Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

OSIRIS-REx: Orbital Operations at Bennu

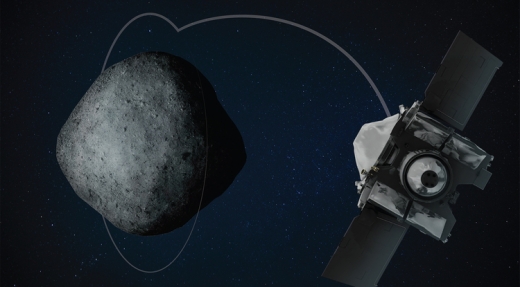

Sometimes one mission crowds out another in the news cycle, which is what has happened recently with OSIRIS-REx. The study of asteroid Bennu, significant in so many ways, continues with the welcome news that OSIRIS-REx is now in orbit, making Bennu the smallest object ever to be orbited by a spacecraft. That milestone was achieved at 1943 UTC on December 31, which in addition to the upcoming New Year’s celebration was also deep into the countdown for New Horizons’ epic flyby of MU69, the Kuiper Belt object widely known as Ultima Thule.

Image credit: Heather Roper/University of Arizona.

I suppose the classic case of mission eclipse was the Voyager flyby of Uranus, which occurred on January 24, 1986. I was flying commercial students in a weekend course four days later in Frederick, MD and anxious to hear everything I could about the flyby, its images and their analysis, but mid-morning between flights I learned about the Challenger explosion, and the news for days, weeks, was filled with little else. Now, of course, we can study the striking images of Uranus’ rings and the tortured moon Miranda, putting them in the great context of Voyager exploration, but for a time the story was mute.

OSIRIS-REx has a long period of mapping and sampling ahead of it, with the sample site selection gearing up, and we’ll have plenty to say about it in coming weeks. Ponder that the spacecraft orbits Bennu from a distance just 1.75 kilometers from its center, a tighter value even than Rosetta’s, when it orbited 7 kilometers from the center of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

From OSIRIS-REx flight dynamics system manager Mike Moreau (NASA GSFC):

“Our orbit design is highly dependent on Bennu’s physical properties, such as its mass and gravity field, which we didn’t know before we arrived. Up until now, we had to account for a wide variety of possible scenarios in our computer simulations to make sure we could safely navigate the spacecraft so close to Bennu. As the team learned more about the asteroid, we incorporated new information to hone in on the final orbit design.”

Using 3-D models of Bennu’s terrain created from OSIRIS-REx’s recent global imaging and mapping campaign, the mission team intensifies its navigation survey, and will analyze changes in the spacecraft’s orbit to study the minute gravitational pull of the object, which should tighten up existing models of not just the gravity field, but Bennu’s thermal properties and spin rate. By the summer of 2020, controllers will be ready for the spacecraft to touch the surface for sampling operations, with the sample scheduled for return to earth in September of 2023.

New Horizons Healthy and Full of Data

We’ve just learned that New Horizons is intact and functional, with a ‘phone home’ message at about 1530 UTC that checked off subsystem by subsystem — all nominal — amidst snatches of applause at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. The solid state recorders (SSR) are full, with pointers indicating that flyby information is there for the sending, even as the spacecraft continues with outbound science. New Horizons will pass behind the Sun in early January, giving us a break in communications for a few days this weekend. Over the next 20 months we will get the entire package from Ultima Thule. Patience will be in order.

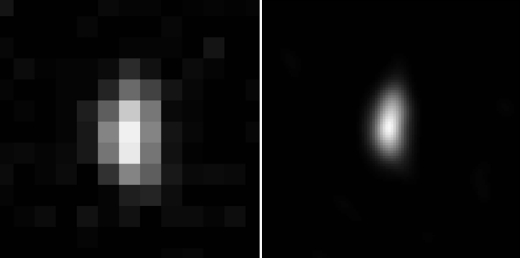

Here’s the approach image that was released yesterday.

Image: Just over 24 hours before its closest approach to Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule, the New Horizons spacecraft has sent back the first images that begin to reveal Ultima’s shape. The original images have a pixel size of 10 kilometers (6 miles), not much smaller than Ultima’s estimated size of 30 kilometers (20 miles), so Ultima is only about 3 pixels across (left panel). However, image-sharpening techniques combining multiple images show that it is elongated, perhaps twice as long as it is wide (right panel). This shape roughly matches the outline of Ultima’s shadow that was seen in observations of the object passing in front of a star made from Argentina in 2017 and Senegal in 2018. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

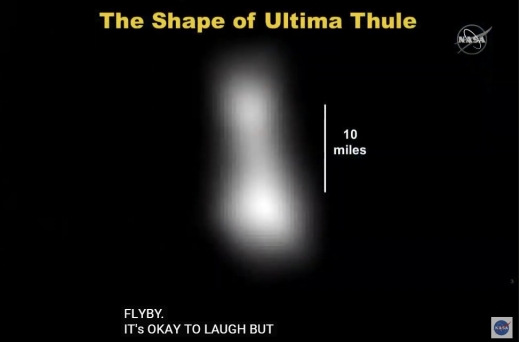

And here’s the best approach image, released a few minutes ago at the press briefing.

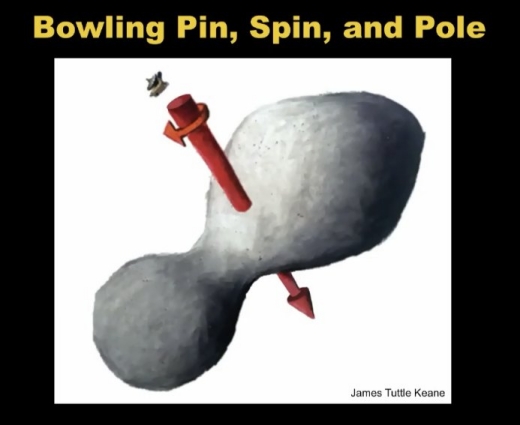

The bi-lobate structure is obvious, but is it a single object or two in tight orbit of each other? We should have the answer to that question in an image that will be released tomorrow. Project scientist Hal Weaver displayed the slide below showing the shape and spin of Ultima. The lack of lightcurve is explained by New Horizons approaching along the line of polar rotation.

Some background thoughts:

Ultima Thule has pushed New Horizons to its limits. Mission principal investigator Alan Stern put it best at yesterday’s mid-afternoon news conference when he noted “We are straining at the capabilities of this spacecraft. There are no second chances for New Horizons.”

If the primary mission had been the long-studied flyby of Pluto/Charon, whose orbit had the benefit of decades of analysis, Ultima Thule presented controllers with an object not known until 2014, when it was discovered as part of the deliberate hunt for a Kuiper Belt object within range. Thus much about the orbit was unknown, making for what Stern described as a ‘tough intercept.’ Factor in the increased distance from the Sun far beyond Pluto and its effects on lighting conditions, as well as a power generator now producing less wattage because of its age.

Fortunately, LORRI, the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager, had spotted Ultima as far back as August 16 and the spacecraft had been imaging the object ever since, using long exposure times and co-adding procedures in which multiple optical navigation images are layered over each other, until in the last month of the approach the motion of the target could be seen, as mission project manager Helene Winters showed graphically at the same news event. Hazards like moons and rings were ruled out and the optimal trajectory, with approach to within 3500 kilometers, was available. If all went well, the early imagery will give way to fine detail.

1.6 billion kilometers beyond Pluto, New Horizons needed to hit a 40 square mile box with a timing window of 80 seconds, an epic feat of navigation that will surely wind up discussed in the next edition of David Grinspoon and Alan Stern’s book Chasing New Horizons (Picador, 2018), unless the duo decide to spin Kuiper object exploration into a book of its own. But I think not. New Horizons’ story should be seen whole, a continuing story pushed to its limits and, like the Voyagers that preceded it to system’s edge, still returning priceless data.

Ultima Thule Flyby Approaches

Despite the various governmental breakdowns attendant to the event, the New Horizons flyby of Ultima Thule is happening as scheduled, the laws of physics having their own inevitability. Fortunately, NASA TV and numerous social media outlets are operational despite the partial shutdown, and you’ll want to keep an eye on the schedule of televised events as well as the New Horizons website and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory YouTube channel.

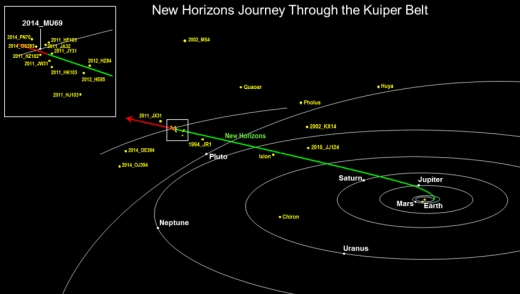

Image: New Horizons’ path through the solar system. The green segment shows where New Horizons has traveled since launch; the red indicates the spacecraft’s future path. The yellow names denote the Kuiper Belt objects New Horizons has observed or will observe from a long distance. (NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI).

We’re close enough now, with flyby scheduled for 0533 UTC on January 1, that the mission’s navigation team has been tightening up its estimates of Ultima Thule’s position relative to the spacecraft, key information when it comes to the timing and orientation of New Horizons’ observations. Raw images from the encounter will be available here. Bear in mind how tiny this object is — in the range of 20 to 30 kilometers across — so that we have yet to learn much about its shape and composition, though we’ve already found that it has no detectable light curve.

On the latter point, mission principal investigator Alan Stern (SwRI):

“It’s really a puzzle. I call this Ultima’s first puzzle – why does it have such a tiny light curve that we can’t even detect it? I expect the detailed flyby images coming soon to give us many more mysteries, but I did not expect this, and so soon.”

Thus the mission proceeds in this last 24 hours before flyby with grayscale, color, near-infrared and ultraviolet observations, along with longer-exposure imaging to look for objects like rings or moonlets around Ultima. Closest approach is to be 3,500 kilometers at a speed of 14.43 kilometers per second. JHU/APL is reporting that the pixel sizes of the best expected color and grayscale images and infrared spectra will be 330 meters, 140 meters and 1.8 kilometers, respectively, with possible images at 33-meter grayscale resolution depending on the pointing accuracy of LORRI, the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager.

