Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Alpha Centauri Planet Reconsidered

Finding a habitable world around any one of the three Alpha Centauri stars would be huge. If the closest of all stellar systems offered a blue and green target with an atmosphere showing biosignatures, interest in finding a way to get there would be intense. Draw in the general public and there is a good chance that funding levels for exoplanet research as well as the myriad issues involving deep space technologies would increase. Alpha Centauri planets are a big deal.

The problem is, we have yet to confirm one. Proxima Centauri continues to be under scrutiny, but the best we can do at this point is rule out certain configurations. It appears unlikely, as per the work of Michael Endl (UT-Austin) and Martin Kürster (Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie), that any planet of Neptune mass or above exists within 1 AU of the star. Moreover, no ‘super-Earths’ have been detected in orbits with a period of less than 100 days. This doesn’t rule out planets around Proxima, but if they are there, so far we don’t see them.

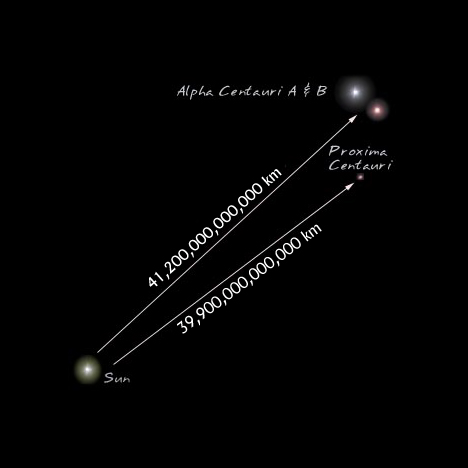

Image: The Alpha Centauri stellar system, consisting of the red dwarf Proxima Centauri and the two bright stars forming a close binary, Centauri A and B. Credit: NASA.

Centauri B, the K-class star in close proximity to G-class Centauri A, was much in the news a few years back with the announcement of Centauri Bb, a candidate world announced by Swiss planet hunters. This is radial velocity work based on data gathered by the HARPS (High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planetary Searcher) spectrometer on the 3.6-meter telescope at the European Southern Observatory in La Silla, Chile. The signal that Xavier Dumusque and team drew out of the data was 0.5 meters per second, a fine catch if confirmed.

What we thought we had in Centauri Bb was a mass just a little over the Earth’s and an orbit of a scant 3.24 days. As the blistering first planet detected around one of the Centauri stars, it would be a significant find even if it’s a long way from the temperate, life-sustaining world we’d like to find further out. The putative Centauri Bb supported the idea that there might be other planets there, and we’ve known since the work of Paul Wiegert and Matt Holman back in the 1990s that sustainable habitable zone orbits are possible around both the primary Alpha Centauri stars.

But Centauri Bb has remained controversial since Artie Hatzes (Thuringian State Observatory, Germany), using different data processing strategies, looked at the same data and found a signal he considered too noisy, indicating that what might be a planet might also be stellar activity on Centauri B itself. Debra Fischer’s team at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory has also been studying Centauri Bb using the CHIRON spectrometer but has not been able to confirm it. And while a transit search using the Hubble Space Telescope did find a promising lightcurve (about which more in a moment), it couldn’t confirm Centauri Bb.

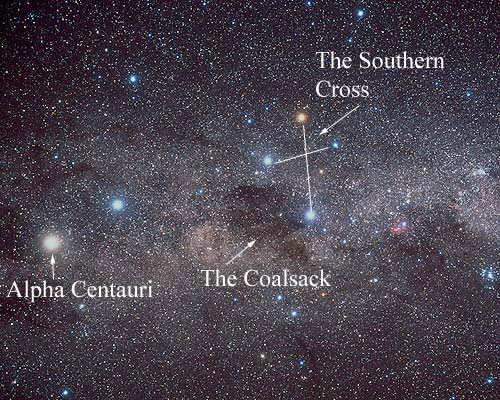

Image: Of the three stars of Alpha Centauri, the dimmest, Proxima Centauri, is actually the nearest star to the Earth. The two bright stars, Alpha Centauri A and B form a close binary system; they are separated by only 23 times the Earth – Sun distance. This is slightly greater than the distance between Uranus and the Sun. The Alpha Centauri system is not visible from much of the northern hemisphere. The image above shows this star system and other objects near it in the sky. Credit/copyright: Akira Fujii / David Malin Images.

Now we have a new paper from Vinesh Rajpaul (University of Oxford) and colleagues that makes Centauri Bb look more unlikely than ever. Rajpaul praises the thorough work of Xavier Dumusque and the team at the Geneva Observatory, but notes that their attempts to filter stellar activity out of their data evidently boosted other periodic signals that had nothing to do with a planet. The signal grows out of the time sampling, or ‘window function,’ of the data.

