Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Habitable Worlds on Circumbinary Orbits?

Before I get into some NASA-funded exoplanet work that grew out of a study of the binary nature of Pluto and Charon, I want to mention that NASA TV will air an event of exoplanet interest on Tuesday the 7th, from 1700 to 1800 UTC. A panel of experts will be discussing the search for water and habitable planets, presenting recent discoveries of water and organics in our own system and relating them to the search for Earth-like worlds around other stars. NASA streaming video, along with schedules and other information, can be found here.

As to that Pluto/Charon work, it actually took Ben Bromley (University of Utah) and Scott Kenyon (Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory) much deeper into space when they began relating it to the formation of planets in circumbinary orbits around binary stars. These are planets that orbit both stars rather than one of the two. In other words, the work, funded by NASA’s Outer Planets Program, has examined the familiar ‘Tatooine’ scenario from Star Wars, where a sunset view may consist of two stars approaching the horizon simultaneously, a scenario that for a long time was deemed impossible.

Bromley and Kenyon’s mathematical models show that binary stars orbited by planetesimals can produce Earth-class planets close enough to the stars to be in the habitable zone as long as they are in concentric, oval-shaped rather than circular orbits. Such orbits change our perspective about what can happen around binary stars. Says Bromley

“…planets, when they are small, will naturally seek these oval orbits and never start off on circular ones. … If the planetesimals are in an oval-shaped orbit instead of a circle, their orbits can be nested and they won’t bash into each other. They can find orbits where planets can form.”

And he adds:

“We are saying you can set the stage to make these things. It is just as easy to make an Earthlike planet around a binary star as it is around a single star like our sun. So we think that Tatooines may be common in the universe.”

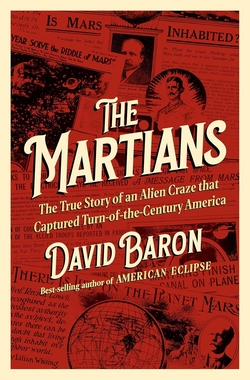

Image: In this acrylic painting, University of Utah astrophysicist Ben Bromley envisions the view of a double sunset from an uninhabited Earthlike planet orbiting a pair of binary stars. In a new study, Bromley and Scott Kenyon of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory performed mathematical analysis and simulations showing that it is possible for a rocky planet to form around binary stars, like Luke Skywalker’s home planet Tatooine in the ‘Star Wars’ films. So far, NASA’s Kepler space telescope has found only gas-giant planets like Saturn or Neptune orbiting binary stars. Credit: Ben Bromley, University of Utah

The conclusion is hardly intuitive, for two stars hosting an infant planetary system in this configuration perturb the region around them. It has been assumed that their gravitational interactions will clear out orbits to distances between 2 and 5 times the binary separation, with random motions among the planetesimals becoming high and destructive collisions frequent. More gentle merges and nudges are thought to be necessary for the formation of planets.

We do have seven circumbinary planets in inner orbits that have been identified by the Kepler telescope, but all are gas giants of Neptune-size or larger. Prevailing theories have suggested that such planets — the first discovered was Kepler-16b, a Saturn-mass planet at an orbital distance of 0.7 AU orbiting a K-class star and an M-dwarf — formed much further out in their systems and migrated closer to the stars because of gravitational interactions with another planet or the disk of gas surrounding the binary pair.

That conclusion may still hold for the gas giants so far detected, but the paper looks at all the Kepler circumbinary planets in light of the authors’ modeling and argues that there are other solutions beyond migration, particularly for smaller worlds. From the paper:

Toward understanding how circumbinary planets form, we re-examine a fundamental issue, the nature of planetesimal orbits around binary stars… [W]e describe a family of nested, stable circumbinary orbits that have minimal radial excursions and never intersect. While they are not exactly circular, these orbits play the same role as circular paths in a Keplerian potential. Gas and particles can damp to these orbits as they dynamically cool, avoiding the destructive secular excitations reported in previous work. Thus planetesimals may grow in situ to full-fledged planets.

