Do technological cultures survive their growing pains? Species extinction through war or unintended environmental consequences — a cap upon the growth of civilizations — could be one solution to the Fermi question. They’re not here because they’re not there, having left ruined cities and devastated planets in their wake, just as we will. It’s a stark picture whether true or not, one that makes us ponder how the things we do with technology affect our future. Consider the question in terms of time.

The Holocene epoch, in which we live, began about 10,000 BC, incorporating early periods of human technology back to the rise of farming amd the growing use of metals. And while there has been scant time for true evolutionary change in animal and plant life during this short period, it is certainly true that extinctions of many large animals as we move from the late Pleistocene into the early Holocene have not only changed the world through which humans moved but may have been at least partially caused by human activities. Symbolic of the process are mammoths, mastodons, as well as giant sloths and saber-toothed tigers.

Even so, until recently recorded history human actions had not fundamentally changed gloabl environmental conditions. How much of an effect has our species had on the planet, and is that effect now different enough to change our terminology? Geologists at the University of Leicester, picking up on a proposal first made by chemist Paul Crutzen in 2002, now suggest that the Holocene epoch has ended. The new epoch, which they dub the Anthropocene, is the result of significant human actions. Its markers include disturbances to the carbon cycle and global termperature, ocean acidification, changes to sediment erosion and deposition, and species extinctions like those mentioned above.

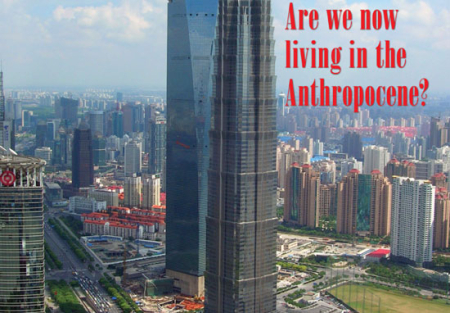

The Anthropocene formally recognizes a widely perceived reality, the sharp line between the pre-industrial world and the technology-laden planet we now call home, awash with digital tools and freighted with the after-effects of industrial activity. And indeed, the cover of GSA Today (a publication of the Geological Society of America) in which this work appears makes the case rather strongly, showing the high-rise buildings of Shanghai fading out into the distance. It’s a stark reminder of how megacities like this one are transforming the planet.

Image credit: Geological Society of America.

But how do you choose a marker for the onset of an epoch? Specialists call such a marker a Global Stratigraphic Section and Point, or GSSP. With China and India in the midst of their own industrial revolutions, homing in solely on Western history may not be accurate. C02 levels could be helpful, but global changes in their levels are gradual. The authors’ musing takes in a range of possibilities:

From a practical viewpoint, a globally identifiable level is provided by the global spread of radioactive isotopes created by the atomic bomb tests of the 1960s; however, this postdates the major inflection in global human activity. Perhaps the best stratigraphic marker near the beginning of the nineteenth century has a natural cause: the eruption of Mount Tambora in April 1815, which produced the “year without a summer” in the Northern Hemisphere and left a marked aerosol sulfate “spike” in ice layers in both Greenland and Antarctica and a distinct signal in the dendrochronological record…

Or perhaps, the paper continues, picking a marker at this level of detail is not necessary, as long as the realities of what Paul Crutzen argued in 2002 are acknowledged. The current global environment is dominated by human activity to the point where reconsideration of our terminology must take it into account. The rapid rise of population from the beginning of the industrial revolution in Europe and the exploitation of coal, oil and gas have fueled a planetary transformation. And note this:

The combination of extinctions, global species migrations…, and the widespread replacement of natural vegetation with agricultural monocultures is producing a distinctive contemporary biostratigraphic signal. These effects are permanent, as future evolution will take place from surviving (and frequently anthropogenically relocated) stocks.

A new epoch indeed, the case for which is made powerfully in this paper. The assumption here is that this inevitable transformation is survivable, but then Centauri Dreams is sometimes accused of excess optimism. The reference is Zalasiewicz et al., “Are we now living in the Anthropocene,” GSA Today Vol. 18, Issue 2 (February 2008), pp. 4-8 (abstract).

Hi Folks;

I would like to think that many ETI civilizations survive to develope interstellar travel as I hope we will. Even with our known, proven, and industrially widespread physics in commerce and in R&D, we seemed poised to be able to travel to the stars.

