Not long ago, Ramses Ramirez (Earth-Life Science Institute, Tokyo) described his latest work on habitable zones to Centauri Dreams readers. Our own Alex Tolley (University of California) now focuses on Dr. Ramirez’ quest for ‘a more comprehensive habitable zone,’ examining classical notions of worlds that could support life, how they have changed over time, and how we can broaden current models. We can see ways, for example, to extend the range of habitable zones at both their outer and inner edges. A look at our assumptions and the dangers implicit in the term ‘Earth-like’ should give us caution as we interpret the new exoplanet detections coming soon through space- and ground-based instruments.

by Alex Tolley

The Plains of Tartarus – Bruce Pennington

In 1993, before we had detected any exoplanets, James Kasting, Daniel Whitmire, and Ray Reynolds published a modeled estimate of the habitable zone in our solar system [1]. They stated:

“A one-dimensional climate model is used to estimate the width of the habitable zone (HZ) around our sun and around other main sequence stars. Our basic premise is that we are dealing with Earth-like planets with CO2/H2O/N2 atmospheres and that habitability requires the presence of liquid water on the planet’s surface. The inner edge of the HZ is determined in our model by the loss of water via photolysis and hydrogen escape. The outer edge of the HZ is determined by the formation of CO2 clouds, which cool a planet’s surface by increasing its albedo and by lowering the convective lapse rate. Conservative estimates for these distances in our own Solar System are 0.95 and 1.37 AU, respectively; the actual width of the present HZ could be much greater. Between these two limits, climate stability is ensured by a feedback mechanism in which atmospheric CO2 concentrations vary inversely with planetary surface temperature. The width of the HZ is slightly greater for planets that are larger than Earth and for planets which have higher N2 partial pressures. The HZ evolves outward in time because the Sun increases in luminosity as it ages. A conservative estimate for the width of the 4.6-Gyr continuously habitable zone (CHZ) is 0.95 to 1.15 AU.”

Climate models have improved considerably over time, and now are capable of three dimensional (3-D) models as well as more advanced 1-D models. Parameter estimations are also being refined to account for different atmospheric features.

The 1993 Kasting et al paper set the bounds for a conservative HZ at 0.95 and 1.37 AU, the outer bound being inside the orbit of Mars. However, the authors noted that a maximal greenhouse with a dense, CO2 atmosphere would push the outer bound to 1.67 AU, that would include Mars, although this was considered optimistic. In 2013, Kopparapu, Ramirez, Kasting, et al, published new estimates on the HZs using a more advanced 1-D model [3]. For the Solar System, the inner and outer edges were 0.99 and 1.67 AU respectively, with the now conservative outer limit at maximal greenhouse warming.

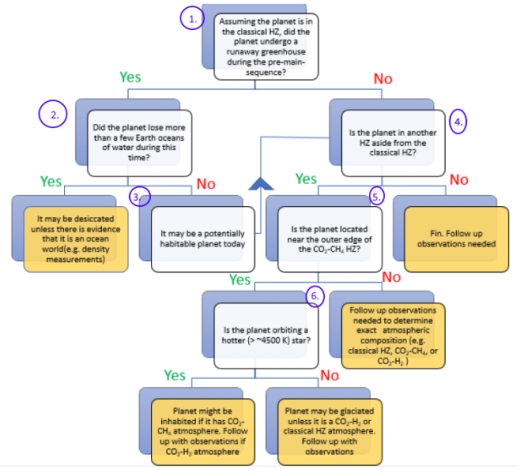

In 2018, Dr. Ramirez published a review of HZ research that included ideas that extended the HZ in time and space, as well as a wider range of stellar types [4]. The conclusion of that paper included the decision tree concerning newly discovered planets and models of their environments. The decisions have identifying numbers added and are shown in figure 1.

In a recent Centauri Dreams essay, Revising the Classical ‘Habitable Zone’, Dr. Ramirez outlined his reasons for studying models of planetary habitable zones (HZ) and environments as part of the search for life. This post will try to tie the many ideas of the journal article to the decision points in figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Reproduced from the paper [4], annotated with numbers.

1. Assuming the planet is in the classic HZ, did planet have a runaway GHE during pre-main sequence?

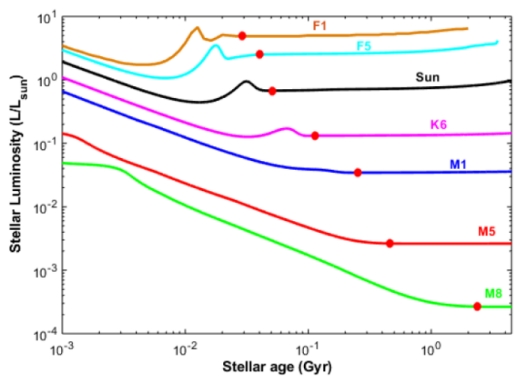

The classic HZ calculates its inner limit as the point at which a runaway greenhouse effect (RGE) can occur. This inner edge is calculated for the period when the star is in the main sequence. For most stars, the main sequence starts quite quickly, within 0.1 Gyr of the nebula forming, allowing life to evolve after the main sequence had started and before the star in its potentially more luminous pre-main sequence state has had time to initiate the RGE. However, for the numerically numerous M-dwarfs, this pre-main sequence period may last for up to a 1 Gyr and have orders of magnitude more luminosity than during the main-sequence. Any planet currently in the classic HZ would have been subject to far higher luminosities and with a time period sufficient to desiccate the planet. The world might then be like Venus, a hot, dry world, with our without a dense CO2 atmosphere. Transit techniques will detect Earth-sized rocky worlds more easily around M-dwarfs, which have attracted a fair amount of discussion about the conditions for life on their surfaces. The issue of a high luminosity during a long pre-main sequence period may trump any favorable conditions during the current main sequence period. Therefore whether the exoplanet lost all of its water during this time needs to be addressed, which leads us to:

Figure 2. Evolution of stellar luminosity for F – M stars (F1, F5, Sun, K6, M1, M5, and M8) using Barrafe et al. [184] stellar evolutionary models. When the star reaches the main-sequence (red points) the luminosity curve flattens. [4]

2. Did the planet lose more than a few Earth oceans of water during the pre-main sequence period?

An Earth analog planet will desiccate like Venus if it loses more than a few Earth oceans of water. It is possible that the water loss was not severe when the planet entered the classic HZ. If the water loss was high, the world would be desiccated, like Venus.

