Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

How Many Brown Dwarfs in the Milky Way?

Interesting news keeps coming out of the National Astronomy Meeting in the UK. Today it involves brown dwarfs and their distribution throughout the galaxy, a lively question given how recently we’ve begun to study these ‘failed stars.’ Maybe we need a better name than ‘brown dwarfs,’ for that matter, since these objects are low enough in mass that they cannot sustain stable hydrogen fusion in their core. In a murky intermediary zone between planet and star, they can produce planets of their own but straddle all our contemporary definitions.

At the NAS meeting, an international team led by Koraljka Muzic (University of Lisbon) has reported on its work on brown dwarfs in clusters. It seems a sensible approach — go to the places where young stars are forming and try to figure out how many brown dwarfs emerge alongside them. That could help to give us an overview, because the brown dwarfs we’ve already found (beginning with the first, in 1995) are generally within 1500 light years of the Sun. Cluster studies should help us gain some sense of their broader distribution.

Clusters, after all, give birth to all kinds of stars from tens of solar masses down to the brown dwarfs we’re looking for, and the so-called initial mass function (IMF) showing the distribution of the different masses in young clusters has received plenty of attention. A key figure in its earlier study was Edwin Salpeter, an emigrant from Austria to Australia who wound up teaching at Cornell University. His work on the initial mass function led to values still accepted today down to stars of about half a solar mass, but things below that get murkier.

Image: False-colour near-infrared image of the core of the young massive cluster RCW 38 taken with the adaptive-optics camera NACO at the ESO’s Very Large Telescope. RCW 38 lies at a distance of about 5,500 light-years from the Sun. The field of view of the central image is approximately 1 arc minute, or 1.5 light-years across. Credit: Koraljka Muzic, University of Lisbon, Portugal / Aleks Scholz, University of St Andrews, UK / Rainer Schoedel, University of Granada, Spain / Vincent Geers, UKATC Edinburgh, UK / Ray Jayawardhana, York University, Canada / Joana Ascenso, University of Lisbon, University of Porto, Portugal, Lucas Cieza, University Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile. The study is based on observations conducted with the VLT at the European Southern Observatory.

Thus the need to update the IMF in the low mass range, a key part of what Muzic and team call Substellar Objects in Nearby Young Clusters, their survey to examine substellar populations in nearby star-forming regions. Recent studies have indicated that a single underlying initial mass function can explain the ratios of stars to brown dwarfs in the clusters studied. But most of the clusters studied to date have been loose groups of low mass stars.

Having already looked at five nearby star-forming regions, Muzic’s group chose to study brown dwarf formation in more massive, dense embedded clusters and homed in on the more distant cluster RCW 38, some 5500 light years out in the constellation Vela. This is a young cluster (less than a million years) that is twice as dense as the Orion Nebula Cluster and orders of magnitude denser than other nearby star forming regions. Packed with massive stars, it seems the ideal place to determine whether different starting conditions produce a different ratio of brown dwarfs to other types of star.

From the paper:

According to various BD formation theories, stellar density is expected to affect the production of very-low mass objects (high densities favor higher production rate of BDs), as well as the presence of massive OB stars capable of stripping the material around nearby pre-stellar cores until leaving an object not massive enough to form another star. In addition to the theoretical expectations, we discussed several observational hints for environmental differences in the nearby star forming regions from the literature, which, however, require further investigation. To that end, we choose to study a cluster that is several orders of magnitude denser than any of the nearby star forming regions (except for the ONC [Orion Nebula Cluster]), and also, unlike them, rich in massive stars.

Working with adaptive optics observations via the NAOS-CONICA imager at the European Space Agency’s Very Large Telescope, the researchers found values for brown dwarf formation that agreed with other young star-forming regions, even those much less dense. The results were clearcut, as the paper notes:

…leaving no evidence for environmental differences in the efficiency of the production of BDs and very-low mass stars possibly caused by high stellar densities or a presence of numerous massive stars.

And this:

In all regions studied so far, the star/BD ratio is between 2 and ? 5, i.e. for each 10 low-mass stars between 2 and 5 BDs are expected to be formed. This is also consistent with estimates of the star/BD ratio in the field (? 5; Bihain & Scholz 2016). The sum of these results clearly shows that brown dwarf formation is a universal process and accompanies star formation in diverse star forming environments across the Galaxy.

Interesting indeed! The brown dwarf population of the galaxy, based on this survey, is at least 25 billion and may range as high as 100 billion brown dwarfs, which would mean a brown dwarf for every hydrogen-burning star. The range results from the difficulty in observing such small, faint objects, raising the prospect that even the high number here may be an underestimate. Another cause for the variation: Star formation rates in the Milky Way seem to have been higher in the past. If this is the case, the 100 billion number seems more likely.

