Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Spaceward Ho!

How do you go about creating a straightforward, highly durable design for a spacecraft, one that is readily refuelable and offers manifest advantages for crew comfort and safety? Alex Tolley and Brian McConnell have been asking that question for some time now, coming up with an ingenious solution that could open up large swathes of the Solar System. Alex tells me he is a former computer programmer now serving as a lecturer in biology at the University of California, where he hopes to inspire the next generation of biologists. He’s also a Centauri Dreams regular who was deeply influenced by 2001: A Space Odyssey and the Apollo landings. Below, he fills us in on the details in a narrative that imagines an early trip on such a vessel.

by Alex Tolley

The covered wagon or prairie schooner is one of the iconic images of the 19th century westward migration of the American pioneers. The wagon was simple in construction, very rugged, and repairable. They were powered most often by oxen that lived on the food and water found along the trail. The cost of a wagon, oxen and supplies was about 6 months of family wages.

In 2009 my colleague Brian McConnell and I were thinking about how to open up the exploration of space in an analogous way to the opening up of the American West during the 19th century pioneering era. We were looking for an approach that, like the covered wagon, was affordable, relatively low tech, provided safety in the case of emergencies and the space environment, could “live off the land” for propulsion like oxen, and preferably was reusable so that costs could be amortised over a number of flights.

What follows is a description of the “spacecoach” from the perspective of a new crew member making a first visit to the ship that will be on a Phobos return mission.

Image: ‘Ships of The Plains’ by Samuel Colman.

————————-

Our transfer vehicle docked gently with the Martian Queen airlock. On approach, the Martian Queen resolved into 4 fat sausages, linked end to end. On either side, from bow to stern, were solar PV arrays, partially unfurled. She looked like no spaceship seen since the dawn of the space age.. There was no gleaming metal hull, and she was devoid of all the encrustations of antennae and dishes of those earlier ships. Neither were there any signs of fuel tanks holding liquid cryofuels. Instead, the hull looked dull and somewhat like an old blimp, those non-rigid airships of the early 20th century. The only sign of exterior equipment were those solar PV panels. These were lightweight, moderate performance thin film arrays, extended out on booms to face the sun and drink her rays to power the ship. They looked more like square rigged sails as they fluttered every so gently in the tenuous atmosphere remaining at her orbit.

I knew from the briefing that the Martian Queen needed about 160KW of power, requiring about 800 m2 of arrays at Mars orbit. There was also talk of the next generation “spacecoaches” replacing the PV panels with lightweight rectennas, to convert microwave beams from the orbital transmitters. Most crews didn’t trust that idea yet, but adding a lightweight rectenna was considered a good idea to back up the PVs and also compensate for the lower intensity of sunlight as the newer ships were about to explore Jupiter space. So this was the Martian Queen, the “spacecoach” that would be my home, about to make her 2nd voyage to Phobos.

Following my crew mate Vicki, I passed through the airlock and entered a large space, nearly 60 m3 in volume, shaped like a large cylinder. The interior diameter was about 4.5 meters, about the same as the mothballed Orion I’d seen back at the Cape museum.. But with a length of 10 meters, the volume was 3x larger. The Martian Queen was composed of 4 modules, providing over 200 m3 of full sea level atmosphere pressurized volume, about 2/3rds that of the old Mir space station. Touching the inner skin of the hull it felt flexible, and slightly cool to the touch. A few light taps and the resonant sounds confirmed that there was liquid behind the skin.

Vicki answered my unspoken question about the liquid in the hull. Water was sandwiched between several layers of impermeable Kevlar in the hull. The primary, and ultimately end, use of all the water was for propellant. The spacoach had originally been folded for launch in a standard Falcon 9 fairing. Each module, without any propellant, weighed just 4 tonnes including payload. This was very little and reduced the deadweight mass of the ship. Once in orbit, the interior had been inflated and the hull filled with water. Most of that water had been launched by dumb, low cost boosters, but some was being supplied from extra-terrestrial resources. Supplies from the lunar south pole were becoming increasingly available as Chevron-Petrobras’ Shackleton base was building up mining production. Exploratory vessels were also initiating operations on asteroids, with 24 Themis looking promising with confirmed surface water. In a few decades, it was expected that all water would be supplied from extra-terrestrial sources.

“Why do you put all the water in the hull, rather than in separate tanks?” I asked.

Vicki explained that the water had a number of roles, not just as propellant. The primary reason was radiation protection. The water acted as a good radiation shield, with a halving of the radiation flux with every 18 cm. Starting with about 25 cm of water in the hull, the radiation level inside the module was just 40 percent of that striking the hull. In the event of a major solar flare, the crew could also redirect the water to an interior tube to provide the best radiation shielding for the crew. It looked like that space could get very cozy for the crew, but better than suffering radiation burns.