What is left behind is what the paper calls ‘the ‘ghost’ of a signal’ that was present all along. The paper argues that when a signal is sampled at discrete times (and the Dumusque team had to use the La Silla instrument only when it was not otherwise booked), periodicities can be imposed on the signal. Rajpaul was able to simulate a star with no planets, generating synthetic data out of which the exact same 3.24-day planetary signal emerged. The problem is particularly acute when working with planetary ‘signals’ as weak as these. From the paper:

D12’s data set [i.e., the data gathered by Dumusque and team] was particularly pathological because the window function happened to contain periodicities that coincided with the stellar rotation period of α Cen B, and its first harmonic; when these signals were filtered out, the significance of the 3.24 d signal was preferentially boosted.

All this is going to be quite useful if it helps us refine our techniques for identifying small planets. Rajpaul proposes that his team will carry out a new study of the spurious but coherent signals that can emerge from noisy datasets that should help us learn how to mitigate the problem:

We alluded to a number of other tests we believe worth carrying out when considering the reliability of planet detections from noisy, discretely-sampled signals. These include using the same model used to detect the planet instead to fit synthetic, planet-free data (with realistic covariance properties, and time sampling identical to the real data), and checking whether the ‘planet’ is still detected; comparing the strength of the planetary signal with similar Keplerian signals injected into the original observations; performing Bayesian model comparisons between planet and no-planet models; and checking how robust the planetary signal is to datapoints being removed from the observations.

Xavier Dumusque praises the Rajpaul team in this story in National Geographic, saying “This is really good work… We are not 100 percent sure, but probably the planet is not there.” We’re going to get a lot out of this investigation even though we lose Centauri Bb.

But back to that HST transit study run by Brice-Olivier Demory (University of Cambridge). I mentioned that it could detect no transit of Centauri Bb, which certainly fits with what we’ve just seen, but there was an interesting lightcurve suggesting a different possible planet, this one in an orbit that might range from 12 to 20 days. If this planet exists, radial velocity confirmation would be even more challenging than for Centauri Bb. Its signal, as Andrew LePage notes in The Discovery of Alpha Centauri Bb: Three Years Later, would be only half that of Centauri Bb.

LePage’s work at Drew ex Machina is definitive, and he has devoted a good deal of attention to Alpha Centauri. Here he explains why that second ‘planet’ is going to be so hard to spot:

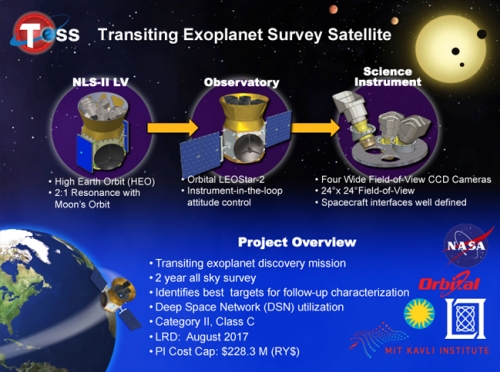

Unfortunately with such a poorly constrained orbit, three weeks of nearly continuous photometric monitoring of α Centauri B will be required to confirm this hypothesis. HST is too busy to accommodate a dedicated search of this length and no other space telescope currently available is capable of making the needed observations. In addition, since the radial velocity signature for this planet would be expected to be maybe half that of α Centauri Bb, this method has little likelihood of providing independent confirmation of this sighting any time soon. Once again, we will have to wait for a few more years for new telescopes to become available such as NASA’s TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) mission or ESA’s CHEOPS (Characterizing Exoplanets Satellite) which are both scheduled for launches in 2017 and may be capable of making the required observations of such a bright target.

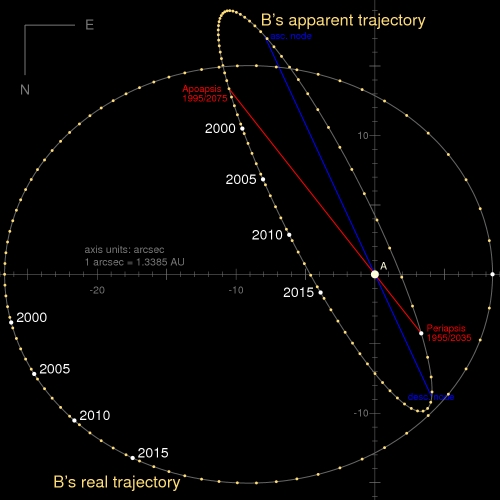

Alpha Centauri is frustrating in many ways because you would expect the closest stellar system to have revealed more of its secrets by now. One of the problems, though, and a huge one, is that the angular separation (as viewed from Earth) of the primary Centauri stars has been decreasing as they move through their orbits. It won’t be until December of this year that they’ll reach minimum separation as seen from Earth. We’ll need to give Alpha Centauri a little time, in other words, before we can hope to get data on other possible worlds around Centauri B.

