Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Beamed Sails: The Problem with Lasers

We saw on Friday through Jim Benford’s work that pushing a large sail with a neutral particle beam is a promising way to get around the Solar System, although it presents difficulties for interstellar work. Benford was analyzing an earlier paper by Alan Mole, which had in turn drawn on issues Dana Andrews raised about beamed sails. Benford saw that the trick is to keep a neutral particle beam from diverging so that the spot size of the beam quickly becomes much larger than the diameter of the sail. By his calculations, only a fraction of the particle beam Mole envisaged would actually strike the sail, and even laser cooling methods were ineffective at preventing this.

It seems a good time to look back at Geoffrey Landis’ paper on particle beam propulsion. I’m hoping to discuss some of these ideas with him at the upcoming Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop sessions in Oak Ridge, given that Jim Benford will also be there. The paper is “Interstellar Flight by Particle Beam” (citation below), published in 2004 in Acta Astronautica, a key reference in an area that has not been widely studied. In fact, the work of Mole, Andrews and Benford, along with Landis and Gerald Nordley, is actively refining particle beam propulsion concepts, and what I’m hoping to do here is to get this work into a broader context.

Image: Physicist and science fiction writer Geoffrey Landis (Glenn Research Center), whose ideas on particle beam propulsion have helped bring the idea into greater scrutiny.

Particle beams are appealing because they solve many of the evident limitations of laser beaming methods. To understand these problems, let’s look at their background. The man most associated with the development of the laser sail concept is Robert Forward. Working at the Hughes Aircraft Company and using a Hughes fellowship to assist his quest for degrees in engineering (at UCLA) and then physics (University of Maryland), Forward became aware of Theodore Maiman’s work on lasers at Hughes Research Laboratories. The prospect filled him with enthusiasm, as he wrote in an unfinished autobiographical essay near the end of his life:

“I knew a lot about solar sails, and how, if you shine sunlight on them, the sunlight will push on the sail and make it go faster. Normal sunlight spreads out with distance, so after the solar sail has reached Jupiter, the sunlight is too weak to push well anymore. But if you can turn the sunlight into laser light, the laser beam will not spread. You can send on the laser light, and ride the laser beam all the way to the stars!”

The idea of a laser sail was a natural. Forward wrote it up as an internal memo within Hughes in 1961 and published it in a 1962 article in Missiles and Rockets that was later reprinted in Galaxy Science Fiction. George Marx picked up on Forward’s concepts and studied laser-driven sails in a 1966 paper in Nature. Remember that Forward’s love of physical possibility was accompanied by an almost whimsical attitude toward the kind of engineering that would be needed to make his projects possible. But the constraints are there, and they’re formidable.

Landis, in fact, finds three liabilities for beamed laser propulsion:

- The energy efficiency of a laser-beamed lightsail infrastructure is extremely low. Landis notes that the force produced by reflecting a light beam is no more than 6:7 N/GW, and that means that you need epically large sources of power, ranging in some of Forward’s designs all the way up to 7.2 TW. We would have to imagine power stations built and operated in an inner system orbit that would produce the energy needed to drive these mammoth lasers.

- Because light diffracts over interstellar distances, even a laser has to be focused through a large lens to keep the beam on the sail without wasteful loss. In Forward’s smaller missions, this involved lenses hundreds of kilometers in diameter, and as much as a thousand kilometers in diameter for the proposed manned mission to Epsilon Eridani with return capability. This seems highly impractical in the near term, though as I’ve noted before, it may be that a sufficiently developed nanotechnology mining local materials could construct large apertures like this. The time frame for this kind of capability is obviously unclear.

- Finally, Landis saw that a laser-pushed sail would demand ultra-thin films that would need to be manufactured in space. The sail has to be as light as possible given its large size because we have to keep the mass low to achieve the highest possible mission velocities. Moreover, that low mass requires that we do away with any polymer substrate so that the sail is made only of an extremely thin metal or dielectric reflecting layer, something that cannot be folded for deployment, but must be manufactured in space. We’re a long way from these technologies.

This is why the particle beam interests Landis, who also looked at the concept in a 1989 paper, and why Dana Andrews was drawn to do a cost analysis of the idea that fed into Alan Mole’s paper. Gerald Nordley also discussed the use of relativistic particle beams in a 1993 paper in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. Here is Landis’ description of the idea as of 2004:

In this propulsion system, a charged particle beam is accelerated, focused, and directed at the target; the charge is then neutralized to avoid beam expansion due to electrostatic repulsion. The particles are then re-ionized at the target and reflected by a magnetic sail, resulting in a net momentum transfer to the sail equal to twice the momentum of the beam. This magnetic sail was originally proposed to be in the form of a large superconducting loop with a diameter of many tens of kilometers, or “magsail” [7].

The reference at the end of the quotation is to a paper by Dana Andrews and Robert Zubrin discussing magnetic sails and their application to interstellar flight, a paper in which we learn that some of the limitations of Robert Bussard’s interstellar ramjet concept — especially drag, which may invalidate the concept because of the effects of the huge ramscoop field — could be turned around and used to our advantage, either for propulsion or for braking while entering a destination solar system. Tomorrow I’ll continue with this look at the Landis paper with Jim Benford’s findings on beam divergence in mind as the critical limiting factor for the technology.