But it didn’t end there. Micrometeoroids are a rare, but important hazard. The water acted as a shield, absorbing the energy of these grains and preventing penetration inside the hull. The tiny holes in the outer layers quickly heal too. The outer layers of water could be allowed to freeze, trapping a dense forest of fine fibers between the 2 outer fabric layers. This made a strong material, very much like pykrete [1] that offered a stiff outer hull to protect against larger impacts. At Earth’s 1 AU from the sun, reflective foils deployed over the hull allowed passive freezing of the outer layers providing both protection and a large heat sink for the engines.

A noticeable side effect of the hull architecture was the silence. There are no clicks and bangs from thermal heating stresses. Nor did the sunward side of the interior feel noticeably warmer. Thus the water was going to offer very good thermal control of the interior, with pumps in the hull circulating the water providing dynamic thermal control.

Vicki indicated that I should follow her forward to another module. This included the kitchen and dining space. There was a freezer of dried food packages that was being organized by Pieter. Enough for a long trip with a fair variety of meals.

“You seem to have ordered a lot of Boeuf Bourguignon”, joked Pieter.

I wondered when the taste of Boeuf Bourguignon would become rather tiresome after some months. Perhaps more spicy meals like curries would have been more appropriate. I noted that the water supply for rehydrating the food and drinks was connected to the hull too. Of course, I reminded myself, the hull was a huge reservoir of water, effectively inexhaustible are far as the crew was concerned, at least on the outward bound flight.

The facilities were oriented so that “down” was towards the end of the module. This was because during cruise the Martian Queen was going to be rotated, providing some artificial gravity. This made the flight much more comfortable and familiar. We could even eat off regular plates.

Vicki quickly showed me the crew quarters and bathroom in the next module. The inner skin of the hull had been moulded into shapes that could contain water. The baths and showers were also connected to the hull’s water supply. The clean water input was connected to heaters and pumps to the various faucets and shower heads. The grey water from the drains was routed to the main purifier and returned to the hull. I inquired how frequently I could take a shower? Once, twice even three times a week?

“As much as you like”, said Vicki. “There is ample water supply for a single pass through the purifier for all the crew to shower once or twice a day. If the crew is particularly extravagant, even this can be increased with greater recycling. Hygiene is a huge morale booster on these trips.”

The toilet was apparently a composting type, although suitably modified for space. This made sense. The nitrogen and phosphorus was going to be needed for the plants growing in the interior, as well as the Phobos base agricultural areas. Nitrogen and phosphorus were still valuable elements with no rich, off-Earth supplies available. Ducking back into the kitchen space, it was clear that much of the interior was given over to growing plants. They provided the needed psychological connection with Earth, helped recycle the CO2, and freshened the air, removing unpleasant volatiles. The stale, locker room smell of most spaceships was almost absent. Some plants were also growing some fresh foods. I could just imagine the value of a fresh tomato after 6 months of spaceflight!

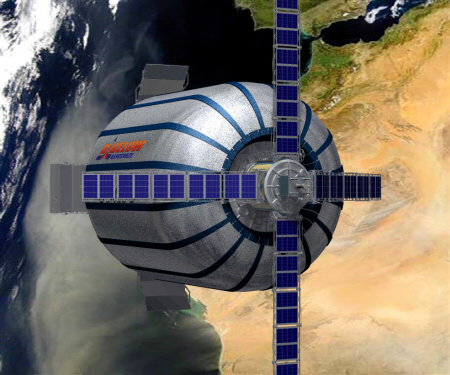

Image: The Genesis 2 space module. An inflatable habitat launched in 2007 and still operational. A design concept similar to the spacecoach. Credit: Bigelow Aerospace (http://www.bigelowaerospace.com).

Image: Inside Bigelow Aerospace Space Station Alpha mockup. This is similar to the spacecoach basic module before addition of specialized fixtures and fittings. Credit: Bigelow Aerospace.

Pulling ourselves back through the leafy interior of the modules, I looked for the engine compartment in the last module. The engines were not obvious on docking, and I wondered where they were. At the rear of the last module, an airlock was currently open, showing an enclosed space beyond. Inside, Hans, the engineer was taking apart one of the engines. He was removing a metal liner from the engine and replacing it with a fresh one. He handed the old one to me and said “carbon deposits”.

I looked closely and saw what he was talking about. Carbon deposition from contaminants in the water supply could build up in the engines, reducing performance. The engines were not much more complex than microwave ovens, although they were fitted with electric grids to further accelerate the microwave heated water plasma.

The exhaust exited via the rear, when the bay doors were opened. Now they were closed, allowing the shirt sleeve repair of the engines. I asked how frequent engine repairs were. Hans informed me that an engine needed some rework after 3-6 hours of operation. The microwave electrothermal engine performance had an Isp of about 800s, although the secondary electric grids could double that by drawing on reserve energy from the solar arrays. Vicki thanked Hans and we drifted back to the main module.

