How does SETI fit into the long-term objectives of a civilization? To a society whose central project is communication, the ‘success’ of the project in detecting intelligence around another star is obviously not assured, but if it does find a signal, would it eventually receive an Encyclopedia Galactica? There is much to ponder here, and Nick Nielsen today tackles the question from the standpoint of not one but many Encylopedia Galacticas, spread out through cosmological time as opposed to the ‘snapshot’ version a finite species sees. Read on to consider the kinds of civilizations that might practice or be discovered by SETI and how they might formulate their listening and communications strategy. SETI is analyzed here as one of a variety of central projects Nielsen has examined in these pages and elsewhere. For more of his work, consult Grand Strategy: The View from Oregon, and Grand Strategy Annex.

by J. N. Nielsen

1. Variations on the Theme of Spacefaring Civilization

2. A Missed Opportunity

3. The SETI Paradigm

4. Space Development of SETI Civilizations

5. The First Edition of Encyclopedia Galactica: The Null Catalogue

6. Transformation of SETI in the Light of Technosignature Detection

7. Tensions Intrinsic to SETI Civilizations

8. The Success and Failure of Civilizations

9. The Civilizational-Cosmological Endgame

1. Variations on the Theme of Spacefaring Civilization

In my previous Centauri Dreams post Space Development Futures I formulated six scenarios for the future of civilization, based on six distinct central projects that could be the drivers of future civilization. My list of six central projects included the Enlightenment, science, environmentalism, traditionalism, virtualism (simulations and singulatarianism), and urbanism. But I wasn’t finished there.

In my newsletter 128 I came at the idea of the central project of a civilization from a different angle and briefly laid out four possible scenarios for future civilizations based on biocentric initiatives, which latter could be understood as continuous with the biocentric past of human civilization. Here my list included civilizations that focus on the propagation of terrestrial life on a cosmological scale [1], large-scale research into origins of life, an exhaustive survey of life in the cosmos, and the study of synthetic or artificial life, any or all of which might be taken together in a civilization that exemplified a special case of science as a central project, taking the biosciences in particular as a central project.

These speculations (six described in an earlier Centauri Dreams post and another four described in a newsletter) yield an even ten scenarios for future civilization. We could understand the bioscience scenarios as falling under the umbrella of scientific civilization, making them among “…a class of scenarios… that incrementally depart from the above generic scenarios, and continue to developmentally diverge…” as noted in Space Development Futures. In the same way, further scenarios that would fall under the umbrella of the other five scenarios I outlined could be formulated, yielding as many variations upon these themes as one has the imagination to generate.

However, these biological variations on the theme of scientific civilization touch on human identity in a fundamental way, and so stand out from other permutations of scientific central projects. There is an intrinsic reasonableness to human beings, being ourselves biological beings, being interested in biology in the same way that individuals are sometimes intensely interested in their family origins, and who then take to genealogical research in order to discover their roots. A biocentric-bioscience civilization (with its moral imperative derived from biotic ethics) would embody this human interest at the scale of civilization, discovering the roots of human life by discovering the roots of biology.

E. O. Wilson called our natural interest in living things biophila, and elaborated on the idea in a book devoted to the same intrinsic biological interest on the part of human beings:

“From infancy we concentrate happily on ourselves and other organisms. We learn to distinguish life from the inanimate and move toward it like moths to a porch light. Novelty and diversity are particularly esteemed; the mere mention of the word extraterrestrial evokes reveries about still unexplored life, displacing the old and once potent exotic that drew earlier generations to remote islands and jungled interiors.” [2]

That Wilson also noted the attraction to extraterrestrial exoticism as an extension of biophilia is significant. Some of us are as intensely interested in life in the universe—the domain of astrobiology—as we are in life on Earth—the domain of life simpliciter. The biocentric-bioscience central projects described above would constitute a search for our “roots” on a more fundamental level—at the level of understanding the place and role of biology in the universe.

Many contemporary visions of the human future, especially since the computer revolution, have been technocentric rather than biocentric. It is a common argument, and perhaps even as common an assumption, that intelligence on cosmological scales of space and time, if any such exists, must be post-biological. The bioscience scenarios for the future of civilization discussed above constitute an alternative to, if not a rejection of, the idea of post-biological intelligence being necessarily or inevitably the focus of emergent complexity for advanced intelligence in the universe.

2. A Missed Opportunity

In the same way that some individual human beings are intensely interested in their genealogical origins, and some scientists are intensely interested in the origins of life—because this is, at the same time, the ultimate origins of human life, and thus the ultimate discovery of our roots—some among us are intensely interested in communicating with peers. In mundane terms, our peers are other persons in other terrestrial cultures. In cosmological terms, our peers are other intelligent progenitor species of civilizations, which have constructed technologies of sufficient power, scale, and complexity to facilitate communication over interstellar distances. And, in the same way that some enjoy the exoticism of other lands and other cultures, the exoticism of other minds evolved on other worlds can be understood as an extension of the same curiosity.

The ten scenarios for future civilization noted above did not account for this particular species of curiosity, and so did not include an obvious possibility, which seems like an oversight now that I think of it in retrospect: SETI as a central project. While SETI as a central project could be placed under the umbrella of science-derived central projects, like the biological scenarios discussed above, it is sufficiently independent that it could also be formulated as a distinctive form of civilization focused on communication, or the attempt at communication, with ETI over interstellar distances.

Adapting the theses that I previously formulated in Space Development Futures for scientific civilization, to the particulars of a SETI civilization, I arrive at the following formulations:

SETI Infrastructure Thesis

A SETI program on a civilizational scale will occur only after a SETI infrastructure buildout makes such a program possible.

SETI Framework Thesis

A SETI program on a civilizational scale will occur after a conceptual framework is formulated that is adequate to motivate the construction of a SETI-capable infrastructure at a scale consistent with such a program.

SETI Buildout Thesis

A SETI-capable civilization makes the transition to a SETI civilization through an institutional buildout that facilitates SETI.

SETI Central Project Thesis

SETI as a central project would be the axis of alignment for all institutions of a SETI civilization, integrating infrastructure and framework into a coherent whole with historical directionality.

Some of these formulations feel more natural than the others, as is to be expected given the historical peculiarities of any civilization; a particular kind of civilization, evolved under particular circumstances, is going to bring out distinctive aspects of the institutional structure of civilization, so that historical contingency drives the appearance of radically different institutions and institutional structures in distinct civilizations, which are in reality quite similar. Some of the institutional peculiarities of a SETI civilization are evident to us even without having an existing instance of a SETI civilization to observe.

An interesting twist that makes a SETI civilization distinct from civilizations dedicated to other central projects is that SETI “success” is not directly dependent upon the scope and scale of the SETI undertaking. Certainly, a larger undertaking is more likely to be successful than a smaller undertaking, and it is a consistent talking point of many SETI researchers that SETI efforts so far have been utterly inadequate to any judgment regarding the existence of ETI and communicating civilizations. [3] However, there is no lawlike proportionality of the scale of SETI efforts and the scale of SETI success; the two may be decoupled.

