Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Niku: A ‘Rebellious’ Trans-Neptunian Object

We’ve all come to terms with the fact that beyond the orbit of Neptune there exists a large number of objects. These trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) substantially altered the almost sedate view of the Solar System that prevailed in the first half of the 20th Century, showing us that far from being a tame and orderly place of planets, asteroids and comets, we were in a system filled with material left over the the system’s formation. Tame and orderly became ragged and unkempt, and it was clear that the outer system was a place ripe for discovery.

Pluto was the first TNO to be discovered, all the way back in 1930, but the modern era of trans-Neptunian objects began in 1992 with the discovery of (15760) 1992 QB, and we can now count over 1750 TNOs, as listed by the Minor Planet Center. Bear in mind that we can divide the entire space occupied by TNOs into several prominent divisions: the Kuiper Belt, the Oort Cloud, and the scattered disk, with a few outliers like Sedna causing continuing controversy.

Image: Artist’s impression of a trans-Neptunian object. Credit: © NASA, ESA, and G. Bacon (STScI).

Which gets us to another controversial object, an unusual world its discoverers have named Niku. Probably less than 200 kilometers in diameter, Niku’s outstanding characteristic is that its orbital plane is tilted 110 degrees to the plane of the Solar System. The object is in a retrograde orbit, moving around the Sun in a direction opposite to the rest of the planets. We have one other TNO that fits the retrograde classification: 2008 KV42.

The paper on Niku, produced by Ying-Tung Chen (Academia Sinica, Taipei) and colleagues points out that 2008 KV42 has previously been the subject of dynamical simulations that show its orbit has a lifetime stable for billions of years. The researchers believe the Kuiper Belt is an unlikely origin for such a retrograde object, which may implicate the Oort Cloud, but the orbital dynamics of this population of objects await a good deal of further work.

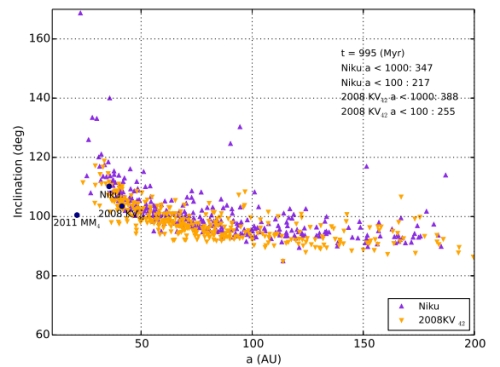

Discovered as part of the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System 1 Survey (Pan-STARRS 1) in Hawaii, Niku is another indication that something is preserving the orbits of these objects. The team’s simulations — using 1000 clones and moving them forward for a period of one billion years — show stable orbits matching the location of Niku and 2008 KV42, hence indicating the possibility of a large population with similar origins.

Image: The orbital distribution of survivors from 1000 initial clones of Niku (purple) and 2008 KV42 (orange) after 1 Gyr approximately. The overall clones decay far more slowly than normal Centaurs, with > 30% of the test particles remaining dynamical stability at the end of a 1 Gyr integration. Note that the orbits of Niku and 2008 KV42 are located at the highest density position in this plot. Credit: Chen et al.

What would cause clustering in the orbits of known objects with highly inclined orbits? To make sense of it, the team turned to known high-inclination objects from the Minor Planet Center catalog, selecting them according to criteria drawn loosely from their simulations. We have a small number of samples — the team was working with only six objects. Even so, the probability of getting six objects into a common plane is low enough to argue against coincidence. And because orbital precession should prevent long-term clustering, the authors assume that another mechanism has to explain it. Planet Nine immediately comes to mind, the hypothesized world that may lurk in the Solar System’s outer reaches. Evidence for Planet Nine, after all, comes from a similar group of objects in highly inclined orbits.