I was a little surprised at the lack of windows, but pleased that there were many flat screens where windows should have been. I looked “out” and saw that I had missed the vernier and maneuvering jets on the hull.

“How are these powered?” I asked Vicki.

“Hydrogen Peroxide, H2O2” she replied.

“Where’s the fuel?”.

“There isn’t any yet. It’s made during the flight. Some of the water in the hull is tapped off, run through that off-the-shelf, standard unit over there. We store the peroxide in hull pockets to wait for the next use. The peroxide engines aren’t very efficient, having an Isp of about 160s, but they provide higher thrust than the main engines and can be used to boost the ship for a faster departure, or land the ship on low gravity worlds with orbital delta-Vs of 0.5 km/s or less. The peroxide has other uses too. It can be decomposed to provide oxygen [3] more quickly than the main ESS electrolyzers, act as an energy store for emergency power [4] and finally as an excellent bactericide to keep the interior clean and remove the bacterial slimes and molds that grow on the inner skin, often in difficult to reach spaces. And before you ask, yes, we have rotating cleaning duties on the Martian Queen.”

So the water in the hull fulfilled a range of uses, before being finally consumed as propellant. Major uses included bathing, direct consumption, rehydrating food, growing plants and, of course, the main oxygen supply. It was converted to peroxide for the high thrust engines, for energy storage and for another emergency O2 supply.

“Vicki, a quick mental calculation seems to come up short on the water requirement for the flight. Is what I see all that is needed?”

Vicki smiled: “The impact of using water as propellant on performance is significant. The total water budget for the trip is about 4 times the total mass of the ship and payload, compared to about 14 times for a conventional liquid hydrogen and LOX chemical rocket, primarily because of the higher Isp of the electrothermal engines. But the low hull mass and reduced consumables payload reduces the main mass of the the Martian Queen allowing a much smaller, more efficient spaceship. She is also a lot roomier, more comfortable and much safer. An Apollo 13 type accident would not be survivable in a conventional ship, but we have very large reserves of consumables and oxygen for the crew to survive until a rescue or the return trajectory was complete. In addition, even without water supplies at Phobos, the baseline mission cost to Phobos and return is on the order of a $100m dollars. That is why your institution can afford to pay for your slot on this mission. Reusability of the Martian Queen for multiple missions, fresh water at Phobos, and better performing solar panels and electric engines will eventually reduce that cost perhaps another order of magnitude.”

I pondered that for a moment. While not a cheap solution for interplanetary travel, it put the cost well within the realm of the super-rich and wealthy institutions. A mere decade earlier, a simple lunar flyby and return in an adapted Soyuz craft was priced at around $100m per passenger by Space Adventures. Spaceflight was definitely getting cheaper and safer.

————————-

If interplanetary travel is initially based around the design concepts of water propellant craft, then the economics and infrastructure requirements will be dependent on available supplies of water already in space at suitable locations for fuel dumps. Bodies that may harbor economically useful quantities of accessible water include the moon (shadowed polar regions), water rich asteroids and dead comets. A tantalizing possibility is Ceres, that Dawn is expected to rendezvous with this year (2015). Ceres is expected to have prodigious quantities of frozen water, possibly even a subsurface ocean. A mining operation to extract pure water from the brew of ice and chemicals might offer the opportunity to open up the inner solar solar system. Once at Jupiter, the icy moons offer an almost inexhaustible supply of water.

References

1. Pykrete http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pykrete

2. Bigelow Aerospace B330 http://bigelowaerospace.com/b330/

3. 47kg O2/1000 kg H2O2 (10%)

4. ~2 MJ, kg.

5. J E Brandenburg, J Kline and D Sullivan, “The microwave electro-thermal (MET) thruster using water vapor propellant,” Plasma Science, IEEE Transactions on (Volume:33, Issue:2) pp 776-782 (2005).

6. E. Wernimont, M. Ventura, G. Garboden and P. Mullens. “Past and Present Uses of Rocket Grade Hydrogen Peroxide”, http://www.hydrogen-peroxide.us/history-US-General-Kinetics/H2O2_Conf_1999-Past_Present_Uses_of_Rocket_Grade_Hydrogen_Peroxide.pdf

Gemini Planet Imager: Early Success at Cerro Pachon

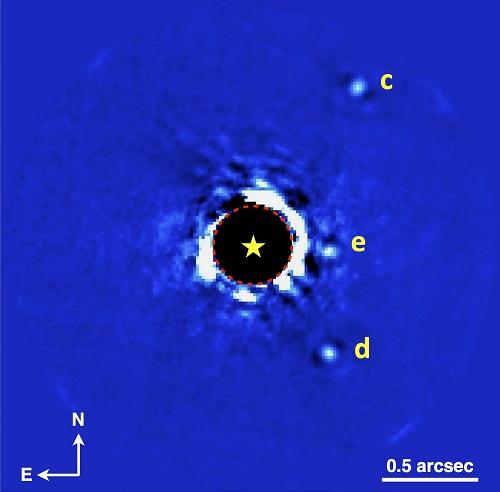

Working at near-infrared wavelengths, the Gemini Planet Imager, now entering regular operations at the Gemini South Telescope in Cerro Pachon (Chile), is producing striking work, including images of exoplanets and circumstellar disks. Have a look at the image below, which highlights the instrument’s ability to achieve high contrast at small angular separations. Such capabilities make it possible to image exoplanets around nearby stars, as seen here in the case of the star HR 8799.

