Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Cassini as Atmospheric Probe

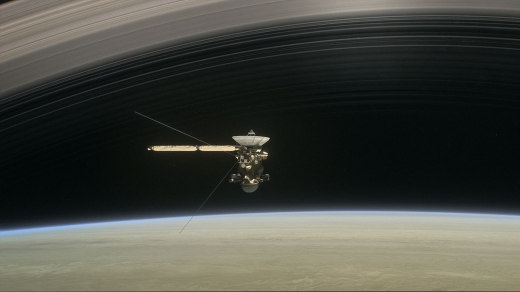

I’m going to miss the Cassini mission as much as anyone, but I have to say it’s fascinating to watch how mission controllers are wringing good science out of every last moment of the spacecraft’s life. We’re now in the Grand Finale phase of the mission, in which Cassini has moved between the planet and its rings in a series of weekly dives. Now we’re about to push into a new series of close passes, actually moving through Saturn’s upper atmosphere.

Notice the language that Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, uses to describe what’s next:

“As it makes these five dips into Saturn, followed by its final plunge, Cassini will become the first Saturn atmospheric probe. It’s long been a goal in planetary exploration to send a dedicated probe into the atmosphere of Saturn, and we’re laying the groundwork for future exploration with this first foray.”

Image: This artist’s rendering shows Cassini as the spacecraft makes one of its final five dives through Saturn’s upper atmosphere in August and September 2017. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Cassini as atmospheric probe? The mind boggles, but this will not be the first time the spacecraft has had to deal with an atmosphere. Those close flybys of Titan that produced so many spectacular findings about its atmosphere and surface required Cassini to use its rocket thrusters to maintain stability. You could consider the Titan flybys advanced preparation for this culminating act, and one in which the thrusters are being given wide margins for safety.

Consider the first atmospheric pass at Saturn, which will occur at 0022 EDT (0422 UTC) on Monday, August 14. The point of closest approach during these passes is to be between 1630 and 1710 kilometers above Saturn’s cloud tops. The built in margin is this: The thrusters are expected to operate somewhere between 10 and 60 percent of their capacity, the exact figure being determined by how stable the spacecraft remains through the procedure.

Anything beyond 60 percent means it proved harder to maintain stability than anticipated, a problem that would be corrected by a so-called ‘pop-up maneuver’ that will use the thrusters to increase the altitude of the later closest approaches by about 200 kilometers. Conversely, if no such maneuver is required, the orbit could be lowered as much as 200 kilometers on the last two orbits. In any case, a final ‘pop-down maneuver’ will occur on September 11, bending Cassini’s orbit (with the help of Titan) for the final plunge into the planet on September 15.

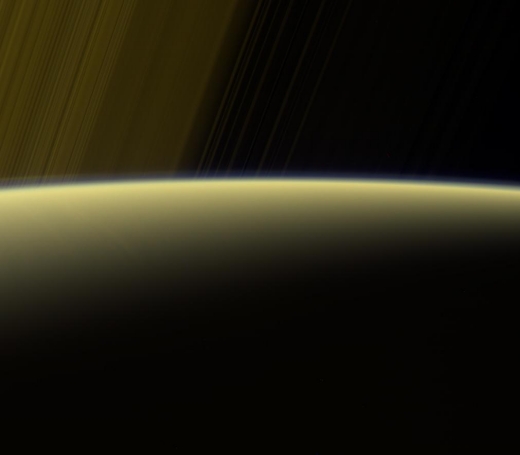

Image: This view from Cassini shows the narrow band of Saturn’s atmosphere, which Cassini will dive through five times before making its final plunge into the planet on Sept. 15. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

For now, we’ll be collecting data from Cassini’s ion and neutral mass spectrometer (INMS) to examine Saturn’s atmosphere, with other instruments producing high-resolution data on the planet’s auroras, atmospheric conditions and the vortices at the planet’s poles. Radar examination through the atmosphere should render features as small as 25 kilometers wide, about 100 times smaller than we’ve been able to obtain before the Grand Finale phase.

Cassini’s end on September 15 should be abrupt. With all seven of its science instruments reporting, the spacecraft will quickly reach an atmospheric density about twice what it should encounter during these final five passes. At that point, with the thrusters no longer able to maintain stability, Cassini’s antenna will lose its lock on Earth and we will lose contact.

