Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Terrain Clues to Ice in the Outer System

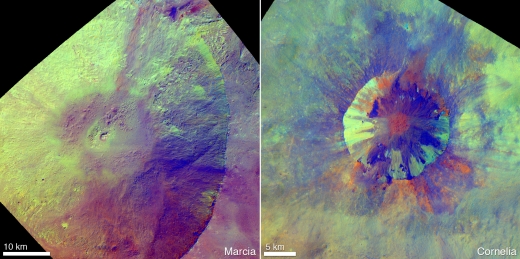

The human expansion into the Solar System will demand our being able to identify sources of water, a skill we’re honing as explorations continue. On Mars, for example, the study of so-called ‘pitted craters’ has been used as evidence that the low latitude regions of the planet, considered its driest, nonetheless have a layer of underlying ice. The Dawn spacecraft discovered similar pitted terrain on Vesta, as you can see in the image below.

Image: These enhanced-color views from NASA’s Dawn mission show an unusual “pitted terrain” on the floors of the craters named Marcia (left) and Cornelia (right) on the giant asteroid Vesta. The views show that the physical properties or composition of the material in which these pits form is different from crater to crater. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA/JHUAPL.

Vesta’s Marcia crater contains the largest number of pits on the asteroid. The 70-kilometer feature is also one of the youngest craters found there. So what accounts for this kind of terrain? Perhaps the water that formed the pits came from Vesta itself. Another possibility: Low-speed collisions with carbon-rich meteorites could have deposited hydrated materials on the surface, to be released in the heat of subsequent high-speed collisions within the asteroid belt. An explosive degassing into space could explain such pothole-like depressions.

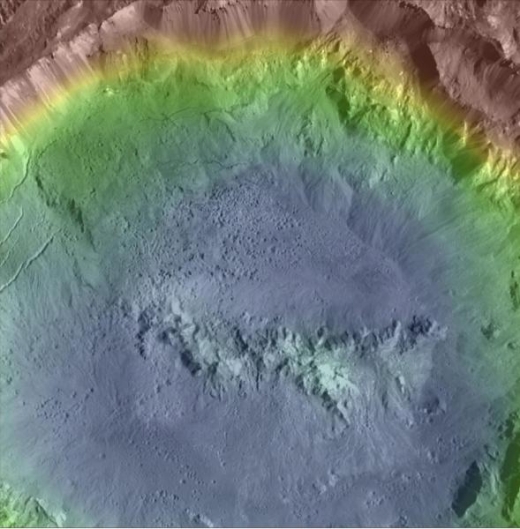

But Dawn wasn’t through when it left Vesta, and what it has found at Ceres is proving invaluable at understanding what appears to be a common marker of volatile-rich material. In new work from Hanna Sizemore (Planetary Science Institute) and colleagues, we learn that Ceres is home to the same kind of pitted terrain. As Sizemore notes:

“Now, we’ve found this same type of morphological feature on Ceres, and the evidence suggests that ice in the Cerean subsurface dominated the formation of pits there. Finding this type of feature on three different bodies suggests that similar pits might be found on other asteroids we will explore in the future, and that pitted materials may mark the best places to look for ice on those asteroids.”

Image: Haulani Crater, Ceres, showing abundant pitted materials on the crater floor. Similar pitted materials have previously been identified on Mars and Vesta, and are associated with rapid volatile release following impact. Their discovery on Ceres indicates pitted materials may be a common morphological indicator of volatile-rich materials in the asteroid belt. Haulani Crater is 34 km in diameter. Color indicates topography. Credit: NASA/MPS/PSI/Thomas Platz.

Sizemore’s team studied the formation of pitted craters on Ceres through numerical models that explored the role of water ice and other volatiles. The morphological similarities between the Ceres features and what has been found on Mars and Vesta are striking. With water ice evidently significant in pit development on two asteroids and a planet, similar terrains will be of clear interest for future missions in terms of in situ resource utilization.

Image: Pitted terrain on Mars as seen by HiRISE aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona.

The paper is Sizemore et al., “Pitted Terrains on (1) Ceres and Implications for Shallow Subsurface Volatile Distribution,” accepted at Geophysical Research Letters (preprint).