The Landis paper is “Interstellar flight by particle beam,” Acta Astronautica 55 (2004), 931-934. The Dana Andrews paper is “Cost considerations for interstellar missions,” Paper IAA-93-706, 1993. Gerald Nordley’s 1993 paper is “Relativistic particle beams for interstellar propulsion,” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society 46 (1993) 145-150.

Sails Driven by Diverging Neutral Particle Beams

Is it possible to use a particle beam to push a sail to interstellar velocities? Back in the spring I looked at aerospace engineer Alan Mole’s ideas on the subject (see Interstellar Probe: The 1 KG Mission and the posts immediately following). Mole had described a one-kilogram interstellar payload delivered by particle beam in a paper in JBIS, and told Centauri Dreams that he was looking for an expert to produce cost estimates for the necessary beam generator. Jim Benford, CEO of Microwave Sciences, took up the challenge, with results that call interstellar missions into doubt while highlighting what may become a robust interplanetary technology. Benford’s analysis, to be submitted in somewhat different form to JBIS, follows.

by James Benford

Alan Mole and Dana Andrews have described light interstellar probes accelerated by a neutral particle beam. I’ve looked into whether that particle beam can be generated with the required properties. I find that unavoidable beam divergence, caused by the neutralization process, makes the beam spot size much larger than the sail diameter. While the neutral beam driven method can’t reach interstellar speeds, fast interplanetary missions are more credible, enabling fast travel of small payloads around the Solar System.

Neutral-Particle-Beam-Driven Sail

Dana Andrews proposed propulsion of an interstellar probe by a neutral particle beam and Alan Mole later proposed using it to propel a lightweight probe of 1 kg [1,2] The probe is accelerated to 0.1 c at 1,000 g by a neutral particle beam of power 300 GW, with 16 kA current, 18.8 MeV per particle. The particle beam intercepts a spacecraft that is a magsail: payload and structure encircled by a magnetic loop. The loop magnetic field deflects the particle beam around it, imparting momentum to the sail, and it accelerates.

Intense particle beams have been studied for 50 years. One of the key features is that the intense electric and magnetic fields required to generate such beams determine many features of the beam and whether it can propagate at all. For example, intense charged beams injected into a vacuum would explode. Intense magnetic fields can make beam particles ‘pinch’ toward the axis and even reverse their trajectories and go backwards. Managing these intense fields is a great deal of the art of using intense beams.

In particular, a key feature of such intense beams is the transverse velocity of beam particles. Even though the bulk of the energy propagates in the axial direction, there are always transverse motions caused by the means of generation of beams. For example, most beams are created in a diode and the self-fields in that diode produce some transverse energy. Therefore one cannot simply assume that there is a divergence-less beam.

What I will deal with here is how small that transverse energy can be made to be. The reason this is important for the application is that the beam must propagate over the large distances, to accelerate the probe to 0.3 AU or 45,000,000 km. That requires that the beam divergence be very small. In the original paper on the subject by Dana Andrews (2), the beam divergence is simply stated to be 3 nanoradians. This very small divergence was simply assumed, because without it the beam will spread much too far and so the beam energy will not be coupled to the magsail. (Note that at 0.3 AU, this divergence results in a 270 m beam cross-section, about the size of the magsail capture area.)

Just what are a microradian and nanoradian? A beam from Earth to the moon with microradian divergence would hit the moon with a spot size of about 400 m. For a nanoradian it would be a very small 0.4 m, which is about 15 inches.

One method of getting a neutral particle beam might be to generate separate ion and electron beams and combine them. But two nearby charged beams would need to be propagated on magnetic field lines or they would simply explode due to the electrostatic force. If they are propagating parallel to each other along magnetic field lines, they will interact through their currents as well as their charges. The two beams will experience a JxB force, which causes them to spiral about each other. This produces substantial transverse motion before they merge. This example shows why the intense fields of particle beams create beam divergence no matter how carefully one can design them. But what about divergence of neutral particle beams?

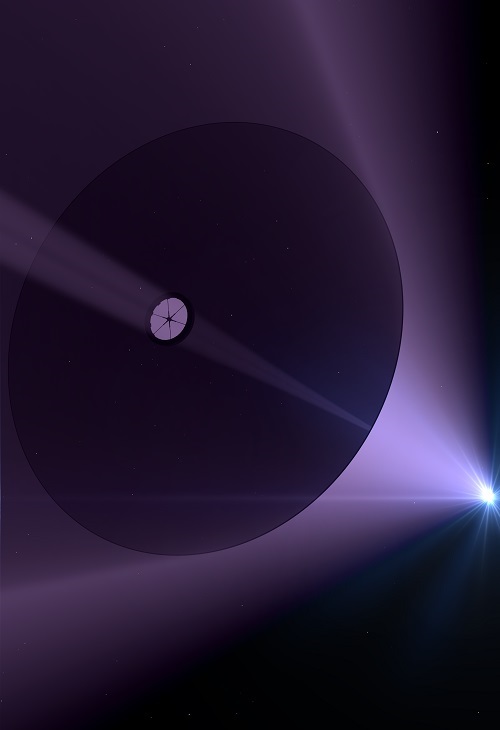

Image: A beamed sail mission as visualized by the artist Adrian Mann.

