trillion years, star formation will begin to cease throughout the Universe. One by one, the points of light that dot the Cosmos will go black until they are all gone. By this time a wayward neutron star or pulsar will have come perilously close to what was once the sun, sending a great wave through spacetime, spinning EchoStar XVI and The Last Pictures off into never-ending darkness.”

Paglen’s interpretation for his work is epic, ominous, poetic, even romantic in a sense, to be sure. But just how realistic is it? Of course there is no way to know exactly what will happen to EchoStar XVI and the Artifact even in the next few centuries; however, we can make some educated guesses. Understanding what might happen to the comsat and its cargo will also help us to determine the fate of all the other spacecraft and their accompanying rocket stages and other debris drifting about our Sol system and beyond.

If left alone by humanity as Paglen sees the relatively immediate destiny of The Last Pictures (he does not hold out much hope for our species conquering the stars or even much closer to the world of our birth), EchoStar XVI could last for many millions of years in supersynchronous orbit. As stated earlier in this piece, the satellite will very likely be battered by meteoroids, solar flares, and cosmic rays. The bulk of this by-then dead relic and the Artifact cover should protect those one hundred small photographs through all but the worst of those celestial possibilities. It must be recalled that even in the relative vicinity of Earth, space is still wide open and in a vacuum state more pure than anything we can yet replicate. So barring an accidental or deliberate collision, the Artifact may indeed last at least through the final days of our sun’s yellow dwarf stage.

There is also a more than fair chance that Paglen could be wrong about humans creating a permanent presence in space. In as little as one century from now, orbital debris cleaners, scrap metal prospectors, and space archaeologists could be rummaging about in those special high Earth orbits in their respective efforts to make a safe path for new satellites, increase their wealth, or add one more piece of knowledge to the database of information about the first decades of the Space Age.

In the first two scenarios, The Last Pictures might become lost or destroyed, the finders possibly either failing to recognize the golden disk bolted to the side of EchoStar XVI as a message for them or simply lacking the interest to delve into the object. For the space archaeologist of the not too distant future, however, this discovery would not only be treasured but still largely understood, assuming the companion book and other records about those one hundred photographs and how they got into orbit remain accessible. Of course the first two cases could just as plausibly grasp and appreciate the Artifact for what it is, even if only interpreting it as a monetary bonus at the behest of some eager historian or archaeologist.

While I can see EchoStar XVI and The Last Pictures making it through many millions of years in space intact if not unscarred if left alone, I have my doubts they will survive even before our yellow dwarf star goes big and red. At least several scenarios which Paglen did not address, as far as I can find, that could easily take out a comparatively little communications satellite and its even smaller golden disc include as follows:

Earth and the rest of the Sol system being turned into a Dyson Shell. Or if not an actual Dyson Shell as envisioned in several current scenarios, then something similar to this major astroengineering project. I can envision EchoStar XVI and its brethren end either as part of the construction material or ignored altogether and lost or destroyed in the building process.

While there are those who say that Dyson Shells will never be built for a variety of reasons, one cannot now argue with the fact that roughly one billion years before Sol becomes a red giant sun, our Milky Way galaxy will be merging with its neighboring spiral stellar island, Andromeda. Astronomers say the odds of a collision between the suns of these two galaxies are quite slim, but they also say that whatever is left of the Sol system could be flung further out or even ejected into intergalactic space, affecting everything else floating our celestial neighborhood to an unknown degree. In addition, long before this event our Sol system will have more than a few close encounters with other stars in its own galaxy, which could disrupt any one of its circling worlds, including Earth and its retinue of satellites.

Speaking of satellites, Earth’s one very large natural satellite, the Moon, could one day greatly affect anything still existing in geosynchronous orbit. While currently the Moon is slowly drifting away from us, eventually tidal interactions between the two worlds will cause this to stop and slowly bring the Moon back towards Earth. Should these globes survive the solar red giant stage, the Moon will find itself torn apart by tidal forces at the Roche Limit located 11,470 miles above Earth’s surface. A huge ring of debris which was once our natural satellite will form, spreading its countless fragments all over the cislunar space. These rocky chunks would smash any artificial satellites that somehow managed to survive every other potential catastrophe. The fascinating details on this scenario may be read here.

