Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Synchrony in Outer Space

As we watch commercial companies launching (and landing) rockets even as NASA contemplates a Space Launch System that could get us to Mars, it’s worth considering just which future we’re going to see happen. In this essay, Nick Nielsen thinks about making the transition between an early spacefaring civilization to a truly system-wide space culture, and one capable of moving still further out. No technologies arise in isolation, and the financial and social contexts of the things we do interact in ways that make predicting the long haul a dicey business. There is, as Nielsen reminds us, no unilateral history, but just how contingency and serendipity will shape what we achieve in space is no easy matter to untangle. Herewith some thoughts on history, context and attempts to put a brake on rapid change.

By J. N. Nielsen

Diachronic and synchronic historiography

In historiography a distinction is made between the diachronic and the synchronic, which is usually explained by saying that the diachronic is through time and the synchronic is across time. I don’t find this explanation helpful, so I say instead that the diachronic is succession in time and the synchronic is interaction in time. Of course, all interaction in time involves succession in time, so that a synchronic perspective involves some “width” of the present, thus in approaching history from a synchronic perspective we need to agree (even if only tacitly and implicitly) on the width of the present. [1]

The width of the present in synchronic historiography ideally could be set by any temporal parameters we choose. If we extrapolated from the punctiform present (an instantaneous present with no width) to ever-greater parameters for the present, mathematical induction would eventually lead us to a “present” that encompasses the whole of history. It could be argued that Big History is exactly this synchronic perspective that encompasses the whole of time, but I will not take this up at present, as I want to engage in a more conventional exercise in synchronic historical thinking that initially will take a period of a few decades—say, more than a decade but less than a century—as my temporal parameters, and then will be extended to a longer duration. However, I do want to add one highly unconventional element to synchronic historiography by applying this mode of historical thought not to the past, but to the future, though I will also reach a little bit into the past as well.

[“A perfectly scaled diagram showing the orbital altitudes of several significant satellites of earth. all planets and orbital distances are drawn to scale and the altitude data was collected from many Wikipedia articles and various other sites.” Image by Rrakanishu]

Origins of the Space Age

The Space Age began during the Cold War, and arguably as a technological spinoff of ballistic missile research. The first true ballistic missile was the German V-2 produced at the end of the Second World War, which was, for its time, a highly sophisticated rocket. The US and the USSR competed in scooping up the best German scientists after the war in order that these scientific minds should be put to work on the arms of the new superpowers that emerged from the war. Thus the Space Age was conceived in war and brought to its first successes in war. However, many within this war industry were visionaries who viewed their war work as a necessary evil in order to move humanity to the point at which military spinoff technologies could independently contribute to human progress (sort of like the idea of “Atoms for Peace”). Perhaps the best examples of this attitude are to be found in Wernher von Braun and Sergei Korolev.

After the US won the “Space Race” to get to the moon first, budgets for space exploration dwindled and less heroic space missions became the norm. One of the last Apollo capsules was employed in the Apollo-Soyuz mission, which linked up the US and the USSR spacecraft in orbit, and which initiated an era of international cooperation in space that has endured to the present day. Though this cooperative effort has been rocky at times, the funding of the effort has been kept sufficiently low that little has been at stake in terms of geopolitical-level goals. This sort of low-temperature, back-burner space effort could continue indefinitely with little to no impact upon the wider world.

The greatest geopolitical impact of the Space Age to date has been the ability to monitor Earth from orbit. The satellite industry is now an industry in every sense of the term. Many nation-states build and deploy satellites, and many different companies, both government SOEs and private industry, compete for the launch business to place satellites in orbit. The extent to which we today inhabit a planetary civilization—with all that implies in terms of both our global reach and our global limitations—is testified to by this satellite industry, which affects every other industry on the planet, as most of these satellites are built for the purposes of monitoring Earth and facilitating human activity on Earth. A planetary civilization in an equilibrium state thus extends a little beyond its homeworld, to include the orbital trajectories around its planet, in order to more effectively control, administer, and monitor that planetary civilization.

The greatest impact of the Space Age from a scientific point of view, but almost irrelevant from a geopolitical standpoint, has been the exponential improvement in our scientific knowledge of our solar system and the universe beyond by means of automated probes that have traveled throughout our solar system, and a little beyond, collecting data and transmitting it back to Earth. For a relatively small investment in contemporary terms, these instruments placed beyond the atmosphere of Earth, and in some cases on the surfaces of other planets in our solar system, have revolutionized cosmology and our understanding of the universe. While it is commonplace to belittle human achievement in the name of Copernicanism, it really is remarkable that we have managed to take the measurement of the universe entire while our species is still confined to a single planet.

[Alejo Fernández’s “Virgin of the Navigators” (1531-1536) vividly shows

the intersection of medieval Spanish piety and the new Age of Discovery.]

Extraterrestial buildout: the next developmental stage in spacefaring civilization

A planetary civilization more-or-less in an equilibrium state could continue in this manner, with a rudimentary presence in space, without moving appreciably beyond this level of spacefaring development. I take this rudimentary level of spacefaring to be consistent with a planetary civilization in its mature stage of development, when it is capable of satellite technology. However, if a planetary civilization begins to make the transition to a more robust spacefaring posture, it begins to exceed planetary equilibrium and begins the process of becoming a system-wide civilization within the planetary system of its homeworld. This will be the next developmental stage of our civilization if we choose to make that transition. I once called this process extraterrestrialization (which is, admittedly, a long and awkward word with many syllables), though now I prefer to call it “buildout.”

In the present context I will employ “buildout” as a general term meaning the building of any infrastructure that allows a civilization to make the transition to another stage of development. Thus the buildout of a transoceanic seafaring capacity was a necessary (but not a sufficient) condition to the Age of Discovery and the voyages of Columbus and Magellan. This buildout can also be thought of as the mature expression of the commercial trading networks of late medieval European civilization, at which point this regional civilization may have stagnated, though this stagnation did not in fact occur. The buildout of a rudimentary spacefaring capacity in the form of satellite technology can be thought of as the mature expression of a planetary civilization, but it also suggests the buildout of a more robust spacefaring capacity that is the necessary but not sufficient condition of a durable, self-sufficient human presence beyond Earth.

Buildout always shades over imperceptibly into that which comes next, but there is no inevitability as to what follows. [2] The intimations of future possibilities for civilization within the scope of our present institutions may remain undeveloped if a civilization stagnates at any one developmental stage. The spacefaring capacity we currently possess, enabling us to be active in Earth orbit, could hint at further spacefaring to come, or it could simply be the mature expression of a planetary civilization at equilibrium, needing this orbital capacity to monitor and manage the only world that it has. As Freud once said, sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

[We already have a blooming, buzzing confusion in Earth orbit as the result of all our satellites and space junk. This will only become more confusing over time.]

The blooming, buzzing confusion beyond Earth [3]

What I want to do here is to consider the buildout to the next stage of spacefaring civilization as the parameters of a “wide” present to be analyzed synchronically. This stage of spacefaring buildout will span from our present spacefaring capacity to a civilization on the threshold of an interstellar spacefaring capacity, but not yet having attained that goal. [4] The central lesson of a synchronic perspective on history is that social events do not occur in a social vacuum; technological developments do not occur in a technological vacuum; political events do not occur in a political vacuum, and so on. Moreover, these developments contextualize each other, so that social events also do not occur in a technological vacuum, political vacuum, etc.

Present spacefaring capacity includes satellite construction and launch, the construction and launch of scientific instruments destined for points throughout the Solar System, and a continual human presence in Earth orbit in the ISS since 02 November 2000. This human presence in LEO is a research station and not a settlement. The ISS is entirely dependent upon supply from Earth. There is no industrial infrastructure off the surface of Earth, whether an agricultural industry, or a manufacturing industry, or any other kind of industry, by which the ISS could even potentially support itself, either existentially or financially. [5]

The immediate future of spacefaring comprises both government and private sector initiatives that build on present spacefaring capacity, as well as plans for human missions to Mars. However, the immediate future is likely to be distinguished from the immediate past by the rapidly increasing private sector involvement in space. While private sector involvement in space is primarily driven by wealthy individuals who are engaged in aerospace for personal reasons rather than financial gain, the potential for financial gain, while largely unrealized, is present. The satellite launch industry is, as noted above, a true industry with competition among launch services, and no longer an exclusively government-sponsored undertaking. In so far as the reusable rockets of SpaceX and Blue Origin can bring down launch costs, these are potentially viable, profit-making businesses. Moreover, since the owners of these businesses engage in aerospace initiatives for personal fulfillment, it is likely that profit and growth in this sector will be re-invested in order to pursue more ambitious goals.