These stable, non-Keplerian orbits, which the authors call ‘most circular,’ do not cross. Objects in such orbits respond to the mass of the central binary but also ‘experience forced motion, driven by the binary’s time-varying potential.’ It is this perturbation that keeps the planet from maintaining a circular orbit. A ‘most circular’ orbit is defined here as ‘having the smallest radial excursion about some guiding center, orbiting at some constant radius Rg and angular speed ?g in the plane of the binary.’

The result is that orbits inside a critical distance, pegged at twice the separation of the binary stars, are unstable, but beyond this distance, planet formation appears possible. After presenting their mathematical analysis, the authors go on to look at the Kepler circumbinary planets, finding that while in situ formation can produce rocky planets at the observed distances, this is unlikely to have occurred for the gas giants found by Kepler.

Most of the Kepler circumbinary planets seem to implicate migration of mass into the region where these objects are observed. Without larger samples of planets, it is impossible to distinguish between models where migration precedes assembly from those where migration follows assembly. All of the planets are too massive to allow in situ formation with no migration. However, the high free eccentricity observed in Kepler-34b and Kepler-413b are consistent with scattering events. Improved constraints on the orbits and bulk properties (mass, composition, spin, etc.) might allow more rigorous conclusions on their origin.

The argument here is not that migration cannot be a viable way to move planets into inner circumbinary orbits, but that both migration and in situ formation are possible. Outside of the critical region near the binary, planet formation can happen the same way it does around a single star, with planetesimal orbits allowing mergers, fragmentation and stirring of the material that will grow into stable worlds over time. In our own Solar System, the small moons of the Pluto/Charon binary may have formed in the same way.

We may not be seeing small, rocky worlds in inner circumbinary orbits that formed in situ because they are so much smaller than the gas giants thus far detected, but if the oval ‘most circular’ orbits the authors describe are indeed possible, we should start finding them. Migrating gas giants explain our current detections, in other words, but habitable rocky worlds in such systems should be able to form and remain stable in their original orbits.

The paper is Bromley and Kenyon, “Planet formation around binary stars: Tatooine made easy,” submitted to The Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

Fast Radio Bursts: SETI Implications?

With SETI on my mind after last week’s series on Dysonian methods, it seems a good time to discuss Fast Radio Bursts, which have become prominent this week following the appearance of a new paper. A New Scientist piece titled Is this ET? Mystery of strange radio bursts from space is also circulating, pointing out that these powerful bursts of radio waves lasting for milliseconds, each covering a broad range of radio frequencies, are still unexplained, and that they seem to follow a mathematical pattern.

Image: The 64-metre Parkes radio telescope in New South Wales (Australia), where Fast Radio Bursts of unknown origin have been detected. Credit: CSIRO Parkes Observatory.

Eleven bursts have been detected so far, dating back to 2001. The paper, by Michael Hippke (Institute for Data Analysis, Neukirchen-Vluyn, Germany), Wilfried Domainko (Max-Planck-Institut fur Kernphysik, Heidelberg) and John Learned (University of Hawaii, Manoa), points out that the pulses have dispersion measures higher than we would expect from sources inside the galaxy. But for reasons the paper goes on to explain, they’re probably not of extragalactic origin.

To untangle all this, let’s pause on the term ‘dispersion measure.’ It comes from the study of radio pulsars, where it has been observed that a pulse can be delayed depending upon its radio frequency as it sweeps through charged particles.

To clarify this, let me quote from a useful online discussion on pulsar research that Ryan Lynch (now at McGill University) published on the matter. Lynch points out that the dispersion measure (DM), which is a characteristic of a pulsar signature, doesn’t have anything to do with the pulsar itself. It is, instead, a marker that tells us something about the space between Earth and the pulsar, or as in the case above, a Fast Radio Burst. That space may contain various charged particles, but the delay they produce is inversely proportional to the mass of the particles — in other words, the amount of dispersion is dominated by electrons. According to Lynch:

These electrons disperse the pulsar’s signal… causing lower observing frequencies to arrive later than higher observing frequencies. The electrons can also scatter the signal much the same way smoke scatters visible light. The dispersion measure is a way of telling us how many electrons the signal encountered on its way to Earth. The larger the dispersion measure, the more electrons the signal encountered. This could happen for two reasons — either the pulsar is very far away, or the density of electrons in the space between Earth and the pulsar is relatively high. Both will cause an increase in the dispersion measure.