A given civilization might have a very marginal SETI community (i.e., a civilization that does not take SETI as its central project), using only minimal resources and technology, and still be successful in its search if it were to receive a signal communicated over interstellar distances. [4] A civilization might also make SETI central to its identity, expending resources at the scale of civilization on the search, and still find nothing. The former is not a SETI civilization and yet achieves “success”; the latter is a SETI civilization and does not achieve success. The difference lies not in the success of the SETI enterprise, but in the relationship of SETI to the institutions of civilization. [5]

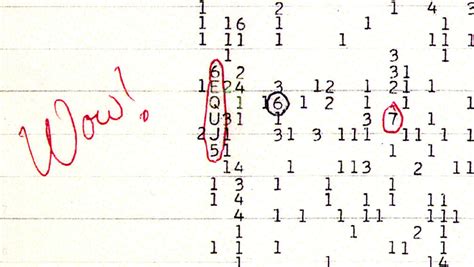

Elsewhere I have made the claim that, had our galaxy been filled with SETI signals from the millions of civilizations postulated in the more permissive scenarios of ETI, the first time a radio telescope had been switched on, it would have been deluged by a riot of signals, and the history of civilization at that time would have been sharply realigned as a result of such a discovery. We would have spent the subsequent decades understanding and interpreting these signals, while there would have been a race to build the best radio telescope that could capture the most valuable signals. We could formulate this as a thought experiment based on several different assumptions, for example:

1) An apparatus is constructed that unintentionally functions as a radio telescope, receiving signals that are ignored because they are not understood.

2) A radio telescope is constructed with no anticipation of the possibility of receiving signals from other worlds, so that once the signals are received, time is required to understand what the signals are and what their significance is. [6]

3) A radio telescope is constructed in a social milieu in which at least the idea is present of intelligence on other worlds, so that the signals are immediately or soon understood for what they are, and the work of interpretation can begin immediately.

4) A radio telescope is constructed with the anticipation of focusing on a SETI, so that the entire effort (i.e., the design, construction, and operation of the radiotelescope) is predicated upon the SETI paradigm explicitly pursued, and signals received are immediately interpreted in this context.

Civilizations in the early stages of their technological development might follow any one of these paths (depending on the universe in which they evolve, the Drake equation N of which is independent of any given civilization), and the outcome for a given civilization would be quite different depending upon the path followed. [7] It would be an interesting thought experiment to elaborate scenarios (1) and (2) above, which are, for us, counterfactuals, as our conceptual framework already encompasses the possibility of SETI signals. Scenarios (3) and (4) above may still play out, such that if radiotelescopes constructed as part of the VLBI network received a SETI signal this would constitute scenario (3), while if the SETI Institute’s Allen Telescope Array receives a SETI signal this could constitute scenario (4)

3. The SETI Paradigm

In an earlier Centauri Dreams post, Stagnant Supercivilizations and Interstellar Travel, I described what I called the SETI paradigm, which consists of several closely related assumptions about the development of civilization in a cosmological context, which assumptions all point to civilizations being largely confined to their homeworld, not expanding beyond their planetary system of origin to any significant extent, and thus converging upon communication with any other civilizations as the only possibility of contact and exchange between worlds. [8]

The fundamental assumptions of the SETI paradigm [9] could be made explicit as follows:

1. Other intelligent beings possessing advanced technology may exist.

2. Interstellar travel is difficult to the point of near impossibility or outright impossible.

3. It is pointless to expend resources on attempts at interstellar travel, and equally pointless to search for signs of interstellar travel by other intelligent beings possessing technology.

4. Interstellar communication is possible by radio, and perhaps also by other technological means.

5. Interstellar communication by radio is the preferred method (or the exclusive method) of contact between civilizations separated by interstellar distances.

6. Resources for communication with other intelligent beings should be directed into either the search for technosignatures (listening), or the production of beacons (transmitting), or both.

7. Other intelligent beings possessing advanced technology may have transmitted information or constructed beacons, either of which we might detect if we conduct SETI research.

8. Other intelligent beings possessing advanced technology may be searching for technosignatures, and in so doing they may discover ours.

I am here using “SETI” as an umbrella term to cover many activities that might be distinguished in a more fine-grained account. SETI is sometimes narrowly construed to mean only radio SETI, but the search for optical beacons and the IR signatures of Dyson spheres are special cases of the EM spectrum, which includes optical, IR, and radio wavelengths. SETI can be understood as falling under an umbrella of related ideas such as CETI (communication with extraterrestrial intelligence, an acronym no longer widely in use) and SETA (search for extraterrestrial artifacts). Insofar as SETI is understood to be the search for technosignatures, the many possible technosignatures all constitute distinct modalities of search, each with its own scientific instruments and its own observational protocols. [10]

In addition to the modalities of technosignature searches [11], there is also the form of interest that a given civilization demonstrates in SETI. There are four broad classes:

1. A civilization capable of transmitting or listening, but does neither

2. A civilization that listens only without transmitting

3. A civilization that transmits only but does not listen

4. A civilization that both listens and transmits

The first, the null case, is not a SETI civilization; the following three possibilities could be the basis of a SETI civilization, and in a fine-grained account each of these three possibilities could hold for any permutations of the modalities of technosignature sources. [12] SETI civilizations are not one, but many—civilizations that take SETI as a central project constitute a class of possible civilizations, any one of which could exemplify the theses of a SETI civilization as formulated above. How we go about defining the possible taxonomies of SETI civilizations and the modalities of technosignatures determine the possible permutations that would make up the members of the class of SETI civilizations.

4. Space Development of SETI Civilizations

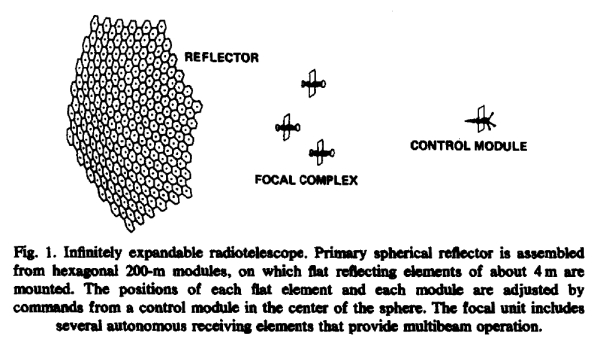

There have already been several papers that outline space development that prioritizes SETI missions. Kardashev, et al., in 1998 (“Space Program for SETI”), and Frank Drake in 1999 (“Space Missions for SETI”), wrote papers specifically about space programs configured around SETI goals. Moreover, some twenty years prior, Kardashev, et al., published “An Infinitely Expandable Space Radiotelescope,” which described a modular radiotelescope constructed in Earth orbit, to which modules could be continuously added, expanding its capacity over time, and thus its functionality (pictured above). Bracewell’s conception of a now-eponymous Bracewell probe (Bracewell, R. N. 1960. Communications from Superior Galactic Communities. Nature, 186(4726), 670-671) is another conception of a space mission configured around SETI goals.

The Kardashev, et al., paper suggests a three step process of building from the more certain and the less spectacular, to the less certain and the more spectacular:

1. investigation of conditions for the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI);

2. search for astroengineering activity;

3. search for communication signals.

The Drake paper approaches the problem differently, advocating radiotelescopes constructed progressively farther out in the solar system from Earth, and eventually using the sun as a gravitational lens for observations. Both of these measured programs converging on more ambitious goals stand within the SETI paradigm and involve no more space development than can occur within our solar system. In Space Development Futures I distinguished a range of space development buildouts from minimal to maximal, and the same can be done for the space development of SETI civilizations, and indeed has already been done in these papers, from a minimal development of investigating conditions for the existence of ETI and building radiotelescopes in LEO, to more elaborate searches and using the sun as a gravitational lens.

The presupposition of the SETI paradigm that interstellar travel is difficult to the point of near impossibility does not necessary exclude spacefaring within a species’ home planetary system, so that SETI space development programs could range through the possibilities explored by Kardashev and Drake, with Drake’s gravitational lens putting spacefaring activities out to 550 AU, which is outside the solar system proper (the radius of the heliosphere is today judged to be about 120 AU, but this is a developing area of research and this radius estimate is likely to change as additional data are acquired). A successful mission to the focal point of the sun, already well into interstellar space, would suggest the possibility of constructing Bracewell probes, which would extend SETI space development to interstellar missions, albeit not for human beings, but only for automated probes (at least at first); the kind of technology and engineering that would make possible a successful mission to the focal point of the sun would also make possible a Bracewell probe, so that the two programs are at least loosely coupled in terms of technological capability.