But a hypothetical Planet Nine, an undiscovered dwarf planet in the scattered disk, and a distant solar companion all fail when subjected to the team’s analysis. To explain the observed clustering requires some kind of mechanism that remains undiscovered. In the quotation from the paper below, ? refers to the longitude of the ascending node, one of the orbital elements used to specify key orbital parameters. It is here that the clustering is observed:

…we established through numerical integrations that the putative Planet Nine was unable to explain the orbital confinement. In addition, we also attempted more extreme alternative scenarios, consisting of integrations that include a synthetic high-inclination dwarf planet of a few Earth masses whose orbit crosses the giant planet region. None of these attempts succeeded in anchoring the ? of the test particles. Moreover, adding a planet into planet-crossing region has a very high chance of disrupting the orbital structure of the Kuiper Belt and remaining outer Solar System.

Niku’s orbit is a mystery — no wonder its name means ‘rebellious’ in Chinese. We could use a lot more data on objects like Niku to help us understand their apparently long-lived orbital plane and the factors that keep it stable. The authors point to projects like the upcoming Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) survey that will perform a ten-year scan producing a 200 petabyte set of images beginning in 2022. We can hope the LSST survey will uncover whatever object or objects are responsible for sculpting the orbits of these high-inclination TNOs.

The paper is Ying-Tung Chen et al., “Discovery of A New Retrograde Trans-Neptunian Object: Hint of A Common Orbital Plane for Low Semi-Major Axis, High Inclination TNOs and Centaurs,” accepted at Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint).

Evening Landscape with Exomoons

I often work out my thoughts on the topics we discuss here while taking long walks. I try to get in five miles a day but more often it’s about three. In any case, these long, reflective walks identify me as the neighborhood eccentric, an identity that is confirmed by the things I write about. What’s interesting about that is that so many people have a genuine interest in the stars and how we might get there. Some of the best questions I’ve ever had have been from people whose interest is casual but persistent, and one good question usually leads to another.

Hence I wasn’t surprised on yesterday’s walk to find myself talking with a neighbor about exomoons and why we study them. After all, we have a Solar System in which moons are commonplace. Isn’t it perfectly obvious that different solar systems would have planets with moons?

The answer is yes, but it also follows that things that seem perfectly obvious still have to be confirmed. But let’s unpack it a bit more than that. We’re familiar with our own system’s configuration, in which moons of astrobiological interest are orbiting gas giants a long way from the inner system. But we know from our exoplanet work that large planets like these can exist in warmer places. Thus the notion of habitable moons around gas giants, or perhaps double planets in the habitable zone, something like a larger version of Pluto and Charon in a comfortable orbit.

Popular films like Avatar keep the exomoon theme in front of the public, whose interest is understandable. After all, could anything be more exotic than a warm gas giant orbited by something a bit like the Earth? From an astrobiological perspective, the thought of Europa or Titan analogs in warm orbits is thrilling, a reminder that life may have gained many footholds in the galaxy. The Hunt for Exomoons with Kepler project is all about figuring out the occurrence rate of large moons so we can learn whether such moons are common.

The other aspect of exomoon detection has to do with increasing our expertise. It wasn’t so long ago that we had yet to detect our first exoplanet. Now we’re delving into planetary atmospheres and working out the orbital dynamics of multi-planet systems. An exomoon detection would be a major proof of concept, demonstrating the growth of our skills. It would also begin to build an exomoon catalog that will help us understand how important exomoons may be to planetary habitability. How big a role does our own moon play in keeping our planet habitable?

There’s also plenty to learn about how planetary systems form in the first place. We now think our Moon formed in a massive collision (the Big Whack) with a Mars-sized object in the early days of our planet’s history. How likely an event is this, and how often does it happen in other Solar Systems? We still have a lot to learn about how the satellite systems around various planets emerge, especially when we consider the wild variety of moons we see in our Solar System. Building the exomoon catalog will help answer these questions.

The Joys of Beta Pictoris b

I hadn’t planned to get into exomoons today, but serendipity struck. After yesterday’s conversation I ran across Phil Plait’s latest essay for Slate. The popular astronomer and science popularizer (author of Death from the Skies! and, of course, Bad Astronomy), now explains that because of an unusual alignment beginning in 2017, we may be able to detect an exomoon, if there is one, around the planet Beta Pictoris b.