Toward a Planet Formation Model for Pulsars

Our theories of planet formation grow more mature as the exoplanet census continues, but I’ve always speculated about the first planets discovered and how they could have possibly been where we found them. The discovery of the planets around the pulsar PSR B1257+12 occurred in 1992, the work of the Polish astronomer Aleksander Wolszczan. Anomalies in its pulsation period — this is a millisecond pulsar with a period of 6.22 milliseconds — led Wolszczan and Dale Frail to produce a paper on the first extrasolar planets ever found.

We wouldn’t find such planets at all if it were not for the effect of their gravitational pull on the otherwise regular pulses from the pulsar. But how could the planets now know as Draugr, Poltergeist and Phobetor, the latter found in 1994, possibly have formed in such an environment? After all, a dense neutron star (a pulsar is a highly magnetized, rotating neutron star) is the result of a supernova that should have destroyed any planets nearby, making it necessary for planet formation to occur from raw materials around the resulting object.

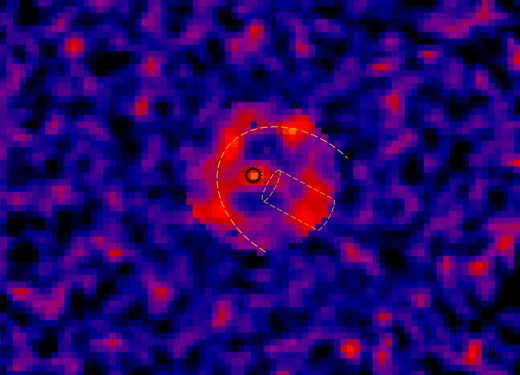

Jane Greaves (University of Cardiff), working with Wayne Holland (UK Astronomy Technology Centre, Edinburgh) presented results at the recent National Astronomy Meeting that the duo have assembled into a new paper. The researchers focused on the Geminga pulsar, about 800 light years from the Sun in the constellation Gemini. A quick check of Wikipedia produced this delightful bit about the name Geminga: It’s a contraction of ‘Gemini gamma-ray source’ as well as a transcription of words meaning ‘it’s not there’ in the Lombard dialect of northern Italy.

Geminga really is there, and at one point the explosion that created it was considered the reason for the low density of the interstellar medium through which the Sun now passes, a theory that is now out of favor. Greaves and Holland observed Geminga at submillimeter wavelengths with the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in Hawaii. The pulsar is surrounded by a pulsar wind nebula (PWN), a type of nebula found inside the shells of supernova remnants that is powered by pulsar ‘winds’ driven by the central pulsar.

Indeed, earlier data from the WISE mission had suggested a ‘shell-like parabolic structure comprising a number of clumps’ around Geminga, and the authors’ new work amplifies on that discovery. Multiple observing runs with different cameras showed Greaves and Holland faint material near the pulsar and an arc around it. Says Greaves:

“This seems to be like a bow-wave – Geminga is moving incredibly fast through our Galaxy, much faster than the speed of sound in interstellar gas. We think material gets caught up in the bow-wave, and then some solid particles drift in towards the pulsar.”

Image: Data at wavelength of 0.45 mm, combined from SCUBA and SCUBA-2 [the cameras used in this work] in a false-colour image. The Geminga pulsar (inside the black circle) is moving towards the upper left, and the orange dashed arc and cylinder show the ‘bow-wave’ and a ‘wake’. The region shown is 1.3 light-years across; the bow-wave probably stretches further behind Geminga, but SCUBA imaged only the 0.4 light-years in the centre. Credit: Jane Greaves / JCMT / EAO.

The hypothesis, then, is that dust from the interstellar medium interacting with the pulsar wind nebula around Geminga accumulates the raw materials for future planets, rather than interactions between the pulsar wind nebula and the pulsar itself. The pulsar’s movement through the interstellar medium is the key, at least for this pulsar. From the paper:

The origins of the rare pulsar planet systems are uncertain, with recent work (Margalit & Metzger 2017) favouring disruption of a companion over re-accretion of supernova fallback material. Here we find evidence that the middle-aged Geminga pulsar is surrounded by a shell of material which could have formed from compression of the local ISM. Preliminary calculations suggest that dust could penetrate the nebula, given the low space speed and local density, and this may provide an alternate source for dust near this pulsar. A candidate circum-pulsar disc would be the first to be found in the submillimetre, complementing the only infrared candidate (around the magnetar 4U 0142+61, Wang et al. 2006).

And the researchers seem to have found enough mass to do the job:

We are waiting for higher-resolution follow-up data, but can infer that any dust disc present around Geminga should exceed about 6 Earth-masses of dust. Thus it would have potential to form low-mass planets, such as the archetypes around PSR B1257+12 (Wolszczan & Frail 1992).

