Images of distant exoplanets, once only a wish for future space missions, have begun to turn up with a certain regularity. The three planets around HR8799 and the single gas giant around Fomalhaut were announced on the same day, while a week later we once again have Beta Pictoris in focus, a young star so well studied that images of its dust disk go back to the mid-1980s. A new analysis of 2003 data from the Very Large Telescope now brings a team of French astronomers to offer a probable — but not certain — image of what may turn out to be Beta Pictoris b.

The observations seem to show a gas giant some eight times more massive than Jupiter, orbiting at roughly 8 AU, not far inside Saturn’s orbit in our own Solar System. But astronomer Gael Chauvin (Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de l’Observatoire de Grenoble) is quick to qualify the finding:

“We cannot yet rule out definitively, however, that the candidate companion could be a foreground or background object. To eliminate this very small possibility, we will need to make new observations that confirm the nature of the discovery.”

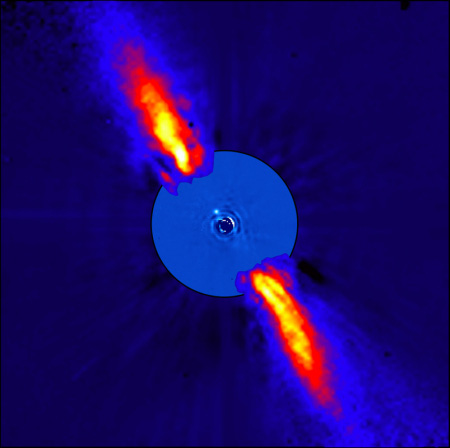

Image: This composite image represents the close environment of Beta Pictoris as seen in near infrared light. This very faint environment is revealed after a careful subtraction of the much brighter stellar halo. The outer part of the image shows the reflected light on the dust disc, as observed in 1996 with the ADONIS instrument on ESO’s 3.6 m telescope; the inner part is the innermost part of the system, as seen at 3.6 microns with NACO on the Very Large Telescope. The newly detected source is more than 1000 times fainter than Beta Pictoris, aligned with the disc, at a projected distance of 8 times the Earth-Sun distance. Because the planet is very young, it is still hot, with a temperature around 1200 degrees C. Both parts of the image were obtained on ESO telescopes equipped with adaptive optics. Credit: ESO/A.-M. Lagrange et al.

Take note of this in the above statement: The source is more than 1000 times fainter than Beta Pictoris — remember that this is at infrared wavelengths, where the contrast between the primary and candidate planet is minimized. A look at this same system in visible light would come up short, as the star’s glare would drown out any planetary signature.

That ‘small possibility’ of a spurious identification seems even smaller when you consider that an examination of Hubble archives turned up nothing by way of a foreground or background object. Moreover, the candidate object is in the plane of the disk, with the right mass and distance to meld with what we’ve already learned about this well studied environment. Beta Pictoris b would be closer than any planet we’ve found via direct imaging, an object bright in the infrared around a young star (12 million years old) that is still growing its planetary system. Refining our detection methods for cooler and older planets should widen the field of directly imaged worlds and offer new data on planetary formation.

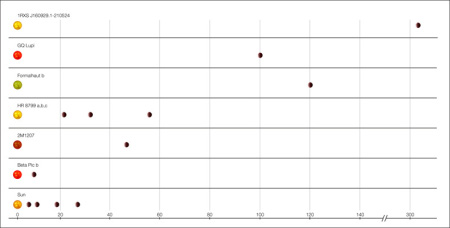

Here’s a chart showing candidate planetary systems that have been imaged to this point (you’ll need to click to enlarge):

Image: This diagram compares the various candidate planetary systems that have been imaged with our own Solar System. Indicated are the star and the position of the candidate planets. The probable planet around Beta Pictoris is the closest to its host star of all extra-solar planets yet imaged, and is comparable to Saturn as far as its distance is concerned. The scale is the distance between the Earth and the Sun. A list of all candidate exoplanets directly imaged can be found at here. Credit: ESO

I don’t see the paper up on the arXiv server yet, but look here for a preprint. Submitted to Astronomy & Astrophysics, it’s Lagrange et al., “A probable giant planet imaged in the ? Pictoris disk. VLT/NACO Deep L-band imaging.”

