Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Wolf 359: Of Gravitational Lensing and Galactic Networks

If self-reproducing probes have ever been turned loose in the Milky Way, they may well have spread throughout the galaxy. Our planet is 4.6 billion years old, but the galaxy’s age is 13 billion, offering plenty of time for this spread. A number of papers have explored the concept, including work by Frank Tipler, who in 1980 argued that even at the speed of current spacecraft, the galaxy could be completely explored within 300 million years. Because we had found no evidence of such probes, Tipler concluded that extraterrestrial technological civilizations did not exist.

Robert Freitas also explored the consequences of self-reproducing probes in that same year, reaching similar conclusions about how quickly they would spread, although not buying Tipler’s ultimate conclusion. It’s interesting that Freitas went to work on looking for evidence, reasoning that halo orbits around the Lagrangian points might be one place to search. He was, to my knowledge, the first to use the term SETA — Search for Extraterrestrial Artifacts — which has now come into common use, and is currently under examination by Jim Benford in his work on ‘lurkers.’

A new paper from Michaël Gillon (University of Liège) and Artem Burdanov (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) has now appeared that follows the implications of self-reproduction and technology, tying them to a more specific search regimen. Conversant with the work of Von Eshleman as well as Claudio Maccone, the authors ask whether using the gravitational lens offered by a star wouldn’t make the most reasonable method for ETI communications. The Sun’s huge magnifications, bending light from objects behind it as seen from a relay somewhere beyond its 550 AU lensing distance, could enable participation in a network that functioned on a galactic scale.

You probably remember Gillon as the man who led the team that discovered TRAPPIST-1’s planets. Back in 2014, he began his exploration of gravitational lensing and communications with the publication of a paper titled “A novel SETI strategy targeting the solar focal regions of the most nearby stars.” Accepting the idea that self-reproducing probes could spread through the galaxy in a span of hundreds of millions of years, the author opened the question of detectability. He drew on Maccone’s insight that links enabled by gravitational lensing could allow data-rich communications between two stars at extremely low power. It is in this 2014 paper that Gillon first proposes looking for leakage in traffic between star systems.

A civilization that has spread throughout the galaxy might set up such relays around any stars useful as network nodes. This would turn conventional SETI on its head. Rather than scanning for radio or optical signals from other stellar systems, we consider intercepting ongoing traffic between another star and the relay in our own system. A fully colonized galaxy, so the thinking goes, should have a relay around at least one nearby star.

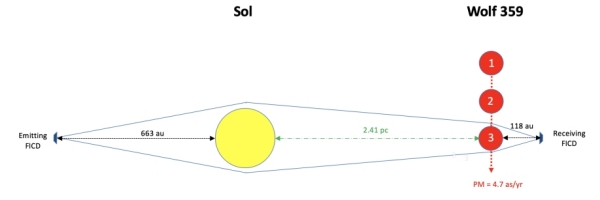

Thus the term Focal Interstellar Communication Devices (FICDs), examples of which could be present in our own Solar System and perhaps in the focal regions of nearby stars. Several studies have already appeared on a strategy of performing intense multi-spectral monitoring of these focal regions in the hopes of snagging communication leakage from such a network. Gillon and Burdanov focus on a specific FICD. They identify Wolf 359, an M-dwarf that is the third closest stellar system to our own, as a prime candidate to receive a signal from a local FICD, and implement an optical search.

Why Wolf 359? Ponder this:

…detecting the FICD emission to a nearby star can only be done if the observer is within one of these narrow beams, putting a stringent geometrical constraint on the project concept. For an Earth-based observer, this means that the Earth’s minimum impact parameter has to be close to 1 as seen from the FICD, and thus also from the targeted nearby star. In other words, the Earth has to be a transiting (or nearly transiting) planet for one of the nearest stars to give this SETI concept a chance of success, so the target star has to be very close to the ecliptic plane. With its nearly circular orbit and its semi-major axis 215 times larger than the solar radius, the Earth has a mean transit probability < 0.5% for any random star of the solar neighborhood.

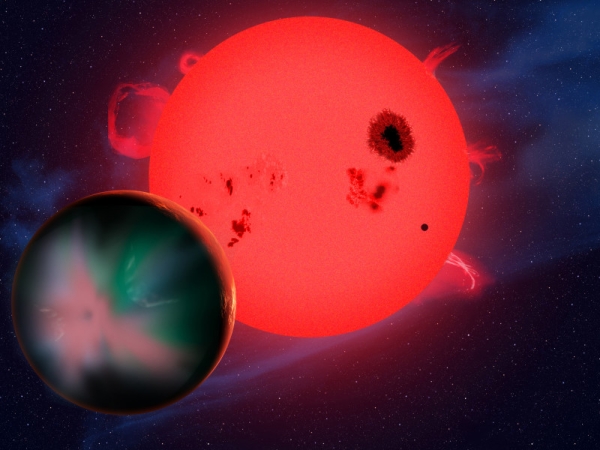

Image: An artist’s depiction of an active red dwarf star like Wolf 359 orbited by a planet. Credit: David A. Aguilar.

In other words, because the Earth transits the Sun as seen from Wolf 359, our planet would pass through any communication beam between the star and a local probe once per orbit. Thus a signal to Wolf 359 from an FICD in our Sun’s gravitational lensing region could in principle be detected. Gillon and Burdanov put the idea to the test using the TRAPPIST-South and SPECULOOS Southern Observatory in Chile, in a search “sensitive enough to detect constant emission with emitting power as small as 1W.”

The result: No detections. This could indicate that no probes exist within the Solar System using these methods, or at least that such a probe did not transmit during the observations. Indeed, the list of hypotheses to explain a null result is so large that no conclusion can be drawn. No detection simply means no detection.

But the observations lead us further to consider the spectral range of possible emissions from FICD to star. This is going to change depending on the star. Remember that using gravitational lensing to enable communications forces the receiver to face the host star, blocking its light with some kind of occulter (or perhaps a coronagraph) while enabling the signal to be received. Gillon and Burdanov note that Wolf 359 is a flare star with strong coronal activity, one with significant emission of X-ray and extreme ultraviolet light. The authors determine ‘a spectral zone of minimal emission’ that becomes interesting as a communications channel. Here let’s turn back to the paper, for this zone may be a better place to look:

While the very low emission of late-type M-dwarfs in this spectral range could be an issue for prebiotic chemistry on habitable planets (Rimmer et al. 2018), it could represent a nice spectral ‘sweet spot’ for a GL-based communication to a late M-dwarf like Wolf 359 or TRAPPIST-1. Another advantage of using this wavelength range instead of the optical range is the improved emission rate, thanks to the narrower laser beams… These considerations suggest that the spectral ranges 300-920nm and 400-950nm probed by the TRAPPIST-South and SPECULOOS South observations could not correspond to the optimal spectral range for a GL-based communication [gravitational lensing] from the solar system to Wolf 359. The 150-250 nm spectral range could represent a more optimal spectral range for such GL-based interstellar communication to a cold and active late-type M-dwarf like Wolf-359.