If any of these conditions are not satisfied:

3. If water loss was not sufficient to desiccate the planet

If the period and intensity of water loss was insufficient to result in a complete RGE, or the starting volume of water was low, then the planet may be characterized as a desert world, with lakes of water, possibly at altitude.

One possibility is that the world is an ocean world with far higher quantities of water than an Earth analog. In this case, desiccation has been held off as a result. Density calculations for that world will indicate if the planet may be an ocean world. As far as life is concerned, we would return to the issue of whether such ocean worlds are suitable for sustaining any abiogenesis derived life.

If the planet has retained enough water it may join the candidates for the next decision: This allows the planet to be considered potentially habitable regardless of early heating.

The author then allows for a wider interpretation of the HZ:

4. Is the planet in another HZ that is outside the classic HZ?

The bulk of the paper deals with possible modifications of the HZ that extend its range at both the inner and outer edges. The paper documents a number of mechanisms that could widen the HZ and to what one might call an optimistic HZ.

Some examples are listed below:

A. Empirical vs model HZs

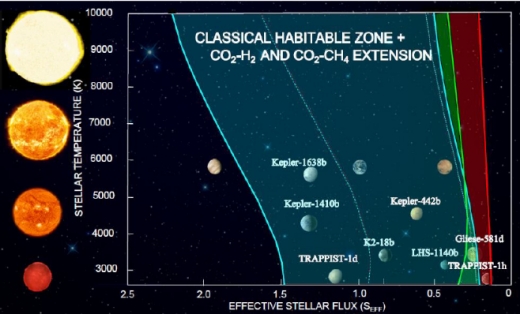

The author argues that empirical, rather than model limits for the classic HZ might be applied. These limits imply that the outer edge must have been further than the climate model as Mars has evidence that it once had running water on its surface when the sun’s luminosity was lower. For the inner edge, this puts the edge of the HZ closer to the sun at 0.75 AU, but still outside the orbit of Venus as the planet has no sign of surface water even 1 Gya when the sun was cooler [Figure 3].

B. Stellar spectral range

The author argues that the apparent rapid emergence of life on earth allows for hotter, shorter-lived stars to harbor life before they exit the main sequence. This extends the HZ to beyond the star types usually associated with life, but to large, hot stars.

C. Extensions of the HZ in space

Greenhouse gases like methane (CH4) and hydrogen (H2) can extend the HZ, particularly at the outer edge. Methane could extend the HZ beyond Mars, and as it is also produced biologically in greater quantities than geological processes, can maintain the gas in the atmosphere. It is often cited as a detectable gas out of equilibrium and possibly indicative of life. H2 may also contribute to warming and has be posited as a possible explanation for the warmer, ice-free Earth during the Archean.

Ocean worlds are often cited as having unregulatable temperatures due to the absence of exposed crust that prevent the carbon-silicate cycle to act as a carbon sink. One model of ocean worlds with ice caps suggests a way for this sink to operate with CO2 clathrates.

Binary stars would appear to be problematic for worlds to stay in their HZ. The climates are difficult to model, especially where the planet orbits one star, but the planet may create a temporary, benign temperature with periods of freezing as is transits into and out of an HZ.

3-D climate modeling is now increasingly able to compute the effects of rotation rates and different types of cloud cover and composition. The results vary regarding whether these parameters can extend the HZ.

This leads to a sub-question: about the outer edge of the extended HZ:

5. Is the planet near the outer edge of the classic HZ?

The classic HZ outer edge is set by the maximum warming effect of an atmosphere with CO2 and H2O. However, there are some possible ways to extend that outer edge using other greenhouse gases like CH4 and H2. Figure 3 shows the effect of CH4 and H2 on the outer limit of the HZ. For most worlds, retaining a light H2 component to the atmosphere is unlikely, unless it is maintained by some geologic or biotic process. Other possibilities include transient warming periods, possibly even limit cycles that create warm conditions on a periodic basis, perhaps with CH4 or H2 that can exist for short periods. Of course, life would have to survive in some form during the planet’s frozen period. Even on the hypothesized Snowball Earth, liquid water was probably present below the surface ice. For a solidly frozen world, the conditions for survival would be harsher.

For M dwarfs, with high luminosity, and long pre-main sequence periods, planets currently residing at the outer edge of the classic HZ may have been habitable during this pre-main sequence period. Life may have evolved during that period, then retreated to the subsurface as the planet cooled. This is analogous to the hopes of some that life on Mars may have evolved when the planet had surface water, but may still exist at depth as Mars surface cooled and dried.

Figure 3. The classical HZ (blue) with CO2-CH4 (green) and CO2-H2 (red) extensions for stars of stellar temperatures between 2,600 and 10,000 K (A – M-stars). Some solar system planets and exoplanets are also shown. [4]

6. Is the planet orbiting a hotter ( >~ 4500 K) star?

Because the star type influences the warming of the atmosphere and planet’s surface, only stars with a surface temperature greater than 4500K will extend the outer edge of the HZ with the greenhouse gas, Ch4, as part of a dense CO2 atmosphere. Unintuitively, for cooler stars, CH4 in the CO2 atmosphere brings the outer limit of the HZ closer to the star. This is clearly shown in Figure 3. [See also CD post The Habitable Zone: The Impact of Methane.] Hydrogen (H2) will quite considerably extend the outer limit of the HZ for all stellar types. Spectroscopy to determine the atmospheric mixing ratios will help in determining whether this is possibly the case.

Other considerations

The paper ignores the current vogue for life in icy moon subsurface oceans for good reason as any subsurface liquid ocean is undetectable by any telescopes that we have on the near horizon. Focusing on the HZ where surface water can exist makes operational sense.

This paper does us a service in not just offering routes to expanding the HZ, but also in the approach to characterizing planets, and ultimately to modeling them accurately once we have the empirical data to support these models.

In passing, the author gives credence to the issues of interpreting results. There is a criticism of the use of “HZ” and “Earth-like” and super-Earth” to imply that those exoplanets have Earth-like life in abundance on their surfaces. In many ways, the extending of HZs retains the concept of surface water possibly existing. In the original Kasting et al paper, their HZ definition required surface water as a necessary condition for life to evolve, as we currently believe. Nevertheless, these worlds may be sterile, as this condition may be insufficient.

As Moore states[5]:

“Habitable planets, not habitable zones Similarly, the term habitable zone is misleading to both the public and the scientific community. On the face of it, habitable-zone planets should be, well, habitable, but in its now classic definition, this is the region in which the presence of a liquid water surface “is not impossible” with an atmosphere assumed to be Earth-like. It does not mean that a habitable zone planet would, in fact, have a wet surface or any other condition required for life. Furthermore, this definition ignores the potential for deep, chemosynthetic biospheres and biases our thinking toward only one of the many ways in which life manages to sustain itself on Earth. That the term habitable zone has such a disconnect with the concept of habitability is problematic for communicating ideas clearly and yet its use has become entrenched in discussions of new exoplanet results and it continues to inform the design of our exoplanet program.”

