Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

A Fleet of Sail-driven Asteroid Probes

One of the great values of the Kepler mission has been its ability to produce a statistical sample that we can use to analyze the distribution of planets. The population of asteroids in our own Solar System doubtless deserves the same treatment, given its importance in future asteroid mining as well as planetary protection. But when it comes to main belt asteroids, we’re able to look up close, even though the number of actual missions thus far has been small.

Thus it’s heartening to see Pekka Janhunen (Finnish Meteorological Institute), long a champion of intriguing ‘electric sail’ concepts, looking into how we might produce just such an asteroid sampling through a fleet of small spacecraft.

“Asteroids are very diverse and, to date, we’ve only seen a small number at close range. To understand them better, we need to study a large number in situ. The only way to do this affordably is by using small spacecraft,” says Janhunen.

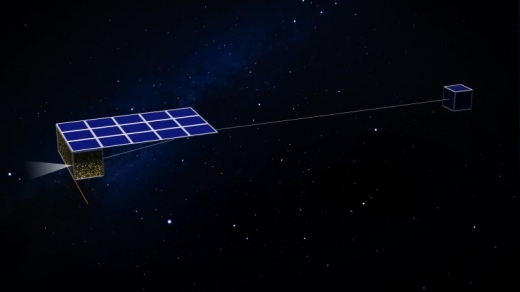

The concept weds electric sails riding the solar wind with a fleet of 50 small spacecraft, the intent being that each should visit six or seven asteroids, collecting spectroscopic data on their composition and taking images. Dr. Janhunen presented the idea at the European Planetary Science Congress (EPSC) 2017 in Riga on Tuesday September 19.

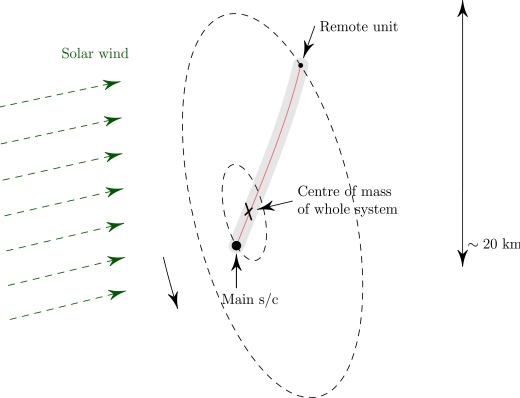

Image: The single-tether E-sail spacecraft. Credit: Janhunen et al.

Electric sails ride the solar wind, that stream of charged particles that flows constantly out of the Sun. While solar sails take advantage of the momentum imparted by photons on the sail, and beamed energy sails are driven by microwave or laser emissions, electric sails use the solar wind’s charged particles to generate all the propulsion they need without propellant. What Janhunen envisions is a tether attached to one end of a spacecraft, to which is attached an electron emitter and a high-voltage source, all connected to a remote unit at the other end.

The tether makes a complete rotation every 50 minutes, creating a shallow cone around a center of mass close to the primary spacecraft. Each small craft can change its orientation to the solar wind, and thereby alter its thrust and direction. Janhunen’s presentation at the EPSC made the case that a 5 kg spacecraft with a 20 kilometer tether could accelerate at 1 millimeter per second squared at the Earth’s distance from the Sun. Coupled with the boost provided by the launch itself, this is enough to complete a tour through the asteroid belt and return within 3.2 years.

Image: Artist’s concept of the spacecraft. Credit: FMI.

These spacecraft are small enough (Janhunen refers to them as ‘nanosats’) that they cannot carry a large antenna. Instead, the mission concept calls for each spacecraft to make a final flyby of the Earth to download mission data. The financial numbers are compelling. Billions of Euros would be involved in attempting a flyby of 300 asteroids with conventional methods, while Janhunen’s fleet of nanosats could, he believes, fly this mission for 60 million Euros.

The payoff could be substantial:

“The nanosats could gather a great deal of information about the asteroids they encounter during their tour, including the overall size and shape, whether there are craters on the surface or dust, whether there are any moons, and whether the asteroids are primitive bodies or a rubble pile. They would also gather data on the chemical composition of surface features, such as whether the spectral signature of water is present.”