Thinking about all that Cassini has given us, that’s a hard end to consider. But the spacecraft will be working until the last, augmenting the vast data flow we’ve received from Saturn. The discoveries we extract from Cassini’s mission will continue long after the probe is gone.

An Exoplanet with a Stratosphere

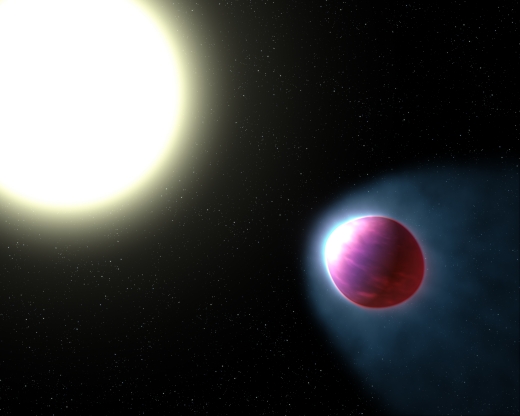

We’re beginning to find stratospheres on planets around other stars. A new study based at NASA Ames has looked closely at WASP-121b, a ‘hot Jupiter’ in its most extreme form. This is a planet about 1.2 times as massive as Jupiter, but with a radius almost twice Jupiter’s. The puffy world orbits its star in a scant 1.3 days (Jupiter, by contrast, circles the Sun every twelve years). As you would imagine, temperatures on WASP-121b are extreme, reaching 2500 degrees Celsius, which is enough to cause some metals to boil.

A stratosphere is simply a layer within an atmosphere where temperature increases with higher altitudes. Exactly how do scientists determine whether a planet fully 900 light years from Earth has such a layer? The answer is in the signature of hot water molecules, observed here by examining how these molecules in WASP-121b’s atmosphere react to specific wavelengths of light. The researchers used spectroscopic data from the Hubble instrument to make the call, knowing that cooler water vapor can block certain wavelengths from warmer layers below.

The brightness of the planet changes, in other words, at different wavelengths of light. When water molecules in the upper atmosphere are warmer than the layers below, as in a stratosphere, the molecules glow in the same infrared wavelengths that would be blocked by cooler air. The Ames team, led by lead author Tom Evans (University of Exeter) found exactly this signature in the Hubble data. Co-author Mark Marley (NASA Ames) describes the significance of the finding:

“This result is exciting because it shows that a common trait of most of the atmospheres in our solar system — a warm stratosphere — also can be found in exoplanet atmospheres. We can now compare processes in exoplanet atmospheres with the same processes that happen under different sets of conditions in our own solar system.”

Image: This artist’s concept shows hot Jupiter WASP-121b, which presents the best evidence yet of a stratosphere on an exoplanet. Credit: Engine House VFX, At-Bristol Science Centre, University of Exeter.

Heated to the point that iron exists in gaseous rather than solid form, WASP-121b offers an extreme form of the stratospheres we’ve observed in the Solar System. Earth’s stratosphere gains a heat assist from the ozone that traps the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation. But we also find stratospheres in the outer system. Both Jupiter and Titan have stratospheres, with methane the likely source of heating. The change in temperatures in Solar System stratospheres is generally small, in the neighborhood of 55 degrees Celsius. On WASP-121b, that figure is 560° Celsius.

Researchers have found evidence for stratospheres on some exoplanets, but the WASP-121b work is the first time that water molecules have provided such clear-cut evidence. The authors point to vanadium oxide and titanium oxide gases as possible heat sources here, playing the role that ozone does in Earth’s stratosphere as they absorb starlight at visible wavelengths in the same way that ozone does in the infrared. We’ll learn more about this as the observing effort, which will study 20 different exoplanets over 800 hours of Hubble time, continues.

“This new research is the smoking gun evidence scientists have been searching for when studying hot exoplanets. We have discovered this hot Jupiter has a stratosphere, a common feature seen in most of our solar system planets.” says co-author David Sing (University of Exeter). “It’s a truly exciting find as we’re seeing dramatic differences planet-to-planet which is giving valuable clues in figuring out how planets behave under different conditions, and we’re only just scratching the surface of all the new Hubble data.”