I’m unsure HST could actually detect it if it were a background star anyway. This image is the best I know of of Bet Pic from HST.

http://i159.photobucket.com/albums/t137/CrossingStyx/Astronomy/disk.jpg

HST’s occultation disk blocks out the region were the planet would be.

The extra solar catalog gives the following stats. for beta Pic b: mass = 8mJ, period=16days, semi major axis=8AU. It seems that if the semi major axis of this planet is 8AU, it’s orbital period cannot be as short as 8days?????

Yeah, the EPE is wrong. Jean Schneider got days and years mixed up apparently.

Yes, it has to be a typo. The orbital period should be of the order of a couple of decades with that semi-major axis

A typo indeed. The Lagrange paper cites an orbital period of roughly 16 years.

Is the companion supposed to be visible in the image to this paper? If so, where?

Jean Schneider just wrote to confirm that this was a typo in the catalog — the orbital period is indeed around sixteen years.

djlactin: Look at about the 11 o’clock position just above the center of the image.

Interesting that the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia lists this one as “confirmed”… not sure it really warrants that status yet: until orbital motion is detected, it’s more “very plausible”. Note also that the 16 years period assumes the planet has semimajor axis 8 AU. However this is only the projected separation, the true semimajor axis may be somewhat different (note that the predictions from modelling the disk structure suggested the planet’s orbit is ~12 AU, which would still be consistent with the observed separation)

As is mentioned in the paper, an independent mass measurement of the planet would be very useful in constraining models of giant planet evolution. This may lead to improved mass determinations of the other imaged planets.

Is the rotation direction known? (e.g. of the disk, assuming that the planet rotates in the same direction)

Will the planet next go behind the star or pass in front?

Would be nice if it separates more in the next years.

According to this paper, the NE extension of the dust disk is moving away from us and the SW extension is moving towards us. Since the planet was detected NE of Beta Pictoris, if it is revolving in the same direction as the dust disk it will be passing behind the star.

So it could get brighter before it disappears in the star’s glare as it is approaching the ‘full’ phase. Maybe not so bad at all.

Thanks for finding it.

this is a interest discovery of circumbinary planets around HW vir two planet its been discovery on this system,

http://arxiv.org/PS_cache/arxiv/pdf/0811/0811.3807v1.pdf

and

http://exoplanet.eu/star.php?st=HW+Vir#a_publi

would be amazing see this two suns arise on horizon of hypothetic moon around of one of this planets,. fascinating indeed

Is Beta Pic b the transiting planet of November 1981?

Authors: A. Lecavelier des Etangs, A. Vidal-Madjar

(Submitted on 5 Mar 2009)

Abstract: In 1981, Beta Pictoris showed strong and rapid photometric variations that were attributed to the transit of a giant comet or a planet orbiting at several AUs (Lecavelier des Etangs et al. 1994, 1995, 1997; Lamers et al. 1997).

Recently, a candidate planet has been identified by imagery in the circumstellar disk of Beta Pictoris (Lagrange et al. 2009). This planet, named Beta Pic b, is observed at a projected distance of 8AU from the central star. It is therefore a plausible candidate for the photometric event observed in 1981.

The coincidence of the observed position of the planet in November 2003 and the calculated position assuming that the 1981 transit is due to a planet orbiting at 8 AU is intriguing.

Assuming that the planet that is detected on the image is the same as the object transiting in November 1981, we estimate ranges of possible orbital distances and periods.

In the favored scenario, the planet orbits at about 8 AU and was seen close to its quadrature position in the 2003 images. In this case, most of the uncertainties are related to error bars on the position in 2003. Uncertainties related to the stellar mass and orbital eccentricity are also discussed.

