Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

We Have Fed Our Sea

One of the reasons I do what I do is that when I was a boy, I read Poul Anderson’s The Enemy Stars. Published as a novel in 1959, the work made its original appearance the previous year in John Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction as a two-part serial titled “We Have Fed Our Sea.” The reference is to Kipling’s poem “The Song of the Dead,” from which we read:

We have fed our sea for a thousand years

And she calls us, still unfed.

Though there’s never a wave of all her waves

But marks our English dead…

Space was, for Anderson, the new sea, one whose imperatives justify the sacrifices we make to conquer her, and “We Have Fed Our Sea” is a far better title for this work than its book version. Kipling writes:

We were dreamers, dreaming greatly, in the man-stifled town;

We yearned beyond the sky-line where the strange roads go down.

Came the Whisper, came the Vision, came the Power with the Need…

I bought The Enemy Stars at the Kroch’s and Brentano’s bookstore on S. Wabash Avenue in Chicago (this was the flagship store of the chain, and what an astonishing place it was for a book-dazzled boy like me to wander about in). I still have that paperback, and I can remember picking it up because of what was on the back cover:

They built a ship called the Southern Cross and launched her to Alpha Crucis. Centuries passed, civilisations rose and fell, the very races of mankind changed, and still the ship fell on her headlong journey toward the distant star. After ten generations the Southern Cross was the farthest thing from Earth of any human work – but she was still not halfway to her goal…

That was my first encounter with the idea that we might go to the stars in multi-generational ways. But Poul Anderson was always ahead of his time, and this is not a generation ship in the model of, say, Heinlein’s Orphans of the Sky. People do not live out their lives aboard the Southern Cross and hand on the great imperative of the mission to their descendants. Instead, crews in the Solar System are regularly teleported out to the ship.

It’s a wonderful story, and that Kipling reference will put a chill up your spine when you see what Anderson does with it. Baen Books incorporated a later novella called “The Ways Of Love” into its edition of The Enemy Stars in 1987, but I much prefer the unadorned core story. I went back to it this past weekend after writing On the Role of Humans in Starflight on Thursday, having thought for several days about the different ways we approach doing long-term things. Probably if I had read Nelson Bridwell’s just published essay To Be or Not to Be? Mankind’s Exodus to the Stars a day earlier, I would have incorporated it into the Thursday post.

But today will do just as well, for Bridwell’s themes are much to the point, reminding me of generation ships in all their manifestations, as well as generation-spanning projects. Described as a ‘senior machine vision engineer working in manufacturing automation,’ the author sees interstellar flight as a natural and necessary outcome of our space efforts, one that will take millennia and will not require violations of physical law. It is an effort, though, that should not be delayed. Writes Bridwell:

Because starships will not be ready to go for many centuries and interstellar voyages may last for thousands of years, we will want to get started sooner rather than later, initially allocating a small but steady fraction of the space budget to identify the most promising engineering approaches and performing early proof-of-concept experiments when affordable. The first application of this technology will be for unmanned interstellar probes that will conduct close-up reconnaissance of nearby solar systems.

Taken to its outer limit, a long-term perspective on Earthly life tells us that the planet will eventually meet its doom, if in no other way, through the gradual swelling of our parent star. But as Bridwell points out, we’re a long way from not just starflight but even a sustained human presence off this planet. It’s prudent, then, to do whatever we can to minimize the existential risk of something happening in the interim to destroy our species. That might involve accelerating the search for near-Earth asteroids and comets to provide plenty of time to change the trajectories of those in dangerous orbits. It also might involve a heightened awareness of and countermeasures for the kind of pandemic that could cut the population in half, if not worse.

In terms of space, bringing the long-term focus of interstellar thinking into play involves continuing the search for promising nearby solar systems where humans may eventually travel even as we develop the kind of closed-loop life support technologies that would sustain human crews over the duration of long voyages. The latter aspect receives far less attention than it should, but it is as key a driver as propulsion for figuring out how to make star journeys.

I think Bridwell has it right that an interstellar effort grows directly out of sustained development here in our own Solar System. We will learn the essentials of closed-loop life support by experimenting in places much closer to home than even the nearest star:

Because it is not at all likely that a warm, moist, green, oxygen-rich twin of Earth will be within our reach, the third goal must be learning how to live under less-ideal conditions, such as on the Moon. We should establish manned outposts on the Moon and Mars where we can develop the expertise to efficiently manufacture everything that we need from local planetary materials. Over the course of hundreds of years, as these outposts grow, they will become second homes within this solar system for humanity.

I see this in terms of O’Neill-class colonies that gradually grow in size and sophistication, as well as bases on planetary surfaces. The immediate need is to develop our skills at living in nearby space so that if something does happen to our planet — nuclear war, perhaps, or biological catastrophe — enough colonies will exist to perpetuate the species. Over the course of the next few centuries, creating such self-sustaining populations in space should be within our technological powers, and these will inevitably spread outward as we explore our system’s resources. I find this prospect encouraging because it assumes nothing the laws of physics do not allow.

Bridwell wonders whether our reluctance to think beyond the current moment is not itself a passing phenomenon, perhaps ‘a madness left over from the Cold War.’ I do think it is a cultural phenomenon, though I have no opinions about its origins in 20th Century geopolitics. We make our own values by choosing what to build, what to believe in, and what goals to pursue. A positive perspective is one that protects the home world first while ensuring that unexpected catastrophe cannot destroy our species. It then begins the long process of exploration and settlement that may spread as far as the outer planets, or perhaps the Oort Cloud, or if we have the determination to make it happen, the distant stars Poul Anderson saw as our destiny.

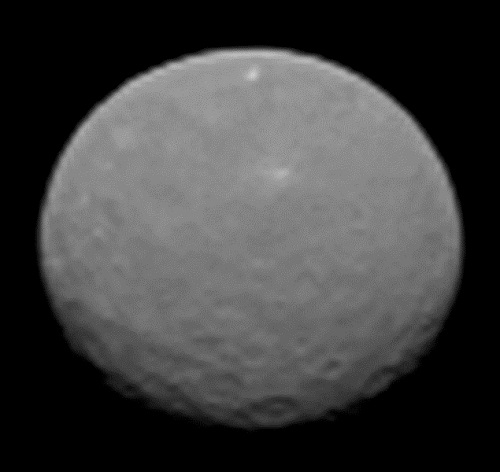

New Views of Ceres, Pluto/Charon

Watching Ceres gradually take on focus and definition is going to be one of the great pleasures of February. The latest imagery comes from February 4, with the spacecraft having closed to about 145,000 kilometers. Here we’re looking at a resolution of 14 kilometers per pixel, the best to date, but only a foretaste of what’s to come. For perspective, keep in mind that while Ceres is the largest object in the main asteroid belt, its diameter is a scant 950 kilometers. Is there an ocean under this surface?

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA/PSI.