Further Hubble data, of course, will eventually give way to follow-up by the James Webb Space Telescope, delving deeper into the question of stratosphere behavior at different longitudes on the planet. It’s likely that, given its extreme conditions (any closer to its star and WASP-121b could be torn apart), this planet will become a benchmark for atmospheric models. It’s also certainly a reminder of how we’re learning not only to detect exoplanet atmospheres but probe them, an effort we hope to continue on smaller, potentially habitable worlds soon.

The paper is Evans et al., “An ultrahot gas-giant exoplanet with a stratosphere,” Nature 548 (3 August 3 2017). Abstract available. For related work, see Haynes, “Spectroscopic Evidence for a Temperature Inversion in the Dayside Atmosphere of the Hot Jupiter WASP-33b,” Astrophysical Journal Vol. 806, No. 2 (12 June 2015). Abstract.

Tuning Up Asteroid Threat Mitigation

Some people tell me that the dangers posed by an asteroid or comet impact on Earth are over-publicized. Surely whatever object hits us would land some place harmless, causing nothing but a flurry of news stories. Others remind me that Chelyabinsk was seriously rattled by the explosion of a small asteroid in 2013, an event that could have created appalling damage with a slight deviation in trajectory. My own view is that guessing at the odds doesn’t do much for us. I favor a strong research effort into asteroid deflection and risk mitigation strategies.

Normally planetary protection wouldn’t be high on the agenda on Centauri Dreams because I focus on deep space issues and our exploration possibilities far from Earth. But asteroid deflection merits our attention because I’m convinced it is one of the drivers for space research. Protecting the planet means learning not only how to deflect potentially risky objects but also how to detect them long before they pose a problem. The two work together in that some impactors could come from far out in the system and need long-term strategies.

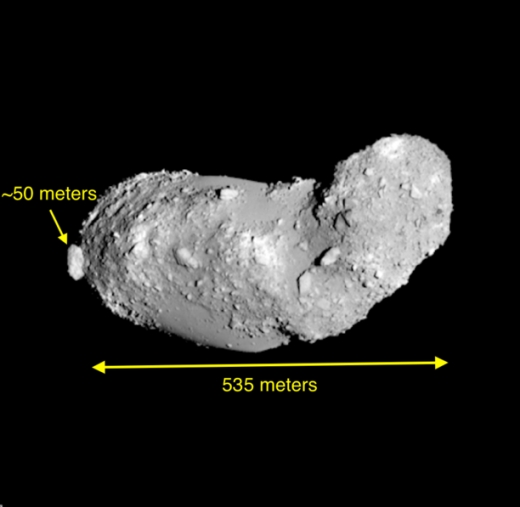

Thus I’m interested in learning that Vishnu Reddy of the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory is working with NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office, the federal entity in charge of coordinating efforts to protect Earth from hazardous asteroids, on an observational campaign to test how well our networked resources might respond to a threat. Unlike earlier, similar exercises, this one engages our response to an actual near-Earth asteroid known as 2012 TC4. The Chelyabinsk reference comes in handy here — 2012 TC4 is thought to be roughly the same size as the asteroid that lit up the Chelyabinsk sky in 2013.

Image: No photos of asteroid 2012 TC4 exist, but this image of Itokawa, another near-Earth asteroid, helps visualize its approximate size: next to Itokawa, which is half a kilometer long, TC4 would appear about the same size as the “bunny tail” feature visible on the left. Credit: JAXA.

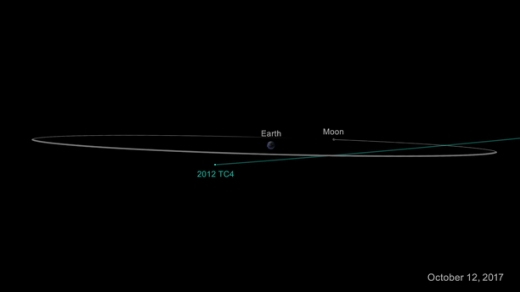

2012 TC4 was discovered by the Pan-STARRS 1 telescope on Oct. 5, 2012, at Haleakala Observatory (Maui). It is expected to pass as close as 6800 kilometers from the Earth on October 12 of this year. The idea of the exercise is to test systems involving observations, modeling, prediction and communications on an object that we can actually track.