As we are all aware, concepts such as: fusion rockets, effecient fusion reactor powered electron and ion rockets, magnetoplasmahydrodynamic drives, electroplasmahydrodynamic drives electromagnetoplasmahydrodynamic drives, photon rockets, dive and fry solar and stellar sails, beamed electromagnetic sails and photovoltaic or optical thermal electrical propulsion systems, beamed mass drive for momentum transfer or for fueling the space craft with fusion or antmatter fuel, fusion runway based propulsion, magnetic field effect propulsion, any practical and improved interstellar ramjet systems, matter/antimatter rockets and matter/antimatter reaction powered electrical propulsion systems, effeicient and optimized magsail propulsion and the like; can probably get us to the stars.

Some of the above ordinary physics based schemes when highly optimized could lead us to very high gamma factors allowing us to travel about the Milky Way in one human generation ship time. Good old fashioned nuclear and proven particle physics, special relativity, quantum mechanics, classical electrodynamics, modern materials science, modern computational control of flight path and surviellance for collision aviodance, laser and particle beams, and the like can lead us there.

To almost all of the Tau Zero readership, all of these technologies and related concepts seem obvious and that is part of the reason why they are becomming well enough understood to become reality within the comming decades. All we need is money and the political will do carry out such missions. By the same token, I am haunted at some level by the Cold War images of large cities being vaporized by a single high yield nuclear detonation in popular movies and the plots of the science fiction movies such as the original “Planet of the Apes” series. One thing is certain, this is a very critical next half century for us. The stakes have never been so high, the potential rewards and opportuinities have never been so great.

Thanks;

Your Friend Jim

Hi Jim & All

Perhaps the Anthropocene could be dated from the arrival of humans in some part of the world other than Eurasia? They reached Australasia c. 50 kya and a major extinction followed. Or North America c. 15 kya, followed by the putative cometary catastrophe c. 13 kya.

I agree with Jim on the importance of now. I do wonder if we’ll propagate a humane and decent society into indefinite futurity, or lapse into a new and probably interminable Dark Age. But also possible is some kind of Singular transition which will make our “Anthropocene” seem as narrow in time as the K/T event. Who knows what the post-Human era may bring…

I’m not sure of how good a concept the “Anthropocene” is… see some other blogs have quite good arguments against this view (in the case of Greg Laden’s blog, even that the Holocene is not really that strong a concept).

Bear in mind that the Chicxulub impact was only a transition, despite leaving a layer of iridium behind… similarly the human-caused changes may be another dramatic event, rather than a sign of a new geological period. Whether humans will continue to dominate the coming millions of years on this planet, who knows?

Greg Laden is also interesting on the problem of scale: “Geological periods are defined by changes that can not only be viewed from a great distance in time, but can’t be missed from so far away. It should be as reasonable to define a geological epoch as it is to note the existence of a mountain chain from many kilometers away. It might be that anthropogenic changes to the biota and the landscape are sufficiently blatant and long lasting to create a such a distinct distance, or they may not. The Holocene itself is invalid because it is too near-sighted (in time) of a concept, considering a mere several thousand years and calling it a distinct period. And we (well, they, I wan’t even born yet) got that totally wrong. How does a few centuries of observation translate into a valid geological periodization? It does not. It is possible that we can define a new period that begins about now (plus or minus in geological time). But those proposing the Anthropocene are several million years premature. They need to be more patient.”

Interesting stuff, and a useful counter-view:

http://scienceblogs.com/gregladen/2008/01/are_we_in_the_anthropocene_no.php

Then there’s the view that the ‘anthropocene’ should be considered to start with the development of agriculture. William Ruddiman has proposed that clearing forests for agriculture has kept CO2 levels up & rice farming has kept methane levels up for the past several millennia & without this the next glacial period would already be starting. See the March 2005 Scientific American.

Even without Ruddiman’s hypothesis agriculture is when humans have a really major influence on the landscape.

I have to agree with Paul here, there simply isn’t enough elapsed time.

But what if a hard-core Technological Singularity occurred? One in which a super-evolving AI decided to make the planet into computronium?