We find a semi-major axis in the range [7.6-8.7] AU and an orbital period in the range [15.9-19.5] years. We give predictions for imaging observations at quadrature in the southwest branch of the disk in future years (2011-2015).

We also estimate possible dates for the next transits and anti-transits.

Comments: Accepted for publication in Astronomy and Astrophysics

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:0903.1101v1 [astro-ph.EP]

Submission history

From: Alain Lecavelier des Etangs [view email]

[v1] Thu, 5 Mar 2009 21:00:11 GMT (104kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0903.1101

Solar System Analogs Around IRAS-Discovered Debris Disks

Authors: Christine H. Chen, Patrick Sheehan, Dan M. Watson, P. Manoj Puravankara, Joan R. Najita

(Submitted on 19 Jun 2009)

Abstract: We have rereduced Spitzer IRS spectra and reanalyzed the SED’s of three nearby debris disks: lambda Boo, HD 139664, and HR 8799. We find that that the thermal emission from these objects is well modeled using two single temperature black body components.

For HR 8799 — with no silicate emission features despite a relatively hot inner dust component (Tgr = 150 K) — we infer the presence of an asteroid belt interior to and a Kuiper Belt exterior to the recently discovered orbiting planets.

For HD 139664, which has been imaged in scattered light, we infer the presence of strongly forward scattering grains, consistent with porous grains, if the cold, outer disk component generates both the observed scattered light and thermal emission.

Finally, careful analysis of the lambda Boo SED suggests that this system possesses a central clearing, indicating that selective accretion of solids onto the central star does not occur from a dusty disk.

Comments: 8 pages, 2 figures (including 2 color figures), ApJ, in press

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:0906.3744v1 [astro-ph.EP]

Submission history

From: Christine H. Chen [view email]

[v1] Fri, 19 Jun 2009 20:28:18 GMT (103kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0906.3744

Constraining the orbit of the possible companion to Beta Pictoris: New deep imaging observations

Authors: Anne-Marie Lagrange (LAOG), Markus Kasper (ESO), Anthony Boccaletti (LESIA), Gaël Chauvin (LAOG), Damien Gratadour (LESIA), Thierry Fusco, David Ehrenreich (LAOG), Daniel Apai (STSci), David Mouillet (LAOG), Daniel Rouan (LESIA)

(Submitted on 30 Jun 2009 (v1), last revised 1 Jul 2009 (this version, v2))

Abstract: We recently reported on the detection of a possible planetary-mass companion to Beta Pictoris at a projected separation of 8 AU from the star, using data taken in November 2003 with NaCo, the adaptive-optics system installed on the Very Large Telescope UT4.

Even though no second epoch detection was available, there are strong arguments to favor a gravitationally bound companion rather than a background object. If confirmed and located at a physical separation of 8 AU, this young, hot (~1500 K), massive Jovian companion (~8 Mjup) would be the closest planet to its star ever imaged, could be formed via core-accretion, and could explain the main morphological and dynamical properties of the dust disk.

Our goal was to return to Beta Pic five years later to obtain a second-epoch observation of the companion or, in case of a non-detection, constrain its orbit. Deep adaptive-optics L’-band direct images of Beta Pic and Ks-band Four-Quadrant-Phase-Mask (4QPM) coronagraphic images were recorded with NaCo in January and February 2009. We also use 4QPM data taken in November 2004. No point-like signal with the brightness of the companion candidate (apparent magnitudes L’=11.2 or Ks ~ 12.5) is detected at projected distances down to 6.5 AU from the star in the 2009 data.

As expected, the non-detection does not allow to rule out a background object; however, we show that it is consistent with the orbital motion of a bound companion that got closer to the star since first observed in 2003 and that is just emerging from behind the star at the present epoch. We place strong constraints on the possible orbits of the companion and discuss future observing prospects.