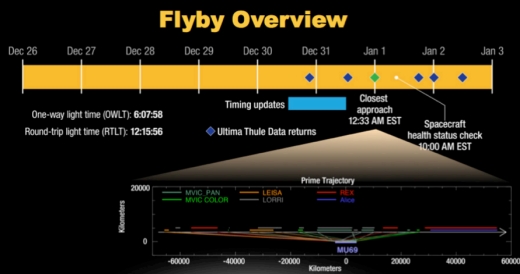

Image: New Horizons’ cameras, imaging spectrometers and radio science experiment are the busiest members of the payload during close approach operations. New Horizons will send high-priority images and data back to Earth in the days surrounding closest approach; placed among the data returns is a status check – a “phone home signal” from the spacecraft, indicating its condition. That signal will need just over 6 hours, traveling at light speed, to reach Earth. (NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI).

Post flyby, New Horizons will turn its ultraviolet instrument back toward the Sun to scan for UV absorption by any gases the object may be releasing, while simultaneously renewing the search for rings. Scant hours after the flyby, New Horizons will report back on the success of the encounter, after which the downlinking of approximately 7 gigabytes of data can begin. The entire downlink process, as at Pluto/Charon, is lengthy, requiring about 20 months to complete.

Let’s keep in mind that, assuming all goes well at Ultima Thule, we still have a working mission in the Kuiper Belt, one with the potential for another KBO flyby, and if nothing else, continuing study of the region through April of 2021, when the currently funded extended mission ends (a second Kuiper Belt extended mission is to be proposed to NASA in 2020). The Ultima Thule data return period will be marked by continuing observation of more distant KBOs even as New Horizons uses its plasma and dust sensors to study charged-particle radiation and dust in the Kuiper Belt while mapping interplanetary hydrogen gas produced by the solar wind.

So let’s get this done, and here’s hoping for a successful flyby and continued exploration ahead! It will be mid-afternoon UTC on January 1 (mid-morning Eastern US time) when we get the first update on the spacecraft’s condition, with science data beginning to arrive at 2015 UTC, and a first 100 pixel-across image (and more science data coming in) on January 2 at 0155 UTC. The best imagery is going to take time to be released, perhaps becoming available by the end of February. We’ll be talking about Ultima Thule a good deal between now and then.

Today is the day we explore worlds farther than ever in history!! EVER. #NASA #Space #Science #UltimaFlyby #ULtimaThule pic.twitter.com/3Stdh2JrMM

— Alan Stern (@AlanStern) December 31, 2018

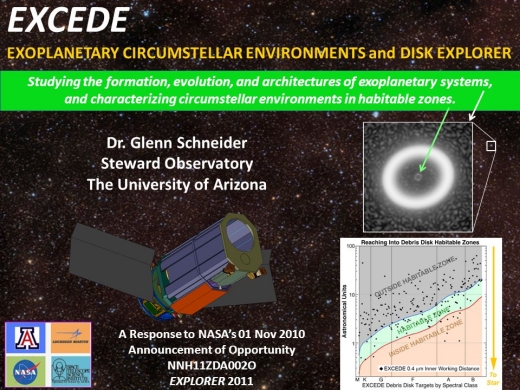

Exoplanet Imaging from Space: EXCEDE & Expectations

We are entering the greatest era of discovery in human history, an age of exploration that the thousands of Kepler planets, both confirmed and candidate, only hint at. Today Ashley Baldwin looks at what lies ahead, in the form of several space-based observatories, including designs that can find and image Earth-class worlds in the habitable zones of their stars. A consultant psychiatrist at the 5 Boroughs Partnership NHS Trust (Warrington, UK), Dr. Baldwin is likewise an amateur astronomer of the first rank whose insights are shared with and appreciated by the professionals designing and building such instruments. As we push into atmospheric analysis of planets in nearby interstellar space, we’ll use tools of exquisite precision shaped around the principles described here.

by Ashley Baldwin

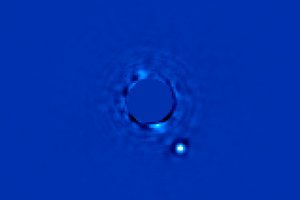

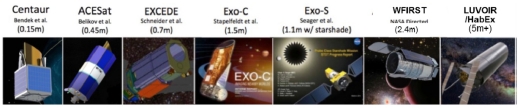

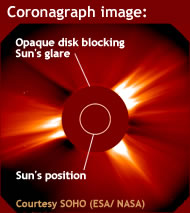

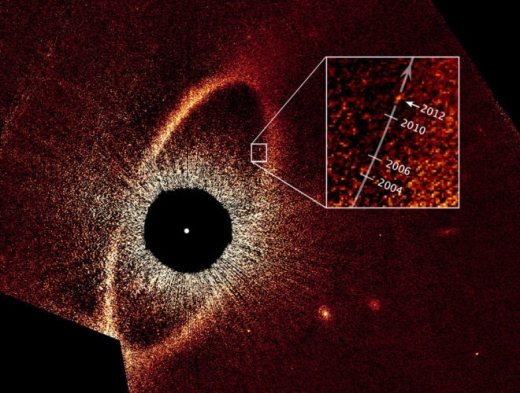

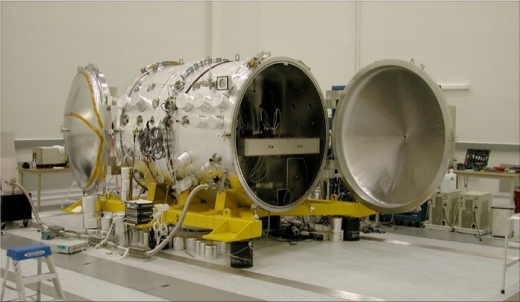

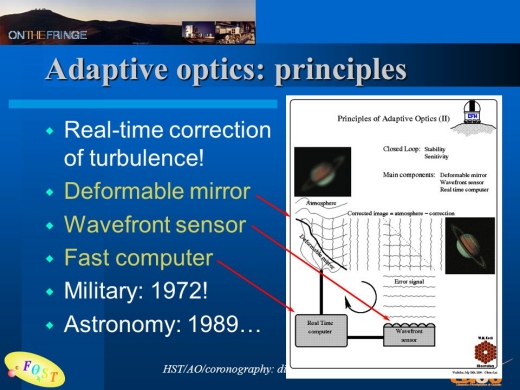

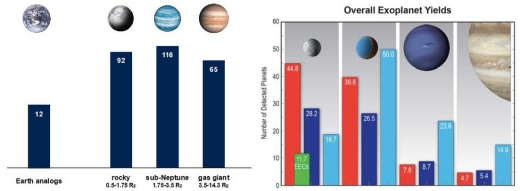

This review is going to look at the current state of play with respect to direct exoplanet imaging. To date this has only been done from ground-based telescopes, limited by atmospheric turbulence to wide orbit, luminous young gas giants. However, the imaging technology that has been developed on the ground can be adapted and massively improved for space-based imaging. The technology to do this has matured immeasurably over even the last 2-3 years and we stand on the edge of the next step in exoplanet science. Not least because of a disparate collection of “coronagraphs”, originally a simple physical block placed in the optical pathway of telescopes designed to image the corona of the Sun by French astronomer Bernard Lyot, who lends his name to one type of coronagraph.

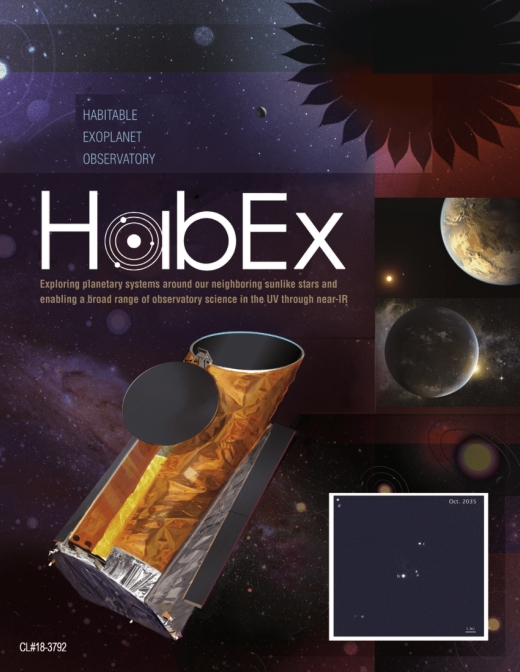

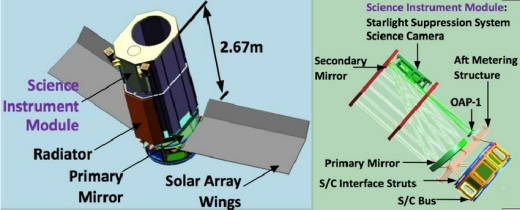

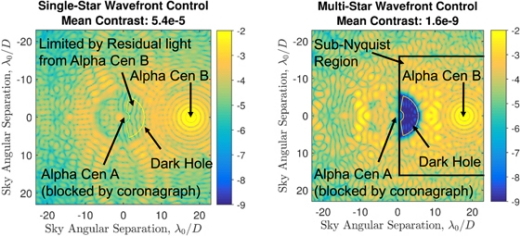

This is an instrument that in combination with ground-based pioneering work on telescope “adaptive optics” systems and advanced infrared sensors in the late 1980s and early ’90s progressed in the last ten years or so to the design of space-based instruments – later generations of which have now progressed to the point of driving telescopes like 2.4m WFIRST, 0.7m EXCEDE and 4m HabEX. Different coronagraphs work in different ways, but the basic principle is the same. On-axis starlight is blocked out as much as possible, creating a “dark hole” in the telescope field of view where much dimmer off-axis exoplanets can then be imaged.

Detailed exoplanetary characterisation including formation and atmospheric characteristics is now within tantalising reach. Numerous flagship telescopes are at various stages of development awaiting only the eventual launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and its cost overrun, before proceeding. Meantime I’ve taken the opportunity this provides to review where things are by looking at the science through the eyes of an elegant telescope concept called EXCEDE (Exoplanetary Circumstellar Environment & Disk Explorer), proposed for NASA’s Explorer program to observe circumstellar protoplanetary and debris discs and study planet formation around nearby stars of spectral classes M to B.

Image: French astronomer Bernard Lyot.

Although only a concept and not yet selected for development, I believe EXCEDE – or something like it – may yet fly in some iteration or other, bridging the gap between lab maturity and proof of concept in space and in so doing hastening the move to the bigger telescopes to come. Two of which, WFIRST (Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope) and HabEX (Habitable Exoplanet Imaging Mission) also get coverage here.

Why was telescope segmented deployability so aggressively pursued for the JWST?

“Monolithic”, one-piece mirror telescopes are heavy and bulky – which gives them their convenient rigid stability, of course.