And note this: The calculations on the brown dwarf population were derived only for brown dwarfs more massive than 0.03 solar masses. Compare this to Jupiter’s mass, which is 0.00095 that of the Sun. Between the two is a wide range of possibilities.

“It seems that brown dwarfs form in abundance in a variety of star clusters,” says Ray Jayawardhana (York University), a member of the research team. “They are ubiquitous denizens of our Milky Way galaxy.”

The paper is Muzic, et al., “The Low-Mass Content of the Massive Young Star Cluster RCW 38,” submitted to Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (preprint).

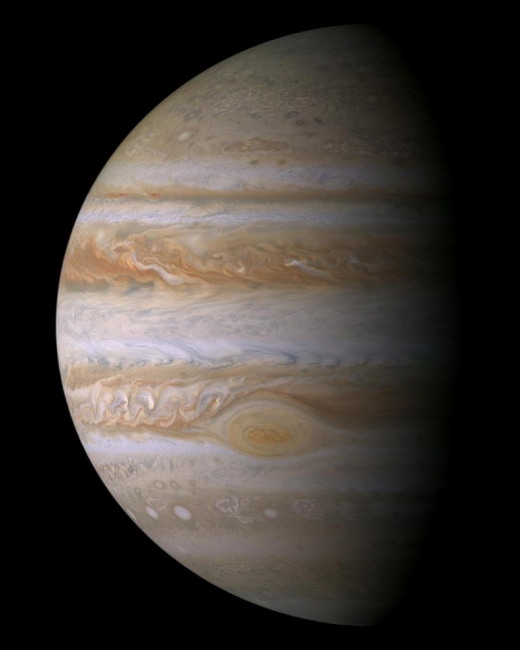

Juno’s Upcoming Run over the Great Red Spot

I love the image of Jupiter below because of the detail — a mosaic of 27 images taken on closest approach by Cassini in 2000, it shows visible features down to 60 kilometers across. Nine images covering the entire planet were acquired in red, green and blue to provide color much like what our eyes would see if we were there. The Great Red Spot, nestled among the clouds of ammonia, hydrogen sulfide and water, is obvious. But we’ll soon learn much more, for the Juno spacecraft is scheduled to fly directly over the Great Red Spot on July 10.

Image: This true color mosaic of Jupiter was constructed from images taken by the narrow angle camera onboard NASA’s Cassini spacecraft on December 29, 2000, during its closest approach to the giant planet at a distance of approximately 10 million kilometers. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

Launched on August 5, 2011, Juno completed its first year in Jupiter orbit on July 4, a reminder of how well shielded its instruments are in this tough environment. Rick Nybakken is project manager for Juno from JPL:

“The success of science collection at Jupiter is a testament to the dedication, creativity and technical abilities of the NASA-Juno team. Each new orbit brings us closer to the heart of Jupiter’s radiation belt, but so far the spacecraft has weathered the storm of electrons surrounding Jupiter better than we could have ever imagined.”

Indeed. Data collection from the Great Red Spot, a centuries-old, 16,000-kilometer wide storm, will be part of the spacecraft’s sixth science flyby, with perijove (the closest point in the orbit to Jupiter’s center) occurring on July 10 at 0955 EDT (1355 UTC). At this point, Juno will be about 3500 kilometers above the cloud tops. Less than 12 minutes later, the spacecraft will have moved directly above the huge storm, passing about 9000 kilometers above the Great Red Spot’s clouds, with all eight instruments as well as the JunoCam imager active.

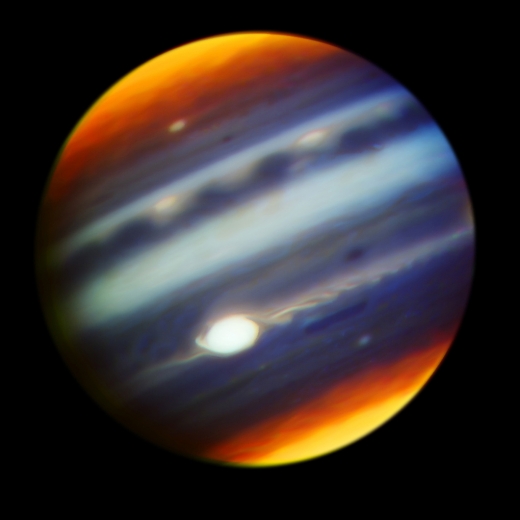

Earth-based telescopes have provided continuing observations of Jupiter in coordination with Juno, and on May 18, 2017, both the Gemini North and Subaru telescopes (both on Mauna Kea) simultaneously studied the planet in high resolution at different wavelengths, helping to provide data on atmospheric dynamics at various depths at the Great Red Spot and other regions of Jupiter. The image below was taken at infrared wavelengths, where the Great Red Spot appears brightest and high-altitude clouds and hazes become strikingly evident.

