I’m keeping an eye on the recent attention being paid to Proxima Centauri c, the putative planet whose image may have been spotted by careful analysis of data from the SPHERE (Spectro-Polarimetric High-Contrast Exoplanet Research) imager mounted on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope. A detection by direct imaging of a planet found first by radial velocity methods would be a unique event, and the fact that this might be a planet in the nearest star system to our own makes the story even more interesting.

I hasten to add that this is not Proxima b, the intriguing planet in the star’s habitable zone, but the much larger candidate world, likely a mini-Neptune, that has been identified but not yet confirmed. Proxima Centauri c could use a follow-up to establish its identity, and this direct imaging work would fit the bill if it holds up. But for now, the planet is still a candidate rather than a known world. From the paper:

While we are not able to provide a firm detection of Proxima c, we found a possible candidate that has a rather low probability of being a false alarm. If our direct NIR/optical detection of Proxima c is confirmed (and the comparison with early Gaia results indicates that we should take it with extreme caution), it would be the first optical counterpart of a planet discovered from radial velocities. A dedicated survey to look for RV planets with SPHERE lead to non-detections (Zurlo et al. 2018b).

But we’re not far enough along to spend much time on this in these pages — a great deal of follow-up work will be needed to nail down what is at best an unlikely catch. I call it that because it strains credulity to believe that we would find a planet whose mass suggests a world far less bright than this one is (if indeed it is a planet), with a luminosity that demands something like a huge ring system to explain it. Other explanations will need to be ruled out, and that’s going to take time. The radial velocity work on Proxima Centauri c points to a world of a minimum six Earth masses, orbiting 1.5 AU out. But if this direct imaging work has indeed identified (and confirmed) Proxima c, it is a planet with a most unusual makeup:

If real, the detected object (contrast of about 16-17 mag in the H-band) is clearly too bright to be the RV [radial velocity] planet seen due to its intrinsic emission; it should then be circumplanetary material shining through reflected star-light. In this case we envision either a conspicuous ring system (Arnold & Schneider 2004), or dust production by collisions within a swarm of satellites (Kennedy & Wyatt 2011; Tamayo 2014), or evaporation of dust boosting the planet luminosity (see e.g. Wang & Dai 2019). This would be unusual for extrasolar planets, with Fomalhaut b (Kalas et al. 2008), for which there is no dynamical mass determination, as the only other possible example. Proxima c candidate is then ideal for follow-up with RVs observations, near IR imaging, polarimetry, and millimetric observations.

So good for Raffaele Gratton (INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Italy) and colleagues for pursuing this investigation and for suggesting the numerous ways it can be approached with various follow-up methods. And kudos to Mario Damasso (Astrophysical Observatory of Turin) as well. Damasso was lead author of the discovery paper on Proxima Centauri c, and it was he who suggested to Gratton that the SPHERE instrument might just be able to detect it.

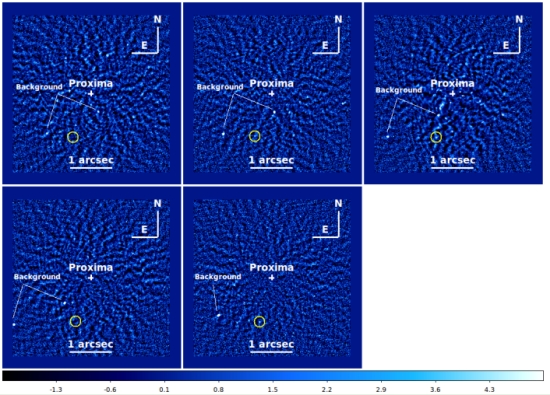

Now we have a wait on our hands before we have anything definitive. At this point we have a possible detection that is tantalizing but definitely no more than tentative. Meanwhile, here’s a figure from the paper that gives an idea what Gratton and team are talking about.

Image: This is Figure 2 from the paper. The SPHERE images were acquired during four years through a survey called SHINE, and as the authors note, “We did not obtain a clear detection.” The figure caption in the paper reads like this: Fig. 2. Individual S/N maps for the five 2018 epochs. From left to right: Top row: MJD 58222, 58227, 58244; bottom row: 58257, 58288. The candidate counterpart of Proxima c is circled. Note the presence of some bright background sources not subtracted from the individual images. However, they move rapidly due to the large proper motion of Proxima, so that they are not as clear in the median image of Figure 1. The colour bar is the S/N. S/N detection is at S/N=2.2 (MJD 58222), 3.4 (MJD 58227), 5.9 (MJD 58244), 1.2 (MJD=58257), and 4.1 (MJD58288). Credit: Gratton et al.