Neutral Beam Divergence

The divergence angle of a neutral beam is determined by three factors. First, the acceleration process can give the ions a slight transverse motion as well as propelling them forward. Second, focusing magnets bend low-energy ions more than high-energy ions, so slight differences in energy among the accelerated ions lead to divergence (unless compensated by more complicated bending systems).

Third, and quite fundamentally, the divergence angle introduced by stripping electrons from a beam of negative hydrogen or tritium ions to produce a neutral beam gives the atom a sideways motion. (To produce a neutral hydrogen beam, negative hydrogen atoms with an extra electron are accelerated; the extra electron is removed as the beam emerges from the accelerator.)

Although the first two causes of divergence can in principle be reduced, the last source of divergence is unavoidable.

In calculations I will submit to JBIS, the divergence angle introduced by stripping electrons from a beam of negative ions to produce a neutral beam, giving the resulting atom a sideways motion, produces a fundamental divergence. It’s a product of two ratios, both of them small: a ratio of particle masses (?10-3) and a ratio of neutralization energy to beam particle energy (?10-7 for interstellar missions). Divergence is small, typically 10 microradians, but far larger than the nanoradians assumed by Andrews and Mole. Furthermore, the divergence is equal to the square root of the two ratios, making it insensitive to changes in ion mass and ionization energy.

In Alan Mole’s example, the beam velocity is highest at the end of acceleration, 0.2 c, twice the ship final velocity. Particle energy for neutral hydrogen is 18.8 MeV. The energy imparted to the electron to drive it out of the beam, resulting in a neutral, is 0.7 eV for hydrogen. Evaluation of Eq. 3 gives beam divergence of 4.5 microradians.

This agrees with experimental data from the Strategic Defense Initiative, SDI. The observed divergence of a 100 MeV neutral beam as 3.6 microradians; for a Triton beam (atomic weight 3), 2 microradians.

The beam size at the end of acceleration will be 411 km. Alan Mole’s magnetic hoop is 270 m in diameter. Therefore the ratio of the area of the beam to the area of the sail is 2.3 106. Only a small fraction of the beam impinges on the spacecraft. To reduce the beam divergence, one could use heavier particles but no nucleus is heavy enough to reduce the beam spot size to the sail diameter.

Laser Cooling of Divergence?

Gerry Nordley has suggested that neutral particle divergence could be reduced by use of laser cooling. This method uses lasers that produce narrowband photons to selectively reduce the transverse velocity component of an atom, so must be precisely tunable. It is typically used in low temperature molecular trapping experiments. The lasers would inject transversely to the beam to reduce divergence. This cooling apparatus would be located right after the beam is cleaned up as it comes out of the injector. They would have substantial powers in order to neutralize the beam as it comes past at a fraction of the speed of light. Consequently, the coupling between the laser beam and the neutral beam is extraordinarily poor, about 10-5 of the laser beam. This highly inefficient means of limiting divergence is impractical.

Fast Interplanetary Sailing

Beam divergence limits the possibilities for acceleration to interstellar speeds, but fast interplanetary missions look credible using the neutral beam/magsail concept. That enables fast transit to the planets.

Given that the beam divergence is fundamentally limited to microradians, I used that constraint to make rough examples of missions. A neutral beam accelerates a sail, after which it coasts to its target, where a similar system decelerates it to its final destination. Typically the accelerator would be in high Earth orbit, perhaps at a Lagrange point. The decelerating system is in a similar location about another planet such as Mars or Saturn.

From the equations of motion, To get a feeling for the quantities, here are the parameters of missions with sail probes with microradian divergence and increasing acceleration, driven by increasingly powerful beams.

| Beam/Sail Parameters | Fast Interplanetary | Faster Interplanetary | Interstellar Precursor |

|---|---|---|---|

| θ | 1 microradian | 1 microradian | 1 microradian |

| acceleration | 100 m/sec2 | 1000 m/sec2 | 10,000 m/sec2 |

| Ds | 270 m | 270 m | 540 m |

| V0 | 163 km/sec | 515 km/sec | 2,300 km/sec |

| R | 135,000 km | 135,000 km | 270,000 km |

| t0 | 27 minutes | 9 minutes | 4 minutes |

| mass | 3,000 kg | 3,000 kg | 3,000 kg |

| EK | 4 1013 J | 4 1014 J | 8 1015 J |

| P | 24 GW | 780 GW | 34 TW |

| particle energy | 50 MeV | 50 MeV | 50 MeV |

| beam current | 490 A | 15 kA | 676 kA |

| time to Mars | 8.7 days | 34 hours | 8 hours |

The first column shows a fast interplanetary probe, with high interplanetary-scale velocity, acceleration 100 m/sec2, 10 gees, which a nonhuman cargo can sustain. Time required to reach this velocity is 27 minutes, at which time the sail has flown to 135,000 km. The power required for the accelerator is 24GW. If the particle energy is 50MeV, well within state-of-the-art, then the required current is 490A. How long would an interplanetary trip take? If we take the average distance to Mars as 1.5 AU, the probe will be there in 8.7 days. Therefore this qualifies as a Mars Fast Track accelerator.