Image: This composite, false-color infrared image of Jupiter reveals haze particles over a range of altitudes, as seen in reflected sunlight. It was taken using the Gemini North Telescope’s Near-InfraRed Imager (NIRI) on May 18, 2017, in collaboration with the investigation of Jupiter by NASA’s Juno mission. Juno completed its sixth close approach to Jupiter a few hours after this observation. Credit: Gemini Observatory/AURA/NASA/JPL-Caltech.

You can see a prominent wave pattern north of the equator, with two bright ovals that are anticyclones that appeared in January of this year. Both are evidently an indication of an upsurge in storm activity that has been observed in these latitudes in 2017. Another bright anticyclonic oval can be seen further north. And note the hook-like shape on the left side of the Great Red Spot, an indication of intense winds stretching out atmospheric features. More traces of this wave-like flow pattern can be seen sweeping off its eastern (right) side.

“Observations with Earth’s most powerful telescopes enhance the spacecraft’s planned observations by providing three types of additional context,” said Juno science team member Glenn Orton of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. “We get spatial context from seeing the whole planet. We extend and fill in our temporal context from seeing features over a span of time. And we supplement with wavelengths not available from Juno. The combination of Earth-based and spacecraft observations is a powerful one-two punch in exploring Jupiter.”

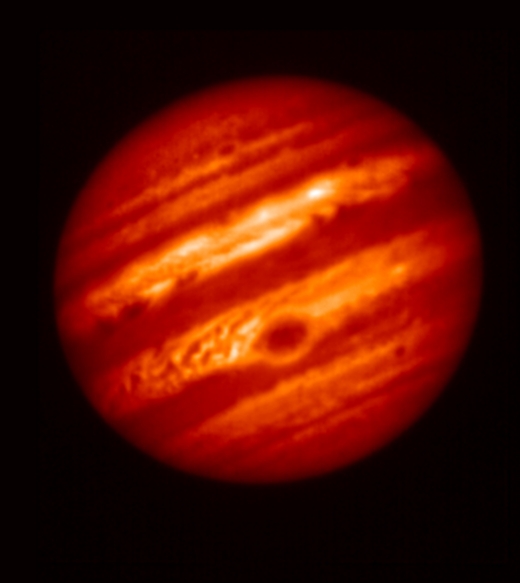

Image: This false-color image of Jupiter was taken on May 18, 2017, with a mid-infrared filter centered at a wavelength of 8.8 microns, at the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, in collaboration with observations of Jupiter by NASA’s Juno mission. The selected wavelength is sensitive to Jupiter’s tropospheric temperatures and the thickness of a cloud near the condensation level of ammonia gas. Credit: NAOJ/NASA/JPL-Caltech.

174P/Echeclus: Focus on an Unusual Centaur

Centaurs are intriguing objects, and not just because of the problem in figuring out what they are. For one thing, the farthest points in their orbits take them between the orbits of the outer planets in our Solar System. That makes them unstable, yielding lifetimes on the order of a few million years. They also show characteristics of both asteroids and comets, which makes objects like 174P/Echeclus so intriguing. Discovered in 2000, it was classified as a minor planet before a cometary coma appeared. Thus its current cometary designation.

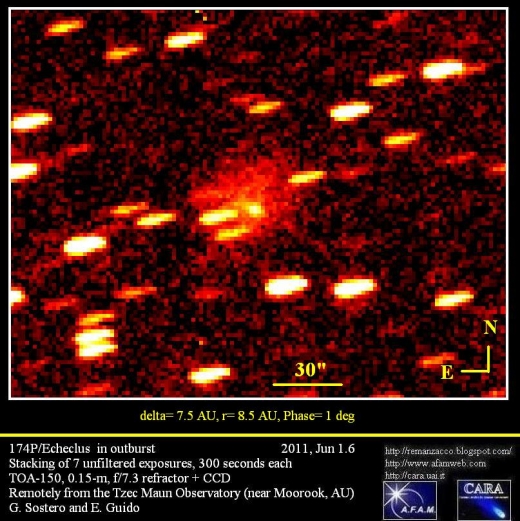

So what exactly do we have here? In 2005, a large piece of 174P/Echeclus broke off, possibly the result of an impact or, despite a distance at the time of over 13 AU from the Sun, perhaps the release of volatiles. We saw another outburst in 2011 at a distance of 8.5 AU from the Sun. Maria Womack (University of South Florida), who is lead author of a new paper on Echeclus, calls it “a bizarre solar system object,” which sounds about right, though other Centaurs — 2060 Chiron and 166P/NEAT — display comas reminiscent of those in comets.