Image: GPI imaging of the planetary system HR 8799 in K band, showing 3 of the 4 planets. (Planet b is outside the field of view shown here, off to the left.) These data were obtained on November 17, 2013 during the first week of operation of GPI and in relatively challenging weather conditions, but with GPI’s advanced adaptive optics system and coronagraph the planets can still be clearly seen and their spectra measured. Credit: Christian Marois (NRC Canada), Patrick Ingraham (Stanford University) and the GPI Team.

This work, presented at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Seattle, is especially promising given that the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI) has until recently been in its commissioning phase, observing a wide range of targets as the instrument was integrated into the Gemini Observatory software. Patrick Ingraham (Stanford University), lead author of the upcoming paper on HR 8799, notes that even these early observations were productive, revealing spectra for two of the planets that differed markedly from what had been expected given their similar colors.

“Current atmospheric models of exoplanets cannot fully explain the subtle differences in color that GPI has revealed,” Ingraham added..”We infer that it may be differences in the coverage of the clouds or their composition. The fact that GPI was able to extract new knowledge from these planets on the first commissioning run in such a short amount of time, and in conditions that it was not even designed to work, is a real testament to how revolutionary GPI will be to the field of exoplanets.”

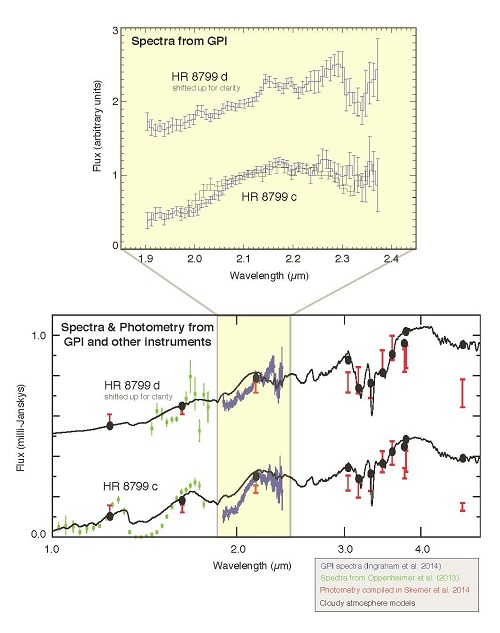

Image: GPI spectroscopy of planets c and d in the HR 8799 system. While earlier work showed that the planets have similar overall brightness and colors, these newly-measured spectra show surprisingly large differences. The spectrum of planet d increases smoothly from 1.9-2.2 microns while planet c’s spectrum shows a sharper kink upwards just beyond 2 microns. These new GPI results indicate that these similar-mass and equal-age planets nonetheless have significant differences in atmospheric properties, for instance more open spaces between patchy cloud cover on planet c versus uniform cloud cover on planet d, or perhaps differences in atmospheric chemistry. These data are helping refine and improve a new generation of atmospheric models to explain these effects. Credit: Patrick Ingraham (Stanford University), Mark Marley (NASA Ames), Didier Saumon (Los Alamos National Laboratory) and the GPI Team.

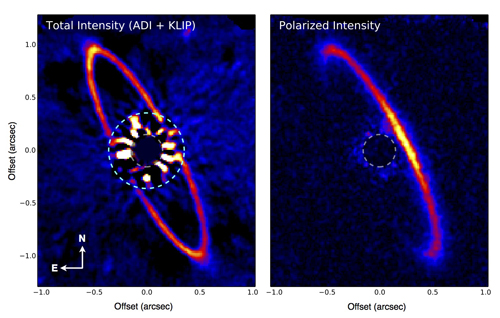

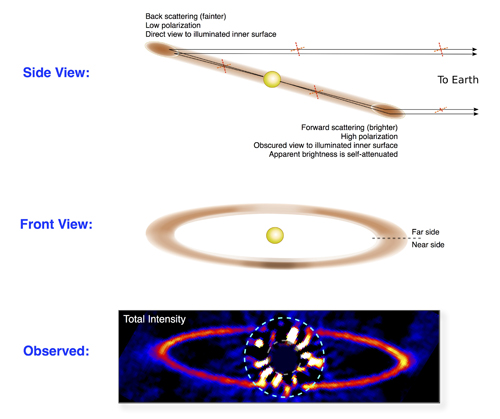

Also revealed at AAS 225 was imagery from the dusty disk around the young star HR 4796A, seen below. Here the striking feature is the instrument’s ability to analyze the polarized light of the disk, which reveals that it must be partially opaque. That would suggest a disk composition much denser than the dust found in the outer regions of our own Solar System. The HR 4796A dust ring is about twice the diameter of the planetary orbits in our system, while its star is twice the mass of the Sun.