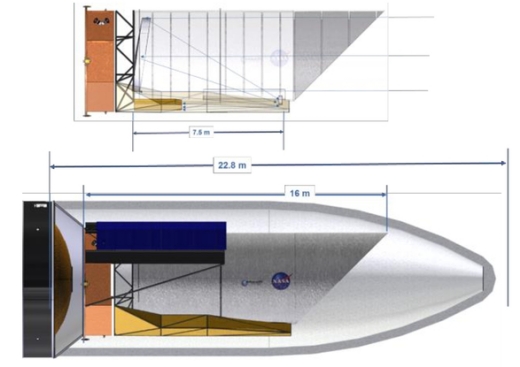

However, even a 4m monolithic mirror-based telescope would take up the full 8.4m fairing of the proposed SLS block 1b and with a starshade added would only just fit in lengthways if it had a partially deployable “scarfed” baffle. The telescope would mass around 20 tonnes built from conventional materials. Though if built with proven lightweight silicon carbide, already proven with the success of the ESA’s 3.5 m Herschel telescope, it would come in at about a quarter of this mass.

Big mirrors made out of much heavier glass ceramics like Zerodur have yet to be used in space beyond the 2.4m Hubble and would need construction of 4m-sized test “blanks” prior to incorporation in a space telescope. Bear in mind too that Herschel also had to carry four years worth of liquid coolant in addition to propellant. With minimal modification, such a similarly proportioned telescope might fit within the fairing of a modified New Glenn launcher too. If NASA shakes off its reticence about using silicon carbide in space telescope construction – something that may yet be driven – like JWST before it – by launcher availability. This given the uncertain future of the SLS and especially its later iterations.

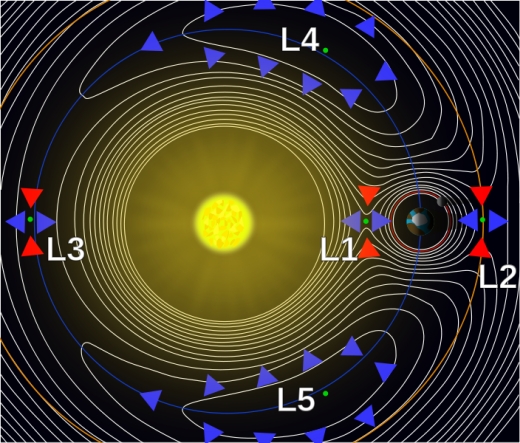

Meantime, at JWST conception there just wasn’t any suitable heavy lift/big fairing rocket available (or indeed now!) to get a single 6.5m mirror telescope into space. Especially not to the prime observation point at the Sun/Earth L2 Lagrange point 900 K miles away in deep space. And that was the aperture deemed necessary to be a worthy successor to Hubble.

An answer was found in a Keck-style segmented mirror which could be folded up for launch and then deployed after launch. Cosmic origami if you will (it may be urban myth but rumour has it origami experts were actually consulted).

The mistake was in thinking that transferring the well established principle of deployable space radio antennae to visible/IR telescopes would be (much) easier than it would turn out. The initially low cost “evolved”, but as it did so did the telescope and its descendants. From infrared cosmology telescope to “Hubble 2” and finally exoplanet characteriser as the new branch of astronomy arose in the late nineties.

A giant had been woken and filled with a terrible resolve.

The killer for JWST hasn’t been the optical telescope assembly itself, so much as folding up the huge attached sunshade for launch and then deploying it. That’s what went horribly wrong with “burst seams” in the latest round of tests and which continues to cause delays. Too many moving parts too – 168 if I recall. Moving parts and hard vacuums just don’t mix and the answer isn’t something as simple as lubricants, given conventional ones would evaporate in space, so that leaves powders, the limitations of which were seen with the failure of Kepler’s infamous reaction wheels. Cutting-edge a few years ago, these are now deemed obsolete for precision imaging telescopes, replaced instead by “microthrusters” – a technology that has matured quietly on the sidelines and will be employed on the upcoming ESA Euclid and then NASA’s HabEX.

From WFIRST to HabEX

The Wide Field IR Space Telescope, WFIRST is more by circumstance than design monolithic, and sadly committed to use reaction wheels, six instead of Kepler’s paltry four admittedly. I have written about this telescope before, but a lot of water as they say, has flowed under the bridge since then. An ocean’s worth indeed and with wider implications with the link as ever being exoplanet science.

To this end, any overview of exoplanet imaging cannot be attempted without starting with JWST and its ongoing travails, before revisiting WFIRST and segueing into HabEX. Then finally seeing how all this can be applied. I will do this by focusing an older but still robust and rather more humble telescope concept, EXCEDE.

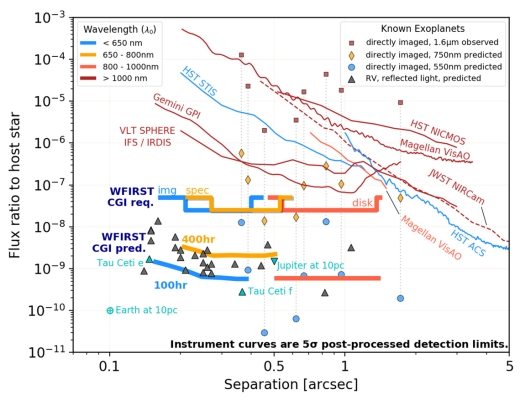

Reaction wheels – so long the staple of telescope pointing. But now passé, and why? Exoplanet imaging. The vibration reaction the wheels cause, though slight, can impact on the imaging stability even at the larger 200mas inner working angle (IWA) of the WFIRST coronagraph, IWA being defined as the nearest to the star that maximum contrast can be maintained. In the case of the WFIRST coronagraph this is 6e10 contrast (which has significantly exceeded its original design parameters already.

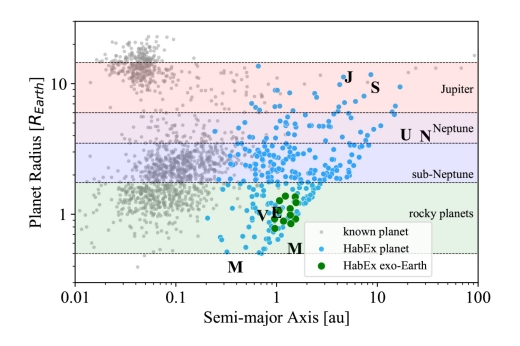

The angular separation of a planet from its star, or “elongation”, e, can be expressed as e = a/d, where a is the planetary semi-major axis expressed in Astronomical Units (AUs) and d is the distance of the star from Earth in parsecs (3.26 light years). By way of illustration, the Earth as imaged from ten parsecs would thus appear to be 100mas from the Sun – but would require a minimum 3.1m aperture scope to capture enough light and provide enough angular resolution of its own. Angular resolution of a telescope is its ability to resolve two separate points and is expressed as the related ? / D, where ? is the observation wavelength and D is the aperture of the telescope – in meters. So the shorter the wavelength and bigger the aperture, the greater the angular resolution.

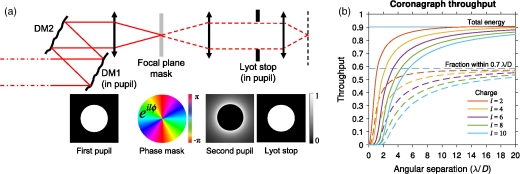

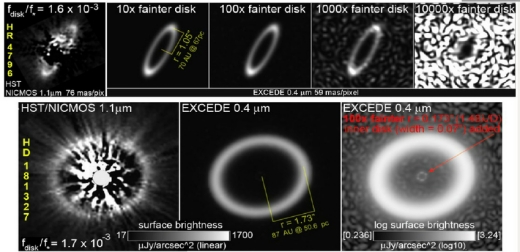

A coronagraph in the optical pathway will impact on this resolution according to the related equation n ? / D where n is a nominal integer set somewhere between 1 and 3 and dependent on coronagraph type, with a lower number giving a smaller inner working angle nearer to the resolution/diffraction limit of the parent telescope. In practice n=2 is the best currently theoretically possible for coronagraphs, with HabEX set at 2.4 ? / D. EXCEDE’s PIAA coronagraph rather optimistically aimed for 1 ? / D – currently unobtainable, though later VVD iterations or perhaps revised PIAA might yet achieve this and what better way to find out than via a small technological demonstrator mission?

This also shows that searching for exoplanets is best done at shorter visible wavelengths between 0.4 and 0.55 microns, with telescope aperture determining how far out from Earth planets can be searched for at different angular distances from their star. This in turn will govern the requirements determining mission design. So for a habitable zone imager like HabEX where n=2.4 and whose 4m aperture can search habitable zones of sun like stars out to a distance of about 12 parsecs. Coronagraph contrast performance varies according to design and wavelength so higher values of n, for instance, might still allow precision imaging further out from a star, perhaps looking for Jupiter/Neptune analogies or exo-Kuiper belts. Coronagraphs also have outer working angles, the maximum angular separation that can be viewed between a star and planet or planetary system (cf starshades,whose outer working angle is limited only by the field of view of the host telescope and is thus large).