Image: 174P/Echeclus in outburst mode in June of 2011. Credit: G. Sostero/E. Guido. Found at Guido’s excellent Comets & Asteroids site.

That Centaurs are odd objects is further confirmed by the largest confirmed member of their class, 10199 Chariklo, big enough at 260 km in diameter to be a mid-sized asteroid, and known to have a system of rings. We don’t see any comet-like activity here, but two other Centaurs — 52872 Okyrhoe and 2012 CG — have produced what may have been coma activity in the past. Will any Centaur that moves into the inner system become a comet?

For that matter, why do objects like these produce large, observable emissions while still far from the Sun? The average comet, often rich in frozen volatiles like carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, hydrogen cyanide and methanol, loses ice through sublimation and produces jets of water vapor and other gases only as it approaches the inner system. Perhaps one reason for the difference, the researchers learned, has to do with the composition of Centaurs.

What Womack and team found at Echeclus is that the object shows levels of carbon monoxide nearly 40 times lower than we would expect from comets at similar distances from the Sun. The implication is that this makes Echeclus, and by implication other Centaurs, more fragile than the average comet. The reason for the deficiency of carbon monoxide is unknown, though it may relate to physical processes that caused the CO to be lost.

The researchers used the Arizona Radio Observatory 10-m Submillimeter Telescope to search for CO at Echeclus in mid-2016, when the Centaur was 6.1 AU from the Sun. They found a production rate of carbon monoxide — Q(CO) — which turned out to be the lowest found in any Centaur, and 5 times lower than the carbon monoxide production found near aphelion. The same CO deficiency shows up in other Centaurs. The quoted segment from the paper below refers to Comet Hale-Bopp and the Centaur 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 (29P) for comparison:

Our data are consistent with Echeclus being a CO-deficient body, when comet Hale-Bopp’s data at ? 6 au is used as a proxy for a relatively unprocessed nucleus. When scaled by surface area and compared with CO measurements from other Centaurs, we see that specific production rates, Q(CO)/D2, from Echeclus and Chiron are ? 10-50 times below that of Hale-Bopp, and 29P, which are both known to be CO-rich.

But Centaurs will not yield their secrets easily. As the paper continues, we learn that CO deficiency is not a completely shared characteristic:

The lower CO output of Echeclus and Chiron may mean that they incorporated less CO into their nuclei than many other comets, or they may have lost a significant amount due to devolatilization while in their relatively close-to-the-Sun Centaur orbits. It is puzzling why 29P, another Centaur, is evidently CO-rich. Although no other CO detections exist for other Centaurs, stringent upper limits to their specific production rates show that several other Centaurs are also notably absent of CO outgassing, including Chariklo, 8405 Asbolus, 34842 and 95626.

Then bear in mind that we have evidence for fragments, rings and ring arcs around not just 10199 Chariklo but 29P, 2060 Chiron and Echeclus itself. Thus, as the paper points out, we need to make more measurements of CO production rates and fragmentation activity in other Centaurs to refine our models of their structure. The outer Solar System once again reminds us that our categories for these distant objects are subject to continuing revision.

“These are minor bodies that we are studying, but they can provide major insights,” says Gal Sarid (University of Central Florida), a co-author of the paper. “We believe they are rich in organics and could provide important hints of how life originated.”

The paper is Wierzchos, Womack & Sarid, “Carbon Monoxide in the Distantly Active Centaur (60558) 174P/Echeclus at 6 au,” Astronomical Journal Vol. 153, No. 5 (2017). Abstract.

M-Dwarf Habitability: New Work on Flares

The prospects for life around M-dwarf stars, always waxing and waning depending on current research, have dimmed again with the release of new work from Christina Kay (NASA GSFC) and colleagues. As presented at the National Astronomy Meeting at the University of Hull (UK), the study takes on the question of space weather and its effect on habitability.

We know that strong solar flares can disrupt satellites and ground equipment right here on Earth. But habitable planets around M-dwarfs — with liquid water on the surface — must orbit far closer to their star than we do. Proxima Centauri b, for example, is roughly 0.05 AU from its small red host (7,500,000 km), while all seven of the TRAPPIST-1 planets orbit much closer than Mercury orbits the Sun. What, then, could significant flare activity do to such vulnerable worlds?

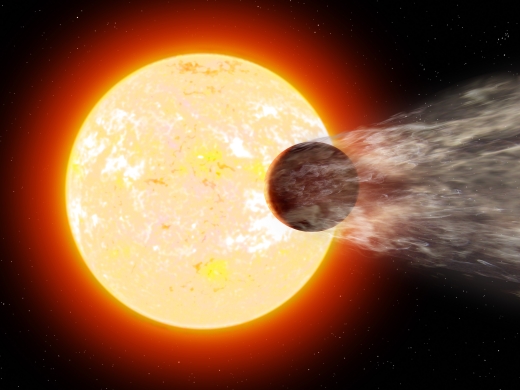

Image: Artist’s impression of HD 189733b, showing the planet’s atmosphere being stripped by the radiation from its parent star. Credit: Ron Miller.