Working with ever smaller payloads is a recurring theme in deep space exploration, the ultimate example being Breakthrough Starshot’s study of a laser-beamed sail mission to Proxima Centauri’s planet, one that would deploy a fleet of sails just meters to the side, each carrying a payload as small as a microchip. In Janhunen’s concept, the spacecraft are capable of carrying a 4-centimeter telescope capable of resolving asteroid surface features, along with an infrared spectrometer that can analyze reflected light to determine the object’s mineralogy.

With flybys at a range of about 1000 kilometers, the spacecraft would be able to image features to a resolution of 100 meters or better, and with multiple targets for each, the catalog of main belt asteroids that we have seen up close would suddenly mushroom. The mission, being referred to as the Asteroid Touring Nanosat Fleet, would help us catalog the various types of asteroids and provide valuable analysis of their composition and structure, all of which would add to our expertise if and when we ever have to nudge an asteroid into a new trajectory.

200,000 Euros per asteroid is a strikingly efficient use of resources, and the engineering involved in deploying Janhunen’s fleet of electric sails would give us priceless experience as we work with other mission concepts that involve the solar wind. But can we ride a wind as mutable and unpredictable as this one while ensuring the kind of pinpoint navigation we need? Questions like these will need answering in space through the necessary precursors.

‘Red Edge’ Biomarkers on M-dwarf Planets

When we think about the markers of possible life on other worlds, vegetation comes to mind in an interesting way. We’d like to use transit spectroscopy to see biosignatures, gases that have built up in the atmosphere because of ongoing biological activity. But plants using photosynthesis offer us an additional option. They absorb sunlight from the visible part of the spectrum, but not longer-wavelength infrared light. The latter they simply reflect.

What we wind up with is a possible observable for a directly imaged planet, for if you plot the intensity of light against wavelength, you will find a marked drop known as the ‘red edge.’ It shows up when going from longer infrared wavelengths into the visible light region. The red-edge position for Earth’s vegetation is fixed at around 700–760?nm. What we’d like to do is find a way to turn this knowledge into a practical result while looking at exoplanets. Where would we find the red edge on planets circling stars of a different class than our own?

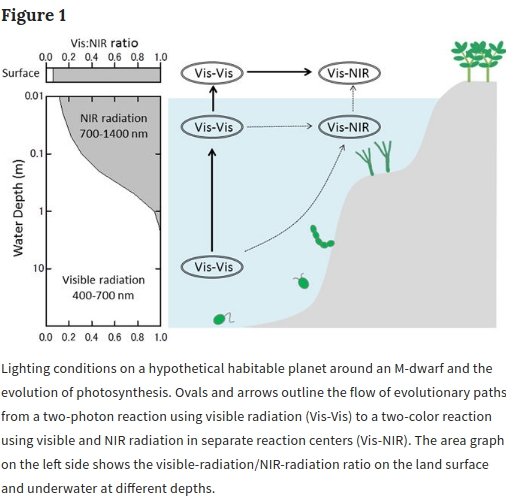

Led by Kenji Takizawa, researchers at the Astrobiology Center (ABC) of National Institutes of Natural Science (NINS) in Japan have taken up the question with regard to M-dwarfs. These stars have lower surface temperatures than the Sun and emit more strongly at near-infrared wavelengths than at visible wavelengths. Assuming vegetation in such an environment evolves to use the most abundant photons for photosynthesis, shouldn’t we expect the red edge to shift accordingly? Perhaps not, argue the authors, as only blue-green light penetrates beyond a few meters of water. Visible light, in other words, may play a larger role than we imagine.

This is a useful study, because we will begin our observations of possible biosignatures on exoplanets around stars like these, using not only upcoming space missions but ground observatories like the European Extremely Large Telescope, the Thirty Meter Telescope, and the Giant Magellan Telescope. The question is, what effect does the radiation of the star itself have on the red edge?

Image: Artist’s impressions of a habitable planet around M-dwarfs (left) and primordial Earth (right). Credit: ABC/NINS.