Image: This is Figure 2 from the paper. Caption: Illustration showing the geometry of the hypothesized communication link from the solar system to the Wolf 359 system. The distances and stellar sizes are not to scale. Wolf 359 is shown at 3 different positions. Position 1 corresponds to the time of the emission of the photons that we receive from it now. Position 2 corresponds to its current position. Position 3 corresponds to the time it will receive the photons emitted now by the FICD. Credit: Gillon & Burdanov.

Probing this spectral range would require a space-based instrument, but it would be interesting to target these frequencies in a reproduction of the Wolf 359 observations. This paper recounts the first attempt to detect optical messages emitted from the Solar System to this star, and as such seems intended primarily as a way to shake out observing methods and explore how gravitational lens-based networking could be observed.

The paper is Gillon & Burdanov, “Search for an alien communication from the Solar System to a neighbor star,” submitted to Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (preprint). Gillon’s 2014 paper is ” “A novel SETI strategy targeting the solar focal regions of the most nearby stars,” Acta Astronautica Vol. 94, Issue 2 (February 2014), 629-633 (abstract).

Deep Learning Methods Flag 301 New Planets

It’s no small matter to add 301 newly validated planets to an exoplanet tally already totalling 4,569. But it’s even more interesting to learn that the new planets are drawn out of previously collected data, as analyzed by a deep neural network. The ‘classifier’ in question is called ExoMiner, describing machine learning methods that learn by examining large amounts of data. With the help of the NASA supercomputer called Pleiades, ExoMiner seems to be a wizard at separating actual planetary signatures from the false positives that plague researchers.

ExoMiner is described in a paper slated for The Astrophysical Journal, where the results of an experimental study are presented, using data from the Kepler and K2 missions. The data give the machine learning tools plenty to work with, considering that Kepler observed 112,046 stars in its 115-degree square search field, identifying over 4000 candidates. More than 2300 of these have been confirmed. The Kepler extended mission K2 detected more than 2300 candidate worlds, with over 400 subsequently confirmed or validated. The latest 301 validated planets indicate that ExoMiner is more accurate than existing transit signal classifiers.

How much more accurate? According to the paper, ExoMiner retrieved 93.6% of all exoplanets in its test run, as compared to a rate of 76.3% for the best existing transit classifier.

We see many more candidate planets than can be readily confirmed or identified as false positives in all our large survey missions. TESS, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, for example, working with an area 300 times larger than Kepler’s, has detected 2241 candidates thus far, with about 130 confirmed. Obviously, pulling false positives out of the mix is difficult using our present approaches, which is why the ExoMiner methods are so welcome.

Hamed Valizadegan is ExoMiner project lead and machine learning manager with the Universities Space Research Association at NASA Ames:

“When ExoMiner says something is a planet, you can be sure it’s a planet. ExoMiner is highly accurate and in some ways more reliable than both existing machine classifiers and the human experts it’s meant to emulate because of the biases that come with human labeling…Now that we’ve trained ExoMiner using Kepler data, with a little fine-tuning, we can transfer that learning to other missions, including TESS, which we’re currently working on. There’s room to grow.”

Image: Over 4,500 planets have been found around other stars, but scientists expect that our galaxy contains millions of planets. There are multiple methods for detecting these small, faint bodies around much larger, brighter stars. The challenge then becomes to confirm or validate these new worlds. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

The paper describes the most common approach to detecting exoplanet candidates and vetting them. Imaging data are processed to identify ‘threshold crossing events’, after which a transit model is fitted to each signal, with diagnostic tests applied to subtract non-exoplanet effects. This produces data validation reports for these crossing events, which in turn are filtered to identify likely exoplanets. The data validation reports for the most likely events are then reviewed by vetting teams and released as objects of interest for follow-up work.

Machine learning (ML) methods speed the process. As described in the paper:

ML methods are ideally suited for probing these massive datasets, relieving experts from the time-consuming task of sifting through the data and interpreting each DV report, or comparable diagnostic material, manually. When utilized properly, ML methods also allow us to train models that potentially reduce the inevitable biases of experts. Among many different ML techniques, Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) have achieved state-of-the-art performance (LeCun et al. 2015) in areas such as computer vision, speech recognition, and text analysis and, in some cases, have even exceeded human performance. DNNs are especially powerful and effective in these domains because of their ability to automatically extract features that may be previously unknown or highly unlikely for human experts in the field to grasp…

The ExoMiner software learns by using data on exoplanets that have been confirmed in the past, and also by examining the false positives thus far generated. Given the sheer numbers of threshold crossing events Kepler and K2 have produced, automated tools to examine these massive datasets greatly facilitate the confirmation process. Remember that two goals are defined here. A ‘confirmed’ planet is one that is detected via other observational techniques, as when radial velocity methods, for example, are applied to identify the same planet.

A planet is ‘validated’ statistically when it can be shown how likely the find is to be a planet based on the data. The 301 new exoplanets are considered machine-validated. They have been in candidate status until ExoMiner went to work on them to rule out false positives. As with the analysis we examined yesterday, refining filtering techniques at Proxima Centauri to screen out flare activity, this work will be applied to future catalogs from TESS and the ESA’s PLATO mission. According to Valizadegan, the team is already at work using ExoMiner with TESS data.

Usefully, ExoMiner offers what the authors call “a simple explainability framework” that provides feedback on the classifications it makes. It isn’t a ‘black box,’ according to exoplanet scientist Jon Jenkins (NASA Ames), who goes on to say: “We can easily explain which features in the data lead ExoMiner to reject or confirm a planet.”

Looking forward, the authors explain the keys to ExoMiner’s performance. The reference to Kepler Objects of Interest (KOIs) below refers to a subset defined within the paper:

[S]ince the general concept behind vetting transit signals is the same for both Kepler and TESS data, and ExoMiner utilizes the same diagnostic metrics as expert vetters do, we expect an adapted version of this model to perform well on TESS data. Our preliminary results on TESS data verify this hypothesis. Using ExoMiner, we also demonstrate that there are hundreds of new exoplanets hidden in the 1922 KOIs that require further follow-up analysis. Out of these, 301 new exoplanets are validated with confidence using ExoMiner.