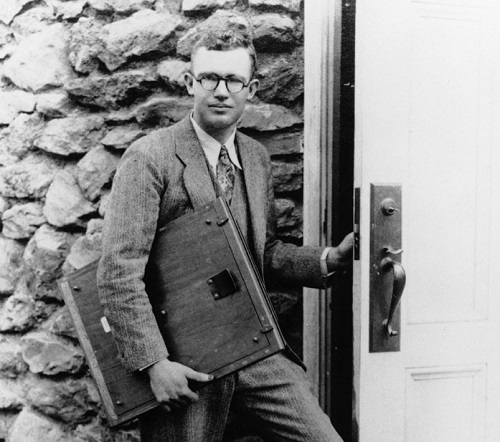

Meanwhile, a good deal further out in the system, a small vial of Clyde Tombaugh’s ashes continues its remarkable trek, with new imagery from New Horizons, the spacecraft carrying it, being released on the same day the Ceres images were taken, February 4, which happens to be Tombaugh’s birthday. Born in 1906, Tombaugh’s long life ended in 1997, and he has stayed very much in the thoughts of New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, who commented:

“This is our birthday tribute to Professor Tombaugh and the Tombaugh family, in honor of his discovery and life achievements — which truly became a harbinger of 21st century planetary astronomy. These images of Pluto, clearly brighter and closer than those New Horizons took last July from twice as far away, represent our first steps at turning the pinpoint of light Clyde saw in the telescopes at Lowell Observatory 85 years ago, into a planet before the eyes of the world this summer.”

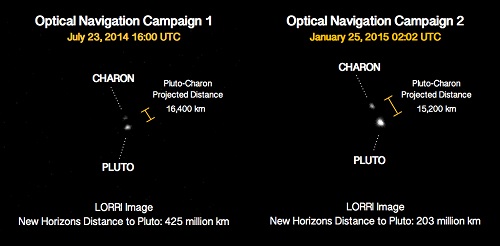

As with Ceres, we’ll be watching a distant speck turn into an actual place with features we’ll need to name as this year moves forward. The image at left, taken at a distance of over 200 million kilometers, come from New Horizons’ telescopic Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), an animation assembled from separate images taken on January 25 and January 27, which makes them the first acquired during the approach phase of the mission. The spacecraft’s flyby of Pluto/Charon takes place on July 14.

Image: A long distance look from LORRI: Pluto and Charon, the largest of Pluto’s five known moons, seen Jan. 25 and 27, 2015, through the telescopic Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) on NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft. New Horizons was about 203 million kilometers from Pluto when the frames to make the first image were taken; about 2.5 million kilometers closer for the second set. These images are the first acquired during the spacecraft’s 2015 approach to the Pluto system, which culminates with a close flyby of Pluto and its moons on July 14. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

So now New Horizons is giving us Pluto at the 2-pixel level, with Charon subtending 1 pixel as seen by LORRI, which JHU/APL describes as ” essentially a digital camera with a large telephoto telescope.” The exposure time here is one-tenth of a second, too short to make any of Pluto’s other moons, much smaller than Charon, visible. We’ll have the satisfaction of watching this system grow in our field of view over the coming months. Along the way, New Horizons will take many images of Pluto against background stars to refine distance estimates and plan course corrections needed for the flyby.

Image: Six Months of Separation: A comparison of images of Pluto and its large moon Charon, taken in July 2014 and January 2015. Between takes, New Horizons had more than halved its distance to Pluto, from about 425 million kilometers to 203 million kilometers. Pluto and Charon are four times brighter than and twice as large as in July, and Charon clearly appears more separated from Pluto. These two images are displayed using the same intensity scales. In LORRI’s current view, Pluto and Charon subtend just 2 pixels and 1 pixel, respectively, compared to 1 pixel and 0.5 pixels last July. The images were magnified four times to make Pluto and Charon more visible. Both images were rotated to show the celestial north pole at the top. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

As to Clyde Tombaugh, whenever I think of him, I think of Michael Byers’ splendid portrait in his novel Percival’s Planet (Henry Holt, 2010), although to be sure, Byers focuses not just on Tombaugh but on the entire enterprise of planet-finding and the nature of obsession (the latter being Percival Lowell’s fixation on ‘Planet X’ as well as the private demons of his subordinates). My earlier review of Percival’s Planet is here. Tombaugh was a Kansas farmboy who could grind lenses like no one else, a self-educated master craftsman whose eye for detail would change our view of the Solar System. What a pleasure to hear the words of his daughter in this New Horizons news release:

“My dad would be thrilled with New Horizons,” said Annette Tombaugh, Clyde Tombaugh’s daughter, of Las Cruces, New Mexico. “To actually see the planet that he had discovered and find out more about it, to get to see the moons of Pluto … he would have been astounded. I’m sure it would have meant so much to him if he were still alive today.”

My favorite photograph of Tombaugh has always been the one above (from the collection at New Mexico State University). Look at the sheer determination in that face! This is a man who knows what he is about — I wish I had known him.

On the Role of Humans in Starflight

What does it take to imagine a human future among the stars? Donald Goldsmith asks the question in a recent op-ed for Space.com called Does Humanity’s Destiny Lie in Interstellar Space Travel, playing off the tension between successful robotic exploration that has taken us beyond the heliosphere and the human impulse for personal experience of space. Along the way he looks at options for star travel both fast (wormholes) and slow (nuclear pulse, or Orion).

A fine science writer who worked with Neil deGrasse Tyson on Origins: Fourteen Billion Years of Cosmic Evolution, Goldsmith nails several key issues. The successes of robotic exploration are obvious, and we’re in the midst of several more energizing episodes — the arrival of Dawn at Ceres and the approach of New Horizons to Pluto/Charon, as well as the recent cometary exploits of Rosetta. We have much to look forward to and, as mentioned yesterday, new impetus has arisen for the Europa Clipper mission, which would constitute a fine tandem operation with the ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer.

Freeman Dyson, in fact, thinks the success of robotics is so marked that the real work will necessarily be done by machines, with human travel in space in the category of entertainment rather than science. But Goldsmith finds this unsatisfying, and I think he speaks for quite a few people when he says a human presence on places like Mars speaks to our deepest impulses:

Just about everyone welcomes new information about the solar system, but what many really — really — want is for humanity to plant its boots on new soil, as Earth-bound explorers have done for many centuries. Lonely humans in space speak directly to our emotions, but pioneering spacecraft far less so. (Even an apparent exception, such as the hero of the movie “WALL-E,” connects with us through its seeming humanity, a fact that won’t surprise anyone who reflects for a moment on how storytelling works.)

Machines get more powerful at a mind-numbing pace, while the evolutionary changes that help us adapt to new environments move with far slower rhythms. Hybrids of human and machine may one day be feasible, or some kind of mind-uploading (a prospect I still think unworkable, as it tries to fit a consciousness that is the result of evolution in a physical body into an alien matrix). There is also the prospect of artificial intelligence achieving human-like capabilities, as witness the poetic, deeply introspective star-probe of Greg Bear’s novel Queen of Angels.

But for those who insist upon human bodies aboard a starship, these options aren’t enough, which leads us to the confrontation with the reality of distance, the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, being approximately 260,000 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun. Goldsmith takes a look at the Project Orion study in which Dyson played such a major role, envisioning a spacecraft that would be driven by a series of nuclear explosions behind the craft, their energies extracted by a pusher plate and a crew-saving system of enormous shock absorbers.

Image: An early conception of Orion as an interplanetary vehicle, one that would eventually be reworked into Freeman Dyson’s interstellar design. Credit: Adrian Mann.