Michael Hippke and team want to consider what the dispersion measures of the detected Fast Radio Bursts tell us about their nature, hence the title of the paper, “Discrete Steps in Dispersion Measures of Fast Radio Bursts.” It’s an interesting astronomical question because it could be that FRBs could be used as ‘standard candles’ that could help us understand more about dark energy. The researchers wanted to know whether a clustering in the dispersion measure values could show which came from within our galaxy and which from without.

What turns up is what the authors describe as a ‘potential discrete spacing in DM of the FRBs.’ The bursts’ dispersion measures are integer multiples of the number 187.5, which the paper argues makes an extragalactic origin unlikely. The thinking here is that intergalactic dust would randomize the DM values, and thus we are more likely dealing with a source within the Milky Way. Just what the source could be makes for interesting speculation. From the paper:

A more likely option could be a galactic source producing quantized chirped signals, but this seems most surprising. If both of these options could be excluded, only an artificial source (human or non-human) must be considered, particularly since most bursts have been observed in only one location (Parkes radio telescope). A re-assessment of man-made phenomena, such as perytons (Burke-Spolaor et al. 2011), would then be required. Failing some observational bias, the suggestive correlation with terrestrial time standards seems to nearly clinch the case for human association of these peculiar phenomena.

That latter point has to do with the fact that FRBs seem to arrive at close to the full integer second, suggesting a man-made signal. As to the Burke-Spolaor paper cited above, it examines a series of pulses likewise detected at the Parkes instrument that are, as the abstract says, of ‘clearly terrestrial origin,’ and hence an example of our need to tune up radio-pulse survey techniques to rule out terrestrial signals. I also note the citation’s last sentence, which makes the case for a human origin. But as the Hippke paper points out, ‘In the end we only claim interesting features which further data will verify or refute.’

FRBs merit our attention because while we may have a human origin for these bursts, it’s conceivable that an extraterrestrial beacon could be in play. New Scientist quotes Jill Tarter, former director of the SETI Institute, as saying “I’m intrigued. Stay tuned.” Which we’ll all do, though mindful of the fact that with such a small number of bursts, we are working with little data. A hitherto undiscovered astronomical phenomenon would be a useful discovery, but we need to see how the pattern holds up as more FRBs are detected.

Back in 1967, The Byrds produced a song called “CTA-102,” a musical reflection of the discussion of the quasar by the same name, whose emissions had excited worldwide interest. Nikolai Kardashev himself wondered in 1963 whether a Type II or Type III civilization could be behind the then unidentified source, and subsequent observations by Gennady Sholomitskii kept the idea in the public imagination. We found a natural explanation for CTA-102, but as with FRBs, checking our data against the possibility of extraterrestrial communication makes good sense and could in the process reveal a new type of astronomical object or, more likely, a nearby human explanation.

The paper is Hippke et al., “Discrete Steps in Dispersion Measures of Fast Radio Bursts” (abstract). The Burke-Spolaor paper is “Radio Bursts with Extragalactic Spectral Characteristics Show Terrestrial Origins,” Astrophysical Journal Vol. 727, No. 1 (2011), 18 (abstract).

A Fresh Look at Rhea

When it comes to Saturn, have you noticed what’s been missing lately? Well, actually for the last two years. While the Cassini orbiter has had high-profile encounters with Titan, it has been in a high-inclination orbit that has meant no recent flybys of other Saturnian moons. All that has now changed as Cassini returned to the planet’s equatorial plane this month, which means we can look forward to more interesting views like these mosaics of the planet’s second largest moon Rhea.

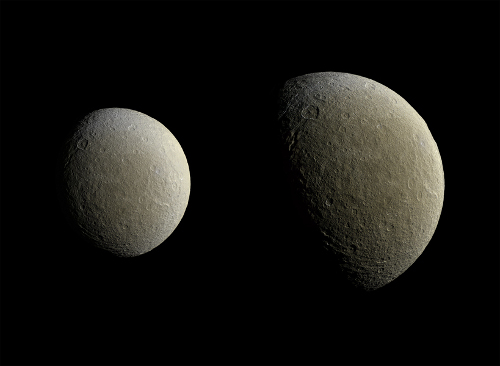

Image: Two mosaics of Saturn’s icy moon Rhea, with constituent images taken about an hour and a half apart on February 9, 2015. Images taken using clear, green, infrared and ultraviolet spectral filters were combined to create these enhanced color views, which offer an expanded range of the colors visible to human eyes in order to highlight subtle color differences across Rhea’s surface. The moon’s surface is fairly uniform in natural color. Credit: JPL.