Image (click to enlarge): Apparent and true orbits of Alpha Centauri. The A component is held stationary and the relative orbital motion of the B component is shown. The apparent orbit (thin ellipse) is the shape of the orbit as seen by an observer on Earth. The true orbit is the shape of the orbit viewed perpendicular to the plane of the orbital motion. According to the radial velocity vs. time [10] the radial separation of A and B along the line of sight had reached a maximum in 2007 with B being behind A. The orbit is divided here into 80 points, each step refers to a timestep of approx. 0.99888 years or 364.84 days. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

The Rajpaul paper is Rajpaul, Aigrain & Roberts, “Ghost in the time series: no planet for Alpha Cen B,” accepted for publication at Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (preprint). The Hatzes paper is “Radial Velocity Detection of Earth-Mass Planets in the Presence of Activity Noise: The Case of α Centauri Bb”, The Astrophysical Journal, Vol. 770, No. 2, (2013) (preprint).

SETI: No Signal Detected from KIC 8462852

I’ve mentioned before that I think the name ‘Tabby’s Star’ is a wonderful addition to the catalog. It trips off the tongue so much more easily than the tongue-twisting KIC 8462852, and of course it honors the person who brought this unusual object to our attention, Yale University postdoc Tabetha Boyajian. 1480 light years away, Tabby’s Star is an F3 with a difference. It produces light curves showing objects transiting across its face, some of them quite large, and the search is on to find an explanation that fits within the realm of natural causes.

Five articles about Tabby’s Star have already appeared in these pages, with the most likely explanation being some kind of cometary activity, an answer that seems to satisfy no one. We’ve also consulted both Boyajian’s paper on the subject and a paper by Jason Wright and colleagues out of the Glimpsing Heat from Alien Technologies project at Penn State. The light curves we’re looking at do fit the scenario of a ‘Dyson swarm,’ a cluster of power-collecting surfaces that an advanced civilization might create to extract maximum energy from its star.

Thus we can’t rule out the possibility of an extraterrestrial civilization, but no one is claiming that we’ve found one. The point is that in terms of Dysonian SETI, which looks for signs of another civilization’s activity in our astronomical data, Tabby’s Star is the most interesting target we’ve found, so it only makes sense to investigate it. Assuming we do deduce a natural cause for its signature, we will have learned something about an unusual astrophysical process, and that is all to the good. The sole driver here is to investigate and find out what is happening.

The SETI Institute has a natural interest in all this and has been deploying the Allen Telescope Array on Tabby’s Star for more than two weeks. Now we have an update on what the Institute has found. The effort used the Array’s 42 antennas north of San Francisco to look for narrow-band signals (approximately 1 Hz in width) that could be part of an interstellar beacon. In general, SETI at radio and optical frequencies (SETI, that is, of the non-Dysonian kind) looks for this kind of signal, a deliberate attempt by a civilization to declare its presence.

Image: Allen Telescope Array. Credit: Seth Shostak, SETI Institute.

But the SETI Institute also looked for broadband signals, an interesting choice. Here we are asking whether, if there really is an enormous astro-engineering effort going on around this star, there would be spacecraft sent out to service it. Our own investigations into quick travel around the Solar System point to microwave beaming as a feasible solution, the basis for an interplanetary infrastructure. Such intense microwave beams might well be visible, a kind of ‘leakage’ from the civilization’s activities that implies nothing about communication.

Here’s the result, from the SETI Institute’s paper on the work (Jy stands for jansky, a unit of density used in radio astronomy):

The observations presented here indicate no evidence for persistent technology-related signals in the microwave frequency range 1 – 10 GHz with threshold sensitivities of 180 – 300 Jy in a 1 Hz channel for signals with 0.01 – 100 Hz bandwidth, and 100 Jy in a 100 kHz channel from 0.1 – 100 MHz.

So no clear evidence for either kind of signal between 1 and 10 GHz. The paper goes on:

These limits correspond to isotropic radio transmitter powers of 4 – 7 1015 W and 1020 W for the narrowband and moderate band observations. These can be compared with Earth’s strongest transmitters, including the Arecibo Observatory’s planetary radar (2 1013 W EIRP [effective isotropically radiated power]). Clearly, the energy demands for a detectable signal from KIC 8462852 are far higher than this terrestrial example (largely as a consequence of the distance of this star).

What this initial search does is to place upper limits on anomalous emissions from Tabby’s Star. It tells us that we can rule out omnidirectional transmitters broadcasting narrow-band signals at approximately 100 times today’s total terrestrial energy usage, as well as broadband emissions of ten million times terrestrial energy usage. These numbers are high, as the Institute notes, but the paper goes on to say that required transmitter power for narrow-band signals could be reduced considerably if a signal were being beamed in our direction intentionally. It’s worth remembering, too, that any civilization of K2 status (capable of building a Dyson swarm) should have approximately 1027 watts to work with, the energy output of its star.