Dyson’s 1968 paper on the ultimate Orion, a starship capable of reaching the nearest stars in 140 years, gave us what Goldsmith calls ‘the gold standard for visions of interstellar travel,’ in that Orion used technologies not impossibly far from what was currently available. But it’s telling that Dyson still sees the key requirement for interstellar flight as a society that can think in terms of centuries and work with long-term planning and execution of generational projects. Orion ran afoul of test ban treaties and the ever-controversial issue of radiation, but in any case it’s hard to see a culture with such short time-horizons as ours building such a vessel.

I’m glad to see Goldsmith referring to Steve Kilston’s ideas on slow expansion, which throws out the false dichotomy between fast results or none at all. Kilston’s idea is best described as a worldship, one we’ve looked at before in these pages. An astronomer and something of a philosopher, Kilston believes that within 500 years we will be able to build a vast structure capable of carrying a million people on a journey at a small fraction of the speed of light. It’s a generation ship, and one that banks on serious changes in the human outlook. Says Goldsmith:

Kilston’s “Plausible Path,” like any other low-velocity journey, requires that generations upon generations of spacefarers pass their entire lives short of their goal. Today, this plan would attract few volunteers. But if human society came to feel sure of its long-term viability, so that our time horizon stretched beyond the current limits of (at most) our grandchildren’s lifetimes, the situation would become quite different. Perhaps the wisest aspect of Kilston’s plan lies in its final pre-launch phase: a 100-year cruise through the solar system to demonstrate the full feasibility of the spacecraft and the willingness of its crew to pass their lives in space.

You can read more about Kilston’s ‘plausible path’ in The Ultimate Project, a presentation the scientist made at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory back in 2006. What he is arguing is that starflight will not become a reasonable expectation unless we reach a point where at least some people think that travel times of thousands of years are acceptable given the goal to be accomplished. Here I want to quote Kilston himself, from a comment he wrote on this site in 2013, responding to a suggestion that there may be reasons for interstellar flight that are irrational:

I’m not sure there is such a thing as an “irrational reason” — explanations and motivations certainly should pay attention to emotional factors. The pursuit of long-term goals and dreams is as vital for our mental and societal health as a concern and empathy for other humans is.

Children respond with wonder and enthusiasm when they hear about a grand project like interstellar travel. It can continue to magnificently inspire them long after we initiate it. As Pierre Teilhard de Chardin wrote, “The future belongs to those who give the next generation reason for hope.”

Goldsmith himself seems to be in this camp. And I think he’s practical enough to acknowledge that the outcome is very much up to us. There is no certainty that our species will ever attain interstellar flight, but if we are to make it happen, we’ll have to learn how to live off the Earth long-term. That would in my view involve ever increasing colonization within the Solar System to master the technologies needed for starflight and the human issues of survival in deep space.

At that point, I see no reason why space habitats on the scale of what Steve Kilston has long studied could not be built, either as explicit starships or as O’Neill-style colony worlds. Would generations accustomed to living in constructed habitats like these eventually decide to take one of their vessels all the way to another star? We have trouble imagining people who would be willing to live this way, but several centuries of technological development and experience in space could make the prospect far less onerous. I agree with Kilston that it’s a plausible path, and whether it happens or not, we still have rapidly advancing artificial intelligence to fall back on. In one form or another, I think human efforts will indeed result in interstellar journeys.

On to Europa?

With the 2016 budget cycle beginning, it’s heartening to see that Europa factors in as a target amidst a White House budget request for NASA of $18.5 billion, higher than any such request in the last four years, and half a billion dollars more than the agency received in the 2015 budget. This follows Congress’ NASA budget increase of last year. Casey Dreier, who follows space policy issues for The Planetary Society, cites what he calls a ‘new commitment to Europa’, as seen in a request for $30 million to start the mission planning process. Dreier adds:

At its most basic level, it means that NASA can pursue the development process to create a mission to explore Europa. That’s new, and that’s important. Europa has moved from “mission concept” to “mission,” with details to figure out, plans to draw, teams to assemble, and hardware to build (eventually). It’s a step that Congress could not force NASA to take (NASA being an executive branch agency and all) no matter how much money it gave to them. The White House and NASA deserve credit for deciding to pursue this mission. In fact, I believe that this budget will occupy a small place in history as document that officially began the exploration of Europa.

I leave you to Dreier’s analysis for details about other budget components so we can focus this morning on Europa. But do keep in mind that while we’re only at the beginning of a budget debate, documents like these are nonetheless critical in setting the terms under discussion and keeping key mission ideas current. While we’ve seen huge changes in direction and mission targets over the past fifteen years, the persistence of Europa as a focus for robotic exploration is heartening, and it’s a focus buttressed by the outstanding results from Cassini at Saturn.

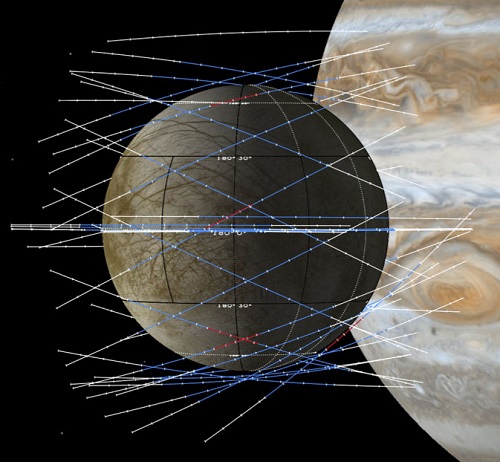

The Europa Clipper mission that may emerge from all this bears in its projected operations a certain similarity to Cassini, in that over the years since the latter began orbiting Saturn, we’ve learned a huge amount about Saturn’s moons from flybys. Just as Cassini has opened up detailed study of Titan, Europa Clipper would be an orbiter that would make forty to fifty flybys of Europa’s surface during its primary mission. This will demand a highly elliptical orbit aimed at minimizing radiation damage and a spacecraft heavily shielded against dangerous particles.

Image: Concept to achieve “global-regional coverage” of Europa during successive flybys. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

So no landing on Europa — not at this stage of the game — but a series of close Europa flybys at altitudes ranging from 2700 kilometers down to 25 kilometers would give us priceless information. If the moon really does have geysers that vent water from the presumed deep ocean below the ice, a spacecraft this close to the surface could take samples, in addition to giving us close-up views of the reddish veins that so distinctively mark the crust, possibly containing organic compounds that may be involved in cycling between surface and sea.

Also positive is the news that the current budget request will contain funding for the instruments NASA intends to contribute to the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer mission (JUICE), which is to launch in 2022 (see Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer). Arriving in Jupiter space in 2030, the mission is to spend several years studying not just Europa but Ganymede and Callisto as well, all three being candidates for subsurface oceans. After flybys of Europa and Callisto, (including measurements of the thickness of Europa’s crust), the spacecraft will enter orbit around Ganymede to study the surface and structure of the only Solar System moon known to generate its own magnetic field.

