Millis on The Space Show

Marc Millis is now in Brussels for another TEDx talk — I link here to the TEDx description of him as ‘a rock star in the world of space geeks’ that always gives him a chuckle. More about the talk as soon as I have the link for online viewing. All this reminds me to tell you that Marc and I were guests on David Livingston’s The Space Show last week, with the MP3 now available at David’s site. Although we did kick around some interstellar propulsion concepts, particularly in the call-in segments, we spent most of the time talking about Tau Zero and the 100 Year Starship project. If you want to hear about the nuts and bolts of Tau Zero including the interesting and developing university affiliations, check out the two-hour podcast. David is a superb interviewer.

SF and the Sublime

Gregory Benford recently posted Peter Nicholls’ Big Dumb Objects and Cosmic Enigmas, a talk delivered in 1997 aboard the Queen Mary (now anchored at Long Beach, CA) on his site. Given the number of comments the recent science fiction discussion here has generated, it seems a good time to point to what Nicholls has to say. His ‘big dumb objects’ are vast alien artifacts, and he wants to relate them to what has always been called the ‘sense of wonder,’ a much abused term that describes our reaction to science fictional settings and situations. But let him describe what he’s about:

There is in science fiction, even or especially (as I will argue later) in so-called Hard science fiction, something which in other context we tend to think of as unscientific, be it called sense of wonder, or the sublime, or the transcendent as the Panshins have it, or the romantic. And one rather mechanical way of creating this effect is for the storyteller to imagine something very very big and mysterious, like the spaceship Rama, or like Larry Niven’s Ringworld. That is, the mysterious something in science fiction often has its locus classicus in the Big Dumb Object.

Now you can think of a lot of science fiction that fits this description, and Nicholls treats many of these titles, enough to give you a good holiday reading list and more. Gregory Benford’s Galactic Centre series is here, along with Bob Shaw’s Orbitsville and James Blish’s Cities in Flight. From Greg Bear (Eon, Eternity, Legacy) through Paul McAuley (Eternal Light) and Charles Sheffield (Summertide), he explores the tension between the familiar and the deeply strange ‘otherness’ of these tales, which becomes a kind of transcendence that transports the reader and opens up new ways of seeing the world. In the passage below, he contrasts his own reaction to such works with that of fellow editor John Clute, who worked with him on The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (2nd ed., 1993 and now available in a beta 3rd edition online):

So we’re reaching a more sophisticated view of what space fiction in general and BDO fiction in particular tends to be about. It is about being dwarfed by space and hugeness, about attempting to maintain our own humanity, warts and all, in the light of this vastness, while at the same time yearning to be better or other than what we are. And this is not a theme that is intrinsically scientific at all, which makes it all the odder that it is in the hardest and most scientific sf that we tend to find the purest examples. I believe that what drives some of us to be scientists in the first place is an unusual openness to the sort of experience-or perhaps I should say the sort of feeling-that I’m clumsily and not very successfully trying to pin down. My own training is in both the sciences and the arts, though I should say the scientific bit in its formal manifestation was a long time ago. John Clute’s training is in the arts only. I’ve wondered at times whether my greater sympathy for certain kinds of science fiction, and my lesser sympathy for some other kinds, might not be a result of this early imprinting. I probably exaggerate.

I had never encountered Nicholls’ essay before and I commend it to you. He sees the writers of hard science fiction as not less but more romantic than their colleagues in ‘softer’ science fiction, finding the romantic element in the metaphors of deep space, which include the alien artifacts under consideration here. It’s certainly true that ‘big dumb objects’ — here I’m thinking specifically of Larry Niven’s star-encircling Ringworld, can so rattle our preconceptions that they do evoke that sense of the sublime that early 19th century writers and artists found in places like the Alps. Science fiction is not our only ticket to transcendence but the best of it does evoke the enigma of contact with things so far beyond ourselves that they partake equally of science and art.

Stormy Times on Saturn

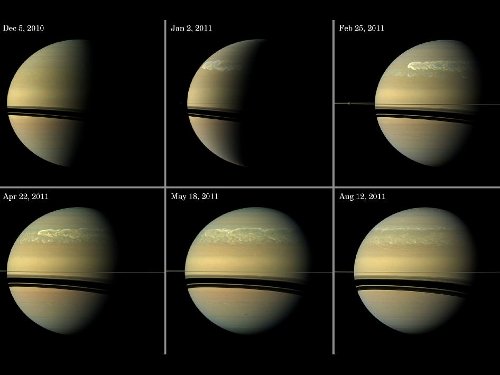

Storms on gas giants are awe-inspiring events, as witness what has been happening on Saturn since December of 2010. For a year now a monster storm extending 15000 kilometers north to south has been pummelling the northern latitudes. The Cassini images below takes us back to the earliest trace of the storm on December 5, 2010 and follow it through the middle of 2011, with views acquired at distances ranging from 2.2 million kilometers to 3 million kilometers.

Image: This series of images from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft shows the development of the largest storm seen on the planet since 1990. These true-color and composite near-true-color views chronicle the storm from its start in late 2010 through mid-2011, showing how the distinct head of the storm quickly grew large but eventually became engulfed by the storm’s tail. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

This is the longest lasting storm of this kind ever seen on Saturn, and it’s a far cry from the kind of weather we see on Earth:

“The Saturn storm is more like a volcano than a terrestrial weather system,” said Andrew Ingersoll, a Cassini imaging team member at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “The pressure builds up for many years before the storm erupts. The mystery is that there’s no rock to resist the pressure – to delay the eruption for so many years.”

What we’re learning about Saturn’s weather is that major storms come in outbursts separated by 20 to 30 years, which suggests a mechanism deep inside the planet that remains unknown. More in this CICLOPS news release.

These idea that this is a ‘volcano’ seems infeasible. As the quote suggests, the idea that a gaseous mass could restrain the eruption is difficult to comprehend. So, similar to my comment on the Europa ice volcanoes, I wonder whether this ‘storm’ could be the consequence of a meteor strike. Such an event would certainly roil the gas clouds. Do (any, if they exist) previous images of the area of the storm show impact(or)s?

I like this Big Dumb Object term, not in the sense that the object is dumb but that we are struck dumb when we find it.

I know far too little about these kinds of storms, but the fact that they apparently move exactly in perpedicular to the planet’s rotational axis (the same holds true for the “red spot” on Jupiter), I imagine this might not just be a coincidence. Large storms on Earth don’t just move along at always the same latitude.

On the other hand, maybe storms on Earth are just out of the norm due to its unique surface features (oceans vs land, especially mountains), which gas giants lack for obvious reasons. So let’s say Earth’s surface were completely flat, for example just a single huge ocean, would storms also move along the same latitude for their entire lifetime?

Beware of common sense assumptions about gas and air when contemplating the interiors of giant planets. Their atmospheres resemble ours only for the upper few hundred kilometers. Below that depth they transition to dense, supercritical fluids and below *that* you have things like metallic hydrogen. These realms are not well understood, but dismissing them as mere gas would be a mistake.