The authors have applied for time on the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), hoping to tease out more detail, enough to demonstrate that the faint debris they have spotted so far around Geminga really is associated with the object. A confirmation there would lead to work on other pulsar systems to probe deeper into planet formation in unusual environments.

The paper is Greaves & Holland, “The Geminga pulsar wind nebula in the mid-infrared and submillimetre,” published online by Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 15 June 2017 (abstract).

How Many Brown Dwarfs in the Milky Way?

Interesting news keeps coming out of the National Astronomy Meeting in the UK. Today it involves brown dwarfs and their distribution throughout the galaxy, a lively question given how recently we’ve begun to study these ‘failed stars.’ Maybe we need a better name than ‘brown dwarfs,’ for that matter, since these objects are low enough in mass that they cannot sustain stable hydrogen fusion in their core. In a murky intermediary zone between planet and star, they can produce planets of their own but straddle all our contemporary definitions.

At the NAS meeting, an international team led by Koraljka Muzic (University of Lisbon) has reported on its work on brown dwarfs in clusters. It seems a sensible approach — go to the places where young stars are forming and try to figure out how many brown dwarfs emerge alongside them. That could help to give us an overview, because the brown dwarfs we’ve already found (beginning with the first, in 1995) are generally within 1500 light years of the Sun. Cluster studies should help us gain some sense of their broader distribution.

Clusters, after all, give birth to all kinds of stars from tens of solar masses down to the brown dwarfs we’re looking for, and the so-called initial mass function (IMF) showing the distribution of the different masses in young clusters has received plenty of attention. A key figure in its earlier study was Edwin Salpeter, an emigrant from Austria to Australia who wound up teaching at Cornell University. His work on the initial mass function led to values still accepted today down to stars of about half a solar mass, but things below that get murkier.

Image: False-colour near-infrared image of the core of the young massive cluster RCW 38 taken with the adaptive-optics camera NACO at the ESO’s Very Large Telescope. RCW 38 lies at a distance of about 5,500 light-years from the Sun. The field of view of the central image is approximately 1 arc minute, or 1.5 light-years across. Credit: Koraljka Muzic, University of Lisbon, Portugal / Aleks Scholz, University of St Andrews, UK / Rainer Schoedel, University of Granada, Spain / Vincent Geers, UKATC Edinburgh, UK / Ray Jayawardhana, York University, Canada / Joana Ascenso, University of Lisbon, University of Porto, Portugal, Lucas Cieza, University Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile. The study is based on observations conducted with the VLT at the European Southern Observatory.

Thus the need to update the IMF in the low mass range, a key part of what Muzic and team call Substellar Objects in Nearby Young Clusters, their survey to examine substellar populations in nearby star-forming regions. Recent studies have indicated that a single underlying initial mass function can explain the ratios of stars to brown dwarfs in the clusters studied. But most of the clusters studied to date have been loose groups of low mass stars.

Having already looked at five nearby star-forming regions, Muzic’s group chose to study brown dwarf formation in more massive, dense embedded clusters and homed in on the more distant cluster RCW 38, some 5500 light years out in the constellation Vela. This is a young cluster (less than a million years) that is twice as dense as the Orion Nebula Cluster and orders of magnitude denser than other nearby star forming regions. Packed with massive stars, it seems the ideal place to determine whether different starting conditions produce a different ratio of brown dwarfs to other types of star.

From the paper:

According to various BD formation theories, stellar density is expected to affect the production of very-low mass objects (high densities favor higher production rate of BDs), as well as the presence of massive OB stars capable of stripping the material around nearby pre-stellar cores until leaving an object not massive enough to form another star. In addition to the theoretical expectations, we discussed several observational hints for environmental differences in the nearby star forming regions from the literature, which, however, require further investigation. To that end, we choose to study a cluster that is several orders of magnitude denser than any of the nearby star forming regions (except for the ONC [Orion Nebula Cluster]), and also, unlike them, rich in massive stars.

Working with adaptive optics observations via the NAOS-CONICA imager at the European Space Agency’s Very Large Telescope, the researchers found values for brown dwarf formation that agreed with other young star-forming regions, even those much less dense. The results were clearcut, as the paper notes:

…leaving no evidence for environmental differences in the efficiency of the production of BDs and very-low mass stars possibly caused by high stellar densities or a presence of numerous massive stars.