This JPL page on Europa Clipper notes that it too would make flybys of Ganymede and Callisto, but only for the sake of orbital adjustments, the primary mission being Europa. There, the campaign would consist of four segments designed to produce maximum coverage of the surface under consistent lighting conditions. From the document:

During each flyby, a preset sequence of science observations would be executed. On approach the spacecraft would perform low-resolution global scans with its IR spectrometer (“nodding” the spacecraft’s field of view back and forth across the moon, much like the Cassini spacecraft does during its moon flybys), followed by high-resolution scans with that instrument. At 1,000 km the ice-penetrating radar, topographic imager and ion and neutral mass spectrometer (INMS) would power up. The radar pass would occur from 250 miles (400-km) inbound altitude to 250 miles (400-km) outbound altitude, during which stereo imaging and INMS data are acquired continuously. During departure, the IR spectrometer would conduct additional high- and low-resolution scans as the spacecraft moves away from Europa.

And apropos of yesterday’s discussion of CubeSats, I want to note that NASA is looking at proposals from ten universities for CubeSat concepts to enhance Europa Clipper, an announcement that was made last October. The idea here is to carry small probes as auxiliary payloads that would be released in the Jovian system for further measurements of Europa. According to the agency, the science objectives for potential CubeSat probes include reconnaissance for future landing sites, gravity fields, magnetic fields, atmospheric and plume science, and radiation measurements. The latter may be a showstopper, in my view, given the radiation environment in which these diminutive spacecraft would be forced to operate.

So the outer planet news is at least momentarily positive, and as Phil Plait reminds us in NASA Has Its Sights Set on Europa, the Europa Clipper mission has a strong champion in Congress in Rep. John Culberson (R-Texas), whose support has been useful to NASA in past debates. With a launch in the early 2020s and a 6.5-year journey to Jupiter that includes gravity assists around Venus and (twice) the Earth, Europa Clipper could open up the next phase of outer planet exploration, followed shortly thereafter by the arrival of JUICE. That would make the years around 2030 a golden era for our understanding of Jupiter’s provocative moons.

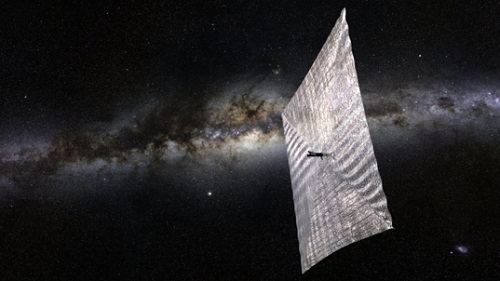

Looking Ahead to LightSail

The news that The Planetary Society is readying the first of its Lightsail spacecraft for a May launch stirs memories of Cordwainer Smith (Paul Linebarger) and mainframe computers. Smith wrote his haunting science fiction in the days when computers filled entire rooms, and the pilot who flies a solar sail thousands of kilometers wide in “The Lady Who Sailed the Soul” is there because, as a technician tells her, “…a sailor takes a lot less weight than a machine. There is no all-purpose computer built that weighs as little as a hundred and fifty pounds. You do. You go simply because you are expendable.”

Despite the anachronisms, Smith’s short stories (collected in The Rediscovery of Man) are as mesmerizing as ever. As computers were big in those days, so have been our sail designs, from Smith’s behemoth (towing 26,000 adiabatic pods containing frozen human settlers) to Robert Forward’s beamed-laser sails. Given the need for harnessing the momentum of photons, all this makes sense, but we’re learning how many interesting things we can do with much smaller sails, like NASA’s NanoSail-D, an experiment in sail deployment and de-orbiting payloads that was a scant 10-meters square. LightSail, in sail terms, is still quite small, with a combined area of 32 square meters.

Both NanoSail-D and LightSail take advantage of the wild card technology of recent times, the CubeSat, which allows sails to be packed into containers no larger than a loaf of bread. Each of the mylar sails aboard the LightSail mission — there are four of them — is about 4.5 microns thick, deploying from four metallic booms that gradually unwind to unfold the triangular sail panels. The craft will use three electromagnetic torque rods to interact with the Earth’s magnetic field to maintain proper orientation. After sail deployment, ground-based lasers will measure the solar photon effect.

Image: LightSail-1 fully deployed. The mission is a precursor to a later LightSail mission to test true solar sailing in a much higher orbit. Credit: Josh Spradling/The Planetary Society.

The Planetary Society is calling this mission a ‘shakedown cruise,’ one that will allow scientists to test out the basic functions of the mission in preparation for the launch of a second LightSail in 2016 aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy. A four-week checkout period will be followed by sail deployment, after which, because of its low orbit, the craft will be pulled within days back into the atmosphere. Even so, we should get interesting views of the deployment through LightSail’s two inward-facing cameras, offering time-lapse imagery of the sail’s brief period of operations.

In Jason Davis’ recent article on LightSail, he notes a fact that many of us vividly recall. It will be ten years this June since the Russian Volna rocket carrying The Planetary Society’s Cosmos 1 failed in its attempt to lift the sail to orbit. That left the Japanese space agency JAXA to win the honor of achieving the world’s first operational solar sail when it launched IKAROS in 2010. But interest in small sail technology remains intense, with NASA planning both NEA Scout and Lunar Flashlight for launch in 2018. Both are CubeSat-based, though with larger sails than LightSail. For more on sail projects now in development, see A Near-Term Sail Niche. Note as well that The Planetary Society has created a new website for the two LightSail missions.

But even 85-square meter sails like NEA Scout and Lunar Flashlight are tiny compared to the 1000-kilometer lightsail Robert Forward envisioned for a manned mission to Epsilon Eridani. Can we really do worthwhile science with sails this small? The answer is a resounding yes. By reducing payload mass and maximizing the power of miniaturization, CubeSats give us options like ‘swarm’ missions to the outer Solar System that could be enabled by sail technologies. This could be a low-cost approach to deepening our knowledge of places we’ve only seen in flybys.

So as we continue work on larger designs, let’s see what we can learn from small sails close to home. When LightSail deploys, I’ll probably go back and re-read “The Lady Who Sailed the Soul,” where Cordwainer Smith describes “…the great sails, tissue-metal wings with which the bodies of people finally fluttered out among the stars.” Our CubeSat sails are early steps along the road to the great ships of Smith, Robert Forward and all the researchers who have seen the promise of sunlight and beamed energy as ways to push our payloads into the cosmos.

A Review of the Best Habitable Planet Candidates

The fascination with finding habitable planets — and perhaps someday, a planet much like Earth — drives media coverage of each new, tantalizing discovery in this direction. We have a number of candidates for habitability, but as Andrew LePage points out in this fine essay, few of these stand up to detailed examination. We’re learning more all the time about how likely worlds of a given size are to be rocky, but much more goes into the mix, as Drew explains. He also points us to several planets that do remain intriguing. LePage is Senior Project Scientist at Visidyne, Inc., and also finds time to maintain Drew ex Machina, where these issues are frequently discussed.

by Andrew LePage

The past couple of years have been eventful ones for those with an interest in habitable extrasolar planets. The media have been filled with stories about the discovery of many new extrasolar planets that have been billed as being “potentially habitable”. Unfortunately follow-up observations and new insights into the properties of planets larger than the Earth have cast doubts on some of these initial optimistic proclamations that have been largely ignored by the media and other outlets. With all the new information available, I figured it was a good time to make an objective reevaluation of the potential habitability of a number of extrasolar planets that have made the headlines in recent years.