The paper is Gratton et al., “Searching for the near infrared counterpart of Proxima c using multi-epoch high contrast SPHERE data at VLT,” accepted at Astronomy & Astrophysics (abstract).

I was surprised that the paper does not discuss the effects of rings more. At spring and fall equinoxes the rings (hence the planet) should become invisible. When we see them from the star’s side, like with Saturn, they should be brighter than when lit from behind. (though not as dramatic as https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/cassini/whycassini/jpl/cassini20131112.html since we can’t see Proxima c from directly behind) The orbit is 5.2 years, yet the authors don’t include such a notion among their three explanations for why they didn’t see something in January 2016. It’s immensely more likely that I missed something here than they did, but I’m not sure what it is…

6G kind of excludes it. Otherwise if it had a breathable atmosphere, cool surface water, no tidal locking, adequate insolation (instellation?)and a clement radiation profile coupled with its (relative) proximity that could make it attractive for the next wave of human settlement – forty acres and a mule included.

40 acres and a robot included!

But robots don’t produce their own eventual replacements (and via unskilled labor, to top it off). If terrestrial grass, straw, and hay would would grow in the exoplanet’s soil, draft horses–I’m partial to Shires myself, due to their great size, strength, kindness (they are famous for–of their own accord–bending down so that a short person can put on their tack), and docility–would be ideal for doing all farm work, from harrowing to harvesting, plus they would fertilize the soil and provide transportation (riding, hauling tons of timber, crops, and other supplies, etc. [they also work at liberty to skid logs downhill]), and:

As “old-fashioned” as this seems, such arrangements have been studied–with positive conclusions–for space colonies of the sort large enough to have soil-grown crops. They don’t eat twice as much as light horses, as their size would suggest, but only about 40% more. Moreover (having slower metabolisms than light horses), they can eat low nutritional-content feeds, such as feeding straws, and thrive on it and grass.

John W. MacVey, in his 1984 book “Colonizing Other Worlds: A Field Guide” https://www.amazon.com/Colonizing-Other-Worlds-Field-Guide/dp/0812829433/ref=sr_1_2?dchild=1&keywords=Colonizing+Other+Worlds%3A+A+Field+Guide+by+John+W.+Macvey&qid=1588159713&s=books&sr=1-2 (www.abebooks.com also has it), wrote that bringing our own draft animals to other Earth-like worlds–and/or domesticating any similar, suitable native animals (he suggested that ox-like animals might be found on Earth-like planets)–would in many ways be more convenient, versatile, and efficient than relying on machines which require space parts–and an industrial infrastructure to produce them. (Even today, many draft horse-powered [from their fields to their sugar mills to their transportation of the produce to distributors, with self-fertilization] family farms–and not just among the Amish, Mennonites, and Hutterites–operate profitably, in North America and Europe [they still deliver beer and ale to pubs and taverns “on hoof,” too].) Also:

The mares can even be milked (and will produce “extra,” “replacement” milk for their foals [most mares’ udders are so small that obtaining worthwhile amounts for human consumption requires large herds and/or frequent milking, but Shire mares’ udders are made to the same large scale as the rest of their bodies, being the brawny, buxom equine gentle giantesses that they are]). Other draft breeds (the Jutlander, Dutch Draft, Belgian, Brabant Belgian [Brabants often provide mare’s milk, in Europe], etc.) are also suitable for space colony and “terrestroid” exoplanet residency and work. They also provide an intangible but nonetheless important benefit–friendship, love, and willing and loyal collaboration (they *like* working with their human partners, pulling harrows, plows, and carts), plus:

Such mares’ milk would provide flavor variety, as well as supplement the volume of goats’ milk. (Goats were found in studies to be superior to cows for space colonies because they produce more milk per pound/kilogram of body mass, they can eat and digest far more normally inedible, fibrous crop plant residue than cows, and their hair–which of course grows back after being trimmed–is an excellent and renewable source of high-quality fibers for producing clothing [Angora goats are bred for textile production, and the nannies can also be milked].)