An advanced probe, at 100 gees acceleration, requires 0.78 TW power and the current is 15 kA. It takes only 34 hours to reach Mars. At such speeds the outer solar system is accessible in a matter of weeks. For example, Saturn can be reached by a direct ascent in the time as short as 43 days.

A very advanced probe, an Interstellar Precursor, at 1000 gees acceleration, reaches 0.8% of light speed. It has a power requirement 34 TW and the current is 676 kA. It takes only 8 hours to reach Mars. At such speeds the outer solar system is accessible in a matter of days. For example, Saturn can be reached by a direct ascent in the time as short as a day. The Oort Cloud at 2,000 AU, can be reached in 6 years.

Implications

The rough concepts that have been developed by Andrews, Mole and myself show that neutral beam-driven magnetic sails deserve more attention. But the simple mission scenarios described in the literature to date don’t come to grips with many of the realities. In particular, the efficiency of momentum transfer to the sail should be modeled accurately. Credible concepts for the construction of the sail itself, and especially including the mass of the superconducting hoop, should be assembled. As addressed above, concepts for using laser cooling to reduce divergence are not promising but should be looked into further.

A key missing element is that there is no conceptual design for the beam generator itself. Neutral beam generators thus far have been charged particle beam generators with a last stage for neutralization of the charge. As I have shown, this neutralization process produces a fundamentally limiting divergence.

Neutral particle beam generators so far have been operated in pulsed mode of at most a microsecond with pulse power equipment at high voltage. Going to continuous beams, which would be necessary for the minutes of beam operation that are required as a minimum for useful missions, would require rethinking the construction and operation of the generator. The average power requirement is quite high, and any adequate cost estimate would have to include substantial prime power and pulsed power (voltage multiplication) equipment, a major cost item in the system. It will vastly exceed the cost of the magnetic sails.

The Fast Interplanetary example in table 1 requires 24 GW power for 27 minutes, which is an energy of 11 MW-hours. This is within today’s capability. The Three Gorges dam produces 225 GW, giving 92 TWhr. The other two examples cannot be powered directly off the grid today. So the energy would be stored prior to launch, and such storage, perhaps in superconducting magnets, would be massive.

Furthermore, if it were to be space-based the heavy mass of the high average power required would mean a substantial mass System in orbit. The concept needs economic analysis to see what the cost optimum would actually be. Such analysis would take into account the economies of scale of a large system as well as the cost to launch into space.

We can see that there is in Table 1 an implied development path: a System starts with lower speed, lower mass sails for faster missions in the inner solar system. The neutral beam driver grows as technology improves. Economies of scale lead to faster missions with larger payloads. As interplanetary commerce begins to develop, these factors can be very important to making commerce operate efficiently, counteracting the long transit times between the planets and asteroids. The System evolves.

We’re now talking about matters in the 22nd and 23rd centuries. On this time scale, neutral beam-driven sails can address interstellar precursor missions and interstellar itself from the standpoint of a much more advanced beam divergence technology than we have today.

References

Alan Mole, “One Kilogram Interstellar Colony Mission”, JBIS, 66, pp.381-387, 2013

Dana Andrews, “Cost Considerations for Interstellar Missions”, Acta Astronautica, 34, pp. 357-365, 1994.

Ashton Carter, Directed Energy Missile Defense in Space–A Background Paper, Office of Technology Assessment, OTA-BP-ISC-26, 1984.

G. A. Landis, “Interstellar Flight by Particle Beam”, Acta Astronautica, 55, pp. 931-934, 2004.

G. Nordley, “Jupiter Station Transport By Particle Beam Propulsion”, NASA/OAC, 1994. And http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laser_cooling.

Mapping the Interstellar Medium

The recent news that the Stardust probe returned particles that may prove to be interstellar in origin is exciting because it would represent our first chance to study such materials. But Stardust also reminds us how little we know about the interstellar medium, the space beyond our Solar System’s heliosphere through which a true interstellar probe would one day travel. Another angle into the interstellar medium is being provided by new maps of what may prove to be large, complex molecules, maps that will help us understand their distribution in the galaxy.

The heart of the new work, reported by a team of 23 scientists in the August 15 issue of Science, is a dataset collected over ten years by the Radial Velocity Experiment (RAVE). Working with the light of up to 150 stars at a time, the project used the UK Schmidt Telescope in Australia to collect spectroscopic information about them. The resulting maps eventually drew on data from 500,000 stars, allowing researchers to determine the distances of the complex molecules flagged by the absorption of their light in the interstellar medium.