Basic Habitability Criteria

A thorough assessment of the habitability of any extrasolar planet would require a lot of detailed data on the properties of that planet, its atmosphere, its spin state and so on. Unfortunately, at this very early stage, the only information typically available to scientists about extrasolar planets is basic orbit parameters, a rough measure of its size or mass and some important properties of its sun. Combined from theoretical extrapolations of the factors that keep the Earth habitable, the best we can hope to do at this time is to compare the known properties of extrasolar planets to our current understanding of planetary habitability to determine if an extrasolar planet is “potentially habitable”. And by “habitable”, I mean habitable in an Earth-like sense where the surface conditions allow for the existence of liquid water on the planet’s surface. While there may be other worlds that might possess environments that could support life (e.g. Mars or the tidally heated moons Europa and Enceladus), these would not be Earth-like habitable worlds of the sort being considered here.

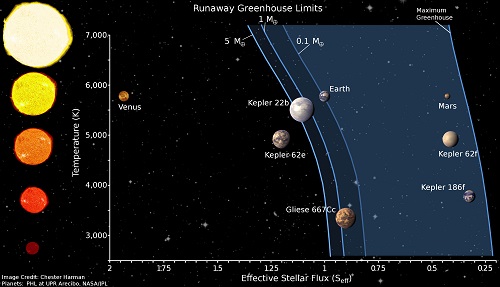

One of the key pieces of information we have available for extrasolar planets to assess their potential habitability is their effective stellar flux (or Seff where Earth’s value is defined as 1). This can be readily calculated using information about a planet’s orbit and the luminosity of its sun. If this effective stellar flux falls within a range corresponding to the limits of a sun’s habitable zone (HZ), this planet has met one of the basic criteria for potential habitability.

One of the more better known definitions for the limits of the habitable zone as defined by the work of James Kasting (Pennsylvania State University) starting over two decades ago is based on an extrapolation of our knowledge of the processes that have kept our own planet habitable over the last several billion years despite a 30% increase in the Sun’s luminosity. The latest refinements of this work by Ravi Kopparapu (Pennsylvania State University) and his collaborators define the inner limit of the HZ to correspond to the Seff where a moist runaway greenhouse effect sets in. At higher effective stellar flux values, skyrocketing surface temperatures and the loss of a planet’s allotment of water in a geologically brief period of time will result. For an Earth-size planet orbiting a Sun-like star, this limit corresponds to an Seff of about 1.11. The Seff corresponding to this inner limit of the HZ would be slightly higher for planets more massive than the Earth and slightly lower for stars cooler than the Sun.

There have been models proposed over the past decade and more with higher effective stellar flux values for the inner limit of the HZ in cases of synchronous rotation (which would be common for planets orbiting in the HZs of red dwarfs) and a range of other special circumstances. Such definitions have been attractive to some hoping to maximize the chances that a new find might be considered to be habitable. However, these sometimes involve extreme extrapolations from conditions here on Earth or contrived special circumstance. In general, these definitions require more study and some reliable empirical observations to be on a firmer theoretical footing like the work by Kopparapu et al.. In a recent paper by Kasting and Kopparapu et al., it is argued that while there is certainly genuine uncertainty on the precise inner limit of the HZ as a result of limitations of the simple models used to date, some of the most optimistic inner limit definitions involve scenarios that are physically unrealistic. As result, I personally tend to favor the more conservative definition of the inner limits of the HZ.

The outer limit of the HZ, as defined by Kopparapu et al., corresponds to the maximum greenhouse limit beyond which a CO2-dominated greenhouse is incapable of maintaining a planet’s surface temperature. The latest work suggests an Seff value of about 0.36 for a Sun-like star with cooler stars having slightly lower values. As with the inner limit of the HZ, there are some slightly more optimistic definitions of the outer edge of the HZ such as the early-Mars scenario or evoking some sort of super-greenhouse where gases other than just CO2 contribute to warming a planet. But these more optimistic definitions do not change the Seff for the outer limit of the HZ significantly.

Another important parameter we have available today to gauge the potential habitability of an extrasolar planet is its mass (or MP) derived from precision radial velocity measurements or its radius (or RP) calculated from observations of planetary transits. In the case of the radial velocity measurements, we actually only know the planet’s MPsini value where i is the inclination of the orbit with respect to our line of sight. Since the inclination can not be determined directly from radial velocity measurements alone, we can only know the planet’s minimum mass or the probability that the actual mass is in some range of interest. By definition, the actual mass of a planet with an unconstrained orbit inclination is most likely larger than this minimum mass – in some case it can be much larger.

A series of analyses of Kepler data and follow-up observations published over the last year have shown that there are limits on how large a rocky planet can become before it starts to possess increasingly large amounts of water, hydrogen and helium as well as other volatiles making the planet a Neptune-like world with no real prospect of being habitable. Work performed by Leslie Rogers (a Hubble Fellow at the California Institute of Technology) has shown that planets with radii greater than no more than 1.6 times that of the Earth (or RE) are most likely mini-Neptunes. This and other recent work suggests that this transition corresponds to planets with masses greater than about 4 to 6 times that of the Earth (or ME). As a result, planets larger or more massive than these empirically-derived thresholds are unlikely to be rocky planets never mind habitable. On the other hand, recent work submitted for publication by a team led by Courtney Dressing (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) strongly suggests that worlds smaller than this threshold will usually have an Earth-like composition. For a more thorough discussion of this work, see The Composition of Super-Earths and my earlier Centauri Dreams post The Transition from Rocky to Non-Rocky Planets.

Image: This diagram illustrates how the boundaries of the HZ as defined in the work of Kopparapu et al. vary as a function of star temperature and planet mass. Several potentially habitable extra solar planets are included. Credit: Chester Harman/PHL/NASA/JPL.

With these basic criteria available, it is possible to start to gauge the potential habitability of an extrasolar planet. For this review, I wanted to use a well-regarded catalog of potentially habitable planets. The University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo Planetary Habitability Laboratory maintains a web site which currently lists 28 extrasolar planets in 23 systems in their Habitable Exoplanets Catalog along with many more currently unconfirmed planets that will not be considered here. The reviews that follow use this list of confirmed extrasolar planets and the data it contains except where noted.

EPIC 201367065d: RP=1.5 RE, Seff=1.51

This extrasolar planet is among the first new worlds found during Kepler’s extended “K2” mission with its discovery just announced by Crossfield et al. in a paper submitted for publication. As I write this, it has yet to make it into the “Habitable Exoplanet Catalog” but I am including it here because it is bound to be added shortly since it seems to have properties similar to other worlds already in the catalog.

With a radius of 1.5 RE, this EPIC 201367065d is just below the threshold dividing rocky and Neptune-like planets making it more likely to have an Earth-like composition. Unfortunately, its high effect stellar flux places it well beyond the inner boundary of the HZ as it is more conservatively defined for a red dwarf star. But given the uncertainties in its properties, I estimate that there is still about a one in eight chance of it actually orbiting inside even the conservatively defined HZ. While I consider EPIC 201367065d to be a poor candidate for being potentially habitable at this time, its sun is relatively nearby and bright making it a good candidate for follow up observations that can provide some hard data about the properties of worlds like this.