The Rhea imagery comes from a flyby of the moon on February 9, the first encounter other than Titan since early 2013. Resolution in the smaller mosaic is 450 meters per pixel, while the view on the right has a resolution of 300 meters per pixel. The images going into the mosaic on the right were acquired at a distance that ranged from 57,900 kilometers to 51,700 kilometers; those on the left from distances between 82,100 to 74,600 kilometers. Each mosaic is made up of multiple narrow-angle camera (NAC) images, with wide-angle camera data used where necessary to fill in the areas where the NAC data were not available.

Rhea is the ninth largest moon in the Solar System, and while it doesn’t turn up very often in discussions of astrobiology, I should note a 2006 paper from Hauke Hussmann (Universidade de São Paulo) and colleagues that investigates the possibility of sub-surface oceans in the medium-sized icy satellites as well as the largest trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). The paper argues that assuming differentiation and an equilibrium between heat production in the rocky cores and heat loss through the ice shell, sub-surface oceans are possible on Rhea, Titania, Oberon, Triton, and Pluto and on the large TNO’s Eris, Sedna, and Orcus (2004 DW).

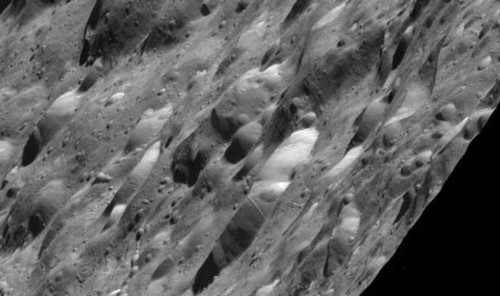

Image: Cassini’s wide-angle camera took this image of Rhea from about 200 kilometers away from the moon’s surface in early 2011. Credit: JPL.

Back in 2011, Cassini completed a close flyby of Rhea, with closest approach achieved on January 11 of that year. The imagery above shows an old, cratered and apparently inert surface, with some evidence of straight faults that show up better in other Rhea imagery. Further study of Rhea via Cassini will help us determine how its extremely tenuous atmosphere of oxygen and CO2 interacts with particles in Saturn’s magnetosphere.

Next up for Cassini in its new, nearly equatorial orbit: A May 7 flyby of Titan, the first of four in 2015, as well as two encounters with Dione and three with the always interesting Enceladus. The Hussmann paper mentioned above is “Subsurface oceans and deep interiors of medium-sized outer planet satellites and large trans-neptunian objects,” Icarus Volume 185, Issue 1 (November 2006), pp. 258-273 (abstract).

An Alpha Centauri Bb Transit Search

Alpha Centauri continues to be a maddening and elusive subject for study. Two decades of radial velocity work on Centauri A and B have been able to constrain the possibilities — we’ve learned that there are no gas giants larger than Jupiter in orbits within 2 AU of either of the stars. But lower mass planets remain a possibility, and in 2012 we had the announcement of a planet slightly more massive than Earth in a tight orbit around Centauri B. It was an occasion for celebration (see Lee Billings’ essay Alpha Centauri and the New Astronomy for a glimpse of how that moment felt and how it fit into the larger world of exoplanet research).

But the candidate world, Centauri Bb, remains controversial, and for good reason. The work involved radial velocity methods at a level of precision that pushed our instruments to the limit. Andrew LePage explored the issues in Happy Anniversary α Centauri Bb?, where the question-mark tells the tale. Here he discusses the instrumentation involved in the 2012 work:

The first team to announce any results from their search was the European team using the HARPS (High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planetary Searcher) spectrometer on the 3.6-meter telescope at the European Southern Observatory in La Silla, Chile. They employed a new data processing technique to extract the 0.5 meter per second signal of α Centauri Bb out of 459 radial velocity measurements they obtained between February 2008 and July 2011. These radial velocity data had a measurement uncertainty of 0.8 meters per second and contained an estimated 1.5 meters per second of natural noise or “jitter” resulting from a range of activity on the surface of α Centauri B modulated by its 38-day period of rotation.