Highly unlikely, but a good thought experiment about rapid geological change.

jim just read your latest remarks and yes there are alot of ways to potentially get to the stars.i just hope we survive long enough to develop one or two of them! no kidding.gosh every day i see “roadside bomb kills 5 more gi’s or bomb kills 3 dozen in arab market”!!!!!!!! excuse the poor english please but – DON’T LOOK GOOD !!! thank you very much your friend george

Then there would be no more geology, and thus no requirement for geological periods :)

Singularity lite: one to two levels of faster technological change

The technological singularity is a hypothesized point in

the future variously characterized by the technological

creation of self-improving intelligence, unprecedentedly

rapid technological progress, or some combination of

the two.

I would want to focus on the aspect of “unprecendentedly

rapid technological progress”. I feel that a proxy for measuring

“technological progress” can be the rate of human or world

GDP growth (gross domestic product) or economic growth.

Money represents a near universal medium of exchange.

You can change money for goods and services. Therefore,

it is a proxy for increasing value and progress.

Economic growth would in general mean positive technological

change. Faster growth would be faster technological change.

Full article here:

http://nextbigfuture.com/2008/02/singularity-lite-one-to-two-levels-of_01.html

Then there would be no more geology, and thus no requirement for geological periods

Okay, I’ll go with that. But wouldn’t a created VR “geological” epoch occur in the computronium by our “damned offspring”?

Economic growth would in general mean positive technological

change. Faster growth would be faster technological change.

Sure. But wouldn’t it evolve away from traditional economics into something author Charles Stross calls “Economics 2.0”? Whereby actual contracts, programs, currency and other aspects of Economics 1.0 become intelligent entities in their own right and human interaction is no longer required?

I think I am getting a little tired of all the’pooh-pooh!! When do we say “enough is enough?? First of all, this tiny planet was not designed for 6 billion people. Just blame it all on” Cow’s Fartting”.. Our useable atmosphere is only 7 miles deep. We just CAN’T keep pumping crap into our air! Especialy if we keep stroying the filters!! Trees fall at a greater rate every year. I’m not a tree hugger, but, I can see what’s taking place around me. Don’t worry about the bomb,boys, we are gonna’ procreate ourselves to extinction!!

Team Uncovers New Evidence of Recent Human Evolution

ScienceNOW Daily News Feb. 4, 2008

*************************

French and Spanish researchers have

found new evidence to support recent

evolution in humans: genes for

traits such as skin color and

stature changed rapidly to allow

humans to survive in new habitats.

The team identified 582 genes that

have evolved differently in

different populations in the past

60,000 years, including a dozen that

protect…

http://www.kurzweilai.net/email/newsRedirect.html?newsID=7956&m=25748

Can the Singularity Save Us From Ourselves?

To quote:

Persons who believe firmly in the inevitability of The Singularity might be surprised to learn that the default human society is the closed society, resistant to change. Most of them have never known anything but open societies, born of western civilisation’s restless urge to expand intellectual horizons. They live in an exceptional time, in an exceptional society, yet somehow believe it to be the human default. That type of blindness comes from forgetting to study history.

Full article here:

http://alfin2100.blogspot.com/2008/05/can-singularity-save-us-from-ourselves.html

Is the City an “Organism” Operating Beyond the Bounds of Biology?

For the first time in history, the majority of the people on our planet live in cities. Going forward, human history will become urban history: homo sapiens has evolved into homo urbanus.

The back story for this profound if not evolutionary shift in human behavior is that fact even in 1800 only 3% of the world’s population lived in cities.

Dr. Geoffrey West, President and Distinguished Professor of the Santa Fe Institute, led a team of scientists that has found that city growth driven by wealth creation increases at a rate that is faster than exponential. The only way to avoid collapse as a population outstrips the finite resources available to it is through constant cycles of innovation, which re-engineer the initial conditions of growth. But the greater the absolute population, the smaller the relative return on each such investment, so innovation must come ever faster.

Full article here:

http://www.dailygalaxy.com/my_weblog/2008/06/is-the-human-ci.html

http://www.dailygalaxy.com/my_weblog/2008/11/did-the-planets.html

November 04, 2008

Did The Planet’s Tectonics Trigger Human Evolution?

“Tectonics was ultimately responsible for the evolution of humankind.”

Royhan and Nahid Gani of the University of Utah, Energy and Geoscience Institute.

The scientists argue that the “Wall of Africa” – an accelerated uplift of mountains and highlands stretching from Ethiopia to South Africa- blocked much ocean moisture, converting lush tropical forests into an arid patchwork of woodlands and savannah grasslands that gradually favored human ancestors who came down from the trees and started walking on two feet – an energy-efficient way to search larger areas for food in an arid environment.