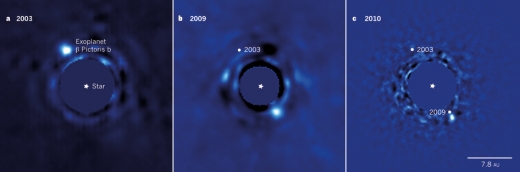

We’re dealing with a system far different from our own. Some 60 light years away, the star Beta Pictoris is more massive than the Sun and a mere infant, at 25 million years old, compared to our own star (around 4.5 billion years). This is a solar system in formation. Moreover, it has been under intensive study since scientists realized it was surrounded by a large circumstellar disk. The planet Beta Pictoris b was first imaged in 2003, a world more massive than Jupiter that orbits its host every 20 years. You can see its movement in the time-spaced images below.

Image: Infrared images of the planet ? Pictoris b obtained in 2003 (a), 2009 (b) and 2010 (c), showing the planet’s movement in an orbital plane that is nearly edge-on as seen from Earth. The host star is in the central part, but its light has been suppressed to show the fainter planet. The white dots in b and c denote previous positions of the planet. Faint blobs are optical effects. It is not possible to tell from these images whether the planet is orbiting towards or away from us, but {Ignas] Snellen and colleagues’ spectroscopic observations clearly indicate that the planet is currently in a part of its orbit where it is moving towards us. Credit: ESO.

Note in the description above that the planet’s orbital plane is close to edge-on from our perspective. It’s not close enough to make a transit possible, but what Plait talks about is

the next best thing. Drawing on a paper by Jason Wang (UC-Berkeley) and colleagues, Plait explains that the region around the planet called its Hill Sphere will pass in front of the star from our perspective. The Hill Sphere is the area around an astronomical body in which its gravity dominates. In other words, within the Hill Sphere, a moon could be retained by the planet.

Nobody explains such concepts as well as Phil Plait, so I’ll give him the floor here, drawing directly from his essay:

The size of the sphere depends on the mass of the planet, the mass of the star, and the distance between them. For example, the Earth’s Hill sphere reaches out to about 1.5 million kilometers. The Moon, orbiting 380,000 km away, is well inside that, so its motion is mostly influenced by the Earth (some people like to say the Moon orbits the Sun more than it does the Earth, but those people are wrong). Weirdly, Pluto’s Hill sphere is much larger than Earth’s, but that’s because it’s so far from the Sun that an object can orbit Pluto from farther away and still be heavily influenced by it.

What emerges with regard to Beta Pictoris b is that its Hill Sphere is 160 million kilometers in radius. We get no transit of the star by the planet itself, but by August of 2017, the planet will be at its closest approach to the star and the Hill Sphere region will transit. We’ll be able to look for debris or exomoons. A large moon passing in front of the star would be the first entry in the exomoon catalog.

But even if we get no exomoon detection, bear in mind that we may make other interesting observations. This young planet is still being born, and it may well contain a circumplanetary disk of its own, or even a ring system that is the residue of planet formation. “The transit of ? Pic b’s Hill sphere,” Wang et al. write, “should be our best chance in the near future to investigate young circumplanetary material.” We’ll also learn a lot more about how Beta Pictoris b perturbs the circumstellar disk, a window into early solar system formation.

All this is good material for my next walk and the conversations sure to follow. The paper is Wang et al., “The Orbit and Transit Prospects for ? Pictoris b constrained with One Milliarcsecond Astrometry,” accepted at the Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

Liquid Methane in Titan’s Canyons

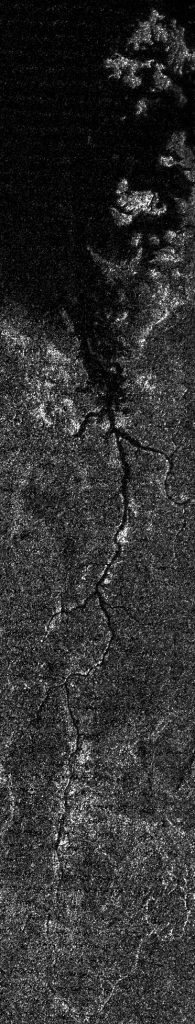

It was in 2012 that Cassini data showed us the presence of the river system now called Vid Flumina, which empties into Titan’s Ligeia Mare after a journey of more than 400 kilometers. Given surface temperatures on this largest of Saturn’s moons, researchers assumed liquid methane would be the key player here. The question was whether the river — and the eight canyons that branched off from it along its course — were still filled with liquid or long dry.