The authors believe that the first oxygenic phototrophs would have evolved underwater, using light at visible wavelengths. The star AD Leonis (AD Leo), an M-dwarf located 16 light years away, served as their model, with Takizawa and team plugging in a hypothetical planet of Earth’s size and insolation in orbit in the habitable zone there, allowing light conditions on the planet to be estimated and compared with solar irradiation on the Earth. The paper predicts ‘photosynthetic machineries’ that could emerge underwater and on land, and goes on to examine the question of land phototrophs evolving in the direction of infrared use from marine phototrophs that evolved in visible light.

From the paper:

After comparative investigations of light environments on the hypothetical habitable exoplanet around AD Leo and on the Earth, we conclude that two-photon reactions using visible radiation may first evolve in an M-dwarf planet’s ocean as oxygenic phototrophs. Reactions using NIR radiation may then evolve on the land surface. The first oxygenic phototroph is most likely to be established underwater about 10?m or deeper, and may expand its habitat to shallow water after the formation of an ozone layer and/or the cessation of UV emission from the active M-dwarf.

At depths of one meter and less, the authors believe, the abundance of near-infrared radiation may stimulate its evolutionary use, though notice what happened on Earth:

…phototrophs using NIR radiation are exposed to drastically changing light conditions in shallow water, which may be an obstacle to using NIR radiation before land colonization. The formation of the ozone layer on the Earth prior to the emergence of land plants enabled them to quickly colonize the land, safe from the effects of UV. A rapid transition from aquatic algae to land plants was accomplished without a change in the photosynthetic machinery.

Image: Figure 1 from the Takizawa paper. Credit: Takizawa et al.

The authors’ calculations show that green algae can adapt to M-dwarf radiation, though less productively than phototrophs using near-infrared radiation. Indeed:

…oxygenic photosynthesis could be driven by low-energy NIR radiation by improving the redox energy conversion efficiency and/or employing multi-photon reactions.

Thus it is possible that a ‘first wave’ of land plants could exhibit a red-edge position at 700–760?nm, as on the Earth. Using near-infrared radiation underwater would expose phototrophs to strong changes in light intensity and quality when they approach the water’s surface. That makes it more likely that adaptation to near-infrared would occur once on land, where the radiation spectral change is smaller.

To take these possible changes into account, astronomers need to look in a broad range when considering biomarkers on red dwarf planets:

…future missions should prepare to record surface spectra of habitable exoplanets at wavelengths from shorter than 700?nm to longer than 1,100?nm so that they have the capability to address the possibility that the red-edge position may change as the host M-dwarf ages.

The paper is Takizawa et al., “Red-edge position of habitable exoplanets around M-dwarfs,” Scientific Reports 7, No. 7561 (full text).

WASP-12b: A Low Albedo Planetary Torch

Sara Seager often describes the distribution of exoplanets as ‘stochastic,’ meaning subject to statistical analysis but hard to predict. A good thing, then, that Kepler has given us so much statistical data to work with, allowing us to see the range of possible outcomes when stars coalesce and planetary systems emerge around them. We’re not seeing copies of our own Solar System when we explore other stellar systems, but a variegated mix of outcomes.

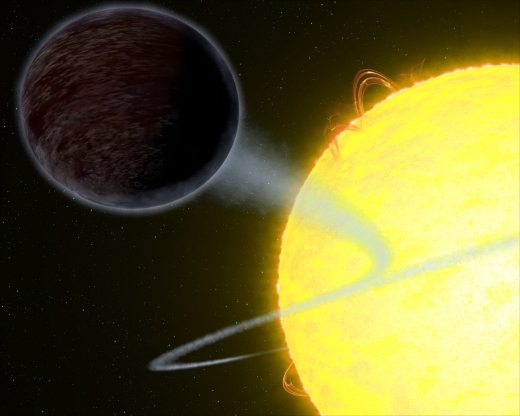

Thus finding a planet with an albedo as dark as fresh asphalt goes down as yet another curiosity from a universe that yields them in great abundance. The planet is WASP-12b, a ‘hot Jupiter’ of the most extreme kind. Previous work on this heavily studied world has already shown that due to its proximity to its host star, the planet has been stretched into an egg shape, while its day-side temperatures reach 2540 degrees Celsius, or 2810 Kelvin.