The East African Rift runs about 3,700 miles from the Ethiopian Plateau south-southwest to South Africa’s Karoo Plateau. It is up to 370 miles wide and includes mountains reaching a maximum elevation of about 19,340 feet at Mount Kilimanjaro.

The rift “is characterized by volcanic peaks, plateaus, valleys and large basins and freshwater lakes,” including sites where many fossils of early humans and their ancestors have been found, says Nahid Gani (pronounced nah-heed go-knee), a research scientist. There was some uplift in East Africa as early as 40 million years ago, but “most of these topographic features developed between 7 million and 2 million years ago.”

“Because of the crustal movement or tectonism in East Africa, the landscape drastically changed over the last 7 million years,” says Royhan Gani (pronounced rye-hawn Go-knee). “That landscape controlled climate on a local to regional scale. That climate change spurred human ancestors to evolve from apes.”

Hominins – the new scientific word for humans (Homo) and their ancestors (including Ardipithecus, Paranthropus and Australopithecus) – split from apes on the evolutionary tree roughly 7 million to 4 million years ago. Royhan Gani says the earliest undisputed hominin was Ardipithecus ramidus 4.4 million years ago. The earliest Homo arose 2.5 million years ago, and our species, Homo sapiens, almost 200,000 years ago.

Plate Tectonics – movements of Earth’s crust, including its ever-shifting tectonic plates and the creation of mountains, valleys and ocean basins – has been discussed since at least 1983 as an influence on human evolution.

But much of the previous debate of how climate affected human evolution involves global climate changes, such as those caused by cyclic changes in Earth’s orbit around the sun, and not local and regional climate changes caused by East Africa’s rising landscape.

“Although the Wall of Africa started to form around 30 million years ago, recent studies show most of the uplift occurred between 7 million and 2 million years ago, just about when hominins split off from African apes, developed bipedalism and evolved bigger brains,” the Ganis write.

“Nature built this wall, and then humans could evolve, walk tall and think big,” says Royhan Gani. “Is there any characteristic feature of the wall that drove human evolution?”

“Clearly, the Wall of Africa grew to be a prominent elevated feature over the last 7 million years, thereby playing a prominent role in East African aridification by wringing moisture out of monsoonal air moving across the region,” the Ganis write. That period coincides with evolution of human ancestors in the area.

Royhan Gani says the earliest undisputed evidence of true bipedalism (as opposed to knuckle-dragging by apes) is 4.1 million years ago in Australopithecus anamensis, but some believe the trait existed as early as 6 million to 7 million years ago.

The Ganis speculate that the shaping of varied landscapes by tectonic forces – lake basins, valleys, mountains, grasslands, woodlands – “could also be responsible, at a later stage, for hominins developing a bigger brain as a way to cope with these extremely variable and changing landscapes” in which they had to find food and survive predators.

For now, Royhan Gani acknowledges the lack of more precise timeframes makes it difficult to link specific tectonic events to the development of upright walking, bigger brains and other key steps in human evolution.

“But it all happened within the right time period,” he says. “Now we need to nail it down.”

Posted by Casey Kazan.

http://unews.utah.edu/p/?r=121207-1

Are We Organisms Or Living Ecosystems?

Seed April 14, 2009

*************************

There’s a growing consensus among scientists that the relationship between us and the 100 trillion bacterial microbes in our bodies (outnumbering our human cells 10 to one) is a two-way street….

http://www.kurzweilai.net/email/newsRedirect.html?newsID=10435&m=25748

Humanity close to passing the Hofstadter-Turing Test?

A version of the Turing Test now running in Second Life could one day prove that humanity is truly intelligent

Monday, April 27, 2009

Various versions of the Turing test have been put forward over the years but only one is so tough that even humans haven’t yet passed it. That will change if Florentin Neumann at the University of Paderborn in Germany and a couple of pals have their way.

This alternate exam is called the Hofstadter-Turing Test, after Douglas Hofstadter who put forward a version of the idea in an essay called Coffee House Conversation in 1982. Here’s how it works (pay attention because it contains a certain circularity to the argument):

An entity passes the Hofstadter-Turing Test if it first creates a virtual reality, then creates a computer program within that reality which must finally recognise itself as an entity within this virtual environment by passing the Hofstadter-Turing Test.