In any case, says Institute astronomer Seth Shostak, we keep looking:

“The history of astronomy tells us that every time we thought we had found a phenomenon due to the activities of extraterrestrials, we were wrong. But although it’s quite likely that this star’s strange behavior is due to nature, not aliens, it’s only prudent to check such things out.”

Exactly so. The authors add that the star will be the subject of observations for years to come.

Addendum: The Boquete Optical SETI Observatory in Panama is also going to be brought into the search, as per this story.

The paper is Harp et al., “Radio SETI Observations of the Anomalous Star KIC 8462852” (preprint). A SETI Institute news release is also available.

A 3D Look at GJ 1214b

An old friend used to chide me about the space program, asking good-naturedly enough why it mattered to travel nine years to get to a place like Pluto (this was not long after the New Horizons launch). ‘Just another rock,’ he would say. ‘Why go all that way to look at just another rock?’ Although we had many disagreements, Abe was one of the shrewdest people I’ve ever known. I had met him when he was in his sunset years, but in his prime he had run a large financial operation, been the subject of a story on the front page of the Wall Street Journal and had made a serious fortune in real estate speculation.

So what about this ‘just another rock’ meme? Abe died a few years back but I think about him in relation to things like yesterday’s story on Charon. The point is, it’s not just another rock. It’s this particular rock. And maybe it’s not a rock at all; maybe it’s a ball of icy slush. And maybe, as we’ve learned, it’s a seriously interesting thing that surpasses expectation. Each time we get to one of these places, or study a planet with transits and radial velocity methods, we’re seeing something never seen before. It may be able to teach us about conditions far different from those we experience and explain deep questions about the history of our own solar system.

Beyond that, each new ‘rock’ is part of a process of building understanding. We need to know what is around us because while we cannot solve all mysteries, we are compelled to solve the ones in front of us, the ones we can get to or develop the tools to investigate. The thing is, each time we go looking we seem to find something surprising, and then we need an answer for the conundrum. It’s a process that presumably began early in the development of our species.

I used to kid Abe by responding, ‘What does another dollar matter? It’s just another dollar.’ He got the point. Abe had a natural touch with money and knew how to make it multiply. Each new business venture was for him a kind of exploration. We just differed in the direction of our passions. I’ll take Charon or GJ 1214b over stock exchanges in New York or Tokyo, and that’s probably while you’ll never be reading about me on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.

An Exoplanet’s Clouds

So let’s talk about exoplanets. GJ 1214b is likewise ‘just another planet’ when viewed with the wrong filter. Viewed as we view things on Centauri Dreams, it’s one particular planet, and like so many we’ve found, it has its own set of things to teach us. Its star, an M-dwarf, is 42 light years away in the constellation Ophiuchus. Consider this planet a ‘mini-Neptune,’ one of the first discovered. What makes GJ 1214b so interesting is that it’s so close to our own system and gives us such a rich transit signature every 1.6 days.

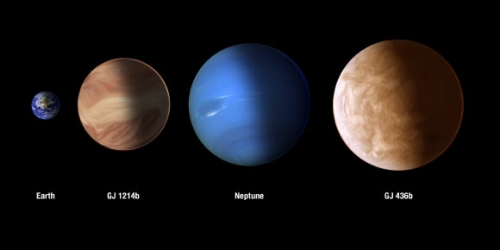

Image: Comparing the sizes of exoplanets GJ 436b and GJ 1214b with Earth and Neptune. Credit: NASA / ESA / A. Feild and G. Bacon, STScI.

We can use what is called transmission spectroscopy to study the atmospheres of places like this even though we can’t actually see the planet other than through its light curve. A planet passing in front of its star as seen from Earth offers us the opportunity to parse starlight that has been filtered through its atmosphere. The spectrum thus produced tells us about the composition of that atmosphere, its molecules and dust grains. It’s a method that has been used with great effect on worlds like HAT-P-11b and the ‘hot Jupiter’ HD 189733b.

The problem is, when we apply the techniques of transmission spectroscopy to GJ 1214b, nothing much happens. Studies using the Hubble instrument see little variation, a ‘flat spectrum’ that rules out an atmosphere of hydrogen, water, carbon dioxide or methane. Something in the planet’s atmosphere is evidently blocking out light. In a new paper, Benjamin Charnay (University of Washington), working with the university’s Victoria Meadows and several other researchers, has been attacking the problem, setting up models of varying atmospheric temperatures and composition that simulate a three-dimensional cloud structure.

Using a climate model developed by Charnay’s former research group in Paris, the scientist applied models previously used to study Titan to this intriguing exoplanet. GJ 1214b is close enough to its star that atmospheric temperatures are high, exceeding the boiling point of water. Clouds on a world like this would, Charnay believes, most likely be made of potassium chloride (KCl) or zinc sulfide (ZnS), lifted high into the atmosphere to produce such a flat spectrum. The model relies on a robust atmospheric circulation to boost these clouds to altitude.