And this:

In all regions studied so far, the star/BD ratio is between 2 and ? 5, i.e. for each 10 low-mass stars between 2 and 5 BDs are expected to be formed. This is also consistent with estimates of the star/BD ratio in the field (? 5; Bihain & Scholz 2016). The sum of these results clearly shows that brown dwarf formation is a universal process and accompanies star formation in diverse star forming environments across the Galaxy.

Interesting indeed! The brown dwarf population of the galaxy, based on this survey, is at least 25 billion and may range as high as 100 billion brown dwarfs, which would mean a brown dwarf for every hydrogen-burning star. The range results from the difficulty in observing such small, faint objects, raising the prospect that even the high number here may be an underestimate. Another cause for the variation: Star formation rates in the Milky Way seem to have been higher in the past. If this is the case, the 100 billion number seems more likely.

And note this: The calculations on the brown dwarf population were derived only for brown dwarfs more massive than 0.03 solar masses. Compare this to Jupiter’s mass, which is 0.00095 that of the Sun. Between the two is a wide range of possibilities.

“It seems that brown dwarfs form in abundance in a variety of star clusters,” says Ray Jayawardhana (York University), a member of the research team. “They are ubiquitous denizens of our Milky Way galaxy.”

The paper is Muzic, et al., “The Low-Mass Content of the Massive Young Star Cluster RCW 38,” submitted to Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (preprint).

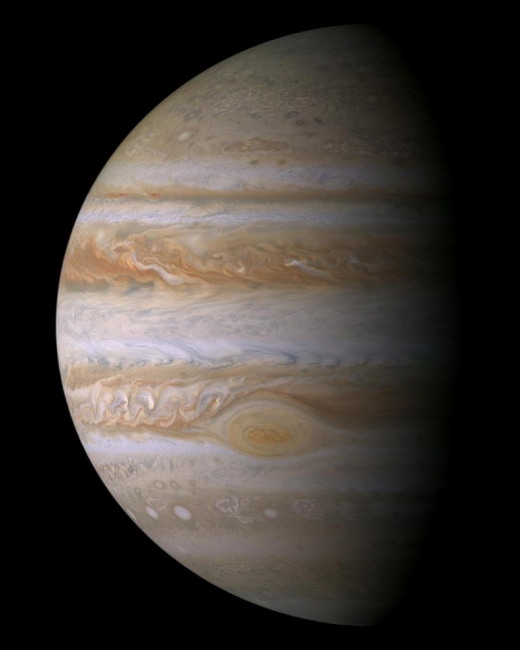

Juno’s Upcoming Run over the Great Red Spot

I love the image of Jupiter below because of the detail — a mosaic of 27 images taken on closest approach by Cassini in 2000, it shows visible features down to 60 kilometers across. Nine images covering the entire planet were acquired in red, green and blue to provide color much like what our eyes would see if we were there. The Great Red Spot, nestled among the clouds of ammonia, hydrogen sulfide and water, is obvious. But we’ll soon learn much more, for the Juno spacecraft is scheduled to fly directly over the Great Red Spot on July 10.

Image: This true color mosaic of Jupiter was constructed from images taken by the narrow angle camera onboard NASA’s Cassini spacecraft on December 29, 2000, during its closest approach to the giant planet at a distance of approximately 10 million kilometers. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

Launched on August 5, 2011, Juno completed its first year in Jupiter orbit on July 4, a reminder of how well shielded its instruments are in this tough environment. Rick Nybakken is project manager for Juno from JPL:

“The success of science collection at Jupiter is a testament to the dedication, creativity and technical abilities of the NASA-Juno team. Each new orbit brings us closer to the heart of Jupiter’s radiation belt, but so far the spacecraft has weathered the storm of electrons surrounding Jupiter better than we could have ever imagined.”

Indeed. Data collection from the Great Red Spot, a centuries-old, 16,000-kilometer wide storm, will be part of the spacecraft’s sixth science flyby, with perijove (the closest point in the orbit to Jupiter’s center) occurring on July 10 at 0955 EDT (1355 UTC). At this point, Juno will be about 3500 kilometers above the cloud tops. Less than 12 minutes later, the spacecraft will have moved directly above the huge storm, passing about 9000 kilometers above the Great Red Spot’s clouds, with all eight instruments as well as the JunoCam imager active.