94 percent of incoming visible light here is trapped in an atmosphere so hot that clouds cannot form to reflect it. Hydrogen molecules are broken into atomic hydrogen, while alkali metals are ionized. The atmosphere resembles that of a low mass star instead of a planet, composed of atomic hydrogen and helium. Using Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph, the international team that produced this result, led by Taylor Bell (McGill University), has now measured an albedo of 0.064 at most, two times less reflective than our Moon.

Image: Twice the size of Jupiter, WASP-12b has the unique capability to trap at least 94 percent of the visible starlight falling into its atmosphere. Credit: NASA, ESA, and G. Bacon (STScI).

The planet’s radius is about twice Jupiter’s. The average hot Jupiter will reflect about 40 percent of incoming starlight, making WASP-12b a statistical outlier. But bear in mind that this planet’s proximity to its host star keeps it tidally locked, with one side always facing the star, the other always turned to space. That drops nightside temperatures well over 1000 degrees Celsius cooler, so that molecules can survive, producing possible clouds and hazes in the atmosphere.

Bell notes that the planet, orbiting about 3.2 million kilometers from its star, demonstrates that even among hot Jupiters the range of possibilities is surprisingly large:

“This new Hubble research further demonstrates the vast diversity among the strange population of hot Jupiters,” Bell said. “You can have planets like WASP-12b that are 4,600 degrees Fahrenheit and some that are 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit, and they’re both called hot Jupiters. Past observations of hot Jupiters indicate that the temperature difference between the day and night sides of the planet increases with hotter day sides. This previous research suggests that more heat is being pumped into the day side of the planet, but the processes, such as winds, that carry the heat to the night side of the planet don’t keep up the pace.”

1400 light years away in the constellation Auriga, WASP-12b circles a G-class star not dissimilar to the Sun, in an orbit lasting little more than a day. In addition to Hubble, the Spitzer Space Telescope and the Chandra X-ray Observatory have examined the system. Bell’s work with Hubble’s STIS examined the world by analyzing the combined light of star and transiting planet as WASP-12b passed behind the star. The scientists measured the albedo of WASP-12b at several different wavelengths. The lack of reflected light in the latter observations indicated that the day-side of the planet is absorbing almost all the starlight that falls onto it.

Back to that word ‘stochastic,’ which is reminding us that even when we look at a seemingly well-defined category of planet, our observations can yield wide differences. As the paper notes:

Our results are in stark contrast with those for the much cooler HD 189733b, the only other hot Jupiter with spectrally resolved reflected light observations (Evans et al. 2013); those data showed an increase in albedo with decreasing wavelength. The fact that the first two exoplanets with optical albedo spectra exhibit significant differences demonstrates the importance of spectrally resolved reflected light observations and highlights the great diversity among hot Jupiters.

Notice that reference to another well studied planet, HD 189733b. Results for the latter suggest that the planet has a deep blue color, while Bell’s team has shown that WASP-12b reflects no light at any wavelength. It does, however, emit light because of its high temperature. Think of a red hue, as this HST news release suggests, similar to hot glowing metal.

I might also note how, once again, we have a planetary system far different from our own. In addition to that hot Jupiter, WASP-12b’s host star is orbited by two M-dwarf companions that are bound in a binary system.

The paper is Bell et al., “The Very Low Albedo of WASP-12b from Spectral Eclipse Observations with Hubble,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 847, No. 1 (20 September 2017). Abstract / preprint.

Cassini: JPL Images at the End

Image: A monitor shows the status of NASA’s Deep Space Network as it receives data from the Cassini spacecraft, Friday, Sept. 15, 2017 in the Charles Elachi Mission Control Center in the Space Flight Operation Center at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky.

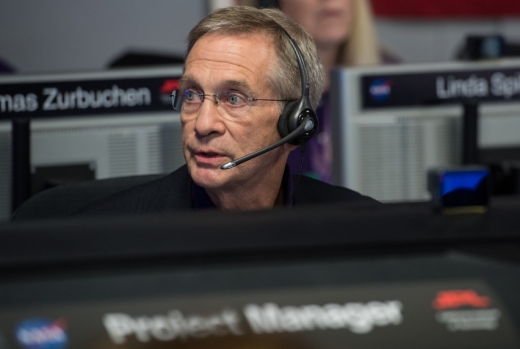

Image: Cassini program manager at JPL, Earl Maize, center row, calls out the end of the Cassini mission. Credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky.