While I have great admiration for the work that Blue Origin and SpaceX have done in producing reusable rockets, and it seems likely that reusable rocket technology will reduce the cost of access to space as it matures, the engineering solutions brought to the problem by Blue Origin and SpaceX are not the only engineering solutions possible. There are not merely one or two different technologies that might be employed for cheaper access into space, there are quite literally dozens of different technologies with real promise in this field. I have previously addressed this in my Centauri Dreams post How We Get There Matters: the particular technologies we use will influence our spacefaring activities, because each technology has its individual possibilities and limitations. The actual technologies that come into routine use will be the result of a synchronic process that is ultimately as large and as complex as our industrial infrastructure that produces and uses the technology.

What this means is that technologies that enter into large-scale industrial production will be partially selected by what technology works best, and we don’t know what technology works best until we actually test these technologies under real-world conditions. But this isn’t the only influence on the process of bringing technologies to market. There will also be a question of financing, and which enterprise gets financed will partially be a function of the social and political network of the individuals involved in bringing technologies to market. If venture capitalists find you to be likeable and believable, you will probably get more funding than some other company whose founders are less likeable or less persuasive, even if the latter has a better product than the former. [6]

If a technology is not just an improvement of some degree, but an order of magnitude better than previous technologies [7], this technology will likely come into use at some point in time, but the industrialized economy has a remarkable ability to maintain non-optimal products in use—partly from social inertia, partly from risk aversion, partly from investor’s fear of financing stranded assets—as is witnessed by the QWERTY keyboard.

Synchronic interaction in markets

Energy markets are a perfect example of maintaining non-optimal technologies for social and economic reasons. We have the technology at present to supply the entire world with clean, non-polluting energy, but utilities continue to build fossil fueled power stations. The electrical generation industry changes very slowly, with the planning, financing, construction, and operation of generation facilities taking decades, and their decommissioning also spread over decades.

Energy markets are also a perfect illustration of synchrony in action; though they change slowly, they do eventually change in response to market forces. In my post Synchrony in Energy Markets I attempted to show the interaction of energy markets as technology changes and market forces interact with changes in human society. The failure to understand energy markets and how they function dynamically leads to fixations like the idea of “peak oil,” as though oil were the only fuel used, and the only fuel possible, for an industrialized economy, and as though technology never changes, never becomes more efficient, and industry never substitutes inputs or produces a different product. It would be possible for a totalitarian government to enforce the monopoly of a single fuel, and, to the extent that it was successful, it would weaken itself by making its economy vulnerable to competitors free to experiment with alternatives, which alternatives may prove to be more efficient or more effective.

Fuels are not only inputs of energy into an industrialized economy, fuels are also commodities, and commodities are traded on commodity markets. The same observation holds for the fixation on the dangers of fiat currencies, with the alternative being a currency based on some commodity, usually a durable metal, and this durable metal usually being gold. But gold (or silver) is a commodity like any other commodity, and, in an economic system of any degree of openness, will be traded. [8] Markets are not perfect, and are subject to manipulation and artificial limitation, but they do, on the whole and on the large scale, eventually bring supply and demand into equilibrium, and markets do this by efficiently allocating capital according to the signals conveyed by prices.

If you choose gold as the basis of your currency, then the discovery of a large gold mine in another nation-state, or the discovery of a new and more efficient way of refining gold (e.g., refining gold from seawater) will impact your economy in ways that you cannot control. If you have a gold-based currency and someone steers an asteroid into Earth orbit with more gold on it that is available to mine near the entire surface of Earth, as that gold is funneled into the terrestrial economy it will radically alter the commodity market for gold, and your gold-based currency will be impacted. You could try to limit this impact; you might even go to war with the extraterrestrial gold importer in order to try to control the flow of gold, but ultimately this is likely to be pointless. Market forces on a planetary scale are far stronger than any one nation-state. You might slow the transition to gold being plentiful, but you won’t stop it. If one gold importer is stopped, another, having learned hard lessons from the failure of the first, will do the same thing, but they will be smarter about it and harder to stop.

My point here is not to write an essay in economics, and I am not making any predictions, but rather I want to show the technologies of a spacefaring civilization in the context of the industrialized infrastructure that would produce them, and this industrialized infrastructure is dynamic, flexible, open to change, and, above all, multifarious. When a door closes, the saying goes, a window opens, and this is precisely what happens in an industrialized economy of planetary scale. Even legal limitations to commerce, backed by force of arms and penalties, will be circumvented by smugglers and black markets. As we know from sad experience, the very fact of a black market, by raising the penalty for failure, increases the price of banned commodities and so draws in competitors.

The examples of synchronic interaction in energy markets and currencies should give the reader a sense of the complexity of synchronic interactions that can also shape technologies, which, like energy and currencies, are commodities, but which are also tools that we employ in order to achieve some end, such as the buildout of spacefaring civilization. That these technologies are tools means that they will be employed to their best advantage in order to achieve some end; that these technologies are also commodities means that their employment will be measured against the employment of other technologies in competition with them.

[The tail fins of the 1959 Cadillac: glory days for Detroit.]

The problem of diachronic extrapolation

The simplest and most straight-forward way to construct a scenario for the future is a linear extrapolation of trends in the present. This is the fundamental conceit of induction: the future will be like the past. [9] Only, it won’t. Or, rather, the future won’t be exactly like the past. The extent to which we can interpret the future as being like the past defines the limits of inductive inference. Given the proper framework of scientific abstraction, this inductive extrapolation is unproblematic, but we aren’t always able to find the right framework, i.e., the best simplified model that captures the essential features while avoiding unnecessary complexity.

Diachronic extrapolation takes as its point of departure a single factor and extends into the future the apparent developmental trajectory of that single factor up to the present. The tendency of futurism to engage in single-minded diachronic extrapolation (something that I wrote about in The Problem with Diachronic Extrapolation and Diachronic Extrapolation and Uniformitarianism) magnifies an already human, all-too-human tendency to focus on a single factor, but the spacefaring future, if it comes about, will not be about a single technology, or a single industry, or about a single artificial habitat in Earth orbit, or a single settlement on Mars, or a single effort to reach the stars. All of these will be pursued simultaneously, and the technologies and engineering solutions that are developed will be found to interact and to be useful to each other in unexpected ways. Contingency and serendipity play a definitive role in the unfolding of history, and diachronic extrapolation by definition does not suggest contingent and serendipitous factors.

When someone (or some group of persons) is deeply invested in a single project, this personal investment becomes an impediment to understanding events divorced from this project, i.e., events that do not appear in the diachronic extrapolation of this project. The very fact that some individual has devoted their entire life to a single project makes them an expert judge on their area of specialization, but a poor judge of the big picture. Someone who invests their life in a project inevitably sees the world through the lens of that lifelong effort, and, while this is a valuable perspective, it involves a bias. Here a quote from James Madison is relevant: “No man is allowed to be a judge in his own cause, because his interest would certainly bias his judgment, and, not improbably, corrupt his integrity.” [10] We make an effort not to place individuals in the position of being a judge in their own cause because it is a moral hazard to do so, and we should exercise the same restraint in seeking an overview of the development of spacefaring civilization.

I do not wish to criticize or to belittle those who have invested their entire careers in a single area of expertise, largely limited to the production of single product. On the contrary, the plurality on which a large economy thrives only comes about as a result of dedicated groups of individuals who focus on their project to the exclusion of all other projects. We need to have dedicated industries around reusable rockets (like SpaceX and Blue Origin), hybrid engines (like Reaction Engines Limited), reusable space planes (like Sierra Nevada Corporation), Plasma engines (like Ad Astra Rocket Company), and more and better beside these efforts, but the future does not belong to any one of them alone. [11]

Processes that take place on a civilizational scale, and especially on the scale of planetary civilization, are intrinsically distinct from local efforts that focus on single industries or single technologies. I have observed elsewhere (cf. Detroit and Babylon) that Detroit in its heyday was a city based on a single product employing a single technology according to a single business model. This was one of the most successful industries in the middle of the twentieth century, but the product, the technology, and the business model all changed, and Detroit fell from a city of two million to a city of less than a million. If Detroit manages to build itself up again, this will not come about because of a renaissance in the American automobile industry, but because of some other product or service that arises from the social milieu of the city.