A planet with a 3.24 day orbital period was the result of an extremely low-amplitude signal, and subsequent analysis raised doubts about its validity, with Artie Hatzes (Thuringian State Observatory) finding that additional observations were needed to make sure we weren’t seeing noise in the data instead of a planet. Bear in mind that we also have Debra Fischer (Yale University) and team investigating Alpha Centauri Bb at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in Chile and a team at Mt. John University Observatory in New Zealand.

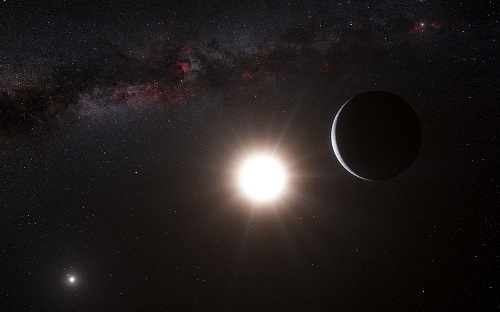

Image: An artist’s impression of the still unconfirmed α Centauri Bb, whose discovery was announced on October 16, 2012. The planet is the subject of a new transit search discussed below. (Credit: ESO/L. Calçada/Nick Risinger)

Now comes Brice-Oliver Demory (University of Cambridge), whose team has gone after a different kind of detection, working with the Hubble Space Telescope on a transit search of Centauri B in hopes of finding the signature of the controversial planet. Transits depend upon the alignment of star, planet and observer, so a null result doesn’t demonstrate that the planet doesn’t exist, but using 40 hours of observation, the team was able to rule out a transit of Centauri Bb under the published orbital parameters with a confidence level of 96.6 percent.

The story does have an intriguing coda in the form of a single 2013 event, one that lasted longer than expected for a Centauri Bb transit. The team worked through the possibilities of instrument error and other factors, as the paper explains:

We explore in the following the possibility that the July 2013 transit pattern is due to stellar variability, instrumental systematics or caused by a background eclipsing binary. We do not find any temperature or HST orbital dependent parameter, nor X/Y spectral drifts to correlate with the transit pattern. The transit candidate duration of 3.8 hours is 2.4 times longer than the HST orbital period, making the transit pattern unlikely to be attributable to HST instrumental systematics. As the detector is consistently saturated during all of our observations, we also find it unlikely that saturation is the origin of the transit signal.

Another source of confusion could be activity on the star itself, but the researchers do not see it as a factor:

…the duration of the transit candidate (3.8-hr) is not consistent with the stellar rotational period of 36.2 days…, to enable a spot (or group of spots) to come in and out of view. In such a case, star spots would change the overall observed flux level and produce transit-shape signals, as is the case for stars having fast rotational periods…

We are left with the possibility that this may have been an actual planetary transit with a different orbital period than described in the Centauri Bb discovery paper. Is it a second possible planet around Centauri B, one with an orbital period in the vicinity of 20 days? It will take follow-up photometric observations of an extremely tricky stellar system to tell us more.

In this New Scientist article on the Hubble observations, Demory mentions the possibility of a low-cost, perhaps crowd-funded mission, a small satellite whose sole purpose would be the kind of intensive Alpha Centauri ‘stare’ that busy instruments like Hubble haven’t time for. It’s an interesting idea, and would make for a KickStarter project in the range of $2 million. Says Demory: “Anyone fancy chipping in to find our nearest neighbours?”

The paper is Demory et al., “Hubble Space Telescope search for the transit of the Earth-mass exoplanet Alpha Centauri B b,” accepted at Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (preprint). For a thorough analysis of the data involved in this work, see Andrew LePage’s essay Has Another Planet Been Found Orbiting Alpha Centauri B?