Now we have the answer, thanks to new work from Valerio Poggiali (La Sapienza University, Rome) and colleagues. Using radar signals bounced off Titan’s surface in May of 2013, the researchers probed the deep gorges near Titan’s north pole and were able to distinguish rocky material from smooth liquid. We’re clearly looking at a surface that is actively eroding, one with striking comparisons to the landscapes of Utah and Arizona as well as the Nile River gorge.

Key to the work here is the use of Cassini’s radar as an altimeter, measuring the height of features on the surface. Poggiali and team were able to use the altimetry data in combination with previous radar imagery of the area to analyze the Vid Flamina channels. Radar returns from the channels are highly reflective, producing a telltale glint, and the radar backscatter in relation to nearby terrain implicates smooth surfaces. From the paper:

…we interpret these smoothness constraints as requiring liquid surfaces. This represents the first direct detection of liquid-filled channels on Titan. Furthermore, channels exhibit canyon-like morphology, with the liquid surface elevations of the higher-order tributaries of the Vid Flumina network…occurring at the same elevation as Ligeia Mare. We also find lower order tributaries with liquid surface elevations above the level of Ligeia Mare, consistent with elevated tributary networks feeding into the main channel system.

The canyons branching off from Vid Flumina are less than a kilometer wide, with walls as high as 570 meters. They were likely carved by the liquid methane as it drained into Vid Flumina, a process we see on Earth in the shaping of river gorges. These are steep walls, rising as sharply as 40 degrees. What remains unknown is the age of the processes at work here, and the depth of the liquid methane. What we can assume is that the presence of liquid in these canyons reflects a process of canyon formation that is ongoing on this active geological surface.

Image: Liquid methane and ethane flowing through Vid Flumina, a 400-kilometer long river often compared to Earth’s Nile River, is fed by canyon channels running hundreds of meters deep. Credit: NASA, JPL-Caltech, Agenzia Spaziale Italiana.

Such steep clefts in Titan’s landscape could be the result of several processes including terrain uplift and changes in sea level. This JPL news release draws comparisons with the Grand Canyon, where rising terrain caused the Colorado River to cut deeply into the landscape below over a timespan of several million years. But canyons formed from changes in water level are also found on Earth, as is evident at Lake Powell, a reservoir that straddles the border between Arizona and Utah. Here, the Colorado’s rate of erosion increases when the water level in the reservoir drops. On Titan, both process may be in play.

“It’s likely that a combination of these forces contributed to the formation of the deep canyons,” says Poggiali, “but at present it’s not clear to what degree each was involved. What is clear is that any description of Titan’s geological evolution needs to be able to explain how the canyons got there.”

Image: NASA’s Cassini spacecraft pinged the surface of Titan with microwaves, finding that some channels are deep, steep-sided canyons filled with liquid hydrocarbons. One such feature is Vid Flumina, the branching network of narrow lines in the upper-left quadrant of the image. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI.

We have other channels to study on Titan, and many may be hidden below the resolution of the Cassini instruments. But bear in mind as well that when the Cassini mission ends on September 15 of next year, we will have used its radar in imaging mode to cover a total area of 67 percent of the surface. That’s a triumph for the mission, but also a reminder of how much we leave unseen. No matter how successful the mission, it always points to what needs study next.

The paper is Poggiali et al., “Liquid-filled canyons on Titan,” published online by Geophysical Research Letters 9 August 2016 (abstract).

Stromatolites: Astrobiological Implications

Oil companies involved in astrobiology? It doesn’t seem likely, but in a roundabout way, it’s true. A consortium including Chevron, Repsol, BP and Shell have a natural interest in developing better models for subsurface reservoirs and source rocks in microbe-rich carbonate environments. At the same time, NASA’s Astrobiology Program is intrigued with how we could find bacterial structures on other worlds, and their role in planetary habitability.