For life in the Earth’s Archean eon, prokaryotic methanogens create methane (CH4). This greenhouse gas must be present in sufficient quantities to be detected and should push out the inner bound of the HZ.

With these caveats in mind, the Ramirez paper suggests that we can use these expanded HZs to both focus the search for targets, and to validate the models so that targets can be more accurately determined as we extend our searches. This might be very timely as the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) all-sky survey is already turning up many potential targets.

References

Kasting, J.; Whitmire, D.; Raynolds, R. “Habitable Zones Around Main Sequence Stars.” Icarus 1993, 101, 108-128.

Kasting, J. How to Find a Habitable Planet. Princeton University Press, 2010.

Kopparapu, R. K.; Ramirez, R.; Kasting, J. F.; Eymet, V.; Robinson, T. D.; Mahadevan, S.; Terrien, R. C.; Domagal-Goldman, S.; Meadows, V.; Deshpande, R. “Habitable Zones Around Main-Sequence Stars: New Estimates.” Astrophys. J. 2013, 765, 131, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/765/2/131.

Ramirez, R M “A more comprehensive habitable zone for finding life on other planets” Geosciences 2018, 8(8), 280.

Moore et al “How habitable zones and super-Earths lead us astray” Nature Astronomy volume 1, Article number: 0043 (2017).

H2 or molecular hydrogen is not a greenhouse gas since it does not absorb in the blackbody, thermal, infrared spectrum. Molecular hydrogen comes from CH4 oxidation and H2 also reduces the OH levels which makes the CH4 have a longer life. H2 only indirectly contributes to greenhouse warming.

I agree that the life belt or habitable zone does not provide enough information to know whether a planet has water or even life on it. One needs to know the size and mass of the planet which affects how much atmosphere it can hold or have liquid water on its surface. Also the carbon cycle depends on healthy volcanism, on plate tectonics a solid, moving crust. and the size of the planets core; Mars core cooled off too quickly and it’s crust is too thick for plate tectonics.

There is the need for a magnetic field and a Moon to deflect the solar wind and atmospheric stripping to keep an atmosphere over a long time. We will see what the James Webb space telescope and telescopes of the future can do with exoplanet spectroscopy.

Interesting point about how H2 contributes to warming.

This paper explains it in more detail for a hypothesized paleo-Earth model.

H2 not absorbing stellar energy neither means it’s not greenhouse gas nor it only contributes indirectly by extend the lifetime of CH4.

Collision-induced absorption resulted from H2–H2 collisions allows strong greenhouse effect out to great distance due the low condensation point. A thick *pure* hydrogen atmosphere (tens of bars) can keep the temperature of the surface of a planet above freezing-point in interstellar space.

See Pierrehumbert, R., & Gaidos, E. 2011, ApJL, 734, L13

So we need a third axis for planetary mass in addition to stellar temperature and flux to define a planetary zone, as if Mars had been Earth-sized it would undoubtedly look very different.

Why is a moon necessary to deflect solar wind and atmospheric stripping? Venus doesn’t have one or even an intrinsic magnetic field, but it’s definitely got an atmosphere.

Yes, the only reason a moon seems required for life is to create stable seasons. Stable seasons might only be required for our kind of life, simple life can probably handle way more erratic climate changes then we experience at earth.

I guess more than anything we need solid data for as many planets as possible. Then compare the data to the models. They may be extremely biased and not that useful in the long run, or they may be surprisingly accurate. This is clearly an extremely long term project. First we continue to identify targets, then we have to get spectral data from planetary atmospheres to find evidence of water and greenhouse gases. In addition it would be useful to see the surface of these planets telescopically and determine the ratio of solid and liquid regions. If we can get data for a statistically significant number of planets (I’m not sure how big the minimum sample size would need to be) then we might be able to either throw out the models or modify them or be amazed at how accurate they are.

For the nearer exoplanets, I wonder if a telescope or flyby probe will be the first to do this, even crudely. We saw the impressive results of the New Horizon’s Pluto-Charon flyby compared to the best images from the Hubble telescope that we had prior to that event. The first flyby images of an exoplanet should be similarly breathtaking.

Sure it will be if you are talking about land-ocean distribution, even continental configuration.

If LUVOIR or other sorts of 8-m class space telescope (SUPERSHARP) is selected, vague continents and oceans could be mapped longitudinally over the rotation period of the planet within 30 light years.

Finer details like continental configuration, forests, mountains and gigantic stromatolite architectures might be achieved by large space interferometer mission, something like 30 Hubble-sized space telescopes. Hopefully, this interferometer would become possible by the end of this century.

Great summary of the issues, Alex Tolley!

“Life” in the sense of an “array of biological phenomena” would be an extension of physics & chemistry; many essential intervening stages may have been developed and then discarded, making it difficult if not well-nigh impossible to trace it back.

The progression from prokaryotes to philosophers as we are privileged to recognize it, might have been arrested at any point in time and may indeed have occurred elsewhere and elsewhen in the Cosmos.

The real reason to look for vats of “life” lies in the possibility of that progression. Yet that progression could also be halted and discarded with a phase change from biological to post-biological intelligence.

The time-frames in which each phase may exist in deep time are unknown. It is possible that post-biological intelligence may have a vastly greater presence in astronomical time and space with such little disruption of matter and energy as to be almost imperceptible.

Looking for “life” is a part of the deeper quest for the actions and artifacts of intelligence.

SETI may well eventually find a signal, but it will prove post-biological. There are so many options for this, from uploaded minds to machines or world-sized computational substrates, minds free of physical form, AIs, etc. These forms may have civilizational lifetimes as unknowable as biologically based ones.

Your point about a low disruption of matter and energy is one of the Fermi Question answers, and arguably the eventual state of the monolith builders in Clarke’s Odyssey tetrology.

Could dark matter and dark energy be part of the infrastructure of a Cosmos-wide intelligence?

Wouldn’t it be ironic if dark energy was a pollutant from a number of KIII or a single KIV civilization?

Thanks for a nicely succinct post.