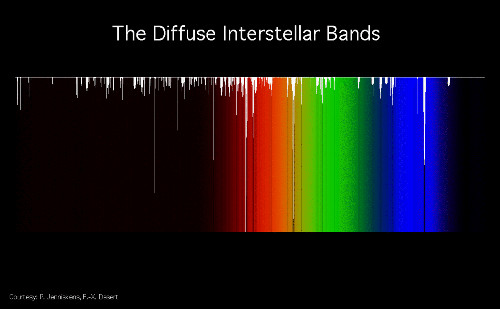

About 400 of the spectroscopic features referred to as ‘diffuse interstellar bands’ (DIBs) — these are absorption lines that show up in the visual and near-infrared spectra of stars — have been identified. They appear to be caused by unusually large, complex molecules, but no proof has existed as to their composition, and they’ve represented an ongoing problem in astronomical spectroscopy since 1922, when they were first observed by Mary Lea Heger. Because objects with widely different radial velocities showed absorption bands that were not affected by Doppler shifting, it became clear that the absorption was not associated with the objects themselves.

That pointed to an interstellar origin for features that are much broader than the absorption lines in stellar spectra. We need to learn more about their cause because the physical conditions and chemistry between the stars are clues to how stars and galaxies formed in the first place. Says Rosemary Wyse (Johns Hopkins), one of the researchers on the project:

“There’s an old saying that ‘We are all stardust,’ since all chemical elements heavier than helium are produced in stars. But we still don’t know why stars form where they do. This study is giving us new clues about the interstellar medium out of which the stars form.”

Image courtesy of Petrus Jenniskens and François-Xavier Désert. See reference below.

But the paper makes clear how little we know about the origins of the diffuse interstellar bands:

Their origin and chemistry are thus unknown, a unique situation given the distinctive family of many absorption lines within a limited spectral range. Like most molecules in the ISM [interstellar medium] that have an interlaced chemistry, DIBs may play an important role in the life-cycle of the ISM species and are the last step to fully understanding the basic components of the ISM. The problem of their identity is more intriguing given the possibility that the DIB carriers are organic molecules. DIBs remain a puzzle for astronomers studying the ISM, physicists interested in molecular spectra, and chemists studying possible carriers in the laboratories.

The researchers have begun the mapping process by producing a map showing the strength of one diffuse interstellar band at 8620 Angstroms, covering the nearest 3 kiloparsecs from the Sun. Further maps assembled from the RAVE data should provide information on the distances of the material causing a wider range of DIBs, helping us understand how it is distributed in the galaxy. What stands out in the work so far is that the complex molecules assumed to be responsible for these dark bands are distributed differently from the dust particles that RAVE also maps. The paper notes two options for explaining this:

…either the DIB carriers migrate to their observed distances from the Galactic plane, or they are created at these large distances, from components of the ISM having a similar distribution. The latter is simpler to discuss, as it does not require knowledge of the chemistry of the DIB carrier or processes in which the carriers are involved. [Khoperskov and Shchekinov] showed that mechanisms responsible for dust migration to high altitudes above the Galactic plane segregate small dust particles from large ones, so the small ones form a thicker disk. This is also consistent with the observations of the extinction and reddening at high Galactic latitudes.

Working with just one DIB, we are only beginning the necessary study, but the current paper presents the techniques needed to map other diffuse bands that future surveys will assemble.

The paper is Kos et al., “Pseudo-three-dimensional maps of the diffuse interstellar band at 862 nm,” Science Vol. 345, No. 6198 (15 August 2014), pp. 791-795 (abstract / preprint). See also Jenniskens and Désert, “Complex Structure in Two Diffuse Interstellar Bands,” Astronomy & Astrophysics 274 (1993), 465-477 (full text).

To Build the Ultimate Telescope

In interstellar terms, a ‘fast’ mission is one that is measured in decades rather than millennia. Say for the sake of argument that we achieve this capability some time within the next 200 years. Can you imagine where we’ll be in terms of telescope technology by that time? It’s an intriguing question, because telescopes capable of not just imaging exoplanets but seeing them in great detail would allow us to choose our destinations wisely even while giving us voluminous data on the myriad worlds we choose not to visit. Will they also reduce our urge to make the trip?

Former NASA administrator Dan Goldin described the effects of a telescope something like this back in 1999 at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society. Although he didn’t have a specific telescope technology in mind, he was sure that by the mid-point of the 21st Century, we would be seeing exoplanets up close, an educational opportunity unlike any ever offered. Goldin’s classroom of this future era is one I’d like to visit, if his description is anywhere near the truth:

“When you look on the walls, you see a dozen maps detailing the features of Earth-like planets orbiting neighboring stars. Schoolchildren can study the geography, oceans, and continents of other planets and imagine their exotic environments, just as we studied the Earth and wondered about exotic sounding places like Banghok and Istanbul … or, in my case growing up in the Bronx, exotic far-away places like Brooklyn.”

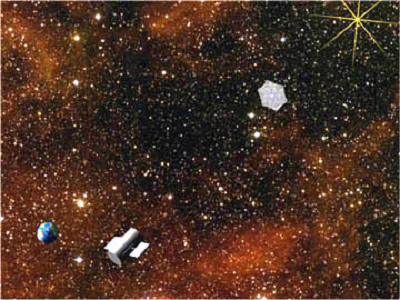

Webster Cash, an astronomer whose Aragoscope concept recently won a Phase I award from the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts program (see ‘Aragoscope’ Offers High Resolution Optics in Space), has also been deeply involved in starshades, in which a large occulter works with a telescope-bearing spacecraft tens of thousands of kilometers away. With the occulter blocking light from the parent star, direct imaging of exoplanets down to Earth size and below becomes possible, allowing us to make spectroscopic analyses of their atmospheres. Pool data from fifty such systems using interferometry and spectacular close-up images may one day be possible.