Image: GPI imaging polarimetry of the circumstellar disk around HR 4796A, a ring of dust and planetesimals similar in some ways to a scaled up version of the solar system’s Kuiper Belt. These GPI observations reveal a complex pattern of variations in brightness and polarization around the HR 4796A disk. The western side (tilted closer to the Earth) appears brighter in polarized light, while in total intensity the eastern side appears slightly brighter, particularly just to the east of the widest apparent separation points of the disk. Reconciling this complex and apparently-contradictory pattern of brighter and darker regions required a major overhaul of our understanding of this circumstellar disk. Credit: Marshall Perrin (Space Telescope Science Institute), Gaspard Duchene (UC Berkeley), Max Millar-Blanchaer (University of Toronto), and the GPI Team.

The illustration below explains the team’s current thinking on the HR 4796A disk.

Image: Diagram depicting the GPI team’s revised model for the orientation and composition of the HR 4796A ring. To explain the observed polarization levels, the disk must consist of relatively large (> 5 µm) silicate dust particles, which scatter light most strongly and polarize it more for forward scattering. To explain the relative faintness of the east side in total intensity, the disk must be dense enough to be slightly opaque, comparable to Saturn’s optically thick rings, such that on the near side of the disk our view of its brightly illuminated inner portion is partially obscured. This revised model requires the disk to be much narrower and flatter than expected, and poses a new challenge for theories of disk dynamics to explain. GPI’s high contrast imaging and polarimetry capabilities together were essential for this new synthesis. Credit: Marshall Perrin (Space Telescope Science Institute).

The Gemini Planet Imager is now open to proposals for early observations in 2015. The core science program for the instrument is to be the Gemini Planet Imager Exoplanet Survey (GPIES), which will look at 600 young and relatively nearby stars over the next several years. The planets of such stars will offer the best targets for the GPI’s infrared wavelength operations. All told, the GPIES intends to make 890 hours of observations over the next three years. This Gemini Observatory news release offers additional background.

Be aware that Marshall Perrin (Space Telescope Science Institute), who is one of the team leaders on the Gemini Planet Imager (and the scientist who presented these results at the AAS meeting), used to write a highly readable astronomy column for the online science fiction magazine Strange Horizons. It’s been a bit over five years since his last, and I for one would love to see the column resumed. Consider this a gentle nudge in that direction.

Closing on Earth 2.0?

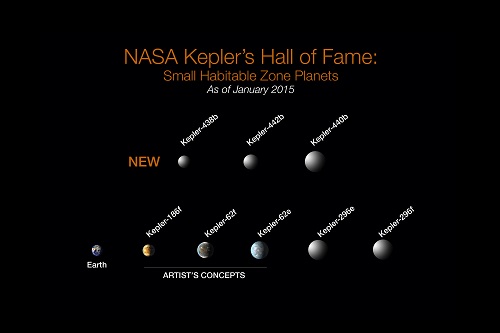

The eight ‘habitable zone’ planets we discussed yesterday appear today in a much broader context. The Kepler mission has verified its 1000th planet, and with the detection of 554 more planet candidates, the total candidate count has now reached 4175. According to this NASA news release, six of the new planet candidates are near-Earth size and orbit in the habitable zone of stars similar to the Sun. These all require follow-up observation to confirm their status as planets, but with confirmed planets like Kepler-438b and Kepler-442b, along with these further candidates in the habitable zone, the numbers keep inching us closer to an Earth 2.0.

“Kepler collected data for four years — long enough that we can now tease out the Earth-size candidates in one Earth-year orbits,” says Fergal Mullally, a SETI Institute Kepler scientist at Ames who led the analysis of a new candidate catalog. “We’re closer than we’ve ever been to finding Earth twins around other sun-like stars. These are the planets we’re looking for.”

The next catalog release of the Kepler data set is now in the works, an analysis that will include the final month of mission data put through a new and more sensitive software iteration, one that should be able to tease out still further signatures of Earth-size planets.

Image: NASA Kepler’s Hall of Fame: Of the more than 1,000 verified planets found by NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope, eight are less than twice Earth-size and in their stars’ habitable zone. All eight orbit stars cooler and smaller than our Sun. The search continues for Earth-size habitable zone worlds around Sun-like stars. Credit: NASA/Kepler team.