Working with Merav Opher and Marc Kornbleuth (both at Boston University), Kay has homed in on coronal mass ejections (CMEs), the vast upheavals that throw stellar plasma into nearby space. While red dwarf stars are significantly cooler than our G-class Sun, their CMEs are thought to be far stronger because of their enhanced magnetic fields. From the paper:

Stellar activity tends to increase with the size of the stellar convection envelope (West et al. 2004) and stellar rotation rates (Mohanty et al. 2002; West et al. 2015), although the activity saturates for sufficiently high rotational velocity (Delfosse et al. 1998). For mid- to late-type M dwarfs (M4 to M8.5) the activity saturates at higher rotational velocities than for early-type M dwarfs, and above M9 the activity levels decrease significantly (Mohanty et al. 2002). Accordingly, most M dwarf stars will have significantly enhanced stellar activity as compared to the Sun.

A strong planetary magnetic field could counteract at least some of the resulting flare activity, but even there a possibility of strong erosion of the atmosphere remains. And if the planet is tidally locked, some recent work suggests little to no magnetic field can be expected.

The paper outlines the process when a CME hits a nearby planet. One problem is extreme ultraviolet and X-ray flux (XUV) which can heat the upper atmosphere and perhaps ionize it. If such radiation gets through to the surface, it can damage any potential life-forms there. While it turns out that an M-dwarf habitable zone planet receives an order of magnitude less XUV flux than Earth when the star is quiet, the flux jumps as high as 100 times Earth’s during the star’s frequent flare activity.

Significant CME activity also makes the planet much less likely to retain its atmosphere as a shield for life on the surface. A CME compresses whatever magnetosphere the planet has, and in extreme cases, say the authors, can exert enough pressure to shrink the magnetosphere to the point where the atmosphere can be seriously eroded.

Modeling an Astrospheric Current Sheet

Kay’s team modeled the effects of theoretical CMEs on the red dwarf V374 Pegasi, using a tool Kay developed for CME modeling called ForeCAT. They found that the strong magnetic fields of the star produce CMEs that can reach the so-called Astrospheric Current Sheet, where the background magnetic field is at its minimum. The same effect occurs with our Sun, when solar CMEs are deflected by magnetic forces toward the minimum magnetic energy.

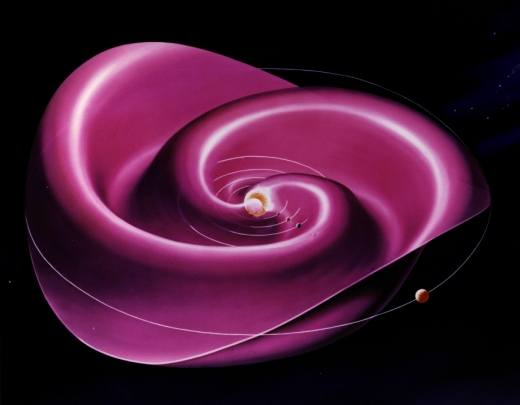

At the Sun, the Heliospheric Current Sheet — the local analog to a different star’s Astrospheric Current Sheet — is a field that extends along the Sun’s equatorial plane in the heliosphere and is shaped by the effect of the Sun’s rotating magnetic field on the plasma in the solar wind. The HCS separates regions of the solar wind where the magnetic field points toward or away from the Sun.

Let’s dwell on that for a moment. Here’s what a NASA fact sheet has to say about the Heliospheric Current Sheet:

The sun’s magnetic field permeates the entire solar system called the heliosphere. All nine planets orbit inside it. But the biggest thing in the heliosphere is not a planet, or even the sun. It’s the current sheet — a sprawling surface where the polarity of the sun’s magnetic field changes from plus (north) to minus (south). A small electrical current flows within the sheet, about 10?10 A/m². The thickness of the current sheet is about 10,000 km near the orbit of the Earth. Due to the tilt of the magnetic axis in relation to the axis of rotation of the sun, the heliospheric current sheet flaps like a flag in the wind. The flapping current sheet separates regions of oppositely pointing magnetic field, called sectors.

Image: The Heliospheric Current Sheet results from the influence of the Sun’s rotating magnetic field on the plasma in the interplanetary medium (solar wind). The wavy spiral shape has been likened to a ballerina’s skirt. The new work uses a software modeling package called ForeCAT to study interactions between CMEs and the Astrospheric Current Sheet around the red dwarf V374 Pegasi. Credit: NASA GSFC.