As exciting and romantically appealing as it may be that EchoStar XVI and its Artifact will somehow outlast the vagaries of the Universe into endless time, I find it hard to fathom that either object will make it to the red giant Sol era even if no human or large natural event ever touch the comsat before that time. However, I think it is a valuable exercise to better estimate just how long the EchoStar XVI Artifact really could survive in a recognizable state. For those who want to preserve our knowledge and history (and therefore ourselves) for future beings and send messages to those remote eras, knowing how to do so is more than just an intellectual exercise or thought experiment. It will also make The Last Pictures more than “just” a contemporary art project.

Final Thoughts

While researching back and forth between the two primary books on the EchoStar XVI Artifact and the Voyager Interstellar Records, The Last Pictures and Murmurs from Earth, respectively, I began to realize something the two projects had in common – perhaps the most subtle and meaningful message conceived by Paglen and his production team.

Although the Voyager Record was primarily meant as a scientific message to the ETI who find the probes – the book Murmurs discusses repeatedly how most every photograph was chosen to pack in as much information about us and our world as possible – this very detail begins to blur as one looks at the images, especially those depicting people. The same goes for The Last Pictures: Though they were meant to be artistic and carry social messages first, their science value in terms of relaying important information about us as biological creatures becomes obvious after a time. The Voyager Record team assumes a lot of understanding by the recipients, for they assume the investigators will be scientists or at least very scientifically curious. While this is certainly a possibility, there is also no guarantee. My musings had me wondering if science is just as subjective as Dr. Nunez says mathematics is?

The example from the Voyager Interstellar Record that first struck this thought in me is not the image of “licking, eating, and drinking” as one might imagine, but one showing a man standing atop a rock spire in the Alps. As the book caption says about this photograph: “If the recipients recognize the silhouetted human figure, they may guess that it was both difficult and seemingly pointless to scale this rock needle. The only point would be the accomplishment of doing it. If this message is communicated, it will tell extraterrestrials something very important about us.”

Image: French climber Gaston Rebuffat in the Alps in this image from the Voyager ‘Golden Record.’

In Paglen’s art collection, there are two images involving an individual and an ocean. In one, waves are splashing against a standing woman with her back to the water. The other photograph shows a man surfing a huge curling wave of water. Both of these depictions could also be interpreted as humanity performing acts that are “difficult and seemingly pointless,” other than “the accomplishment of doing it.” Other scenes with large crowds of people and vehicles tended to magnify that blending and merging effect for me.

Both METI efforts also have numerous depictions of animals, with several showing different creatures interacting with various humans. The Voyager Record team chose their human-animal interaction images to depict how we use animals as companions, objects of scientific study, to help us accomplish tasks, and for food. Paglen’s animals are there mainly to show how often cruel and neglectful the members of his species are to the other residents of Earth.

While The Last Pictures does show an image of many rows of chickens in cages and a bizarre bit of art about a piano which uses cats for the musical notes, other images appear rather benign: A shark swimming in a huge aquarium tank, a child looking at an orca in a large swimming pool, and some longhorn cattle standing passively in a field. By contrast, I found some of the Voyager Record parallels capable of being interpreted as animal cruelty, though that was not their original intent: A human riding an elephant which is lifting tree logs with its trunk; a scientist measuring an alligator that is lying on its back (and appears to be dead); fishermen capturing large quantities of fish in their nets (there is a very similar photograph in The Last Pictures); a man frying fish on a grill. How will an ETI interpret these images, especially if they happen to resemble some of the animals depicted, or know fellow beings similar to them.

The feelings I had as I looked back and forth between the two collections are perhaps summed up by Katie Detwiler, an anthropology student who worked with The Last Pictures research team, who relayed the following in this quoted section from the aforementioned article on the project in The Atlantic:

“Such images don’t explain themselves; in some cases, they impart next to nothing without supplemental texts. Paglen insists that’s partly the point, an intent he made clear to his research assistants. “He was interested in images that were unstable or undermined their own truth claims,” said Katie Detwiler, and anthropology student at the New School, in New York, who was part of the research team. “Sometimes in my own search for images, it became really difficult to commit to any image over another,” she added. In deep time, it wasn’t “possible to communicate any meaning,” she said. “It could be a picture of a flower or a picture of a slaving ship. There’s no distinction at the endpoint that we’re thinking of.”