The result: Both Big Oil and NASA are supporting research into stromatolites, the calcium-carbonate rock structures built up by lime-secreting bacteria (technically, cyanobacteria, that draw their energy from photosynthesis). We can probe ancient life on Earth by studying these accreted structures, some of which go back more than 3.5 billion years.

Erica Suosaari works for Bush Heritage Australia, an organization involved in conservation and land management. The Hamelin Station Reserve in Western Australia borders a nature reserve with vast quantities of marine stromatolites. Suosaari’s work in the area, funded by the above sources, is encapsulated in a paper in Scientific Reports (citation below), as noted in an article in Astrobiology Magazine, from which this:

“Looking for evidence of life in the rocks is like finding a needle in the haystack,” wrote Suosaari in an e-mail. “If stromatolites have definitive bio-signatures — such as self organized morphologies that are indicative of life processes — then it may be possible to look for that ‘signature’ in rocks on the surface of other planets and significantly reduce the size of that haystack.”

The Hamelin Pool Marine Nature Reserve offers stromatolites in extraordinary abundance, providing the opportunity to study analogs to the earliest such formations on Earth. Suosaari and team have discovered that modern stromatolites in their sample have created structures similar to stromatolites that emerged billions of years ago. The cyanobacteria that formed ancient stromatolites are believed to be the first organisms to use photosynthesis, with the significant side-effect of producing the oxygen so useful in the development of complex life.

Image: Modern stromatolites in Shark Bay, Western Australia. Credit: Paul Harrison (Reading, UK) using a Sony CyberShot DSC-H1 digital camera., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=714512

Is Hamelin Pool, then, a window into the early Earth? The processes at work here involve microbes that draw from the same lineage, with the same oxygen-producing result. What’s intriguing for research in the near-term is that it may be possible to transplant microbial communities like these to other places. Let me quote from the conclusion of the Astrobiology Magazine article:

Suosaari said she thought of stromatolites when reading about SpaceX founder Elon Musk’s plans to bring life to the planet Mars. She suggested that because these stromatolite-building microbial communities produce oxygen, they could potentially make the Red Planet more life-friendly.

“Obviously with Elon Musk’s plans, we don’t have billions of years to shape the atmosphere if he is planning to move life there in the coming years, and Mars has less than 1 percent of the atmosphere of Earth,” she acknowledged. “But I begin to think about photosynthesizing microbial mats and how they have prevailed for billions of years; it’s a kind of resilience and longevity that our species hasn’t yet achieved. Perhaps we should look to these microbial communities to generate oxygen on the Red Planet at a small scale.”

An intriguing thought, as is the idea that fossil evidence of life on far more distant exoplanets may eventually tell our probes something about how life took hold there. In the case of Earth-based stromatolites, we see microbial mats that colonize the surface of the structure, mats that vary according to where the stromatolite is situated in the tidal zone. Consider the stromatolite as a record of previous surface mats, while the shapes of the various kinds of stromatolite relate to differing conditions in the broader pool.

This is an evidently global record, if we can learn to read it. Note this from the paper:

New insights regarding stromatolite growth in Hamelin Pool present opportunities for comparative sedimentological research advancing understanding of early Earth. The diversity of morphologies in the eight Stromatolite Provinces… provides a unique opportunity for investigating environmental and/or biological processes determining stromatolite morphology…. Of particular note, previously unreported, elongate nested subtidal structures of Spaven Province are remarkably similar to 1.9 billion year old longitudinal stromatolites at Great Slave Lake, Northwest Territories.

Could we find structures like these on distant planets? I’m reminded of the enigmatic ‘stolid, dark tower images’ returned to Earth by AXIS, a probe sent by a future Earth to Alpha Centauri B in Greg Bear’s Queen of Angels (1990). The AXIS data convince some that an intelligent life-form must have created the towers, but later the view shifts:

“The only news we have from AXIS may or may not be significant. A recently received analysis shows that at least three of the circular tower formations discovered by AXIS on Alpha Centauri B-2 are made up of mixes of minerals and organic materials, the minerals being calcium carbonate and aluminum and barium silicates, and the organic materials being amorphous carbohydrate polymers similar to cellulose found in terrestrial plant tissue. AXIS has told its Earth-based maters that, in its opinion, the towers may not be artificial structures…”

With knowledge of life’s development limited to our own planet, we can’t yet know what kind of structures are implicated in the development of life elsewhere, allowing habitable conditions to gradually develop. But we may eventually find structures just as rich in their own way as the stromatolites at the Hamelin Pool Marine Nature Reserve, and as enigmatic as the formations the orbiting AXIS probe investigates from its perch high above a habitable Centauri planet.