We live both an exciting but simultaneously frustrating time? More and more exoplanets discovered near daily ,with literally tens of thousands more to come in the next decade or so – but hardly any atmospheric classification. What little there is covers “Hot Jupiters” too , far from the temperate planets largely cited here in this decision tree. The modelling represents excellent work , the best available indeed , but is still only modelling and as we know this has repeatedly been shown to be flawed from past experience as observational data became available. The very existence of the Hot Jupiters a themselves a classic case in point. We are treading water and must continue to recognise that until JWST and/or the E-ELT finally cover the Trappist-1 or some other proximate M dwarf planet.

As Sherlock Holmes said “we need more data . Without data facts are made to fit theories rather than theories to fit facts ” .

I think the work of Sara Seager (MIT) is important in the field of spectroscopic life detection, biosignatures, and exoplanet habitability. For instance she has compiled a list of molecules that may indicate the presence of life.

Very interesting article yet again Paul. This field will explode in the coming decades as our detection abilities get better and better.

*ahem*

I was thinking of 51 Pegasi b, discovered in 1995. Perhaps I should have said”…around a main sequence star”. But you are correct, an exoplanet had been discovered by 1993.

It’s interesting how the exoplanet field managed to forget about the pulsar planets, there are a lot of papers out there that appear to assume that 51 Pegasi b was the first exoplanet. In particular, you see mentions of the pulsar planets start disappearing during the time that RV detections were pushing down to ever-lower masses: while the discovery paper for Gliese 876 d correctly notes that the PSR B1257+12 system contains lower mass planets than Gliese 876 d (although there is a typo in the pulsar designation), by the time Gliese 581 c comes along people seem to be perfectly fine stating that a 5 Earth mass planet as the lowest mass found for an exoplanet. The discovery paper for the sub-Mercury planet Kepler-37b claims that “no prior planets have been found that are smaller than those we see in our own Solar System” – the ~moon-mass inner planet of PSR B1257+12 was discovered in 1994.

Thanks to Alex Tolley, very thought provoking article!

One way that could give an indication of a large scale civilizations would be similar planetary atmospheres in multi-planet systems. We are already planning on terraforming Mars and Venus so that would be a good indicator in systems like Trappist 1.

https://amp.space.com/41714-water-rich-exoplanets-trappist-1-system.html

Looking at nearby stellar planetary systems close to systems like Trappist 1 could also be an indicator of such civilizations having interstellar travel.

http://www.science20.com/jose_solorzano/multistellar_seti_candidate_selection_kaggle_kernels-234091

A very large telescope on the dark side of the moon just seems like an absolute must. A base there makes maintenance much easier than that required for a deep space telescope doesn’t it? We need to extend our reach as far as manned exploration goes. The moon is certainly an obvious place to start and construction of a large telescope gives us an obvious reason to go back there.

Nicky. In planetary atmospheric science it is commonly accepted that any gas no matter what its molecular weight will become a greenhouse gas if the atmosphere is thick enough such as ten bars or ten times Earth’s pressure at sea level. There aren’t any Earth like planets with ten bars of pressure since we wouldn’t consider them to be Earthlike.

Also what determines a greenhouse gas is based on quantum mechanics; Co2, CH4, No2(nitrous oxide), etc. all absorb EMR only in the infrared spectrum. All other EMR, gamma rays, x rays, ultra violet visible light, and radiowaves pass right through these molecules but not the infrared which is absorbed. The absorption causes these molecules to vibrate and rotate which is the same thing as heat. This vibration heats the other gases and air of the planet and keeps it warm. The glass in the greenhouse or car lets the sunlight through but the invisible infrared radiation can’t escape. A similar effect happens on the surface of a planet, the atmosphere is transparent to visible light but the greenhouse gas is opaque to the infrared and traps the heat

To get technical the electron cloud in every atom and molecule has a ground state, the lowest energy state or rest state which is between zero and one. The distance from zero to the first energy level in the electron is equal to a specific wavelength or frequency, so every atom and molecule will only absorb EMR at a specific frequency which is different for each atom and molecule. The reason is every atom and molecule absorbs EMR at a different frequency is the they each have different energy level since there is a different amount of electrons in each atom and molecule. These energy levels are unique and distinct like a finger print; the spectral lines in spectroscopy are the energy levels in each atom and molecule and this allows us to determine what the chemical composition of a planets atmosphere is by the absorption of the Sun light at specific wavelengths by the gases in an atmosphere. The spectral lines are black lines which show what color of light a gas absorbs as the sunlight passes through the atmosphere and reflects off it’s surface and back into the telescopes spectrometer. These black absorption lines are in different colors for each gas, but a particular gas will always have the same lines unique to it which allows us to compare the lines to known gas and identify it. This will allow us to detect the different gases and their chemical composition in an exoplanets atmosphere. The James Web space telescope has this capability.

Actually the majority of the earth’s surface has a pressure greater then Venus.

The famous Fraunhofer lines

There aren’t more a few gases that can do that. CO2-H2 (for example, 90% CO2 and 10% H2 in just *a bar* atmosphere) collision-induced absorption can maintain the surface temperature to be greater than freezing-point at 2AU, which is already beyond any possible CO2-CH4 greenhouse effect.

Venus has a surface pressure of 90 bars. The Earth has only one bar so Venus has ninety times the atmosphere of Earth. This fact is proven by American and Russian probes which landed on the surface. Also There are radio occultation experiments when the spacecraft passes behind Venus which corroborate the surface pressure of 90 bars. The chemical composition of Venus is 96 percent carbon dioxide, and 3.5 percent Nitrogen, and argon, sulfur dioxide and water vapor less than one percent. The greenhouse effect causes the surface Venus to be hotter than Mercury even though Mercury much closer to the Sun than Venus.

Sorry, I did not mean to be so obtuse but the majority of the earth’s surface which is below sea level of 1 kilometer has a pressure of over 100 bar. It gives a little perspective on how we look at the universe from a very thin layer of earth’s atmosphere, but the earth is mostly covered by water! If you would like to see what the majority of the earth looks like you are welcome to come visit me in the Philippines and go diving on the coral reefs in front of our home.

In which case, the “surface pressures” of water worlds would be “colossal”. ;)

Quote from Nicky: “There aren’t more a few gases that can do that. CO2-H2 (for example, 90% CO2 and 10% H2 in just *a bar* atmosphere) collision-induced absorption can maintain the surface temperature to be greater than freezing-point at 2AU, which is already beyond any possible CO2-CH4 greenhouse effect.” This is not correct. An atmosphere of one bar with 90 percent Co2 would have a very strong greenhouse effect since most of is Co2. As I already wrote C02 is a greehouse gas and molecular hydrogen is not and would not contribute much of a greenhouse effect as compared to Co2. The 90 percent Co2 in a one bar atmosphere would be the cause of the greenhouse effect.