As strange as *this* might sound, Amish people–who are experts at this sort of agriculture and food preparation & packaging–might volunteer to help settle other worlds, and farm in space colonies. They do ^not^ eschew all technology (they even use computers, but *only* for book-keeping in their stores), but only technology that leads to pride (due to conspicuous consumption) and which distracts from their simple, faith-centered way of living.

Since others would manage space colonies’ systems and fly the starships and manage the exoplanet colonies, there is nothing about space colony life, or life on an exoplanet, that would conflict with their religious or social doctrines. As well, with their preferences for hand labor, mutual help (such as barn-raisings), self-sufficiency, and living close to the land, they would quickly identify native exoplanetary plants, trees, and other materials, such as suitable varieties of stone, that they could use for building houses, barns, sheds, fences, walls, sieves, and so forth (and they would pay heed to notices from their “English” fellow colonists [“the English” is their polite term for non-Amish people, even if they aren’t actually English] about any trees or other plants that analysis had shown to be toxic, even to the touch).

I have often thought that colonization of Earthlike worlds or habitats is best done by low-tech populations. Heinlein seemed to like the idea of self-sufficient, farmers of the era he was writing in. The more technology we need, the more difficult colonization becomes – the larger specialized populations to work in the much larger technological infrastructure needed. We are experiencing the breakdown of such technological networks during the current pandemic.

Just as the idea of seed ships is used to reduce the immediate need for a readymade colony, so perhaps the best way to colonize a new environment may be to grow a civilization from a much simpler technological community.

I agree–the space colony studies and agricultural experiments showed that high-technology methods aren’t necessary. Basic, terrestrial agriculture–including the simple, draft animal-powered (and fertilized) type–can also be employed in Kalpana- and O’Neill-type space colonies, along with (for some crops) hydroponic and aeroponic agriculture (whose technologies have been considerably simplified via experimentation; simple foam boards to support the aeroponic crop plants such as tubers [potatoes, sweet potatoes, etc.], along with fans blowing super-saturated moist air containing nutrients, is now home DIY [“Do-It Yourself”]-level ‘garage technology’).

To optimize on growing space, “regular ‘meat-and-potatoes’-type meal crops” (potatoes, sweet potatoes, carrots, corn, peas, beans, onions, garlic, rice, wheat, etc.) could be grown in soil “Ye auld Terran way,” while more specialty/spice-type crops (bell peppers, Italian & jalapeño peppers, yellow squash, okra, zucchini, green beans, cabbage, vanilla beans, tropical fruits, and so forth) could be grown in compact hydroponic and/or aeroponic “greenhouses.” The animals’ solid waste also provides growing “beds” (I forget the technical name) for growing edible fungi such as field mushrooms (the common grocery store variety used on pizzas and in spaghetti sauce, also called button mushrooms), Shiitake and the numerous “gourmet” mushroom varieties (some have flavors like scrambled eggs, etc.), and truffles (not my favorite edible fungus, but many people love ’em).

Fruit and nut trees (apple, pear, cherry, peach, lemon, lime, walnut, pecan, etc.) could double as decorative and shade trees in the parks (O’Neill’s studies came to this conclusion). Fish–raised in tanks or ponds–would provide meat and protein-rich fish meal for other farm animals, goats (and draft horse and pony mares) would provide milk, and chickens would provide eggs and meat (rabbits proved most efficient for meat, but many people–at least in the U.S.–don’t find it particularly “culinarily alluring”).

Beef (and dairy) cattle would be inefficient, but goat–and mare–milk are equal-to-superior (nutritionally and in flavor) replacements. (I drink goat milk and use it on cereal for these reasons [ditto for mare’s milk, if I could get it locally; I can only order powdered mare’s milk–both make rich milkshakes, too!].) Goat milk also makes excellent soap (which I also use), and goat hair–especially Angora goat hair–is a good textile fiber for making clothing, blankets, and so forth. (So is Angora rabbit hair, which is great for knitting sweaters, among other things; a couple in Michigan I knew made their clothes courtesy of Frida, their [large] pet Angora rabbit.) As well:

Growing one’s own crops, and raising and working with goats and draft horses & ponies (and riding, driving, and skidding felled logs with them, as they could double as transportation and freight haulers in space colonies), creates an intangible yet essential being-to-being connection and happiness, which tending and/or programming agricultural robots or food production machinery can never replace.