The paper is Suosaari et al., “New multi-scale perspectives on the stromatolites of Shark Bay, Western Australia,” published online by Scientific Reports 3 February 2016 (full text).

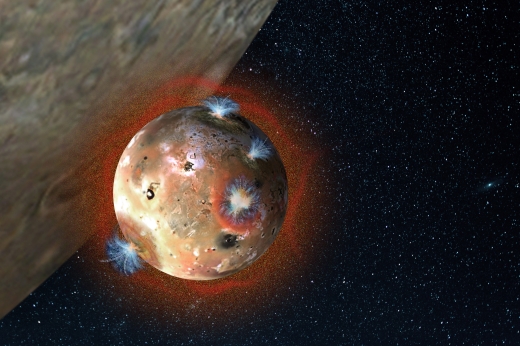

Atmospheric Collapse on Io

I suspect most scientists would like to have a moment like the one Stanton Peale, Patrick Cassen and Ray Reynolds experienced when Voyager flew past Io in 1979. How many of us get to see a major idea vindicated in such short order? It was on March 5 that Voyager 1 passed within 22,000 kilometers of Io. A scant three days before, Peale, Cassen and Reynolds had published their prediction that tidal forces should keep the moon’s interior roiling, resulting in volcanic activity. Linda Morabito, on the Voyager navigation team, analyzed Voyager imagery shortly thereafter to discover that volcanoes were indeed active on the surface.

What a triumph for the power of thorough analysis and prediction. Voyager, in fact, found nine plumes on Io, while demonstrating that its surface was dominated by sulfur and sulfur dioxide frost, with extensive lava fields extending for hundred of kilometers. The moon was also observed to have a thin atmosphere consisting primarily of sulfur dioxide.

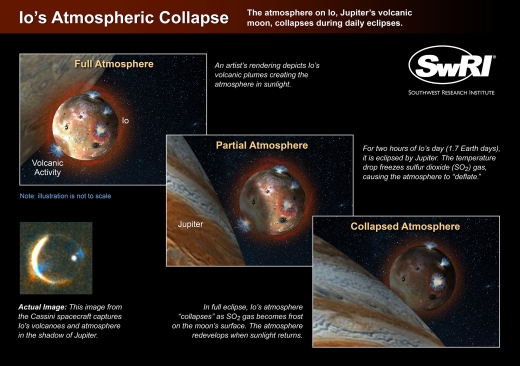

That thin envelope is now the subject of a new paper from Constantine Tsang (SwRI) and colleagues. We learn that gas emitted from Io’s volcanoes freezes onto the surface when Jupiter moves between Io and the Sun. Sublimation re-creates the atmosphere when sunlight returns.

Image: An artist’s rendering depicts the atmosphere on Io, Jupiter’s volcanic moon, as it collapses during daily eclipses. Credit: Southwest Research Institute.

This was the first time that atmospheric collapse and re-building on Io had been observed, a tricky procedure indeed. The scientists used the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii with the Texas Echelon Cross Echelle Spectrograph (TEXES). The latter is a high resolution mid-infrared spectrometer that was able to detect the heat signature of the atmospheric collapse.

Temperatures on Io’s surface drop from -145 degrees Celsius to -170 degrees C when a full eclipse occurs, followed by atmospheric collapse as the sulfur dioxide settles onto the surface. From the paper:

These observations provide the first direct evidence that Io’s primary molecular SO2 atmosphere collapses in eclipse, with SO2 condensing on the surface as SO2 frost. Our observations also allow us to constrain the spatial distribution of Io’s atmosphere. The fact that these observations show SO2 band depths decreasing until they almost disappear implies the atmosphere, at least on the hemisphere centered around 340° that is observed during eclipses, is global and not centered over volcanic hotspots; i.e., localized SO2 over active volcanoes is a minor component of the atmosphere on this hemisphere.