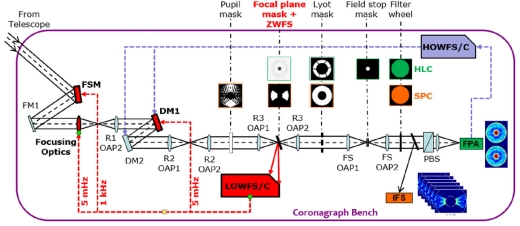

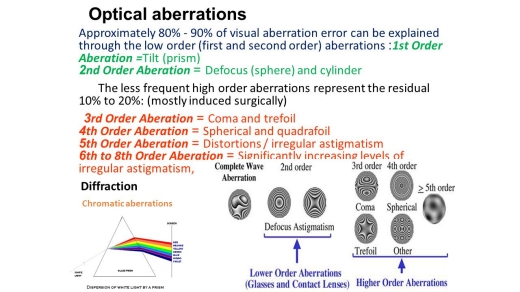

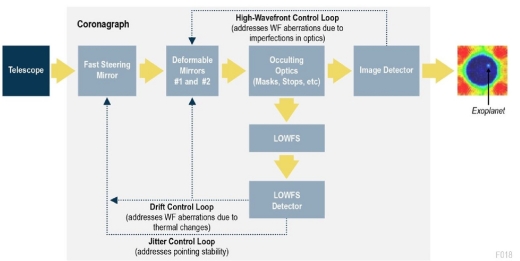

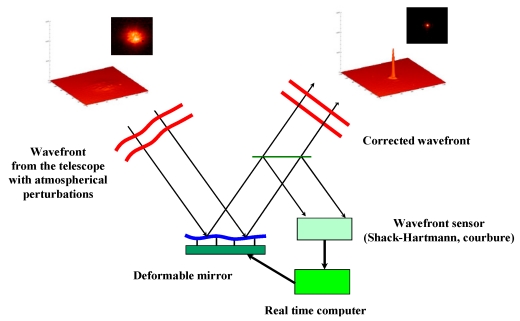

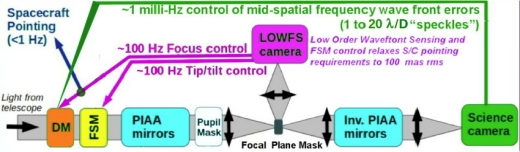

Any such telescope, be it WFIRST or HabEX, for success will require numerous imaging impediments to be adequately mitigated – so called “noise”. Noise from many sources: target star activity, stellar jitter, telescope pointing & drift. Optical aberrations. Erstwhile “low-order wavefront errors” – accounting for up to 90% of all telescope optical errors (ground and space) and including defocus, pointing errors like tip/tilt and telescope drift occurring as a target is tracked, due for instance to variations in exposure to sunlight at different angles. Then classical optical “higher order errors” such as astigmatism, coma, spherical aberration & trefoil – due to imperfections in telescope optics. Individually tiny but unavoidably cumulative.

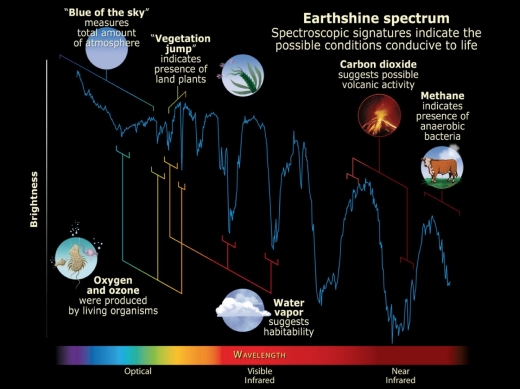

It cannot be emphasised enough that for exoplanet imaging, especially of Earth-mass habitable zone planets, we are dealing with required precision levels down to hundredths of billionths of a meter. Picometers. Tiny fractions of even short optical wavelengths. Such wavefront errors are by far the biggest obstacle to be overcome in high-contrast imaging systems. The image above makes the whole process seem so simple, yet in practice this remains the biggest barrier to direct imaging from space and from the ground even more.

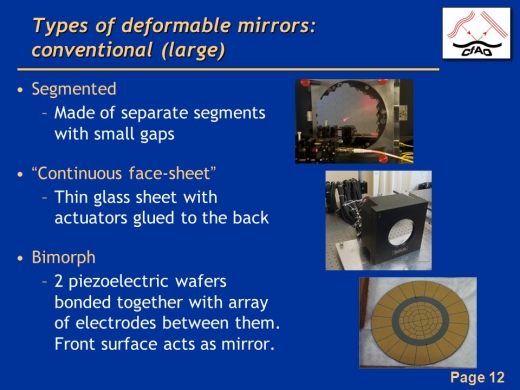

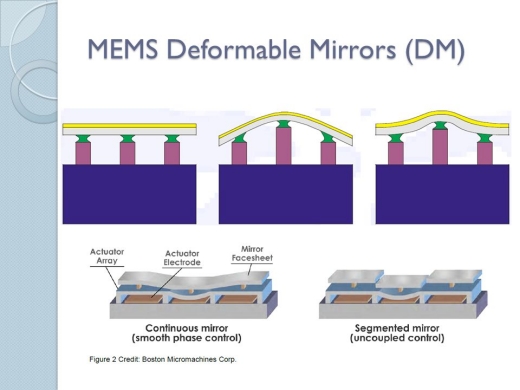

The delay between the (varying) wavefront error being picked up by the sensor, fed to the onboard computer and in turn the deformable modifying mirror to enable correction (along with parallel correction of pointing tip/tilt errors by a delicate “fast steering mirror”), and the precision of that correction – has been too lengthy. The central core of the adaptive optics (AO) system.

It has only been over the the last few years that there have been essential breakthroughs that should finally allow elegant theory to become pragmatic practice. This through a combination of wavefront correction via improved deformable mirrors and wavefront sensors and their enabling computer processing speed all working in tandem. This has led to creation of so-called “extreme adaptive optics” with the general rule that the shorter the observed wavelength, the greater the sensitivity “extremity” of the required AO. It is an even larger impediment on the ground where the atmosphere adds an extra layer of difficulty. These combine to allow a telescope to find and image tiny, faint exoplanets, and more importantly still, to maintain that image for the tens or even hundreds of hours necessary to locate and characterise them. Essentially a space telescope’s adaptive optics.

A word here. Deformable mirrors, fast steering mirrors, wavefront sensors, fine guidance sensors & computers, coronagraphs, microthrusters, software algorithms. All of these, and more, add up to a telescope’s adaptive optics – originally developed and then evolved on the ground, this instrumentation is now being adapted in turn for use in space. It all shares the feature of modifying and correcting any errors in wavefront of light entering a telescope pupil prior to reaching its focal plane and sensors.

Without it imaging via big telescopes would be severely hampered and the incredible precision imaging described here would be totally impossible.

That said, the smaller the IWA the greater the sensitivity to noise and especially vibration and line of sight “tip/tilt” pointing errors, and the greater the need for the highest performance, so called “extreme adaptive optics”. HabEX has a tiny IWA of 65 mas for its coronagraph (to allow imaging of at least 57% of all sun-like star hab zones out as far as 12 parsecs) and operates at a raw contrast as low as 1e11 – a hundred billionth of a metre!

Truly awesome. To be able to image at that kind of level is incredible frankly when this was just theory less than a decade ago.

That’s where the revolutionary Vector Vortex “charge” coronagraph (VVC) now comes in – the “charge 6” version still offers a tiny IWA but is less sensitive to all forms of noise – and especially the low wavefront errors described above – than other ultra high performance coronagraphs, noise arising from small but cumulative errors in the telescope optics.

This played a major if not pivotal role in the VVC 6 selection for HabEX. The downside (compromise) is that only 20% light incident on the telescope pupil gets through to the focal point instruments. This is where the unobscured largish 4m aperture of HabEX helps, to say nothing of removing superfluous causes of diffraction and additional noise in the optical path.

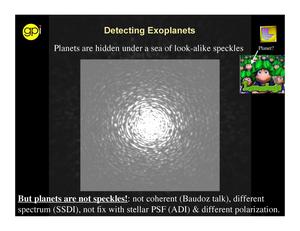

There are other VVC versions, the “charge 2” for instance (see illustration), that allows 70% throughput – but is so sensitive to noise as to be ineffectual at high contrast and low IWA. Always a trade off. That said, at the higher IWA (144mas) and lower contrast (1e8 raw) of a small imager telescope like the Small Explorer Programme concept EXCEDE, where throughput really matters, the charge 2 might work with suitable wavefront control. With a raw contrast (the contrast provided by the coronagraph alone) goal of < 1e8, "post-processing" would bring this down to the 1e9 required to meet the mission goals highlighted below. Post-processing involves increasing contrast post-imaging and includes a number of techniques with varying degrees of effectiveness that can increase contrast by up to an order of magnitude or more. For brevity I will mention only the main three here.

Angular differential imaging involves rotating the image (and telescope) through 360 degrees. Stray starlight, so called "speckles", are artefacts and move with the image.

A target planet does not, allowing the speckles to be removed, thus increasing the contrast. This is the second most effective type of post-processing. Speckles tend to be wavelength-specific, so looking at different wavelengths in the spectrum once again allows them to be removed with a planetary target persisting through various wavelengths. So-called spectroscopic differential imaging.

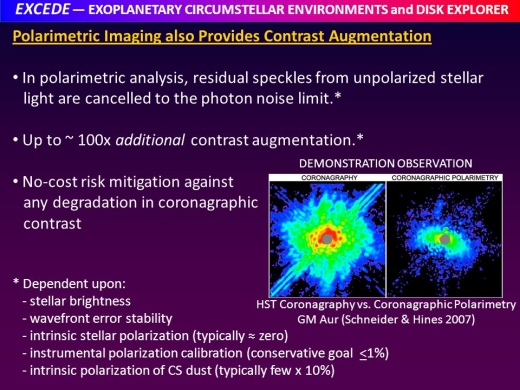

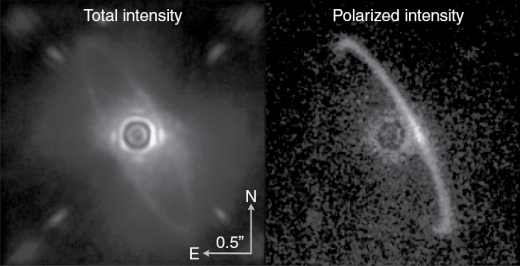

Finally, light reflected from a target tends to be polarised as opposed to starlight, and thus polarised sources can be picked out from background, unpolarised leaked starlight speckles with the use of an imaging polarimeter (see below).

Polarimetric differential imaging. Of the three, the last is generally the most potent and is specifically exploited by EXCEDE. Taken together these processes can improve contrast by at least an order of magnitude. Enter the concept conceived by the Steward Observatory at the University of Arizona. EXCEDE.

EXCEDE: The Exoplanetary Circumstellar Environment & Disk Explorer

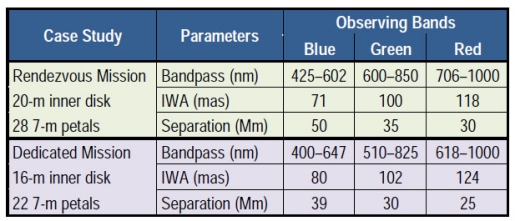

Using a PIAA coronagraph with a best IWA of 144 mas (?/D) and a raw contrast of 1e8, the EXCEDE (see illustration) proposal consisted of a three year mission that would involve:

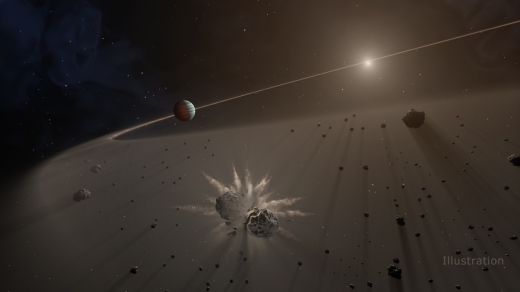

1/ Exploring the amount of dust in habitable zones

2/ Determining if said dust would interfere with future planet-finding missions – the amount of zodiacal dust in the Solar System is set at 1 “zodi”. Exozodiacal dust around other stars is expressed in multiples of this. Though a zodi of 1 appears atypically low, with most observed stellar systems having (far) higher values.