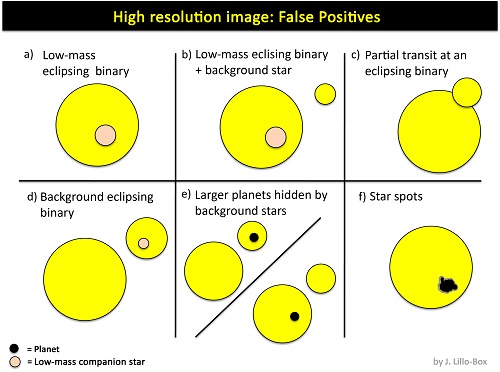

The paper on the recently validated ‘habzone’ planets has now reached arXiv, where you can find the preprint of Torres et al., “Validation of Twelve Small Kepler Transiting Planets in the Habitable Zone.” I want to pull a paragraph out of this paper with regard to the BLENDER analysis I referred to yesterday. BLENDER is a powerful tool using software analysis of false-positive scenarios that is particularly useful when planets are so far away that radial velocity confirmation is difficult. A planetary transit can be mimicked by other phenomena, such as background or foreground eclipsing binary stars, whose light can create a ‘blend’ of signals that has to be untangled. The paper describes how BLENDER can rule false positives out:

BLENDER makes full use of the detailed shape of the transits to limit the pool of viable blends. It does this by simulating large numbers of blend scenarios and comparing each of them with the Kepler photometry in a ?2 sense. Fits that give the wrong shape for the transit are considered to be ruled out. This enables us to place useful constraints on the properties of the objects that make up the blend, including their sizes and masses, overall color and brightness, the linear distance between the background/foreground eclipsing pair and the target, and even the eccentricities of the orbits. Those constraints are then used to estimate the frequencies of blends of different kinds.

Image: False positive scenarios of the kind BLENDER can help resolve. Credit: Calar Alto Observatory/J. Lillo-Box.

BLENDER’s simulated lightcurves, along with other tools like high-resolution spectroscopy, allow tricky catches like Kepler-438b and Kepler-442b to be validated. The process is exhaustive and highlights just how far we’re progressing in our ability to find these small worlds. The paper presents the current state of the art in action, a fascinating and encouraging account that has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

Also apropos of this week of planetary announcements keyed to the American Astronomical Society meeting in Seattle is work that Courtney Dressing (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) presented on Monday. Using the HARPS-North instrument on the 3.6-meter Telescopio Nazionale Galileo in the Canary Islands, Dressing and Harvard astronomer David Charbonneau have been examining the ten known exoplanets with diameter less than 2.7 times that of Earth that have accurately measured masses. The result: The five planets with diameters smaller than 1.6 that of Earth showed a tight relationship between mass and size.

“To find a truly Earth-like world,” says Dressing, “we should focus on planets less than 1.6 times the size of Earth, because those are the rocky worlds.”

In this study, larger and more massive exoplanets showed significantly lower densities, an indication that they include a large amount of water or other volatiles like hydrogen or helium. This CfA news release notes that Dressing and Charbonneau do not believe that all planets less than six times the mass of Earth are necessarily rocky — planets like those in the Kepler-11 system show both low mass and low density. But the assumption here is that the average low-mass planet orbiting near its star has a high chance of having a rocky composition like the Earth.

The paper on this work, which has been accepted for publication at The Astrophysical Journal, isn’t yet up on arXiv, but I’ll publish the reference when it becomes available. Meanwhile, the paper by Laura Schaefer and Dimitar Sasselov on ‘super-Earth’ oceans, examined here on Monday, has now appeared. It’s “The persistence of oceans on Earth-like planets: insights from the deep-water cycle,” likewise accepted for publication at The Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

AAS: 8 New Planets in Habitable Zone

One way to confirm the existence of a transiting planet is to run a radial velocity check to see if it shows up there as a gravitationally induced ‘wobble’ in the host star. But in many cases, the parent stars are too far away to allow accurate measurements of the planet’s mass. What Guillermo Torres (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) did in the case of eight new candidates possibly in their stars’ habitable zones was to use BLENDER, a software program he and Francois Fressin developed that runs at NASA Ames on the Pleiades supercomputer.

A BLENDER analysis can determine whether candidates are statistically likely to be planets. Torres and Fressin have applied it before in the case of small worlds like Kepler 20e and Kepler 20f, important finds because both were exoplanets near the size of the Earth. Using the software allowed the researchers to create a range of false-positive scenarios to see which could reproduce the observed signal. A nearby binary star system, for example, could cause a dimming of the star’s light that might be mistaken for a planet. The Pleiades supercomputer allowed the team to work through almost a billion different scenarios, which in the case of Kepler 20e showed that it was 3,400 times more likely to be a planet than a false positive.

