Keep your eye on a program called the Hubble Cloud Atlas. This is a collaboration between fourteen exoplanet researchers around the globe that is intent on creating images of exoplanets using the Hubble Space Telescope. But while we’ve been able to directly image a small number of planets before now, the Cloud Atlas project brings a new twist. The plan is to create time-resolved images that can tease out details about planetary atmospheres.

The test case is the planet 2M1207b, about 160 light years out in the constellation Centaurus. Infrared imaging made it possible to directly observe this planet in April of 2004, a task accomplished by researchers from the European Southern Observatory using data from the Very Large Telescope at Paranal (Chile). What we know about this planet makes it a formidable — and definitely uninhabitable — object, one with a surface temperature in the 1700 K range.

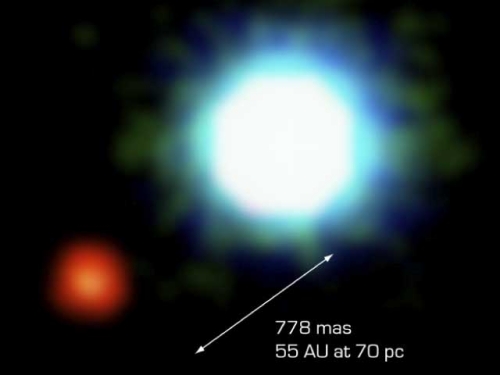

Image: The 2M1207 star system, showing the faint red object 2M1207b, a planet four times the mass of Jupiter whose atmospheric properties are now under investigation. This is an earlier image — not part of the Hubble work — taken with the high-resolution adaptive-optic NaCo camera attached to the 8-meter Very Large Telescope Yepun instrument in Chile. Credit: ESO.

At four times the mass of Jupiter, 2M1207b orbits a brown dwarf at a distance roughly comparable to Pluto’s from the Sun. Its searing heat, then, isn’t due to proximity to the brown dwarf but to gravitational contraction. This is a planet perhaps only ten million years old, and as it continues to contract, its rain likely falls in the form of liquid iron and glass. University of Arizona graduate student Yifan Zhou, lead author of the paper on this work, has been studying the distant world by taking 160 Hubble images over the course of a ten hour run.

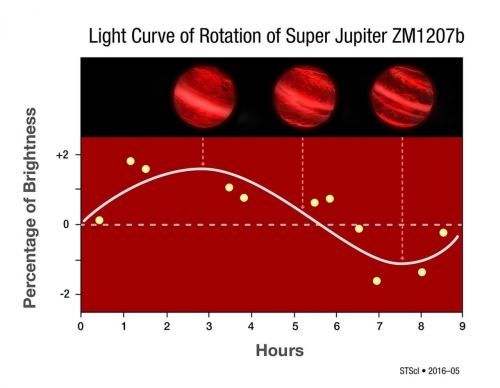

Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3, with high-resolution and high-contrast imaging capabilities, makes the work possible, but this is the first time anyone has used the space telescope to create time-resolved images of an exoplanet. This becomes a way of mapping a planet’s clouds even without being able to see them in sharp relief. Instead, the researchers measure the changes in brightness that occur over time as the planet completes its 11-hour rotation.

Image: This graph shows changes in the infrared brightness of 2M1207b as measured by the Hubble Space Telescope. Over the course of the 10-hour observation, the planet showed a change in brightness, suggesting the presence of patchy clouds that influence the amount of infrared radiation observed as the planet rotates. Credit: NASA, ESA, Y. Zhou (University of Arizona), and P. Jeffries (STScI).

Data collection for the Hubble Cloud Atlas program began in 2014. Daniel Apai (University of Arizona), who is lead investigator for the program, describes it this way on his website:

The program is using high-precision, time-resolved photometry and spectroscopy of these rotating objects to derive course maps of their cloud structures. By comparing the cloud maps between different objects we can determine how the cloud properties (covering fraction, cloud thickness, vertical structure) depend on the upper atmosphere’s temperature and the surface gravity of the objects.

And from the paper:

… we note that the observations presented here open an exciting new window on directly imaged exoplanets and planetary-mass companions. Our study demonstrates a successful application of high contrast, high-cadence, high-precision photometry with planetary mass companion. We also show that these observations can be carried out simultaneously at multiple wavelengths, allowing us to probe multiple pressure levels. With observation of a larger sample and at multiple wavelengths, we will be able to explore the detailed structures of atmospheres of directly imaged exoplanets, and identify the key parameters that determine these.