GJ 163c: MPsini=7.3 ME, Seff=1.40

GJ 163c was discovered in 2012 using precision radial velocity measurements. As a result, we only know that its minimum mass is 7.3 ME. Given that this value is already exceeds the 6 ME threshold that seems to divide large rocky planets from mini-Neptunes and that this planet’s actual mass is probably higher still, it is unlikely that GJ 163c is a rocky planet. Combined with its high effective stellar flux that is larger than the more conservative definitions of the HZ, it seems improbable that GJ 163c is a potentially habitable, Earth-like world.

GJ 180b: MPsini=8.3 ME, Seff=1.23

GJ 180c: MPsini=6.4 ME, Seff=0.79

GJ 180 is a system thought by some to contain a pair of potentially habitable planets. While GJ 180c appears to orbit comfortably inside the inner part of the HZ of this system, GJ 180b seems to orbit just a little too close to be considered habitable using the more conservative definition of the HZ. Unfortunately, with measured minimum masses of 8.3 ME and 6.4 ME for GJ 180b and c, respectively, it is highly unlikely that either of these planets have rocky compositions. Given that these planets’ actual masses are probably much higher than this, it is more likely they are mini-Neptunes or larger with little prospect of being potentially habitable.

GJ 442b: MPsini=9.9 ME, Seff=0.70

GJ 442b is yet another example of a planet that seems to orbit inside the HZ of its sun no matter how it is defined but it is too massive to likely be a rocky planet. Radial velocity measurements indicate that this planet has a minimum mass of 9.9 ME which makes it much more likely to be a mini-Neptune. In fact, given the uncertainty in the inclination of its orbit to our line of sight, there are better than even odds that GJ 442b is Neptune-size or even larger. As a result, GJ 442b is highly unlikely to be a potentially habitable planet.

GJ 667Cc: MPsini=3.8 ME, Seff=0.88

GJ 667Ce: MPsini=2.7 ME, Seff=0.30

GJ 667Cf: MPsini=2.7 ME, Seff=0.56

GJ 667C has been in the news a lot recently because of the belief that it contains as many as seven planets discovered using precision radial velocity measurements. Initial assessments hinted that three of the planets in this packed system might be potentially habitable – GJ 667Cc, e and f. Unfortunately, follow-up work performed on this promising planetary system now strongly suggests that it does not contain any potentially habitable planets at all.

A series of independent analyses of the radial velocity data for GJ 667C culminating in the work by Paul Robertson and Suvrath Mahadevan (Pennsylvania State University) now indicates that the radial velocity variations originally interpreted as being the result of as many as seven planets are in fact caused by only two planets. It now seems likely that surface activity on GJ 667C modulated by its 105-day rotation period is responsible for mimicking the subtle radial velocity signature of the other supposed planets including the potentially habitable GJ 667Ce and f. A similar situation was encountered last year with the habitable planets of GJ 581 which these same investigators also found to be the result of stellar activity masquerading as planets. While more follow-up work is required, it now seems likely that GJ 667C and f do not exist.

While the existence of GJ 667Cc seems to be secure, unfortunately its potential habitability appears to have been overstated. Based on its Seff value, GJ 667Cc seems to be safely inside the inner portions of this star’s HZ. However, since this planet was discovered using radial velocity measurements, we currently only know that its minimum mass is about 4.1 ME based on the work by Robertson and Mahadevan. Given the currently unconstrained inclination of its orbit to our line of sight, there is only a one in three chance that this world has a mass less than the 6 ME threshold dividing predominantly rocky worlds from mini-Neptunes. It is much more probable that GJ 667Cc is a mini-Neptune with little chance of being potentially habitable.

If GJ 667Cc beats the odds and is a rocky planet after all, it is still unlikely to be a promising habitable planet candidate. Investigation of the spin state of GJ 667Cc performed by Valeri Makarov and Ciprian Berghea (US Naval Observatory) strongly suggests that this world is experiencing excessive tidal heating due to the high eccentricity of its small orbit around its primary. Makarov and Berghea estimate that if GJ 667Cc has an Earth-like composition, tidal heating would generate about 300 times the heat flow as the Earth experiences melting its mantle and crust in the process. Given the two most likely possibilities, it seems highly improbable that GJ 667Cc is a potentially habitable world. For a more detailed discussion of this system, see Habitable Planet Reality Check: GJ 667C.

GJ 682c: MPsini=8.7 ME, Seff=0.37

Based on an analysis of the radial velocity of GJ 682, it appears that GJ 682c orbits near the outer limits of the HZ of this system. But once again, with a minimum mass of 8.7 ME and an actual mass that is probably much higher, it is highly unlikely that GJ 682c is a rocky planet. Given an unconstrained orbit inclination, it has about an even chance of being Neptune-size or larger. It is therefore very unlikely that GJ 682c is potentially habitable.

GJ 832c: MPsini=5.4 ME, Seff=1.00

In 2014, a team led by Robert Wittenmyer (UNSW Australia) announced the discovery of a planet orbiting GJ 832 using precision radial velocity measurements. Given the properties of this world, Wittenmyer et al. specifically stated in their discovery paper that they did not believe that their find was a potentially habitable planet and it was more likely to be a uninhabitable super-Venus instead. This candid assessment was ignored by some who argued that GJ 832c is among the most Earth-like planets known. The effective stellar flux of GJ 832c places this world just inside the inner edge of this system’s conservatively defined HZ. Even if we were to expand the HZ limits based on more optimistic definitions of the HZ, the 5.4 ME minimum mass of GJ 832c gives it a 90% probability of exceeding the 6 ME mass threshold dividing Earth-like and Neptune-like planets. As a result, it is improbable that GJ 832c is a rocky planet never mind a potentially habitable one. For a more detailed discussion of this planet, see GJ 832c: Habitable Super-Earth or Super Venus?.

GJ 3293b: MPsini=8.6 ME, Seff=0.60

GJ 3293b is yet another example of a world that seems to orbit comfortably inside the HZ but has almost no chance of being habitable due to its excessive mass. Based on precision radial velocity measurements, GJ 3293b has a minimum mass of 8.6 ME which already exceeds the 6 ME mass threshold where it is more likely that a planet is a mini-Neptune instead of a rocky planet. With an unconstrained orbit inclination, there are about even odds that this planet is actually Neptune-size or larger. As a result, it is highly improbable that GJ 3293b is potentially habitable.

HD 40307g: MPsini=7.1 ME, Seff=0.68

The situation with HD 40307g is comparable to that of GJ 442b, GJ 682c and GJ 3293b: the planet seems to orbit comfortably inside the HZ but it is most likely a mini-Neptune or larger planet. With a minimum mass of 7.1 ME derived from radial velocity measurements and an unconstrained inclination, it is unlikely that HD 40307g is a potentially habitable planet.

Kapteyn b: MPsini=4.8 ME, Seff=0.43

Kapteyn’s Star is an ancient, nearby red sub-dwarf only 12.8 light years away. Last year’s announcement of the discovery of two planets orbiting this star promises important insights into the planet formation process during the earliest history of our galaxy. One of those two planets, Kapteyn b, was widely claimed to be the oldest potentially habitable planet yet discovered. Looking at this world’s effective stellar flux, it seems to be comfortably inside the outer part of this star’s HZ. But since it was discovered using precision radial velocity measurements, we only have a minimum mass value of 4.8 ME. With an unconstrained orbit inclination, there is an 80% probability that its actual mass exceeds 6 ME making it more likely to be a mini-Neptune rather than a rocky planet. As a result, it is unlikely that Kapteyn b is a potentially habitable planet. For a more detailed discussion of this planet, see Habitable Planet Reality Check: Kapteyn b.