I was reminded of the time I visited an art museum and found the beautifully polished wooden floor I was walking upon just as much a work of art and craftsmanship as any of the painting on the walls that were supposed to be the main reason I was at the museum in the first place. Was I wrong to find the straight lines and pleasant coloring of the wood planks beneath my feet just as impressive as the paintings hung just a few feet above them? This was not even a negative comment on the wall art, for they too were impressive in their art and craftsmanship. As I further recall, the whole building which housed both the paintings and the floor could be called a work of art, too.

So how will the recipients of the far future interpret the contents of the EchoStar XVI Artifact and the Voyager Records? Will they understand even a bit of what they are looking at, if they can look at the images in the same way we do at all? Having come a very long way in a sophisticated starship (we presume), will they focus their attentions on the spacecraft and find the information packages “seemingly pointless” as a Voyager Record team member said about the rock climber?

Image: The mission poster for EchoStar XVI. Credit: Space Systems Loral/International Launch Services.

As Trevor Paglen replied when confronted by Dr. Nunez about putting scientific messages on the Artifact cover to assist the recipients in interpretation, perhaps all that can be done here is to do it whether the odds of understanding the artifacts are good or not: Nothing is lost if they are meaningless, but they become a major benefit to the finders if they can aid in understanding who built these ancient vessels and sent them into deep space and time.

To add a final point (for now), I came across a review of The Last Pictures in my later researches for this piece which really caught my attention. Many reviews of Paglen’s work were brief rehashes of what his project was about, or they betrayed how little the author understood both the significance of the art itself and the science behind it all (bemusement at the idea of aliens finding the satellite and its golden container with the images was a particular trend). They also tended to show the same select group of photographs repeatedly.

This particular review by Rob Sullivan of the Department of Geology at UCLA took Paglen to task on numerous levels, from his perceived hubris for calling them The Last Pictures (but would anything other than a dramatic, ultimate gesture have sold the project in the first place?) to his assumption that satellites in space would make great places to preserve items for a very long time.

Among Sullivan’s complaints were ones which have been echoed upon the makers of virtually every METI effort where a small and select number of people were involved, as quoted here:

“For reasons that never seem to have warranted one moment of self-reflection, Paglen relies only on collaborators whose resumes would qualify them as the elite of the elite of America’s Creative Class. Paglen litters the book with references to well-known academics, as if the inclusion of such worthies would guarantee the probity of the project. And so a question of class and status arises. Why should cognitive scientists teaching at UC San Diego and curators from MIT’s List Visual Arts Center have access to the decision-making process of this project but not waitresses and truck drivers, let alone poets, painters, and filmmakers? This may sound like a facetious protest, but if this project is to be a record of all humanity intended for the ages, what exactly is the criterion for inclusion within its selectors? Is it only the highly educated who are allowed on board? Does one’s resume have to bulge with advanced degrees in order to have an opinion about the meaning of the planet and, therefore, the contents of its archive? There’s a miscarriage of democracy here, especially if the disc containing the archive actually does become the record of the present to the future.”

While I agree with Sullivan’s complaint on one level, that if we are sending something out into deep space and time which represents the human species, then many people should have the chance to be part of that depiction of their own kind, there is something else to consider: Most METI projects, including and especially the Voyager Records, might never have happened at all without the efforts of a few key people. Sagan and his team tried hard to be international and multicultural in scope (look here for a bit of commentary by someone who felt that making the Voyager Record contents so “politically correct” and inclusive took away from their effectiveness – plus he also found them to be pessimistic in the sense that the creators seemed to be acting as if the human race might vanish shortly after their launch into space!), but they also had be the ultimate, final say on items for the Record, at the risk of having the whole project vanish by a disapproving NASA. If I may go so far in saying so, if the Voyager probes had left Earth in 1977 without those LP records attached to their sides, it would be as if they were lacking a soul, in a sense. At the very least a representation of the human essence which you may call a soul or whatever else you like.

When the New Horizons probe was being readied to become the first mission to flyby Pluto in 2015 (and only the fifth spacecraft to eventually leave the Sol system), that space vessel team purposely opted not to attach any kind of information package of the same significance of the Voyager Records or even the Pioneer Plaques. Instead they opted to treat the situation as if they were putting together a time capsule that some small town might bury in their local park for one hundred years.