Having returned home after riding my mare as long-distance transportation, it was wonderful to reflect that *WE* were out doing that up in the Blue Ridge Mountains for days at a time, as I massaged her tired legs, back, hips, neck, and withers; I never felt that–or ever got an appreciative nuzzle and whicker–from my truck. If/when we settle among the stars, it must be as we are, or the changes will take away from rather than add to people’s humanity (most people–myself included–wouldn’t even entertain the notion of going, under such terms).

I prefer nature in its natural form, this is one of the reasons we are in this situation now, both warming and disease. The problem is which comes first robots or animals. We not talking about your wood chopping tin man but a full utility vehicle that would be beyond our comprehension, even to the level of terraforming. Some of our old ways need to die, meat eating is a prime example. The ability to produce most of what we need from a very advanced 3D printing system would keep things running. Take as much as possible in eggs, seeds and whatever else could help after the planet is livable enough to handle it. Redundancy and Variety is the key to any success on these long range colonies and when the time comes send out the Amish.

My parents came from the Pennsylvania Dutch area but my mother’s side is of lineage from the Winslow’s of the Mayflower and Plymouth colony. My Father’s side is from the Peter Fidler lineage of Hudson Bay Company and explored and mapped much of central and western Canada. His side also had the Sitgreaves that explored the Zuni and Colorado Rivers in 1851.

The reason I bring this up is the appalling situation that has developed in the Mason’s ideal of America.We need to get off this planet, for the planet is sick of us and we are becoming sick in the sense of a free society. It is time for a light to shine in the heavens that will lead us to a better human race.

But that is the problem. Bring sophisticated robots and eventually they start to fail. The colony scavenges parts to keep a slowly decreasing number operational. Unless you build the infrastructure to replicate these machines, the colony will eventually lose their use. Life, OTOH, will replicate as long as the environment allows it. It can also adapt.

Asimov’s Solarians seemed to be able to live on large estates yet be served by humanoid robots that must have been relatively easy to build and repair. Nowhere in his worldbuilding was it evident how that could be achieved.

Maybe we can eventually build robots that are more like living organisms, built from unit cells that can self-repair and replicate, yet still, be independent of the local biosphere.

Yes, if we were leaving tomorrow but we are talking 50 years or more from now. Self replicating robots that can repair each other or themselves, this will be developed on the Mars colonies out of necessity. The environments on these planets will probably need genetically modified earth species to survive if free range. The bots will build large living areas for the humans but land will be too expensive for homesteading. The first thing set up will be camps, but will have to be self sufficient with large hydroponics stacked gardens combined with aquaculture to form man made ecosystems. This is something that will probably be developed in the large lunar lava tubes in the next 30 years. The fact is that all these ideas should be developed and bugs worked out in the next 50 years in the Mars and Lunar colonies. The AI bots should be well trained by then so the Proxima b colony will just need hibernation units during travel…

Great (I think) if this technology arrives, but it currently is magic pixie dust. Just consider what is required to construct microchips. While printers can construct simple parts like appendages or skeletons, the microfabrication is far more complex and requires a supporting industry just to manufacture the needed materials. Maybe we can print these chips simply in the future, but there is- nothing on the horizon that I see. As for Martian colonists doing this out of necessity, can you provide historical examples where a needed technology was developed by a colony in its early settlement rather than imported from the mother country? Your starter for ten points might be the cotton gin. But beyond that?

We will eventually have robot factories to churn out robots but they will be part of an industrialized civilization, possibly even a machine civilization rather than a human one.

I hear what you are saying, but right here in Bohol the move is to redevelope the agriculture secter since the resort industry has collapsed. But you can put a hell of a lot of CPU or GPU chips in a suitcases and have them installed on chipsets at the destination.

100% agree with you. Just as long as we understand that this means that the robots cannot self-replicate without these externally provided chips. Eventually. just like teh dinosaurs in Jurassic park needed lysine and evaded that by eating bananas, may the robots will learn how to bypass the limits on their replication.

Trying to colonize extrasolar planets as a “replacement” for Earth is just running away from ourselves and our problems (whose severity, in any event, I doubt; all my life, I’ve heard and read about several world-ending things, none of which have “delivered on their doom”).