3/ Constraining the composition of material delivered to newly formed planets

4/ Investigating what fraction of stellar systems have large planets in wide orbits (Jupiter & Neptune analogues)

5/ Observing how protoplanetary disks make Solar System architectures and their relationship with protoplanets.

6/ Measuring the reflectivity of giant planets and constraining their compositions.

7/ Demonstrating advanced space coronagraphic imaging

A small and light telescope requiring only a small and cheap launcher to get it to its efficient but economic observation point in a 2000 Kms “sun synchronous” Low Earth Orbit – whereby the telescope would be in a near-polar orbit such that its position with respect to the Sun would remain the same at all points, allowing orientation of its solar panels and field of view to enable near continual viewing. Viewing up to 350 circumstellar & protoplanetary disks and related giant planets, visualised out to a hundred parsecs in 230 star systems.

The giant planets would be “cool” Jupiters and Neptunes located within seven to ten parsecs and orbiting between 0.5-7 AU from their host stars – often in the stellar habitable zone.

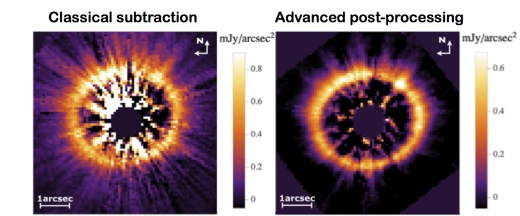

No big bandwidths, the coronagraph will image at just two wavelengths, 0.4 and 0.8 microns. Short optical wavelength to maximise coronagraph IWA and utilise an economic CCD sensor. The giant planets will be imaged for the first time (with a contrast well beyond any theoretical maximum from even a high performance ELT) with additional information provided via follow up RV spectroscopy studies – or Gaia astrometry for subsequent concepts. Circumstellar disks have been imaged before by Hubble but its older coronagraphs don’t allow anything like the same detail and are orders of magnitude short of the necessary contrast and inner working angle to view into the habitable zones of stars.

High contrast imaging in visual light is thus necessary to clearly view close-in circumstellar and protoplanetary disks around young and nearby stars, looking for their reaction with protoplanets and especially for the signature of water and organic molecules.

Exozodiacal light arises from starlight reflection from the dust and asteroid/cometary rubble within a star system, material that along with the disks above plays a big role in the development of planetary systems. It also acts as an inhibitor of exoplanetary imaging by acting as a contaminating light source in the dark field created around a star by a coronagraph with the goal of isolating planet targets. Especially warm dust close to a star, e.g in its habitable zone, a specific target for EXCEDE, whose findings could supplement ground-based studies in mapping nearby systems for this.

The Spitzer and Herschel space telescopes (with ALMA on the ground) both imaged exozodiacal light/circumstellar disks but at longer infrared wavelengths and thus much cooler and consequently further from their parent stars. More Kuiper belt than asteroid belt. Making later habitable planet imaging surveys more efficient as above a certain level of “zodis” imaging will be more difficult (larger telescope apertures allow for more zodis) with a median value of 26 zodis for a HabEX 4m scope. Yet another cause of background imaging noise – cf Solar System “zodiacal” light – which is essentially the same light visible within the Solar System (see illustration).

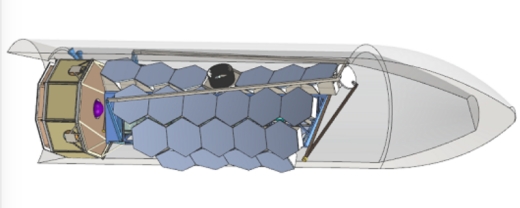

EXCEDE payload:

- 0.7m unobscured off-axis lightweight telescope

- Fine steering mirror for precision pointing control

- Low order wavefront sensor for focus and tip/tilt control

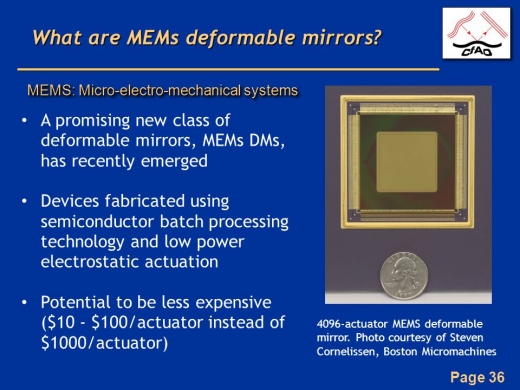

- MEMs deformable mirror for wavefront error control (see below)

- PIAA coronagraph

- Two band imaging polarimeter

EXCEDE as originally envisaged used a Phase Induced Amplitude Apodisation PIAA coronagraph (see illustration), which also has a high throughput ideal for a small 0.7m off-axis telescope.

It was proposed to have an IWA of 144 mas at 5 parsecs in order to image in or around habitable zones – though not any terrestrial planets. However, this type of coronagraph has optics that are very difficult to manufacture and technological maturity has come slowly despite its great early promise (see illustration). To this end it has to be for the time being superseded by other less potent but more robust and testable coronagraphs such as the Hybrid Lyot (see illustration for comparison) earmarked for WFIRST and more recently the related VVC’s greater performance and flexibility. Illustrations of these are available for those who are interested in their design and also as a comparison. Ultimately though one way or the other they block or “reject” the light of the central star and in doing so create a dark hole in the telescope field of view in which dim objects like exoplanets can be imaged as point sources, mapped and then analysed by spectrometry. These are exceedingly faint. The dimmest magnitude star visible to the naked eye has a magnitude of about 6 in good viewing conditions. A nearby exoplanet might have a magnitude of 25 or less. Bear in mind that each successive magnitude is about 2.5 times fainter than its predecessor. Dim!

Returning to the VVC, a variant of it could be easily substituted instead, without impacting excessively on what remains a robust design and practical yet relevant mission concept. Off-axis silicon carbide telescopes of the type proposed for EXCEDE are readily available. Light, strong, cheap and being unobscured, these offer the same imaging benefits as HabEX on a smaller scale. EXCEDE’s three year primary mission should locate hundreds of circumstellar/protoplanetary discs and numerous nearby cool gas giants along with multiple protoplanets – revealing their all important interaction with the disks. The goal is quite unlike ACEsat, a similar concept telescope, which I have described in detail before [see ACEsat: Alpha Centauri and Direct Imaging]. The latter prioritized finding planets around the two principal Alpha Centauri stars.

The EXCEDE scope was made to fit a NASA small Explorer programme $170 million budget, but could easily be scaled according to funding. Northrop Grumman manufactures them up to an aperture of 1.2m. The limited budget excludes the use of a full spectrograph, but instead the concept is designed to look at narrow visual spectrum bandwidths within the coronagraph’s etendue [a property of light in an optical system, which characterizes how “spread out” the light is in area and angle] that coincide with emission of elements and molecules from with the planetary or disk targets, water in particular. All this with a cost effective CCD-based sensor.

Starlight reflected from an exoplanet or circumstellar disk tends to be polarised, unlike direct starlight, and the use of a compact and cheap imaging polarimeter helps pick the targets out of the image formed at the pupil after the coronagraph has removed some but not all of the light of the central star. Some of the starlight “rejected” by the coronagraph is directed to a sensor that links to computers that calculate the various wavefront errors and other sources of noise before sending compensatory instructions to the optical pathway deformable mirrors and fast steering mirror to correct.

The all important deformable mirrors (manipulated from beneath by multiple mobile actuators) and especially the cheap but efficient new MEMs (micro-electro-mechanical mirrors) – 2000 actuators per mirror for EXCEDE, climbing to over 4096, or more, for the more potent HabEX. But yet to be used in space. WFIRST is committed to an older, less efficient “piezoelectric” alternative (more expensive) deformable mirror.

So this might be an ideal opportunity to show that MEMs work on a smaller, less risky scale with a big science return. MEMs may remain untested in space and especially the later more sensitive multi-actuator variety, but the more actuators, the better the wavefront control.

EXCEDE was originally conceived and unsuccessfully submitted in 2011. This was largely due to the immaturity of its coronagraph and related technology like MEMs at that time. The concept remains sound but the technology has now moved forward apace thanks to the incredible development work done by numerous US centres (NASA Ames, JPL, Princeton, Steward Mirror Lab and the Subaru telescope) on the Coronagraphic Instrument, CGI, for WFIRST. I am not aware of any current plans to resurrect the concept.

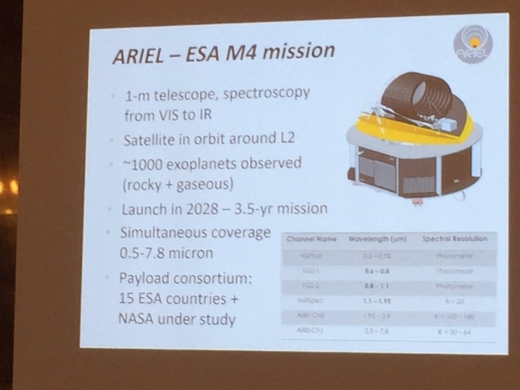

However the need remains stronger than ever and the time would seem to be more propitious. Exozodiacal light is a major impediment to exoplanet imaging so surveying systems that both WFIRST & HabEX will look at might save time and effort to say nothing of the crucial understanding of planetary formation that imaging of circumstellar disks around young stars will bring. Perhaps via a future NASA Explorer programme round or even via the European Space Agency’s recent “F class” $170 million programme call for submissions. Possibly in collaboration with NASA – whose “missions of opportunity” programme allows materiel up to a value of $55 million to supplement international partner schemes. The next F class gets a “free” ride, too, on the launcher that sends exoplanet telescopes PLATO or ARIEL to L2 in 2026 or 2028. Add in EXCEDE class direct imager and you get an L2 exoplanet observatory.

Mauna Kea in space if you will. By way of comparison, the overall light throughput of obscured WFIRST is just 2%!