That is not my opinion, that is the result of many works done on climate modeling by generations of planetary scientists, including Ramses Ramirez who just simulated greenhouse effect of H2 and CO2-H2 atmosphere, so you are basically saying that all the climate models are incorrect beside your own thought experiment.

At 2 AU, even 10 bars of CO2 alone cannot maintain temperate surface because of strong scattering effect of CO2, which is why traditional maximum greenhouse limit (CO2 atmosphere) only extends to 1.7 AU.

90% CO2 and 10% H2 warming is not what I said. It is based on recent 1D radiative-convective climate model published by Ramirez and Kaltenegger.

See Ramirez, R. M., & Kaltenegger, L. (2017). A volcanic hydrogen habitable zone. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 837(1), L4.

The paper posted by Alex Tolley is an example.

To Geoffrey et al. : There is some confusion about how collision-induced absorption works. Although H2 is not *normally* a greenhouse gas, the H2 in the CO2-H2 or N2-H2 collision-induced pair can effectively become a greenhouse gas under the right circumstances. The reason for this is because the background gas (e.g. CO2 or N2), at high enough atmospheric pressures, can excite the rototranslational states of H2 through “foreign broadening”. Because H2 is a light enough molecule, quantum mechanical concerns dictate that these excited (and “normally forbidden”) states of H2 absorb over a large swath of the thermal IR, including in regions where CO2 and H2O absorb poorly. This is why the CO2-H2 (or N2-H2.. any background gas would really do at high enough pressures) collision induced pair is so potent. Absorption by the pair fills up the spectral “gaps” where CO2 and H2O do not absorb very well (the so-called window regions), giving you that extra bang.

The extra heating from Co2-H2 makes it more potent than pure CO2 for yet another reason. At far enough distances from the star, CO2 likes to condense (possibly leading to atmospheric collapse in certain circumstances) and some of that greenhouse effect is lost. However, the extra heating from Co2-H2 collision-induced absorption, for instance, can help minimize these cooling effects, another reason why the Co2-H2 HZ outer edge extends beyond the classical Co2 outer edge.

The collision-induced phenomenon is best explained in the following paper:

Kasting, James F. “How Was Early Earth Kept Warm?.” Science 339.6115 (2013): 44-45.

We also discuss this some in our 2014 Mars paper:

Ramirez, Ramses M., et al. “Warming early Mars with CO 2 and H 2.” Nature Geoscience 7.1 (2014): 59.

I hope that clears things up.

I see the Nationak Academy of Sciences ,Engineering and Medicine have chaired by Scott Guadi ( also chair of the Decadel Habex STDT) just released a laudable report with the “aspirational” recommendation of prioritising a HabEx like direct imaging telescope. Whilst admiring and agreeing with the recommendation for a space telescopic habitable exoplanet characteriser, it’s the word aspirational that lets this down for me . Thats exactly what JWST has become as NASA hugely underestimated the technological challenges (and thus cost) involved in building it .

HabEX unlike JWST is a monolithic telescope ,with none of the hideously complex design requirements now evident for a deployable scope and its huge sunshade. Something that is ironically likely to be rendered redundant with the far bigger payload fairings of upcoming EELVs like Blue Origjn’s New Glenn and ULA’s Vulcan. More so still by the BFR within the decade. ( with a fairing width of 9m that pretty much means up to the maximum sized 8m monolithic mirror could be accommodated )

Monolithic it might be but HabEX will instead be dogged with still many underdeveloped nee unproven technologies required for the uber precision and stability requirements to deliver the ultra high contrast required for direct imaging the sort of temperate exoplanets that might yield measurable biosignatures. Even if approved it would likely spiral down a similarly disastrous trajectory to JWST.

So why not go with proven technology ? Perspirational rather than aspirational,

A rigid , large monolithic mirror as big (or indeed far larger than) HabEX’s 4m with a simple , passively cooled Visible /NIR sensor array and spectrograph behind it . This could easily be launched within the next decade utilising already preexisting transit spectroscopy for exoplanetary atmospheric characterisation . It would NOT have anything like the stringent technological requirements of a direct imaging scope .

Effectively EChO on steroids.

Hubble and Spitzer have already used this technique effectively for some years , limited only by their relatively small size and the time limitations imposed by wider scientific commitments. But still able to offer some atmospheric characterisation on the TRAPPIST-1 planets .

The ESA 1m ARIEL telescope will be the first such bespoke telescope within a decade and refine what is now an established and commonplace ,PROVEN technique .Possibly the 0.76m Nasa FINESSE even sooner. Not as good as the idyll of direct imaging admittedly, but unlike it , operational simply in the time required to build any such telescope. And still offering widespread exoplanet characteristisarion that can only be imagined .

Off the shelf.

ALL the technology is already at a high technological readiness level . It’s really only a matter of scale and telescope durability ( longer the simpler the design. ) that determines the number of transits required to build up (“bin”) a big enough SNR ( 5-10) for temperate planet atmospheric analysis around the kind of M class stars that already operational TESS will discover dozens of suitable planetary targets around.

More than capable of employing a spectroscopic bandwidth capable of identifying near ALL the proposed biosignatures proposed above. On already known planets , and unlike a direct imager ,with no wastage of precious mission time searching for elusive targets . Delivering a far bigger and meaningful sample size .

So why not rebadge HabEX into HabEChO ?

Very good in depth report on HabEx:

https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/habex/pdf/HabEx_Interim_Report.pdf

100 meter space telescope in the not to distant future:

https://www.nextbigfuture.com/2018/09/nasa-jpl-update-on-progress-to-assembling-giant-100-meter-space-telescopes-and-starshades.html/amp

Robotic Assembly of Space Assets: Architectures and Technologies:

https://exoplanets.nasa.gov/internal_resources/914/

What is most interesting in the last two articles is the use of a crab like AI robot to assemble the array of mirrors. This could be a very useful item for many space missions and by increasing it to eight arms, could use four of the arms to do assembly of four different components or parts at once. This would be similar to an octopus with its tentacles having some intelligence to do autonomous operations with the central AI learning and checking the final result. Floating around in zero g is similar to being buoyant in the ocean!

Guess the suction cups would not work in the vacuum of space??? :-0

A brilliant comment Ashley. I learned a lot from it.

Thanks Gary.