Kepler 22b: RP=2.4 RE, Seff=1.11

Like so many planets found using radial velocity measurements, there have also been worlds discovered by NASA’s Kepler mission that were initially considered potentially habitable by some but turn out to be too large after more detailed analyses of planet properties have become available. The effective stellar flux of Kepler 22b places it just beyond the inner edge of a conservatively defined HZ. But with a radius measured to be 2.4 RE, which easily exceeds the 1.6 RE threshold where planets are no longer likely to be rocky, it is very unlikely that Kepler 22b is a potentially habitable planet and more likely to be a volatile-rich mini-Neptune instead.

Kepler 61b: RP=2.2 RE, Seff=1.27

Kepler 61b is in a similar situation as Kepler 22b: its effective stellar flux appears to be a bit too high to be considered inside the conservative definition of the HZ and its large radius of 2.2 RE makes it unlikely to be a rocky planet. As with Kepler 22b, Kepler 61b is very unlikely to be a potentially habitable planet and more likely to be a mini-Neptune.

Kepler 62e: RP=1.6 RE, Seff=1.10

Kepler 62f: RP=1.4 RE, Seff=0.39

After reading one disappointing review after another so far, the reader might begin to think there are no potentially habitable planets currently known. Fortunately, there is the multi-planet system of Kepler 62. Kepler 62e appears to orbit just beyond the inner edge of this star’s HZ and with a radius of 1.6 RE, it has about even odds of actually being a rocky planet. Taking into account the uncertainty of the actual inner limit of the HZ, it seems that Kepler 62e is a fair candidate for being a potentially habitable planet.

The situation for Kepler 62f appears even better. With a radius of 1.4 RE, which is comfortably below the 1.6 RE dividing line between Earth-like and Neptune-like planets, there is a good chance that Kepler 62f is a rocky planet. Combined with its effective stellar flux that places it in the outer part of even a conservatively defined HZ, it appears that Kepler 62f is among the better potentially habitable planet candidates currently known.

Kepler 174d: RP=2.2 RE, Seff=0.43

Like so many other planets initially considered to be potentially habitable by some, Kepler 174d seems to orbit well inside the HZ but it appears to be too large to be a rocky planet. With a radius of 2.2 RE, it is much more likely that Kepler 174d is a volatile-rich mini-Neptune with poor prospects of being potentially habitable.

Kepler 186f: RP=1.2 RE, Seff=0.29

When its discovery was announced last year, Kepler 186f generated much attention because of its Earth-like size and its orbit inside the HZ of its red dwarf sun. Recently published refinements of its properties by a team led by Guillermo Torres (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) in the same paper where they just announced the discovery of eight new habitable zone planets has only reinforced the case for the potential habitability of Kepler 186f. Its effective stellar flux places it towards the outer edge of the HZ of this system. Its radius of 1.2 RE, which is comfortably below the 1.6 RE limit that divides Earth-like planets from Neptune-like planets, makes it probable that it is a rocky planet. So long as no major impediments to habitability of planets orbiting red dwarfs are revealed, Kepler 186f is one of the best habitable planet candidates currently known. For a more detailed discussion of this world, see Habitable Planet Reality Check: Kepler 186f.

Kepler 283c: RP=1.8 RE, Seff=0.90

Kepler 283c is one of those planets that is frustratingly close to being potentially habitable but just doesn’t quite make it. The effective stellar flux of Kepler 283c places it near the inner edge of its sun’s HZ. But with a radius measured to be 1.8 RE, it is more likely to have a volatile-rich instead of rocky composition. Kepler 283c only has a fair chance at being potentially habitable.

Kepler 296e: RP=1.5 RE, Seff=1.22

Kepler 296f: RP=1.8 RE, Seff=0.34

When the discovery of planets in this system was first announced in 2014, Kepler 296f was considered by some to be a good habitable planet candidate. But follow-up observations of this star soon revealed that instead of it being a single star, it consisted of a pair of red dwarf stars instead that appear blended together as viewed by Kepler. As a result, the properties of its planets which had been derived assuming a single star were no longer valid. Additional work by Torres et al. has been able to resolve this issue and they derived properties that would make both Kepler 296f and e habitable planet candidates.

A closer look at this work, however, casts some doubt on this assessment. With a radius of 1.5 RE, which is smaller than the 1.6 RE size limit for rocky planets, Torres et al. calculated that there is 50.7% probability of Kepler 296e being a rocky planet. While they calculated a high probability that Kepler 296e orbits inside the HZ, they were using a very optimistic definition of the HZ that placed the inner edge of the HZ where the effective stellar flux was 50% higher than Venus experiences today. Given the uncertainties in this world’s derived orbital properties, I estimate that there is only one chance in four that it actually orbits inside the HZ as it is more conservatively defined. Unless the predictions of models of a more optimistic definition of the inner limit of the HZ are borne out, it seems more likely that Kepler 296e is a larger but cooler version of Venus and is only a fair habitable planet candidate.

The situation for the more distantly orbiting Kepler 296f is a bit more promising in some ways. The effective stellar flux for this planet places it comfortably inside the outer part of its sun’s HZ. However, with a radius of 1.8 RE, Torres et al. estimate that there is only a 30.6% probability that Kepler 296f is a rocky world. Because of this, Kepler 296f is only a fair potentially habitable planet candidate

Kepler 298d: RP=2.5 RE, Seff=1.29

This world’s high effective stellar flux places it well outside the conservative definition of the HZ. But even if more optimistic limits prove to be true, its large radius of 2.5 RE makes it much more likely that it is a mini-Neptune. As a result, Kepler 298d has a very low probability of being a potentially habitable planet.

Kepler 438b: RP=1.1 RE, Seff=1.38

Kepler 438b is one of the eight extrasolar planets recently announced by Torres et al. as orbiting inside the HZ. While they estimate that there is a very high 69.6% probability of being a rocky planet owing to its small 1.1 RE radius, their assessment of the potential habitability of this world is based on the very optimistic definition of the HZ they adopted in their paper that would comfortably include Venus in our own solar system (which is most definitely not a habitable planet). Assuming a more conservative definition of the HZ limits and taking into account the large uncertainties in its properties, I roughly estimate that there is only one chance in four that Kepler 438b actually orbits inside the HZ. Given this, it appears that Kepler 438b is a poor candidate for being potentially habitable and is more likely to be a slightly larger and cooler version of Venus than an Earth-like planet.

Kepler 440b: RP=1.9 RE, Seff=1.43

Another one of the new discoveries announced by Torres et al. is Kepler 440b. Given its rather large radius of 1.9 RE, Torres et al. estimate that there is only a 29.8% probability that Kepler 440b is a rocky planet making it more likely to be a mini-Neptune instead. While they calculate a high probability that this planet orbits inside the optimistic definition of the HZ they used, I estimate that there is less than even odds of this planet orbiting inside the HZ as it is more conservatively defined. Taken together, it appears that Kepler 440b is a poor candidate for being a potentially habitable planet.

