Before getting into the distant regions near Pluto/Charon, let’s pause for a moment with a reflection on speed. New Horizons left Earth orbit traveling faster than any other vehicle launched into interplanetary space, although it has since slowed. Now the Juno mission is getting press for its velocity, perhaps impelled by this quote from Bill Knuth (University of Iowa), who is lead investigator for one of the probe’s nine scientific instruments. Of Juno’s recent close approach to Earth, Knuth says:

“Juno will be really smoking as it passes Earth at a speed of about 25 miles per second relative to the Sun. But it will need every bit of this speed to get to Jupiter for its July 4, 2016, capture into polar orbit about Jupiter. The first half of its journey has been simply to set up this gravity assist with Earth.”

The speed is impressive, about 40 kilometers per second, and far above Voyager 1’s 17.1 kilometers per second, as well as New Horizons’ expected 14 kilometers per second at the Pluto/Charon flyby in 2015 — after its sizzling departure, New Horizons has been slowing as it climbs out of the Sun’s gravity well. Juno has been pegged in some press reports as ‘the fastest man-made object ever,’ but its 40 kilometers per second doesn’t stand up to the two Helios probes, launched like Voyager back in the 1970s, which actually claim that title at 70 kilometers per second. Keep your eyes on the upcoming Solar Probe Plus for even faster velocities.

Amidst the Plutonian Moons

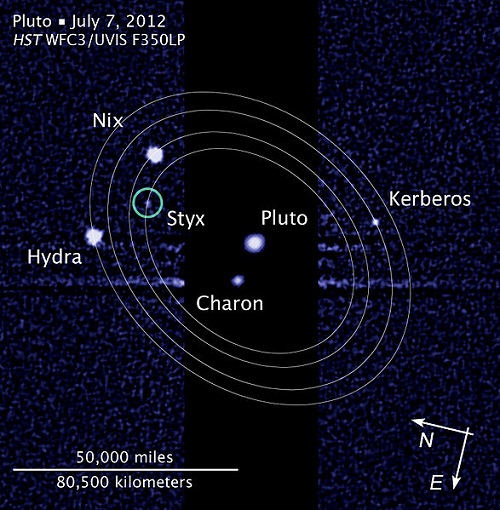

But back to Pluto/Charon, as I catch up with news from the AAS Division for Planetary Sciences meeting earlier this month in Denver. One of the curiosities about Pluto as we’ve discovered new moons there is their arrangement. Charon is the nearest and by far the largest moon, but what we see in the others is a steady succession that varies with Charon’s own orbital period. Thus Styx, Nix, Kereberos and Hydra present us with orbital periods that are 3, 4, 5 and 6 times longer than Charon’s own. That flies in the face of current models of formation of such moons, a situation that, according to Southwest Research Institute scientist Hal Levison, “suggests that we have been missing some important mechanism to transport material around in this system.”

Image: A Hubble image of Pluto and its moons that has been modified by replacing “P4” and “P5” with the newer designations “Kerberos” and “Styx” respectively. Credit: NASA/Wikimedia Commons.

The SwRI study, described in this news release, modeled Charon itself by assuming a large impact in the early system, with additional moons built out of debris from this and other presumed collisions. Charon is fully one-tenth the mass of Pluto (by comparison, the Moon is 1/81 the mass of Earth), and its effect on early moon formation would be profound. Small moons that approached it would be flung outward while other small moons would collide, a series of early catastrophes that would lead to moon-building materials being pushed outward.

“The implications for this result are that the current small satellites are the last generation of many previous generations of satellites,” said Dr. Kevin Walsh, another investigator and a research scientist in SwRI’s Planetary Science Directorate at Boulder, Colo. “They were probably first formed around 4 billion years ago, and after an eventful million years of breaking and rebuilding, have survived in their current configuration ever since.”

All of which leads me to the New Horizons Message Initiative that was first announced at the 100 Year Starship Symposium in Houston not long ago. If you haven’t signed the NHMI petition yet, please visit the site and do so. The plan is to reconfigure a small portion of New Horizons’ computer memory, once its mission has been accomplished at Pluto/Charon and any Kuiper Belt objects beyond, so we can upload a message from humanity that will be crowd-sourced from all over the world. This is a private initiative and we need petition signatures to persuade NASA to consider this follow-up to the original Voyager ‘golden records.’ The NHMI is being developed through the capable work of Jon Lomberg and a team of volunteers. Lomberg’s work with Frank Drake in designing the cover for the Voyager records helped us gain perspective on our place in the cosmos as we reflected on what sights and sounds best represent our species.

It is a good thing that the moons are in resonance orbits with Charon. This may mean there are not a large number of boulders orbiting Pluto that could endanger the probe in 2015.

New Horizons Message Initiative Hopes To Send Self-Portrait Of Humanity To The Stars

By Mike Killian

AmericaSpace – October 15, 2013

To date, all four of the spacecraft NASA has blasted into the unknown depths of the outer solar system have carried some kind of message from Earth to the stars. Pioneers 10 and 11, as well as Voyager 1 and 2 all carry an interstellar message from mankind, intended for any extraterrestrial traveler who may someday find them.

However, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, which is currently three billion miles away from Earth en route to Pluto, does not, and a new campaign is underway to change that. [The final rocket stages of all five deep space probes also lacked any information packages, please note.]

“Like the Voyager Record, this will be both a message from Earth and a message to Earth,” said Project Director for the New Horizons Message Initiative Jon Lomberg, who also served as the Design Director for NASA’s famous Voyager Golden Record.

Lomberg is regarded as Earth’s most experienced creator of space message artifacts, and was Carl Sagan’s most frequent artistic collaborator.

“The very act of creating it will be a powerful reminder that we all share a common heritage and future on this ‘pale blue dot’ we call Earth.”

Full article here:

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=43972

I think it should be pointed out ( I have not read the paper yet) that the earth moon impact formation theory and any post/secondary moon formation at Pluto theory should take into account the much slower sun centrist orbital speeds out near Pluto.

I wonder if Robin Cunops theory’s of gas giant moon formation can be modified by this?

like the, “flight of the dragon fly’s” Flowen I form a rock and sink into the lagoon to think of this idea some more……………

ok I have unrocked like the flowen in flight of the dragon fly;

A gas giant forms in a solar system but a little bit further out then the NICE model, slower orbital speeds further out do allow orbital dynamics to capture larger objects such as earth size objects that Robin Cunops in place gas giant moon formation models allow for.

gas giant and exomoons migrate back in……( near star encounter?)

except we have do a trade; the further out we go the chances of this capture of such a large object increases and,

how do we migrate this system into the HBZ

my advanced degree brother hates me for bring up these RARE EARTH hypothesis, some of you have to :)

he needs to join the flowen from the ” flight of the dragon fly” and “rock up” sometimes :):)

my rock up experience has not deterred me from Robin Canup,earth size exomoons will always be very rare, captured earth sized objects even more rare sigh I am sad………….I want to envision exomoons with magnetosphere and metozoen life