Regarding eating meat, I–and you–have the combined grinding *and* fang teeth (and digestive tracts) of omnivores, and I worry about my nature as much as a bear does. Even herbivores, such as horses and ponies, will scavenge kills (and locations where people slaughter chickens and other meat animals), as well as eat offered fish when protein is scarce; I know horses here in Alaska who eat this way, and happily. This isn’t even limited to such situations, as many horses–in temperate regions, with plenty of grass, grain, and hay–enjoy roast beef, sausages, and hot dogs (my mare was one of these, and it was she who made the “I want some of *that*!” gestures and sounds).

Interstellar settlement, unless it is conducted as a positive, *additive*, and life-affirming activity (the activity of a prosperous, curious, happy within itself, and forward-looking civilization that ^doesn’t^ consider itself a “blight” upon nature [I have no patience for such people]), doesn’t interest me at all; I’d rather just see probes sent. Besides:

We don’t have to go far at all in order to settle space. Kalpana One-type space colonies built close to home–using terrestrial materials–would provide a 1 g, 1 atmosphere environment in which we, our pets, and domesticated and wild animals and plants would be healthy and happy. Building our own worlds, suited to our needs and wants, would be easier than trying to make a go of it on the Moon or Mars (small, Antarctic-type scientific bases with rotating staffs, not permanent settlements, make sense for such un-Earth-like worlds), and:

Just the greater volume of open spaces in space colonies, and the trees and fields, make a huge difference, as most people–myself included–will simply not be content living in a chain of connected “tin can” modules, or lava tubes, on an alien world. If sufficiently Earth-like–and reachable–exoplanets are found, where we could live as we live here on Earth, such worlds would make welcome additional homes, but I wouldn’t bet on finding any, at least that we could reach (and if we did, they could easily already be someone else’s property), but:

Such “Goldilocks planets” wouldn’t even be essential; any sufficiently warm and long-lived star (whose sunlight color was to our liking, and would drive photosynthesis of terrestrial plants), and which also possessed accessible resources such as in asteroids or low-gravity planetary moons, would be a new place in which to build space colonies. Plus:

Simply by selecting a desired orbital distance from the star (and/or by adding light-collecting mirrors, as needed), very large numbers of space colonies could “live” throughout the star system. The only real limitation would be around red dwarfs that are flare stars; one wouldn’t want to establish space colonies too close-in, to avoid the “gusts” of X-rays from the flaring events (but more distantly-orbiting colonies would do just fine, as would quite distant, solar mirror-equipped ones). As well:

Around intrinsically-brighter (brighter than our Sun, such as Sirius, Altair, Spica, etc.) stars, space colonies–provided that usable building materials and other resources were found orbiting the stars–could simply be established in more distant circum-stellar orbits, to ensure Sun-like light and heat fluxes on the space colonies.

It would be nice if Proxima Centauri c is a planet. That would behoove us to consider if there are additional planets orbiting Proxima Centauri. If such additional planets exist, then my co-authored book, “The Case For Pandora” would have strong future relevance. The other stars in the Proxima Centauri system might also have planets orbiting them.

Interesting. Didn’t know that there is a Proxima c candidate.

“Proxima c candidate is then ideal for follow-up with RVs observations, near IR imaging, polarimetry, and millimetric observations.”

It’s a pity that ALMA is closed due to the coronavirus.

This was clearly a demanding study. The authors obviously hoped to deliver a seminal direct imaging confirmation of an RV exoplanetary “discovery”. And failed. I’m sorry to rain on the Proxima parade but someone has to.

There are numerous systematic issues that they are forced to confront and admit.

Firstly that the presence of “Proxima c” is still only really a “signal” rather than a bone fide discovery.( though Proxima b started out like this too before being distilled into life by successive observations ) .

Secondly, the light signature of the SPHERE image ,though close , does not equate to the RV orbital parameters and is also far brighter than expected given the RV suggested mass. This paper was obviously submitted prior to the “undiscovery” of Fomalhaub b with which they make unfortunate comparisons . The obvious similarity between both Proxima c is described here and Fomalhaut b is that the two enabling technologies used in their discovery, SPHERE the Hubble telescope , we’re both operating at the extremes of their design capabilities. So systematic error derived artefacts must surely be considered as realistic explanations of the their findings. Though not stated explicitly in the text the tone is implicit throughout. Not least suggested by the recent “disappearance” of Fomelahaut b. Yet that doesn’t stop the facts ( such as they are) being made to fit a theory. For Fomelahaut b, a disintegrating dust cloud arising from the collision of two planetissmals. For Proxima c, either a Saturn like ring structure ( only much wider and brighter) or some sort of debris field. I’m only surprised that our old friends , the ubiquitous “get out of jail” exo comets haven’t been thrown in for good measure too.

