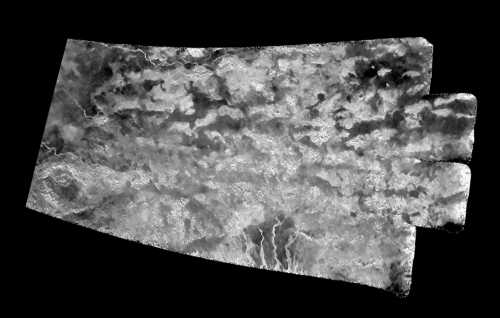

Have a look at an image Cassini acquired on July 25 of this year during its T-121 flyby of Titan. Here we’re dealing with a synthetic-aperture radar image, but one that has been cleaned up with a ‘denoising’ algorithm that produces clearer views. Because of its proximity to the Xanadu region, the mountainous terrain shown here has been named the ‘Xanadu annex’ by Cassini controllers. Both features block the formation of sand dunes, which are elsewhere ubiquitous around Titan’s equator. As on Earth, Titan’s dunes flow around the obstacles they meet.

These are the first Cassini images of the Xanadu annex, which is now revealed to be made up of the same mountainous terrain seen in Xanadu itself. Referring to the first detection of Xanadu, which occurred in 1994 through Hubble Space Telescope observations, JPL’s Mike Janssen, a member of the Cassini radar team, calls the annex ‘an interesting puzzle,’ adding:

“This ‘annex’ looks quite similar to Xanadu using our radar, but there seems to be something different about the surface there that masks this similarity when observing at other wavelengths, as with Hubble.”

Image: The area nicknamed the “Xanadu annex” by members of the Cassini radar team, earlier in the mission. This area had not been imaged by Cassini’s radar until now, but measurements of its brightness temperature from Cassini’s microwave radiometer were quite similar to that of the large region on Titan named Xanadu. Cassini’s radiometer is essentially a very sensitive thermometer, and brightness temperature is a measure of the intensity of microwave radiation received from a feature by the instrument. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/Universite Paris-Diderot.

While mountainous terrain is found elsewhere on Titan, the Xanadu region is large and somewhat reminiscent of a famous area in the north-central US, according to Rosaly Lopes (JPL), a member of the Cassini radar team. Says Lopes:

“These mountainous areas appear to be the oldest terrains on Titan, probably remnants of the icy crust before it was covered by organic sediments from the atmosphere. Hiking in these rugged landscapes would likely be similar to hiking in the Badlands of South Dakota.”

Cassini closed to within a bit less than a thousand kilometers of Titan on the T-121 pass, its radar looking through the moon’s global haze to produce details of the surface. JPL has produced a video that shows long, linear dunes that scientists believe are made up of grains derived from hydrocarbons settling out of Titan’s atmosphere.

We have four Cassini flybys of Titan left before mission’s end, and this one marks the last time the spacecraft’s radar will image the far southern latitudes. The remaining flybys are to focus on the far north, an area famous for its lakes and seas. Maybe it’s just the gradual approach of autumn here in North America, but all of these late flybys have a kind of elegiac quality for me. After all, it will be next spring that the spacecraft begins the series of orbits that take it between Saturn and its rings, to be followed by entry into Saturn’s atmosphere on September 15, 2017.

Cassini’s fiery end is a move designed to prevent any biological contamination of Titan, Enceladus and any other conceivable habitat, but it’s going to be painful to watch given the rich data and imagery the craft has given us since orbital insertion at Saturn in July of 2004.

If you put OPAG ( Outer Planets Assessment Group) and Nasa into Google you will find a link to the OPAG meeting on the 11 August that includes a very nice review of the remaining Cassini mission by Linda Spilker. Still a massive amount of science to be done , including Titan and its lakes in detail and a mission within a mission that is essentially JUNO for Saturn . Not like me to be like me to be all anthropomorphic but “glorious finale ” or not , a sad day for me September 15 next year. I can’t help feeling it deserves a better memorial after 13 years of triumphant scientific achievement with over 3600 peer reviewed journals . Tear in my eye.

The OPAG meeting includes numerous other interesting presentations well worth a look including the “Ice Giants” , Juno and Europa . Hopefully plenty to look forward to if we all live long enough !

The (Anglo Polish) Huygens probe is still resting on Titan

No sign of frozen Sirens (they must look like chilly mermaids) swimming in the Lakes of methane yet.

Doug

Maybe some day the Methane of Titan will turn out to be the beckoning Sirens.

When Huygens is one day found, the discoverers will also find a CD-ROM attached to the historic lander. The disc contains four pop songs, composed by French musicians Julien Civange and Louis Haéri.