Applying the same techniques to the eight new planet candidates, Torres and team went on to spend a year doing follow-up work in adaptive optics imaging, high-resolution spectroscopy and speckle interferometry to characterize the new systems. We learn from all this that all eight of these worlds meet the team’s standards for verifiability. All orbit at a distance where liquid water could occur on their surfaces, while two are, as researchers told a meeting of the American Astronomical Society today, more similar to Earth than any exoplanets we’ve yet found.

The similarity in question refers to the size and composition of the two planets rather than other broad characteristics like the star they orbit. Unlike our G-class star, the primary star for Kepler-438b is a red dwarf, while Kepler-442b orbits a K-class star. Kepler-438b receives about 40 percent more light than Earth (Venus receives twice the solar flux of Earth), while Kepler 442b gets about two-thirds the light of Earth. The team gives the latter a 97 percent chance of being in the habitable zone, while the former’s chances are calculated at 70 percent.

Image: This artist’s conception depicts an Earth-like planet orbiting an evolved star that has formed a stunning “planetary nebula.” Earlier in its life, this planet may have been like one of the eight newly discovered worlds orbiting in the habitable zones of their stars. Credit: David A. Aguilar (CfA).

Kepler-438b, 470 light years from Earth, is in a 35-day orbit, while Kepler 442b (1100 light years away) completes an orbit around its star every 112 days. Four of the eight newly found planets are in multiple-star systems, although in each case, according to this CfA news release, the companion stars are far enough away not to exert a significant influence on the observed planets.

A key question is whether these really are rocky worlds — without a measurement of planetary mass, their composition is unknown. Torres and colleagues think that Kepler-438b, with a diameter about 12 percent larger than Earth, has a 70 percent chance of being rocky. Kepler 442b is about a third larger than Earth, but by the team’s reckoning has a 60 percent chance of being rocky. So these are intriguing possibilities, but it has to be said that habitability remains no more than an inference. “We don’t know for sure whether any of the planets in our sample are truly habitable,” says second author David Kipping (CfA). “All we can say is that they’re promising candidates.”

Oceans on a Larger ‘Earth’

We often think about how thin Earth’s atmosphere is, imagining our planet as an apple, with the atmosphere no thicker than the skin of the fruit. That vast blue sky can seem all but infinite, but the great bulk of it is within sixteen kilometers of the surface, always thinning as we climb toward space. Now a presentation by graduate student Laura Schaefer (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) at the 225th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle points out that, like the atmosphere, water is also a tiny fraction of what makes up our planet.

A small enough fraction, in fact, that although water does cover seventy percent of the Earth’s surface, it makes up only about a tenth of one percent of the overall bulk of a world that is predominantly rock and iron. Dimitar Sasselov (CfA), co-author of the paper on this work, thinks of Earth’s oceans as a film as thin as fog on a bathroom mirror. But we’ve seen recently that water isn’t strictly a surface phenomenon. The Earth’s mantle, in fact, holds several oceans of water pulled underground by plate tectonics and subduction of the ocean seafloor.

What Schaefer presented at the AAS is a report on her computer simulations of the planet-wide recycling that keeps Earth’s oceans from disappearing. Volcanic outgassing from the mantle, primarily at the mid-ocean ridges, keeps water returning to the surface even as subduction returns water to the mantle. The cycle maintains the oceans over aeons. The question for the researchers was whether similar cycles occur on super-Earths, and how long it would take an ocean to form after the cooling of a planet’s crust during its formation period.

The results are encouraging for those hoping to find stable oceans on super-Earths. Planets two to four times Earth’s mass turn out to be better at maintaining their oceans than Earth itself. Super-Earth oceans can persist for ten billion years unless destroyed by a red giant primary star as it nears the end of its life. The largest planet in these simulations — five times Earth’s mass — took a billion years to develop its ocean in the first place, however, the result of a thicker crust and lithosphere and the resultant delay in volcanic outgassing.

Image: This artist’s depiction shows a gas giant planet rising over the horizon of an alien waterworld. New research shows that oceans on super-Earths, once established, can last for billions of years. Credit: David A. Aguilar (CfA).

We have nothing to compare the timeframe of life’s development on Earth with, having no data on life elsewhere. But if we took our model as the norm, says this CfA news release, we would be wise to look for life on older super-Earths, those perhaps a billion years older than the Earth, given the lag time in getting those oceans into play. Sasselov notes:

“It takes time to develop the chemical processes for life on a global scale, and time for life to change a planet’s atmosphere. So, it takes time for life to become detectable.”

My own guess is that once we do develop the ability to study exoplanet atmospheres on the level of Earth-sized worlds, we’ll run into surprises on this front as well, depending on how typical the experience of getting life started on Earth really was. In any case, screening for older planets as the best targets for complex life seems like a rational procedure, but especially with super-Earths for whom surface water may be a slow-developing resource.

The paper is Schaefer and Sasselov, “Persistence of oceans on Earth-like planets,” American Astronomical Society, AAS Meeting #225, #406.04 (abstract).