But there is another potential source of GJ 1214b’s flat spectrum: A photochemical haze. Charnay is now looking at modeling hazes that could produce the same kind of spectrum. Data from the James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to be launched in 2018, will be needed to rule out alternatives. Assuming 0.5 µm particles (necessary to produce the flat spectra observed), the paper finds that potassium chloride clouds produce a constant reflectivity at visible wavelengths, while zinc sulfide clouds do not absorb at 0.5 µm, producing a peak of reflectivity. Organic haze, on the other hand, strongly absorbs at short visible wavelengths.

A stratospheric thermal inversion should show up at infrared wavelengths. From the paper:

The observation of a few primary/secondary eclipses or full orbits by JWST could provide very precise spectra and phase curves revealing GJ1214b’s atmospheric composition and providing clues on the size and optical properties (i.e. absorbing or not) of clouds. Non-absorbing clouds would suggest KCl particles. Absorbing clouds would favor ZnS particles or organic haze. In that case, the best way for determining the composition of cloud particles would be direct imaging or secondary eclipses/phase curves of reflected light in the visible. The different clouds/haze have characteristic features in visible reflectivity spectra. Future large telescopes such as ELT may have the capabilities for measuring this.

Charnay’s model shows how potassium chloride or zinc sulfide clouds would be created and lifted into the upper atmosphere, while also predicting the effect the clouds would have on planetary weather. The atmospheric circulation in this model is strong enough to carry KCl particles to high altitude regions while producing a minimum of cloud cover at the equator.

Just another rock? Look what we’re doing here: We’re studying layers of atmosphere on a planet we cannot see by using the spectroscopic signatures produced by a star 42 light years from the Sun. In astronomical terms, of course, that’s close, and GJ 1214b’s proximity makes it ideal for the study of mini-Neptunes. Moreover, it may be useful for understanding how our own planet’s atmosphere has changed over time, as Charnay notes in this UW news release:

“Worlds like Titan and this exoplanet have complex atmospheric chemistry that might be closer to what early Earth’s atmosphere was like. We can learn a lot about how planetary atmospheres like ours form by looking at them.”

The trick is in knowing what to look for and developing the tools to investigate — later resources, both space- and ground-based, will then be brought to bear to further the analysis. Given the wild multiplicity of exoplanets, we’re sure to be applying lessons learned at GJ 1214b to other mini-Neptunes, and generalizing from there to broader models of atmospheric evolution. Uncovering things, learning, pushing deeper is a compulsive process. We all have our obsessions, but I can’t think of a better one than the drive to explain other worlds.

The paper is Charnay et al., “3D modeling of GJ1214b’s atmosphere: formation of inhomogeneous high clouds and observational implications,” Astrophysical Journal Letters, Volume 813, Number 1 (abstract / preprint).

Unusual Crater on Charon

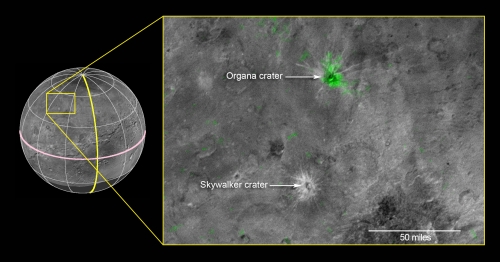

Another surprise from New Horizons, in a year which will surely see a few more before it ends. After all, we have a long flow of data ahead as the spacecraft continues to return the information it gathered during the July flyby of Pluto/Charon. Now we focus on Charon and the crater being called Organa, which produced an anomaly when scientists studied the highest resolution infrared compositional scan of the moon available. This crater and some of the surrounding materials show infrared absorption at about 2.2 microns, indicating frozen ammonia.

Not far away on Charon’s Pluto-facing hemisphere is Skywalker crater, which under infrared scrutiny shows the same composition as the rest of Charon’s surface. Here water ice — not ammonia — dominates. As this JHU/APL news release notes, ammonia absorption was first detected on Charon as far back as 2000, but what we’re seeing here is unusually concentrated. In any case, why is Organa so different from Skywalker and the rest of Charon’s craters?

Image: This composite image is based on observations from the New Horizons Ralph/LEISA instrument made at 10:25 UT (6:25 a.m. EDT) on July 14, 2015, when New Horizons was 81,000 kilometers from Charon. The spatial resolution is 5 kilometers per pixel. The LEISA data were downlinked Oct. 1-4, 2015, and processed into a map of Charon’s 2.2 micron ammonia-ice absorption band. Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) panchromatic images used as the background in this composite were taken about 8:33 UT (4:33 a.m. EDT) July 14 at a resolution of 0.9 kilometers per pixel and downlinked Oct. 5-6. The ammonia absorption map from LEISA is shown in green on the LORRI image. The region covered by the yellow box is 280 kilometers across. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

Organa and Skywalker are roughly the same size, about 5 kilometers in diameter, and both show the same ‘rays’ of ejected material, although Organa’s central areas are darker. But there seems to be no correlation: The ammonia-rich material extends beyond the dark area. One possibility is that the impactor that created Organa was rich in ammonia. An alternative posited by Will Grundy (New Horizons Composition team lead, Lowell Observatory) is that the crater could have been the result of an impact into a pocket of ammonia-rich subsurface ice.