A diachronic extrapolation of Detroit’s economic success in the middle of the twentieth century, plotting the graph of its growth and tracing the same path into the future, would have given us Detroit as the largest and most successful city in the US, and a future of glorious chrome monstrosities, masterpieces in their own right, but not responsive to the social context in which they appear. When Detroit fell from its preeminence in post-war industrial production, that was not the end of civilization, but the end of the preeminence of a single city. A civilization consists of many cities, and different cities with different cultures produce different products by way of different business models.

What is true of a planetary-scale civilization will be true at a greater order of magnitude for a spacefaring civilization, and also for the buildout of a spacefaring capacity that will make a spacefaring civilization possible. If we take one technology or one industry and extrapolate its development into the future, the more we extrapolate, the more we will get the future wrong.

The more capacious and diverse futures imagined in Star Trek and Star Wars are closer to the reality of the synchrony of spacefaring, with many different space ships and many different robots, etc. These visions of a mature spacefaring future are often ridiculed as being a kind of naïve reflection of our present planetary civilization, but this kind of criticism fails to distinguish between the perennial and the ephemeral in history. We would expect that the future will take a form in which perennial verities of civilization are re-expressed in ephemeral terms, which latter will eventually be antiquated in their turn and replaced by further innovations that will continue to reflect the underlying intrinsic properties of civilization. If we could get into a time machine and visit a far future of a mature spacefaring civilization, some aspects of it would be strangely familiar us precisely because it grows out of familiar (and perennial) forces that manifest themselves in any large-scale social organization.

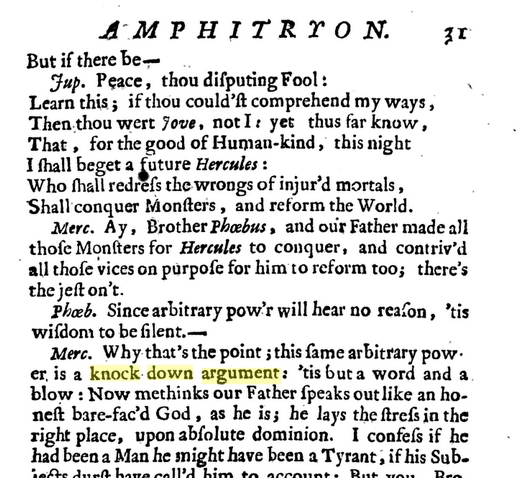

[A famous passage from Dryden’s Amphitryon; there are no knock-down arguments in history.]

There is no unilateral history

In addition to those who see the future through the lens of a single technology or a single industry, and so only see the future conditioned on that single factor, there are those who deny the possibility of large swathes of the future based upon a single factor taken to be a knock-down argument. When I have written posts about individual projects that might be pursued by, or which might develop from, spacefaring civilization, I have noticed that the comments often take these individual instances out of their (future) historical context and place them in splendid isolation, and then the project taken in isolation is subject to a critique conceived in isolation. Granted, it is necessary to place projects in isolation in order to subject them to a rigorous analysis, but if any of these projects come to fruition, they will come to fruition in a context of others projects in development and eventual implementation.

It is in the spirit of splendid isolation that it is said that human beings won’t settle Mars because conditions on Mars are more difficult than Antarctica or the Gobi Desert, and we haven’t settled these latter places (as though no legal impediments existed to settling the Gobi Desert), and that if we cannot even settle another terrestrial planet in our solar system, human beings have no future away from Earth (as if Mars were the only destination in space). It is said that human beings won’t live off Earth because there is no gravity in space and gravity on Mars (or the moon) is too weak and human beings cannot be healthy under these conditions (as though there were nothing that could be done about this), that it takes too long to get to Mars (as though transportation technology never changes), and, of course, the old, familiar line that we shouldn’t go into space when there is so much that remains to be done on Earth (as though going into space is going to make things worse on Earth, rather than better, contrary to evidence of the entire space program to date).

There is no single knock-down argument against a spacefaring future, just as there is no single technology or single industry that will determine the entire future course of history. There may well be single factors that are disproportionately difficult to resolve, and so disproportionately absorb energy and resources in pursuit of a solution, and there will almost certainly be single industries that dominate the effort for a time, but when considering something as complex as a civilization, and more especially the developmental trajectory of a civilization, no single factor will ever explain everything, and if a single factor explains a great many things at present, it will not continue to explain as many things in the future. As Fernand Braudel stated, “…we can no longer believe in the explanation of history in terms of this or that dominant factor. There is no unilateral history. No one thing is exclusively dominant…” [12]

[Walter Benjamin]

Walter Benjamin’s bombshell

When we understand synchrony in markets and social institutions, and that no single factor is exclusively dominant in the development of history, we understand why it is so disastrous for governments or other powers to put themselves in the position of picking winners and losers: they almost always make the wrong choices. We can, however, think of these mechanisms of top-down control, whether by governments or dominant industries, and their repeated record of making bad choices, as a social mechanism for slowing down economic growth and the disorienting social change that follows from rapid economic growth. There is a limit to the magnitude of social change that any society can absorb without experiencing catastrophic failure.

Walter Benjamin let slip a fascinating remark to this effect in a posthumously published fragment on one of his most famous late essays, “On the Concept of History” (a work that has significantly influenced my own thought). The collected papers of Benjamin include “Paralipomena to ‘On the Concept of History’,” and among these supplementary texts we find this bombshell:

“Marx says that revolutions are the locomotive of world history. But perhaps it is quite otherwise. Perhaps revolutions are an attempt by the passengers on this train—namely, the human race—to activate the emergency brake.” [13]

The Soviet Union embodied the ideology of which Benjamin was an apologist, and the Soviet Union presented itself to the world as a revolutionary new approach to industrialization that would transform the world in its image. While the western world was struggling with the Great Depression, the Soviet Union under Stalin was building entire cities from scratch, [14] and the modern graphics used to convey this message of socialist industrialization also presented the Soviet Union as being in the vanguard of history, an image driven home by the Soviet’s early successes in the Space Race. Under the glitz and the glamour, however, the Soviet project was more about exercising control over the direction of history and not allowing it to careen headlong into a chaotic future. This control came at a cost, and that cost was the Soviet economy eventually grinding to a halt. The emergency brake had been applied too suddenly and with too much pressure, and the result was a trainwreck.

Revolutionary and reactionary social and political movements alike can serve as an emergency brake on history, but this brake was applied more gently on the other side of the Iron Curtain. I have argued elsewhere (cf. Late-Adopter Spacefaring Civilization: the Preemption that Didn’t Happen), had funding for space exploration continued at the rate experienced during the Space Race that human civilization might have become spacefaring civilization in the second half of the twentieth century. It is often said that these Space Race levels of expenditure were ruinous, but I am not aware of any studies that show that even extravagant expenditures on space exploration have negatively impacted terrestrial events, while numerous studies have shown the spinoff benefits of the space program for terrestrial civilization. However, one can easily imagine that the rapid social change that would have followed from the early emergence of spacefaring civilization, following so closely on the heels of the industrial revolution, might have been more than western civilization could have borne without cracking. And so the emergency brake was applied, and instead of careening into an unknown future, we retreated to the certainties of life on Earth. Spacefaring civilization had to wait.

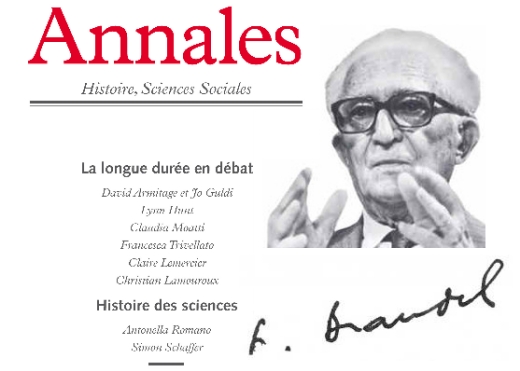

[Fernand Braudel made the Annales school of historiography prominent and emphasized the study of the longue durée.]