Implicitly, the idea of SETI as a central project is in the background of Kardashev’s conception of supercivilizations and Sagan’s conception of the Encyclopedia Galactica. Kardashev’s civilization types imply increasing degrees of space development that would allow for ever greater energies to be channeled into detection and transmission of SETI signals. Kardashev makes this explicit in his classic paper of 1964, with type I civilizations being difficult to detect and hard pressed to effectively transmit, while higher civilization types would be easier to detect and more effective in transmission. [13] A SETI civilization, then, might range in space development from some scientific instruments placed in space to a cosmos-spanning civilization that has effectively wired the universe for surveillance and communications. [14]

In Space Development Futures I emphasized that the scenarios described were all indifferently spacefaring civilizations, meaning that these civilizations were space-capable or spacefaring, not properly spacefaring civilizations as they did not have spacefaring as their central project. SETI civilizations as discussed above are similarly conceived as space-capable and indifferently spacefaring. Again, as with the other scenarios, on the way to becoming a mature SETI civilization, the scenario of a robust buildout of scientific instrumentation and transmission capability a civilization might transition to a properly spacefaring civilization, especially when the SETI project flags even while spacefaring capacity grows and distant worlds beckon.

5. The First Edition of Encyclopedia Galactica: The Null Catalogue

The history of the universe to date—much of it unknown to us—has already determined whether we exist in a cosmos populated with biosignatures and technosignature that we will eventually find, or not. Our little slice of time in cosmological history (a slice of time that I call the Snapshot Effect) is what it is, and our searching or not searching will not change this. A typical mammalian species endures for a million years or so. We are not a typical mammalian species, but as an outlier we cannot expect to remain unchanged; the same human intellect that could potentially preserve the viability of our species beyond its natural term could also potentially transform both our bodies and our minds into something unrecognizable.

The future epochs of the universe that we will not know (i.e., that humanity-as-we-know-it will not know) may be as full or as empty as our current epoch, but however populated or lonely, we will not be there to see it, and our civilization (civilization-as-we-know-it) will not be the civilization that apprehends this future epoch. Humanity-as-we-know-it and civilization-as-we-know-it have this present snapshot of cosmological time, and no other. Our account of the universe, our Encyclopedia Galactica (the edition that we author), must reflect this.

If we find ourselves in a lonely and unpopulated epoch in the history of the universe, there is still an Encyclopedia Galactica to be written about the history of the universe to date, but the Encyclopedia Galactica of an unpopulated or sparsely populated universe would necessarily be different from that of a populated universe. It would still be possible to compile a catalog of SETI searches in a silent universe, albeit searches with a negative result. Some SETI researchers have discussed the hesitancy to publish negative results [15], recognizing that these are valuable in themselves and the results are at risk of being lost if they are not published. While disappointing, negative technosignature searches could be the basis of the earliest Encyclopedia Galactica transmitted in our universe.

Such a catalog of the absence of technosignatures—transmitting an Encyclopedia Galactica of negative technosignature searches—would need to be formulated in such a way that, if received by another civilization, they would be able to decipher the stars and planetary systems that were the objects of unsuccessful technosignature searches, as well as the era in the history of the universe during which these searches were conducted. Reference to distinctive pulsars, as on both the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager Golden Record, can triangulate location, and any change in the rate of the pulsars can be used to determine the time of the observation.

A catalog of observations, with the point of origin of the observation (in both space and time) being precisely reconstructable, would be interesting in itself, both for establishing an observational history of the universe, and possibility also helpful in detecting technosignatures. It has been suggested that disappearing stars are a possible technosignature [16], so that a detailed star map from some time in the past compared to a contemporaneous star map could reveal stars that have disappeared from view. Also, indicating red giants in a star map would also be useful, as stars do not remain in their red giant stage for long periods of time in cosmological terms. A civilization receiving a transmission that identified stars in their red giant stage may be able to identify these former red giants with supernovae remnants in their own time.

A galaxy, or the universe entire, might pass through definite stages of the development of civilizations capable of transmitting or receiving technosignatures and collating an Encyclopedia Galactica from these efforts, which would then correspond with successive editions of the Encyclopedia Galactica, something like as follows:

0. The Silent Era—The era in the history of our universe before any technosignatures are transmitted or received.

1. The Lonely Era—The era in the history of our universe in which one or a small number of isolated civilizations record negative technosignature searches and transmit a catalog of the Lonely Era, the first edition of the Encyclopedia Galactica.

2. The Inflection Era—Second generation civilizations in our universe receive the null catalog of technosignatures, and can add to it themselves and the transmitting civilization, expanding the catalog beyond merely negative technosignature reports, thus constituting an inflection point in the development of the Encyclopedia Galactica.

3. The Crowded Era—Multiple formulations of the Encyclopedia Galactica exist, in varying degrees of completeness, and are shared throughout the universe, now crowded with civilizations and the Encyclopedia Galactica editions that describe them.

4. The Terminal Era—As civilization formation slows and eventually ceases, novel technosignatures tail off, and formulations of the Encyclopedia Galactica approach completeness.

5. The Second Silent Era—As the final transmitters sending out a complete compilation of the Encyclopedia Galactica for the known universe one by one fall offline, or pass beyond the cosmological horizon, the universe eventually goes radio silent again, and a Second Silent Era reigns until proton decay or heat death. If any intelligence survives in the universe, it could compile an account of disappearing transmitters that would constitute the final appendix to the Encyclopedia Galactica.

There is also another sense of the Encyclopedia Galactica in which the Encyclopedia Galactica is to be identified with this entire process of cataloging the universe throughout the period of its development when conscious observers are present to render an account of it. Our temporal snapshot of the universe includes the observational pillars of the big bang and so places us relatively near in time to the origin of our universe, allowing us to give at least a limited account of the origins of the universe up to the present day. Other observers may be able to recount later stages in the development of the universe, when these observational pillars of big bang cosmology are no longer visible, but other phenomena are visible.

In the period following what Krauss and Sherrer called the “end of cosmology,” the observable universe will be limited to only the gravitationally bound galaxies of the local group, which will by then all be agglomerated into a single elliptical galaxy. In order to preserve the knowledge of the much more extensive universe visible to us today, our descendants will need the Encyclopedia Galactica as a record of what has been lost from view—including an account of now unobservable technosignatures from other gravitationally bound groups of galaxies.

6. Transformation of SETI in the Light of Technosignature Detection

As noted above in section 2, “SETI ‘success’ is in not directly dependent upon the scope and scale of the SETI undertaking,” that is to say, there is no necessary correlation between SETI efforts and SETI success, insofar as SETI success is defined in terms of technosignature detection (though we can also define success in other ways). [17] Moreover, if a SETI civilization experiences success in the form of a high-information technosignature, it is not clear that it will remain a SETI civilization. What is the endgame is of a SETI civilization?

In the case of detecting a low-information signal like a beacon, this would be a significant source of morale for SETI [18], a suggestion of greater things to come, but in the case of a SETI civilization the SETI project is already the source of morale for the civilization in question. However, it must be admitted that civilizations sometimes flag in their mission, and even a marginal signal detection could prove to rally greater effort toward the SETI mission.

A SETI civilization might not only continue as a SETI civilization after the detection of a beacon, but might redouble its efforts. This, however, merely kicks the can down the road. The redoubled effort is presumably due to a combination of confirmation that ETI is to be found (SETI proof of concept), as well as the continued pursuit of a high-information signal that could prove to be transformative.