Zhou’s work with 2M1207b, which began in 2014, has bolstered the new Hubble Cloud Atlas program, and points to how we can further use Hubble as well as the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope to study planetary atmospheres and map cloud structures. Zhou was able to deduce the planet’s rotational period and probe its atmospheric properties in ways that existing Earth-based telescopes cannot. As our catalog of directly imaged planets grows, we’ll acquire new targets with which to hone these methods and eventually apply them to smaller worlds.

The paper is Zhou et al., “Discovery of Rotational Modulations in the Planetary-Mass Companion 2M1207b: Intermediate Rotation Period and Heterogeneous Clouds in a Low Gravity Atmosphere,” The Astrophysical Journal Vol. 818, No. 2 (18 February 2016). Abstract / preprint available.

I’m no expert, but wouldn’t similar techniques that measure brightness reveal surface features like seasonal changes in polar ice coverage on rocky planets?

The problem is that rocky planets are much smaller than gas giants.

http://www.meteoritesusa.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/jupiter_earth_impact.jpg

Rocky planets are indeed smaller that gas giants. I should have added an “in the near future” somewhere in the original question. I would be surprised if the designers of Hubble anticipated the telescope could be used to glean information about cloud cover on an exoplanet. I am confident that the next generation of telescopes will deliver similar surprises.

We are a long way from seeing surface features on any planet directly. All these changes are cleverly interpreted from either changes in the spectrum of starlight passing through the atmosphere of a transiting planet ( including Doppler shift ) or else the spectrum of a “hot” planet radiating enough heat to have its own emission spectrum which can now be measured spectscopically . The WCF3 camera on 2.4m Hubble was never developed with this in mind so it’s a truly tremendous achievement . Light years can mislead as to the multi trillions of miles away these exoplanets are. That said it does make you wonder just what the 6.5m dedicated spectroscopic JWST can achieve on the 250 planets or so it is planned to observe in this way. Better still would be a dedicated telescope , transit spectroscopy telescopes aren’t particularly complicated in design and as spectrum opt is based on photon numbers , smaller apertures can make up in time what they lack in size . A 1.5m scope could characterise a habitable zone planet around a later M dward star like Proxima at the least.

As I’ve said before , JWST will give respectable spectroscopic resolution on Super Earths and even Earth sized planets ,if near enough, in the habitable zone around nearby M dwarfs . Spectroscopy has come on so far that it can almost tell as much as a direct image , certainly one of only a few pixels.

In addition to heat from ongoing gravitational contraction ( most large mass “Jupiters” aren’t much bigger than our Jupiter because of this ) this planet is only a few tens of millions of years old so still possess a lot of its heat of formation which it will lose via radiation over another few million years.

Telescopic resolution is calculated by 1.22 wavelength /D with D being the aperture of the telescope in m . Even though visible light has a wavelength of just nano metres this is a long , long way short of the resolution required for direct imaging any exoplanet .To give some idea, it has been calculated that to directly resolve the surface features on even the nearest Earth sized planet would require an aperture of a 150km , 150000m or more (or the equivalent multi telescope interferometer) . Tough and expensive to say the least ( when you think that even the biggest ELT will have a diameter of just 30m) and even this would only give about ten pixels or so . Jupiter would require less but still a serious telescope. I think if this is ever achieved it will be via interferometry . Optical interferometry has still got a long way to go to achieve the thousands of kilometre baselines of radio telescopes , but I’m sure it will get there one day. Labeyrie calculated two hundred 3m scopes linked in formation with a maximum baseline of 150km will do it.

Could some of the patchiness possibly be due to moons, either shadowing or transiting? I was wondering if there is a consistent pattern, or if it just changes. Seeing clouds is great, but finding moons would be exciting indeed!

That’s exactly what JWST hopes to do.

This is not a planet but another brown dwarf ,just a smaller one and 2M1207 is a binary system.

In my opinion most of these super jupiter are not planets but failed stars ,ie brown dwarfs.