When it becomes visible to Earth-based telescopes in early August, the asteroid’s orbit will need to be ‘recovered,’ meaning nailing down its parameters. Objects 50 meters across or less (about 12000 known near-Earth objects are larger than this) should disintegrate in the atmosphere, a heartening thought, though the 20-meter Chelyabinsk bolide, exploding high in the atmosphere, still resulted in thousands of injuries. The odds on a 1-kilometer or larger asteroid impacting the Earth are small, but exercises like this one will help test systems that one day might be called into play to evacuate an area where a small impactor might hit (see this interview with Paul Chodas, manager of the Center for Near-Earth Object Studies at JPL).

Image: On Oct. 12, 2017, asteroid 2012 TC4 will safely fly past Earth. Even though scientists cannot yet predict exactly how close it will approach, they are certain it will come no closer to Earth than 6,800 kilometers. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

More than a dozen observatories, universities and laboratories across the globe are involved in the upcoming 2012 TC4 flyby exercise. Let’s see how we do at pulling resources together to run an exercise on an actual flyby. Meanwhile, bear in mind that between 80 and 100 tons of various kinds of debris — dust, small asteroid fragments and so on — fall into the atmosphere every day.

Things falling down on us from above are, in other words, inevitable, but we’d like to know about the bigger stuff. Chelyabinsk-class events take place once or twice a century, but exactly when, given an NEO catalog that is incomplete, cannot always be predicted. Exercises like this one should help us tune up our response and suggest areas where we might improve.

Those other drivers for space exploration I mentioned earlier in today’s entry? To a large extent, they work in synchrony with asteroid mitigation. Astrobiology is clearly one, a search for the parameters of abiogenesis that dovetails with getting payloads to distant targets. An impact threat from further out in the Solar System than our population of near-Earth asteroids would demand proficiency at deep space propulsion and operations far from home. Add in the essential fact of human curiosity and the will to explore, and our push outward is sure to continue, whether with human crews or robotics, and despite inevitable budgetary constraints.

MU69 Occultations Yield KBO Data

Back in June we tracked what the New Horizons team was doing to refine our knowledge of 2014 MU69, the Kuiper Belt Object toward which New Horizons is now moving (see New Horizons: Occultations in Preparation for MU69). There were actually three of these events, on June 3, July 10 and July 17 of this year, studied not only by team members on the ground in Argentina and South Africa but by observatories like SOFIA (the airborne Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy) and the Hubble Space Telescope. Hubble and the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite were critical in calculating where the shadow of MU69 would fall.

Learning more about the distant KBO is a key part of the encounter, given the possibilities of debris around MU69 in the upcoming flyby. You’ll recall that the Pluto/Charon system was analyzed painstakingly in advance of the New Horizons flyby for the same reason. The occultations, in which the object passes in front of a distant star, allowed the team to take new readings on MU69, revealing that the KBO is no more than 30 kilometers long.

If, indeed, it is a single object. We may be dealing with what scientists involved with the project are calling an ‘extreme prolate spheroid’ (with an elongated, football-like shape (think American football as opposed to international). For that matter, we can’t rule out a binary, with two objects in close proximity or perhaps even touching (this is known as a contact binary).

“This new finding is simply spectacular. The shape of MU69 is truly provocative, and could mean another first for New Horizons going to a binary object in the Kuiper Belt,” said Alan Stern, mission principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado. “I could not be happier with the occultation results, which promise a scientific bonanza for the flyby.”

Image: One artist’s concept of Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69, the next flyby target for NASA’s New Horizons mission. This binary concept is based on telescope observations made at Patagonia, Argentina on July 17, 2017 when MU69 passed in front of a star. New Horizons scientists theorize that it could be a single body with a large chunk taken out of it, or two bodies that are close together or even touching. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Alex Parker.

But as we ponder the results from the occultations, consider just how successful the effort has been. We’re tracking the shadow of an object as it passes in front of a star, the object being 6.5 billion kilometers from the Earth. More than sixty observers dealt with high winds and cold to set up 24 mobile telescopes in the area of Chubut and Santa Cruz, Argentina on July 17. Amanda Zangari (SwRI), a New Horizons co-investigator and the first to see the signature of MU69 in the occultation data, exulted over the team’s success: “We nailed it spectacularly.”