Suppose, as a thought experiment, that a civilizational-scale SETI program moves beyond isolated cases of unambiguous technosignature detection, refines its successful techniques for acquiring technosignature signals, and, after the initial excitement and wonder fades, turns to the more mundane task of cataloging technosignatures. Such a catalog would be our own parochial version of the Encyclopedia Galactica (Earth’s Encyclopedia Galactica of the Inflection Era or the Crowded Era, as described in the previous section).

Presumably, if we could do this, some ETI could do this, and perhaps has already done this. Some ETI transmits its catalog of technosignatures, and we discover and decode this signal. Perhaps several ETIs have done this, and we are able to collect and collate multiple parochial Encyclopedia Galacticas, thus producing the most comprehensive Encyclopedia Galatica to date in the history of the universe. Presumably we “pay it forward” by transmitting our Encyclopedia Galactica in its turn. At this point, the task of SETI appears to be complete, leaving nothing for a SETI civilization to do at this point (the Crowded Era implies the Terminal Era).

It is easy to quibble with this scenario. One could argue that new signals might appear with regularity, necessitating supplementary volumes for the Encyclopedia Galactica. One could argue that the transmission of our Encyclopedia Galactica could be carried out indefinitely, and always at higher energies, reaching a greater part of the universe, and moreover that traditional SETI is predicated upon some civilization doing precisely this, that we might hope to receive such a signal. This is one vision of a mature SETI civilization, transformed not by any signal received, but by the imperative to transmit a signal. It does this for as long as it can, until it expires; this is a civilization that has completed its entire historical arc before fading into oblivion (it has fully realized and exhausted its central project).

One also could argue that the one truly transformative signal—the signal that would elevate the SETI enterprise above the cataloguing of technosignatures—was missed earlier in the cataloging process, and, having discovered this later (perhaps buried deep in electronic archives), the true impact on human civilization begins. But note that this transformation of human civilization in receipt of a transformative transmission is the end of SETI civilization and the beginning of another kind of civilization.

Suppose that there is no transformative message to be found among the welter of successful technosignature detections. The work of cataloging continues, and scholars who study technosignatures devote their lives to compiling and deciphering signals, which is a task that converges on completeness the longer it is pursued. Such a dwindling enterprise cannot be the central project of civilization (though it could be the central project of a stagnant and decaying civilization); inevitably, interest will drift to other matters as the SETI task converges on completeness, and some other project will become the central project around which civilization organizes itself, or civilization will fail.

A SETI civilization will not survive its own success. Either it will be transformed by the knowledge gained from a high information technosignature, or the task will become a mundane matter of compiling signals and converging on a complete catalog. In either case, the SETI civilization ends and something else takes its place, but, in converging on making itself irrelevant through success, a SETI civilization must first work through a number of intrinsic internal tensions arising from the nature of the SETI enterprise.

7. Tensions Intrinsic to SETI Civilizations

The impact that a successful technosignature detection would have on civilization, and whether a SETI civilization in receipt of a signal could remain a SETI civilization, is one of many tensions that would play out within a SETI civilization.

Another predictable tension within SETI civilizations would be that between growing efforts on a civilizational scale to detect technosignatures and the growing skepticism that will inevitably follow from the failure to do so. However, the situation is not likely to be so simple. There may be many false positives of technosignature discoveries that temporarily raise hopes, but while these false positives will give a temporary boost to SETI initiatives, the subsequent failure to confirm the signal as an unambiguous technosignature may be dispiriting, and, recalling that these efforts will, in a SETI civilization, be occurring at a civilizational scale, demoralization at a civilizational scale would have severe social consequences. This demoralization problem alone may be sufficiently severe to prevent an authentically SETI civilization from coming into being.

It could well be that SETI undertaken at a civilizational scale may yield a great many ambiguous detections, the interpretation of which becomes a point of conflict. This could prove to be a source of creative tension in times of growth and optimism, while transforming into destructive conflict in times of contraction and pessimism. While a SETI central project is growing and developing, alternative interpretations of ambiguous signals could drive further research, expanding the conceptual framework of SETI, and the dialectic of conflicting interpretations could play out as a synthesis that moves the debate forward. In times of doubt and pessimism, infighting among SETI schools of thought could become rancorous, poisoning the entire atmosphere of the field and thus holding back the development of research, especially retarding the most adventurous ideas, which are the most likely to generate criticism, but which also hold out the hope of the greatest progress.

Another obvious point of conflict will be that between passive and active SETI. Today the “transmission debate” divides the SETI community to a certain extent, and, insofar as in a SETI civilization these issues would be the primary driver of social institutions, the division would reach down into the foundations of civilization. More advanced technological capabilities and more resources available for these technologies will on the one hand exacerbate the active/passive conflict (i.e., the SETI/METI conflict), as a more powerful transmissions will have the ability to reach deeper into and wider across the cosmos, potentially reaching targets not previously reached. On the other hand, as SETI efforts continue, and should they be undertaken on a civilizational scale, but continue to yield no confirmed signals, the case for any signal sources becomes increasingly weaker over time, and the perception of risk declines as the entire SETI enterprise declines.

8. The Success and Failure of Civilizations

Because there is no consensus on a theory of civilization, there is no consensus on what constitutes failure or success for a civilization, and even if we did have a theory of civilization that gained wide acceptance, that still might not be sufficient to judge the success or failure of a civilization. Insofar as any theory would be scientific, it would ideally be value-neutral, and insofar as our judgments of the success or failure of civilizations are freighted with value judgments, the two possibilities of success and failure might not even be addressed by a theory of civilization. However, if we had a theory of civilization, then we could additionally formulate a theory that stood in relation to a science of civilization as conservation biology stands in relation to biology, involving norms of the social ecosystem in which civilizations thrive or go extinct; this would imply some minimal standard by which to judge civilizations.

The entire social science of civilizations remains to be formulated, so that we are not yet in a position to frame a theory for the success or failure of civilizations. However, we can explore the parameters of civilizational success and failure through well formulated thought experiments, through which we can elucidate the intuitions that might someday play a foundational role in a science of civilizations. Moreover, SETI civilizations constitute a unique lens for focusing on the problems of civilizational success or failure given the paradoxical nature of SETI civilization in relation to success and failure (as noted above in section 2), i.e., successful technosignature detection does not necessarily correspond to the scope and scale of detection efforts.

Say, for the sake of argument, and the SETI civilization coalesces within the next few hundred years, and continues for a thousand years or more. During that thousand years of reasonably stable civilization given directionality and coherence through its SETI central project, science, technology, and engineering will continue to improve to the point at which it becomes indefensible to maintain the impossibility or undesirability of human exploration of the universe. These developments call into question fundamental assumptions of the SETI paradigm. Nevertheless, such a civilization, already dedicated to the exploration of the universe, continues this exploration, although now the techniques of biosignature and technosignature detection are supplemented by actual exploration, first by robotic probes and later by human missions. Is this still a SETI civilization? It is still a civilization that is seeking life and intelligence in the universe, and it has even added to its modalities of exploration, though it has arguably abandoned the SETI paradigm.

Let us extrapolate from this baseline scenario of expanding SETI capabilities over thousand year timeline, with a civilization that not only searches, but also transmits. Say a SETI civilization transmits to the universe at large for a million years, or even for a billion years. Further suppose that this SETI civilization goes extinct, and subsequent civilizations determine by exhaustive survey that there were no other civilizations to contact through such METI transmissions, so that the entire effort was in vain. On the one hand, the earlier civilization fulfilled its central project; on the other hand, its central project was predicated upon a false understanding of the nature of the cosmos. Are we to judge this earlier civilization as a success or as a failure?

Both of these two scenarios involve our civilization continuing to search the universe for signs of life and intelligence, but finding little or nothing. “Unsuccessful” SETI, i.e., ongoing SETI without the detection of an unambiguous technosignature, must, over cosmological scales of time, converge on a null result. At what point in the search do we acknowledge that we are probably alone in the universe? And if we have in the meantime built a SETI-centered civilization, what do we do next when we are relentlessly closing in on a null result? In what direction can a SETI civilization pivot as SETI becomes less meaningful? This really isn’t a difficult question. It seems obvious that marshalling a civilization to search the universe for technosignature would, at the same time, involve the search for biosignatures, and a civilization optimized for search and exploration can take the next step through other forms of exploration that would break with the SETI paradigm, but which would nevertheless constitute a natural extension of the activities of a SETI civilization, as in the first scenario above.

We can argue that a SETI civilization can be “successful” in terms of possessing a coherent social project that gives meaning and purpose to the peoples whose civilization is based on SETI initiatives, even if that SETI civilization is a failure in terms of detecting an unambiguous technosignature. This would especially seem to be the case with any growing civilization that is pursuing SETI initiatives. Any set of institutions that is used to facilitate stability, coherence, and directionality for a large group of persons over a large geographical area for a long period of time cannot be judged to be an absolute failure, though it may be seen to damn with faint praise when we allow that a civilization performed a valuable social function while denying the validity of the purpose to which it devoted itself. And we may feel queasy about civilizations that, in addition to facilitating stability, coherence, and directionality, also facilitate bloodshed, warfare, and exploitation, but no civilization could function that was not fully a creature of its age, and no age has been free of bloodshed, warfare, and exploitation.

Another thought experiment could be formulated such that a SETI civilization successfully receives and decodes a high information transmission, but is not transformed by the reception. I argued above in section 6 that a SETI civilization would not survive its own success—but what if it does? Would we judge a civilization a success if it were so stagnant, so impervious to change, that it assimilated the knowledge of a high information technosignature in the spirit of nil admirari? Or, contrariwise, would we judge a SETI civilization to be a failure if it were to detect a technosignature, and the consequences of the detection led to social destabilization and the collapse of the SETI civilization?

Thought experiments such as this can be employed to explore our intuitions about what constitutes a failed or a successful civilization, and the explication of these intuitions could in turn inform a theory of civilization. The paradoxical nature of SETI civilization in relation to success and failure (as noted above in section 2) makes such a civilization especially valuable in a theoretical inquiry, in which we seek to expand our conceptual framework by challenging our intuitions with counter-intuitive scenarios.

9. The Civilizational-Cosmological Endgame

The most breathtaking visions of interstellar civilization, as we have seen with the conceptions of Sagan and Kardashev, have been, in effect, SETI civilizations. Insofar as we are inspired by this vision, the future for civilization is boundless. Albert Harrison wrote, “…if a succession of other search strategies gain acceptance, SETI could continue indefinitely,” and, “…it is very unlikely that even in the case of a prolonged absence of a confirmed detection everyone will conclude that we are alone in the universe.” [19] Like science elaborated as the central project of a civilization, SETI offers the prospect of an endless central project that could serve as the focus of a civilization of cosmological scale in space and time.

This is not, however, the only vision for the future of civilization. Dyson’s conception of a civilization so uninterested in communicating its presence that, despite its technological accomplishments, would be detectable only by a passive technosignature of the inevitable waste heat of industrial processes carried out on a cosmological scale, could also be extrapolated indefinitely, but would be indifferent as to whether or not it was alone in the universe. Implicit in the Dysonian conception are later conceptions such as John Smart’s Transcension Hypothesis—intelligence that has forsaken the outer world for the inner world, or the actual world for virtual worlds.

There is a bifurcation in conceptions of the most advanced forms of intelligence that we can imagine at our present state of development: there are conceptions that are extroverted and expansive, and conceptions that are introverted and indifferent to expansion. The former project themselves into the cosmos and define themselves through growth; the latter look inward and ultimately would be defined by density. These forms of civilization—if they are civilization—would have radically different cosmological profiles, and they would, over cosmological scales of time, evolve into distinct presences on a cosmological scale, which, extrapolated to the utmost, and integrated with the fabric of the cosmos, would yield, in each case, a different universe.

The two are not necessarily mutually exclusive, at least for the next several billion years; our universe could eventually consist of expansive civilizations that sweep outward even while introverted civilizations achieve ever higher energy rate densities and, by doing so, effectively cut themselves off from the outside world, as the effective sphere of communications must contract as rates of communication accelerate. Could two such diverse adaptations of intelligence to the conditions of the cosmos engage in any kind of coherent communication? This is a larger question for another time, but the implications of this question are relevant for SETI civilizations.

The rate at which history occurs on Earth already effectively excludes SETI/METI communication as a driving force in civilization, as civilizations develop over time scales of hundreds of years and, at best, endure over time scales of thousands of years. If Project OZMA had found signals from Tau Ceti or Epsilon Eridani, then there would have been the possibility of communications over a time scale of decades, which could have been a formative element in human civilizations. However, not having found signals closer to home, we look for signals from hundreds or thousands of light years’ distance, which would mean communication over hundreds or thousands of years. Since terrestrial civilizations at best endure for thousands of years, any communication between terrestrial civilizations and civilizations thousands of light years distance would be at most one communication cycle; there would be no dialogue. Such communication could be transformative, in the sense of redirecting civilization on a new path, but not in the sense of being an ongoing influence through interaction.

To sum up: if the time scale of some form of interaction exceeds the expected longevity of the entity involved in the interaction, then the processes and events that constitute the history of the entity in question cannot be constituted by this means of interaction, though this history may be inflected by such an interaction. The rate at which human history develops (and therefore the rate at which civilizations form), which is in turn derived from the rate at which human beings interact socially (i.e., the rate of human conscious interaction), defines certain parameters of history, and therefore of civilization, such that rates that fall outside these parameters, whether above or below the parameters of the relevant rate of interaction, fall outside our purview. The temporal parameters defined by human consciousness and social interaction define in turn our slice of cosmological time (mentioned above in section 5); this Snapshot Effect defines both civilization-as-we-know-it and humanity-as-we-know-it. [20]

Notes

[1] I know of at least two individuals, Claudius Gros and Michael Mautner, who have explicitly advocated such a biocentric vision of the future of terrestrial civilization. Informally, many individuals have expressed to me their interest in propagating terrestrial life beyond Earth as a central motivation for human expansion into space. Cf. the following papers, inter alia:

Gros, C. (2016). “Developing ecospheres on transiently habitable planets: the genesis project.” Astrophysics and Space Science, 361(10). doi:10.1007/s10509-016-2911-0

Mautner, M. N. (2009). “Life-Centered Ethics, and the Human Future in Space.” Bioethics, 23(8), 433-440. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00688.x

[2] Wilson, E. O., Biophilia: the Human Bond with Other Species, Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2003, p. 1. We could also attribute human interest in our own biology to simple anthropocentrism, which can be informally expressed as, “…the endless fascination of us humans with ourselves,” (David Quammen, The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life, section 61, p. 274)

[3] I call this the “drop in the bucket” argument, as it is often stated that our SETI efforts today are a mere drop in the bucket compared to the size of the universe.

[4] This scenario could be used to illustrate the Buildout Thesis. For example, a scientific civilization might build a significant radio telescope infrastructure for the purposes of astronomy, and if astronomical observations accidentally capture a SETI signal, such a civilization might be transformed by that unexpected observation into a SETI civilization. The infrastructure buildout that would make a SETI civilization possible has already occurred; when the transformation occurs, the pre-adpated infrastructure is exapted for different purposes.

[5] The paper “Positive consequences of SETI before detection” (1998) by A. Tough discusses six ways in which SETI impacts society without regard to the detection of an SETI signal. These impacts acting at civilizational scale would shape the institutions of a SETI civilization. Tough outlines these positive consequences as follows:

“(1) Humanity’s self-image: SETI has enlarged our view of ourselves and enhanced our sense of meaning. Increasingly, we feel a kinship with the civilizations whose signals we are trying to detect. (2) A fresh perspective: SETI forces us to think about how extraterrestrials might perceive us. This gives us a fresh perspective on our society’s values, priorities, laws and foibles. (3) Questions: SETI is stimulating thought and discussion about several fundamental questions. (4) Education: some broad-gage educational programs have already been centered around SETI. (5) Tangible spin-offs: in addition to providing jobs for some people, SETI provides various spin-offs, such as search methods, computer software, data, and international scientific cooperation. (6) Future scenarios: SETI will increasingly stimulate us to think carefully about possible detection scenarios and their consequences, about our reply, and generally about the role of extraterrestrial communication in our long-term future.”

These six consequences of SETI, scaled to the dimensions of civilization, would result in distinctive institutions of a SETI civilization.

[6] An historical analogy could be the Holmdel Horn Antenna, which was constructed by Bell Telephone Laboratories in conjunction with Project Echo, as well as to research noise on telephone lines. The Holmdel antenna was not intentionally optimized for discovering the CMBR, but it did detect the CMBR, and Penzias and Wilson initially did not know what they had found until they heard from Bernard F. Burke about the work of Robert H. Dicke and Jim Peebles. Thus Penzias and Wilson were preparing to publish a paper about the unidentified signal they found, not knowing its source, while Peebles was simultaneously preparing to publish a paper that such a signal might be found.

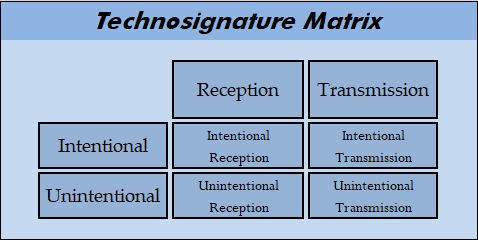

[7] Implicit in these scenarios is a distinction between intentional and unintentional technosignature detection, which suggests a similarly broad distinction between intentional and unintentional technosignature transmission. Laid out as a table, this allows us to construct what I will call the technosignature matrix:

[8] I have recently learned that the phrase “SETI paradigm” has previously been used in the paper “Testing a Claim of Extraterrestrial Technology” (2007) by H. P. Schuch and Allen Tough: “The traditional SETI paradigm holds that extraterrestrial intelligence can be detected from its electromagnetic signature.” However, I have been using this phrase according to the above exposition for several years, so I will continue to use it as I have described; I will note that my usage is not inconsistent with that of Schuch and Tough, though I include additional assumptions.

[9] In his Disturbing the Universe (chapter 19) Freeman Dyson laid out three presuppositions of SETI:

“Many of the people who are interested in searching for extraterrestrial intelligence have come to believe in a doctrine which I call the Philosophical Discourse Dogma, maintaining as an article of faith that the universe is filled with societies engaged in long-range philosophical discourse. The Philosophical Discourse Dogma holds the following truths to be self-evident:

1. Life is abundant in the universe.

2. A significant fraction of the planets on which life exists give rise to intelligent species.

3. A significant fraction of intelligent species transmit messages for our enlightenment.If these statement s are accepted, then it makes sense to concentrate our efforts upon the search for radio messages and to ignore other ways of looking for evidence of intelligence in the universe.”

My list of eight presuppositions of the SETI paradigm is somewhat more detailed that Dyson’s list of three, but I make no claim of mine being exhaustive, or of it being the definitive list; there is often more than one way to analyze concepts into their simple components.

[10] I have noticed recently that Adam Frank has been using “technosignature science” instead of SETI. There is still a kind of stigma attached to SETI (sometimes called “the giggle factor”), and “technosignature science” sounds so much more like serious research than search for extraterrestrial intelligence. Avi Loeb discusses this SETI stigma in his recent book Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth.

[11] A recent paper, “Concepts for future missions to search for technosignatures” (2021), by Hector Socas-Navarro, Jacob Haqq-Misra, Jason T. Wright, Ravi Kopparapu, James Benford, Ross Davis, TechnoClimes 2020 workshop participants, makes an effort to systematically outline what I have here called the modalities of technosignature searches.

[12] If we take Table 1 in (Socas-Navarro, et al., 2021), with its dozen modalites of technosignatures, there are over 8,000 permutations of modalities, which when distributed across the three possibilities of technosignature interest yields more than 24,000 permutations of search that could be the basis of a SETI civilization. Most of these permutations will not be interestingly different from each other, but the sheer number of possibilities points to the many different pathways that a civilization might take and still be within the SETI paradigm (i.e., a member of the class of SETI civilizations).

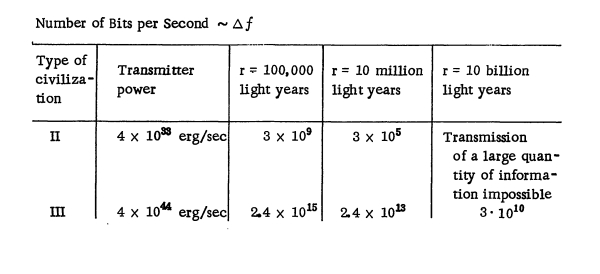

[13] On this Kardashev wrote: “Estimates of the possibility of detecting a type I civilization and related experiments in the ‘OZMA’ project in the USA have revealed the extremely low probably of any such event.” And, “…a type I civilization would be capable of sending a return signal only after its energy consumption had increased measurably.” Kardashev also included a table of estimated bits per second that could be transmitted by type II and type III civilizations.

[14] An imaginative elaboration of the Encyclopedia Galactica idea, which also overlaps with the Bracewell probe idea, can be found in Gerard K. O’Neill’s 2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future, pp. 260-265. In the same way that in a densely populated universe we would have detected a barrage of SETI signals the first time we turned on a radiotelescope, so too if we had lived in a densely populated universe our solar system could be densely populated with something like Bracewell probes. O’Neill notes, “It is possible that there are a thousand probes in the solar system observing us, sent by a thousand, different, independent civilizations—but that every one has been programmed only to observe and never to affect our natural development by signaling us…” (p. 264)

[15] As of writing this I cannot find the quote that I remember about hesitancy to publish negative SETI results, but I did find this: “With a steady stream of refereed, scientific papers carefully documenting negative results from observations conducted by a growing number of research groups in the US and Europe, plus review articles charting the progress of, and potential for, a systematic scientific exploration, the legitimacy of the SETI endeavor gradually enhanced within the scientific community (finally overcoming the stigma of Lowell’s fanciful publications).” Tarter, J. C., Agrawal, A., Ackermann, R., Backus, P., Blair, S. K., Bradford, M. T., … Vakoch, D. (2010). SETI turns 50: five decades of progress in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. Instruments, Methods, and Missions for Astrobiology XIII. doi:10.1117/12.863128 The explicit mention of “carefully documenting negative results” as a hallmark of scientific legitimacy implies by what it does not say that this has often not been the case.

[16] Cf. Villarroel, B., Imaz, I., & Bergstedt, J. (2016). “Our Sky Now and Then: Searches for Lost Stars and Impossible Effects as Probes of Advanced Extra-Terrestrial Civilizations.” The Astronomical Journal, 152(3), 76. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/152/3/76

[17] If METI means merely transmitting a message, regardless of whether it is received and deciphered, then a METI civilization would experience success in proportion to its resources invested in the METI enterprise, but if METI is judged as a success only if a transmitted message is received, then METI success is no more correlated with the scale of the METI effort than SETI success is correlated with the SETI effort. Assuming a decoupling of transmission and reception, METI is a more durable central project than SETI.