Four articles on the subject:

http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Science/Cassini-Huygens/Rock_n_roll_heading_for_Titan

http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Science/Cassini-Huygens/Music2Titan_sounds_of_a_spaceprobe

http://www.abc.net.au/science/news/stories/s1248542.htm

http://www.stufftoblowyourmind.com/blogs/space-music-music-on-titan-sistema-drokk-and-alan-howarth.htm

On a related note of the merging of art (music) and space science with Saturn’s largest moon, here is something called Capsule Titan:

http://www.eowave.com/modules/capsule-titan/

To quote from the Web page:

“The Capsule Titan is an immersive experimentation, delving into the mysteries of space through the medium of sound design and music. In a way, the Capsule Titan is a simulation station able to reproduce the journey of the sound waves crossing Titan’s dense, orange atmosphere and offer the possibility to modulate parameters like the thickness of the haze, the ionisation of the magnetosphere, and Titan’s magnetic glow (or low frequency zones). To amplify these sounds, we’ve chosen a discrete amplification.”

As the original site, Music2Titan, appears to have gone away, here are the songs on the Huygens CD-ROM courtesy of YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=music2titan

Just to make a small correction: Huygens isn’t an Anglo-Polish probe, it’s an European probe to which some countries participating in the European Space Agency (ESA) contributed. Amongst them: Italy, Austria, Germany, Spain, France, the United Kingdom, Norway, and Finland. Poland didn’t contributed directly to build the probe but it is also part of ESA.

Huygens was originally the name of a Dutch scientist.

Here is a nice introduction to the amazing Christiaan Huygens, from the Cosmos series by Carl Sagan in Episode 6, “Travelers’ Tales”:

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x1h5o31_carl-sagan-s-cosmos-e06-travellers-tales_tv

If you want to meet a man ahead of his time, yet also very much part of the best of his own era, then you must read Huygens’ magnum opus on extraterrestrial life, Cosmotheoros, which you can do online here:

https://www.staff.science.uu.nl/~gent0113/huygens/huygens_ct_en.htm

Cosmotheoros was the first science text to appear in Russia in the Russian language. Peter the Great was a big fan of the book:

http://www.ritmanlibrary.com/2013/06/peter-the-great-and-christiaan-huygens/

If anyone deserved to have their name on a space probe, it was Huygens. Even if Huygens had not discovered Titan in 1656, he would still deserve to have his name on that lander. He was one of the earliest scientists to determine that Saturn’s rings were neither giant moons (as Galileo had thought) nor touching the planet itself.

Hydrocarbon sand dunes. Interesting! Passive microwave radiometer.

Thank you, Paul. I am absolutely fascinated by Titan!

How can we be sure that Cassini’s re-entry will be fiery enough to sterilize it?

I’ll check on this — don’t really know what’s expected on Cassini atmosphere entry.

From our friends at “Nausea”:

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/faq/

“Based upon exposure experiments on the Space Station, it is known that some microbes and microbial spores from Earth are able to survive many years in the space environment– even with no air or water, and minimal protection from radiation. Therefore, NASA has chosen to dispose of the spacecraft in Saturn’s atmosphere in order to avoid the possibility that viable microbes from Cassini could potentially contaminate Saturn’s moons at some time in the future.”

For some reason I thought they were planning to de-orbit into Titan itself. That would muddy the waters, no doubt about it.

They would never have done that. They would never go near Enceladus either.

The Planetary Society detailed the final three years of Cassini in 2014:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2014/cassinis-awesomeness-fully.html

I was trying to find how fast Cassini will be going when it plunges into the atmosphere of Saturn, but if it is moving at anything like the Galileo probe did when it hit the atmosphere of Jupiter in 2003 (approximately 173,736 kilometers per hour, or 107,955 miles per hour), I doubt any lingering terrestrial microbes will survive the heat of entry.

Assuming Cassini does not crash into a ring particle beforehand.

Titan’s lakes during their summer:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2016/09121142-cassinis-camera-views-titan-lakes.html

One year remains in the Cassini mission

Posted by Emily Lakdawalla

2016/09/15 14:27 UTC

Cassini has been orbiting Saturn for as long as I’ve been a science writer. From the time of its orbit insertion in June 2004, Cassini was the first regular beat I was asked to cover as a writer at The Planetary Society. So it’s especially hard for me to confront the fact that this long, wonderful mission is just about over. A year from today, it’s going to plunge into Saturn.

The mission must end because it is nearly out of fuel. Originally planned to last 4 years in orbit, the mission was extended twice to cover Saturn over a total of half of its year around the Sun. Cassini arrived at the height of southern summer, and has watched as the Sun set on the south pole and rose on the north pole. The mission will see Saturn go through northern summer solstice before it ends.