The SPHERE polimametric imager is situated on the VLT Unit telescope 3. It is able to image in both visible 0.5-0.7 light – and near infrared too, as long as the 2.2 K band – through its IRDIS ( Infrared Dual imager spectrograph ) and IFS , integral field spectrograph . The polarimeter component increases its imaging ability significantly ( reflected exoplanet light is more likely to be polarised and thus can be removed to increase contrast reduction) but is diffraction limited to visible light. So the NIR IRDIS and IFS instruments are much less sensitive. This becomes more pronounced the longer the wavelengths and by the K band the thermal background of the sky becomes a limiting factor in the absence of cryogenic telescope cooling. ( it was for this reason that the mid infrared imaging , cryogenic instrument, VIRTIS, was used in the NEAR Alpha Centauri imaging attempt last year – moved to unit telescope 4 to exploit the extreme AO capacity of its potent deformable secondary mirror ) The J and H bands used in this work is at the extreme edge of viability for IRDIS which in turn works at the extreme edge of the SPHERE operating range. At these longer IR wavelengths the planet/star contrast is better but at the price of weakened optical aberration mitigation by SPHERE’s own extreme adaptive optics system. These aberrations will take the form of aptly named “speckles” in the field of view. It is this that casts severe doubt on the validity of any findings here. The “pictures” of Proxima c look suspiciously like speckles. A fact that is effectively conceded in the text.

The focus of the later sections and conclusion being on the Gaia DR3 release which will be sensitive enough to astrometrically constrain any Neptune or sub Neptune mass planets orbiting Proxima at AU and trans AU distances.

Saw this on ArXiv.org today and looks like it might be useful to bring Proxima Centauri c out of the speckles:

K-Stacker, an algorithm to hack the orbital parameters of planets hidden in high-contrast imaging. First applications to VLT SPHERE multi-epoch observations.

“Recent high-contrast imaging surveys, looking for planets in young, nearby systems showed evidence of a small number of giant planets at relatively large separation beyond typically 20 au where those surveys are the most sensitive. Access to smaller physical separations between 5 and 20 au is the next step for future planet imagers on 10 m telescopes and ELTs in order to bridge the gap with indirect techniques (radial velocity, transit, astrometry with Gaia). In that context, we recently proposed a new algorithm, Keplerian-Stacker, combining multiple observations acquired at different epochs and taking into account the orbital motion of a potential planet present in the images to boost the ultimate detection limit. We showed that this algorithm is able to find planets in time series of simulated images of SPHERE even when a planet remains undetected at one epoch. Here, we validate the K-Stacker algorithm performances on real SPHERE datasets, to demonstrate its resilience to instrumental speckles and the gain offered in terms of true detection. This will motivate future dedicated multi-epoch observation campaigns in high-contrast imaging to search for planets in emitted and reflected light. Results. We show that K-Stacker achieves high success rate when the SNR of the planet in the stacked image reaches 7. The improvement of the SNR ratio goes as the square root of the total exposure time. During the blind test and the redetection of HD 95086 b, and betaPic b, we highlight the ability of K-Stacker to find orbital solutions consistent with the ones derived by the state of the art MCMC orbital fitting techniques, confirming that in addition to the detection gain, K-Stacker offers the opportunity to characterize the most probable orbital solutions of the exoplanets recovered at low signal to noise.”

Interesting comments in the conclusion:

“We also searched for additional sub-stellar companions

around these two stars. We found two bright features, corresponding to two possible planets orbiting within the orbit of the

known companions. However, these two features are close to the

coronagraphic mask, and we will show in a dedicated analysis

that the one found around HD 95086 is a recombined “superspeckle”. The c candidate detected by K-Stacker around ? Pictoris without using prior information from the radial velocity

detection of ? Pictoris c is on a trajectory compatible with the

orbital parameters found by Lagrange et al. (2019b). But, the KStacker orbit is misaligned with the disk and the (S/N)KS ? 5 is

not high enough to claim that it is a true detection. Despite the

relatively large error bars on the euler angles (?, i, ?0) the 1 1 ?

agreement between the putative K-stacker detection and the radial velocity solution is encouraging and more observations are

required to constrain the orbital parameters and to determine if

at least a part of the light of this detection comes from ? Pictoris c.”