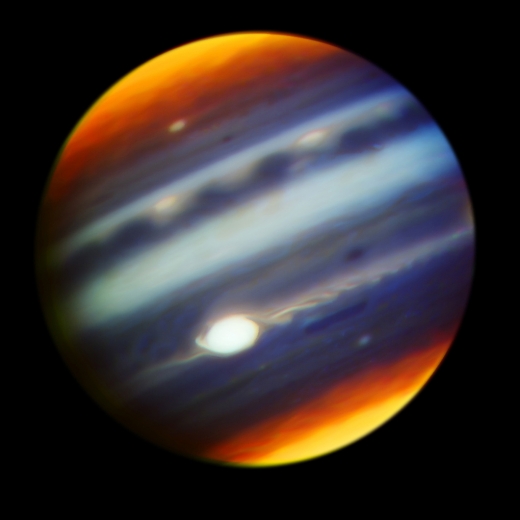

Earth-based telescopes have provided continuing observations of Jupiter in coordination with Juno, and on May 18, 2017, both the Gemini North and Subaru telescopes (both on Mauna Kea) simultaneously studied the planet in high resolution at different wavelengths, helping to provide data on atmospheric dynamics at various depths at the Great Red Spot and other regions of Jupiter. The image below was taken at infrared wavelengths, where the Great Red Spot appears brightest and high-altitude clouds and hazes become strikingly evident.

Image: This composite, false-color infrared image of Jupiter reveals haze particles over a range of altitudes, as seen in reflected sunlight. It was taken using the Gemini North Telescope’s Near-InfraRed Imager (NIRI) on May 18, 2017, in collaboration with the investigation of Jupiter by NASA’s Juno mission. Juno completed its sixth close approach to Jupiter a few hours after this observation. Credit: Gemini Observatory/AURA/NASA/JPL-Caltech.

You can see a prominent wave pattern north of the equator, with two bright ovals that are anticyclones that appeared in January of this year. Both are evidently an indication of an upsurge in storm activity that has been observed in these latitudes in 2017. Another bright anticyclonic oval can be seen further north. And note the hook-like shape on the left side of the Great Red Spot, an indication of intense winds stretching out atmospheric features. More traces of this wave-like flow pattern can be seen sweeping off its eastern (right) side.

“Observations with Earth’s most powerful telescopes enhance the spacecraft’s planned observations by providing three types of additional context,” said Juno science team member Glenn Orton of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. “We get spatial context from seeing the whole planet. We extend and fill in our temporal context from seeing features over a span of time. And we supplement with wavelengths not available from Juno. The combination of Earth-based and spacecraft observations is a powerful one-two punch in exploring Jupiter.”

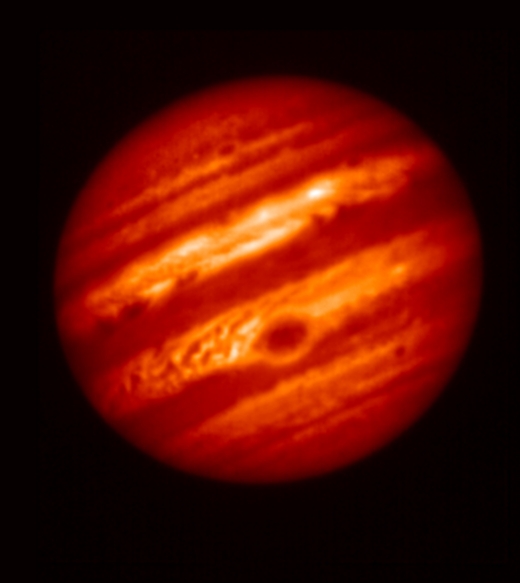

Image: This false-color image of Jupiter was taken on May 18, 2017, with a mid-infrared filter centered at a wavelength of 8.8 microns, at the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, in collaboration with observations of Jupiter by NASA’s Juno mission. The selected wavelength is sensitive to Jupiter’s tropospheric temperatures and the thickness of a cloud near the condensation level of ammonia gas. Credit: NAOJ/NASA/JPL-Caltech.

174P/Echeclus: Focus on an Unusual Centaur

Centaurs are intriguing objects, and not just because of the problem in figuring out what they are. For one thing, the farthest points in their orbits take them between the orbits of the outer planets in our Solar System. That makes them unstable, yielding lifetimes on the order of a few million years. They also show characteristics of both asteroids and comets, which makes objects like 174P/Echeclus so intriguing. Discovered in 2000, it was classified as a minor planet before a cometary coma appeared. Thus its current cometary designation.