Brown dwarfs seem to form from their own accretion disks rather than those of a star. They also ( minimum mass approximately 13 Jupiters) carry out limited fusion of deuterium and to a lesser degree lithium , for the few million years the low levels of these materials allow . Critically they DONT fuse hydrogen because their core doesn’t get hot enough ( approx 1 million Kelvin to fuse deuterium , 15 million kelvin for Hydrogen )

How hot Jupiter exoworlds defy logic – assuming human logic applies to the rest of the Universe:

http://www.space.com/32011-extremely-hot-and-fast-planets-seem-to-defy-logic.html

New imaging technique can find Earth-like planets near their stars

http://www.redorbit.com/news/space/1113412756/new-imaging-technique-spots-earth-like-planets-near-their-stars-022316/

A potentially revolutionary development . 7e7 contrast without any occulting device is a very good start . The key to this now is just how close to the star it can achieve this sort of performance .

Spoken to lead at the Florida Institute of .technology . Like CMOS sensors , the CID is a reimagined technology having been used in the past but temporarily surpassed by the CCD. It has enormous potential having already had a lot of redevelopment .

The team are working on a more advanced version with up to 1 billion contrast ratio-as good as that proposed for WFIRST, but without a star shade or coronagraph . Once mature ( a preliminary smaller mission will achieve Nasa technological readiness ) , the aim is to put one in a big , 12 U Cubesat, as part of a small telescope or better still a fleet of such telescopes . A weakness is that a CID does not modify the Point Spread Function of a point source of light like an exoplanet and is totally reliant on image ” post processing ” like Angular Differential Imaging ,ADI, Spectral Differential Imaging or “Roll Differential technology ” which as far as I can see is the space equivalent of ADI with rotation of the telescope by up to 30 degrees to remove speckles. The net result , less than 100 mas IWA ( an AU at ten parsecs ) . That matches or betters current coronagraph or star shade concepts.

A genuine “third way” and as it all fits into a cubesat , seriously good value if it works . With Sara Seagers 6U ASTERIA transit spectroscopy cubesat due to launch in the summer after several years of intensive development/maturation I think the age of the Cubesat is almost upon us with exoplanetology a major beneficiary . Things are going to start getting very interesting with dedicated exoplanet telescope fleets atlast ( making up in time of observation what they lack in size ) .

Combine that with the extensive expertise already gleaned from WFIRST and the direct imaging suites on the Gemini ,VLT and Suburu telescopes plus transit spectroscopy through the Hubble WFC3 and Spitzer and things could move on very quickly !

Could we really image exo-planets, even in theory, given the limited amount of light that is available?

Let’s assume an Earth sized planet in a habitable zone of the Alpha Centauri system. We can calculate that from each square meter of illuminated planet surface, we receive roughly 5 * 10^-13 photons per second in each square meter of aperture. At full phase, the planet presents an area of 10^14 square meters. So, if the planet is resolved to a single pixel, we get around 2 photons per second for each square meter of aperture.

If we wanted to resolve the planet to 100 pixels (10 x 10), we would need a real aperture of at least 100 m^2. The interferometry baseline dictated by the diffraction limit would have to be much higher, more like the 150km Ashley Baldwin has mentioned, above. So, provided we have a way to phase-compare images over distances of hundreds of kilometers, the light gathering requirement for imaging exoplanets are not too onerous. The 10 x 10 pixel resolution image (I think this is roughly what we had of Pluto before New Horizon) could be achieved using 100 1 m telescopes flying in formation a few hundred kilometers from each other, linked together interferometrically in some way.

This sounds easy, but it is not. It would be great if we could follow the VLBA and simply record the light with phase information, but I do not think this can currently be done. Another, somewhat equivalent method would be to count individual photons and measure their arrival times to extremely high accuracy. Yet another possibility is intensity correlation interferometry, which we have talked about in these pages before. The difficulties appear surmountable, and my guess is that we will work all this out and have the capability within a few decades.

We could use the moons diameter ~3400 km as the baseline with scopes dotted all over the surface, they can be used day and night. During the day a tube ‘flower petal style’ could be used to shield the telescope and still view. There are plenty of materials on the moon to make the telescopes and silvering the scope would be much easier than on earth. I just love the simplicity of time stamping the photon arrival times and then putting them together again as one coherent image.

Formations in deep space are better and easier than structures on the moon, in my opinion. For one, they are more easily reconfigured and expanded. Besides, it will be a long time until we can build telescopes from off-Earth resources.

With the moon there is plenty of resources to build many more and service them more easily than in deep space.

http://www.space.com/5628-nasa-envisions-huge-lunar-telescope.html