But will it work on the dim Red Dwarf Proxima???

Some interesting news for a new interstellar probe to reach Proxima and explore it.

Deceleration of Interstellar Spacecraft Utilizing Antimatter.

https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/spacetech/niac/2020_Phase_I_Phase_II/Deceleration_of_Interstellar_Spacecraft_Utilizing_Antimatter

ANTIMATTER SAIL CONCEPT

DONATE TO OUR KICKSTARTER.

http://hbartech.com/index.php/projects/antimatter-sail-concept/

An antimatter (antiprotons)-energized fission, Medusa-type “parachute-sail”…as has been said before about similarly far-out ideas, “it’s just crazy enough that it might work!” For really lightweight probes, it’s even conceivable that this braking sail–because the fission daughter products exert force against the concave interior surface of the sail (which I presume is electrostatically charged)–might serve as a *propulsion* system, rather than just as a brake (although the latter is equally important, being “the other side” of the starflight [with rendezvous with the target star] problem). Also:

Depending on the mission requirements, rendezvous (matching galactic orbit velocities with a target star, and then entering orbit around it or around one or more of its planets [and perhaps even moons]) might not be necessary; a relatively slow system “fly through” might suffice. In such a case, the imaging speed requirements would be less severe than those of the (now to be equipped with spherical sails, 1 to 4 meters in diameter) Breakthrough Starshot probes, which would dash through Proxima Centauri’s system (or the Alpha Centauri A & B system) at 20% of c. I would note, though, that getting multiple, clear pictures–even at that fantastic velocity–isn’t impossible, because the 1950s-vintage “Rapatronic” camera, which was developed to record minute details of nuclear test explosions, achieved a shutter speed of *one-billionth* of a second (and using film, no less)! An all-electronic version might well exceed even that shutter speed.

And all this high-speed camera at less than 1 gm in weight. I look forward to its development as it would have uses here on Earth if it was really small and low cost.

A latter-day Rapatronic extremely high shutter-speed camera need not be limited to < 1 g mass. Breakthrough Starshot isn't the only ride in town (although it is, at least for the present, the fastest).

So how are our 3 giant telescopes construction projects doing in this atmosphere of COVID-19, I would think the Chilean Andes would be relatively safe? I heard that some slow progress on JWST was happening, any updates. These four telescopes are what is needed to be able see Proxima C, unless someone tries imaging in UV after a large flare??? Yes, I agree the signal does looked like speckles, especially in the images in Fig. 4 of the article.

What the astrometry of Proxima C? The astrometry data should match the radial velocity data if there really is a planet there.

Regarding the Gaia results alluded to in the first quote, the astrometric orbit of Proxima c has been determined by two groups: Kervella, Arenou & Schneider (2020), and Benedict & McArthur (2020). Both of the astrometric determinations are consistent with each other but inconsistent with the position of the imaged candidate.

At the moment it doesn’t look possible to say for certain whether this reflects unaccounted-for systematic errors in one or more sets of measurements, and/or if there’s something else going on, e.g. an additional massive outer planet orbiting Proxima.

Can we look for it with the TESS data once we’re in the right part of the sky? I’m not sure which segment Alpha Proxima would be in or whether it will transit the star from our angle. Probably a naive question but I’m very interested! :)

Proxima b does not transit Proxima Centauri as seen from Earth so cannot observed by the Transit Exoplanet Survey Satellite , TESS. But even it did Proxima Centauri has a visual magnitude of just 14 and TESS has a limiting magnitude of 12.

Thank you Ashley.

How does the position given by sphere compare to the signal observe by Alma 1,6 UA from proxima?

“…So how are our 3 giant telescopes construction projects doing in this atmosphere of COVID-19, I would think the Chilean Andes would be relatively safe?…”

It’ll be the GMT that gets finished long before the other two do. Lowest technical/financial/political risk IMHO. But even then they are still making the mirrors and have only recently let the contract to build the structure. I’ll be amazed if it sees first light before 2028 alas. Very exciting but a long wait.

P