SETI Explores the Near-Infrared

This has been a week devoted to extraterrestrial technologies and the hope that, if they exist, we can find them. Large constructions like Dyson spheres, and associated activities like asteroid mining on the scale an advanced civilization might use to make them, all factor into the mix, and as we’ve seen, so do starships imagined in a wide variety of propulsion systems and designs. Dysonian SETI, as it is called, takes us into the realm of the hugely speculative, but hopes through sifting our abundant astronomical data to find evidence of distant engineering.

This effort is visible in projects like the Glimpsing Heat from Alien Technologies (G-HAT) SETI program, which proceeds in the capable hands of Jason Wright and colleagues Steinn Sigurðsson and Matthew Povich at Penn State (see Wright’s Glimpsing Heat from Alien Technologies essay in these pages as well as his AstroWright blog). For those wanting to follow up these ideas, an excellent introduction is the paper “Dysonian Approach to SETI: A Fruitful Middle Ground?”, which ran in JBIS in 2011 (Vol. 64, pp. 156-165). It’s not, unfortunately, available online, though the British Interplanetary Society offers a print copy of the entire back issue here.

Image: NGC 2403 in Camelopardalis. Dysonian SETI, not limited to relatively nearby stars, looks for signs of astroengineering not just in our own but in distant galaxies like this one, some ten million light years away.. Credit & Copyright: Martin Pugh.

Into the Infrared

The more conventional radio and optical SETI methods continue as well. I’ve written often in these pages about Frank Drake’s Project Ozma at the Green Bank (WV) site, and cited the classic 1959 paper “Searching for Interstellar Communications” by Giuseppe Cocconi and Philip Morrison, which more or less opened up the entire field. But equally significant is Charles Townes’ 1961 paper “Interstellar and Interplanetary Communication by Optical Masers,” which ran in Nature (Vol. 190, No. 4772, pp. 205-208), from which this quote:

We propose to examine the possibility of broadcasting an optical beam from a planet associated with a star some few or some tens of light-years away at sufficient power-levels to establish communications with the Earth. There is some chance that such broadcasts from another society approximately as advanced as we are could be adequately detected by present telescopes and spectrographs, and appropriate techniques now available for detection will be discussed. Communication between planets within our own stellar system by beams from optical masers appears a fortiori quite practical.

Townes, who died recently, built the first maser, which worked primarily in the microwave region of the spectrum. He was a major figure in the development of both maser and laser technologies, and a winner of the Nobel Prize in 1964. The field of optical SETI has not been as visible as the older radio SETI but its proponents are actively pursuing the search at sites like Lick Observatory, where the 1-meter Nickel Telescope has been equipped with a new pulse-detection system using three light detectors, an installation that allows what Frank Drake calls “…perhaps the most sensitive optical SETI search yet undertaken.”

The new instrument is called NIROSETI, which stands for near-infrared optical SETI. It promises to gather copious data by recording levels of light over time to look for patterns that might signify a distant civilization. The beauty of working at near-infrared wavelengths is that such light penetrates much farther through gas and dust than visible light, helping us widen the search to stars thousands of light years away. NIROSETI saw first light on March 15.

Unlike Dysonian SETI, optical SETI operates under the premise that an extraterrestrial civilization may be trying to communicate with us, beaming light explicitly at our Solar System. According to this news release from the SETI Institute, NIROSETI’s use of three light detectors will allow the team to separate the brief pulses of light they are looking for from false alarms of the sort that have troubled other optical SETI experiments using fewer detectors. Optical SETI ‘noise’ can consist of cosmic rays, incident starlight, muon showers and radioactive decay in the glass of the photomultiplier tubes of the detectors, all events to be screened out of the data.

Dan Werthimer, who along with Richard Treffers (UC-Berkeley) designed an earlier instrument for optical SETI, notes where NIROSETI departs from its predecessors:

“This is the first time Earthlings have looked at the universe at infrared wavelengths with nanosecond time scales. The instrument could discover new astrophysical phenomena, or perhaps answer the question of whether we are alone.”

Shelley Wright (UC-San Diego) led the development of the new instrument while at the University of Toronto, finally signing off on detectors sensitive enough to deploy on the telescope. In addition to Wright and Werthimer, the group also includes Geoff Marcy and Andrew Siemion (UC-Berkeley), Patrick Dorval and Elliot Meyer (University of Toronto) and pioneering SETI scientist Frank Drake, whose take on the investigation is determinedly optimistic:

“There is only one downside: the extraterrestrials would need to be transmitting their signals in our direction. If we get a signal from someone who’s aiming for us, it could mean there’s altruism in the universe. I like that idea. If they want to be friendly, that’s who we will find.”