Image: Cassini program manager at JPL, Earl Maize, left, and spacecraft operations team manager for the Cassini mission at Saturn, Julie Webster embrace after the Cassini spacecraft plunged into Saturn, Friday, Sept. 15, 2017 at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. At left is Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker. At right center is Jim Green, Director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

Image: Saturn’s active, ocean-bearing moon Enceladus sinks behind the giant planet in a farewell portrait from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. This view of Enceladus was taken by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft on Sept. 13, 2017. It is among the last images Cassini sent back. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

Image: This montage of images, made from data obtained by Cassini’s visual and infrared mapping spectrometer, shows the location on Saturn where the NASA spacecraft entered Saturn’s atmosphere on Sept. 15, 2017. This view shows Saturn in the thermal infrared, at a wavelength of 5 microns. Here, the instrument is sensing heat coming from Saturn’s interior, in red. Clouds in the atmosphere are silhouetted against that inner glow. This location — the site of Cassini’s atmospheric entry — was at this time on the night side of the planet, but would rotate into daylight by the time Cassini made its final dive into Saturn’s upper atmosphere, ending its remarkable 13-year exploration of Saturn. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

“Things never will be quite the same for those of us on the Cassini team now that the spacecraft is no longer flying,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at JPL. “But, we take comfort knowing that every time we look up at Saturn in the night sky, part of Cassini will be there, too.”

Thank You

For reminding us what technology can do. And what people can become.

Image: Members of the Cassini mission team. Cassini has benefited from the work of some 260 scientists at NASA, ESA and Agenzia Spaziale Italiana (ASI), as well as several European academic and industrial contributors. Credit: JPL/Caltech.

Cassini on Final Approach

Cassini mission engineers are referring to its final pass by Titan as ‘the goodbye kiss,’ a phrase that sounds like something from a Raymond Chandler novel. Maybe it’s the juxtaposition of intimacy and death that Chandler exploited so well. In any case, what counts in the last of Cassini’s hundreds of passes over Titan in its 13-year exploration of the system is the gravitational nudge that is sending the spacecraft into Saturn’s atmosphere tomorrow.

“Cassini has been in a long-term relationship with Titan, with a new rendezvous nearly every month for more than a decade,” said Cassini Project Manager Earl Maize at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “This final encounter is something of a bittersweet goodbye, but as it has done throughout the mission, Titan’s gravity is once again sending Cassini where we need it to go.”

Closest approach for the final pass at Titan occurred at 1504 EDT (1904 UTC) on September 12, at an altitude of 119,049 kilometers, with data streaming back to Earth containing science and trajectory information that confirms Cassini’s course for the Saturn atmosphere entry.

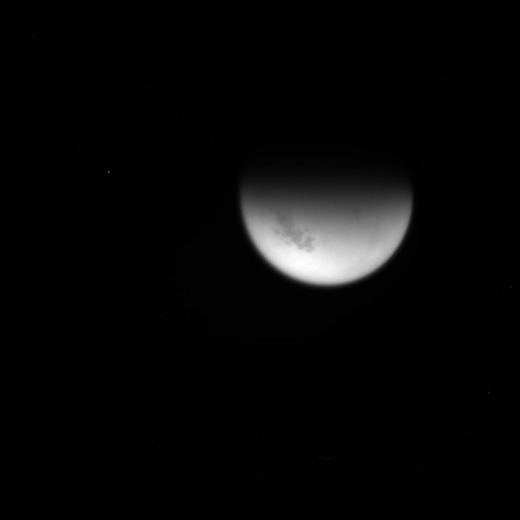

Image: One final look. This unprocessed image of Saturn’s moon Titan was taken by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft on Sept. 12, 2017. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

Loss of contact comes on September 15 at 0755 EDT (1155 UTC), about a minute after Cassini’s entry into the atmosphere at an altitude of 1915 kilometers above the cloud tops.