The longue durée of early spacefaring civilization

While it could have started earlier, but is only now on the horizon, the buildout of a robust spacefaring infrastructure will in any case require centuries to come to maturity, and several centuries of unified development like this is an appropriate period to study in terms of the longue durée. The idea of the longue durée is essentially that of treating an entire macrohistorical period [15] in terms of synchrony (though this is not how Braudel, who brought the idea to prominence, formulated the longue durée). It is often said that journalists write the first draft of history. If this is true, then we can think of the longue durée as the final draft of history, purged of the breathless onrush of events, having risen above mere contingency and party faction alike, with, “…all the heavy thickness of social reality, resistant to all inclemency, to crises and sudden shocks…” [16]

As the buildout of early spacefaring civilization unfolds, the developments that constitute this buildout will occur in the context of other developments occurring simultaneously, and these developments will shape each other as they interact. Individual human beings and human institutions will, in turn, react to these developments as they occur, and these actions and reactions will constitute the background for further developments. In contradistinction to the diachronic perspective, which takes a single factor and extrapolates beyond the present from this point, the synchronic perspective places the same single factor in the context of other such factors. The interaction that synchrony studies is the sum total of every possible diachronic extrapolation overlapping and intersecting with every other extrapolation. The furthest extent to which we can push this synchronic interaction is the longue durée.

Needless to say, the development of spacefaring civilization will also take place against the background of continuing developments of terrestrial civilization, with all that this entails for continuity: both the timeless verities of the human condition, in its geographical and biological context, and the unprecedented social developments of the fulfillment of planetary industrialized civilization, which latter can also be studied in terms of the longue durée. The synchrony of terrestrial developments will overlap with the synchrony of extraterrestrial developments, as the longue durée of planetary civilization will overlap with the longue durée of early spacefaring civilization.

We can think of synchronic historiographies of planetary civilization and early spacefaring civilization as a kind of temporal or historical form of Copernicanism. As the Copernican principle reminds us that the Earth is a planet among other planets, the sun a star among other stars, and the Milky Way a galaxy among other galaxies, the synchronic perspective on history reminds us that any given event is an event among other events, that any given technology is a technology among other technologies, and so on. We might, then, call the present effort an attempt at Copernican historiography, and Copernican historiography teaches us the importance of displacing any one perspective from the center of our concern, including any perspective entailed by seeing development through the exclusive lens of a single technology. The perspective of the longue durée facilitates our ability to understand history in this way, because we are not focusing on individual events, persons, or technologies, but on a complex structure in time that constitutes a macrohistorical period.

Beyond synchrony: the axes of historiography

In my paper A Manifesto for the Scientific Study of Civilization I wrote:

“One form that the transcendence of an exclusively historical study of civilization can take is that of extrapolating historical modes of thought so that these modes of thought apply to the future as well as to the past (and this could be called history in an extended sense). To recognize the role of the future in the concept of civilization is not intended to call into question the value of history and tradition, but to supplement it, and to supplement the concept of civilization with the idea of its future is to pass beyond history sensu stricto.”

The present essay on synchrony in early spacefaring civilization is an attempt to put this principle into practice; it has been my purpose to employ traditionally historical modes of thought in order to explicate the future. I have here focused on synchrony because I wanted to make a particular point about focusing on particular technologies of spacefaring in isolation, but a comprehensive study of early spacefaring civilization would not be limited to synchrony.

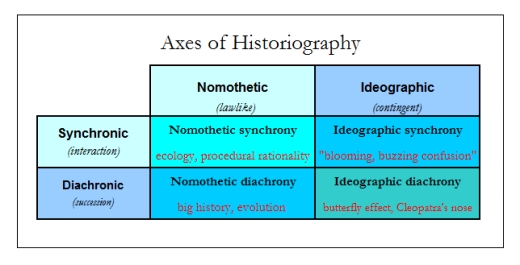

The use I have made in the present essay of concepts from historiography can be extrapolated more generally to other concepts from historiography, specifically, what I have elsewhere called the axes of historiography. If we take two distinctions common in historiography—synchronic and diachronic on the one hand, and on the other hand nomothetic and ideographic—and make these the axes of a chart, we have four permutations of historiography: nomothetic synchrony, ideographic synchrony, nomothetic diachrony, and ideographic diachrony. All of these concepts have potential for elucidating the study of the future by way of the methods of history.

The macrohistorical period that I have here identified as the longue durée of early spacefaring civilization can be given an account in terms of lawlike interactions (nomothetic synchrony), contingent interactions (ideographic synchrony), lawlike succession (nomothetic diachrony), and contingent succession (ideographic diachrony). In order to do justice to these ideas it would be necessary to given an account of Heinrich Rickert’s exposition of the nomothetic and the ideographic, but this must be a task for another time.

—————————————————————————————————————

Notes

[1] We could posit a law of history such that the greater the separation of two or more objects or events in diachronic time, the less their interaction in synchronic time. This implies, conversely, that the greater the interaction between two or more objects or events in synchronic time, the less is their separation in diachronic time. In other words, interaction is proportional to proximity. The most dramatic interactions will be seen between objects or events in close temporal proximity. I will not develop this thought further at present.

[2] It has become a commonplace to cite the buildout of the Chinese imperial navy and its voyages during the early Ming dynasty (from 1405 to 1433) under Zheng He, taking this as an instance of a seafaring capacity for expansion that was not exploited and was subsequently dismantled.

[3] The reference, “blooming, buzzing confusion” is to a passage in William James: “The baby, assailed by eyes, ears, nose, skin, and entrails at once, feels it all as one great blooming, buzzing confusion; and to the very end of life, our location of all things in one space is due to the fact that the original extents or bignesses of all the sensations which came to our notice at once, coalesced together into one and the same space.” (Principles of Psychology, Chapter XIII) I have elsewhere used this phrase to convey the sense of synchronic historiography.

[4] Of course this assertion admits of exceptions. If, for example, the Breakthrough StarShot initiative manages to successfully launch a “starchip” to a nearby star, and this occurs within the temporal window of the buildout here considered, this will be like our early automated probes of the solar system, which (over time) transformed our scientific knowledge, but which had little impact on large-scale economic and political developments as they occurred. Indeed, this kind of “exception” underscores two points already made above: A) the importance of a synchronic perspective on buildout, which takes account of minor developments in marginal fields as part of the whole ensemble of the present, and B) how the buildout of a civilization always shades over a little into the next developmental stage of a civilization (whether or not that development comes to fruition).

[5] I can imagine a reader at this point asking, “What about 3D printing?” So-called 3D printing is not the same as an industrial infrastructure. (I say “so-called” only because 3D printing is not really printing, it is automated manufacturing.) 3D printing requires the resources of an industrialized economy for its inputs, and for the construction and maintenance of the printer itself. For a complete industrialized infrastructure, there needs to be a supply chain from raw materials to finished products; 3D printing can fulfill some of the roles in this supply chain, but it cannot substitute for them all.

[6] Venture capital firms, too, are subject to winnowing over the selection pressure of what products and services prove to be robust in the market. If they are too subject to manipulation and bias, they throw their money away on debacles like Theranos and Juicero, and if this happens often enough they will exhaust their capital and be forced to cease operations.

[7] Peter Thiel, in his book Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future, emphasizes the importance of magnitude of order improvements as being especially desirable from the standpoint of venture capitalists, and therefore, also, for the successful entrepreneur, but I will point out that what Thiel says about order of magnitude improvements may be a necessary condition of a technology that will attract funding, but it is not a sufficient condition.

[8] Currency markets are a world unto themselves, because currencies are those commodities that are both bought and sold in and of themselves, as well as being the measure by which other commodities are bought and sold.

[9] There is a long-running controversy in the philosophy of science over the nature of induction. Hume is usually interpreted as having shown the ultimate shortcomings of induction, but since this is a philosophical embarrassment, it is usually only spoken of in hushed tones. Popper claimed that induction is superfluous and that science actually proceeds by deduction. Carnap defended induction. Suffice it to say that this controversy has taken on a life of its own and, if the reader is interested to follow up on this, I recommend the bibliography to the article “The Problem of Induction” in the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

[10] The Federalist Papers, no. 10, James Madison.

[11] The use of the phrase “killer app” plays into a kind of lazy diachronic extrapolation, and in so far as anyone is waiting for the “killer app” of space travel they will be disappointed. Killer apps are products with a definite lifespan, backed by investors who want to, “Get in. Get rich. Get out.” This is a good way to make money in the short term, but the economy on the whole is the sum total of overlapping products like this, and not any one individual product. Moreover, the economy also includes all the failed products that don’t make anyone rich, and the fortunes that these failed products take with them when they fail.

[12] “The Situation of History in 1950,” Fernand Braudel, in On History, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1980, p. 10. This was Braudel’s inaugural lecture at the Collège de France.