Image: Skies cleared for a successful first night for NIROSETI at Lick Observatory. The ghost image is Shelley Wright, pausing for a moment during this long exposure as the rest of her team continued to test the new instrument inside the dome. Credit: UC-San Diego.

We can hope that Frank Drake’s ideas come to pass. In any event, it’s clear that the definition of SETI is evolving as we continue to explore radio, optical and Dysonian strategies. In my view, the emergence of the Dysonian approach has been a genuine boon for our investigations. It reminds us how much astronomical data we have accumulated that can now be subjected to analysis in these terms. Will evidence of the existence of an extraterrestrial civilization come, if it does come, through a radio burst, an optical signal, or the observation of an anomaly in a distant galaxy?

Starship Detection: The K2 Perspective

‘Classical’ SETI, if I can use that term, is based on studying the electromagnetic spectrum primarily in the radio wavelengths thought most likely to be used for communication by an extraterrestrial civilization. SETI’s optical component is largely focused on searching for signals intended as communication. What is now being called Dysonian SETI is a different approach, one based on gathering observational evidence that may already be in our archives, data that demonstrate the existence of extraterrestrial activity far beyond our capability.

Just as a Dyson Sphere would reveal the workings of a civilization of Kardashev Type II — producing something like ten billion times the energy of a Type I culture — the detection of a starship would show us technology in action, even if the craft were, as Ulvi Yurtsever and Steven Wilkinson have speculated, a vehicle pushing up against light speed millions of light years away. As physicist Al Jackson has tackled starship detection in recent years, he has taken note of the work of D. R. J. Viewing and Robert Zubrin, which dealt with some but not all design and detection possibilities. Beamed propulsion, for example, does not turn up in these sources.

Jackson also points to a caveat in such work: If we are hoping to detect a starship using many of the methods described in previous studies, we need to be inside the engine’s exhaust cone or the transmitter cone of the energy beam. We also know that the cone will be narrow. Even so, there are a number of ways to proceed, ranging from the craft’s interactions with the interstellar medium to detection of its own waste heat.

Image: Physicist Al Jackson. I can’t remember who took this (it may even have been me).

Imagine a highly advanced ship built by a Kardashev Type II civilization. Give it a gamma factor of 500, which translates to 0.999998 times the speed of light. Assume the ship is as hot as 5000 K (near the melting temperature of graphene). All these are extreme assumptions (see below) but we’re pushing the envelope here. This is, after all, K2.

Would we be able to detect such a craft? Waste heat can be modeled as isotropic radiation, says Jackson, in the rest frame of the ship, while to an observer in another inertial frame, this radiation appears beamed. We get this result:

Considering a ship of modest size and mass, a K2 ship accelerating at one gravity. For instance, if we have a ship 1000 meters long and 50 meters in diameter, generating 11402 terawatts in its rest frame, Doppler boosting will generate approximately 1.2×108 terawatts beamed into the forward direction. However… unless the ship is headed straight at the observer, it will be hard to see. Take into account the Doppler shifting of the characteristic wavelength, from near green in the rest frame to soft x-ray in the observer’s frame. One might look for small anomalies in data from a host of new astrophysical satellite observatories.

Not very encouraging, but then, detecting the signature of a starship is not going to be easy. One possible place to look is in the realm of what Jackson calls ‘gravitational machines,’ such as the massive binaries Freeman Dyson once suggested could be used as gravitational slingshots. We might consider not just white dwarf and neutron star binaries but even black hole binaries. A gravitational assist in such scenarios might reach as high as .006c.

On the other hand, wouldn’t a civilization that could already reach binaries like these have acquired capabilities greater than those it would gain by using the binaries in the first place? Perhaps better to consider black holes as a source of direction change for fast-moving starships. Jackson points out that a starship orbiting a black hole will have visible waste radiation. In fact, a close-orbiting ship will have fluctuating emissions peaked at those times that the ship, black hole and observer line up, a phenomenon that is the result of gravitational focusing.