The paper is Valizadegan et al., “ExoMiner: A Highly Accurate and Explainable Deep Learning Classifier to Mine Exoplanets,” accepted at The Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

Proxima Centauri: Transits Amidst the Flares?

Discovered in 1915, Proxima Centauri has been a subject of considerable interest ever since, as you would expect of the star nearest to our own. But I had no idea research into planets around Proxima went all the way back to the 1930s. Nonetheless, a new paper from Emily Gilbert (University of Chicago) and colleagues mentions a 1938 attempt by Swedish astronomer Erik Holmberg to use astrometric methods to search for one or more Proxima planets. The abstract of the Holmberg paper (citation below) reads in part:

Many parallax stars show periodic displacements. These effects probably are to be explained as perturbations caused by invisible companions. Since the amplitudes of the orbital motion are very small, the masses of the companions will generally be very small, too. Thus Proxima Centauri probably has a companion, the mass of which is only some few times larger than the mass of Jupiter. A preliminary investigation gives the result that 25% of the total number of parallax stars may have invisible companions.

Holmberg (1908-2000) seems to be best known for his work on galaxy interactions, but the movement of nearby stars was clearly a lively interest. I think we can assume that the Proxima ‘detection’ was due to systematic factors; i.e., noise in the data. But because I was fascinated by this early flurry of exoplanet hunting, I dug around a bit in Michael Perryman’s The Exoplanet Handbook (Cambridge University Press, 2011) to learn that Holmberg came back in 1943 to use long-term time-series photographic plates in another astrometric hunt, this one at 70 Ophiuchi (he thought he detected a gas giant), while in the same year, the Danish astronomer Kaj Aage Gunnar Strand (1907-2000) found evidence for a 16-Jupiter mass planet around 61 Cygni. Neither of these worlds turned out to be any more real than Holmberg’s putative planet at Proxima Centauri.

So exoplanet hunting is replete with false positives. We’ve talked at some length in these pages about the work of Peter van de Kamp (1901-1995), a Dutch astronomer living in the US, on possible planets at Barnard’s Star. His detections were ultimately shown to have resulted from systematic errors in his equipment (though unless I am mistaken, he never accepted this conclusion). Van de Kamp’s work in the 1960s and later made the point that a small number of astronomers have been actively searching for exoplanets long before the detection of 51 Pegasi b, but the Holmberg paper, taking us back prior to World War II, came as a surprise I wanted to share.

Searching for Transits

On to today’s work on Proxima Centauri, which as we know has no gas giant of the sort Holmberg deduced, but does host at least two planets, among which is the fascinating Proxima Centauri b, the latter in the habitable zone of the star. Habitability, however, is problematic. Proxima is a flare star, so active that the atmosphere of a habitable zone planet may be threatened by the intense radiation, with obvious implications for surface life.

Proxima’s flares can dominate observation, as this passage from today’s paper makes clear:

We see 2-3+ large flares every day in the 2-minute cadence TESS light curve (Vida et al., 2019), and even with TESS 2-minute cadence, optical photometry, it can be hard to fully resolve flare morphology in order to search for transits. Davenport et al. (2016) even suggest that the visible-light light curve of Proxima Centauri may be so dominated by flares that the time series can be thought of as primarily a superposition of many flares.

Image: Proxima Centauri is a “flare star,” meaning that convection processes within the star’s body make it prone to random and dramatic changes in brightness. The convection processes not only trigger brilliant bursts of starlight but, combined with other factors, mean that Proxima Centauri is in for a very long life. Astronomers predict that this star will remain middle-aged — or a “main sequence” star in astronomical terms — for another four trillion years, some 300 times the age of the current Universe. These observations were taken using Hubble’s Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2). Its two companions, Alpha Centauri A and B, lie out of frame. Credit: NASA/ESA.

Indeed, Proxima’s flares appear nearly continuous, occurring at a range of wavelengths. Flares can induce shifts in radial velocity measurements, making observations noisy and burying a potential planetary signal in a sea of misleading data. The same problem occurs for transit detection, where flare-induced variations in the lightcurve may mask an actual planetary signature. All this makes clear what fine work Guillem Anglada-Escudé and team performed at unpacking the radial velocity data that first revealed the existence of Proxima b in 2016.

Because flare activity may be masking transits at Proxima Centauri, Gilbert and team modeled the stellar activity in their planet search algorithm, refining the result. Previous flare detection algorithms have tried to identify the flares and remove them, revealing the more stable stellar signal beneath. The authors take a different approach, using their own algorithm to first identify flares, then modeling them using a template, subtracting them from the data and running a transit search on the result. The unique flare modeling they apply to Proxima, painstakingly presented in the paper’s section on methods, involves a multi-step process of filtering and fitting the flare data. The scientists injected transits into the light curves before modeling as a way of determining how sensitive their method was, with results that boosted the planet signal.

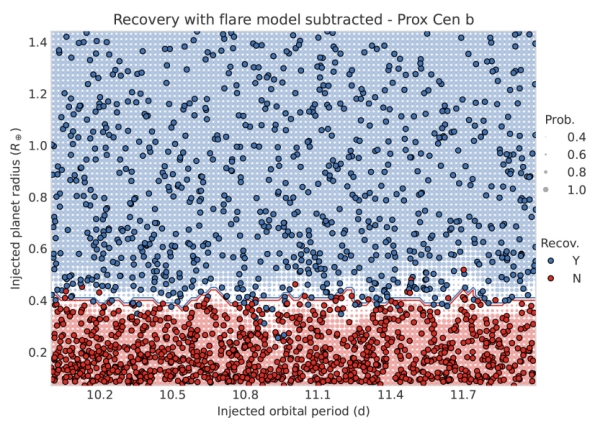

Image: This is Figure 3 from the paper. Caption: By subtracting a flare model from the light curve of Proxima Centauri, we are able to significantly increase the probability of recovering small planets. We are able to reliably recover planets down to around the radius of Mars across the period range searched, effectively ruling out any transit of Proxima Centauri b. Credit: Gilbert et al.

A transit at Proxima Centauri would be a huge boon to astronomers, allowing a precise radius and accurate determination of the composition of Proxima Centauri b (the same is true, of course, of Proxima c). Moreover, Proxima b’s short orbital period would mean frequent transits, and thus would elevate its status as a place to look for biosignatures in the atmosphere.