It’s only fair to say that there is trade off involved for this technique. Transit spectroscopy employs a number of separate processes with the most practical being transmission spectroscopy. This involves spectroscopically analysing light from that element of host starlight that passes through the planetary atmosphere at its outer limb as its passes out of or into transit . So called “primary eclipse” . In other words cross sectionally at the planetary terminator . A consequence of this is that the light refracts outwards as it passes through the atmosphere – away from the surface of any terrestrial planet . This effect is more pronounced the shorter the wavelength of the starlight such that for host stars earlier than about M2 spectrum , it would pass outside the “tropopause”, the theoretical outer limit of the troposphere . The inner most atmospheric layer lying on the planetary surface of a hypothetical temperate planet.

Most of the atmosphere as we know it here on Earth ( and which contains its life ) lies within the troposphere which extends 10-20 miles above ground level. Any biosignature gases would thus most likely be found here . So temperate terrestrial planets around M2 stars or later ,if they exist, could have their tropospheres assessed by transmission spectroscopy for tell tale absorption peaks .

For any planets around earlier ,hotter stars , the much more difficult technique of “secondary eclipse” spectroscopy would need to be employed . This would be difficult as it involves subtracting the ( very faint ) reflection of the “dayside” light of a prospective planet as it is just about to pass BEHIND its parent star, from that of the star alone during the subsequent eclipse period. We are talking seriously small units here even by already small exoplanet standards.

This technique has been indeed used successfully , but so far only for a small number of very large and close in “Hot Jupiters” ( consequently relatively bright as compared to the host star ) . Using it for much smaller and further out terrestrial type planets with shallow atmospheres would presumably require an order of magnitude or more increase in sensitivity for success. But it is surely theoretically positive and would only require a change of instrument scale rather than technological development .

Direct imaging has got to be the long term goal but it is clear that even after over a decade of development that the various technologies required are only slowly coming to fruition and still far from complete. The number of exoplanets is increasing all the time and simple large numbers are no longer to move forward characterisation . The lessons if JWST are stark . Don’t over stretch on technological development and if there is an easier and established way for detailed atmospheric characterisation , readily available -rather than aspired too – then it should be pursued immediately. The very fact that ARIEL and FINESSE are being considered so seriously for smaller cost capped budgetary programmes is because they are proven and ready . All that is now needed is to pump up the budget where there is a near linear relationship between outlay and telescope size.

NASA work on about $44 million per 10cm telescope aperture so even with crude extrapolation an 8m transit scope would cost around $3.3 billion .

Far,far less than even half of JWST to date and with much less likelihood of unexpected increases .

An 8 meter in space for 3.3 billion, would love to see it and see thru it! Could the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway (LOP-G) and this telescope be set to meet at the 43,000 apogee? This would make it easy to do upgrades to the scope and could still have it orbit at a higher apogee. Would there be a stable halo orbit it could use?

The best orbit for continuous exoplanet imaging of any type is always a “halo” around the Sun/Earth Lagrange 2 point – about a million miles directly outwards from the Earth’s orbit. It gives a wide field of view well way from any obstruction caused by the moon and Sun. Almost as good but time limited ( though somewhat easier and cheaper to reach – any telescope /.instrument cost will have the add on cost of its launcher and operations over time ) is an Earth trailing orbit such as is ulised by the Spitzer and Kepler observatories .

Quote by Ramses Ramirez: “Because H2 is a light enough molecule, quantum mechanical concerns dictate that these excited (and “normally forbidden”) states of H2 absorb over a large swath of the thermal IR, including in regions where CO2 and H2O absorb poorly.” This is not correct. Molecular hydrogen absorbs at its ground state in the ultra violet frequency. The higher energy levels don’t matter. Why? The ground state is what causes a molecule to vibrate and rotate which is quantum mechanical and it is the lower atmosphere or troposphere where the collision of molecules matter where the pressure is greatest. Infra red absorption of molecular hydrogen is used to study stellar nurseries or the upper atmosphere which contributes little to any greenhouse effect.

The sunlight hits the ground in the visible spectrum. The Earth’s surface heats up and re emits the energy in the infra red due to the conservation of energy law. When an infra red photon is absorbed by a Co2 molecule, it vibrates and rotates and re emits the photon in a random direction. The same photon hits another Co2 molecule and is absorbed and re emitted into the air. Consequently, the infra red thermal energy is slowed down from escaping to space, which is the greenhouse effect. The vibration of the Co2 molecules is what heats up the other gas molecules, molecular oxygen, Nitrogen etc which also vibrate. This effect occurs through the troposphere of a planet.

Geoffrey, I am sorry to say that you are not correct here. The reason for this is because your explanations ignore collision-induced absorption and foreign- (and self-) broadening. I have already explained it and it has been exhaustively shown in quantum spectroscopy. It can also be calculated by hand. Even infrared inactive gases like hydrogen can absorb in the thermal infrared at sufficiently high pressures. Moreover, both the overall atmospheric and hydrogen densities in the planetary atmospheres we are discussing here far exceed those in stellar nurseries or interstellar regions by many, *many* orders of magnitude. It is true that at low densities, this greenhouse effect is negligible. However, at high enough path lengths, corresponding to the atmospheres we are discussing here, the resultant greenhouse effect can be significant indeed.

Several papers detailing the physics have been mentioned in this thread. The HITRAN CIA paper is also pretty good:

Richard, Cyril, et al. “New section of the HITRAN database: Collision-induced absorption (CIA).” Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 113.11 (2012): 1276-1285.

A lot is riding on the James Webb Space telescope; It was designed to be big to look further into space to look for a big bang. I hope it has a long life and the shade works and keeps it cold. The spectroscopy is an additional benefit. I do like the idea of using transit spectroscopy for a telescope since it is off the shelf. Light polarization spectroscopy would be a nice extra.

It’s the infra red light that is slowed down from escaping into space.

I am anything but a wild and crazy Trekee…still I find this article interesting as it was written by a geologist. The idea of various classifications of types of exoplanets (taken from Star Trek) has some merit that perhaps should be considered. There have been several ideas taken from some SF that we have been put to use…just maybe this is another one. “Live long and prosper”

https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidbressan/2018/09/08/strange-new-worlds-the-geology-of-star-treks-planets/#2c04caea4ca7

Geologists (planetary or Earth) will tend to see classifications based on their interests and knowledge base. Biologists might see different classifications, perhaps based on metabolisms, state of evolution, etc.

Video depictions of worlds tend to be limited based on set locations available. British SciFi shows like Doctor Who, Blake’s Seven tend to be very limited, with quarries, heaths and woodland being the only options. US locations are more diverse.