[13] Benjamin, Walter, “Paralipomena to ‘On the Concept of History’,” in Selected writings: Walter Benjamin, Volume 4, 1938-1940, edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, Harvard University Press, 2003, p. 402. Benjamin’s often cryptic “On the Concept of History” is greatly enhanced by these supplementary texts, which exhibit some of Benjamin’s thought processes while writing. Also, the Harvard edition has a lot of helpful notes. Benjamin committed suicide a few months after this was written, and I cannot help but wonder if he would have further developed this insight if he had not chosen to end his life.

[14] To understand how the Russian revolution’s vision of socialist industrialization was celebrated across all sectors of society it is instructive to read Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s “Bratsk Station,” which is an epic poem chronicling the building of a hydroelectric power station in Siberia. The human cost of socialist industrialization was high, as the absence of democratic mechanisms and press freedoms meant that abuses went unchecked, ultimately undermining the legitimacy of a state that claimed to represent the working class.

[15] I specify “macrohistorical period” because many traditionally recognized periods in the development of western civilization—the renaissance, the Reformation, the Enlightenment, romanticism, etc.—are episodic in comparison to the longue durée. Braudel might well have called these familiar periods conjunctures. Indeed, all of these named periods might be taken together as “early modern European history,” and the centuries of early modern history could well be studied in terms of the longue durée. Within the longue durée of spacefaring buildout we might similarly define periods of conjuncture, just as I have, in this essay, distinguished the earliest phase of spacefaring from 1957 to the present day.

[16] Fernand Braudel, “History and the Social Sciences: The Longue Durée,” in On History, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1980, p. 130. Machiavelli, by contrast, might be taken as a master of the history of the event, or episodic history (histoire événementielle), with his focus on fortune (Fortuna).

The Sounds of Europa

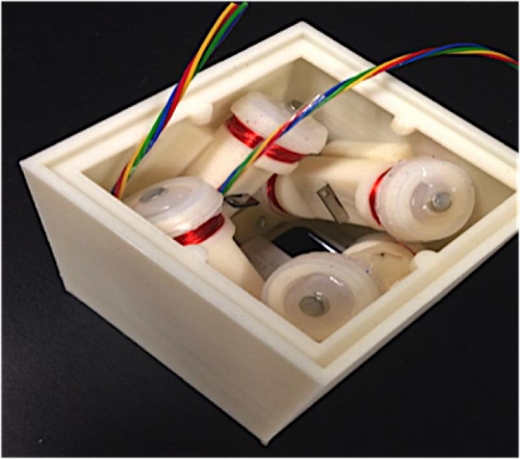

Although there are no plans at present to send a lander to Europa, we continue to work on the prospects, asking what kind of operations would be possible there. NASA is, for example, now funding a miniature seismometer no more than 10 centimeters to the side, working with the University of Arizona on a project called Seismometers for Exploring the Subsurface of Europa (SESE). Is it possible our first task on Europa’s surface will just be to listen?

The prospect is exciting because what we’d like to do is find a way to penetrate the surface ice to reach the deep saltwater ocean beneath or, barring that, any lakes that may occur within the upper regions of the ice shell. The ASU seismometer would give us considerable insights by using the movements of the ice crust to tell us how thick it is, and whether and where ocean water that rises to the surface can be sampled by future landers.

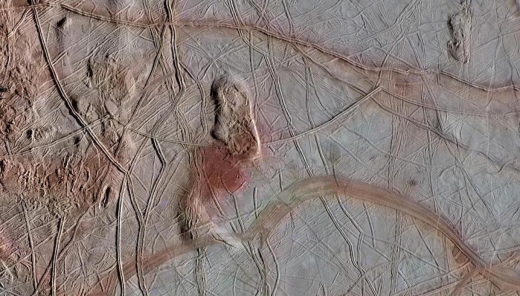

Image: Close-up views of the ice shell taken by the Galileo spacecraft show uncountable numbers of fractures cutting across each other. Reddish colors (enhanced in this view) come from minerals in ocean water leaking through the shell and being bombarded by Jupiter’s radiation. The ASU-designed seismometer would land on the shell and detect its movements. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Europa’s story is all about tides. The moon (a bit smaller than our own Moon) is constantly being tugged by the large Galilean moons Io and Ganymede, preventing its orbit from circularizing completely. In turn, that small orbital eccentricity allows Jupiter to stress the ice shell. Alyssa Rhoden is an ASU geophysicist working on the SESE project. She points out in this ASU news release that seismometers can tell us how active the ice shell is.

Acknowledging that we’re dealing with a geologically young surface — probably between 50 to 100 million years old, based on crater counts and resurfacing — Rhoden adds: “It may have undergone an epoch of activity early in that period and then shut down.” Equally plausible is the idea that even today the shell is undergoing uplifts and fracturing from below, with the opportunity for ocean water to reach the surface. Recent observations of plumes on Europa, based on Hubble data from 2012 and 2016, support the idea.

Seismometers would help us detect ongoing activity in the shell. ASU envisions a seismometer mounted on each leg of a lander — four to six seismometers in all, depending on lander design. These would be driven deep into the ground, avoiding the kind of loose surface materials that would isolate the instruments from seismic waves passing through the shell. And that calls for the kind of rugged instrument ASU is building. Able to operate at any angle, the prototype can survive landings hard enough to ensure deep penetration for each seismometer.

Edward Garnero is an ASU seismologist who points out that the instrument package will need to sample a wide range of potential vibrations, combining observations from each seismometer to pinpoint the source of seismic activity:

“We can also sort out high frequency signals from longer wavelength ones. For example, small meteorites hitting the surface not too far away would produce high frequency waves, and tides of gravitational tugs from Jupiter and Europa’s neighbor moons would make long, slow waves.”

The sound of Europa? Garnero adds:

“I think we’ll hear things that we won’t know what they are. Ice being deformed on a local scale would be high in frequency — we’d hear sharp pops and cracks. From ice shell movements on a more planetary scale, I would expect creaks and groans.”

Image: Four sensors arranged in a box measuring about 10 centimeters on a side make up the test module for the SESE project seismometer. The various sensor orientations allow the instrument to work no matter how it lands on the surface. Credit: Hongyu Yu/ASU.

The Seismometers for Exploring the Subsurface of Europa project avoids the mass-and-spring sensor concept used in conventional instruments because that design is delicate enough that it needs to be put in place without any serious jolts and must be installed in an upright position. The SESE seismometer avoids those problems and uses a micro-electromechanical system with a liquid electrolyte as its sensor, offering high sensitivity to a wide range of vibrations.

Finding pockets of water within the upper ice would offer further areas of astrobiological interest and add to the likelihood of nutrients being transported from the ocean to the surface. Thus the findings of a seismometer like this could be crucial for future lander missions. Galileo imagery has shown us long linear cracks and ridges broken by areas of disrupted terrain where surface ice has refrozen. If Europa remains active today, we can use what SESE hears on the surface to predict the best areas for future lander operations.

“We want to hear what Europa has to tell us,” adds Hongyu Yu (ASU School of Earth and Space Exploration), who heads up the project. “And that means putting a sensitive ‘ear’ on Europa’s surface.”

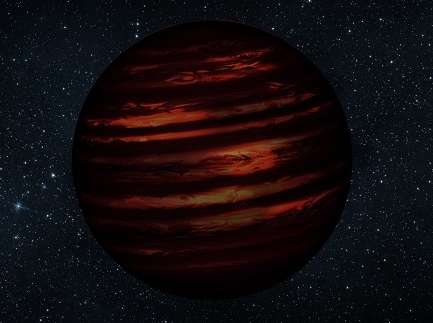

Exploring the Planet / Brown Dwarf Boundary

The boundary between brown dwarf and planet is poorly defined, although objects over about 13 Jupiter masses (and up to 75 Jupiter masses) are generally considered brown dwarfs. Brown dwarfs do not reside, like most stars, on the main sequence, being not massive enough to sustain nuclear fusion of hydrogen in their cores, although deuterium and lithium fusion is a possibility. But new work on a brown dwarf called SIMP J013656.5+093347 (mercifully shortened to SIMP0136) is giving us fresh insights into the planet/dwarf frontier.

The intriguing object is found in the constellation Pisces, the subject of previous studies that focused on its variability, which has been interpreted as a signature of weather patterns moving into and out of view during its rotation period of 2.4 hours. Now Jonathan Gagné (Carnegie Institution for Science) and an international team of researchers have put new constraints on SIMP0136, finding it to be an object of planetary mass.