Alas, we have no transits. Gilbert’s team used TESS observations of Proxima Centauri to make this determination. The conclusion seems tight. From the paper:

We find no evidence for Proxima Centauri b in TESS data. This is not surprising because previous efforts using different telescopes have been similarly fruitless.

Using the known minimum mass of Proxima Centauri b (Msini = 1.27 M?), we used the relationship from Chen and Kipping (2017) to derive an expected planet radius to be R = 1.08 ± .14 R?. A 100% Iron planet would have an expected radius of 0.88 R? (Zeng et al., 2019). Therefore, given our injection and recovery tests show that no planets larger than 0.4 R? transit Proxima Centauri at periods between 10–12 days, we are confident that we would recover the signal from Proxima Centauri b if it were to transit.

The team’s flare modeling is a big part of the story here, improving the sensitivity to transiting planets from 0.6 Earth radii to 0.4, and allowing the team to put rigorous limits on the probability of transits. According to the authors, this kind of flare modeling is a technique that should be applicable to all active stars. This is good news for the continuing work of TESS and the future work of Plato (ESA’s PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars mission). Our sensitivity to small planets transiting low-mass, nearby active stars receives a boost from these methods, even though the search for transits at Proxima Centauri comes up empty.

The paper is Gilbert et al., “No Transits of Proxima Centauri Planets in High-Cadence TESS Data,” accepted at Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences (preprint). The Holmberg paper is Holmberg, E., “Invisible Companions of parallax stars revealed by means of modern trigonometric parallax observations,” Meddelanden fran Lunds Astronomiska Observatorium, Series II 92, 5–25.

Wind Rider: A High Performance Magsail

Can you imagine the science we could do if we had the capability of sending a probe to Jupiter with travel time of less than a month? How about Neptune in 18 weeks? Alex Tolley has been running the numbers on a concept called Wind Rider, which derives from the plasma magnet sail he has analyzed in these pages before (see, for example, The Plasma Magnet Drive: A Simple, Cheap Drive for the Solar System and Beyond). The numbers are dramatic, but only testing in space will tell us whether they are achievable, and whether the highly variable solar wind can be stably harnessed to drive the craft. A long-time contributor to Centauri Dreams, Alex is co-author (with Brian McConnell) of A Design for a Reusable Water-Based Spacecraft Known as the Spacecoach (Springer, 2016), focusing on a new technology for Solar System expansion.

by Alex Tolley

In 2017 I outlined a proposed magnetic sail propulsion system called the Plasma Magnet that was presented by Jeff Greason at an interstellar conference [6]. It caught my attention because of its simplicity and potential high performance compared to other propulsion approaches. For example, the Breakthrough Starshot beamed sail required hugely powerful and expensive phased-array lasers to propel a sail into interstellar space. By contrast, the Plasma Magnet [PM] required relatively little energy and yet was capable of propelling a much larger mass at a velocity exceeding any current propulsion system, including advanced solar sails.

The Plasma Magnet was proposed by Slough [5] and involved an arrangement of coils to co-opt the solar wind ions to induce a very large magnetosphere that is propelled by the solar wind. Unlike earlier proposals for magnetic sails that required a large electric coil kilometers in diameter to create the magnetic field, the induction of the solar wind ions to create the field meant that the structure was both low mass and that the size of the resulting magnetic field increased as the surrounding particle density declined. This allowed for a constant acceleration as the PM was propelled away from the sun, very different from solar sails and even magsails with fixed collecting areas.

The PM concept has been developed further with a much sexier name: the Wind Rider, and missions to use this updated magsail vehicle are being defined.

Wind Rider was presented at the 2021 Division of Planetary Sciences (DPS) meeting by the team led by Brent Freeze, showing their concept of the design for a Jupiter mission they called JOVE. The December meeting of the American Geophysical Union was the venue for a different Wind Rider concept mission to the SGL, called Pathfinder.

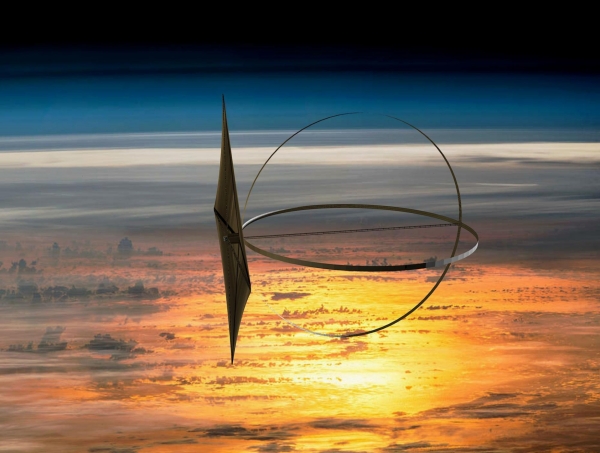

The main upgrade from the earlier PM to the Wind Rider is the substitution of superconducting coils. This allows the craft to maintain the magnetic field without requiring constant power to maintain the electric current, reducing the required power source. Because the superconducting coils would quickly heat up in the inner system and lose their superconductivity, a gold foil reflective sun shield is deployed to shield the coils from the sun’s radiation. This is shown in the image above with the shield facing the sun to keep the coils in shadow. The shield is also expected to do double duty as a radio antenna, reducing the net parasitic mass on the vehicle.

The performance of the Wind Rider is very impressive. Calculations show that it will accelerate very rapidly and reach the velocity of the solar wind, about 400 km/s. This has implications for the flight trajectory of the vehicle and the mission time.

The first mission proposal is a flyby of Jupiter – Jupiter Observing Velocity Experiment (JOVE) – much like the New Horizons mission did at Pluto.

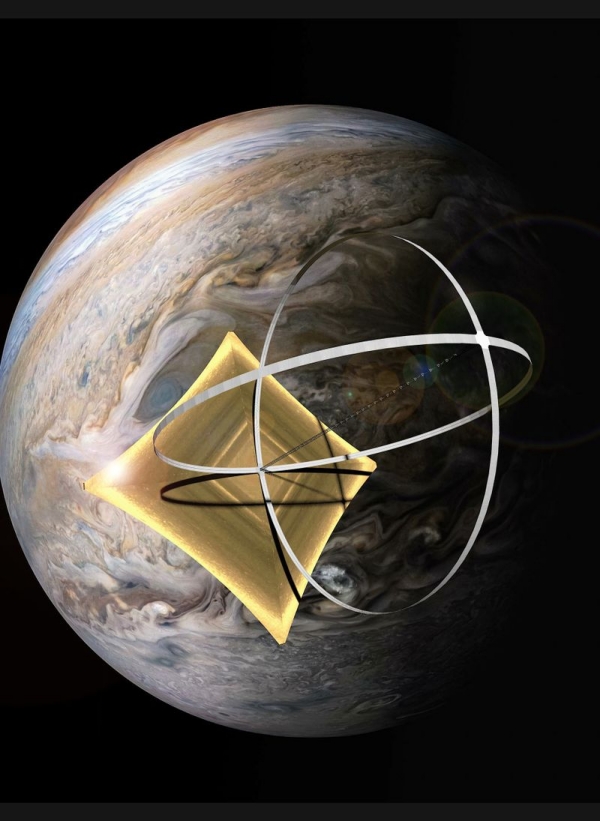

Figure 1. The Wind Rider on a flyby of Jupiter. The solar panels are hidden behind the sun shield facing the sun. The 16U CubeSat chassis is at the intersection of the 2 coils and sun shield.