It’s also heartening to see the level of public support for this work in the Argentine community of Comodoro Rivadavia. Local authorities closed a national highway for two hours to prevent car headlights from interfering with the observations, and nearby street lights were turned off to ensure darkness. Local residents parked trucks to serve as windbreaks.

Image: NASA’s New Horizons team trained mobile telescopes on an unnamed star (circled) from a remote area of Argentina on July 17, 2017. A Kuiper Belt object 4.1 billion miles from Earth – known as 2014 MU69 – briefly blocked the light from the background star, in what’s known as an occultation. The time difference between frames is 200 milliseconds, or 0.2 seconds. This data will help scientists better measure the shape, size and environment around the object. The New Horizons spacecraft will fly by this ancient relic of solar system formation on Jan. 1, 2019. It will be the most distant object ever explored by a spacecraft. Click here to see a longer version of the occultation. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/ Adriana Ocampo.

“This effort, spanning six months, three spacecraft, 24 portable ground-based telescopes, and NASA’s SOFIA airborne observatory was the most challenging stellar occultation in the history of astronomy, but we did it!” adds Alan Stern. “We spied the shape and size of 2014 MU69 for the first time, a Kuiper Belt scientific treasure we will explore just over 17 months from now. Thanks to this success we can now plan the upcoming flyby with much more confidence.”

So we proceed toward the most distant flyby in the history of space exploration, scheduled for January 1, 2019. A good deal of data analysis lies ahead for those studying the occultation results, but this most challenging ground occultation observation campaign in history has given us what we need. Be aware of the mission’s KBO Chasers page (and the hashtag #mu69occ) as you follow New Horizons’ next encounter online.

An Astrobiological Role for Titan’s Complex Chemistry?

Although Titan is often cited as resembling the early Earth, the differences are striking. Temperature is the most obvious, with an average of 95 Kelvin (-178 degrees Celsius), keeping water at the surface firmly frozen. Our planet was tectonically active in its infancy, roiled not only by widespread volcanism but also asteroid impacts, especially during the period known as the Late Heavy Bombardment some 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago.

Throw in the fact that the Earth had high concentrations of carbon dioxide — Titan does not — and it’s clear that we can’t make too broad a comparison between the two worlds. What we do have on Titan, however, is an atmosphere that teems with chemical activity, fueled by light from the Sun and the charged particle environment in the moon’s orbit around Saturn. So we do have a chemistry here that is capable of turning simple organics into more complex ones.

Thus the findings from a new study of archival data using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) are instructive. If we can rule out forms of life as we know them, we can’t exclude combinations that could only form in Titan’s frigid incubator. A potential marker of such chemistry is vinyl cyanide (acrylonitrile), which has been identified in the study and points in interesting directions.

Says lead author Maureen Palmer (NASA GSFC): “The presence of vinyl cyanide in an environment with liquid methane suggests the intriguing possibility of chemical processes that are analogous to those important for life on Earth.”

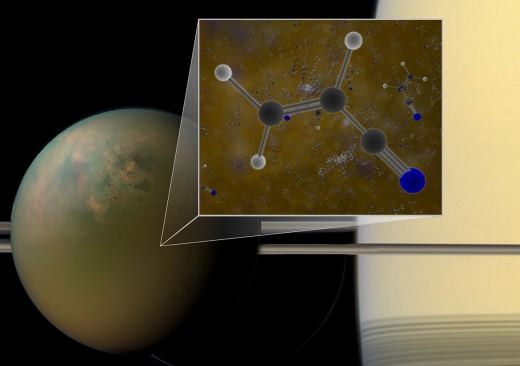

Image: Archival ALMA data have confirmed that molecules of vinyl cyanide reside in the atmosphere of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. Titan is shown in an optical (atmosphere) infrared (surface) composite from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. In a liquid methane environment, vinyl cyanide may form membranes. Credit: B. Saxton (NRAO/AUI/NSF); NASA.