Image: Lead author Jonathan Gagné. Credit: Carnegie Institution for Science.

Faint brown dwarfs and cold planetary-mass objects repay close study because as we move just below the deuterium burning mass boundary we are looking at objects much like the gas giants we can observe in exoplanetary systems. But the observations are tricky: Although these borderline objects have physical properties like temperatures, clouds, surface gravities and masses similar to gas giant planets, they also cool down with time, so that their masses cannot be deduced from their effective temperatures alone.

We also need to know about the age of the object we’re looking at, and it is here that the new work helps. Using data from the Near Infrared Spectrometer (NIRSPEC) on the Keck II instrument at Mauna Kea, Gagné and team have identified SIMP0136 as a likely member of the 200 million year old Carina-Near moving group. Moving groups are groups of similarly aged stars moving together through space, offering the possibility of dating any objects that can be associated with them. This faint brown dwarf clearly fits the bill.

Knowing not just the temperature of an object but its age as well, we can calculate its mass. SIMP0136 turns out to be just below the borderline we normally assign to the smallest brown dwarfs. The object has a mass of 12.7 Jupiter masses, plus or minus 1 Jupiter mass.

Assuming that this object is indeed a free-floating planet as opposed to a brown dwarf, it becomes part of a useful category in this mass range. Studying an exoplanetary atmosphere within a distant star system is complicated by the light of the central star, although with closely orbiting gas giants, the possibility of studying starlight filtered through their atmospheres during transits is available. But atmospheric studies of free-floating worlds are easier to conduct in detail, once we have made the key distinction between planetary status and star.

Image: An artist’s conception of SIMP J013656.5+093347, or SIMP0136 for short, which the research team determined is a planetary-like member of a 200-million-year-old group of stars called Carina-Near. Credit: NASA/JPL, slightly modified by Jonathan Gagné.

We’re also dealing with an object that is relatively close to the Sun. At a distance of just under 20 light years, it is the nearest known member of any young stellar moving group and among the 100 nearest systems to the Sun. SIMP0136 turns out to be, the authors add, “…an even more powerful benchmark than previously appreciated and will help [us] to understand weather patterns in gaseous giant atmospheres.”

Cold planetary-mass objects like this one can be found almost anywhere in the sky, since they are not in orbit around a star. That makes them hard to discover. No wonder we’ve only found about twelve objects on the brown dwarf / planet boundary, and most of these have yet to be confirmed by radial velocity measurements. We should have more soon, because this discovery is one of the early results from the BANYAN All-Sky Survey-Ultracool (BASS-Ultracool), which intends to locate similar young brown dwarfs in moving groups, aiming to explore the properties of planetary-mass objects with cold atmospheres.

The paper is Gagné et al., “SIMP J013656.5+093347 is Likely a Planetary-Mass Object in the Carina-Near Moving Group,” accepted at Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint).

Incentive Trap 2: Calculating Minimum Time to Arrival

When to launch a starship, given that improvements in technology could lead to a much faster ship passing yours enroute? As we saw yesterday, the problem has been attacked anew by René Heller (Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research), who re-examined a 2006 paper from Andrew Kennedy on the matter. Heller defines what he calls ‘the incentive trap’ this way:

The time to reach interstellar targets is potentially larger than a human lifetime, and so the question arises of whether it is currently reasonable to develop the required technology and to launch the probe. Alternatively, one could effectively save time and wait for technological improvements that enable gains in the interstellar travel speed, which could ultimately result in a later launch with an earlier arrival.

All this reminds me of a conversation I had with Greg Matloff, author of the indispensable The Starflight Handbook (Wiley, 1989) about this matter. We were at Marshall Space Flight Center in 2003 and I was compiling notes for my Centauri Dreams book. I had mentioned A. E. van Vogt’s story “Far Centaurus,” originally published in 1944, in which a crew arrives at Alpha Centauri only to find its system inhabited by humans who launched from Earth centuries later. I alluded to this story yesterday.

Calling it a ‘terrific story,’ Matloff discussed it in terms of Robert Forward’s thinking:

“Bob had a couple of concepts of technological advancement. He had a famous plot of the velocity of human beings versus time. And he said if this is true, and you launch a thousand-year ship today, in a century somebody could fly the same mission in a hundred years. Theyre going to be passed and will probably have to go through customs when they get to Alpha Centauri A-2.”

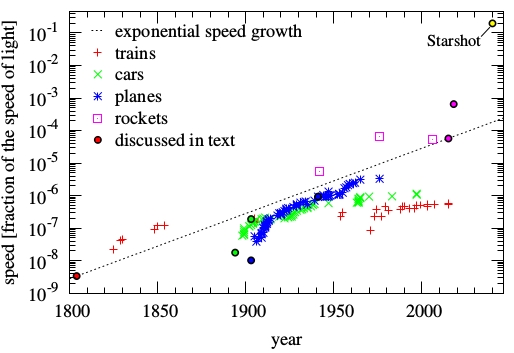

Customs! Clearly, we’d rather not be on the slow starship that is superseded by new technologies. What Heller and Kennedy before him want to do is to figure out a rational way to decide when to launch. If we make assumptions about the exponential growth in speed over time, we can address the question by adding the time we spend waiting for better technology to the time of the actual journey. We can then calculate a minimum value for this figure based on the growth rates we find in our historical data.

This is how Kennedy came up with a minimum figure of 712 years (from 2006) to reach Barnard’s Star, which is about 6 light years away. The figure would include a long period of waiting for technological improvement as well as the time of the journey itself. Kennedy used a 1.4 percent annual growth in speed in arriving at this figure but, examining 211 years of data on historical speed records, Heller finds a higher annual growth, some 4.72 percent.

From the Penydarren steam locomotive of 1804 to Voyager 1, we see a speed growth of about four orders of magnitude. Growth like this maintained for another 112 years leads to 1 percent of lightspeed.

Image: A Bussard ramjet in flight, as imagined for ESA’s Innovative Technologies from Science Fiction project. Credit: ESA/Manchu.

But how consistent should we expect the growth in speed over time to be? Heller points out that the introduction of new technologies invariably leads to jumps in speed. We are now in the early stages of conceptualizing the Breakthrough Starshot project, which could create exactly this kind of disruption in the trend. Starshot aims at reaching 20 percent of lightspeed.

Working with the exponential speed doubling law we began with, we would expect that a speed of 20 percent of c would not be achieved until the year 2191. But if Starshot achieves its goal in the anticipated time frame of several decades, its success would see us reaching interstellar speeds much faster than the trends indicate. Starshot, or a project like it, would if successful exert a transformative effect as a driver for interstellar exploration.

We know that speed doubling laws cannot go on forever as we push toward relativistic speeds (we can’t double values higher than 0.5 c). But as we move toward substantial percentages of the speed of light, we see powerful gains in speed as we increase the kinetic energy beamed to a small lightsail like Starshot’s. Thus Heller also presents a model based on the growth of kinetic energy, noting that today the Three Gorges Dam in China can reach power outputs of 22.5 GW. 100 seconds exposure to a beam this powerful would take a small sail probe to speeds of 7.1 percent of c. Further kinetic energy increases could allow relativistic speeds for at least gram-to-kilogram sized probes within a matter of decades.

Usefully, Heller’s calculations also show when we can stop worrying about wait times altogether. The minimum value for the wait plus travel time disappears for targets that we can reach earlier than a critical travel time which he calls the ‘incentive travel time.’ Considered in both relativistic and non-relativistic models, this figure (assuming a doubling of speed every 15 years) works out to be 21.6 years. In Heller’s words, “…targets that we can reach within about 22 yr of travel are not worth waiting for further speed improvements if speed doubles every 15 yr.”

Thus already short travel times mean there is little point in waiting for future speed improvements. And in terms of current thinking about Alpha Centauri missions, Heller notes that there is a critical interstellar speed above which gains in kinetic energy beamed to the probe would not result in smaller wait plus travel times. His equations result in a value of 19.6 percent of c, an interesting number given that Breakthrough Starshot’s baseline is a probe moving at 20 percent of c, for a 20-year travel time. Thus:

In terms of the optimal interstellar velocity for launch, the most nearby interstellar target α Cen will be worthy of sending a space probe as soon as about 20 % c can be achieved because future technological developments will not reduce the travel time by as much as the waiting time increases. This value is in agreement with the 20 % c proposed by Starshot for a journey to α Cen.