Image: The basic occulter concept, with telescope trailing the occulter and using it to separate planet light from the light of the parent star. Credit: Webster Cash.

Have a look at Cash’s New Worlds pages at the University of Colorado for more. And imagine what we might do with the ability to look at an exoplanet through a view as close as a hundred kilometers, studying its oceans and continents, its weather systems, the patterns of its vegetation and, who knows, its city lights. Our one limitation would be the orbital inclination of the planet, which would prevent us from mapping every area on the surface, but given the benefits, this seems like a small issue. We would have achieved what Dan Goldin described.

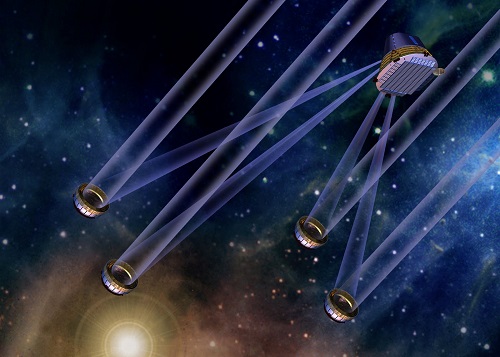

Seth Shostak, whose ideas we looked at yesterday in the context of SETI and political will, has also recently written on what large — maybe I should say ‘extreme’ — telescopes can do for us. In Forget Space Travel: Build This Telescope, which ran in the Huffington Post, Shostak talks about a telescope that could map exoplanets with the same kind of detail you get with Google Earth. To study planets within 100 light years, the instrument would require capabilities that outstrip those of Cash’s cluster of interferometrically communicating space telescopes:

At 100 light-years, something the size of a Honda Accord — which I propose as a standard imaging test object — subtends an angle of a half-trillionth of a second of arc. In case that number doesn’t speak to you, it’s roughly the apparent size of a cell nucleus on Pluto, as viewed from Earth.

You will not be stunned to hear that resolving something that minuscule requires a telescope with a honking size. At ordinary optical wavelengths, “honking” works out to a mirror 100 million miles across. You could nicely fit a reflector that large between the orbits of Mercury and Mars. Big, yes, but it would permit you to examine exoplanets in incredible detail.

Or, of course, you can do what Shostak is really getting at, which is to use interferometry to pool data from thousands of small mirrors in space spread out over 100 million miles, an array of the sort we are already building for radio observations and learning how to improve for optical and infrared work on Earth. Shostak discusses a system like this, which again is conceivable within the time-frame we are talking about for developing an actual interstellar probe, as a way to vanquish what he calls ‘the tyranny of distance.’ And, he adds, ‘You can forget deep space probes.’

I doubt we would do that, however, because we can hope that among the many worlds such a space-based array would reveal to us would be some that fire our imaginations and demand much closer study. The impulse to send robotic if not human crews will doubtless be fired by many of the exotic scenes we will observe. I wouldn’t consider this mammoth space array our only way of interacting with the galaxy, then, but an indispensable adjunct to our expansion into it.

Image: An early design for doing interferometry in space. This is an artist’s concept of the Terrestrial Planet Finder/Darwin mid-infrared formation flying array. Both TPF-I and Darwin were designed around the concept of telescope arrays with interferometer baselines large enough to provide the resolution for detecting Earth-like planets. Credit: T. Herbst, MPIA).

All this talk of huge telescopes triggered the memory of perhaps the ultimate instrument, dreamed up by science fiction writer Piers Anthony in 1969. It was Webster Cash’s Aragoscope that had me thinking back to this one, a novel called Macroscope that was nominated for the Hugo Award in the Best Novel Category in 1970. That’s not too shabby a nomination when you consider that other novels nominated that year were Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (the eventual winner), Robert Silverberg’s Up the Line, and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five.

The ‘macroscope’ of the title is a device that can focus newly discovered particles called ‘macrons,’ a fictional device that allows Anthony to create a telescope of essentially infinite resolution. He places it on an orbiting space station, from which scientists use it to discover exoplanets, observe alien races and even study their historical records. The macroscope is also a communications device used by intelligent aliens in ways the human observers do not understand. When a signal from a potential Kardashev Type II civilization is observed, a series of adventures ensue that result in discoveries forcing the issue of human interstellar travel.

So much happens in Macroscope that I’ve given away only a few of its secrets. Whether the novel still holds up I don’t know, as I last read it not long after publication. But the idea of a macroscope has stuck with me as the embodiment of the ultimate telescope, one that would surpass even the conjectures we’ve looked at above. Anthony’s macrons, of course, are fictional, but complex deep space arrays and interferometry are within our power, and I think we can imagine deploying these technologies to give us exoplanet close-ups as a project for the next century, or perhaps late in this one. What images they will return we can only imagine.