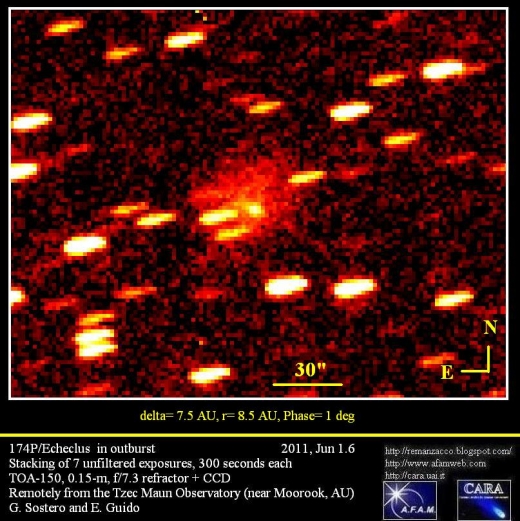

So what exactly do we have here? In 2005, a large piece of 174P/Echeclus broke off, possibly the result of an impact or, despite a distance at the time of over 13 AU from the Sun, perhaps the release of volatiles. We saw another outburst in 2011 at a distance of 8.5 AU from the Sun. Maria Womack (University of South Florida), who is lead author of a new paper on Echeclus, calls it “a bizarre solar system object,” which sounds about right, though other Centaurs — 2060 Chiron and 166P/NEAT — display comas reminiscent of those in comets.

Image: 174P/Echeclus in outburst mode in June of 2011. Credit: G. Sostero/E. Guido. Found at Guido’s excellent Comets & Asteroids site.

That Centaurs are odd objects is further confirmed by the largest confirmed member of their class, 10199 Chariklo, big enough at 260 km in diameter to be a mid-sized asteroid, and known to have a system of rings. We don’t see any comet-like activity here, but two other Centaurs — 52872 Okyrhoe and 2012 CG — have produced what may have been coma activity in the past. Will any Centaur that moves into the inner system become a comet?

For that matter, why do objects like these produce large, observable emissions while still far from the Sun? The average comet, often rich in frozen volatiles like carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, hydrogen cyanide and methanol, loses ice through sublimation and produces jets of water vapor and other gases only as it approaches the inner system. Perhaps one reason for the difference, the researchers learned, has to do with the composition of Centaurs.

What Womack and team found at Echeclus is that the object shows levels of carbon monoxide nearly 40 times lower than we would expect from comets at similar distances from the Sun. The implication is that this makes Echeclus, and by implication other Centaurs, more fragile than the average comet. The reason for the deficiency of carbon monoxide is unknown, though it may relate to physical processes that caused the CO to be lost.

The researchers used the Arizona Radio Observatory 10-m Submillimeter Telescope to search for CO at Echeclus in mid-2016, when the Centaur was 6.1 AU from the Sun. They found a production rate of carbon monoxide — Q(CO) — which turned out to be the lowest found in any Centaur, and 5 times lower than the carbon monoxide production found near aphelion. The same CO deficiency shows up in other Centaurs. The quoted segment from the paper below refers to Comet Hale-Bopp and the Centaur 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 (29P) for comparison:

Our data are consistent with Echeclus being a CO-deficient body, when comet Hale-Bopp’s data at ? 6 au is used as a proxy for a relatively unprocessed nucleus. When scaled by surface area and compared with CO measurements from other Centaurs, we see that specific production rates, Q(CO)/D2, from Echeclus and Chiron are ? 10-50 times below that of Hale-Bopp, and 29P, which are both known to be CO-rich.

But Centaurs will not yield their secrets easily. As the paper continues, we learn that CO deficiency is not a completely shared characteristic:

The lower CO output of Echeclus and Chiron may mean that they incorporated less CO into their nuclei than many other comets, or they may have lost a significant amount due to devolatilization while in their relatively close-to-the-Sun Centaur orbits. It is puzzling why 29P, another Centaur, is evidently CO-rich. Although no other CO detections exist for other Centaurs, stringent upper limits to their specific production rates show that several other Centaurs are also notably absent of CO outgassing, including Chariklo, 8405 Asbolus, 34842 and 95626.

Then bear in mind that we have evidence for fragments, rings and ring arcs around not just 10199 Chariklo but 29P, 2060 Chiron and Echeclus itself. Thus, as the paper points out, we need to make more measurements of CO production rates and fragmentation activity in other Centaurs to refine our models of their structure. The outer Solar System once again reminds us that our categories for these distant objects are subject to continuing revision.