The JOVE mission proposal is for an instrumented flyby of Jupiter [2]. The chassis is a 16U CubeSat. The scientific instrument payload is primarily to measure data on the magnetic field and ion density around Jupiter. The sail is powered by 4 solar panels that also double as struts to support the sun shield and generate about 1300 W at 1 AU and fall to about 50W at Jupiter.

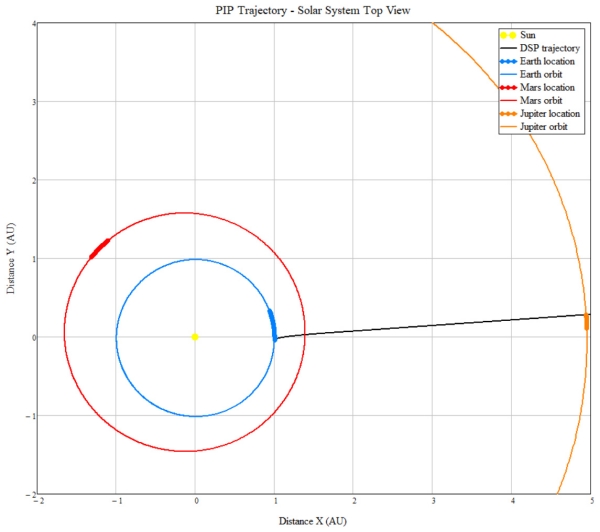

Figure 2. Trajectory of the Wind Rider from Earth to Jupiter

The flight trajectory is effectively a beeline directly to Jupiter, starting the flight almost at opposition. No gravity assists from Earth or Venus are required, nor a long arcing trajectory to intercept Jupiter. Figure 2 shows the trajectory, which is almost a straight-line course with the average velocity close to that of the solar wind.

Although the mission is planned as a flyby, a future mission could allow for orbital insertion if the craft approaches Jupiter’s rotating magnetosphere to maximize the impinging field velocity. Although not mentioned by the authors, it should be noted that Slough has also proposed using a PM as an aerobraking shield that decelerates the craft as it creates a plasma in the upper atmosphere of planets.

How does the performance of the Wind Rider compare to other comparable missions?

The JUNO space probe to Jupiter had a maximum velocity of about 73 km/s as Jupiter’s gravity accelerated the craft towards the planet. The required gravity assists and long flight path, about 63 AU or over 9 billion km, mean that its average velocity was about 60 km/s. This is not the fairest comparison as the JUNO probe had to attain orbital insertion at Jupiter.

A fairer comparison is the fastest probe we have flown – the New Horizons mission to Pluto — which reached 45 km/s as it left Earth but slowed to 14 km/s as it flew by Pluto. New Horizons took 1 year to reach Jupiter to get a gravity assist for its 9 year mission to Pluto, and therefore a maximum average velocity of 19 km/s between Earth and Jupiter.

Wind Rider can reach Jupiter in less than a month. Figure 2 shows the almost straight-line trajectory to Jupiter. Launched just before opposition, Wind Rider reaches Jupiter in just over 3 weeks. Because opposition happens annually, a new mission could be launched every year.

As the Wind Rider quickly reaches its terminal velocity at the same velocity as the solar wind, it can reach the outer planets with comparably short times with the same trajectory and annual launch windows.

The Wind Rider can fly by Saturn in just 6 weeks, and Neptune in 18 weeks. Compare that to the Voyager 2 probe launched in 1977 that took 4 years and 12 years to fly by the same planets respectively. Pluto could be reached by Wind Rider in just 6 months.

Because of its high terminal velocity that does not reduce during its mission, the Wind Rider is also ideally suited for precursor interstellar missions.

The second proposed mission is called Pathfinder [1], proposed to ultimately reach the solar gravity focal line around 550 AU from the sun. Flight time is less than 7 years, making this a viable project for a science and engineering team and not a multi-generation one based on existing rocket propulsion technology. As the flight trajectory is a straight line, this makes the craft well suited to follow the focal line while imaging a target star or exoplanet using the sun’s diameter as a large aperture telescope to increase the resolving power.

As the Wind Rider reaches the solar wind velocity, it may even be able to ride the gusts of higher solar wind velocities, perhaps reaching closer to 550 km/s.

While solar sails have been considered the more likely means to reach high velocities, especially when making sun-diver maneuvers, even advanced sails with proposed areal densities well below anything available today would reach solar system escape velocities in the range of 80-120 km/s [3]. If the Wind Rider can indeed reach the velocity of the solar wind, it would prove a far faster vehicle than any solar sail being planned, and would not need a boost from large laser arrays, nor risky sun-diver maneuvers.

I would inject some caution at this point regarding the performance. The performance is based entirely on theoretical work and a small scale laboratory experiment. What is needed is a prototype launched into cis-lunar space to test the performace on actual hardware and confirm the capability of the technology to operate as theorized.

It should also be noted that despite its theoretical high performance, there is a potential issue with propelling a probe with a magnetic sail. Compared to a solar sail or a vehicle with reaction thrusters, the Wind Rider as described so far has no crosswind capability. It just runs in front of the solar wind like a dandelion seed in the wind. This means that it would have to be aimed very accurately at its target, and subject to the vagaries of the strength of the solar wind that is far less stable than the sun’s photon emissions. Like the dandelion, if the Wind Rider was very inexpensive, many could be launched in the expectation that at least one would successfully reach its target.

However, there is a possibility that some crosswind capability is possible. This is based on modelling by Nishida [4]. This paper was recommended by Dr. Freeze [7].