SETI: The Casino Perspective

I like George Johnson’s approach toward SETI. In The Intelligent-Life Lottery, he talks about playing the odds in various ways, and that of course gets us into the subject of gambling. What are the odds you’ll hit the right number combination when you buy a lottery ticket? Whenever I think about the topic, I always remember walking into a casino one long ago summer on the Côte d’Azur. I’ve never had the remotest interest in gambling, and neither did the couple we were with, but my friend pulled a single coin out of his pocket and said he was going to play the slots.

“This is it,” he said, holding up the coin, a simple 5 franc disk (this was before the conversion to the Euro). “No matter what happens, this is all I play.”

He went up to the nearest slot machine and dropped the coin in. Immediately lights flashed and bells rang, and what we later calculated as the equivalent of about $225 came pouring out. Surely, I thought, he’ll take at least one of these coins and play it again — it’s how gambling works. But instead, he headed for the door and we turned the money into a nice meal. $225 isn’t a huge hit, to be sure (not in the vicinity of Monte Carlo!), but calculating the value of the 5 franc coin at about a dollar, he did OK. As far as I know,none of us has ever gone back into a casino.

Image: The Palais de la Méditerranée in Nice. It’s possible to drop a lot of money in here fast, but we got out unscathed.

The odds on winning the grand prize in a lottery are formidable, and Johnson notes that a Powerball prize of $90 million, the result of hitting an arbitrary combination of numbers, went recently to someone who picked up a ticket at a convenience store in Colorado. The odds on that win were, according to Powerball’s own statistics, something like one in 175 million.

Evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr probably didn’t play the slots, but he used his own calculations of the odds to argue against Carl Sagan’s ideas on extraterrestrial civilizations. No way, said Mayr, intelligence is vanishingly rare. It took several billion years of evolution to produce a species that could build cities and write sonnets. If you’re thinking of the other inhabitants of spaceship Earth, consider that we are one out of billions of species that have evolved in this time. What slight tug in the evolutionary chain might have canceled us out altogether?

Johnson likewise quotes Stephen Jay Gould, who argued that so many chance coincidences put us where we are today that we should be awash in wonder at our very existence. We not only hit the Powerball numbers, but we kept buying tickets, and with each new ticket, we won again and got an even larger prize. Some odds!

For Gould, the fact that any of our ancestral species might easily have been nipped in the bud should fill us “with a new kind of amazement” and “a frisson for the improbability of the event” — a fellow agnostic’s version of an epiphany.

“We came this close (put your thumb about a millimeter away from your index finger), thousands and thousands of times, to erasure by the veering of history down another sensible channel,” he wrote. “Replay the tape a million times,” he proposed, “and I doubt that anything like Homo sapiens would ever evolve again. It is, indeed, a wonderful life.”

A universe filled with planets on which nothing more than algae and slime have evolved? Perhaps, but of course we can’t know this until we look, and I think Seth Shostak gets it right in an essay on The Conversation called We Could Find Alien Life, but Politicians Don’t Have the Will. Seth draws the distinction between searching for life per se, as we are engaged in on places like Mars, and searching for intelligent beings who use technologies to communicate. He’s weighing evolution’s high odds against the sheer numbers of stellar systems we’re discovering, and saying the idea of other intelligence in the universe is at least plausible.

And here the numbers come back into play because, despite my experience in the Nice casino, we’re unlikely to hit a SETI winner with only a few coins. Shostak points out that the proposed 2015 NASA budget allocates $2.5 billion for planetary science, astrophysics and related work including JWST — this encompasses spectroscopy to study the atmospheres of exoplanets, another way we might find traces of living things on other worlds, though not necessarily intelligent species. And while this figure is less than 1/1000th of the total federal budget in the US, the combined budgets for the SETI effort are a thousand times less than what NASA will spend.

“Of course, if you don’t ante up, you will never win the jackpot,” Shostak concludes, yet another gambling reference in a field that is used to astronomical odds and how we might defeat them. I have to say that Mayr’s analysis makes a great deal of sense to me, and so does Gould’s, but I’m with Shostak anyway. The reason is simple: We have no higher calling than to discover our place in the universe, and to do that, the question of whether or not other intelligent species exist is paramount. I’m one of those people who want to be proven wrong, and the way to do that is with a robust SETI effort working across a wide range of wavelengths.

And working, I might add, across a full spectrum of ideas. Optical SETI complements radio SETI, but we can broaden our SETI hunt to include the vast troves of astronomical data our telescopes are producing day after day. We have no notion of how an alien intelligence might behave, but we can look for evidence not only in transmissions but in the composition of stellar atmospheres and asteroid belts, all places we might find clues of advanced species modifying their environment. It is not inconceivable that we might one day find signs of structures, Dyson spheres or swarms or other manipulations of a solar system’s available resources.

So I’m with the gamblers on this. We may have worked out the Powerball odds, but figuring out the odds on intelligent life is an exercise that needs more than a single example to be credible. I’ll add that SETI can teach us a great deal even if we never find evidence of ETI. If we are alone in the galaxy, what would that say about our prospects as we ponder interstellar expansion? Would we, as Michael Michaud says, go on from this to ‘impose intention on chance?’ I think so, for weighing against our destructive impulses, we have a dogged need to explore. SETI is part of our search for meaning in the cosmos, a meaning we can help to create, nurture and sustain.

Did Stardust Sample Interstellar Materials?