“These are minor bodies that we are studying, but they can provide major insights,” says Gal Sarid (University of Central Florida), a co-author of the paper. “We believe they are rich in organics and could provide important hints of how life originated.”

The paper is Wierzchos, Womack & Sarid, “Carbon Monoxide in the Distantly Active Centaur (60558) 174P/Echeclus at 6 au,” Astronomical Journal Vol. 153, No. 5 (2017). Abstract.

M-Dwarf Habitability: New Work on Flares

The prospects for life around M-dwarf stars, always waxing and waning depending on current research, have dimmed again with the release of new work from Christina Kay (NASA GSFC) and colleagues. As presented at the National Astronomy Meeting at the University of Hull (UK), the study takes on the question of space weather and its effect on habitability.

We know that strong solar flares can disrupt satellites and ground equipment right here on Earth. But habitable planets around M-dwarfs — with liquid water on the surface — must orbit far closer to their star than we do. Proxima Centauri b, for example, is roughly 0.05 AU from its small red host (7,500,000 km), while all seven of the TRAPPIST-1 planets orbit much closer than Mercury orbits the Sun. What, then, could significant flare activity do to such vulnerable worlds?

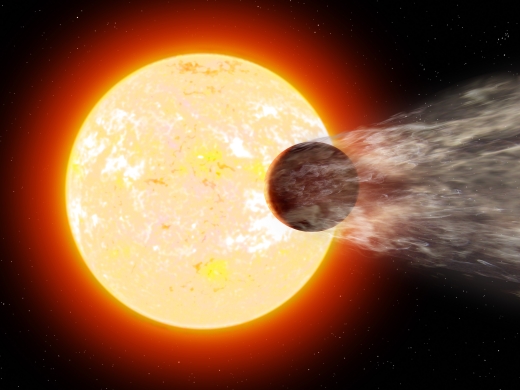

Image: Artist’s impression of HD 189733b, showing the planet’s atmosphere being stripped by the radiation from its parent star. Credit: Ron Miller.

Working with Merav Opher and Marc Kornbleuth (both at Boston University), Kay has homed in on coronal mass ejections (CMEs), the vast upheavals that throw stellar plasma into nearby space. While red dwarf stars are significantly cooler than our G-class Sun, their CMEs are thought to be far stronger because of their enhanced magnetic fields. From the paper:

Stellar activity tends to increase with the size of the stellar convection envelope (West et al. 2004) and stellar rotation rates (Mohanty et al. 2002; West et al. 2015), although the activity saturates for sufficiently high rotational velocity (Delfosse et al. 1998). For mid- to late-type M dwarfs (M4 to M8.5) the activity saturates at higher rotational velocities than for early-type M dwarfs, and above M9 the activity levels decrease significantly (Mohanty et al. 2002). Accordingly, most M dwarf stars will have significantly enhanced stellar activity as compared to the Sun.

A strong planetary magnetic field could counteract at least some of the resulting flare activity, but even there a possibility of strong erosion of the atmosphere remains. And if the planet is tidally locked, some recent work suggests little to no magnetic field can be expected.

The paper outlines the process when a CME hits a nearby planet. One problem is extreme ultraviolet and X-ray flux (XUV) which can heat the upper atmosphere and perhaps ionize it. If such radiation gets through to the surface, it can damage any potential life-forms there. While it turns out that an M-dwarf habitable zone planet receives an order of magnitude less XUV flux than Earth when the star is quiet, the flux jumps as high as 100 times Earth’s during the star’s frequent flare activity.

Significant CME activity also makes the planet much less likely to retain its atmosphere as a shield for life on the surface. A CME compresses whatever magnetosphere the planet has, and in extreme cases, say the authors, can exert enough pressure to shrink the magnetosphere to the point where the atmosphere can be seriously eroded.

Modeling an Astrospheric Current Sheet

Kay’s team modeled the effects of theoretical CMEs on the red dwarf V374 Pegasi, using a tool Kay developed for CME modeling called ForeCAT. They found that the strong magnetic fields of the star produce CMEs that can reach the so-called Astrospheric Current Sheet, where the background magnetic field is at its minimum. The same effect occurs with our Sun, when solar CMEs are deflected by magnetic forces toward the minimum magnetic energy.