Kepler 442b: RP=1.3 RE, Seff=0.70

By far, the most promising candidate for a potentially habitable planet recently announced by Torres et al. is Kepler 442b. The sun of this system, Kepler 442, is a relatively young K-dwarf star about 1,100 light years away with 61% of the mass of the Sun and 12% of its luminosity. With a radius of 1.3 RE, Kepler 442b is estimated by Torres et al. to have a 60.7% probability of being a rocky planet. Even assuming a conservative definition for the outer limit of the HZ, this world seems to have a very high probability of orbiting comfortably inside this zone. When all the current observations are considered, it appears that Kepler 442b is one of the best candidates found to date for being a potentially habitable planet.

Kepler 443b: RP=2.3 RE, Seff=0.89

Kepler 443b was the last of the eight newly confirmed planets announced by Torres et al. that appear in the “Habitable Exoplanet Catalog”. While its effective stellar flux is certainly in a range that places it inside the HZ with a high probability no matter how it is defined, it seems to be too large to be potentially habitable. With a radius of 2.3 RE, Torres et al. calculate that there is only a 4.9% probability of Kepler 443b being a rocky planet. Since it is much more probable to be a mini-Neptune, Kepler 443b is unlikely to be a potentially habitable planet.

KOI 4427b: RP=1.8 RE, Seff=0.24

One of the planets studied by Torres et al. that still remains unconfirmed is a planet currently designated KOI 4427.01. Although its detection has a 99.16% confidence level, it did not quite meet the 3-sigma detection threshold set by Torres et al. but it still seems significant enough to likely be a bona fide planet. Based on the radius of 1.8 RE, Torres et al. estimate that there is only a 27.3% probability that this is a rocky world. Combined with less than even odds of this world orbiting inside the conservatively defined outer limit of the HZ, KOI 4427b appears to be a poor candidate for being a potentially habitable planet.

Tau Ceti e: MPsini=4.3 ME, Seff=1.51

The Sun-like star Tau Ceti has generated much interest over the decades among scientists looking for habitable planets. Unfortunately its relatively high level of activity has complicated efforts to find verifiable planets orbiting this star using precision radial velocity measurements. Despite the outstanding issues, one of the purported planets of Tau Ceti announced two year ago has been claimed by some to be potentially habitable. Tau Ceti e was discovered using precision radial velocity measurements but remains unconfirmed. Ignoring this issue for the moment, the analysis of the available data yields a minimum mass of 4.3 ME which appears to be near the lower end of the mass range where rocky planets transition to volatile-rich planets. Factoring in the unconstrained inclination of this planet’s orbit, there is a two in three chance that its mass exceeds the 6 ME threshold mass making it more likely to be a mini-Neptune. Its effective stellar flux also exceeds by a fair margin that for the conservative definition of the HZ. Taking all this information together, it seems that Tau Ceti e is more likely to be a hot mini-Neptune than a potentially habitable planet. These facts along with the questionable existence of this world make Tau Ceti e to be a very poor habitable planet candidate.

Summary

Unfortunately, an objective assessment of the known properties of the planets in the Planetary Habitability Laboratory’s “Habitable Exoplanets Catalog” casts grave doubts about the potential habitability of the majority of the planets on this list. Most of them are likely too large to be habitable Earth-like planets and are much more likely to be mini-Neptunes or even larger volatile-rich planets with very poor prospects of being habitable. In all fairness, this fact has only just become appreciated by the scientific community over this past year based on analyses like those conducted by Rogers. As a result of this, Torres et al. actually calculated the probability that their new finds were rocky planets and gave refreshingly honest assessments of their finds’ prospects in their recent discovery paper. Hopefully we will see more of this welcome practice in the future.

In three cases, it appears that the potentially habitable planets do not exist. Especially in the case of GJ 667C, the radial velocity variations that had been interpreted as being the result of orbiting planets now appear to be “false positives” caused by previously unrecognized and very subtle forms of stellar activity modulated by the star’s rotation. The unconfirmed planets believed to orbit Tau Ceti are also strongly suspected to be false positives at this time.

Among the 28 planets in the “Habitable Exoplanets Catalog”, only three appear to be genuinely good candidates for being potentially habitable: Kepler 62f, Kepler 186f and Kepler 442b. Fair candidates worthy of further consideration include Kepler 62e, Kepler 283e, Kepler 296e and f as well as Kepler 438b. In the case of these latter five worlds, they might be too large or too hot to be potentially habitable. Further observations and theoretical work on planetary habitability should help resolve their status.

Unfortunately, all of these promising candidates for potentially habitable planets orbit dim K- and M-dwarf stars that present possible issues with their habitability such as synchronous rotation, stellar flare activity and high luminosity early in their diminutive suns’ lives to name just a few. But all hope for finding better candidates is certainly not lost. Besides the likely prospects of finding more habitable planet candidates orbiting dimmer stars, the continued analysis of Kepler data is sure to uncover more Earth-like planets orbiting in the HZ of Sun-like stars as well. In addition to the recently announced discovery by Torres et al. of eight planet HZ planets, there was the much quieter announcement of two Kepler planet candidates found in the HZ of two Sun-like stars (see Earth Twins on the Horizon?). While these and similar finds still require follow-up observations to confirm their planetary nature, they provide a foretaste of the bona fide Earth-like habitable planets yet to come.

General References

Ian J.M. Crossfield et al., “A Nearby M Star with Three Transiting Super-Earths Discovered by K2”, arVix 1501.03798 (submitted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal), January 15, 2015 (preprint).

Courtney D. Dressing et al., “The Mass of Kepler-93b and the Composition of Terrestrial Planets”, arVix 1412.8687 (accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal), December 30, 2014 (preprint).

James F. Kasting, Ravi K. Kopparapu et al., “Remote life-detection criteria, habitable zone boundaries, and the frequency of Earth-like planets around M and late K stars”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 111, No. 35, pp. 12641-12646, September 2, 2014 (full text).

R. K. Kopparapu et al., “Habitable zones around main-sequence stars: new estimates”, The Astrophysical Journal, Vol. 765, No. 2, Article ID. 131, March 10, 2013 (full text).

Ravi Kumar Kopparapu et al., “Habitable zones around main-sequence stars: dependence on planetary mass”, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, Vol. 787, No. 2, Article ID. L29, June 1, 2014 (preprint).

Valeri V. Makarov and Ciprian Berghea, “Dynamical evolution and spin-orbit resonances of potentially habitable exoplanet. The Case of GJ 667C”, The Astrophysical Journal, Vol. 780, No. 2, article id. 124, January 2014 (preprint).

Paul Robertson and Suvrath Mahadevan, “Disentangling Planets and Stellar Activity for Gliese 667C”, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, Vol. 793, Article ID. L24, October 1, 2014 (preprint).

Leslie A. Rogers, “Most 1.6 Earth-Radius Planets are not Rocky”, arVix 1407.4457 (submitted to The Astrophysical Journal), July 16, 2014 (preprint).

Guillermo Torres et al., “Validation of Twelve Small Kepler Transiting Planets in the Habitable Zone”, arVix 1501.01101 (submitted to The Astrophysical Journal), January 6, 2015 (preprint).

Robert A. Wittenmyer et al., “GJ 832c: A super-Earth in the habitable zone”, The Astrophysical Journal, Vol. 791, No. 2, Article id. 114, August 2014 (preprint).