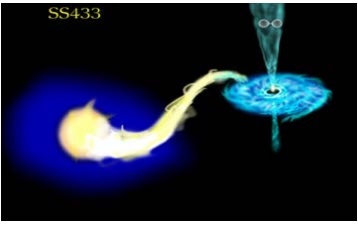

Other extreme astronomical objects may be worthy of investigation in these terms. Jackson points to SS 433, a neutron star or black hole orbited by a companion star, with material being drawn from the companion into an accretion disk. Jets of particles are being blown outward from the poles. While at SS 433 the particles in the jets are moving at 26 percent of the speed of light, jet material in configurations like these can reach 95 percent of lightspeed. Using such jets to propel magsails that reach .5 times the speed of light would allow a K2 civilization an abundant source of energy for repeated missions at a high percentage of c.

Image: Magsail ‘jet riding’. Credit: Doug Potter.

We don’t know what a K2 civilization will choose to do, but exploiting naturally occurring resources like these may be an attractive proposition. There may be interesting prospects not just for magsails but so-called ‘lightsails’ around extreme astronomical objects:

Consider a K2 civilization taking advantage of a Schwarzschild or Kerr black hole as a means of focusing radiation from a beaming station onto a sail. The advantage of this is the tremendous amount of amplification possible. One of the most promising modes of interstellar flight propulsion is the use of a sail, a transmitter, and maybe a ‘lens’ to focus a beam of laser light or microwaves. Extrapolate to a K2 civilization the use of a black hole as the focusing device. An approximate calculation for a Schwarzschild black hole shows that beamed radiation can be amplified by a factor 105 to 1015.

So-called ‘strong focusing’ is tricky to model and, as Jackson explains in some detail, the astronomical configuration — the location of a source and the best location for the sail — are topics that need much more work. But the idea that a K2 civilization would use the immense energies available in the area of black holes makes them a natural hunting ground for Dysonian SETI activity. Could a black hole in the vicinity of a starship’s destination be used for braking?

Robert Bussard’s 1960 paper on interstellar ramjets posited a spacecraft that could collect gas from the interstellar medium, compressing it to a plasma that could be brought to fusion temperatures. Carl Sagan would later suggest that a magnetic scoop would be the ideal way for this gas collection to proceed, but later work by Dana Andrews and Robert Zubrin revealed how much drag such a magnetic scoop would produce. The ‘magsail’ actually acts like a brake.

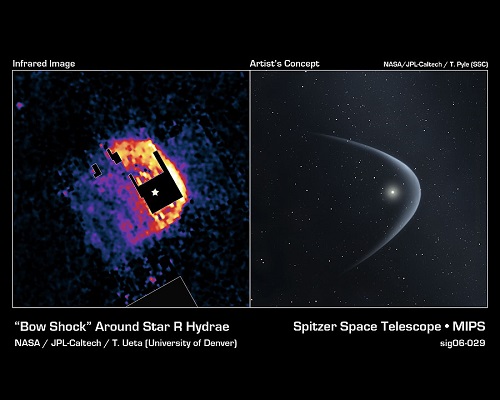

Why not, then, use these magsail properties, shedding energy and momentum as a spacecraft nears its destination? Craft moving at relativistic velocities might find this an efficient way to arrive, one that produces a ‘bow shock’ whose radiation ranges from the optical to the X-ray bands. “A starship will be much smaller than a neutron star,” writes Jackson, “but detection of the radiation signature of a starship’s bow shock could imply a very peculiar object.”

Image: Two examples of neutron star bow shock, the one on the right an artist’s concept. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Jackson’s paper is a work in progress, with an early version printed in Horizons, the AIAA bulletin for the organization’s Houston chapter. A journal submission is in the works as he refines the draft. It’s a fascinating discussion that reminds us how much we have to speculate about when we talk K2 civilizations. Jackson notes the major assumptions: Ships can run ‘hot,’ and that means as high as 5000 K; material structural strength limits have been overcome; extreme accelerations are allowable and dust/gas shielding issues resolved. We can argue about the limits here, but it’s clear that a K2 civilization will have capabilities far beyond our science, and it may be the random anomaly in astronomical data that flags its existence.