At the Sun, the Heliospheric Current Sheet — the local analog to a different star’s Astrospheric Current Sheet — is a field that extends along the Sun’s equatorial plane in the heliosphere and is shaped by the effect of the Sun’s rotating magnetic field on the plasma in the solar wind. The HCS separates regions of the solar wind where the magnetic field points toward or away from the Sun.

Let’s dwell on that for a moment. Here’s what a NASA fact sheet has to say about the Heliospheric Current Sheet:

The sun’s magnetic field permeates the entire solar system called the heliosphere. All nine planets orbit inside it. But the biggest thing in the heliosphere is not a planet, or even the sun. It’s the current sheet — a sprawling surface where the polarity of the sun’s magnetic field changes from plus (north) to minus (south). A small electrical current flows within the sheet, about 10?10 A/m². The thickness of the current sheet is about 10,000 km near the orbit of the Earth. Due to the tilt of the magnetic axis in relation to the axis of rotation of the sun, the heliospheric current sheet flaps like a flag in the wind. The flapping current sheet separates regions of oppositely pointing magnetic field, called sectors.

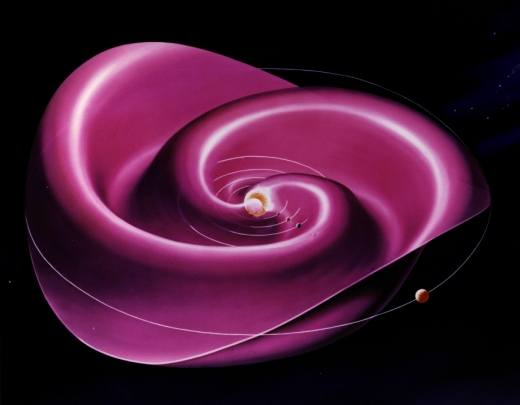

Image: The Heliospheric Current Sheet results from the influence of the Sun’s rotating magnetic field on the plasma in the interplanetary medium (solar wind). The wavy spiral shape has been likened to a ballerina’s skirt. The new work uses a software modeling package called ForeCAT to study interactions between CMEs and the Astrospheric Current Sheet around the red dwarf V374 Pegasi. Credit: NASA GSFC.

Kay and team have modeled the Astrospheric Current Sheet expected to be found around M-dwarfs like V374 Pegasi. The authors find that upon reaching the ACS, CMEs become ‘trapped’ along it. Planets can dip into and out of the ACS as they orbit. A CME moving out into the Astrospheric Current Sheet around an M-dwarf can cancel out a habitable zone planet’s local magnetic field, opening the world to devastating flare effects. The upshot:

We expect that rocky exoplanets cannot generate sufficient magnetic field to shield their atmosphere from mid-type M dwarf CMEs… We expect that the minimum magnetic field strength will change with M dwarf spectral type as the amount of stellar activity and stellar magnetic field strength change, and that early-type M dwarfs would be more likely to retain an atmosphere than mid or late-type M dwarfs.

The authors calculate that a mid-type M-dwarf planet would need a minimum planetary magnetic field between tens to hundreds of Gauss to retain an atmosphere, values that are far higher than Earth’s (0.25 to 0.65 gauss). CME impacts as numerous as five per day could occur for planets near the star’s Astrospheric Current Sheet. The only mitigating factor is that the rate decreases for planets in inclined orbits. The paper notes:

The sensitivity to the inclination is much greater for the mid-type M dwarf exoplanets due to the extreme deflections to the Astrospheric Current Sheet. For low inclinations we find a probability of 10% whereas the probability decreases to 1% for high inclinations. From our estimation of 50 CMEs per day, we expect habitable mid-type M dwarf exoplanets to be impacted 0.5 to 5 times per day, 2 to 20 times the average at Earth during solar maximum. The frequency of CME impacts may have significant implications for exoplanet habitability if the impacts compress the planetary magnetosphere leading to atmospheric erosion.

So we have much to learn about M-dwarfs. In particular, how accurate is the ForeCAT model in developing the CME scenario around such stars? As we examine such modeling, we have to keep in mind that magnetic field strength will change with the type of M-dwarf we are dealing with. Based on this research, only early M-dwarfs are likely to maintain an atmosphere.

The paper is Kay, Opher and Kornbleuth, “Probability of CME Impact on Exoplanets Orbiting M Dwarfs and Solar-Like Stars,” accepted at the Astrophysical Journal (preprint).