As we increasingly use computer rendering of environments on green screens, I would hope the imagination of the shows and movies becomes greater in their depictions. Avatar’s life forms were a step in the right direction, although still recognizably derived from Earth forms. More imaginitive are Wayne Barlowe’s creatures, e.g. in the book Expedition, which was made into an animated “documentary”, Alien Planet. I suppose I am making teh same sort of plea as others have made for better scripts, in this case employing good consultants and listening to them. I tend to get really anoyed when a planet is depicted with having very few different species, and often with large predatory species hungry for spacesuited humans, and living in what appears to be a wilderness without any prey.

I couldn’t agree more, and write hard science fiction for just that reason.

Much of what is currently posted on my website http://www.davidpaxauthor.com is about human interaction with technology, as opposed to exobiology, but it is an area I’d be interested in developing. When we look at the body plans that have gone extinct on our own planet it’s clear that our own form is derived from a particular set of environmental circumstances, and life on other planets could develop in a variety of other forms.

The exited states of hydrogen only emit and absorb infrared at high temperatures, the paschen series, etc. These environments are in interstellar gas clouds, planetary nebula, stellar nurseries etc.

Diatomic hydrogen or molecular hydrogen’s ground state and exited states are different than atomic hydrogen. Molecular hydrogen is collisionally exited at the ground state with collisions is in mid infra the near infra red for ground level vibrational transitions. H2’s exited states are in the ultra violet, so we are both wrong. http://w.astro.berkeley.edu/~ay216/05/NOTES/Lecture18.pdf

Stellar nurseries and gas clouds in space is the only place where those collisions of H2 occur where we get the infra red emission and near infra red.

High pressure hydrogen is only found on gas giants like Jupiter or Saturn and not Earth like exoplanets. Hydrogen always floats up to the stratosphere like helium balloons where the pressure is low and does not contribute much to a greenhouse effect on Earth sized planets. It would be the same for Super Earths. Molecular hydrogen is not considered a greenhouse gas,

Ramses Ramirez, I agree with you about the collisions of molecules for heat, but it is not just the greater pressure that causes the greenhouse effect in a thicker atmosphere say four bars. There are more molecules in a thicker atmosphere which causes more scattering of long wave radiation, the infra red radiation even if the gases are not greenhouse gases. Furthermore, greenhouse gases like Co2, Ch4, NO2, O3, etc always scatter more infra red radiation than non greenhouse gases at all pressures. It’s the radiational heating or infra red absorption (thermal radiation) that causes the Co2 or any other greenhouse molecule to vibrate and rotate which warms the air.

Some interesting new material:

Habitability of Exoplanet Waterworlds:

30 Aug 2018

“Many habitable zone exoplanets are expected to form with water mass fractions higher than that of the Earth. For rocky exoplanets with 10-1000x Earth’s H2O but without H2, we model the multi-Gyr evolution of ocean temperature and chemistry, taking into account C partitioning, high-pressure ice phases, and atmosphere-lithosphere exchange. Within our model, for Sun-like stars, we find that: (1)~the duration of habitable surface water is strongly affected by ocean chemistry; (2)~possible ocean pH spans a wide range; (3)~surprisingly, many waterworlds retain habitable surface water for >1 Gyr, and (contrary to previous claims) this longevity does not necessarily involve geochemical cycling. The key to this cycle-independent planetary habitability is that C exchange between the convecting mantle and the water ocean is curtailed by seafloor pressure on waterworlds, so the planet is stuck with the ocean mass and ocean cations that it acquires during the first 1% of its history. In our model, the sum of positive charges leached from the planetary crust by early water-rock interactions is – coincidentally – often within an order of magnitude of the early-acquired atmosphere+ocean inorganic C inventory overlaps. As a result, pCO2 is frequently in the “sweet spot” (0.2-20 bar) for which the range of semimajor axis that permits surface liquid water is about as wide as it can be. Because the width of the HZ in semimajor axis defines (for Sun-like stars) the maximum possible time span of surface habitability, this effect allows for Gyr of habitability as the star brightens. We illustrate our findings by using the output of an ensemble of N-body simulations as input to our waterworld evolution code. Thus (for the first time in an end-to-end calculation) we show that chance variation of initial conditions, with no need for geochemical cycling, can yield multi-Gyr surface habitability on waterworlds.”

https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.00748

Identifying inflated super-Earths and photo-evaporated cores:

5 Sep 2018

“We present empirical evidence, supported by a planet formation model, to show that the curve R/R?=1.05(F/F?)0.11 approximates the location of the so-called photo-evaporation valley. Planets below that curve are likely to have experienced complete photo-evaporation, and planets just above it appear to have inflated radii; thus we identify a new population of inflated super-Earths and mini-Neptunes. Our N-body simulations are set within an evolving protoplanetary disk and include prescriptions for orbital migration, gas accretion, and atmospheric loss due to giant impacts. Our simulated systems broadly match the sizes and periods of super-Earths in the Kepler catalog. They also reproduce the relative sizes of adjacent planets in the same system, with the exception of planet pairs that straddle the photo-evaporation valley. This latter group is populated by planet pairs with either very large or very small size ratios (Rout/Rin?1 or Rout/Rin?1) and a dearth of size ratios near unity. It appears that this feature could be reproduced if the planet outside the photo-evaporation valley (typically the outer planet, but some times not) has its atmosphere significantly expanded by stellar irradiation. This new population of planets may be ideal targets for future transit spectroscopy observations with the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope.”

https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.05069

Continuous reorientation of synchronous terrestrial planets controlled by mantle convection:

4 Sep 2018

“A large fraction of known rocky exoplanets are expected to have been spun-down to a state of synchronous rotation, including temperate ones. Studies about the atmospheric and surface processes occurring on such planets thus assume that the day/night sides are fixed with respect to the surface over geological timescales. Here we show that this should not be the case for many synchronous exoplanets. This is due to True Polar Wander (TPW), a well known process occurring on Earth and in the Solar System that can reorient a planet without changing the orientation of its rotational angular momentum with respect to an inertial reference frame. As on Earth, convection in the mantle of rocky exoplanets should continuously distort their inertia tensor, causing reorientation. Moreover, we show that this reorientation is made very efficient by the slower rotation rate of synchronous planets. This is due to the weakness of their combined rotational/tidal bulge—the main stabilizing factor limiting TPW. Stabilization by an elastic lithosphere is also shown to be inefficient. We thus expect the axes of smallest and largest moment of inertia to change continuously over time but to remain closely aligned with the star-planet and orbital axes, respectively.”

https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.01150

Abrupt climate transition of icy worlds from snowball to moist or runaway greenhouse:

5 Sep 2018

”