“This is a fantastic discovery,” says Bill McKinnon (Washington University, St. Louis), deputy lead for the mission’s Geology, Geophysics and Imaging team. “Concentrated ammonia is a powerful antifreeze on icy worlds, and if the ammonia really is from Charon’s interior, it could help explain the formation of Charon’s surface by cryovolcanism, via the eruption of cold, ammonia-water magmas.”

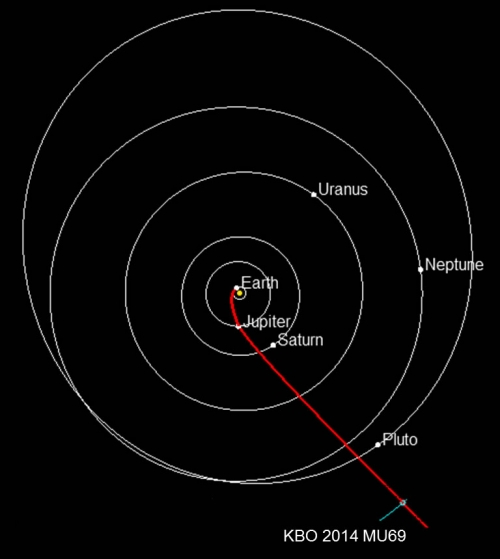

Meanwhile, New Horizons has now completed the third of its four trajectory-adjusting maneuvers needed for intercept of Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69. This was a 30-minute burn with the craft’s hydrazine thrusters and all indications are that it was successful. The fourth and final targeting maneuver is scheduled for today (November 4), although adjustments will be made later in the mission as more information about the KBO’s orbit is obtained. Remember that we only found 2014 MU69 in 2014, after a long search for a Kuiper Belt candidate.

Image: Projected route of NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft toward 2014 MU69, which orbits in the Kuiper Belt about 1.6 billion kilometers beyond Pluto. Planets are shown in their positions on Jan. 1, 2019, when New Horizons is projected to reach the small Kuiper Belt object. NASA must approve an extended mission for New Horizons to study the ancient KBO. Credit: JHU/APL.

Exoplanetology Beyond Kepler

Useful synergies continue to emerge among our instruments as we ponder the future of exoplanet studies. Consider the European Space Agency’s PLATO mission (PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars). Operating from the L2 Lagrangian point, PLATO will use 34 telescopes and cameras on a field of view that includes a million stars, using transit photometry, as Kepler did, to find planetary signatures. Working at optical wavelengths, PLATO will look for nearby Earth-sized and ‘super-Earth’ planets in the habitable zone of their stars.

This mission is scheduled to be launched in 2024, an interesting date because it’s also the year that the European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT) is scheduled to see first light. Huge new installations like these, although ground-based, are so powerful that they should be able, with the help of adaptive optics, to study planetary atmospheres on the PLATO-discovered planets. Thus we get the best of both worlds, with repairable and upgradable ground telescopes fleshing out the data gathered by our space instruments, just as today we can use Kepler data to find planet candidates and then confirm them using radial velocity studies from the ground.

The TESS mission (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) launches earlier (probably in 2018) but offers the same kind of synergies with other instruments. Both TESS and PLATO, for example, will hand off data to the James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled for a 2018 launch. Here again we can look for deepened studies of the targets other missions have found. And in the process, we can be assured that we’ll enrichen our catalog of extrasolar worlds.

Just what we might find is the subject of new work by Michael Hippke (Institute for Data Analysis, Neukirchen-Vluyn, Germany) and Daniel Angerhausen, a postdoc at NASA GSFC. Writing in The Astrophysical Journal, the duo explain in one recent paper that while planets with sizes and orbits similar to Mars or Mercury will be out of reach (around solar-class stars, at any rate), planets the size of Venus or Earth should show up readily for TESS and PLATO. The optimum target for life-hunters, of course, is an Earth-class world in an Earth-like orbit, and both instruments are believed to be capable of finding these. From the paper:

In this work, we have shown that future photometry will be able to detect Earth- and Venus-analogues when transiting G-dwarfs like our Sun… Larger sized planets (> 2R?) will be detected in a single transit around G-dwarfs, in low stellar noise cases, and assuming one can find them in the first place. The search techniques for such single transits will require further research and validation, and will likely be performed remotely, due to the large storage requirements.