Comments: 8 pages, 8 figures, 1 table, accepted for publication in Astronomy and Astrophysics

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP); Instrumentation and Methods for Astrophysics (astro-ph.IM); Solar and Stellar Astrophysics (astro-ph.SR)

Cite as: arXiv:0906.5520v2 [astro-ph.EP]

Submission history

From: David Ehrenreich [view email] [via CCSD proxy]

[v1] Tue, 30 Jun 2009 13:48:26 GMT (286kb)

[v2] Wed, 1 Jul 2009 14:37:52 GMT (2046kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0906.5520

Dust Distribution in the beta Pictoris Circumstellar Disks

Authors: Mirza Ahmic, Bryce Croll (University of Toronto), Pawel Artymowicz (University of Toronto at Scarborough)

(Submitted on 3 Sep 2009)

Abstract: We present 3-D models of dust distribution around beta Pictoris that produce the best fits to the Hubble Space Telescope Advanced Camera for Surveys’ (HST/ACS) images obtained by Golimowski and co-workers. We allow for the presence of either one or two separate axisymmetric dust disks. The density models are analytical, radial two-power-laws joined smoothly at a cross-over radius with density exponentially decreasing away from the mid-plane of the disks.

Two-disk models match the data best, yielding a reduced chi^2 of ~1.2. Our two-disk model reproduces many of the asymmetries reported in the literature and suggests that it is the secondary (tilted) disk which is largely responsible for them.

Our model suggests that the secondary disk is not constrained to the inner regions of the system (extending out to at least 250 AU) and that it has a slightly larger total area of dust than the primary, as a result of slower fall-off of density with radius and height.

This surprising result raises many questions about the origin and dynamics of such a pair of disks. The disks overlap, but can coexist owing to their low optical depths and therefore long mean collision times. We find that the two disks have dust replenishment times on the order of 10^4 yr at ~100 AU, hinting at the presence of planetesimals that are responsible for the production of 2nd generation dust.

A plausible conjecture, which needs to be confirmed by physical modeling of the collisional dynamics of bodies in the disks, is that the two observed disks are derived from underlying planetesimal disks; such disks would be anchored by the gravitational influence of planets located at less than 70 AU from beta Pic that are themselves in slightly inclined orbits.

Comments: 15 pages, 13 figures, accepted by ApJ

Subjects: Solar and Stellar Astrophysics (astro-ph.SR)

Cite as: arXiv:0909.0730v1 [astro-ph.SR]

Submission history

From: Bryce Croll [view email]

[v1] Thu, 3 Sep 2009 19:09:21 GMT (1368kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0909.0730

51 Ophiuchus: A Possible Beta Pictoris Analog Measured with the Keck Interferometer Nuller

Authors: Christopher C. Stark, Marc J. Kuchner, Wesley A. Traub, John D. Monnier, Eugene Serabyn, Mark Colavita, Chris Koresko, Bertrand Mennesson, Luke D. Keller

(Submitted on 9 Sep 2009)

Abstract: We present observations of the 51 Ophiuchi circumstellar disk made with the Keck interferometer operating in nulling mode at N-band. We model these data simultaneously with VLTI-MIDI visibility data and a Spitzer IRS spectrum using a variety of optically-thin dust cloud models and an edge-on optically-thick disk model.

We find that single-component optically-thin disk models and optically-thick disk models are inadequate to reproduce the observations, but an optically-thin two-component disk model can reproduce all of the major spectral and interferometric features. Our preferred disk model consists of an inner disk of blackbody grains extending to ~4 AU and an outer disk of small silicate grains extending out to ~1200 AU.

Our model is consistent with an inner “birth” disk of continually colliding parent bodies producing an extended envelope of ejected small grains. This picture resembles the disks around Vega, AU Microscopii, and Beta Pictoris, supporting the idea that 51 Ophiuchius may be a Beta Pictoris analog.

Comments: 26 pages, 8 figures

Subjects: Solar and Stellar Astrophysics (astro-ph.SR)

Journal reference: ApJ 703 (2009) 1188-1197

Cite as: arXiv:0909.1821v1 [astro-ph.SR]

Submission history

From: Christopher Stark [view email]

[v1] Wed, 9 Sep 2009 20:44:59 GMT (189kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0909.1821