An interesting thought, because the three signals Palmer and team found in millimeter wavelength spectra from ALMA observations in 2014 confirm what Cassini had already hinted at, which in turn reinforce laboratory simulations of Titan’s atmosphere. A surface rife with pools of hydrocarbons — and Titan is a place of methane rains, rivers and seas — could allow molecules of vinyl cyanide to link together, forming membranes that resemble the lipid-based cell membranes found on Earth. Titan’s complex organic molecules along with its nitrogen atmosphere and the presence of carbon-based molecules are provocative ingredients.

From the paper:

… lipid membranes, which are common to Earthly organisms, could not exist in cryogenic methane. Cell membrane-like compartments are crucial for the development of life from a sea of prebiotic reactants. These membranes enclose a small volume of solution, where reactants can be concentrated and (pre)biotic reactions can occur with greater frequency than they would in the dilute environment of an entire lake or sea. They also define individual cells as separate from each other, creating the potential for competition and natural selection.

And a nod to recent computational work on this matter:

Recent simulations have investigated some nitrile species for their potential to form flexible membranes in Titan-like conditions. These simulations suggest that vinyl cyanide (C2H3CN; also known as acrylonitrile or propenenitrile) would be the best candidate species for the formation of these hypothesized cell-like membranes, known as “azotosomes”

And now we have vinyl cyanide confirmed on Titan. At Cornell University, Jonathan Lunine worked with Paulette Clancy on a 2015 paper that discussed molecular simulation and its predictions as windows into prebiotic life conditions. Of the ALMA finding, Lunine says this:

“Researchers definitively discovered the molecule, vinyl cyanide (a.k.a. acrylonitrile), that is our best candidate for a ‘protocell’ that might be stable and flexible in liquid methane. This is a step forward in understanding whether Titan’s methane seas might host an exotic form of life. Saturn’s moon, Enceladus is the place to search for life like us, life that depends on — and exists in — liquid water. Titan, on the other hand, is the place to go to seek the outer limits of life — can some exotic type of life begin and evolve in a truly alien environment, that of liquid methane?”

And let’s not forget what else has been demonstrated by this work. What Lunine, Paulette Clancy and James Stevenson modeled in 2015 was exactly the kind of membrane we are now discussing. The finding of vinyl cyanide thus validates the authors’ 2015 paper, pointing to the value of molecular simulations as an adjunct to experimental and observational data.

The next steps? Further laboratory studies of the reactions involving vinyl cyanide. The authors point out that experimental work on membrane formation in cryogenic methane would help us determine just how viable a pathway this might be for astrobiology. We can also use infrared observations of Titan to study the transport of vinyl cyanide to the surface and map its spatial distribution, especially over the moon’s northern seas and lakes.

The paper is Palmer et al., “ALMA Detection and Astrobiological Potential of Vinyl Cyanide on Titan,” Science Advances Vol. 3, No. 7 (28 July 2017) (full text). The 2015 paper on modeling prebiotic environments is Stevenson, Lunine & Clancy, “Membrane alternatives in worlds without oxygen: Creation of an azotosome,” Science Advances Vol. 1, No. 1 (27 February 2015) (full text).

New Insights into Long-Period Comets

The Voyagers’ continuing interstellar mission reminds us of how little we know about space just outside our own Solar System. We need to learn a great deal more about the interstellar medium before we venture to send fast spacecraft to other stars. And indeed, part of Breakthrough Starshot’s feasibility check re small payloads and sails will be to assess the medium and determine what losses are acceptable for a fleet of such vehicles.

The definitive work on the matter is Bruce Draine’s Physics of the Interstellar and Intergalactic Medium, and thus it’s no surprise that Draine has been involved as a consultant with Starshot. As we saw yesterday, we have only one spacecraft returning data from outside the heliosphere (soon to be joined by Voyager 2), making further precursor missions explicitly designed to study ‘local’ gas and dust conditions a necessity.