We can push this result into an analysis of stars beyond Alpha Centauri. Heller looks at speeds beyond which further speed improvements would not result in reduced wait times for ten of the nearest bright stars. The assumption here would be that Starshot or alternative technologies would be continuously upgraded according to historical trends. Plugging in that assumption, we wind up with speeds as high as 57 percent of lightspeed for 70 Ophiuchi at 16.6 light years.

Thus the conclusion: If something like Breakthrough Starshot’s beaming capabilities become available within 45 years — and assuming that the kinetic energy transferred to the probes it pushes could be increased at the historical rates traced here — then we can reach all ten of the nearest star systems with an interstellar probe within 100 years from today.

Just for fun let me conclude with a snippet from “Far Centaurus.” Here a ship is approaching the ‘slowboat’ that has just discovered that Alpha Centauri has been reached by humans long before. The crew has just puzzled out what happened:

I was sitting in the control chair an hour later when I saw the glint in the darkness. There was a flash of bright silver, that exploded into size. The next instant, an enormous spaceship had matched our velocity less than a mile away.

Blake and I looked at each other. “Did they say,” I said shakily, “that that ship left its hangar ten minutes ago?”

Blake nodded. ‘They can make the trip from Earth to Centauri in three hours,” he said.

I hadn’t heard that before. Something happened inside my brain. “What!” I shouted. “Why, it’s taken us five hund… ” I stopped. I sat there.

“Three hours!” I whispered. “How could we have forgotten human progress?”

The René Heller paper discussed in the last two posts is “Relativistic Generalization of the Incentive Trap of Interstellar Travel with Application to Breakthrough Starshot” (preprint).

The Incentive Trap: When to Launch a Starship

Richard Trevithick’s name may not be widely known today, but he was an important figure in the history of transportation. A mining engineer from Cornwall, Trevithick (1771-1833) built the first high pressure steam engine, and was able to put it to work on a railway known as the Penydarren because it moved along the tramway of the Penydarren Ironworks, in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales, running 14 kilometers until reaching the canal wharf at Abercynon. The inaugural trip marked the first railway journey hauled by a locomotive, and it proceeded at a blistering 4 kilometers per hour. The year was 1804.

Image: The replica Trevithick locomotive and attendant bar iron bogies at the Welsh Industrial & Maritime Museum in 1983. Credit: National Museum of Wales.

Consider, as René Heller (Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research) does in a new paper, how Trevithick’s accomplishment serves as a kind of bookend for 211 years of historical data on the growth in speed in human-made vehicles from the Penydarren to Voyager 1. The world’s first production car was the Benz Velocipede (1894), whose top speed of 19 kilometers per hour far surpassed the Trevithick railway, but was put to shame by a Stanley Steamer racing car that reached a then incredible 204 kilometers per hour in 1903.

I mused about the nature of speed in a 2013 post called The Velocity of Thought, and Heller’s new paper has me doing it again, though in entirely different directions. A few more waypoints and I’ll explain what I mean. When the Wright Brothers took to the air in 1903, their Wright Flyer first flew at about 11 kilometers per hour, and we began to see how quickly aviation records could be superseded. A Sopwith Camel of World War I vintage could reach 181 kilometers per hour. By 1944, German test pilot Heini Dittmar was able to take a ME-163 rocket plane to 1130 km/h, a number that wouldn’t be reached again for almost ten years.

Image: Typical appearance of a Me-163 Komet after landing, waiting for the airfield’s Scheuch-Schlepper tractor and lifting trailer to tow it back for reattachment of its “dolly” maingear. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

When we get into space, we can note Voyager 1’s 17 kilometers per second as it leaves the Solar System. The Helios solar probes launched in 1974 and 1976 set the current record at 70.22 km/s. And looking forward, the Solar Probe Plus mission is to perform a close flyby of the Sun, reaching a top heliocentric speed of 195 kilometers per second, which works out to 6.5 × 10 ?4 c. If Breakthrough Starshot realizes its goal, an interstellar lightsail may one day head for Proxima Centauri at fully 20 percent of the speed of light.

Part of what occupies René Heller in his new paper is the exponential growth law we can construct between the 1804 Penydarren locomotive and the 17 kilometers per second of Voyager 1 in 2015. From wind- to steam-driven ships and into the realm of automobiles, then aircraft and, finally, rockets, we can extrapolate speeds that may take us into interstellar probe territory some time in this century or the next. Given that an interstellar mission may take longer than the average human lifetime, we thus need to ask a key question. When do we launch?

Image: Figure 1 from the Heller paper, showing historical speed records. From the paper: “All these values are symbolized with black-rimmed circles in Figure 1, with additional top speed measurements of trains, cars, planes, and rockets shown with different symbols (see legend). The dashed black line illustrates an exponential growth law connecting the 1 m s ?1 speed of the “Penydarren” steam locomotive in 1804 with the 5.7 × 10 ?5 c Solar System escape speed of Voyager 1 in 2015. Credit: René Heller.

For the problem, a classic in science fiction, is to work out the most efficient timing. If we launch a starship at a particular level in our technology, will it not be caught by a faster ship launched at a much later date? Given sufficient technological improvements, a later launch (incorporating the necessary ‘wait time’) could result in an earlier arrival.

Those who have read A. E. van Vogt’s story “Far Centaurus” will recall precisely that scenario, when an Alpha Centauri mission reaches destination only to find it populated by humans who arrived by faster means. It’s a theme that shows up in Heinlein’s Time for the Stars and many other places.

Heller calls this problem ‘the incentive trap.’ And he refers back to Andrew Kennedy’s 2006 paper, which looked at the problem with the assumption of an exponential growth of the interstellar travel speed. Kennedy was assuming a 1.4 % average growth rate, under which a minimum time to reach Barnard’s Star could be calculated: some 712 years from 2006.

What that means is this: There is a total time that includes the waiting time (waiting for improved technology) and the actual travel time, and we can calculate a minimum value for this total time by using our assumption about the exponential growth of the interstellar travel speed. Calculating the minimum value shows us when we can launch without fear of being overtaken by a faster future probe, in hopes of avoiding that “Far Centaurus” outcome.

But was Kennedy right? Heller’s own take on the incentive trap takes into account the possibility that Breakthrough Starshot may achieve a velocity of 20 percent of lightspeed within several decades, an outcome that would, in Heller’s words, “…fundamentally change both the assumptions and the implications of the incentive trap because the speed doubling and the compounded annual speed growth laws would collapse as v approaches c.” And whatever happens with Breakthrough Starshot, the speed growth of human-made vehicles turns out to be much faster than previously believed.

Intriguing results flow out of Heller’s re-examination of what Kennedy had called the ‘wait equation,’ and tomorrow I want to go deeper into the paper to explain how the scientist uses exponential growth law models to show us a velocity which, once we have attained it, will no longer be subject to the incentive trap of faster, later technologies. The results are surprising, particularly if Breakthrough Starshot achieves its goal in the planned 30 years. The implications for our reaching well beyond Alpha Centauri, as we’ll see, are striking.

The Heller paper is “Relativistic Generalization of the Incentive Trap of Interstellar Travel with Application to Breakthrough Starshot” (preprint). The Kennedy paper is “Interstellar Travel: The Wait Calculation and the Incentive Trap of Progress,” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society Vol. 59, No. 7 (July, 2006), pp. 239-247.

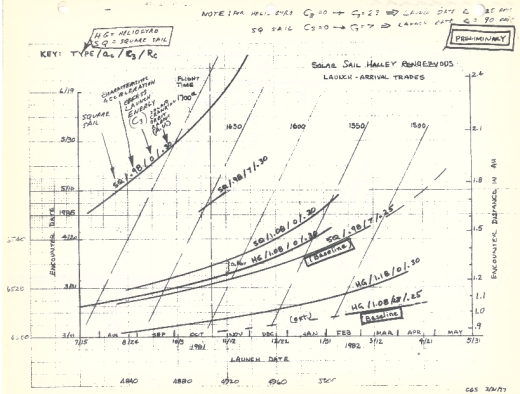

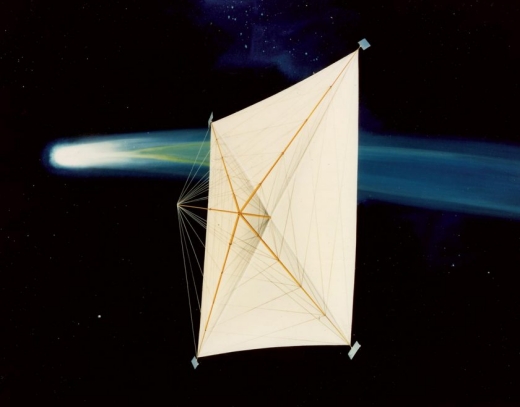

Remembering the Sail Mission to Halley’s Comet

Some years back I had the pleasure of asking Lou Friedman about the solar sail he, Bruce Murray and Carl Sagan championed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the 1970s. NASA had hopes of reaching Halley’s Comet with a rendezvous mission in 1986. Halley’s closest approach that year would be 0.42 AU, but the comet was on the opposite side of the Sun from the Earth, making ground viewing less than impressive. Although the JPL mission did not fly, the Soviet Vega 1 and Vega 2 conducted flybys and the European Space Agency’s Giotto probe, as well as the Japanese Suisei and Sakigake, made up an investigative ‘armada.’