What we see is a moon whose tenuous atmosphere is in a continual cycle of collapse and restoration. It’s known that the volcanoes of Io are the source of the sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere, but we now have a demonstration of the power of sunlight to control atmospheric pressure as it changes the temperature of surface ice, resulting in the sublimation that rebuilds the atmosphere after an eclipse. This is a daily phenomenon on Io, where the day is 1.7 Earth days long, and an eclipse by Jupiter occurs for two hours out of every day.

Image (click to enlarge): Atmospheric collapse on Io in a series of images. Credit: Southwest Research Institute.

These findings are still a work in progress, for recent observations by the Hubble instrument have contradicted them by suggesting that Io’s atmosphere does not respond quickly to sunlight as the moon comes out of eclipse. There may, in other words, be longitudinal variations here. Where the atmosphere is thickest, emission from the volcanoes may mask the sublimation seen in the Gemini North data. It will take further observations to resolve the matter.

The paper is Tsang et al., “The Collapse of Io’s Primary Atmosphere in Jupiter Eclipse,” published online by the Journal of Geophysical Research 2 August 2016 (full text).

SETI, Astrobiology and Red Dwarfs

If you’ve been following the KIC 8462852 story, you’ll want to be aware of Paul Carr’s Dream of the Open Channel blog, as well as his Wow! Signal Podcast, both of which make for absorbing conversation. In his latest blog post, Carr offers sensible advice about how to look at anomalies in our astronomical data. Dysonian SETI tries to spot such anomalies in hopes of uncovering the activities of an extraterrestrial civilization, but as Carr makes clear, this is an enterprise that needs to be slowly and patiently done, without jumping to any unwarranted assumptions.

Let me quote Carr on this important point:

…we will have to be patient, since we will be almost certainly be wrong at first, or perhaps just unlucky in our search. We don’t need to nail it exactly, but we will need to develop rough models of ET activity that distinguishes it from nature. These models would more or less fit the data that we think anomalous, would make testable predictions, and would show how to rule out at least known natural phenomena. Such a family of models may be available next year, or it may be in 100 years, but the more anomalous data we have, the more the models can be constrained.

This paragraph gets it right, taking it as a given that we have no idea whether there are extraterrestrial civilizations or, for that matter, life of any kind around other stars. We certainly have no idea how widespread either form of life might be, and in the case of Dysonian SETI, we would be looking at technologies so far in advance of ours that recognizing them for what they are (or might be) creates myriad challenges. So while we try to distinguish natural phenomena from the possibility of intelligent activity, we need to keep these profound limitations in mind.

Tabby’s Star, then, is a wonderful case in point, certainly a motivator for this kind of research (and, as we’ve seen, one capable of being sustained at least modestly by public funding), but we should also consider it in a broader perspective. The goal will be to build a catalog of unusual phenomena that can be consulted as we begin to differentiate among such targets. We may discover that all of these can be accounted for by natural processes, and if so, then we have learned something valuable about the universe. No small accomplishment, that.

Red Dwarfs and Astrobiology

Looking beyond SETI to more fundamental questions of astrobiology, we find ourselves in that unsettling period when we have instruments in the pipeline that can tell us much about the exoplanets we observe, but we’re not yet receiving the data that can make a definitive call on the existence of life elsewhere. Astrobiology will accumulate data at increasingly fine levels of detail as we move from missions like Kepler to searches around closer stars. Meanwhile, we have to tune up our models for detecting biosignatures as we wait for the technology to test them.

Here the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) comes to mind, as does PLATO (PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars), and of course the James Webb Space Telescope. TESS is due for a 2017 launch, JWST for 2018 and PLATO for 2024. WFIRST (Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope), scheduled for the mid-2020s, is likewise going to provide key exoplanet observations, and let’s not neglect the small photometric platform CHEOPS (CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite), which will sharpen the target lists of future ground-based observatories. We need to continue refining our answers to this question: What does life do to a planet that offers a key observable, and what are the best instruments to detect it.

