Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Fast Radio Bursts: Signature of Distant Technology?

We have a lot to learn about Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs), a reminder that the first of these, the so-called Lorimer Burst (FRB 010724) was detected only a decade ago. Since then we’ve found 16 others, all thought to be at cosmological distances. The 2015 detection of FRB 150418, at first thought to have left an afterglow, has now been traced to an active galactic nucleus powered by a supermassive black hole. FRB 121102 appears to be a rare case of a repeating FRB (about which more a bit later). The distances involved and the brightness of the FRBs have led to source hypotheses ranging from gamma ray bursts to massive neutron stars.

But as Avi Loeb (Harvard University) speculates in a new paper slated to appear in Astrophysical Journal Letters, we could conceivably be dealing with an engineering phenomenon rather than a natural one. What Loeb and Manasvi Lingam, a Harvard postdoctoral fellow at Harvard’s School of Engineering, discuss is whether FRBs could be interpreted as artificial beams set up as an infrastructure for pushing lightsails.

Analyzing the distance of the beam sources through their dispersion measures — the delay of radio frequencies as they sweep through charged particles between the Earth and the source — Loeb and Lingam go on to look at the spectra of FRBs and find them consistent with an artificial origin. Indeed, FRBs can be analyzed as the result of energetic natural processes, but we can equally well work out their parameters in terms of engineering requirements.

Image: Harvard’s Avi Loeb. Credit: Kris Snibbe (Harvard Staff Photographer).

If an extraterrestrial civilization were using the energy of a star to power these beams, and if water were being used as a coolant, such beamers, though enormous, would not violate known physics. The paper extracts a minimum aperture diameter to maintain the operation, finding it to be roughly twice the diameter of the Earth, meaning that the beamer would be an object on the order of a planet, a large ‘super-Earth’ or even a ‘mini-Neptune.’ And in keeping with the speculative nature of the inquiry, the authors point out that we can also consider beam emitters along the lines of the Stapledon-Dyson spheres that have been postulated to use stellar system materials to build artifacts surrounding and enveloping the host star.

(Let me digress to note approvingly the authors’ use of ‘Stapledon-Dyson spheres’ in place of the more common ‘Dyson spheres.’ I heartily approve of this tribute to the great philosopher and science fiction writer Olaf Stapledon, who developed the idea in works like Star Maker (1937), and think I will start using the term on Centauri Dreams).

The power involved in such a beamer could push a payload of a million tons, and the paper speculates that if a beam were indeed being used to power a spaceship, it would have to be a large one, perhaps the kind of ‘worldship’ imagined in science fiction, though not one as large as some of the worldships that have been discussed in the interstellar literature. As to what we would see of this operation on Earth, the motion of the beamer relative to the receding sail would be changing relative to the observer, which means we would detect no more than a brief flash, although powering a lightsail would require the transmitter to focus its beam continuously.

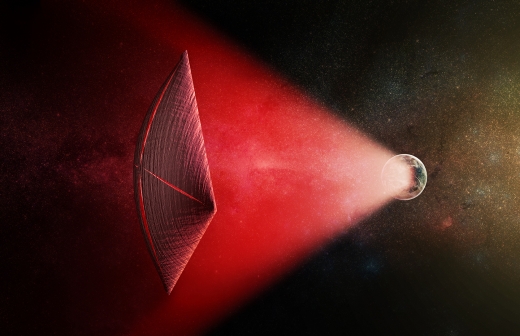

Image: An artist’s illustration of a light-sail powered by a radio beam (red) generated on the surface of a planet. The leakage from such beams as they sweep across the sky would appear as Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs), similar to the new population of sources that was discovered recently at cosmological distances. M. Weiss/CfA.

These are fascinating speculations, but what can we do to delve further into the origin of FRBs? The paper offers multiple ways into the problem:

It should be possible to distinguish between FRBs of natural and artificial (light sail) origin based on the expected shape of the pulse, as the beam sweeps by to power the light sail (Guillochon & Loeb 2015). More specifically, the sail would cast a moving shadow on the observed beam, thereby leading to a diffraction pattern and multiple peaks in the light curve based on the sail geometry (Manchester & Loeb 2016). A series of short symmetric bursts would be observed as the beam’s path intersects with the observer’s line of sight (Guillochon & Loeb 2015). Hence, looking for similar signatures in the signal could help determine whether FRBs are powered by extragalactic civilizations (although the use of a broad range of frequencies might smear these signals).

Here, then, is a target for Breakthrough Listen or other SETI initiatives, which Loeb and Lingam advocate should direct their attention toward the repeating FRB 121102, the only source known to repeat. Continuing study of this source is reasonable because we would expect astrophysical explosions of the kind advanced by some theorists to be single events, while artificial sources like lightsail beamers or beacons can repeat in the course of their normal operations.

Another interesting thought: Other models of FRBs that assume natural phenomena like gamma-ray bursts would have an FRB occurrence rate determined by the formation rate of the massive stars that produce the bursts. If, on the other hand, FRBs really are artificial and have a planetary origin, then their rate would be set by the number of planets with advanced civilizations (this draws on an interesting discussion in the paper on the upper bound of extraterrestrial civilizations — fewer than 104 FRB-producing civilizations in a galaxy like our own). Complicating this, however, is the issue of whether all FRBs have the same origin — perhaps we should focus only on repeating FRBs as possibly artificial.