Spot the tricky circularity to this test? Players can only pass if they create a virtual intelligence which must then pass the test itself. And since that hasn’t been achieved by any human in history, nobody has yet passed.

What’s interesting about the paper though, is that Neumann and co claim that humanity is moving closer to achieving a pass. First of all, we’re half way there because we’ve already built various virtual worlds. And now Neumann and co claim to have implemented a version of the Hofstadter-Turing Test in the Second Life virtual world.

Full article here:

http://www.technologyreview.com/blog/arxiv/23444/

A thermodynamic limit on brain size

Posted: 25 May 2009 09:10 PM PDT

If our brains have to be cooled like computer chips, is there a limit on how big they can be?

In recent years, chip makers have conlcuded that the race to produce ever faster circuits is a fool’s game. As the clock speed increases, the amount of energy lost as heat becomes too large to dissipate efficiently and in any case, the waste is unjustifiable.

That raises some interesting questions about the human brain, says Jan Karbowski at the Sloan-Swartz Center for Theoretical Neurobiology at the California Institute of Technology. Karbowski points out that the problem of heat transfer could be a serious factor shaping brain evolution and so has embarked on a program to determine the relationship between brain temperature, its size, cerebral power generated and neural activity.

The question on Karbowski’s mind is whether there is any thermodynamic limit on brain size. And if so, does 5 kg, which Karbowski says is the mass of the largest mammalian brain, approach that limit?

Karbowski points out that brain cooling is not a classic problem of surface-area to volume. Instead, brain cooling is more closely comparable to that in a combustion heat engine where a liquid coolant removes heat.

“In the brain, the role of the coolant is played by the cerebral blood, but only in the deep region because there blood has a slightly lower temperature than the brain tissue,” says Karbowski.

But in the regions closer to the surface, it is the oter way round: brain tissue is colder than the cerebral blood which warms the brain.

This implies that the thermodynamics of heat balance does not restrict the brain size. And this in turn suggests that brains could be heavier than 5 kg, says Karbowski.

(And of course they do get bigger than this. The sperm whale’s brain can be 9 kilograms).

That leaves plenty of growing room for humans which have brains of only 1.5 kilograms on average.

Ref: http://arxiv.org/abs/0905.3690: Thermodynamic Constraints on Neural Dimensions, Firing Rates, Brain Temperature and Size

How Close We Live and Work and How We Move Has Large Effects on Human Behavior

1. Increasing population density, rather than boosts in human brain power, appears to have catalysed the emergence of modern human behaviour, according to a new study by UCL (University College London) scientists published in the journal Science. High population density leads to greater exchange of ideas and skills and prevents the loss of new innovations. It is this skill maintenance, combined with a greater probability of useful innovations, that led to modern human behaviour appearing at different times in different parts of the world.

This work further emphasizes the importance of cluster development of economic development.

http://nextbigfuture.com/2009/06/how-close-we-live-and-work-and-how-we.html

i believe the climate is still to warm to say the Holocene has ended as much of the data reveals that the earth has to a major majority been mostly very cold,and it cannot be denied that we are heading for a cold epoch

i still find it very annoying that the governments of the world have continually lied about the true cause of c 02,so they can justify the hefty tax duties under the misleading guise of global warming.This warming period is just the upward spike in a very spiky graph if you look at the data from the last 5000 years .They should tell the truth and explain to the public that the worlds oceans are releasing vast amounts of c o2 at this present time as they have always done so just before the cold period is entered.i would urge everyone not to beleive the political spin ,but to go have a look at reliable scientific data ,much of which is based on ice core samples,these samples cannot lie,and the deeper you drill the further back in time you go.the amounts we humans have contributed is insignificant compaired to what the worlds oceans hold……but,,there,s money to be made from global warming……………..right !!

Natural forces always determine what happens in physical operations. This is the most fundamental law and it has been in control throughout evolution of life and systems on this planet. It is just as applicable now to the systems of industrial civilization as it was before humans had any impact on what happens. Humans have made decisions about systems to utilize some of these natural forces to construct, operate and maintain the temporary edifice of civilization by using up the limited usable natural resources, including the fossil fuels. This is an unsustainable process. Anthropocene epoch will be but a blip on the evolutionary time scale.