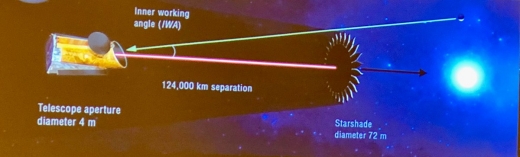

The 72m HabEX starshade has an IWA of 45 mas and a throughput of 100% (as does the smaller version proposed for WFIRST) and requires minimal telescopic mitigation/adaptive optics as for coronagraphs. This also makes it ideal for the prolonged observation periods required for spectroscopic analysis of prime exoplanetary targets, where every photon counts. Be it habitable zone planets with HabEX or a smaller-scale proof of concept for a starshade “rendezvous” mission with WFIRST.

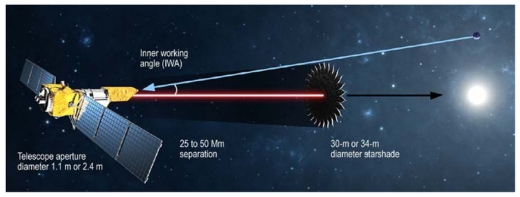

By way of comparison, the proposed EXO-S Probe Class programme (circa $1 billion) included an option for a WFIRST/Starshade “rendezvous” mission. This whereby a HabEX-like 30-34m self-propelled Starshade joins WFIRST at the end of its five year primary mission to begin a very much deeper three year exoplanet survey. Though considerably smaller than the HabEX Starshade, it also possesses the like benefits of high optical throughput (even more important on a non-bespoke obscured & smaller 2.4m aperture), a small Inner Working Angle (much less than with the WFIRST coronagraph), significantly reduced star/planet contrast and most important of all as we have already seen above, vastly reduced constraints on telescope stability & related wavefront control.

Bear in mind that WFIRST will still be using vibration-inducing reaction wheels for fine pointing. Operating at closer distances to the telescope than HabEX, the “slew” times between imaging would be significantly reduced too. This addition would increase the exoplanet return (both number and characterisation) many fold, even to the point of a small chance of imaging potentially habitable exoplanets. The more so if there have been the expected advances in performance of the software algorithms required to increase contrast post-processing (see above) and also to allow multi-star wavefront control that permits imaging of promising nearby binary systems (see below). Just a few tens of millions of dollars are required to make WFIRST “starshade” ready prior to launch and would keep this option open for the duration.

The obvious drawback with this approach is the long time required to manoeuvre into position from one target to the next along with the precision “formation flying” (stationed tens of thousands of kms from the starshade according to observed wavelength) required between telescope and starshade. For HabEX, this has a 250 km error margin in the back or forwards axis, but just 1m laterally and just one degree of starshade tilt.

So the observation strategy is done in stages. First the coronagraph searches for planets in each target star system over multiple visits, “epochs”, over the orbital period of the erstwhile exoplanet. This helps map out the orbit and increases chances of discovery . The inclination of any exoplanetary system in relation to the solar system is unknown – unless it closely approaches 90 degrees (edge on) and displays exoplanetary transits. So unless the inclination is zero degrees (the system sits face on to the solar system and lies in the plane of the sky like a saucer seen face on), the apparent angular separation between an exoplanet and its parent star will also vary across the orbital period. This might include a period during which it lies interior to the IWA of the coronagraph – potentially giving rise to false negative results. Multiple observation visits helps compensate for this.

Once the exoplanet discovery and orbital characteristics are constrained, starshade-based observations follow up. With its far larger light throughput (near 100%) the extra light available allows detailed spectroscopy across a wide bandwidth and detailed characterisation of high priority targets. For HabEX, this will include up to 100 of the most promising habitability prospects and some representative other targets. Increasing or reducing the distance between the telescope and the starshade allows analysis across different wavelengths.

In essence “tuning in” the receiver, with smaller telescope/starshade separations for longer wavelengths. For HabEX, this extends from UV through to 1.8 microns in the NIR. The coronagraph can characterise too if required but is limited to multiple overlapping 20% bandwidths with much less resolution due to its heavily reduced light throughput.

Of note, presumed high priority targets like the Alpha Centauri, Eta Cassiopiae and both 70 and 36 Ophiuchi systems are excluded. They are all relatively close binaries and as both the coronagraph and especially the starshade have largish fields of view, the light from binary companions would contaminate the “dark hole” around the imaged star and mask any planet signal. (This is also an issue for background stars and galaxies too, though these are much fainter and easier to counteract.) It is an unavoidable hazard of the “fast” F2 telescope employed – F number being the ratio of focal length to aperture. A “slower”, higher F number scope would have a much smaller field of view, but would need to be longer and consequently even more bulky and expensive. F2 is another compromise, in this case driven largely by fairing size.

Are you beginning to see the logic behind JWST a bit better now? As we saw with ACEsat, NASA Ames are looking to perfect suitable software algorithms to work in conjunction with the telescope adaptive optics hardware (deformable mirrors and coronagraph) to compensate for this (contaminating starlight from the off-axis binary constituent).

This is only at an early stage of development in terms of contrast reduction, as can be seen in the diagram above, but proceeding fast and as software can be uploaded to any telescope mission at any time up to and beyond launch.

Watch that space.

So exoplanetary science finds itself at a crossroads. Its technology is now advancing rapidly but at a bad time for big space telescopes with the JWST languishing. I’m sure JWST will ultimately be a qualified success and its transit spectroscopy characterisation of planets like those around TRAPPIST-1 will open the way to habitable zone terrestrial planets and drive forward telescope concepts like HabEX. As will EXCEDE or something like it around the same time.

A delay that holds up its successors both in time but also in funding. But lessons have been learned, and are likely to be out to good use. Just at the time that exoplanet science is exploding thanks to Kepler, and with TESS only just started, PLATO to come and then the bespoke ARIEL transit spectroscopic imager telescope to follow on. No huge leaps so much as incremental but accumulating gains. ARIEL moving on from just counting exoplanets to provisional characterisation.

Then onto imaging via WFIRST before finally HabEX and characterisation proper. But that will be over a decade or more away and in the meantime expect to see smaller exploratory imaging concepts capitalising on falling technology and launch costs to help mature and refine the techniques required for HabEX. To say nothing of whetting the appetite and keeping exoplanets formally where they belong.

But to finish on a word of perspective. Just twenty five years or so ago, the first true exoplanet was discovered. Now not only do we have thousands with ten times that to come, but the technology is coming to actually see and characterise them. Make no mistake that is an incredible scientific achievement as indeed are all the things described here. The amount of light available for all exoplanet research is utterly minuscule and the pace of progress to stretch its use so far is incredible. All so quick too. Not to resolve them, for sure (that would take hundreds of scopes operating in tandem over hundreds of kms) but to see them and scrutinise their telltale light. Down to Earth-mass and below and most crucially in stellar habitable zones. Precision par excellence. Maybe to even find signs of life. Something philosophers have deliberated over for centuries & “imagined” at length, can now be “imaged” at length.

At the forefront of astronomy, the public consciousness and in the eye of the beholder.

References

“A white paper in support of exoplanet science strategy”, Crill et al: JPL, March 2018

“Technology update”, Exoplanet Exploration Program, Exopag 18, Siegler & Crill, JPL/Caltech, July 2018

HabEX Interim report, Gaudi et al, August 2018

EXCEDE: Science, mission technology development overview, Schneider et al 2011

EXCEDE technology development I, Belikov et al, Proceedings of SPIE, 2012

EXCEDE technology development II, Belikov et al, Proceedings of SPIE, 2013

EXCEDE technology development III, Belikov et al, Proceedings of SPIE, 2014

“The exozodiacal dust problem for direct imaging of ExoEarths”, Roberge et al, Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, March 2012

“Numerical modelling of proposed WFIRST-AFTA coronagraphs and their predicted performances”, Krist et al, Journal of Astronomical Telescopes, Instruments & Systems, 2015

“Combining high-dispersion spectroscopy with high contrast imaging. Probing rocky planets around our nearest stellar neighbours”, Snellen et al, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 2015

EXO-S study, Final report, Seager et al, June 2015

ACESat: Alpha Centauri and direct imaging, Baldwin, Centauri Dreams, Dec 2015

Atmospheric evolution on inhabited and lifeless worlds, Catling and Kasting, Cambridge University Press, 2017

WFIRST CGI update, NASA ExoPag July 2018

“Two decades of exoplanetary science with adaptive optics”, Chauvin: Proceedings of SPIE, Aug 2018

“Low order wavefront sensing and control for WFIRST coronagraph”, Shi et al Proceedings of SPIE 2016

“Low order wavefront sensing and control..for direct imaging of exoplanets”, Guyon, 2014

Optic aberration: Wikipedia, 2018

Tilt (optics): Wikipedia, 2018

“The Vector Vortex Coronagraph”, Mawet et al, Proceedings of SPIE, 2010

“Phase-induced amplitude apodisation complex mask coronagraph tolerancing and analysis”, Knight et al, Conference paper: Advances in Optical and Mechanical Technologies for Telescopes and Instrumentation III, July 2018

“Review of high contrast imaging systems for current and future ground and space-based telescopes”, Ruane et al, Proceedings of SPIE 2018

“HabEX telescope WFE stability specification derived from starlight leakage”, Nemati, H Philip Stahl, Mark T Stahl et al, Proceedings of SPIE, 2018

Fast steering mirror: Wikipedia, 2018

The Essence of the Human Spirit: Apollo 8

I think of Apollo 8 in terms of transformation. As Al Jackson explains so well in the essay that follows, a lunar mission in December of 1968 seemed impossible for NASA and pushed technologies and procedures not yet tested into immediate action. But if Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders got Apollo back on its arbitrary and highly dangerous schedule, they did something as well for a college kid watching on TV that savage year. Seeing the crew’s images of the lunar surface and hearing their reading from Genesis on Christmas Eve knowing that their lives hung in the balance later that night turned me into an optimist. We must never devalue human accomplishment with the self-congratulatory irony so prevalent in the post-Apollo period. No, Apollo 8 was huge. It distilled our values of passion, courage and commitment, and its example will resonate long after we’ve sent our first probes to the stars.

By Albert Jackson

“Please be informed there is a Santa Claus”

— Jim Lovell (Post TEI December 25 1968)

“Sir, it wasn’t how you looked, it was how you smelled.”

— Navy Seal frogman to astronaut William Anders, explaining his reaction to opening the Apollo 8 capsule.