But Hippke and Angerhausen’s interests extend beyond planets. They believe that a large planet like Jupiter that has several large moons should produce a characteristic signature, allowing its ‘exomoons’ to be detected. The detection would be marginal, as Angerhausen explains: “We wouldn’t have a clear detection, and we wouldn’t be able to say whether the planet had a single large moon or a set of small ones, but the observation would provide a strong moon candidate for follow-up by other future facilities.”

Let me drop back quickly to one of Hippke’s papers from early 2015, which explored exomoon candidates from the Kepler data, using what is known as the orbital sampling effect, which stacks numerous planet transits and tries to extract an exomoon signature. In this paper, Hippke used numerical simulations to inject exomoon signals into real Kepler data. This is useful because it shows us that there is a size limit to what we can find, one that TESS and PLATO should be able to improve on. The paper finds that for suitable planets with orbits between 35 and 80 days, an exomoon’s detectable radius is approximately 2120 kilometers, or about a third the radius of Earth, while for longer period planets, even larger moons are the minimum.

Such moons go beyond what we generally see in our system, but as the paper notes:

…our solar system might not be the norm – we have no Hot Jupiters, warm Neptunes, or Super-Earths in our solar system, and thus no reference for typical moons around such planets. Also, there is a strong selection bias, based on the detection limits…, and in addition the simple fact that the strongest dips are most significant. The first moons to be found will likely be at the long (large/massive) end of exomoon distribution, as was the case for exoplanets.

Hippke is surely right that the first moons found will be at the larger end of the size range, just as the first exoplanets we detected were massive worlds in close orbits that were the easiest to see with our instruments. For more on Hippke’s work and the methods he employs, see the article he wrote for Centauri Dreams, Exomoons: A Data Search for the Orbital Sampling Effect and the Scatter Peak.

But back to the Hippke and Angerhausen paper I started with. It notes that while the detection of moons will remain problematic for planets analogous to those in our own system, moons around planets orbiting quiet M-dwarf stars should be easier to detect. This paper, “Photometry’s bright future: Detecting Solar System analogues with future space telescopes,” focuses in directly on the capabilities of instruments like TESS and PLATO in offering datasets beyond Kepler’s.

Here again the authors deploy the Orbital Sampling Effect:

The OSE can be used to detect a significant flux loss before and after the actual transit (if present), which might be indicative of an exomoon in transit. The basic idea is that at any given transit the moon(s) must be somewhere: They might transit before the planet, after the planet, or not at all – depending on the orbit configuration. But by stacking many such transits, one gets, on average, a flux loss before and a flux loss after the exoplanet transit.

And bear in mind that moons are only one of the things we might expect to extract from TESS and PLATO data. Right now we have one detected ring system, around the planet J1407b, a massive ring more than 200 times larger than Saturn’s. The authors show that a transiting planet with a ring system produces a definitive signal. Even Trojan asteroids, which lead and follow a planet by 60 degrees in its orbit, should be in range for detection. In a third paper, the authors use Kepler data, injecting synthetic Trojan light curves to search for the limits of detectability. From the paper:

Our result gives an upper limit to the average Trojan transiting area (per planet) corresponding to one body of radius < 460km at 2? confidence. We find a significant Trojan-like signal in a sub-sample for planets with more (or larger) Trojans for periods >60 days.

The authors call these results tentative and suggest that improved data from TESS and PLATO should help us refine them. “As good as the Kepler data are, we’re really pushing them to the limit, so this is a very preliminary result,” adds Hippke in this NASA news release. “We’ve shown somewhat cautiously that it’s possible to detect Trojan asteroids, but we’ll have to wait for better data from TESS, PLATO and other missions to really nail that down.”

All of which tells us that we have much to expect from TESS and PLATO and the instruments that will subsequently home in on the targets they have provided. The papers are Hippke, “On the detection of Exomoons: A search in Kepler data for the orbital sampling effect and the scatter peak,” The Astrophysical Journal Vol. 806, No. 1 (abstract / preprint); Hippke and Angerhausen, “Photometry’s bright future: Detecting Solar System analogues with future space telescopes,” accepted at The Astrophysical Journal (preprint); and Hippke and Angerhausen, “A statistical search for a population of Exo-Trojans in the Kepler dataset,” accepted at The Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

Voyager Update: Probing the Boundary

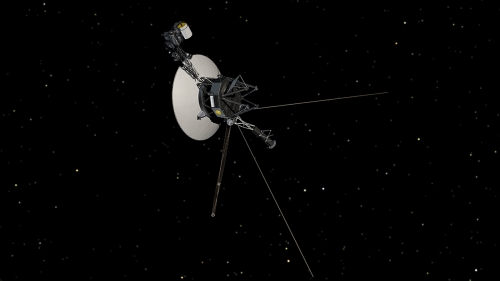

I always feel that my day starts right when a story involving the Voyagers crosses my desk. The scope, the sheer audacity of these missions in their day cheers me up, and the fact that they are still communicating with us is a continual cause for celebration. With Voyager 1 now moving beyond the heliosphere, we’ve got an interstellar craft on our hands, one that’s telling us a good deal about the perturbed regions through which it moves. Every day that the Voyagers stay alive is a triumph for an inquisitive and exploring species, and one day we’ll be launching their successor, targeting the local interstellar medium with instruments designed for the task.