The final year is going to be an exciting one. On November 29, a flyby of Titan will drop Cassini’s closest approach to Saturn to a point just 10,000 kilometers beyond the F ring. Cassini will be able to study the weird phenomena of Saturn’s rings and ringmoons closer than ever before, and will travel to never-before-sampled regions of Saturn’s magnetic field. Then, on April 22, 2017, a final targeted flyby of Titan will shift Cassini’s periapsis to a point between the innermost D ring and Saturn. On each close approach to Saturn, it’ll fly within 3800 kilometers of the cloud tops. Cassini will see the planet, rings, and energetic particle environment from a new perspective, and have the first ever opportunity to measure the masses of the ring system and Saturn separately. A final nudge by distant Titan on September 15, 2017, will send Cassini to its death.

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2016/09150727-one-year-remains-in-cassini.html

To quote:

This final year of Cassini’s mission will actually look an awful lot like the Juno mission — a spacecraft in a studying the inner workings of a giant planet from a polar, elliptical orbit that passes very close to the planet at periapsis. Except that Cassini carries a much larger (albeit older-tech and more-worn) instrument package. The fact that we’ll have two spacecraft operating similar missions at different planets at the same time in the same solar environment will multiply our ability to understand how stars influence the physics of giant planets, and how giant planets work more generally. Basically, this final year of the Cassini mission will be like a whole New Frontiers mission tacked on to the end of a flagship mission. It’s going to be awesome.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1610.04515

The Pale Orange Dot: The Spectrum and Habitability of Hazy Archean Earth

Giada Arney, Shawn D. Domagal-Goldman, Victoria S. Meadows, Eric T. Wolf, Edward Schwieterman, Benjamin Charnay, Mark Claire, Eric Hébrard, Melissa G. Trainer

(Submitted on 14 Oct 2016)

Recognizing whether a planet can support life is a primary goal of future exoplanet spectral characterization missions, but past research on habitability assessment has largely ignored the vastly different conditions that have existed in our planet’s long habitable history.

This study presents simulations of a habitable yet dramatically different phase of Earth’s history, when the atmosphere contained a Titan-like organic-rich haze. Prior work has claimed a haze-rich Archean Earth (3.8-2.5 billion years ago) would be frozen due to the haze’s cooling effects. However, no previous studies have self-consistently taken into account climate, photochemistry, and fractal hazes.

Here, we demonstrate using coupled climate-photochemical-microphysical simulations that hazes can cool the planet’s surface by about 20 K, but habitable conditions with liquid surface water could be maintained with a relatively thick haze layer (tau ~ 5 at 200 nm) even with the fainter young sun.

We find that optically thicker hazes are self-limiting due to their self-shielding properties, preventing catastrophic cooling of the planet. Hazes may even enhance planetary habitability through UV shielding, reducing surface UV flux by about 97% compared to a haze-free planet, and potentially allowing survival of land-based organisms 2.6.2.7 billion years ago. The broad UV absorption signature produced by this haze may be visible across interstellar distances, allowing characterization of similar hazy exoplanets.

The haze in Archean Earth’s atmosphere was strongly dependent on biologically-produced methane, and we propose hydrocarbon haze may be a novel type of spectral biosignature on planets with substantial levels of CO2.

Hazy Archean Earth is the most alien world for which we have geochemical constraints on environmental conditions, providing a useful analog for similar habitable, anoxic exoplanets.

Comments: 111 pages, 15 figures, 4 tables, accepted for publication in Astrobiology

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:1610.04515 [astro-ph.EP]

(or arXiv:1610.04515v1 [astro-ph.EP] for this version)

Submission history

From: Giada Arney [view email]

[v1] Fri, 14 Oct 2016 16:08:28 GMT (8117kb)

https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1610/1610.04515.pdf

March 15, 2017

Experiments Show Titan Lakes May Fizz with Nitrogen

A recent NASA-funded study has shown how the hydrocarbon lakes and seas of Saturn’s moon Titan might occasionally erupt with dramatic patches of bubbles.

For the study, researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, simulated the frigid surface conditions on Titan, finding that significant amounts of nitrogen can be dissolved in the extremely cold liquid methane that rains from the skies and collects in rivers, lakes and seas. They demonstrated that slight changes in temperature, air pressure or composition can cause the nitrogen to rapidly separate out of solution, like the fizz that results when opening a bottle of carbonated soda.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has found that the composition of Titan’s lakes and seas varies from place to place, with some reservoirs being richer in ethane than methane. “Our experiments showed that when methane-rich liquids mix with ethane-rich ones — for example from a heavy rain, or when runoff from a methane river mixes into an ethane-rich lake — the nitrogen is less able to stay in solution,” said Michael Malaska of JPL, who led the study.

The result is bubbles. Lots of bubbles.

Full article here:

https://www.nasa.gov/feature/jpl/experiments-show-titan-lakes-may-fizz-with-nitrogen