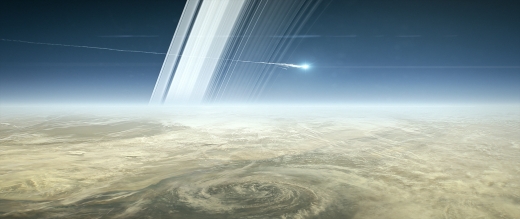

Moving at 113,000 kilometers per hour, Cassini will enter Saturn’s sky on the day side near local noon at about 10 degrees north latitude. Although the spacecraft’s attitude thrusters will begin firing to keep its high-gain antenna pointed at Earth, they’ll go from 10 percent to 100 percent of capacity within about a minute, fighting for stability and the maintenance of the all-important data link. Communications will end when the antenna loses its lock on the Earth, and the spacecraft should begin breaking apart within 30 seconds after the loss of signal.

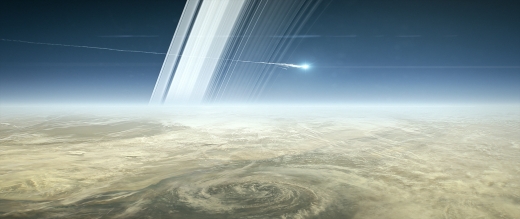

Image: NASA’s Cassini spacecraft is shown during its Sept. 15, 2017, plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere in this artist’s depiction. Cassini will use its thrusters to keep its antenna pointed at Earth for as long as possible while sending back unique data about Saturn’s atmosphere. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Coverage of the end of Cassini’s mission will be available live on NASA TV beginning at 0700 EDT (1100 UTC) tomorrow, the 15th — check here for information on coverage. And bear in mind with regard to the signal loss time I cited above that what we receive on Earth will have actually happened 83 minutes earlier, as JPL’s Maize reminds us:

“The spacecraft’s final signal will be like an echo. It will radiate across the solar system for nearly an hour and a half after Cassini itself has gone. Even though we’ll know that, at Saturn, Cassini has already met its fate, its mission isn’t truly over for us on Earth as long as we’re still receiving its signal.”

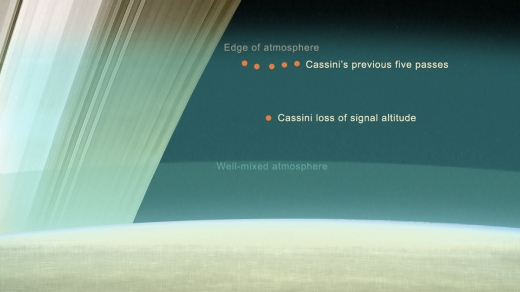

Image: Graphic showing the relative altitudes of Cassini’s final five passes through Saturn’s upper atmosphere, compared to the depth it reaches upon loss of communication with Earth. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

The spacecraft will be using eight of its 12 science instruments during the final approach, including all of its magnetosphere and plasma science instruments as well as its infrared and ultraviolet spectrometers. JPL is noting the importance of the Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer, which will be sampling the composition and structure of the atmosphere while being oriented in the direction of motion to produce the best possible sample.

A final set of views from Cassini’s imaging cameras will be transmitted to Earth today, with posting in unprocessed form beginning on the mission website around 2300 EDT (0300 UTC).

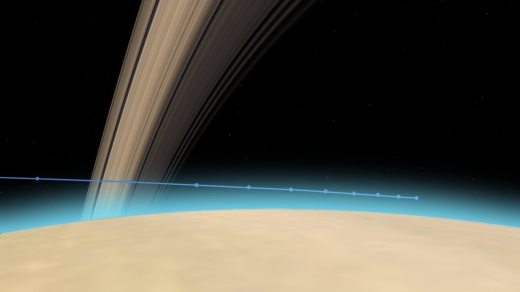

Image: Cassini’s path into Saturn’s upper atmosphere, with tick marks every 10 seconds. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

We’ve been talking about the end of this mission for a long time, but I do want to be sure you’re armed with the video link as well as the online toolkit for the final plunge. Social media addresses are https://twitter.com/CassiniSaturn and https://www.facebook.com/NASACassini, and you can keep an eye on #GrandFinale on Twitter as well.