Author’s Personal Note: I was 28 years old in December 1968, and had aimed myself at space ever since reading the Collier’s magazine spaceflight series. The first issue was March 22 1952, when I was 11 years old. The series came to an end in the April 30, 1954 issue that asked ‘Can We Get to Mars?’ I was 13 then and remember Wernher Von Braun writing that it would take 25 years to get to Mars, I was downcast! That was too long. I came to the Manned Spacecraft Center in Jan 1966 and in time became an instructor for the Lunar Module training simulator. I did not train the Apollo 8 crew but I was in Building 4 Christmas Eve at a second floor small remote control room listening to the flight controller’s loop. It was very exciting, after Lunar Orbit Insertion, to hear acquisition of signal and confirmed orbit at approximately 4 am Houston time. I walked over to building 2 (building 1 these days) and got a cup of coffee. On the way back, I looked into a cold, about 35 deg F clear Houston night sky at a waxing crescent winter cold moon for about 15 minutes and thought wow! There are humans in orbit up there.

Making It Happen

Mandated with going to the moon before 1970 you have the following: a launch vehicle that has seventy anomalies on its last unmanned flight; three engines have failed; there are severe pogo problems; and the vehicle has yet to fly with a human crew. You have a spacecraft that has been re-engineered after a terrible disaster. You have a whole suite of on-board and ground software that has never been tested in a full non-simulation mission. You have a large ground tracking network not yet used to working a manned mission at the lunar distance. You have only four months to plan and train for a manned flight no one has ever done before. Four months out, the Pacific fleet was expecting a Christmas break, and no recovery ship might be available. The crew would have no Lunar Module ‘lifeboat’. No human had ever escaped the gravity of the Earth. Facing a terrible array of unknowns, your decision? ‘You’ are George Low, manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office. No hesitation… an orbital flight to the moon! [1, 2, 5]

Problems with achieving a lunar landing mission in 1969 made themselves manifest in the spring of 1968, when the delivery of the Lunar Module slipped. However, troubles with the Saturn V during the Apollo V launch test seemed on the way to solution by late spring. The concept of circumlunar flight goes back to Jules Verne, with the technical aspects laid out by Herman Oberth in 1923. In the 1960’s the flight planning documents for the Apollo program had laid out all the astrodynamics of the trajectory [7]. Problems with the Lunar Module looked as if the first moon landing might be pushed off into 1970.

Image: George Low with the iconic Wernher von Braun. Credit: NASA.

Placed against this, the Soviet Union was still actively pursuing a lunar landing, especially the possibility of a circumlunar flight in 1968. In April of 1968, both George Low of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC, later JSC) and Director of Flight Operations Chris Kraft started thinking about a lunar flight. By August of 1968, George Low decided the only solution to a lunar landing in 1969 was to fly to the moon before 1968 was out. [1, 2, 5]

The 9th of August 1968 was a very eventful day. Between 8:45 and 10 am, Low, Gilruth (MSC director), Kraft, and director of Flight Crew Operations Donald K. Slayton, after a breathless morning meeting at MSC, set up a meeting at Marshall Space Flight Center with its director Wernher von Braun, Apollo Program Director Samuel C. Phillips and Kennedy Space Flight Center director Kurt Debus at 2:30 pm that same day. At this meeting they finalized a plan to present to senior NASA management that if Apollo 7 were successful, Apollo 8 should not just go circumlunar but into lunar orbit in December of 1968. [1, 2, 5]

On that same August 9th, Slayton called Frank Borman and had him come to Houston from California and asked him if he wanted to go to the moon. He said yes, went back to California and told James Lovell and William Anders. They were enthusiastic. They all came back to Houston to start training. [1, 2, 5]

On August 15th, Deputy Administrator Thomas Paine, Director of the Apollo program, finally got approval from Administrator for Manned Space Flight George Mueller and NASA Administrator James Webb to move ahead with Apollo 8’s moon flight, contingent on the Apollo 7 mission. Therefore, before a manned version of the Command and Service Module had flown, a decision to go to the moon had been made. Planning and preparations for the Apollo 8 mission proceeded toward launch readiness on December 6, 1968. [1, 2, 5] {3], {4}.

Image: The crew: Jim Lovell, William Anders, and Frank Borman. Credit: NASA.

Critical Factors

On September 9, the crew entered the Command Module Simulator to begin their preparation for the flight. By the time the mission flew, the crew would have spent seven hours training for every actual hour of flight. Although all crew members were trained in all aspects of the mission, it was necessary to specialize. Borman, as commander, was given training on controlling the spacecraft during the re-entry. Lovell was trained on navigating the spacecraft in case communication was lost with the Earth. Anders was placed in charge of checking that the spacecraft was in working order. [1, 2, 5]

September, October and November of 1968 were three months of intense planning , training and work by the Mission Planning & Analysis Division (MPAD) {1}, Flight Crew Operations Directorate (FCOD) and Flight Operations Directorate (FOD). The Manned Spacecraft Center, Marshall Space Flight Center and the Kennedy Space Center had a lot on their plates! [1, 2, 5]

- Marshall had to certify the Saturn V for its first manned spaceflight. (8) {2}

- MPAD had to plan for the first manned vehicle to leave the earth’s gravitational field.

- MOD and FCOD had to plan and train for the first Lunar flight.

- MIT had to prepare for the first manned mission using a computer to perform guidance, navigation and control from the Earth to another celestial body.

- The various Apollo contractors had to prepare every hardware aspect of a Command Module for both transfer in Earth-moon space and orbit operations around the moon.

- The MSC Lunar scientists had to formulate a plan for photographic exploration of the moon from lunar orbit. The science community had to examine and plan for the radiation environment in trans Earth-Lunar space.

- KSC had to plan and train for the first manned Saturn V launch.

- MSC and Apollo contractors had to plan for the first ever hyperbolic re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere of a manned spacecraft.

That is just some of the problems to be solved!

Apollo 8 was a milestone flight for the Manned Space Flight Network (MSFN), since it was the first test of the network during a mission to the moon. Prior to the mission, concerns were raised regarding small terrestrial errors found in tracking tests that could be magnified to become much larger navigation errors at lunar distances. For assistance in the matter, MSC turned to JPL to look into their navigation system and techniques. JPL personnel, experienced in lunar navigation, proved very helpful as they assisted in locating tracking station location inaccuracies within Houston MCC software. These erroneous values would have manifested themselves as large tracking measurement errors at lunar distances. The tracking station location fixes were implemented less than two days prior to the launch of Apollo 8.

Of special note was Honeysuckle Creek near Canberra in Australia. It had a prime role for many of the first-time critical operations, acquisition of signal after Lunar Orbit Insertion, prime for post-Trans Earth Injection and prime for reentry. [3]

Image: Honeysuckle Creek station, famous for its role in receiving and relaying Neil Armstrong’s image from the lunar surface as he set foot on the moon in 1969, but equally critical in communicating with Apollo 8. Credit: Al Jackson.

Approval and Launch

The success of Apollo 7, flown October 11-22 1968, paved the way. On November 10 and 11th, NASA studied the Apollo 8 mission, approved it and made the public announcement on the 12th. {3}

Apollo 8 was launched from KSC Launch Complex 39, Pad A, at 7:51 a.m. EST on December 21 on a Saturn V booster. The S-IC first stage’s engines underperformed by 0.75%, causing the engines to burn for 2.45 seconds longer than planned. Towards the end of the second stage burn, the rocket underwent pogo oscillations that Frank Borman estimated were of the order of 12 Hz. The S-IVB stage was inserted into an earth-parking orbit of 190.6 by 183.2 kilometers above the earth.

Bill Anders later recalled:[4]

“Then the giant first stage ran out of fuel, as it was supposed to. The engines cut off. Small retro rockets fired on that stage just prior to the separation of the stage from the first stage from the second stage. So we went from plus six to minus a tenth G, suddenly, which had the feeling, because of the fluids sloshing in your ears, of being catapulted by — like an old Roman catapult, being catapulted through the instrument panel.

“So, instinctively, I threw my hand up in front of my face, with just a third level brain reaction. Well, about the time I got my hand up here, the second stage cut in at about, you know, a couple of Gs and snapped my hand back into my helmet. And the wrist string around my glove made a gash across the helmet faceplate. And then on we went. Well, I looked at that gash and I thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, I’m going to get kidded for being the rookie on the flight,’ because you know, I threw my hand up. Then I forgot about it.

“Well, after we were in orbit and the rest of the crew took their space suits off and cleaned their helmets, and I had gotten out of my seat and was stowing them, I noticed that both Jim and Frank had a gash across the front of their helmet. So, we were all rookies on that one.”

After post-insertion checkout of spacecraft systems, the S-IVB stage was reignited and burned 5 minutes 9 seconds to place the spacecraft and stage in a trajectory toward the moon – and the Apollo 8 crew became the first men to leave the earth’s gravitational field. [5]

The spacecraft separated from the S-IVB 3 hours 20 minutes after launch and made two separation maneuvers using the SM’s reaction control system. Eleven hours after liftoff, the first midcourse correction increased velocity by 26.4 kilometers per hour. The coast phase was devoted to navigation sightings, two television transmissions, and system checks. The second midcourse correction, about 61 hours into the flight, changed velocity by 1.5 kilometers per hour. [5]

Lovell [4] :

Well, my first sensation, of course, was “It’s not too far from the Earth.” Because when we turned around, we could actually see the Earth start to shrink. Now the highest anybody had ever been, I think, had been either—I think it was Apollo or Gemini XI, up about 800 mi. or something like that and back down again. And all of a sudden, you know, we’re just going down. And it was — it reminds me of looking — driving — in a car looking out the back window, going inside a tunnel, and seeing the tunnel entrance shrink as it gets — as you go farther into the tunnel. And it was quite a — quite a sensation to — to think about. You know, and you had to pinch yourself. “Hey, we’re really going to the moon!” I mean, “You know, this is it!” I was the navigator and it turned out that the navigation equipment was perfect. I mean, it was just — you couldn’t ask for a better piece of navigation equipment.”

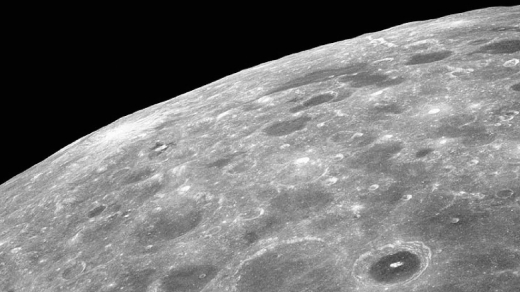

The 4-minute 15-second lunar-orbit-insertion maneuver was made 69 hours after launch, placing the spacecraft in an initial lunar orbit of 310.6 by 111.2 kilometers from the moon’s surface – later circularized to 112.4 by 110.6 kilometers. During the lunar coast phase the crew made numerous landing-site and landmark sightings, took lunar photos, and prepared for the later maneuver to enter the trajectory back to the earth. [5]

Image: Lunar farside as seen by Apollo 8. Credit: NASA.