Other than including some of the ashes of Clyde Tombaugh, the astronomer who discovered Pluto in 1930, every other item placed on New Horizons was meant merely as a memento to the team, with no effort to make them comprehensible to future beings who might find the probe one day drifting far beyond our Sol system. This is what happens when not even a small group of people are allowed to make an effort to share something about ourselves on deep space missions.

For the details on what is riding out to Pluto and beyond and the rather sad story of how things came about, look here.

Despite the warnings above, we should have more METI projects which include large swaths of people from across the planet. They do not to be as elaborate as Paglen’s effort and with private space businesses coming into their own, they should be able to happen on a more regular basis. Add the modern technology to store lots of information on a readable media and you can tell quite a lot about our species and our world.

Besides, if someone is unhappy with Paglen’s vision of humanity and how he expressed it, then by all means they should create their own expressions. Imagine not one last collection of pictures but thousands of works of art, messages, and information spread throughout space. Here would be a true democracy of ideas and representations, long-lasting monuments to our species at the shores of the cosmic ocean, as Carl Sagan would have said.

I really do believe these efforts have the ability to make people more aware of the wider Universe they live in and better appreciate how important it is to live for more than just today. If we expect to start venturing to the stars in earnest in the next century or so, we need future generations who will look past the planet of their birth to the vast galaxy of star systems beyond and the mere decades of existence given to an individual human and recognize the possibilities of living on for ages through the next generations.

For a video by The Last Pictures team about their project, visit here.

A final word from Carl Sagan in the Epilogue to Murmurs of Earth, appropriate to all messages sent by humanity into the void:

“But one thing would be clear about us: No one sends a message on such a journey, to other worlds and beings, without a positive passion for the future. For all the possible vagaries of the message, they could be sure that we were a species endowed with hope and perseverance, at least a little intelligence, substantial generosity and a palpable zest to make contact with the cosmos.”

What can i say! beautiful and deep musings!

I can tell the author’s feelings run deep on this subject; of the human race being temporary.

I prefer to think of us as the salmon that makes it all the way upstream. Not that we have any evidence of any other civilizations surviving for very long. Our pride is what informs us that we are unique in the universe and this hubris causes us to doubt the rise and fall of other civilizations.

There is no doubt in my mind; the numbers are coming in and they say there are many earth’s, but no tv shows.

We are an endangered species- as endangered as each individual. That means we are doomed. I doubt we fit into the category of a truly intelligent species; we do not cooperate to safeguard our species collectively or individually.

Aliens might consider us in a lower class of cognitive ability.

Sorry, I find this a rather depressing post. A comment such as: “It is a collection of images that explained to somebody in the future what happened to all of the people who build the dead spaceships in orbit around the Earth. And how they killed themselves.” don’t seem to contribute anything positive (not to mention its wobbly verb tenses). Perhaps Paglen would like to explain to me in the present who exactly is supposed to have killed themselves — this sounds like a burst of pessimism from the depths of the Cold War in the 1970s. I think an artist and geographer would be better employed portraying for the benefit of people currently alive how best to consolidate our civilisation for its long-term survival and growth.

I am currently reading a book by another geographer, “Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive” by Jared Diamond. His project in this book is to analyse how past societies survived or collapsed, so that we in the here and now can put that knowledge to good use, and this is both fascinating and of great practical value.

Stephen

A rather sad and depressing piece. Are we really doomed then? Are these “last pictures” a gesture of our throwing up our hands at the futility of it all?

Intelligence has the responsibility to survive. Indeed, that’s what its for, don’t you know. But in order to do this we will need to know the difference between right and wrong, because if we extinct ourselves it will be because we never learned the difference, or even realized that there is a right and wrong. Scientists perhaps more than anyone need to come to a realization of this, a notion sadly bereft among them, and even more so among those who fund and exploit their efforts.

Wow, this post will make an excellent weekend read. I am a newbie in this area, but so interested. I m a professional from a different background and would like to thank the author for a quality post and site and spending so much time helping people like me think at a deeper level.

Shad

For those who are interesting in knowing what the EchoStar XVI Artifact mission patch says around its borders, my Ukrainian friend Lyudmilla Shcherbanyuk translated it for me as follows: