If you want to explore the history of generation ships in science fiction, you might start with a story by Don Wilcox. Writing in 1940 for Amazing Stories, Wilcox conceived a slick plot device in his “The Voyage that Lasted 600 Years,” a single individual who comes out of hibernation once every century to see how the rest of the initial crew of 33 is handling their job of keeping the species going. Only room for one hibernation chamber, and this means our man becomes a window into social change aboard the craft. The breakdown he witnesses forces him into drastic action to save the mission.

In a plot twist that anticipates A. E. van Vogt’s far superior “Far Centaurus,” Wilcox has his ragged band finally arrive after many generations at destination, only to find that a faster technology has long ago planted a colony there. Granted, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky had written about generation ships before Wilcox, and in a far more learned way. Fictional precedents like Laurence Manning’s “The Living Galaxy” (Wonder Stories, 1934) and Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker (1937) imagined entire worlds as stellar wanderers, but we can give Wilcox a nod for getting the concept of generations living and dying aboard a constructed craft in front of the public. Heinlein’s “Universe” wouldn’t appear until 1941, and the generation ship was soon to become a science fiction trope.

We can hope that recent winners of the generation ship contest for Project Hyperion have produced designs that avoid the decadence and forgetfulness that accompany so many SF depictions. We do, after all, want a crew to reach destination aware of their history and eager to add to the store of human knowledge. And we have some good people working these issues, scientists such as Andreas Hein, who has been plucky enough to have led Project Hyperion since 2011. Working with the Initiative for Interstellar Studies, Hyperion has announced a contest winner that leverages current technologies and speculates in the best science fiction tradition about how they can be extended.

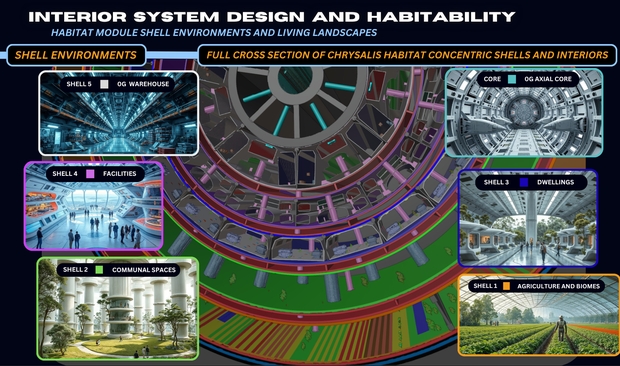

Hein is an energetic visionary, a man who understands that imaginative forays can help us define key issues and sketch out solutions. The winning design is reminiscent of the kind of space habitats Gerard O’Neill advocated, a 58-kilometer multi-layered cylinder dubbed Chrysalis that offers space enough for Earth-like amenities such as grasslands and parks, art galleries and libraries. The notion includes animals, though only as a token of biodiversity in a culinary scene where vegetarianism is the order of the day.

Interstellar Necessities

What intrigues me about the Chrysalis design is that the need for cultural as well as physical survival in a society utterly closed off for centuries is emphasized. Thus Chrysalis offers habitable conditions for 1,000 people plus or minus 500, with care to ensure the handing off of experience and knowledge to future generations, critical both for societal health as well as the maintenance of the ship’s own technologies. This presumes, after all, the kind of closed-loop life support we have yet to prove we can create here on Earth (more on that in a minute). Gravity is provided through rotation of the craft.

Chrysalis is designed around a journey to Proxima Centauri, with the goal of entering into orbit around Proxima b in some 400 years. And here we hit an immediate caveat. Absent any practical means of propelling something of this magnitude to another star at present (much less of building it in the first place), the generation ship designers have no choice but to fall back on extrapolation. As in the tradition of hard science fiction, the idea is to stick rigorously within the realm of known physics while speculating on technologies that could one day prove feasible. This is not intended as a criticism; it’s just a reminder of how speculative the Chrysalis design is given that I keep seeing that 400 year figure mentioned in press coverage of the contest. We might well have said 600. Or 4,000. Or 40,000.

Image: Chrysalis, the Project Hyperion winner. Credit: Project Hyperion/i4IS.

Like the British Interplanetary Society’s Daedalus starship, Chrysalis is envisioned as using deuterium and helium-3 to power up its fusion engines, with onboard power also fed by fusion generators within the ship. The goal is 0.01C with 0.1G acceleration during the acceleration phase and deceleration phase. As to cruise, we learn this about the fusion power sources that will prove crucial:

All Chrysalis power generators consist of toroidal nuclear fusion reactors housed in the hull frame structure and the habitat axial frame structure separating the various stages. The multiple redundancy of the generators for each shell and each stage guarantees a high tolerance to failure in the event of the failure of one or more reactors. The D and He3 liquid propellant is contained in the propellant tank units located in the forward and after interface propellant bays of the habitat module…

Inside Chrysalis

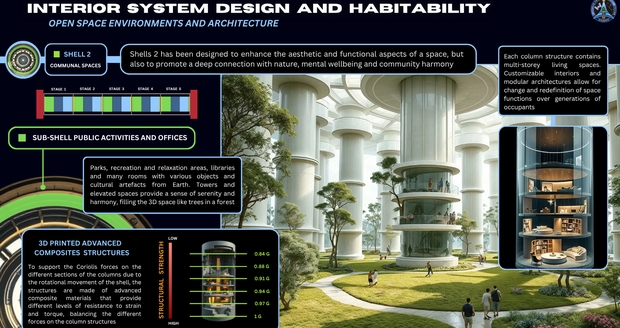

What would it be like to live aboard a generation starship? The Chrysalis report is stuffed with images and ideas. I like the concept of structures designed around capturing what the team calls ‘generational memories.’ These appear to be tall, massive cylinders designed around what can only be called the aesthetics of worldship travel. Thus:

Each treelike structure hosts multi-story and multi-purpose environments [such] as halls, meeting rooms, and other kinds of infrastructure used by all the inhabitants as collective spaces. There are enough of these public environments to have redundant spaces and also to allow each generation to leave a mark on creation (paintings, sculptures, decorations, etc) for future generations…

The Chrysalis slide show makes it tricky to capture the extensive interior design in a blog format like this, but I advocate paging through it so you can blow the imagery up for a closer look at the included text. As with some of the O’Neill concepts, there is an almost idyllic feel to some of these vistas. Chrysalis is divided into five sections, and within each section there are levels that rotate to provide artificial gravity. The report refers to Chrysalis as a ‘biome ark,’ saying that within each stage there are two shells for dedicated biomes and one for agricultural food production.

Here, of course, we run into a key problem (and readers of Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel Aurora (2015) certainly get a taste of this conundrum). Let me quote the Chrysalis report, which describes ‘controlled ecological bio-regenerative life support systems (CEBLSS)’:

Through a controlled ecological BLSS all chemicals are recycled and reused in a closed loop ecosystem together with a circular bio-economy system in which all organic wastes from the living environments are reintroduced and composted in the agricultural soils.

The acronym nudges the idea into credibility, for we tend to use acronyms on things we’ve pinned down and specified. But the fact is that closed-loop life support is as big a problem as propulsion when it comes to crafting a ship made to sustain human beings for perhaps thousands of years. The Soviet BIOS-1 and subsequent BIOS projects made extensive experiments with human crews, succeeding with full closure for up to 180 days in one run at Krasnoyarsk, while in the U.S., Biosphere 2 ran into serious problems in CO2 and food production. As far as I know, the Chinese Yuegong-1 experiments produced a solid year of closed ecological life support, although I haven’t been able to verify whether this system was 100 percent closed.

Daily Life Between the Stars

So I think we’re making progress, and the Chrysalis report certainly lays out how we might put closed-loop life support to work on the millennial scale. But all this does make me reflect on the fact that we’ve spent most of our energies in interstellar studies trying to work out propulsion, when we’re still in the early days when it comes to onboard ecologies, no matter how beautifully designed. In the same way, we know how to get a payload to Mars, but how to get a healthy crew to the Red Planet and back is still opaque. We need a dedicated orbital facility studying both near and long-term human physiology in space.

The Chrysalis living spaces are made to order as science fiction settings. Interior walls can be functional screens producing panoramic views from Earth environments to overcome the spatial (and psychiatric) limitations of the craft. The inhabitants are given the capability of continually engineering their own living spaces through customizable 3D printing technologies so that the starship itself can be seen as evolving as the crew generations play out their lives. Individuals are provided with parks and gardens to enhance privacy, no small consideration in such a ship. The authors’ slide show goes into considerable detail on ecology and sustainability, social organization and mental health.

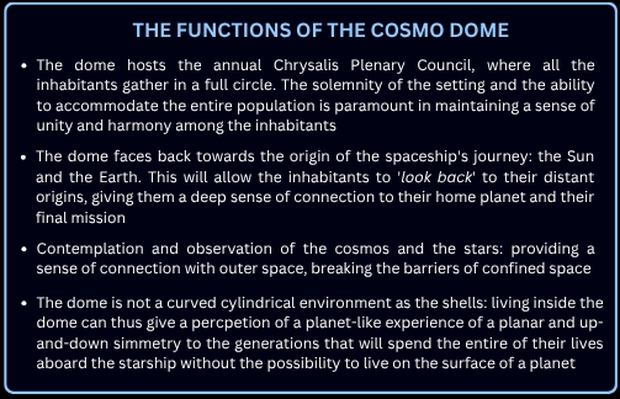

In a lovely touch, the team envisions a ‘Cosmos Dome,’ a giant glassy structure where the plenary council for the mission would transact its business. One gets a goose bump or two here, reminiscent as all this is of, say, the control room in Heinlein’s Orphans of the Sky. Burst in there and you suddenly are reminded of just where you are, with Sol behind and Alpha Centauri ahead.

How exactly to select and train a crew, or maybe I should say ‘initial passenger list,’ for such a mission? The Hyperion team’s forays into sociology are curious and almost seem totalitarian. Consider their Antarctic strategy: Three or four generations of crew will live in experimental biospheres in Antarctica…

…to select and monitor all the characteristics that an interstellar population should have. In addition, the creation of a strong group identity and an almost tribal sense of cooperation among the generations of inhabitants is intended to enhance the inter-generational cooperative attitude of the future Chrysalis starship population.

If I’m reading this correctly, it presupposes people who are willing to consign their entire lives to living in Antarctica so that their descendants several generations along can get a berth on Chrysalis. That’s a pretty tough sell, but it emphasizes how critical the suppression of conflict in a tiny population can be. I’m reminded of John Brunner’s “Lungfish,” which ran in the British SF magazine Science Fantasy in 1957 (thanks to Elizabeth Stanway, whose “Journey of (more than) a Lifetime” covers generation ship fictional history well). Here the descendants have no interest at all in life on a planet. As Brunner says:

These had been children like any other children: noisy, inquisitive, foolhardy, disobedient…. And yet they had grown up into these frighteningly self-reliant people who could run the ship better than the earthborn any time they put their minds to it, and still refused to take the initiative.

Definitely an outcome to be avoided!

Language and Stability

The Chrysalis team describes their crew’s mental stability as being enhanced by many reminders of their home:

Chrysalings will also be able to take walks within the different terrestrial biomes of Shell 1 to be in contact with natural elements and plants of the terrestrial biosphere. In Shell 2 there will be opportunities to do concerts, experience theater activities, access ancient Earth materials (books, art objects, etc.), make crafts and other handmade hobby activities. Shell 2 is the real beating heart of the society, where people come together and can freely co-create new cultures and ideas. Thanks to the use of recyclable materials with which the buildings were constructed, residents can also decide to recreate new architectural forms with different shapes and spaces more suitable to their cultural style.

I think the linguistic notion here is quite a reach, for the team says that to avoid language problems, everyone on board the spacecraft will speak a common initial artificial language “used and improved by the Antarctic generations in order to render it a natural language.” And a nod to Star Trek’s holodeck:

The inhabitants may also occasionally decide to meet in simulated metaverses through a deep integration system for cyberspace…to transcend the physical barriers of the starship and experience through their own twin-avatar new worlds or simulations of life on Earth.

Image: The people behind Chrysalis. Left to right: Giacomo Infelise (architect/designer), Veronica Magli (economist/social innovator), Guido Sbrogio (astrophysicist), Nevenka Martinello (environmental engineer/artist), Federica Chiara Serpe (psychologist). Team Chrysalis.

Anyone developing a science fiction story involving generation ships will want to work through the Chrysalis slide show, as the authors leave few aspects of such a journey untouched. I’ve simply been cherry-picking items that caught my eye out of this extensively developed presentation. If we ever become capable of sending humans and not just instruments to nearby stars, we’ll have to have goals and aspirations firmly fixed, and compelling reasons for sending out an expedition that will have no chance of ever returning. Just defining those issues alone is subject for investigations scientific, medical, biological and philosophical, not to mention the intricate social issues that humans pose in closed environments. Chrysalis pushes the discussion into high relief. Nice work!

Despite a century of scientific and technological progress since the first generation starship was mooted, we humans 1.0 still assume that our apex position in the cognitive realm on Earth means that our meat bodies will be the form our species travels to the stars. With the space colony concept, humans living in Earth-like conditions could be transferred to a starship design, and Project Hyperion maintains that viewpoint. And yet…

Asimov’s robot stories had robots working where humans could not, including testing the first hyperspatial starships. Much later, when retconning the robot universe to the Foundation universe, Asimov presages the issue of why no robots are in his galactic empire. Asimov invokes a conversation between his detective, Baley, and the Auroran chief roboticist, Amadiro, about whether humanoid robots should settle the galaxy first to make it perfect for human settlement. Baley indicates that the flaw is that the humanoid robots will think of themselves as human and resist biological humans from taking over.

But do these human futures make any sense given teh technology trends that are clearly in view today? Why would huge starships like Chrysalis be the first to explore and settle new worlds? The need to bring a large chunk of Earth along shows the problem. Which worlds would be suitable for terraforming to allow human takeover? Can we know in advance without sacrificing humans to find out? In a sense, these living generation ships are the modern version of Noah’s Ark, bringing all the life along that is needed to ensure human survival, to later [partially] terraform an exoplanet like the mountain top appearing as the seas ebb on the flooded Earth. Instead of a mere 40 days, the generation ship needs 250 years before it reaches land after cruising the seas of interstellar space.

We are probably within a century of AGI. Not within the “real soon now” hype of the big AI companies, but also not in the “AGI will never happen” camp. A large disk drive can hold the neural weight matrix of the current frontier AI models, and let’s assume that technology will both increase the size of the models to that of the equivalent of a human brain in architecture and connections. Use that as the template to drive any number of physical robots of any form. The starship needs no biosphere or structure to maintain rotation or radiation shielding. The ship will be far smaller and simpler, needing just the propulsion mass. It may be small enough to have a beamed sail accelerate it to cruise velocity, and its own propulsion to decelerate. Any suitable world can be settled by the ship. The fabrication technology would allow more robot bodies to be built and given independent brains. There should be no competition between any indigenous and terrestrial biologies. No need to prepare a suitable habitat in advance for a human crew. Robots will certainly be damaged and need repair, but the resources to construct new ones, whether inorganic or organic, will be readily available. “Life support” will be little more than attaching an electrical power source.

Any human crewed starship will only arrive much later, if ever. Robots will be our avatars to explore and exploit resources. Given the tools and instruments (or perhaps just their designs for local fabrication), the robots could do all the scientific work we would do.

Terrestrial knowledge and technology will advance while the robotic ship is in transit. That knowledge can be transmitted to the ship, as could newly trained AIs, ready to use it immediately when the mind is embodied.

A machine-based starship, therefore, is smaller and cheaper. Its payload is not burdened by life support, nor the need to ensure stability and a sufficient breeding population to reach the destination. The robotic ship avoids all the problems of maintaining a human environment for the journey. Rather than building a ship that dwarfs the Titanic, a fully outfitted robotic ship may not need to be huge, with the propulsion system chosen being the determining scale factor.

If we must have humans along, if we have AGI-level robots, then we probably can manage to use seed ships, where only the target generation needs to be grown and nurtured to the required age on arrival.

Given the huge scope of the resources needed, not to mention the ethics issues of a generation ship, I find it almost inconceivable that a robotic ship would not be the first to go, and be fast enough to easily keep ahead of any future human-crewed starship using generation ship technology as outlined in this competition.

Just as robotic probes have largely usurped human space exploration of the planets, so robots will be our interstellar explorers.

Interesting design however I think no one is likely to build these multigeneration ships, too many resources required, no one nation would be able to build it alone. Better options would be to put the crew into cryosleep or send robots first however at the end of the day the mission should be to send humans to habitable exoplanets. I’ll be covering these issues including realistic and practical options for interstellar travel here if anyone is interested (LinkedIn article under construction):

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/advanced-propulsion-resources-22-paul-titze-su26c/

Cheers, Paul.

The generation ship is definitely one of the most interesting ideas in speculative science and science fiction. Also one of the less creative, since it doesn’t consider if relativistic ships or sleeper ships or life extension technology would be more practical.

You need a good industrial base with you for tool making.

We got too used to weak little Delta II rockets and the concept of utility fog was born.

You need these grand visions.

It is said that Margaret Meade once remarked that the ultimate purpose of anthropology was not the understanding of existing human cultures, but the ability to devise new ones.

Looking through this material convinces me that the construction of human cultures suitable for interstellar exploration will be much more difficult than solving the problems of propulsion, engineering and navigation.

There are also ethical issues involved here. What if the crew (or their descendants!)

decide at some later time that they want no part of the enterprise? They won’t have the ability to just turn around and come home.

The only analog I can think of for this sort of social engineering is the military. We have spent a great deal of effort programming adolescent men to submit to the rigors of combat, with only limited success. And keep in mind that even that activity is considered temporary by the participants. No one fighting a war is convinced that he will not survive it, or that he will die of old age long before the conflict is decided.

I served on a man-of-war in a combat zone for over a year, and even though I was never in any physical danger or otherwise afraid for my safety, and I truly loved being at sea and the work I was doing, if I had been told I would be doing that for the rest of my life I would have mutinied on the spot.

I can’t think of any voyage in Earth history that would compare with the mission we are discussing here. The only one I can think of that even comes close is the first circumnavigation by Magellan five centuries ago. Only one of his three ships, and less than a score of his initial crew of 270 survived.

Even if it were possible to select and train a crew to do this, and construct a social structure that would keep them together and survive multiple generations, I sincerely doubt we would be able to get it to work the first time we tried it.

Orphans of the Sky was my first leap into interstellar travel, but I had forgotten that it was to Proxima Centauri. “A brief prologue states that after launching in the year 2119, the Proxima Centauri Expedition, the first attempt at interstellar travel, was lost and its fate remains unknown…”

I was also surprised to discover that Heinlein’s novel, Methuselah’s Children, which features a group of people hijacking a starship, served as the inspiration for Paul Kantner’s album “Blows Against the Empire.”

Reminiscient of Clarke’s “The Songs of Forgotten Earth” and Hogan’s “Voyage From Yesteryear”. I agree there’s a lot of work yet to do before a successful robot flyby, an (Expletive) load before seedships can be contemplated and a larger amount than those before a generation ship. Some of those developments may have valuable terrestrial applications.

Gerry O’Neill’s 2nd space book, “2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future,” included using the knowledge of self-sustaining space colonies on Earth. In particular, the idea of city arcologies that circumvent the local climate. We may need such approaches sooner than we think.

While I expect it will prove to be easier and cheaper to put interstellar voyagers into some kind of hibernation (or saved on a disk), there is one huge unwarranted assumption in this article: why do we assume the ship will be culturally isolated?

Sure, they can’t have real-time conversations with people back on Earth, but they can still get transmissions. They will still have access to all of human civilization’s cultural creation during the voyage. A delay of months or years in transmission isn’t very different from the communication lags between European states and their colonies in Earth’s age of sail. Australia didn’t collapse into decadence just because they were getting back issues of the Illustrated London News.

IDK if cultural transmissions from Earth will help. It didn’t help the current nations like Haiti and the Sudan from disintegrating, or the rise of authoritarian governments within the past century.

OTOH, how do isolated remote tribes fare over the long term? Do we know?

This is all fine. But I still think they suck as a concept. Perhaps its because I’m spoiled by living in the Western U.S. However, it might appeal more to people who have grown up in O’Neill style habitats through out the solar system.

Pretty much the same argument that O’Neill and his followers suggested. Space colonies first to build societies, then at some point, some of them would head for the stars.

My bet is that the first humans to become interstellar voyagers will be members of a religion or a cult (a gray area, to be sure) who want to escape the terrestrial (or Solar) authorities to live life their way, or so they hope. Unless FTL or really fast STL propulsion is available by then, they will likely use the generation starship concept to accomplish this.

Religion is historically a strong motivation to want to settle new places, right up their with material exploitation (read money-making schemes). Not only for freedom but also to spread the Word, because those barbaric cultures are just waiting to be “saved”.

The great and mostly hard SF series The Expanse had the LDSS Nauvoo: A huge cylindrical generation ship being built for thousands of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, also known as the Mormons. They wanted to leave the Sol system for Tau Ceti due to oppression from 24th Century human society.

This news item from 2017 on the Nauvoo further highlights the arguments in favor of a religious group making a very long space journey a success. The relevant quoted items which follow come from this link:

https://www.sltrib.com/news/mormon/2017/04/17/a-planet-of-their-own-mormons-spaceship-finally-comes-in-on-tv/

Authors Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck – who are writing “The Expanse” books under the pseudonym James S. A. Corey and are also writers/producers on the TV series – created a tomorrow in which humans have colonized the solar system, but have no faster-than-light ships.

For the purpose of their narrative, they needed a huge ship that would carry a large number of people to a distant solar system – a journey that will take more than a century.

“We wanted to have a generation ship,” Abraham said. “We wanted to have this huge, ambitious, expensive, difficult, dangerous project. We looked around and talked about who would be most likely to get behind something like that.”

They discarded the idea that a government would build such a ship, “because it doesn’t get you any votes,” Franck said. “And I can’t picture a corporation doing it, because there’s no money in it.”

So they kicked around the notion of a religious group undertaking such a project because of “that sort of unity of purpose that’s necessary to invest so much time and energy and treasure into a single project with an uncertain outcome,” Franck said.

The more they thought about it, the more the idea of involving Mormons made sense. Abraham pointed to the Mormons’ trek west to settle the inhospitable Utah desert.

“Neither of us is Mormon,” he said. “But we’ve had enough experience with that faith to see that, yeah, the idea of a journey being baked into the religion, and the kind of underlying sense of radical optimism you’d have to have to undertake something like that seemed like a good fit.”

And Franck came upon news about the construction of City Creek – including that the complex in the heart of Salt Lake City had a $2 billion price tag.

“I was, like, ‘Here’s a group that will drop a couple billion dollars to just have more shopping for people who come to visit the temple,’” Franck said. “And I thought, ‘Well, if you’re building a trillion-dollar spaceship 300 years in the future, who’s going to have the money and the institutional will to do that? It’s the Mormons.’”

For more technical information on the Nauvoo – the series excels at sticking to realistic physics and technology more often than many other science fiction entertainments – see this following article:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/kevinmurnane/2017/03/01/science-and-tech-in-syfys-the-expanse-the-spectacular-launch-of-the-nauvoo/

The makers of The Expanse even delved into the physics of rotating a giant vessel with a “radius of 0.25 kilometers [0.155 mile] and a length of 2 km [1.24 miles]” here:

https://www.wired.com/story/the-physics-of-a-spinning-spacecraft-in-the-expanse/

Here is a video overview of the Nauvoo:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SUebdV7p26g

Here is a fandom background and history of the Nauvoo, where we learn that “the vessel measures 2,460 meters long, with a width of 960 meters,” possesses roughly “a hundred million tons of steel,” and can carry at least seven thousand people onboard, though this number applies to the Nauvoo’s post-generation ship refitting.

https://expanse.fandom.com/wiki/Nauvoo_(TV)

Yep, LJK, as you reference in general, Europeans fleeing religious persecution of course was a fairly substantial contributor to the settlement of British North America. And to the religious diversity of that settlement.

But then religious groups sometimes then would exercise the same intolerance of other religions once they got free of the persecution and got set up here.

All leading to both the Free Exercise Clause and the Establishment Clause in our First Amendment – protecting an individual’s free exercise of their religion but prohibiting state establishment of a particular religion. With all the tension between the two clauses that that entails.

The Mormons would indeed be a good candidate religion for undertaking a generational ship, for the reasons that you note. And as I understand they are preppers like you would not believe – the warehouses with stores of essentials that I saw in a documentary would make you think of a generation ship.

They would have to scale back those big Mormon families during the trip over, however. At least judging by the homes that I see on the market as I’m looking for a place up in Utah.

Either that or devise a replicator that converts energy directly into matter like in the Star Trek universe and build out additional generation ships on the way over to handle the overflow population. Then either bundle them together like strap-on boosters or fly them in formation.

Or they’re going to need a bigger boat from the outset like the line from Jaws, planning that they’re going to grow the shipboard population into the extra space along the way.

But that’s one demographic group for which population decline en route likely wouldn’t be an issue.

Definitely can see polygamy making a doctrinal comeback (Utah statehood basically came at a price) at the destination to quickly boot up the population.

But I did have that same basic thought while reading the Chrysalis society proposal – that they’re trying to replicate the common focus, zeal and ideological stability of an instead religious group.

Not quite sure that a secular group can pull that off without the not-quite-parishioners falling off the path in terms of ideological and behavioral conformity and compliance.

It’s perhaps easier to have unwavering and unquestioning faith in something that you can’t actually see, at least in three-dimensional space, once that initial leap is taken.

Generation ships might be more appealing to East Asians, who are used to living in large, densely populated cities such as Tokyo and Hong Kong. Visiting friends or going on holiday means getting on a space craft to travel from one habitat to another, presumably in the Saturn system. Its kind of like living in Tokyo where you get on a plane and go to Hong Kong or Singapore. These are the kind of people who would live in O’Neill habitats and, later, generation ships to go to the stars.

I have always been fascinated with the concept of generation ships since becoming aware of them thanks to Robert Heinlein and his novel Orphans of the Sky — even though I think they will only be invoked either by people who cannot wait for FTL propulsion or if evacuating Earth and/or the Sol system is required before we have a fast means of interstellar travel.

I also question whether such a project would be allowed to happen at all: If Earth and therefore humanity are in imminent peril, how will the so-called authorities build even one generation ship without mobs of people who know they won’t be on them coming to either destroy the project or force their way onboard, which would also doom the effort?

Will it have to be built in secret somehow, say on the far side of the Moon? Yet would such a thing be possible without an extensive industrial and settlement infrastructure already set in space?

Even if a generation ship is built in a time of relative peace, who will be able to do this and who will get to go? Will the rich and powerful once again get to have it all and leave the rest of us in the dirt?

And where will they go? Will an alien planet as a destination work? Or should they just wander the galaxy, stopping at various star systems to refuel, replenish, and sight see? So many unanswered questions and dilemmas.

This site has links and discussion on various landmark generation ship SF stories, including “The Voyage That Lasted 600 Years” by Don Wilcox…

https://classicsofsciencefiction.com/generation-ships-in-science-fiction/

More here:

https://sciencefictionruminations.com/sci-fi-article-index/list-of-generation-ship-novels-and-short-stories/

https://turingchurch.net/a-history-of-generation-ships-in-science-fiction-e9326388a397

Pretty much the plot and action in “When Worlds Collide”.

Right about the 1951 film version of When Worlds Collide. The only difference from reality I would imagine is that the mob didn’t react in a violent and panicky manner until much later than they probably would have otherwise.

And not just those who had been working on the escape rocket/ark: With all those world-wide catastrophes taking place after the exoplanet Zyra passes close to Earth, I was surprised that desperate surviving mobs from outside did not descend upon the rocket/ark much earlier.

Earlier in When Worlds Collide, there is a dialogue between astronomer Dr. Cole Hendron and business magnate Sydney Stanton where they discuss human nature in times of crisis. As both men hail from very different backgrounds, their perspectives on their fellow humans are equally as opposing…

Sydney Stanton: “What provisions have you made to protect us when the panic starts?”

Dr. Cole Hendron, Astronomer at Cosmos Observatory: “I haven’t thought about it.”

Stanton: “I have. I don’t deal in theories. I deal in realities. Ferris… Ferris!”

Harold Ferris: “Yes, sir.”

Stanton: “Bring in those boxes. I’ve brought enough rifles to stop a small army.”

Dr. Hendron: “There won’t be any panic in this camp.”

Stanton: “Oh, stop theorizing! Once the havoc is over, every mother’s son remaining alive will try to get here and climb aboard our ship!”

Dr. Hendron: “People are more civilized than that. They know only a handful can make the flight.”

Stanton: “You’ve spent too much time in the stars. You don’t know anything about living. The law of the jungle… the human jungle. I do… I’ve spent my life at it! You don’t know what your civilized people will do to cling to life. I do because I know I’d cling if I had to kill to do it. And so will you. We’re the lucky ones… the handful with the chance to reach another world. And we’ll use those guns… YOU’LL use them, Doctor, to keep your only chance to stay alive!”

When the rogue star Bellus is about to strike Earth and the panicked and desperate mobs do attempt to storm the security gates and get themselves aboard the space ark as Stanton predicted, the astronomer agrees with the businessman that he is a better judge of human nature than himself.

Dr. Hendron then heroically gives up his place on the ark, along with an unwilling Stanton, to ensure the vessel will be light enough to make it into space and eventually land on Zyra.

Very intricate proposal. I may follow with more comments, but a few miscellaneous points initially.

I may have missed something related to these points. The format is not conducive to quickly scanning over the whole proposal much less term-searching the whole proposal. At least I don’t know a way to do that, and clicking back and forth and back . . . through 41 fairly intricate slides looking for something specific was labor intensive. And I typically use such full-document means – whole-document scanning and term-searching – to ensure as a final matter that I didn’t miss something on a particular point before commenting. Yes, things are basically grouped topically, but it’s hard to be sure that I haven’t missed something by assuming it wouldn’t be in a particular set of slides addressed to topics that are seemingly unrelated in my mind to the point I’m looking back for.

Subject to that . . .

● Agricultural Redundancy.

If there’s one system that absolutely can’t fail, it’s the agricultural system.

(Well, OK, one of many that absolutely can’t fail.)

I’d split production between two independent agricultural shells. With the production from just one being minimally sufficient in a pinch for baseline survival if the other fails for one reason or another.

Redundancy on critical systems of course should be at a premium in a voyage such as this.

● Some . . . Agricultural Non-Automation.

I see references in the proposal to a lot of robotic automation for agricultural production.

Over and above that being one more thing that can break, hands-on agricultural work would seem to be just the thing to help keep people from going nuts in a confined artificial environment.

And also keep them trained in skills that they may need at the destination.

If they actually make it, they’re going to need to be able to grow crops, etc. even if robotic systems fail. And also adapt their agricultural expertise to the local terrain.

Perhaps AI will be able to do all that for them by then (I remain skeptical). But – as a general overall matter – preserving the capacity for human innovation across those generations may be the most key difference between surviving and not.

The last thing I would want my sustenance to depend on is: “Well, maybe try rebooting the system again.”

● Gravity.

If you’re accelerating/decelerating at 0.1 g, how does that more or less gravitational force interact with the artificial gravitational force supplied from rotating an internal structure?

Does the artificial 1 g from rotation wholly negate or override that otherwise 0.1 g in an orthogonal direction?

Or does that 0.1 g in force at least have some impact on the mechanics and engineering of the rotation infrastructure, as a perturbing force putting an additional tangential mechanical stress on that infrastructure?

And what about the planned 0 g spaces? How does that 0.1 g affect those spaces?

Not my field, so those are my layperson questions du jour.

● Genetic Defects from Inbreeding.

Well, along with these.

After basically eschewing marriage, monogamy, and an explicit family structure in a small population of only 1500, how do they avoid inbreeding and the associated genetic issues as the collective-raised children grow up, hook up, and apparently procreate fairly willy-nilly (subject to population control limits)?

When you look back at early religions, like all those rules in Leviticus in the Old Testament, it looks like a lot of the rules favoring marriage and then also prohibiting people from “laying” with certain other people were designed to prevent inbreeding.

What’s the strategy to prevent that in the social structure they advance? Or are they just accepting the risk of genetic issues along the way? Like with some of those confined communities on Earth where inbreeding occurs basically as a matter of course.

● Looking Forward Rather Than Back.

There’s discussion of employing imagery from life on Earth, albeit likely highly curated imagery given other parts of the proposal tending to essentially isolate and insulate the society from traditional Terran influences, past, present and future. But in any event relying on looking back to Earth imagery as some sort of calming or unifying measure.

If I’m in a big tube permanently heading away from an Earth that I’ll either never see again or for later generations never have seen and never will see, I’m not fully sanguine as to how calming, unifying, etc. abundantly recurring images of life on that Earth will be.

It might be perhaps better to focus more on imaginings of what life will be at the destination. The ultimate why of being in that big tube in the first place.

May just be me, but I’d rather look ahead rather than being constantly reminded of what I or my ancestors left behind and never will see again. While making the current habitat as Earth-like as possible, such as the trees and the like.

Contrast the situation with that of a crew on a long duration mission inside the solar system that eventually will return to Earth. Dreams of home have comforted many a sailor on a long voyage.

But if you’re not ever going home . . . .

George King commented on August 13, 2025 that these proposals, while impressive, are definitely hard to get through easily. Not that the details aren’t impressive or appreciated, but you really need a good outline / summary to show the key points of these plans and what makes them stand out and potentially successful.

I am sorry but those mission statements do not cut it. And Hyperion should point out at the top of their page or make a dedicated one linked to their main page bringing readers in who want the details. I guarantee you that the average viewer will gloss over and skip these proposals due to being so jam-packed with information – some of it in very tiny print.

You also do not want the media outlets distilling these proposals for you. At best they will miss the key points and at worst they will distort the actual information present due to ignorance and their deadlines.

If you really want people to get excited about flying humanity to the stars via this method, you need to present it in a way that will grab and keep them. Then you can get into the nitty-gritty for those who want to know more. Otherwise we will have another one hundred years of pretty graphics presentations on how one day we will fly to Alpha Centauri and beyond – while the public will keep expecting Star Trek warp drives.

I can offer my services as a writer who knows the sciences in this regard, but to be blunt, I do not work for free, nor should anyone.

While I am here, there is this previous Centauri Dreams piece on comparing the building of a generation ship to the construction and purpose of Roman Catholic Cathedrals of Medieval Europe:

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2020/07/17/the-cathedral-and-the-starship-learning-from-the-middle-ages-for-future-long-duration-projects/

There is also this project from almost two decades ago, the Ultimate Project. This plan makes the Hyperion efforts look positively FTL in comparison:

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2008/06/18/the-ultimate-project-to-the-stars/

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2008/02/26/the-ultimate-project-10000-year-journey/

@LJK

From the “The Ultimate Project” post”

With hindsight, this was wishful thinking, given current events.

The projected journey time to reach a habitable planet – 10,000 years or more – is almost as long as recorded human history. A lot can happen in that time, with or without external info dumps on science, technology, and culture.

The time allocated to agricultural activities is quite high, certainly for the adults before age makes it increasingly strenuous.

That was pretty much what O’Neill said if his space colony ag areas failed due to disease. Flush it into space, and restart.

Obviously, the direction of gravity will be a vector, making the forward direction seem a little “uphill”. There is no compensation for this during acceleration and deceleration periods.

As for the dome area, it will experience 0.1g in the wrong direction, so one would need to be strapped down. However, the text seems to indicate it will be used during cruise mode, so the volume under the dome will be at micro-g for most of the voyage.

Starting with those early generation families, with a wide enough genetic pool, there shouldn’t be much problem. The technology on the ship would be sufficient to genetically test each embryo to eliminate known defects, as well as abort any undesirable traits that had been discovered earlier. The ship could make, probably will make, indiscriminate breeding impossible, offering genetic counselling and the ability to make babies a temporary situation to ensure that the population was maintained within constraints. The approach in the TV series “Silo” is an example.

Indeed, “Silo” strikes me as a more likely social scenario, especially the events depicted in Season 2. The generation ship would be much more pleasant to live in.

Alex, I did see that bit about rotating all the adults (subject to age and such) through all the jobs – including agriculture – so that everyone in the small population had the capability to do every job. A very good redundancy concept overall in terms of the human resource itself.

What I was focusing on in the prior comment instead was what those humans then would be doing when they were in the ag unit.

It sounded to me like an “ag” worker then would be in the ag unit overseeing automated robotic systems. Like at a screen, not necessarily so much in the fields doing work that a robot otherwise would be doing.

My point was that those human workers perhaps should to an extent be in the fields doing some of the work that the robots otherwise would do.

Literally hands on. And not merely hands on just a keyboard or a touch screen.

Out actually in the dirt if they have dirt rather than hydroponics.

For one reason to get that “connection with nature” aesthetic to balance out being in a comparatively small artificial environment in deep interstellar space.

And for another to maintain the capacity to actually farm if all that automation failed. Not so much referring to the underlying crops possibly failing from disease. Rather, referring to the automated systems being used to raise those crops failing.

So that if necessary the humans still can be actual farmers – whether en route and/or on the new world – if all that automation goes kaput for one reason or another as the generations come and go. And things break.

I’m not sure exactly how the civilization in the sci fi comedy “Idiocracy” got to that particular state. It’s one of those movies that I’d flip into and out of over lunch if there was absolutely nothing better on.

But I would think one path to the state of affairs in the movie is relying on technology for essential functions – across several generations – so much so that the humans lose the ability to do those functions if the tech goes down. And stays down.

(See also the more high brow movie “Transcendence.”)

So that was what my “reboot” comment was directed to.

Not referring to “rebooting” the ag unit as a whole by venting the whole lot out into space (and my comment was directed also to when they’re on the ground at their destination).

But instead re: being in one of those situations where the tech is down hard, they’ve tried everything to get it back up, and their last gasp at restoring automated functioning is once again rebooting – that – system.

Human hands-on competency here is just an additional, fundamental level of redundancy that also has that “connection with nature” additional benefit. As well as actually the benefits of physical activity, which is critical for sustained long term health, rather than being at a computer screen.

A redundancy sort of like having actual experience doing celestial navigation (as opposed to just reading about the theory of it) when sailing boats – and training one’s next-gen sailor children also to do it – despite the fact that an off-the-shelf GPS unit can provide the same or better location info more quickly and easily.

I’m not a farmer, although I did dabble in growing stuff as a kid (that Southern thing). I’m sure to folks in more ostensibly intellectual pursuits it doesn’t look all that difficult. You stick seeds in the ground, add some fertilizer and water, hang around a bit chewing tobacca’ and voila!, Bob’s your uncle. But I suspect that there a few devils in the details in farming for the actual food that you eat daily. Such that you might want someone with actual hands-on experience, in that dirt, doing it rather than an essentially computer jockey, when what’s at stake is whether you eat or not. Because everything else you relied on previously to produce that food failed.

That’s what my comment was directed to. Over generations you have to anticipate that Murphy’s Law ultimately will apply with full force at precisely the worst possible time, with statistically improbable multiple redundant system failures occurring all at the same time. Including perhaps contamination or loss (from a limited hull breach) also of the dedicated emergency food stores that the society relied upon in the event of having to vent the contents of an ag unit into space.

So I’m a big fan of as many layers of redundancy as possible here, including human farmers with actual hands on experience in the dirt. And two independent ag setups as an additional layer of redundancy over and above maintaining food stores in the event of one ag unit failure.

Especially when we’re talking about the food supply.

What could go wrong?

A whole lot of course over several generations.

(All of which reinforces the advisability of sending robotic missions at the very least first if not exclusively in lieu of human settlement, as you suggest.)

* * * * *

On that 0.1 g force, I also saw what looked to be a long internal circular central corridor – like a long central tube running the length of the ship – that they were using to transport “in 0 g” materials between the sundry units. Sounds like they would then need some sort of mechanism to move those materials through that central corridor as against that 0.1 g. Not a big deal, but something to make provision before before launching and then going “oh, it’s not 0 g all the time.”

And it would seem that an individual would then potentially be able to fall one way or the other down that quite long corridor when they were operating under 0.1 g conditions. So there’s perhaps also a safety issue there to be accounted for in the design.

Or maybe that will become another form of recreation as people free dive the whole length of the ship – like a base jumper – with some sort of safety mechanism if and as needed. (I’m not sure what the force of impact would be from falling all the way the length of the ship at 0.1 g. But it might feel just spooky enough on the way down to be fun.)

Anyway, “may be a while” before anyone is doing that.

@George

By the time this starship is possible, will humans be doing any actual physical agriculture at all? But assuming they have to, I wonder if that would need to be instilled in the test generations. Recall that when Mao’s “Cultural Revolution” put academics on the farms, they fared very poorly.

Garden-level food production is one thing, but managing fields without machinery, and increasingly automated ones at that, will be an increasingly remote experience. Without draught animals, could anyone go back to plowing by hand (assuming ploughing is needed)? Heinlein era “farmers in teh sky” had ICE-powered tractors. Is that technology required at a minimum?

The project assumes that there is a surface habitat ready for the arrival of the generation ship. It must be entirely inhabited by robots; otherwise, why the need for a generation ship to follow? So presumably, robots must work to ensure that agriculture is in place or that it can be initiated upon arrival. To be sure it would work, it would have to be tested to ensure that terrestrial biology would not be harmed by the local environment.

There is also teh question of crops mutating over the journey. Humans have been unnaturally selecting crop traits for thousands of years. We would find some crops remarkably poor from a few hundred years ago. If you want apples, new trees must use grafts to ensure a stable fruit genome. Some evolution will happen anyway, with or without human intervention. The only way to avoid that is by maintaining long-term seed banks. Microorganisms, necessary for food production, will evolve beyond control. Unless the yeasts are to be eliminated, they must remain useful in the generation ship to enjoy fermented drinks. And less the ship is religiously teetotal, you just might need them to ensure safe consumption if the water system becomes contaminated.

Addendum. My food-growing skills are appallingly bad. I wouldn’t last a year having to grow my food if the apocalypse comes. :-(

****

0.1g.

Velocity is proportional to acceleration. So one would fall at 1/10th the speed. Assuming that the central core extends the length of the 5 habitat sections, you would definitely splat at that g when you reached the end. Ending at each section would be too long to allow a freefall. Except that under 1g and 1atmosphere, freefall velocity is about 190 km/h. It would be very much less at 0.1g, so maybe it could be safely done, even without a parachute. Air pressure would likely be the important factor to ensure sufficient drag, although suit design with drag/wing surfaces would be used to make it a “safe” sport. (The kids will want their kicks.) Recall that humans with wings could fly under their own power in 1/6th g. I would imagine that if it had to be used during the 2 acceleration/deceleration phases, there would have to be elevators to move people and things, just as there has to be radially during rotation.

Well, Alex, I believe I’ve encountered my first Brit who wasn’t an avid gardener, at least by inclination, lol.

But . . . if when all the other chips – and technologies – are down, these humans can’t make it just with their hands, in a freaking field (or two or . . .) – as their ancestors did with far less knowledge and resources to work with initially – to feed 1500 people well, they then frankly should be screwed if the automation, etc. fails.

Like a sailboater who transitions from coastal to blue water sailing without learning celestial as a backup.

And keeping themselves intimately involved in agriculture – and not just at a touch screen – will help maintain a working knowledge to deal with things like evolution or mutation of crops, etc. A working knowledge – a human tradition cultivated and handed down over generations – that can be invoked without first having to access tech if that particular tech is part of the tech that goes down.

And, as you have noted, the idea is to develop cross-competencies by all, which would include also the more academically inclined. They’re going to have to get their – uh, head – out of their, uh, (virtual) books in many such capacities. (And I say that with two degrees.) Little red book not required.

(Even with a suitably advanced AI or AGI assist, this is a quite complex overall machine and set of systems for just 1000 adults to keep operational over multiple generations.)

Outside of a possible backstory for that Idiocracy movie, we don’t necessarily have to get in a sense collectively dumber – and lose a most critical life-sustaining capability – while we get more advanced.

Perhaps consider maintaining hands-on, in-the-dirt ag competency analogous to a backward capability to still use a prior legacy system, such as is programmed into a new operating system.

I did see a reference at slide page 15 to raising some animals en route (also a good skill to keep active if feasible). (I do agree that they won’t need to raise animals to eat the animals, as the dietary combination of legumes and grains produces a totally effective protein source including at least all 8 essential amino acids, with no natural meat or artificial protein synthesis required.)

Anyway, maybe they can raise a couple or so bio-engineered horses to pull a plow, although that’s probably more points for style in maintaining competency.

But, one way or another, this is a rather critical function for quite deep levels of redundancy.

Including perhaps engaging in at the very least that most stereotypical of Brit avocations and doing a little gardening.

Alex Tolley said on August 13, 2025 at 15:02…

“The ship could make, probably will make, indiscriminate breeding impossible, offering genetic counselling and the ability to make babies a temporary situation to ensure that the population was maintained within constraints. The approach in the TV series “Silo” is an example.”

As we see every day in examples on Earth going back to prehistory, the only way a generation ship will be able to stop “indiscriminate breeding” among its passengers will be via draconian measures — and such measures will only create an intolerable situation that will likely bring down the whole system. Either that or will we have a bunch of humans who are human in appearance only.

The planners better plan for mistakes and human nature and in ways other than something that would scare George Orwell, or the whole effort will go bust. Am I being too pessimistic? Unlike on Earth, the crew of a generation ship will have far less room to make mistakes.

@LJK

I don’t recall that contraceptives, especially the “pill,” created a problem reducing unwanted babies; quite the reverse. Did China’s “one child law” create dystopia (any more than it has)?

Most Western countries are already below the replacement birth rate in the native population. If anything, the generation ship may have problems ensuring the needed replacement, much like Singapore [a generation ship in all but name?].

What the social situation will be like when a generation is ready to go, I have no idea. But if the world is wealthy and still well populated, a condition needed for its development, then I suspect that there will not be any high birth rates (or death rates) in that society.

I was not thinking of contraceptives so much as the powers that be on a generation ship controlling reproduction via strict laws and even draconian technological methods. People always find ways around these things, which might cause problems for the balance of the vessel and its various support systems. Unless they want to create a race of virtual obedient zombies from the start.

This is one of numerous reasons why I think generation ships should or can only happen if the human species needs to leave the Sol system and no other means of propulsion are available. Otherwise if we are talking about exploration and even settling other star systems via seeds ships, advanced machines will be sufficient.

Unless we want to create human species that are biologically adapted to all sorts of worlds and even outer space itself.

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2022/11/04/in-person-or-proxy-to-mars-and-beyond/

I suppose we could send out many of these large colonies in a stream. If we do then the colonists can move between these colony ships each having a different culture to spice things up, a sort of holiday.

I just paged through the presentation. its definitely more suited for people who’ve grown up in Tokyo or Singapore than someone like myself who grew up in the American west. The artificial parks in the ark even look like Singapore to me (Sentosa Island). Generation ships can more easily be pitched to East Asian societies.

The comment about religious offshoot groups using generation ships to go to the stars makes sense as well. Maybe the Mormons will do this.

Making the world ship completely self sustaining as far a food is concerned is the problem especially for one thousand people. The 600 years to Alpha Centauri is very retro and passe. It’s just too slow and it looks like there might not be any planets there if we include astrometry and radial velocity. A gas giant would not be much help. There is Proxima B which they did not know existed in 1940. There might not be any water or oxygen there so one would have to terriform that place.

If we could have a self sustaining world ship, then why not make it faster and first wait until we find Earth 4.0 with oxygen before we make the trip. I still like the idea of a world ship, but to me it is more of having a self sustaining space station. One wouldn’t have to like one’s whole life in space for that.

@Geoffrey

The Hyperion Project assumes that there is somewhere suitable to go to before it leaves. Interestingly, it pretty much requires a robotic ship to pave the way, either with a terrestrial habitat (on teh surface is presumed) or a planet that is suitable for habitation, i.e., is very Earth-like in almost all ways that allows the crew to live on the world and “integrate” with teh indigenous life, much like Europeans colonizing Africa.

What would seem pointless is if the habitat were just another space habitat, but perhaps on a larger scale, e.g., the size of an O’Neill Island 3.

O’Neill had suggested that his space colony designs, if augmented with huge conical mirrors to concentrate weak sunlight, could be expected to put out to 2-3 light days from the sun, that is, almost out to the start of the solar gravitational focal line of 550AU. That seems very distant from the inner solar system and would be difficult to reach by the authorities. Certainly less reachable than emigrating to a remote island or location on Earth. So why even go to the stars for this freedom, unless the destination is remote, very habitable, and arguably unknown to the authorities on Earth, perhaps with deliberately manipulated information about the exoplanet.

It seems to me that if one wants lots of lebensraum, that varies in biome and culture, like the many different places on Earth, the original idea of building vast numbers of large space habitats in a Dyson swarm makes much more sense. The sheer land surface would be millions of times larger than Earth’s, with potentially far more diversity. Pick your habitat from a catalog to suit your desires. If they change, move to another. Any habitat failure can allow evacuation other other habitats, temporarily or permanently. This would be far safer than a generation ship, and there is no need to spend generations in one vessel, with only the last few generations reaching the “promised land”. Even the Biblical Israelites only spent 40 years wandering in the desert after escaping from Egypt before settling around Mt. Sinai.

The Chrysalis Society

The fault . . . is not in our stars,

But in ourselves . . . .

– Shakespeare’s Cassius, in The Tragedy of Julius Caesar, Act I, Scene II

● “An Interstellar Society.”

By its all but explicit design, the Chrysalis society seeks to break down a human population’s connections with prior Terran culture, structures and institutions – such as even language and otherwise internal familial relationships – and realign their connections instead exclusively with the Chrysalis society. Isolating that population both initially and over the course of succeeding generations from traditional Terran cultural influences.

You see that in multiple different contexts, a number of which I will review in this comment.

But it all starts first here on Earth. In Antarctica.

At slide page 34, the team proposes “partially” isolating the ultimate Chrysalis population in biospheres down in Antarctica for three or four generations “to select and monitor all the characteristics that an interstellar population should have.” Seeking thereby to create “a strong group identity and an almost tribal sense of cooperation among the generations of inhabitants . . . to enhance the inter-generational cooperative attitude of the future Chrysalis population.”

So they’re basically going to put folks in a constrained and controlled – and isolated – environment down in Antarctica for three or four generations and presumably cull out the people who spit the bit.

All to produce that “strong group identity and an almost tribal sense of cooperation among the generations of inhabitants . . . to enhance the inter-generational cooperative attitude.”

Now, if you’re raising – say – sheep across several generations, culling out the noncompliant sheep along the way, you might thereby produce more docile sheep. (Sort of like we probably did back in the day when we first domesticated sheep and other animals.)

I’m not so sure that humans with free will are – or should be – subject to quite the same husbandry.

And even producing a generation of compliant – pardon me, “tribal and cooperative” – humans at launch doesn’t at all guarantee what will happen with succeeding generations of humans with free will.

And in deep interstellar space you can’t cull out the nonconforming humans along the way like you can at least try to do in Antarctica. Well, not unless you’re going to eject – them – into space, too, like a diseased crop.

There of course are numerous sci fi dystopian stories out there about noncompliant humans springing up amidst conformist societies.

Like the quote from the movie, life – and noncompliant, nonconforming free will – always finds a way.

Building a long-term society upon anything else is building upon a foundation of sand. A society premised on conformity and compliance – with an attempt at essentially curating, in truth selectively breeding, humanity over the course of multiple generations – is a fragile, not a stable and robust, society over time.

Nor is it a society that many free-thinking humans would want to be a part of, whether here or in the stars.

● Language.

As a first example, at also slide page 34, the team proposes to adopt – starting in Antarctica – “an initial common artificial language without etno-specific biases” in order “to avoid . . . differences and misunderstandings and translation difficulties.”

Now, in truth, there’s no real need to impose a top-down artificial language on this population.

Just use one existing language – any language – for basic common operations, similar to how “Air English” can be resorted to for international air traffic control.

I don’t care if they adopt Air English or Air Swahili for Chrysalis mission-critical shipboard operations, an instead top-down imposed artificial language is a “solution” looking for a problem in this respect.

Otherwise, much of the world, particularly outside of the United States, and that’s also changing, otherwise is multilingual and functions quite well.

For example, I remember in particular eating at a diner breakfast bar, like a Denny’s, in Laredo, Texas and listening to the multi-ethnic staff communicate with one another and with the multi-ethnic customers fluidly and clearly in both English and Spanish, as necessary and as per just the flow of an overall smoothly bilingual conversation amongst the staff in particular. And it was much the same across the river in Nuevo Laredo.

And it is much the same around the world, especially in multilingual Europe.

Here, too, a top-down imposed artificial language is a “solution” looking for a problem.

To an extent, the spacefarers will develop some form of “ship-speak” naturally anyway, drawing from the sundry languages that they start with. Probably pulling from one language or another particular phrasings that say particular things more easily.

All of that will occur wholly naturally and intuitively, especially with children.

We’ve been doing that since the inception of language, for at least tens of thousands of years, if not much longer.

Language flows on its own, all by itself. And has been for quite some time.

There’s no need to force the issue by artificially concocting a language for day one.

Also, to the extent that the team – supposedly – wants to keep a connection to Terran knowledge, at least starting by keeping the already developed Terran languages that that knowledge base is written in facilitates that goal. Without needing to then translate to – connect – to the past body of – Terran – knowledge, opinion, philosophy, etc., etc.

So in no respect do they actually need to impose an artificially concocted common language.

To me, the “tell” as to what they’re instead seeking to do is that reference to “etno-specific biases” at slide page 34.

The top-down artificial language in truth is just another facet of the overall effort to actually break down “etno-specific” and other connections with Earth and replace them with instead a connection to the Chrysalis society. And only that society.

In a sense, somewhat, like Orwell’s Newspeak in Nineteen Eighty-Four, although Newspeak served also other purposes.

“That kinda’ should be a red flag.”

● “Interference From Earth.”

In that same overall vein, on slide page 39, the team states that “long-term telecommunications contact with Earth and its implications for possible interference with many different aspects of Chrysalis society processes has TBD” which I read as “to be determined.”

Kinda’ thinking that time – and the speed of light – will take care of any such issue to a considerable extent.

But more to the point . . .

Apparently they are at least considering cutting off all communication with Earth from the outset for fear that their so very crystalline social structure – already supposedly “partially” isolated from the rest of Earth in Antarctica for several generations – will fall apart.

That speaks – volumes – as to what “the Chrysalis society” is – all – about.

A society that cannot tolerate outside input is not a free society.

Certainly not a robust one.

“That kinda’ should be a red flag.”

● Interpersonal and Familial Relationships and Child-Rearing

Under the proposal, “[t]he Chrysalis family structure revolves around the identity of each individual and their sense of belonging to the entire starship community.” Slide page 22.

“. . . sense of belonging to the entire starship community.”

Starting to see a trend here?

Of eliminating or at least curtailing all other human connections and replacing them with the – primary – connection instead to the Chrysalis society.

And, yes, there is more.

In the Chrysalis society, “[t]here are not strictly bidirectional mother father and parent son/daughter relationships but all individuals grow in a horizontal and shared community-like family structure.” Id.

Sounds a bit like the elimination of family for instead community child-rearing in Huxley’s so very dystopian Brave New World.

“That kinda’ should be a red flag.”

Now, they do ameliorate that scenario a bit on slide page 38 where they talk about the typical day for a “Chrysaling.”

In that day, an adult in their 30’s begins the day “caring for his or her child.” Well, not every day. The “care of the offspring” [a/k/a their child] is “assigned” in “weekly shifts . . . to the biological father and mother for the first 10 years of life.”

Guess they’ve never grown up being shuttled back and forth from one parent to another in a joint custody arrangement. Or looked at how “well” similarly-raised children grew up over time. (Been there, done that, on both accounts.)

Now, the couple – to the extent that there is such a thing in Chrysalis society – purportedly “can decide to live together but it is not ethically compulsory.” Slide page 22. But it doesn’t sound like something that is – favored – by Chrysalis society Given that the proposal instead proclaims at slide page 38 that while “[o]ccasionally the biological couple spends time together . . . to maintain a broader sense of community within the spacecraft each parent lives individually in [their] own living unit.”

You don’t have to read between the lines to see the societal pressure for the otherwise parents to live apart.

“To maintain a broader sense of community.”

“And you don’t want to do anything that goes against our sense of community, do you?”

“We all have a duty to protect Our Community.”

So, here we are, once again, curtailing other human connections to promote the connection instead to the Chrysalis society.

● Conclusion

And that my friends is how you get to a dystopian at the very least society.

It just doesn’t pop up on its own on a Wednesday morning all by itself, before the first scene in the dystopian sci fi movie starts.

You get there in steps.

And the steps are based on disconnecting and distantiating the individual from all other human and societal traditions, affiliations and connections other than a sole remaining substantial connection only to the then-installed replacement society and/or state.

Leaving only a distantiated and disempowered individual and the society or state.

I may follow up with a note specifically on the explicit structure of Chrysalis political governance.

But, meanwhile, if and when we get to a discussion of a proposed constitution for Mars, once I ultimately submit a finished proposal for editorial review here . . .

. . . I’m going to be making this recurring point.

Tyranny can take many, many forms, not just that of a single authoritarian figure with a short-man complex and a funny mustache.

George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four of course presented a literary example of a totalitarian state.

Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, in contrast, presented a literary example of a totalitarian instead society. Where a compliant and conforming populace for the most part kept itself – including potential nonconforming behaviour within the populace – in check.

It was only when presented with the occasional noncompliant, nonconforming individual that the truly totalitarian nature of that – society – came into focus. A metaphorical hand in the background exercising control and enforcing compliance and conformity was more hidden than in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, but ultimately it was still there all the same. An overall society functionally can be as tyrannical as an explicitly totalitarian state when it comes to nonconformity by individuals.

And I maintain that the Chrysalis society – as conceived and indeed by its very raison d’être – represents such a tyrannical society, regardless of the specifics of its otherwise political structure of governance.

To be sure, this whole generation-ship proposal is just a thought experiment.

Regarding something that is – generations – away at best, if it ever were to be done at all.

But how we visualize human exploration and settlement of the cosmos now potentially resonates into how we as a species will visualize – and structure – such exploration and settlement when we ultimately actually send humans off this world as permanent settlers.

Such as on the Moon.

Or on Mars.

For me, it is vitally important – for the species – that we clearly contemplate humans venturing out into the stars as a free people.

Otherwise, we may as well just send a shipload of sheep out there.

Sending humans to the stars “would be so easy” (well, excepting things like propulsion and sufficiently robust life support systems) if they weren’t so . . . human.

I would rather send – humans – to the stars, with all their perhaps idiosyncrasies and flaws.

Not a prefabbed quite likely in the end dystopian society in a tin can.

Brave New World was a cautionary tale, not an instruction manual.

@George

A similar “experiment” was carried out in the kibbutzes of newly founded Israel. The society was more of a collective, with the children raised without their parents. The approach was not long-standing as traditional family structures returned. However, I don’t think it is a dystopia, at least as practised in the kibbutzes.

You can read a short article on one person’s experience of being raised this way Child of the collective, but there are plenty of academic social studies on this.

Yep, I would expect something similar to have been around in one society or another at one time or another. And at some point I apparently edited out an acknowledgment to that effect when rearranging what I had in draft.

With the key distinction being in this instance “at least as practiced by the kibbutzes.”

My focus as to the Chrysalis society is as to both what they’re doing and why they’re doing it – here specifically to inhibit other human relationships, etc. so as to promote the instead preferred relationship to the society itself. (A jealous mistress as it were.)

Which in both respects dovetails with Brave New World as I recall the storyline and features in that literary work.

Is there any point in building a generation ship? Surely technology would advance in the following years and be able to build a new ship that could easily catch the old one up and get to the destination 1st. Just wait until we have the technology to bend time and space and get anywhere almost instantly. The dangers of a generation ship are just too many even if you put people into cryogenic sleep

SF author Poul Anderson wrote at one point that he no longer believed in the possibility of generation ships. OK as someone who must thought about many speculative issues out of interest and for their potential as science-fiction, he presumably had his reasons. Although he didn’t explain them in detail.

For myself I am surprised no-one else has pointed the one aspect of generation ships that most likely renders them improbable. This is their mass. The generation ship in Expanse cited as having a mass of one hundred million tons. Any propulsion system capable of getting a vessel like the Chryslis to Proxima Centauri in 400 years consume a massive amount of energy. The same amount of energy will send a lower mass vessel there in a far shorter period of time. Possibly, short enough for a manned vessel to make it there and return, perhaps, within a human lifetime (trying not to make it too optimistically short).

Of course, there are alternatives to generation ships. To suggest a variant on an Arthur C Clarke concept. Send an automated vessel to, say, Proxima Centauri, once there robotic systems will manufacture human DNA in form of ova and spermatozoa, fertilise them, artificially gestate them, and raise a new generation of humans who will have been transplanted there who can explore and eventually settle their new home. This assumes improvements in biotechnology, but by the time we can build spacecraft the equivalent of a generation ship it should have been attained.

There are major ethical questions about creating people who have no choice from their birth but to be our surrogates in exploration and interstellar colonisation. However, there are parents who think they have the right to determine the beliefs, attitudes, values and even occupations of their children. We don’t always question that parental imposition.