Red dwarfs make excellent targets if we’re studying a planetary atmosphere to learn whether or not there are biomarkers there, and now we have a new paper from Avi Loeb (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) that asks whether such stars may ultimately become home to the vast majority of cosmic civilizations. Working with Rafael Batista and David Sloan (both at Oxford University), Loeb acknowledges the obvious: We don’t know if stars like these can support life, and the authors call for building the datasets to find out. But if they can, then the implications are that most life in deep space will eventually be around such stars.

I say ‘eventually’ because M-dwarfs have lifetimes measured in the trillions of years, much greater than the 10 billion years or so that G-class dwarfs like our Sun can expect. And of course, around our own star life gets problematic within about a billion years. We have a planet that cannot be expected to remain habitable all the way to the last days of the Sun.

If life can form on planets around red dwarfs, then the probability of life grows much higher as we go further and further into the future, for these small stars are the most common kind of star in the galaxy, comprising as much as 80 percent of the stellar population. That would mean we are early to the dance, and a densely populated galaxy has simply not had time to develop. Loeb’s paper calculates the relative formation probability per unit time of habitable Earth-like planets within a fixed comoving volume of the Universe and finds red dwarfs favored:

“If you ask, ‘When is life most likely to emerge?’ you might naively say, ‘Now,'” says Loeb. “But we find that the chance of life grows much higher in the distant future.”

Image: This artist’s conception shows a red dwarf star orbited by a pair of habitable planets. Because red dwarf stars live so long, the probability of cosmic life grows over time. As a result, Earthly life might be considered “premature.” Credit: Christine Pulliam (CfA).

Hence the importance of a biosignature detection. If we find such markers in the atmosphere of a red dwarf, we have learned something not only about that particular star, but about the prospect of life in later cosmic eras up to the ten trillion year lifetime of the average red dwarf. The universe we see has had 13.7 billion years to produce life, but we can only imagine what kinds of life might emerge in the future. As for the probability of our own emergence, let me quote from the paper:

One can certainly contend that our result presumes our existence, and we therefore have to exist at some time. Although our result puts the probability of finding ourselves at the current cosmic time within the 0.1% level, rare events do happen. In this context, we reiterate that our results are an order of magnitude estimate based on the most conservative set of assumptions within the standard ?CDM model.

Conservative indeed, and if we tweak the assumptions, it gets more extreme:

If one were to take into account more refined models of the beginning of life and observers, this would likely push the peak even farther into the future, and make our current time less probable. As an example, one could consider that the beginning of life on a planet would not happen immediately after the planet becomes ‘habitable’. Since we do not know the circumstances that led to life on Earth, it would be more realistic to assume that some random event must have occurred to initiate life, corresponding to a Poisson process [in probability theory, used to model random points in time and space]. This would suppress early emergence and thus shift the peak probability to the future.

Are we truly premature, or are we simply going to learn that life is not possible around stars in an M-dwarf habitable zone? We’ve considered all the possibilities many times in these pages. Tidally locked to its star, a planet like this would experience constant day on one side, constant night on the other, with ramifications for climate and habitability that remain controversial. Extreme radiation from solar flares in young M-dwarfs may scour the surface of life (or, on the other hand, act as an evolutionary spur). And such planets may be home to volcanic activity that can lead to runaway greenhouse effects (see A Mini-Neptune Transformation?).

In other words, life’s chances around G-class stars may be profoundly greater than around M-dwarfs, in which case the chance of life emerging does not increase as we move into the distant future. For these reasons, using our upcoming space missions to search for life around small red stars can help us place ourselves in the cosmic hierarchy. We need to learn what conditions a planet in the habitable zone of an M-dwarf can support, and the discovery of biosignatures there would cause us to re-evaluate our thoughts on ‘average’ life and its existence around Sun-like stars.

The paper is Loeb, Batista and Sloan, “Relative Likelihood for Life as a Function of Cosmic Time,” accepted for publication in Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics (preprint). A CfA news release is also available. Ben Guarino writes up Loeb’s findings in a helpful essay for the Washington Post.