Kay and team have modeled the Astrospheric Current Sheet expected to be found around M-dwarfs like V374 Pegasi. The authors find that upon reaching the ACS, CMEs become ‘trapped’ along it. Planets can dip into and out of the ACS as they orbit. A CME moving out into the Astrospheric Current Sheet around an M-dwarf can cancel out a habitable zone planet’s local magnetic field, opening the world to devastating flare effects. The upshot:

We expect that rocky exoplanets cannot generate sufficient magnetic field to shield their atmosphere from mid-type M dwarf CMEs… We expect that the minimum magnetic field strength will change with M dwarf spectral type as the amount of stellar activity and stellar magnetic field strength change, and that early-type M dwarfs would be more likely to retain an atmosphere than mid or late-type M dwarfs.

The authors calculate that a mid-type M-dwarf planet would need a minimum planetary magnetic field between tens to hundreds of Gauss to retain an atmosphere, values that are far higher than Earth’s (0.25 to 0.65 gauss). CME impacts as numerous as five per day could occur for planets near the star’s Astrospheric Current Sheet. The only mitigating factor is that the rate decreases for planets in inclined orbits. The paper notes:

The sensitivity to the inclination is much greater for the mid-type M dwarf exoplanets due to the extreme deflections to the Astrospheric Current Sheet. For low inclinations we find a probability of 10% whereas the probability decreases to 1% for high inclinations. From our estimation of 50 CMEs per day, we expect habitable mid-type M dwarf exoplanets to be impacted 0.5 to 5 times per day, 2 to 20 times the average at Earth during solar maximum. The frequency of CME impacts may have significant implications for exoplanet habitability if the impacts compress the planetary magnetosphere leading to atmospheric erosion.

So we have much to learn about M-dwarfs. In particular, how accurate is the ForeCAT model in developing the CME scenario around such stars? As we examine such modeling, we have to keep in mind that magnetic field strength will change with the type of M-dwarf we are dealing with. Based on this research, only early M-dwarfs are likely to maintain an atmosphere.

The paper is Kay, Opher and Kornbleuth, “Probability of CME Impact on Exoplanets Orbiting M Dwarfs and Solar-Like Stars,” accepted at the Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

‘Cosmic Modesty’ in a Fecund Universe

I came across the work of Chin-Fei Lee (Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Taiwan) when I had just read Avi Loeb’s essay Cosmic Modesty. Loeb (Harvard University) is a well known astronomer, director of the Institute for Theory and Computation at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and a key player in Breakthrough Starshot. His ‘cosmic modesty’ implies we should accept the idea that humans are not intrinsically special. Indeed, given that the only planet we know that hosts life has both intelligent and primitive lifeforms on it, we should search widely, and not just around stars like our Sun.

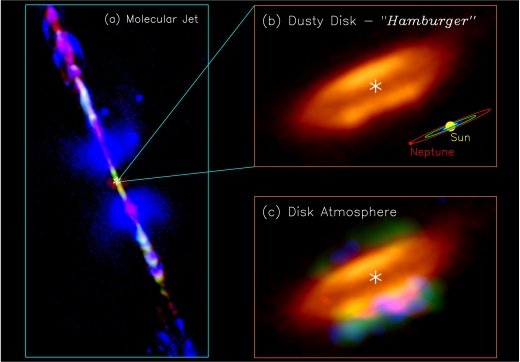

More on that in a moment, because I want to intertwine Loeb’s thoughts with recent work by Chin-Fei Lee, whose team has used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to detect organic molecules in an accretion disk around a young protostar. The star in question is Herbig-Haro (HH) 212, an infant system (about 40,000 years old) in Orion about 1300 light years away. Seen nearly edge-on from our perspective on Earth, the star’s accretion disk is feeding a bipolar jet. This team’s results, to my mind, remind us why cosmic modesty seems like a viable course, while highlighting the magnitude of the question.

Image: Harvard’s Avi Loeb. Credit: Harvard University.

What Lee’s team has found at HH 212 is an atmosphere of complex organic molecules associated with the disk. Methanol (CH3OH) is involved, as is deuterated methanol (CH2DOH), methanethiol (CH3SH), and formamide (NH2CHO), which the researchers see as precursors for producing biomolecules like amino acids and sugars. “They are likely formed on icy grains in the disk and then released into the gas phase because of heating from stellar radiation or some other means, such as shocks,” says co-author Zhi-Yun Li of the University of Virginia.

Every time I read about finds like this, I think about the apparent ubiquity of life’s materials — here we’re seeing organics at the earliest phases of a stellar system’s evolution. The inescapable conclusion is that the building blocks of living things are available from the outset to be incorporated in the planets that emerge from the disk. That certainly doesn’t count as a detection of life, but it does remind us of how frequently the ingredients of life manage to appear.