Ongoing and future space missions aim to identify potentially habitable planets in our Solar System and beyond. Planetary habitability is determined not only by a planet’s current stellar insolation and atmospheric properties, but also by the evolutionary history of its climate. It has been suggested that icy planets and moons become habitable after their initial ice shield melts as their host stars brighten. Here we show from global climate model simulations that a habitable state is not achieved in the climatic evolution of those icy planets and moons that possess an inactive carbonate-silicate cycle and low concentrations of greenhouse gases. Examples for such planetary bodies are the icy moons Europa and Enceladus, and certain icy exoplanets orbiting G and F stars. We find that the stellar fluxes that are required to overcome a planet’s initial snowball state are so large that they lead to significant water loss and preclude a habitable planet. Specifically, they exceed the moist greenhouse limit, at which water vapour accumulates at high altitudes where it can readily escape, or the runaway greenhouse limit, at which the strength of the greenhouse increases until the oceans boil away. We suggest that some icy planetary bodies may transition directly to a moist or runaway greenhouse without passing through a habitable Earth-like state.”

https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.01418

Differences in water vapor radiative transfer among 1D models can significantly affect the inner edge of the habitable zone:

5 Sep 2018

“An accurate estimate of the inner edge of the habitable zone is critical for determining which exoplanets are potentially habitable and for designing future telescopes to observe them. Here, we explore differences in estimating the inner edge among seven one-dimensional (1D) radiative transfer models: two line-by-line codes (SMART and LBLRTM) as well as five band codes (CAM3, CAM4_Wolf, LMDG, SBDART, and AM2) that are currently being used in global climate models. We compare radiative fluxes and spectra in clear-sky conditions around G- and M-stars, with fixed moist adiabatic profiles for surface temperatures from 250 to 360 K. We find that divergences among the models arise mainly from large uncertainties in water vapor absorption in the window region (10 um) and in the region between 0.2 and 1.5 um. Differences in outgoing longwave radiation increase with surface temperature and reach 10-20 Wm^-2; differences in shortwave reach up to 60 Wm^-2, especially at the surface and in the troposphere, and are larger for an M-dwarf spectrum than a solar spectrum. Differences between the two line-by-line models are significant, although smaller than among the band models. Our results imply that the uncertainty in estimating the insolation threshold of the inner edge (the runaway greenhouse limit) due only to clear-sky radiative transfer is ~10% of modern Earth’s solar constant (i.e., ~34 Wm^-2 in global mean) among band models and ~3% between the two line-by-line models. These comparisons show that future work is needed focusing on improving water vapor absorption coefficients in both shortwave and longwave, as well as on increasing the resolution of stellar spectra in broadband models.”

https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.01397

The 0.8-4.5µm broadband transmission spectra of TRAPPIST-1 planets:

2 Sep 2018

“The TRAPPIST-1 planetary system represents an exceptional opportunity for the atmospheric characterization of temperate terrestrial exoplanets with the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Assessing the potential impact of stellar contamination on the planets’ transit transmission spectra is an essential precursor step to this characterization. Planetary transits themselves can be used to scan the stellar photosphere and to constrain its heterogeneity through transit depth variations in time and wavelength. In this context, we present our analysis of 169 transits observed in the optical from space with K2 and from the ground with the SPECULOOS and Liverpool telescopes. Combining our measured transit depths with literature results gathered in the mid/near-IR with Spitzer/IRAC and HST/WFC3, we construct the broadband transmission spectra of the TRAPPIST-1 planets over the 0.8-4.5 ?m spectral range. While planets b, d, and f spectra show some structures at the 200-300ppm level, the four others are globally flat. Even if we cannot discard their instrumental origins, two scenarios seem to be favored by the data: a stellar photosphere dominated by a few high-latitude giant (cold) spots, or, alternatively, by a few small and hot (3500-4000K) faculae. In both cases, the stellar contamination of the transit transmission spectra is expected to be less dramatic than predicted in recent papers. Nevertheless, based on our results, stellar contamination can still be of comparable or greater order than planetary atmospheric signals at certain wavelengths. Understanding and correcting the effects of stellar heterogeneity therefore appears essential to prepare the exploration of TRAPPIST-1’s with JWST.”

https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.01402

New Species of Translucent, Gelatinous Fish Discovered in the Deep Sea:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/new-species-translucent-gelatinous-fish-discovered-deep-sea-180970259/

Scientists discover new sea creatures in depths of Pacific Ocean:

https://www.smh.com.au/environment/sustainability/scientists-discover-new-sea-creatures-in-depths-of-pacific-ocean-20180912-p5038m.html

The Closest Exoplanet to Earth Could Be ‘Highly Habitable’

https://www.livescience.com/63546-proxima-b-nearest-exoplanet-habitable.html

Habitable Climate Scenarios for Proxima Centauri b with a Dynamic Ocean.

Anthony D. Del Genio, Michael J. Way, David S. Amundsen, Igor Aleinov, Maxwell Kelley, Nancy Y. Kiang, and Thomas L. Clune

Published Online: 5 Sep 2018

Doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2017.1760

Article

Abstract

“The nearby exoplanet Proxima Centauri b will be a prime future target for characterization, despite questions about its retention of water. Climate models with static oceans suggest that Proxima b could harbor a small dayside surface ocean despite its weak instellation. We present the first climate simulations of Proxima b with a dynamic ocean. We find that an ocean-covered Proxima b could have a much broader area of surface liquid water but at much colder temperatures than previously suggested, due to ocean heat transport and/or depression of the freezing point by salinity. Elevated greenhouse gas concentrations do not necessarily produce more open ocean because of dynamical regime transitions between a state with an equatorial Rossby–Kelvin wave pattern and a state with a day–night circulation. For an evolutionary path leading to a highly saline ocean, Proxima b could be an inhabited, mostly open ocean planet with halophilic life. A freshwater ocean produces a smaller liquid region than does an Earth salinity ocean. An ocean planet in 3:2 spin–orbit resonance has a permanent tropical waterbelt for moderate eccentricity. A larger versus smaller area of surface liquid water for similar equilibrium temperature may be distinguishable by using the amplitude of the thermal phase curve. Simulations of Proxima Centauri b may be a model for the habitability of weakly irradiated planets orbiting slightly cooler or warmer stars, for example, in the TRAPPIST-1, LHS 1140, GJ 273, and GJ 3293 systems.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/ast.2017.1760

Pardon me. O3 or ozone is not a greenhouse gas since it only absorbs in the ultra violet. I should have written Co2, N20 (nitrous oxide) N02 nitrogen dioxide CO (carbon monoxide). CH4, etc.