Stars Passing Close to the Sun

Every time I mention stellar distances I’m forced to remind myself that the cosmos is anything but static. Barnard’s Star, for instance, is roughly six light years away, a red dwarf that was the target of the original Daedalus starship designers back in the 1970s. But that distance is changing. If we were a species with a longer lifetime, we could wait about eight thousand years, at which time Barnard’s Star would close to less than four light years. No star shows a larger proper motion relative to the Solar System than this one, which is approaching at about 140 kilometers per second.

The Alpha Centauri stars are the touchstone for close mission targets, but here again we could make our journey shorter with a little patience. In 28,000 years, having moved into the constellation Hydra, these stars will have closed to less than 3 light years from the Sun. Some time back, Erik Anderson discussed star motion in his highly readable Vistas of Many Worlds (Ashland Astronomy Studio, 2012), where I learned that the star Gliese 710, currently 64 light years out in the constellation Serpens, is headed squarely in our direction. Wait around for 1.3 million years or so and Gl 710 will push right through the Oort Cloud, with who knows what results in the inner system. A new paper considers these matters and tunes up the numbers on stellar encounters.

Image: Could a passing star dislodge comets from otherwise stable orbits so that they enter the inner system? Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech).

A close pass from a star is bound to cause effects elsewhere in the Solar System, as Coryn Bailer-Jones (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg) notes in his latest paper. Such an encounter can disrupt cometary orbits in the Oort, sending them into the inner system. Earth’s catalog of impact craters, which contains almost 200 known craters and doubtless should include many awaiting discovery, some of them beneath the oceans, is a reminder of what can happen. Nor should we forget that if we really drew the wild card, a close star turning supernova could have disastrous effects on surface life. So how many stars are problematic?

Bailer-Jones identifies the key candidates in this paper, assuming an Oort Cloud that extends to about 0.5 parsecs (1.6 light years), but he notes that a star passing even as close as several parsecs could produce significant cometary disruptions if the star were massive and slow enough. The author worked with 50,000 stars from the Hipparcos astrometric catalog in hopes of fine-tuning earlier studies of passing stars, but he notes that the search can’t be considered complete because radial velocities are not available for all stars and many are fainter than the Hipparcos work could detect. Further analysis will be needed using upcoming Gaia data.

But studying stars within a few tens of light years from the Solar System, Bailer-Jones finds forty that at some point were or will be within 6.4 light years of the Sun — the timeframe here extends from 20 million years in the past to 20 million years in the future. Fourteen stars, in fact, come within 3 light years of the Sun, with the closest encounter being with HIP 85605, which is currently about 16 light years away in the constellation of Hercules. The paper cites “…a 90% probability of [the star] coming between 0.04 and 0.20 pc” somewhere between 240,000 and 470,000 years from now, but Bailer Jones notes that this encounter has to be treated with caution because the astrometry may be incorrect. Future Gaia data should resolve this.

If HIP 85605 were to close to 0.04 parsecs of the Sun, it would be .13 light years out, or roughly 8200 AU, a close pass indeed. But one thing to keep in mind: Oort Cloud perturbation is not an unusual phenomenon, and the situation we are dealing with today is partially the result of encounters with stars that have occurred in the past. We have no data on the time between stellar encounters like these and the subsequent entry of comets into the inner system, making it all but impossible to link a specific passing star with a rise in the rate of Earth impacts. Bailer-Jones discusses all this on his website at the MPIA, where he notes the following:

A close encountering star is likely to perturb the Oort cloud sufficiently to increase the flux of comets entering the inner solar system. Let’s not forget, however, that this kind of perturbation is happening all the time due to the gravitational effect of the Galaxy as whole, and due to stars which [were] encountered even earlier. That is, there is a “background” of comets entering the inner solar system which we cannot necessarily associate with a particular stellar encounter. This is also because the time between an encounter and the time that comets enter the inner solar system could be many or even many tens of millions of years, much longer that than the typical time between close encounters.

Gl 710 is generally cited as the star making the closest encounter in previous studies, and Bailer-Jones sees a 90 percent probability that it passes within 0.10 to 0.44 parsecs, meaning an Oort Cloud passage in 1.3 million years. Looking into the past, the star gamma Microscopii, a G6 giant, encountered the Sun 3.8 million years ago, probably the most massive encounter within one parsec or less. Some encounters are recent: Tiny Van Maanen’s star, a white dwarf, passed near our Sun as recently as 15,000 years ago. While data from the Gaia mission will help us improve the parameters of this catalog of passing stars, Bailer-Jones believes the Gaia results will also make it possible to investigate the link between stellar encounters and impacts in a broad, statistical sense, helping us better understand the history of Earth impacts.

The paper is Bailer-Jones, “Close Encounters of the Stellar Kind,” accepted at Astronomy & Astrophysics (preprint).