Image: Jet, disk, and disk atmosphere in the HH 212 protostellar system. (a) A composite image for the HH 212 jet in different molecules, combining the images from the Very Large Telescope (McCaughrean et al. 2002) and ALMA (Lee et al. 2015). Orange image shows the dusty envelope+disk mapped with ALMA. (b) A zoom-in to the central dusty disk. The asterisk marks the position of the protostar. A size scale of our solar system is shown in the lower right corner for comparison. (c) Atmosphere of the accretion disk detected with ALMA. In the disk atmosphere, green is for deuterated methanol, blue for methanethiol, and red for formamide. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/Lee et al.

In that context, Avi Loeb’s thoughts on cosmic modesty ring true. We’ve been able to extract some statistical conclusions from the Kepler instrument’s deep stare that let us infer there are more Earth-mass planets in the habitable zones of their stars in the observable universe than there are grains of sand on all the Earth’s beaches. Something to think about as you read this on your beach vacation and gaze from the sand beneath your feet to the ocean beyond.

But are most living planets likely to occur around G-class stars like our Sun? Loeb reminds us that red dwarf stars like Proxima Centauri b and TRAPPIST-1, both of which made headlines in the past year because of their conceivably habitable planets, are long-lived, with lifetimes as long as 10 trillion years. Our Sun’s life, by comparison, is a paltry 10 billion years. Long after the Sun has turned into a white dwarf after its red giant phase, living things could still have a habitat around Proxima Centauri and TRAPPIST-1. Says Loeb:

I therefore advise my wealthy friends to buy real estate on Proxima b, because its value will likely go up dramatically in the future. But this also raises an important scientific question: “Is life most likely to emerge at the present cosmic time near a star like the sun?” By surveying the habitability of the universe throughout cosmic history from the birth of the first stars 30 million years after the big bang to the death of the last stars in 10 trillion years, one reaches the conclusion that unless habitability around low-mass stars is suppressed, life is most likely to exist near red dwarf stars like Proxima Centauri or TRAPPIST-1 trillions of years from now.

But of course, one of the reasons for missions like TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) is to begin to understand the small rocky worlds around nearby red dwarfs, and to determine whether there are factors like tidal lock or stellar flaring that preclude life there. For that matter, do the planets around Proxima and TRAPPIST-1 have atmospheres? There too the answer will be forthcoming, assuming the James Webb Space Telescope is deployed successfully and can make the needed assessment of these worlds.

…very advanced civilizations [Loeb continues] could potentially be detectable out to the edge of the observable universe through their most powerful beacons. The evidence for an alien civilization might not be in the traditional form of radio communication signals. Rather, it could involve detecting artifacts on planets via the spectral edge from solar cells, industrial pollution of atmospheres, artificial lights or bursts of radiation from artificial beams sweeping across the sky.

Changes to the traditional view of SETI abound as we explore these new pathways. In any case, our technologies for making such detections have never been as advanced, and work across the exoplanetary spectrum, such as the findings of Chin-Fei Lee and colleagues, urges us on as we try to relate our own civilization to a universe in which it is hardly the center. As Loeb reminds us, we are orbiting a galaxy that itself moves at ~0.001c relative to the cosmic rest frame, one of perhaps 100 billion galaxies in the observable universe.

Either alternative — we are alone, or we are not — changes everything about our perspective, and encourages us to deepen the search for simple life (perhaps detected in exoplanetary atmospheres through its biosignatures) as well as conceivable alien civilizations. Embracing Loeb’s cosmic modesty, we press on under the assumption that life’s emergence is not uncommon, and that refining the search to learn the answer is a civilizational imperative.

Magnetic Reconnection at the ‘Planet of Doubt’

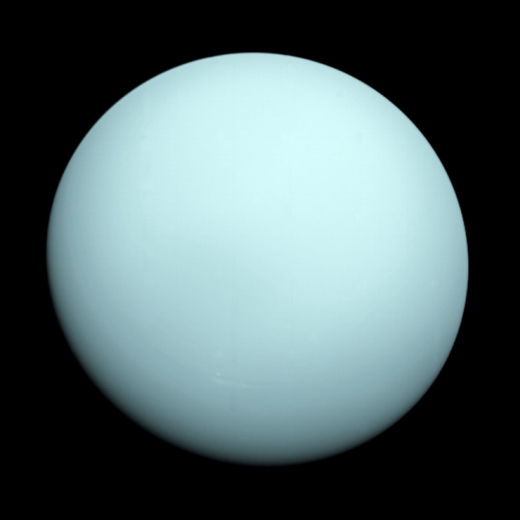

Perhaps the image of Uranus just below helps explain why the planet has been treated so sparsely in science fiction. Even this Voyager view shows us a featureless orb, and certainly in visible light the world has little to make it stand out other than its unusual axis of rotation, which is tilted so that its polar regions are where you would expect its equator to be. Geoff Landis’ “Into the Blue Abyss” (2001) is the best fictional treatment I know, but the fog-shrouded Uranus of Stanley G. Weinbaum’s “The Planet of Doubt” (1935) has its own charms, though obviously lacking the scientific verisimilitude of the Landis tale.