Space dust collected by NASA’s Stardust mission, returned to Earth in 2006, may be interstellar in origin. We can hope that it is, because the Solar System we live in ultimately derives from a cloud of interstellar gas and dust, so finding particles from outside our system takes us back to our origins. It’s also a first measure — as I don’t have to tell this audience — of the kind of particles a true interstellar probe will encounter after it has left our system’s heliosphere, the ‘bubble’ in deep space blown out by the effects of the Sun’s solar wind.

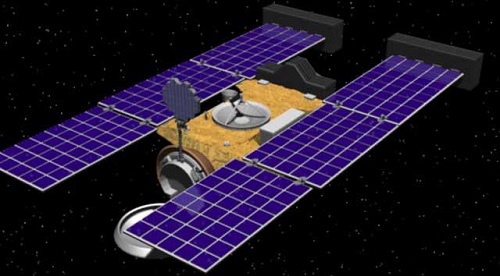

Image: Artist’s rendering of the Stardust spacecraft. The spacecraft was launched on February 7, 1999, from Cape Canaveral Air Station, Florida, aboard a Delta II rocket. It collected cometary dust and suspected interstellar dust and sent the samples back to Earth in 2006. Credit: NASA JPL.

The cometary material has been widely studied in the years since its return, but how to handle the seven potentially interstellar grains thus far found, and verify their origin? It’s not an easy task. Stardust exposed its collector on the way to comet Wild 2 between 2000 and 2002. Aboard the spacecraft, sample collection trays made up of aerogel and separated by aluminum foil trapped three of the potentially interstellar particles, which are only a tenth as large as Wild 2’s comet dust, within the aerogel, while four other particles of interest left pits and rim residue in the aluminum foil. At Berkeley, synchrotron radiation from the lab’s Advanced Light Source, along with scanning transmission x-ray and Fourier transform infrared microscopes, have ruled out many interstellar candidate dust particles because they are contaminated with aluminum.

The latter may have been knocked off the spacecraft to become embedded in the aerogel, but we’ll learn more as the work continues. The grains are more than a thousand times smaller than a grain of sand. To confirm their interstellar nature it will be necessary to measure the relative abundance of three stable isotopes of oxygen, says Andrew Westphal (UC-Berkeley), lead author of a paper published last week in Science. In this news release from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Westphal says that while the analysis would confirm the dust’s origin, the process would destroy the samples, which is why the team is hunting for more particles in the Stardust collectors even as it practices isotope analysis on artificial dust particles.

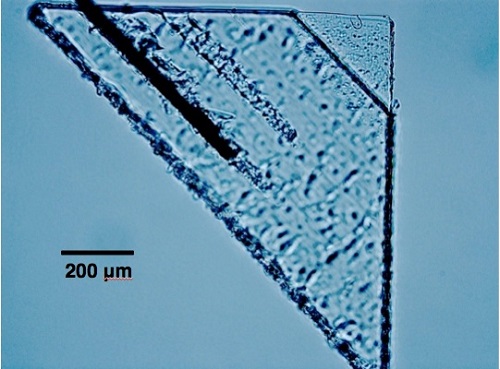

Image: The bulbous impact from the vaporized dust particle called Sorok can barely be seen as the thin black line in this section of aerogel in the upper right corner. Credit: Westphal et al. 2014, Science/AAAS.

So far the analysis has been entirely non-destructive and the results have been in some ways surprising. Twelve papers being published in Meteoritics & Planetary Science are outlining the methods now being deployed. Finding the grains has meant probing the aerogel panels by studying tiny photographic ‘slices’ at different visual depths, producing a sequence of millions of images that was turned into a video. A citizen science project called Stardust@home was a player in the analysis, using distributed computing and the eyes of volunteers to study the video to look for tracks caused by the dust. So far, more than 100 tracks have been found but not all have been analyzed, and only 77 of the 132 aerogel panels have been scanned.

So we have the potential for further finds. What we’re learning is that if this dust is indeed interstellar, it’s surprisingly diverse. Says Westphal:

“Almost everything we’ve known about interstellar dust has previously come from astronomical observations—either ground-based or space-based telescopes. The analysis of these particles captured by Stardust is our first glimpse into the complexity of interstellar dust, and the surprise is that each of the particles are quite different from each other.”

Image: The dust speck called Orion contained crystalline minerals olivine and spinel as well an an amorphous material containing magnesium, and iron. Credit: Westphal et al. 2014, Science/AAAS.

Two of the larger particles have a fluffy composition that Westphal compares to a snowflake, a structure not anticipated from earlier models of interstellar dust. Interestingly, they contain olivine, a mineral composed of magnesium, iron and silicon, which implicates disk material or outflows from other stars modified by its time in the interstellar deep. The fact that three of the particles found in the aluminum foil between tiles on the collector tray also contained sulfur compounds is striking, as its presence was not expected in interstellar particles. The ongoing analysis of the remaining 95 percent of the foils in the collector may help clarify the situation.

The paper is Westphal et al., “Evidence for Interstellar Origin of Seven Dust Particles Collected by the Stardust Spacecraft,” Science Vol. 345, No. 6198 (2014), pp. 786-791 (abstract).