[18] “The detection of evidence of another technological civilization will inform us that we are one among many. The immediate tasks of trying to decipher and interpret any encoded information will be tackled in parallel with deciding whether to respond, and expanding the search to find the other technologies we can now be confident are there. Having succeeded with the discovery of one particular type of technosignature, we are probably entitled to assume that this is the standard for communication among all of our cosmic neighbors. A successful detection would mean a reliable source of funding for future explorations and the ability to optimize the demonstrated, successful strategy so that additional detections will take place more rapidly than the first. Embedded information, if any, could also shape continuing searches.” Harp, G. R., Shostak, G. S., Tarter, J., Vakoch, D. A., Deboer, D., & Welch, J. (2012). “Beings on Earth: Is That All There Is?” Proceedings of the IEEE, 100 (Special Centennial Issue), 1700-1717. doi:10.1109/jproc.2012.2189789

[19] Harrison, A. (2009). “The Future of SETI: Finite effort or search without end?” Futures. 41(8).

[20] Humanity exists on a scale of time about two orders of magnitude greater than the scale of time of civilization, but on cosmological scales humanity equally occupies only a snapshot in time.

My issues with the text:

1. Radio is the [current?] best communication technology.

This may or may not be true. Certainly SETI will be conducted based on the technologies that we have. But consider that before the discovery and use of radio, humans had to use other means of communication – smoke/fires, sounds (e.g. drums), semaphores, etc. Early thoughts on METI for Martians was to create a large fire in Siberia with a geometric shape.

We don’t know if there is a better form of communication, but if some FTL communication was possible, ETI would almost certainly be using that, not radio waves. As Clarke said, we might be like islanders listening for distant drumming over the ocean, ignorant of the radiowaves surrounding them.

2. SETI relies on ETI METI

Receiving signals assumes signals are being sent, i.e. ETI is doing METI. Yet the text seems to assume that civilizations do SETI – so who is doing the METI, and why?

3. Encyclopedia Galactica

The described version is rather narrow, more like a catalog of observations over time. Isn’t this really just a more sophisticated catalog?

The more usual assumption of an EG is that it is like a version of our encyclopedias. (Even a simple, truncated version like the Hitchhikers Guide to the Universe). But when has any civilization handed over such a rich source of information to another culture? Religious texts for evangelism, yes. Political books for indoctrination, yes. But has anyone ever given a set of encyclopedias to another culture? I don’t think so, although Britannica might have tried to sell a set to colonials. ;)

A catalog may be useful for the cataloging civilization, but unless it intends to maintain some altruistic METI it won’t help future civilizations.

SETI/METI as a central project

Rather than SETI/METI which might be considered a project for those educated in the humanities, perhaps a more useful central project is searching for life – SETL. Unless ETI is machine/post-biological and widely dispersed via interstellar travel, the lower hanging fruit is the more likely number of worlds harboring life. It will take civilization to be able to initiate interstellar travel by probes at a minimum to do the science on location, perhaps more suited to STEM-focused civilizational projects. Only after advanced life was discovered with some frequency would SETI become a central project, and even then the search may primarily be for artifacts rather than extant civilizations – interstellar archeology that can be started currently for megastructures, but later by probes for buried cities, signs in the geological strata, and other long-lived artifacts in space, like our Apollo LM descent stages on the Moon.

AFAICS, SETI/METI is predicated on human extraversion and the need to “not feel lonely”. We may be better off using our technologies to communicate with terrestrial animals, possibly even uplifting some species. We might also be a lot better off by being more communicative with existing human cultures and encouraging cultural diversity rather than conformity. This will surely be more productive, easier to do, and also exponentially increase the diversity of ideas through cultural interplay. For a more introverted civilization, scientific research might be more than enough to occupy the available resources.

1. I am taking radio SETI as “classic” SETI. A variety of interesting permutations of SETI civilization can be derived by altering, eliminating, or adding to the presuppositions of SETI that I delineated. It seems to be that there is very little deviation from classic SETI by opting for different technologies as the default modality.

2. SETI relies on ETI METI only in the case of our active listening (intentional reception) receiving a signal from active METI (intentional transmission). As noted in my technosignature matrix table, this is one of four permutations. Again, I am relying heavily on the idea of “classic” SETI, while acknowledging that this is not the only possible way of conceptualizing SETI.

3. During the Silent Era and the Lonely Era, the only possible Encyclopedia Galactica is a null catalogue, and, yes, it is just a catalogue of negative technosignature searches, because there is nothing more to report than this and astrophysical phenomena. Certainly the way that Sagan conceptualized the Encyclopedia Galactica was much more elaborate, with some kind of encyclopedia treatment of other civilizations, insofar as they are known. As there are no such known civilizations, we cannot include them. We (or some other civilization of the Lonely Era) could include in our null catalogue an appendix that constitutes a systematic record of our own civilization. Of course, we could also make up a bunch of elaborate entries on civilizations that don’t exist because we wouldn’t want to transmit a null catalogue, but that strikes me as irresponsible. So unless we eventually find a technosignature (or several) or make them up, the only thing we can transmit as our Encyclopedia Galactica would be a null catalogue.

4. Agreed that the search for ET life is lower hanging fruit, and I assume that any technosignature detection effort would be part of a larger effort that would include biosignature detection. If we do make biosignature detections once we have the technological capacity to do exoplanet atmospheric spectroscopy, I assume that our Encyclopedia Galactica would also include these results. Indeed, I should have mentioned this in the above essay. I will include this in future expositions.

Best wishes,

Nick

A very tasty read, Nick. I’m personally a fan of METI and reject the “don’t scream in the jungle” metaphor on the grounds that if this be a jungle, it’s the sparsest collection of trees imaginable.

For a civilisation at our current stage, a relatively quick and cheap beacon could be assembled using the sun. Thin orbiting panels could be arranged so as to provide periodic unary encoding, via occlusion, of the first few prime numbers. Several such (minimally two orthogonal) orbits can be constructed in order to assure omnidirectional signalling.

Thanks! I suspect that there are several designs relatively quick and cheap beacons we could assemble at our present stage of technology. Indeed, it would be interesting to compile a list of possible beacon technologies. A METI civilization would already be building these in its drive to make itself known on a cosmological scale.

Best wishes,

Nick

Don’t even think about it!

There’s a very good reason for Hawkings and others to warn against sending unauthorised signals anywhere. Not only for the reasons we can imagine that any alien civ might have for not having any competition – but the real danger is the reasons they might have for not wishing aliens around that we have not thought about!

But we need not look for exotic psychologies or reasons.

Lets put ourselves in the shoes of a hypothetical alien and ask.

´Is the Hu-mons a potential risk for other intelligences?`

Alien advisor:

´They might develop interstellar capability in less than a kiloannum from now, they experiment with AI and nanotech without safeguards and might cause either an interstellar VanNeumann or grey goo pandemic in even shorter terms. And not only kill and but regularly commit genocide and exterminate varieties of their own kind such as Amerinds, Kameeni, Laplanders….

´Thank you I get the picture, how do they react to other species than their own?`

´They regularity torture intelligent and semi-intelligent species for their amusement or because they simply feel they want to. This include Aves, Bovidae, Mysticeti, Loxodonta ……´

´Quiet! That’s settle it. Hu-mons are definitely a potential threat, have the secretary general give the order that the space based laser system boost the kinetic missiles to 0,9C ASAP.`

So it’s not only that aliens might be a danger to us, our civ is a loose gun and a heck of a danger to anyone else! We need to be very quiet and improve ourselves to quite a degree before we even should consider spilling the beans on our whereabouts.

You’ve been watching The Day the Earth Stood Still. ;) Although I think Isaac Arthur likes the high-fraction of c kinetic planet busters.