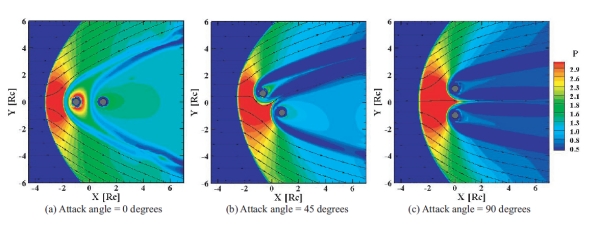

The study modeled the effect of the angle of attack of the magnetic field of a coil against the solar wind. The coil in this case would represent the induced circular movement of the solar wind induced by the primary Wind Rider/PM coils.

Theoretically, the angle of attack has an impact on the total force pushing past the magnetic field.

Figure 3 shows the pressure and on the field as the coil is rotated from 0 through 45 and 90 degrees to the solar wind.

The force experienced is maximal at 90 degrees. This is shown visually in figure 3 and graphically in figure 4.

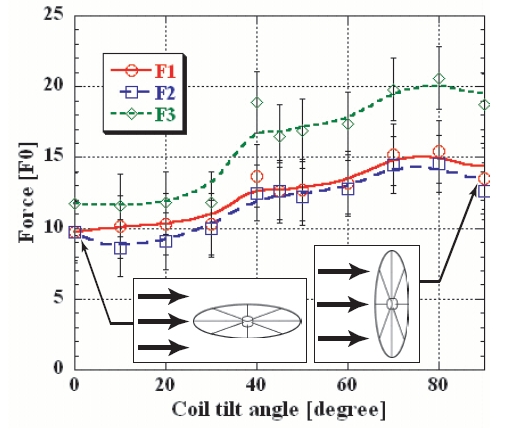

Figure 4. Force on the coil effected by angle of attack. A near 90 degrees angle of attack increases the force about 50%.

The angle of attack also induces a change in the thrust vector experienced by the coil, which would act as a crosswind maneuvering capability, allowing for trajectory adjustments as well as a longer launch window for the Wind Rider.

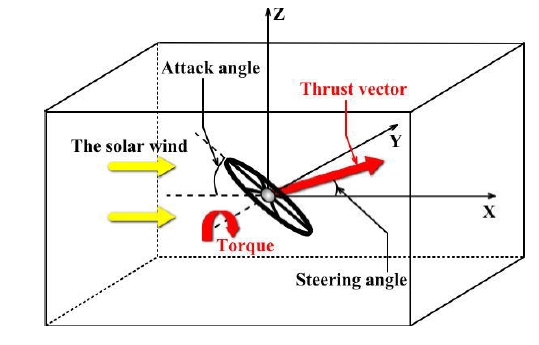

Figure 5. The angle of attack affects the thrust vector. But note the countervailing torque on the coil.

If the coil can maintain an angle of attack with respect to teh solar wind, then the Wind Rider can steer across the solar wind to some extent.

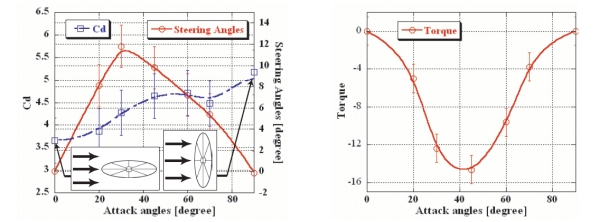

Figure 6. (left) Angle of attack, and steering angle. (right) angle of attack and the torque on the coil.

Figure 6 shows that the craft could steer up to 12 degrees away from the solar wind direction. However, maintaining that angle of attack requires a constant force to oppose the torque restoring the angle of attack to zero or 90 degrees. The coil therefore acts like a weather vane, always trying to align itself with the solar wind. To maintain the angle of attack would be difficult. Reaction wheels like those on the Kepler telescope could only act in a transient manner. Another possibility suggested is to move the center of gravity of the craft in some way. Adding booms with coils might be another solution, albeit by adding mass and complexity, undesirable for this first generation probe. Jeff Greason has an upcoming paper to be published in 2022 on theoretical navigation with possible ranges of steering capability.

In summary, the Wind Rider is an upgraded version of the Plasma Magnet propulsion concept, now applied to a reference design for 2 missions, a fast flyby of Jupiter, and an interstellar precursor mission that could reach the solar gravity lens focus. The performance of the design is primarily based on modelling and as yet there is no experimental evidence to support a finite lift/drag ratio for the craft.

Having said that, the propulsion principle and hardware necessary are not expensive, and there seems to be much interest by the AIAA. Maybe this propulsion method can finally be built, flown and evaluated. If it works as advertised, it would open up the solar system to exploration by fast, cheap robotic probes and eventually crewed ships.

References

1. Freeze, B et al Wind Rider Pathfinder Mission to Trappist-1 Solar Gravitational Lens Focal Region in 8 Years (poster at AGU – Dec 13th, 2021). https://agu.confex.com/agu/fm21/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/796237

2. Freeze, B et al Jupiter Observing Velocity Experiment (JOVE), Introduction to Wind Rider Solar Electric Propulsion Demonstrator and Science Objective.

https://baas.aas.org/pub/2021n7i314p05/release/1

3. Vulpetti, Giovanni, et al. (2008) Solar Sails: A Novel Approach to Interplanetary Travel. New York: Springer, 2008.

4. Nishida, Hiroyuki, et al. “Verification of Momentum Transfer Process on Magnetic Sail Using MHD Model.” 41st AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, 2005.

https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2005-4463

5. Slough, J. “Plasma Magnet NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts Phase I Final Report.” 2004. http://www.niac.usra.edu/files/studies/final_report/860Slough.pdf. See Figure 2.

6. Tolley, A “The Plasma Magnet Drive: A Simple, Cheap Drive for the Solar System and Beyond” (2017).

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2017/12/29/the-plasma-magnet-drive-a-simple-cheap-drive-for-the-solar-system-and-beyond/

7. Generous email communications with Dr. Brent Freeze in preparation of this article.

TOLIMAN Targets Centauri A/B Planets

We talked about the TOLIMAN mission last April, and the renewed interest in astrometry as the key to ferreting out possible planets around Alpha Centauri A and B. I was fortunate enough to hear Peter Tuthill (University of Sydney), who leads the team that has been developing the concept, rough out the idea at Breakthrough Discuss five years ago; Céline Bœhm (likewise at the University of Sydney) reported on more recent work at the virtual Breakthrough Discuss session this past spring. We now have an announcement from scientists involved that the space telescope mission will proceed.

Eduardo Bendek (JPL) is a member of the TOLIMAN team:

“Even for the very nearest bright stars in the night sky, finding planets is a huge technological challenge. Our TOLIMAN mission will launch a custom-designed space telescope that makes extremely fine measurements of the position of the star in the sky. If there is a planet orbiting the star, it will tug on the star betraying a tiny, but measurable, wobble.”