But the abortive NASA concept has always stuck in my mind because it seemed so far ahead of its time. Friedman acknowledged as much in our short conversation, saying that while the ideas were sound, the solar sail technology wasn’t ready for the ambitious uses planned for it. Friedman, of course, would go on to become a founder of The Planetary Society and its long-time executive director, championing sail concepts like Cosmos 1 and the LightSail 1 and LightSail 2 spacecraft. He’s also the author of one of the earliest books on this form of propulsion, Starsailing: Solar Sails and Interstellar Travel (Wiley, 1988).

Image: This artist’s concept shows an 850-by-850-meter wide solar sail spacecraft approaching Halley’s Comet. Credit: JPL-Caltech.

Starsailing is a slim but compelling book that should be on your shelf if you’re interested in these concepts and their history. Although out of print, it’s readily available through Amazon or eBay sellers. Meanwhile, The Planetary Society’s Jason Davis has made a cache of documents from engineer Carl Berglund available that cover many details of the mission. The self-deprecating Berglund, who refers to himself as a only a ‘cog engineer’ at JPL, joined the project at about the same time that Carl Sagan displayed a model of a solar sail on The Tonight Show, and while he only spent several months working on the sail, his JPL documents remind us just how ambitious the JPL concept had become.

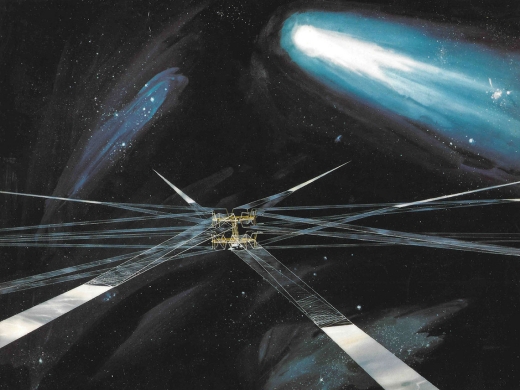

Not one but two designs were under consideration, the first a square sail 850 meters to the side. Bear in mind that JAXA’s IKAROS sail, the largest we’ve yet deployed in space, runs 14 meters to the side. A second design was a heliogyro, a device with long blades aptly described by Davis as looking like “two ceiling fans stacked on top of each other.” There would be 12 sail blades in all, 6 per level, and here the dimensions really are staggering. Each blade was to be 8 meters wide and 6.2 kilometers long, making for 0.6 square kilometers of sail material in a spinning blade configuration that would complete a rotation every 200 seconds.

Let’s take a closer look at that heliogyro, as it’s a design we’ve yet to see in space. In a summary document written in early 1977, Friedman describes the concept this way:

The Heliogyro presents a large reflective area to create the Solar Sail by the use of very long, thin blades, much like helicopter blades, which are used both to reflect the solar pressure and to control the vehicle. The basic concept is to spin the vehicle and to use the centrifugal force to support and stiffen the blade, and to keep it flat relative to the Sun. The spin of the vehicle also aids in the deployment of the Heliogyro blades. In addition, the blades can be pitch controlled, as with a helicopter, in order to provide attitude control and to turn the vehicle so that the reflective plane can have different orientations with respect to the Sun. Thus, the vehicle can either fly in toward the Sun or fly out into the Solar System.

Image: Halley’s Comet Heliogyro Design. Credit: JPL-Caltech, 1976).

The document depicts a deployment in which the blades unroll from their storage rollers with the help of spin thrusters that are jettisoned after the first 100 meters. After this, solar torque on the blades continues to spin up the vehicle and, over the course of a two-week period, each of the blades unfurls to its full six-kilometer length. Friedman sees the major advantage of the heliogyro as being the support provided by its centrifugal spin, which eliminates the need for a stiffening structure and provides for higher performance than a square sail. The major uncertainty: The dynamics of a 6 kilometer long spinning blade in deep space.

As to sail materials, Friedman describes blades “made out of .1 mil plastic material, with a surface density of less than 4 grams per square meter,” with surface coatings on the back to allow the sail to work at high temperatures close to the Sun. An internal newsletter from Friedman on April 13 of 1977 looks at materials requirements and notes three film candidates: Kapton, Ciba-Geigy polyimid and PBI conformal coated with parylene. These films were specified in the 1.5 to 2.5 µm range in thickness. By way of comparison, the later IKAROS sail was made of a 7.5-micrometer thick sheet of polyimide with thin-film solar cells.

Whichever sail design got the nod, the plan was to launch from the Space Shuttle followed by an inward spiral toward the Sun to about 0.25 AU, after which the sail would leave the ecliptic as it reached speeds in the range of 55 kilometers per second, eventually matching the trajectory of Halley’s Comet in 1986. The sail would be jettisoned at the comet, allowing the craft to use maneuvering thrusters for its operations there, which were to include a landing on the comet itself at the end of the mission.

The heliogyro option ended up winning the competition over the square sail, but sail concepts themselves lost out to solar electrical power, an ion propulsion technology like that used in the Dawn spacecraft. But funding problems and a slower than expected Space Shuttle mission schedule brought all thoughts of a Halley’s Comet mission from NASA to an untimely end.

Friedman writes in Starsailing that in the 1977 to 1978 period, the JPL team produced its design study for the mission with the help of half a dozen industrial contractors and support from the NASA Ames and Langley research centers. It was solid work that showed how viable solar sailing could be as a method of propulsion. He also describes the outcome of the Halley’s mission design:

Despite the confidence of the technical team and the completion of a valid preliminary design, however, the NASA management was conservative. They felt the design and implementation could not be accomplished in time for a 1981 launch to Halley’s Comet. NASA also thought that the technology for solar sailing was not sufficiently ‘mature’ to be implemented on a near-term space project. Indeed, the Halley mission requirements were severe — and even our willingness to incur great risk for great gain was insufficient to overcome management’s skepticism. And as it turned out, the conservatives were right, we could not have done it. It was a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But what splendid work fleshing out solar sail concepts that we continue to explore and find viable. As mentioned above, The Planetary Society’s Lightsail 2 carries the idea forward, and may become the second solar sail to demonstrate controlled flight in space. JAXA, meanwhile, has plans for an IKAROS follow-on mission to study the Jupiter Trojans.

All of that helps us keep the documents Jason Davis has collected online in perspective, a valuable look at work that has contributed to our understanding of a key propulsion concept. Looking through these documents reminds me of days I spent in 2003 going through the Robert Forward notebooks stored at the University of Alabama at Huntsville. That sense of history in the making — or in this case, history that might have been — is palpable as we consider who developed these documents and handled them at the key JPL meetings.

Image: Dig into documents like this online to see a mission design emerging. Credit: Carl Berglund / The Planetary Society / Louis Friedman.

Friedman includes in one of the newsletters a March 14, 1977 article in Science covering the JPL sail work. It reminds us how exotic sail ideas were at the time. Quoting from it:

[The sail] might also effectively open up the rest of the Solar System to manned spaceflights that cannot be considered now because of tremendous costs. JPL’s Louis Friedman thinks that a flotilla of sunjammers could embark on a manned Mars mission by the end of the century, and foresees a day when fleets of huge kites shuttle through space — as the East Indiamen plied the oceans three centuries ago — making regular stops at Mercury, Venus, Mars or the asteroids.

Exotic ideas indeed, but slowly, surely, beginning to take shape. For more background, see Davis’ Sailing to the World’s Most Famous Comet.