@Alex Tolley

Yes it happened to be one ‘Earth stood still’ scenario I did describe. And while it was written in a somewhat whimsical way, it is still a scenario we need to consider. I bet Issac Arthur have covered the subject, he seem to have made videos about nearly every aspect on space exploration and what it might lead to.

No need to bust a planet though, such kinetic missiles would sterilize the target world most efficiently even if the missiles both would transmute and some might disintegrate enroute.

Even the latter ones will still add to the destruction as clusters of heavy cosmic rays. This might also be an issue with the breakthrough starshot sails. Even though those break apart in short order, some world or colony along the line of sight might get hit with remaining high energy particles made up of material of the former probe.

If there actually are a set of other and long lived civs in the galaxy, we should listen and try to find out what they’re up to. So I support SETI, and certainly not METI.

If any optimistic assumption happen to be correct and there is supposed to be lets say 10000 civs in the galaxy, then there must be a “great filter” and we better try to learn what it is first. Instead of behaving like an animal that get attracted to flashes of the fallen down high power line to examine it. *Bzzzzat!*

They are so concerned about human impact on other humans and on non-human species that they destroy everything? That makes no sense. If they are sufficiently concerned they would choose a different solution, perhaps isolation or intervention.

Do intelligent alien species pop into reality fully formed and mature? I highly doubt it. They probably go through their own versions of adolescence and development.

Unless a society is an extreme threat, everyone needs to make mistakes to learn in order to achieve mature and presumably non-threatening adulthood.

So is humanity a “bad” species? Or do we just need time to grow up and appreciate that we are part of a much bigger reality than our one little ball of rock.

And how do we define good and bad? Ask any missionaries of old and they would tell you they were helping to uplift less sophisticated societies. There are no easily defined answers and we need to be very careful not to assume that an alien species evolving in totally different worlds are going to develop along the same lines that we seem to be doing, a big conceit of so many science fiction plots.

Yes, there are reasons to worry about METI. However, it may also be the difference between receiving the “kick” we need to evolve into cosmic citizens or slowly devolving stuck on a single planet while the rest of the galaxy moves ahead.

There is a big difference between safety and stagnation.

Beside my lighthearted previous jokes of a potential ‘godlike’ and holier than you alien race. The fact is that any species that developed trough natural selection will have the traits to attempt getting rid of any competition, both of their own species and others.

It’s built in from the start, if not the selection will work against the species and they go extinct.

As for stagnation, well I agree we see quite a degree of anti-science attitude in this era. The cure is however not to look for any benign angles – sorry read aliens – that would solve all and any problem we got.

The solution is instead better education, and making sure it is available to everyone, regardless of social class or economical background. I am an example of that and such a society where all levels up to a university degree is provided for free also today. If that had not been the case I would have ended up as a manual worker instead of a researcher at a prestigious university doing spearhead research. And I nearly did fail, as the parents had no support to give, and often could not even understand the questions I asked.

So the solution is simple, more education – not less.

I must clarify that I do not necessarily expect or even want aliens to “save” us. Not only might that leave us in a poor position, either being dependent upon them or not learning all that we might along the way on their own, it could also happen that their idea of “help” could be counter to what is best for us, assuming they do not have ulterior motives as it is.

My hope is that by encountering others we might learn from them either directly or through observation and then be able to make up our own minds as to what is best for us as a species and society.

Of course I realize we may have little choice in the matter as to how, when, where, and why we one day encounter ETI. And as the pandemic has taught us the hard way, human reactions are not going to be as a united front.

Andrew, I can’t resist to plug my Dyson Shutter scheme seen toward the end of my co-authored CD article here:

https://centauri-dreams.org/2016/12/21/citizen-seti/

It is time to start looking closer to home…

The Galileo Project for the Systematic Scientific Search for Evidence of Extraterrestrial Technological Artifacts.

https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/galileo/home

Support Us.

The Galileo Project is funded through the generosity of many individual donors. We are unaffiliated with any governmental or military organizations and receive no funding from these sources. If you would like to help support The Galileo Project, we invite you to donate using the following link:

https://community.alumni.harvard.edu/give/16040771

This online giving form, while hosted by Harvard’s alumni platform, is fully open to all interested contributors. To ensure that your gift reaches The Galileo Project, please click on the “Select a Fund” dropdown menu, select OTHER and enter the following text:

Research Fund u/d Professor Avi Loeb

If you are interested in making a gift of an amount exceeding $50,000, Harvard Development will require additional documentation in order to process the contribution. Please contact Professor Avi Loeb at aloeb@cfa.harvard.edu and he will connect you to the Harvard Alumni & Development Services (ADS) at ads@harvard.edu or 617-495-1750.

https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/galileo/fund-us

I consider SETA to be part of the SETI package—one of the many permutations of SETI that might be pursued in combination with other technosignature modalities or alone, as noted in section 4 and note 14 in the above. No one modality of technosignature search need exclude another.

Best wishes,

Nick

What areas in our solar system are the oldest and the stabilist over the billions of years? The areas in Africa that have ancient fossil beds of human remains could there be ancient areas in the solar system where derelict interstellar vessels may have ended up. There are tunnels that let spacecraft go thru an inter solar system highway of least energy use, could there be long term Jupiter trojan ancient interstellar vessels? We need to look at the solar system like Africa and look for the areas/formations that would hold and store the remains of interstellar vehicles. How long would the very high altitude spacecraft around earth survive, GSO would destroy themselves in a short period of time because of collisions, when without human intervention. There are many satellites that orbit in patterns that would not collide with other satellites and may have long lifetimes. Would a probe from somewhere else look in those areas around earth type planets?

Another interesting bit of research that may help both us and other civilizations find habitable planets.

The Milky Way Hasn’t Been Evenly Mixed.

“They found that the abundance of metals varied wildly across the galaxy, with some regions having only 10% of the metal content of the Sun. This means that the gas in our galaxy is not uniformly mixed and that, among other consequences, the formation of planets is not uniform throughout the Milky Way.”

https://www.universetoday.com/152500/the-milky-way-hasnt-been-evenly-mixed/

A messaging civilization can’t broadcast to only one of “your working definition” of a civilization. How would they single out a civilization from that civilizations people? Same applies for any response from the target. Perhaps SETI/METI civilizations must assume the perspective of the people or the meta-civilization when defining success. The SETI/METI central project would by definition include this assumption. If true, the obstacles presented by distance wouldn’t matter.

Innovation doesn’t always require real-time, conscious interaction. A steady stream of data between parties would eventually produce a dialogue as derivative works made their way into the stream. A data stream would drive innovation similarly to libraries and unconscious, natural phenomenon. A real-time, conscious dialogue would always happen locally.

The function of the meta-civilization or the people in the SETI/METI central project may be the crucial element for defining success for such a civilization. The central project is irrational, doesn’t increase the survival odds of the agent, below very generous conditions. To remain rational, the central project may need to describe itself as belonging to a meta-civilazation.

I am not sold on the concept of central projects, but I agree with you. The SETI/METI central project is interesting.

Agreed that innovation doesn’t always require real time interaction, but I would suggest that we could define a continuum from weak interaction to robust interaction, and that SETI in the universe in which communications intelligences are separated by thousands of light years constitutes the weak end of the continuum.

While I would agree that a central project could be irrational, I don’t think it follows that irrationality equates with or entails non-survival behavior. Hume said that reason is and must be the slave of the passions. More recently, a fascinating paper has been written on how cognitive biases may contribute to more robust survival behavior, “Better than Rational: Evolutionary Psychology and the Invisible Hand” by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby (https://www.cep.ucsb.edu/papers/aer94.pdf).

Best wishes,

Nick