Work on the mission heated up in April of this year, with scientists from the University of Sydney working in partnership with Breakthrough Initiatives, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Australia’s Saber Astronautics. The mission could revolutionize our view of Centauri A and B, according to Tuthill:

“Astronomers have access to amazing technologies that allow us to find thousands of planets circling stars across vast reaches of the galaxy. Yet we hardly know anything about our own celestial backyard. It is a modern problem to have; we are like net-savvy urbanites whose social media connections are global, but we don’t know anyone living on our own block… Getting to know our planetary neighbors is hugely important. These next-door planets are the ones where we have the best prospects for finding and analyzing atmospheres, surface chemistry and possibly even the fingerprints of a biosphere – the tentative signals of life.”

Image: The University of Sydney’s Peter Tuthill, project leader for TOLIMAN. Credit: University of Sydney.

Astrometry tracks the minute changes in the position of a star that are the result of the gravitational pull of a planet. Detection of tiny angular displacements of the star allows the planet’s mass and orbit to be recovered, and unlike the situation with both radial velocity and transit methods, the astrometric signal increases with the separation of the planet and star.

That takes us out to the orbital distance for an Earth-class planet to be in the habitable zone, even though the signal is tiny, in the range of micro-arcseconds for the Alpha Centauri binary. The astrometric signal from an Earth-class planet orbiting in the habitable zone of Centauri A is 2.5 micro-arcseconds; a similar planet around Centauri B is roughly half of that.

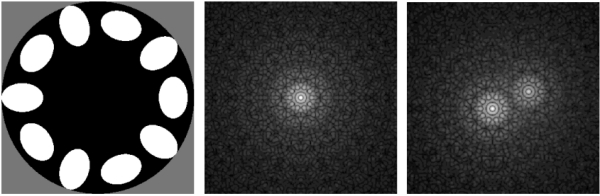

TOLIMAN uses what the team calls a ‘diffractive pupil’ lens that spreads out the starlight and allows scientists to eliminate systematic errors and clarify the underlying signal. The flower-like pattern enhances the detection of star movement without the need for field stars as references, eliminating the need for a large aperture (such stars demand a larger collecting area). The pattern also reduces noise levels in the detector. An online description of the TOLIMAN technology explains why the nearest stellar system makes an excellent target for these methods:

With the fortuitous presence of a bright phase reference only arcseconds away, measurements are immediately 2 – 3 orders of magnitude more precise than for a randomly chosen bright field star where many-arcminute fields (or larger) are required to find background stars for this task. Maintaining the instrument imaging distortions stable over a few arcseconds is considerably easier than requiring similar stability over arcminutes or degrees. Alpha Cen’s proximity to Earth means that the angular deviations on the sky are proportionately larger (typically a factor of ~10-100 compared to a population of comparably bright stars).

Image: This is from Figure 3 of the online description of TOLIMAN referenced above. Caption: Left: pupil plane for TOLIMAN diffractive-aperture telescope. Light is only collected in the 10 elliptical patches (the remainder of the pupil is opaque in this conceptual illustration, although our flight design will employ phase steps which do not waste starlight). Middle: The simulated image observing a point-source star with this pupil. The region surrounding the star can be seen to be filled with a complex pattern of interference fringes, comprising our diffractive astrometric grid. Right: A simulated image of the Alpha Cen binary star as observed by TOLIMAN. Credit: Tuthill et al.

The same description refers to TOLIMAN as a ‘modest astrometric space telescope,’ and the word ‘modest’ seems to apply in that this is a narrow-field instrument 30cm in diameter, with what proponents estimate is a fast build time on the order of 18 months. We might contrast the mission with existing astrometric missions like the European Space Agency’s space-based GAIA. The latter can make astrometric measurements in the 10s of micro-arcseconds, which basically means it is capable of detecting gas giants. TOLIMAN takes us into the realm of much smaller, rocky worlds. Because it has no need of a large aperture, it is small, inexpensive and, obviously, tightly focused on a nearby system rather than surveying a large star field.

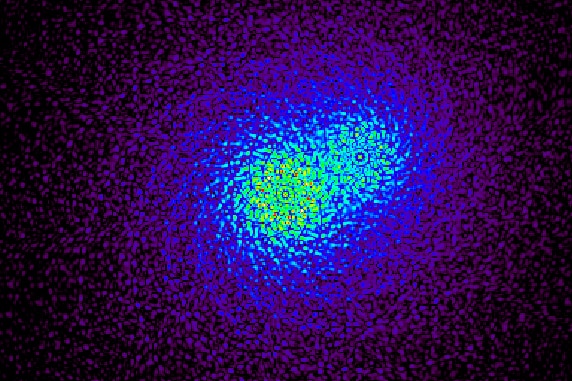

Image: Simulated image of the Alpha Centauri system, as could be viewed by the TOLIMAN telescope. Credit: Peter Tuthill.

TOLIMAN will receive spaceflight mission operations support from Saber Astronautics, including satellite communications and command. Saber’s involvement, says Tuthill, is “a critical part of the mission.” The company has received A$788,000 from an Australian Government International Space Investment: Expand Capability grant for the telescope’s design and construction, and I rather like the spirit in CEO Jason Held’s comment on TOLIMAN:

“TOLIMAN is a mission that Australia should be very proud of – it is an exciting, bleeding-edge space telescope supplied by an exceptional international collaboration. It will be a joy to fly this bird.”

As to when we can expect the bird to fly, Tuthill speaks of launch by 2023. We might know by mid-decade whether an Earth-size rocky planet orbits Centauri A or B. Habitable zone orbits are possible around both stars.

An early description of TOLIMAN is Tuthill et al., “The TOLIMAN Space Telescope,” Proc. SPIE 10701, Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging VI, 107011J (9 July 2018). Abstract.

Probing the Likelihood of Panspermia

I’m looking at a paper just accepted at The Astrophysical Journal on the subject of panspermia, the notion that life may be distributed through the galaxy by everything from interstellar dust to comets and debris from planetary impacts. We have no hard data on this — no one knows whether panspermia actually occurs from one planet to another, much less from one stellar system to another star. But we can investigate possibilities based on what we know of everything from the hardiness of organisms to the probabilities of ejecta moving on an interstellar trajectory.

In “Panspermia in a Milky Way-like Galaxy,” lead author Raphael Gobat (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile) and colleagues draw together current approaches to the question and develop a modeling technique based on our assumptions about galactic habitability and simulations of galaxy structure.