Anders [4] :

“…That one view is sunk in my head. Then there’s another one I like maybe [and this is] of the first full Earth picture which made it again look very colorful. … [T]o me the significance of this [is that the moon is] about the size of your fist held at arm’s length … you can imagine … [that at a hundred arms’ lengths the Earth is] down to [the size of] a dust mote. [And, a hundred lunar distances in space are really nothing. You haven’t gone anywhere not even to the next planet. So here was this orb looking like a Christmas tree ornament, very fragile, not [an infinite] expanse [of] granite … [and seemingly of] a physical insignificance and yet it was our home…”

Borman [4]:

“Looking back at the Earth on Christmas Eve had a great effect, I think, on all three of us. I can only speak for myself. But it had for me. Because of the wonderment of it and the fact that the Earth looked so lonely in the universe. It’s the only thing with color. All of our emotions were focused back there with our families as well. So that was the most emotional part of the flight for me.”

Chris Kraft:

Anders: “Earthshine is about as expected, Houston.”

Kraft:” I shook my head and wondered if I’d heard right. Earthshine!” [1]

Christmas at the Moon

On the fourth day, Christmas Eve, communications were interrupted as Apollo 8 passed behind the moon, and the astronauts became the first men to see the moon’s far side. Later that day , during the evening hours in the United States, the crew read the first 10 verses of Genesis on television to earth and wished viewers “goodnight, good luck, a Merry Christmas and God bless all of you – all of you on the good earth.” [5]

On Christmas Day, while the spacecraft was completing its 10th revolution of the moon, the service propulsion system engine was fired for three minutes 24 seconds, increasing the velocity by 3,875 km per hr and propelling Apollo 8 back toward the earth, after 20 hours 11 minutes in lunar orbit. More television was sent to earth on the way back and, on the sixth day, the crew prepared for reentry and the SM separated from the CM on schedule. [5]

The Apollo 8 CM made the first manned ‘hot’ reentry at nearly 40,000 km/hr into a corridor only 42 km wide. Parachute deployment and other reentry events were normal. The Apollo 8 CM splashed down in the Pacific, apex down, at 10:51 a.m. EST, December 27 – 147 hours and 42 seconds after liftoff. As planned, helicopters and aircraft hovered over the spacecraft and para-rescue personnel were not deployed until local sunrise, 50 minutes after splashdown. The crew was picked up and reached the recovery ship U.S.S. Yorktown at 12:20 p.m. EST. All mission objectives and detailed test objectives were achieved. [5]

Borman [4]:

“We hit the water with a real bang! I mean it was a big, big bang! And when we hit, we all got inundated with water. I don’t know whether it came in one of the vents or whether it was just moisture that had collected on the environmental control system. … Here were the three of us, having just come back from the moon, we’re floating upside down in very rough seas — to me, rough seas.”

Borman[4]:

“Of course, in consternation to Bill and Jim, I got good and seasick and threw up all over everything at that point.”

Anders [4] :

“Jim and I didn’t give him an inch, you know, we [Naval Academy graduates] pointed out to him and the world, that he was from West Point, what did you expect? But nonetheless, he did his job admirably. But by now the spacecraft was a real mess you know, not just from him but from all of us. You can’t imagine living in something that close; it’s like being in an outhouse and after a while you just don’t care, you know, and without getting into detail… messy. But we didn’t smell anything…”

Christopher Kraft recalled in the Apollo oral history:[4]

“The firsts involved in Apollo 8 almost were unlimited, if you stop to think about it, from an educational point of view, from a theological point of view, from an aesthetic point of view, from an art point of view, from culture, I don’t know, you name it, that event was a milestone in history, which in my mind unless we land someplace else where there are human beings, I don’t think you can match it, from its effect on philosophy if you will, the philosophical aspects of that.”

Addendum: Where will the S-IV go?

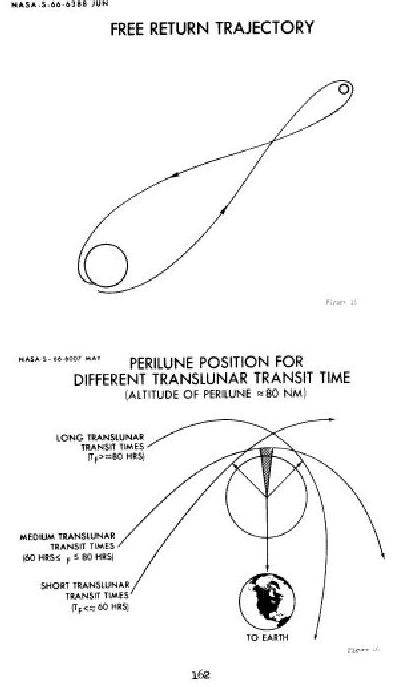

The Saturn V puts Apollo modules and SIVB in an Earth parking orbit. Then Trans Lunar Injection is performed, the Command Module is on a free return trajectory, meaning that if the Service Module engine fails, at any time, a safe return to the earth is possible (if the Service Module power system does not fail as happened with Apollo 13!)

A free-return trajectory is a path that uses the earth’s and the moon’s gravitational forces to shape an orbit around the moon and back to earth again. It’s called a “free-return” because it is, in essence, automatic. With some minor course corrections, a spacecraft will automatically be whipped around the moon, and will be on a trajectory that causes it to intercept the Earth’s. There is enough redundancy to do the final orbit shaping for correct reentry.

Marty Jeness of MPAD told me this story. He was at NASA headquarters in a meeting about free-return. He asked “Where does the S-IVB go?” After all, it also comes back to the Earth! No one had thought about this, but the possibility of a danger from impact on the earth is small It would most likely go into an ocean. To obviate any risk, the S-IVBs for Apollo 8, 10, and 11 made a tweak maneuver that placed them on a slingshot trajectory into solar orbit. (After Apollo 11, the S-IVB impacted the moon for seismic measurements, except that on Apollo 12 the burn misfired and that SIVB went into a solar orbit).

Footnotes

{1} Mission Planning and Analysis Division during Apollo was the first group to tackle the mission plan problems. An unusual group of men and women, they had to solve difficult astrodynamics problems that no one had ever seen before.

{2} Dieter Grau, Chief of Marshall’s Quality and Reliability Operations played a crucial role. It was thought that troubles with the Saturn V that had been uncovered in January of 1968 had been solved. The contractors had ok’d Apollo 8/AS-503. Von Braun sensed Grau’s unease and gave him permission to inspect the Saturn V centimeter by centimeter! After extra weeks of checking and rechecking, Grau and his people in the Quality and Reliability Laboratory finally gave the green light for the launch of Apollo 8.

{3} For the premier launch of a manned Saturn V, NASA prepared a special VIP list. The fortunate individuals on the list received an invitation in attractively engraved and ornate script: “You are cordially invited to attend the departure of the United States Spaceship Apollo VIII on its voyage around the moon departing from Launch Complex 39A, Kennedy Space Center, with the launch window commencing at 7 A.M. on December 21, 1968.” The formal card was signed “The Apollo VIII Crew” and included the notation, “RSVP.”

{4} Before Apollo missions had numbers they had letters. Owen Maynard, one of the engineers who had been designing manned spacecraft for NASA from the beginning, reduced the task of reaching the moon to a series of missions that, one by one, would push Apollo’s capability all the way to the lunar surface. These missions were assigned letters of the alphabet: A, B, C, D “… We kept the flight plans for these in a safe near my office. Since I had a clearance I used to look through these. Apollo 8 was really a ‘D’ mission, which was supposed to be a high Earth orbit mission. One subset was a circumlunar mission. I really did not expect that mission to take place. When Apollo 8 was announced we were surprised to find it had changed into a lunar orbiter mission.

{5} In late September 1968, we knew Apollo 8 was going to happen, but not when. I was surprised watching Walter Cronkite, I think in early October 1968, hearing that 8 was going in December!

References

(1) Kraft, Chris. Flight: My Life in Mission Control. Dutton, 2001

(2) Gene Kranz, Failure Is Not an Option, Simon and Schuster, 2001

(3) Hamish Lindsay, Tracking Apollo to the Moon, Springer, 2001

(4) Oral History Project, Johnson Space Center, 1997 – 2008 (Ongoing)

(5) Apollo 8 Mission Report, MSC-PA-R_69-1, February, 1969.

(6) Robert Zimmerman, Genesis: The Story Of Apollo 8, Basic Books, 1998.

(7) Apollo Lunar Landing Mission Symposium, June 25-27, 1966 Manned Spacecraft Center Houston, Texas

(8) Jeffrey Kluger, Apollo 8: The Thrilling Story of the First Mission to the Moon, Henry Holt and Co., 2017

An earlier version of this article appeared in the newsletter of the Houston Section of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics , AIAA Houston Horizons Winter 2008.

Looking Ahead

Centauri Dreams posts will unfortunately be sporadic over the next couple of weeks as I attend to some unrelated matters. But I do have several excellent upcoming articles already in the pipeline, including Al Jackson on Apollo 8 at the end of this week. Al, you’ll recall, was involved in Apollo as astronaut trainer on the Lunar Module Simulator, so his thoughts on the program’s extraordinary successes are always a high point.

Image credit: Manchu.

Ashley Baldwin, who knows the ins and outs of space-based astronomy better than anyone I know, will be looking at the key issues involved, with specific reference not only to WFIRST and HabEX but also a mission called EXCEDE, not currently approved but very likely the progenitor of something like it to come.

In early January, Jim Benford will be talking about beamed propulsion in a two-part article that looks to resolve key particle beam issues, with methods worked out by himself and the ingenious Alan Mole. There are all kinds of advantages to particle beaming but doing it without serious beam divergence is a problem we’ve addressed before. A possible solution emerges.

And, of course, we do have Ultima Thule coming up for New Horizons, on New Year’s Eve, no less. Data return including imagery will take some time, so we’ll be talking about the results throughout January. Emily Lakdawalla’s breakdown of the likely schedule gives an overview of the process.

Let me wish you all the best for the holidays. Here’s hoping for spectacular success for New Horizons along the way. Champagne and a working mission in the Kuiper Belt. What a night!