Image: This artist’s concept shows NASA’s Voyager spacecraft against a backdrop of stars. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

The heliosphere is that ‘bubble’ blown by the particles of the Sun’s solar wind in surrounding interstellar space. As such, it’s a moving and malleable thing, flexing, flowing, contracting here, expanding there according to the stream of particles filling it from our star. Now we’re finding, not surprisingly, I think, that the magnetic field just outside the heliosphere is perturbed. Voyager 1 data show that the magnetic field here is more than forty degrees at variance from observations of the interstellar magnetic field that have been produced by other spacecraft.

Remember that while Voyager 1 is the first spacecraft to reach such distances from the Sun, we’ve had other missions exploring the outer regions of the system even though they operate well within it. The Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) is the outstanding example. Launched in 2009, IBEX is in Earth orbit (apogee 322,000 kilometers, perigee 16,000 kilometers), using instruments that track the solar wind’s interactions with ionized interstellar material. Like the Ulysses spacecraft before it, IBEX is also measuring inflowing neutral particles that penetrate the heliosphere, in the process creating a map of the Solar System’s elastic boundaries.

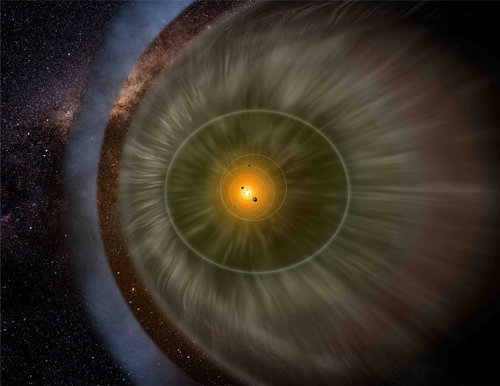

Image: An artist’s rendition of a portion of our heliosphere, with the solar wind streaming out past the planets and forming a boundary as it interacts with the material between the stars. Credit: Adler Planetarium/IBEX team.

IBEX has already told us a lot, including the fact that our Sun is located in a region of space where dust and gas are much more dispersed than they were when the Sun was formed. With IBEX data, scientists can map the distribution of elements like hydrogen, helium, neon and oxygen as they enter the heliosphere, and can use the neon to oxygen ratio in the Sun to trace element ratios in the distant past. We see less oxygen than expected in the interstellar medium today, indicating the changes to the medium since solar formation.

We also see that our Sun is close to the boundary of a local cloud of gas and dust, but still within it — this work challenges earlier Ulysses findings that found the Sun to exist between two clouds, though close to the boundary of the ‘Local Cloud.’ Within a few thousand years, we will be moving out of the Local Cloud and into a somewhat different galactic environment.

IBEX, then, is helping us understand the general region of space through which we move, while Voyager 1 is reporting on conditions just outside the heliosphere boundary. In 2009, IBEX data showed what principal investigator David McComas (SwRI) called a ‘very narrow ribbon that is two to three times brighter than anything else in the sky’ at the interstellar boundary. While this circular arc is still under study, the current view is that it is produced by neutral hydrogen atoms from the solar wind that were reionized in interstellar space and then became neutral again by picking up an additional electron. (For more on IBEX, see IBEX: The Heliosphere in Motion).

This is where the recent Voyager findings come in. Nathan Schwadron (University of New Hampshire) and colleagues have reanalyzed magnetic field data from Voyager 1, discovering that the direction of the magnetic field has been turning ever since the craft crossed into interstellar space. The work, published in Astrophysical Journal Letters confirms that the magnetic field direction at the center of the IBEX ‘ribbon’ is aligned with the magnetic field in the interstellar medium. Voyager is, in other words, now moving through a distorted region. By 2025, the magnetic field around it should align with the field direction found by IBEX.

At that point, we’ll be able to say that Voyager 1 has reached a more settled part of the interstellar medium, less perturbed by the ‘churn’ of the heliosphere. “This study provides very strong evidence that Voyager 1 is in a region where the magnetic field is being deflected by the solar wind,” says Schwadron in this JPL news release. A Voyager follow-up mission will be built from the outset as an interstellar probe, carrying instruments optimized for exploring this active boundary. We can hope that one day even more ambitious missions will use the data thus gathered to chart the regions through which they’ll fly on their way to another star.

The paper is Schwadron et al., “Triangulation of the Interstellar Magnetic Field,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 813, No. 1, L20. (abstract).