Panspermia is an ancient concept. Indeed, the word first emerges in the work of Anaxagoras (born ca. 500–480 BC) and makes its way through Lucian of Samosata (born around 125 AD), through Kepler’s Somnium, to re-emerge in 19th Century microbiology. Accidental propagation of life’s building blocks was considered by Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius in the early 20th Century. Fred Hoyle and Nalin Chandra Wickramasinghe developed the idea still further in the 1970s and 80s.

So how do we approach a subject that has remained controversial, likely because it does not appear necessary in explaining how life emerged on our own Earth? As the paper notes, modern work falls into three distinct categories, the first involving whether or not microorganisms can survive ejection from a planetary surface and re-entry onto another. Remarkably, hypervelocity impacts are not show-stoppers for the idea, suggesting that a small fraction of spores could survive impact and transit.

As to timescale and kinds of transfer mechanisms, most work seems to have focused on mass transfer between planets in the same stellar system, usually through lithopanspermia, which is the exchange of meteoroids. It’s true, however, that transit between different stars has been investigated, looking at radiation pressure on small grains of material. There are even a few studies on whether or not a stellar system might be intentionally seeded by means of technology. The term here is directed panspermia, a subject more often treated in science fiction than academic circles.

Although not entirely. While directed panspermia is off the table for Gobat and colleagues, we’ll take a look in a month or so at what does appear in the literature. Some interesting ideas have emerged, but they’re not for today.

What Gobat and co-authors have in mind is to apply a model of galactic habitability they have developed (citation below) in conjunction with the simulations of spiral galaxies based on hydrodynamics that are found in the McMaster Unbiased Galaxy Simulations (MUGS), a set of 16 simulated galaxies developed within the last decade. On the latter, the paper notes:

These simulations made use of the cosmological zoom method, which seeks to focus computational effort into a region of interest, while maintaining enough of the surrounding large-scale structure to produce a realistic assembly history. To accomplish this, the simulation was first carried out at low resolution using N-body physics only. Dark matter halos were then identified, and a sample of interesting objects selected. The particles making up, and surrounding, these halos were then traced back to their origin, and the simulation carried out again with the region of interest simulated at higher resolution.

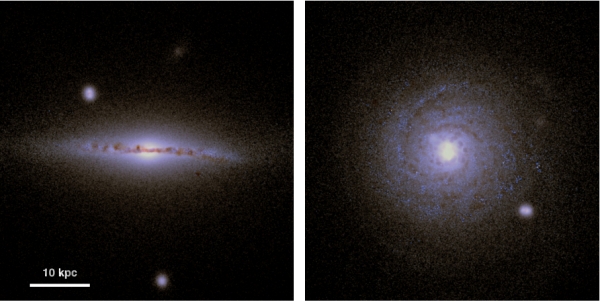

Simulation and re-simulation allow the MUGS galaxies to reproduce the known metallicity gradients in observed galaxies and likewise reproduce their large-scale structure, including disks, halos and bulges. The authors use one of the simulated galaxies, a spiral galaxy similar to but not identical with the Milky Way, to investigate the probability and efficiency of panspermia as dependent on the galactic environment.

Image: This is Figure 1 from the paper. Caption: Mock UV J color images of the simulated galaxy g15784 (Stinson et al. 2010; Nickerson et al. 2013), for both edge-on (left) and face-on (right) orientations, using star and gas particles, and assuming Bruzual & Charlot (2003) stellar population models and a simple dust attenuation model (Li & Draine 2001) with a gas-to-dust ratio of 0.01 at solar metallicity. Additionally, we include line emission from star particles with ages ? 50 Myr, following case B recombination (Osterbrock & Ferland 2006) and metallicity-dependent line ratios (Anders & Fritze-v. Alvensleben 2003). All panels are 50 kpc across and have a resolution of 100 pc. Two spheroidal satellites can be seen above and below the galactic plane, respectively. Credit: Gobat et al.

Panspermia appears to be more likely in the central regions of the galactic bulge, as we might assume due to the high density of stars there, a factor which counterbalances their lower habitability in this model. Panspermia is found to be much less likely as we move out into the central disk. In the model of habitability as developed by Gopat and Sungwook Hong in 2016, habitability increases as we depart from galactic center, while the new paper shows that the likelihood of panspermia works inversely, being more likely toward the bulge.

In a sense, we decouple habitability from panspermia. The paper uses the term ‘particles’ to refer not to individual stars, but to ensembles of stars with a range of masses but the same metallicity. This reflects, say the authors, the resolution limits of the simulations, which cannot track individual stars through time. From the paper, noting the narrow dynamic range of habitability vs. panspermia [the italics are mine]:

In dense regions [of the simulated galaxy], many source particles can contribute to panspermia, whereas in the outer disk and halo the panspermia probability is typically dominated by one or, at most, a few source star particles. Unlike natural habitability, whose value varies by only ? 5% throughout the galaxy, the panspermia probability has a wide dynamic range of several orders of magnitudes..

The models used here have a number of limitations, but it’s interesting that they point to panspermia as being considerably less efficient at seeding planets than the evolution of life on the planets themselves. At best, the authors find the probability of panspermia to be no more than 3% of all the star particles in their simulation. This may be an overly generous figure, and the paper acknowledges that it cannot be more precisely quantified other than to say that when it comes to efficiency, local evolution wins going away. Higher resolution galaxy simulations will offer more realistic insights.

We have a result, as the authors acknowledge, that is more qualitative than quantitative, a measure of how much we have to learn about galaxies themselves, and about the Milky Way in particular. The sample galaxy, for example, has a higher bulge-to-disk ratio than the Milky Way. But more significantly, the capture fraction of spores by target planets and the likelihood that life actually does develop on planets considered habitable are subjects with no concrete data to firm up the conclusions.

We can anticipate that future simulations will take into account a rotating evolving galaxy as opposed to the single simulation ‘snapshot’ the paper offers. Nonetheless, this modeling of organic compounds being transferred between stars points to the orders of magnitude difference in the likelihood of panspermia between the inner and the outer disk, a useful finding. Given that so few of the star particles the simulation generates have high panspermia probability, the process may occur but under conditions that make it much less effective than prebiotic evolution.

The paper is Gobat et al., “Panspermia in a Milky Way-like Galaxy,” accepted at the Astrophysical Journal (preprint). The paper on galactic habitability is Gobat & Hong, “Evolution of galaxy habitability,” Astronomy & Astrophysics Vol. 592, A96 (04 August 2016). Abstract.