My admiration for Gerald Nordley’s “Into the Miranda Rift” (1993) is unabated, taking us into this strange world’s most dramatic moon, while I should also mention Kim Stanley Robinson’s visit to Uranus in Blue Mars (1997), where the moon is established as a protected wilderness site while the rest of the Uranian satellite system is under colonization. Fritz Leiber’s “Snowbank Orbit” (1962) explores aero-braking at Uranus, while Larry Niven’s A World Out of Time (1976) maneuvers the planet to adjust the Earth’s own orbit.

Image: The planet Uranus as seen by Voyager 2, which flew closely past the seventh planet in January of 1986. Credit: NASA/JPL.

I will spare you the 1962 film Journey to the Seventh Planet and move on to new work on Uranus out of the Georgia Institute of Technology, where researchers have discovered that the magnetosphere of the planet ‘flips on and off like a light switch’ (according to this Georgia Tech news release) as it rotates along with the planet. In one orientation, the solar wind flows into the magnetosphere, which later closes to deflect that same wind away from Uranus.

Rotating on its side, Uranus also has a magnetic field that is off-centered and tilted 60 degrees from its axis of rotation. What we wind up with is rapid rotational reorientation, keeping the field strength turbulent. Carol Paty (Georgia Tech), a co-author of the study, puts the matter this way:

“Uranus is a geometric nightmare. The magnetic field tumbles very fast, like a child cartwheeling down a hill head over heels. When the magnetized solar wind meets this tumbling field in the right way, it can reconnect and Uranus’ magnetosphere goes from open to closed to open on a daily basis.”

Compare this with the Earth, where the magnetic field is nearly aligned with the planet’s spin axis, which means that the magnetosphere spins along with the Earth’s rotation. Even so, disruptive events can occur because of geomagnetic storms. A strong solar storm disrupting the magnetic fields of the solar wind can reconfigure Earth’s field from closed to open, rearranging the local magnetic topology to allow a surge of solar energy to enter the system. Such reconnection happens throughout the Solar System, and occurs when the direction of the heliospheric magnetic field is opposite to a planet’s magnetospheric alignment.

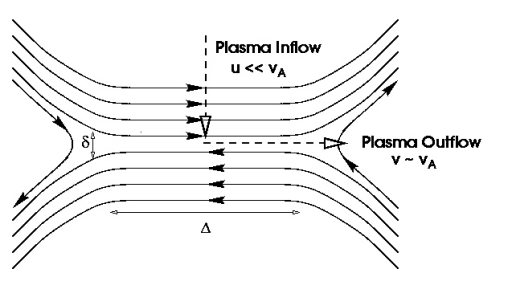

Geomagnetic storms produced by coronal mass ejections slamming into Earth’s magnetic field can produce spectacular aurora events while playing havoc with radio communications. Reconnection drives the entire process, happening in the presence of plasma, which carries its own magnetic fields in a constantly adjusting dance between charged particles and fields. Sudden changes in the alignment of the magnetic field lines convert the stored energy of the magnetic fields into heat and kinetic energy that drives particles along the field lines.

Image: Magnetic reconnection (henceforth called “reconnection”) refers to the breaking and reconnecting of oppositely directed magnetic field lines in a plasma. In the process, magnetic field energy is converted to plasma kinetic and thermal energy. Credit: Magnetic Reconnection Experiment.

Thus a surge of energy enters the system. Such magnetic reconnection should produce auroras at various latitudes on Uranus even if they are a challenge to observe from Earth. The Georgia Tech team’s numerical models predict the most likely places on the planet for reconnection, working with Voyager 2 data from the 1986 flyby. Lead author Xin Cao comments:

“The majority of exoplanets that have been discovered appear to also be ice giants in size. Perhaps what we see on Uranus and Neptune is the norm for planets: very unique magnetospheres and less-aligned magnetic fields. Understanding how these complex magnetospheres shield exoplanets from stellar radiation is of key importance for studying the habitability of these newly discovered worlds.”

The paper is Cao and Paty, “Diurnal and seasonal variability of Uranus’s magnetosphere,” published online by the Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 27 June 2017 (abstract).