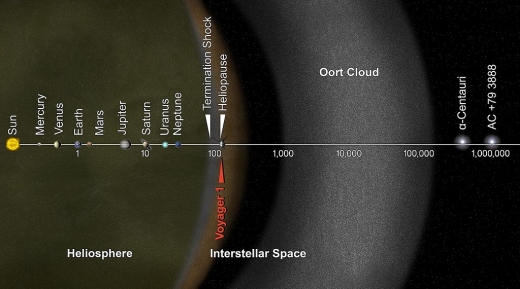

Another reminder of the gaps in our knowledge comes from an analysis of WISE data. The Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer satellite has given us a look at objects perturbed in some fashion within the Oort Cloud and now making occasional forays into nearby space. A distribution of comets and other icy bodies beginning some 300 billion kilometers from the Sun and extending outwards perhaps as far as 200,000 AU, the Oort Cloud’s extent makes it possible that it may extend into similar clouds of icy material around the Alpha Centauri stars.

Image: The fact that this image is logarithmic gives a startlingly clear idea of the extent of the Oort Cloud. The scale bar is in astronomical units, with each set distance beyond 1 AU representing 10 times the previous distance. One AU is the distance from the sun to the Earth, which is about 150 million kilometers. At the outer edge of the Oort Cloud, the gravity of other stars begins to dominate that of the sun. The inner edge of the main part of the Oort Cloud could be as close as 1,000 AU. Voyager 1, our most distant spacecraft, is around 125 AU. It will take about 300 years for Voyager 1 to reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud and possibly about 30,000 years to fly beyond it. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech.

There turns out to be more of such material than we had thought. The outer Oort Cloud is only loosely bound, meaning that gravitational interactions with passing stars or ‘rogue’ planets, not to mention effects from the Milky Way itself, can dislodge comets from their orbits and bring them into the inner system. Such comets may have periods not just in the hundreds but millions of years. The WISE data were gathered during the spacecraft’s primary mission, before its recommissioning as NEOWISE, with the charter of studying near-Earth objects.

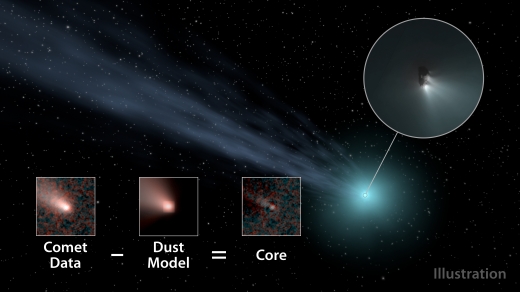

Measuring the size of long-period comets is difficult because the cloud of gas and dust around the comet — its coma — makes it difficult to measure the actual cometary nucleus. WISE was able to get around this problem by probing comets in the infrared, subtracting the glow of the coma from the signature of the nucleus. 2010 WISE observations of 95 Jupiter family comets — with periods of 20 years or less — and 56 long-period comets were used in the study.

The result: Comets that move regularly into the inner system are found to be, on average, as much as four times smaller than long-period comets, those moving only rarely near the Sun. Moreover, there are seven times more long-period comets in the size range of one kilometer in diameter and above than had previously been thought. In the eight months of the study period, three to five times more long-period comets were observed moving in the vicinity of the Sun than had been predicted.

“The number of comets speaks to the amount of material left over from the solar system’s formation,” said James Bauer, lead author of the study and now a research professor at the University of Maryland, College Park. “We now know that there are more relatively large chunks of ancient material coming from the Oort Cloud than we thought.”

Image: This illustration shows how scientists used data from NASA’s WISE spacecraft to determine the nucleus sizes of comets. They subtracted a model of how dust and gas behave in comets in order to obtain the core size. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

The results presumably reflect the fact that, coming closer to the Sun on a much more frequent basis, Jupiter-class short-period comets lose volatiles through sublimation, along with surface materials. An observed clustering in the orbits of long-period comets also suggests that many of these could have been part of larger bodies at some point in the past. The findings may have a bearing on our estimates of water delivery to the early Earth.

Co-author Amy Mainzer (JPL), principal investigator of the NEOWISE mission, points out that, traveling much faster than asteroids, long-period comets like these, many of them quite large, have to be factored into our analyses of impact risk. We’re developing an extensive catalog of near-Earth objects, but a long-period comet dislodged from the Oort Cloud, moving faster than any near-Earth asteroid, poses a risk that is badly in need of assessment.

The paper is Bauer et al., “Debiasing the NEOWISE Cryogenic Mission Comet Populations,” Astronomical Journal Volume 154, Number 2 (14 July 2017) (abstract). This NASA news release is also helpful.