For that matter, as Loeb and Lingam point out, a given civilization could set up more than one beamer, especially if it had reached a state as advanced as Kardashev II or III. As we continue investigating FRBs, it’s worthwhile remembering that 104 FRBs are now thought to occur in our sky each day. Working out detection rates for galaxies within 100 Gpc3, the authors calculate that each galaxy has a probability of 10-5 FRBs per day. We might expect one from within our own galaxy every 300 years or so, a spectacular event if it occurred anywhere within 20 parsecs, and one that could “…reveal everything that can be known about the true origin of FRBs, and thereby settle this FRB origin debate once and for all.”

It’s a fascinating discussion, and one that makes me wonder whether other signals in our astronomical data at different wavelengths might be similarly interpreted. As to the nature of such investigations, Avi Loeb makes this statement in a CfA news release:

“Science isn’t a matter of belief, it’s a matter of evidence. Deciding what’s likely ahead of time limits the possibilities. It’s worth putting ideas out there and letting the data be the judge.”

A sound reminder indeed of how to proceed in such speculative realms. The paper is Loeb and Lingam, “Fast Radio Bursts from Extragalactic Light Sails,” accepted for publication at The Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint).

HD 219134: A Nearby System with Multiple Transits

While we’ve all had our eyes fixed on TRAPPIST-1 (amid the still lingering excitement of the discovery of Proxima Centauri b), news about another stellar neighbor has caused only a faint stir. But what’s happening around HD 219134 (Gliese 892) is noteworthy, and it’s interesting to see that Michaël Gillon (University of Liège – Belgium) has had a hand in it. Gillon, after all, led the work on TRAPPIST-1’s two waves of exoplanet discoveries, culminating in the startling assemblage of seven Earth-sized worlds around the dim ultracool dwarf star.

HD 219134 is an orange K-class star (K3V) in the constellation Cassiopeia, and only about half the distance, at 21.25 light years, as TRAPPIST-1 (about 40 light years out). It was known before the recent Gillon et al. paper in Nature Astronomy that we had a super-Earth, HD 219134 b, in orbit here, which was soon joined by two more super-Earths, a gas giant and, a few months later, another two planets, making for a total of six.

This system characterization was radial velocity work using the HIRES Spectrograph at the Keck I telescope which you can track in A Six-Planet System Orbiting HD 219134 — Steven Vogt was lead author on that paper. I notice that Greg Laughlin, also at UC-Santa Cruz and a co-author on the Vogt paper, has singled out the latest work by Gillon and team on his systemic site. That’s because Gillon adds to the one already known transiting world (HD 219134 b) another transiting planet (HD 219134 c), which gives us the closest transiting exoplanet to Earth yet found.

Image: Exoplanet hunter Michaël Gillon (University of Liège, Belgium).

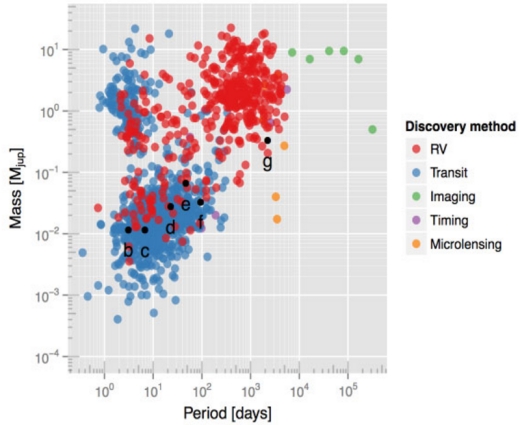

Both transits are Spitzer detections, and both planets have mass and radius estimates that make a rocky composition possible (4.74 ± 0.19?M? and 1.602 ± 0.055?R? for HD 219134 b, and 4.36 ± 0.22?M? and 1.511 ± 0.047?R? for HD 219134 c). Laughlin adds that this system “…very cleanly typifies the most common class of systems detected by the Kepler Mission — multiple-transiting collections of super-Earth sized worlds with orbital periods ranging from days to weeks. Upscaled versions, that is, of the Jovian planet-satellite members of our own solar system.”

Image: From the systemic site, the HD 219134 system plotted on a mass-period diagram of exoplanets found through the various methods of detection. Credit: Greg Laughlin.

We can expect to hear a good deal more about HD 219134 in upcoming space-based observations. Unfortunately, the K-class star is too bright for some, though not all, James Webb Space Telescope instruments. JWST may be able to detect atmospheric signatures for both transiting planets if they have extended atmospheres dominated by hydrogen. More compact atmospheres dominated by H2O or CO2 would demand precisions out of reach for JWST because of stellar brightness. The paper adds: “…the precisions are limited not by the photon noise but by the instrumental systematics.”

However, we may not be done with transits in this system. The detection of the HD 219134 c transit increases the probability that planets d and f also transit. From the paper:

Using the formalism of previous work, we compute posterior transit probabilities of 13.1% and 8.1% for planets f and d, respectively, significantly greater than their prior transit probabilities of 2.5 and 1.5%… A transit detection for one or both of these planets would increase further the importance of the system for comparative exoplanetology, and a search for their transits is thus highly desirable. Although such a transit search is probably out of reach of ground-based telescopes, it could be performed again by Spitzer, whose operations have been extended to end-2018, or by the space missions TESS [Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite] and CHEOPS [CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite], which are both due to launch in 2018.

Nearby transiting planets around a small star make HD 219134 a target we’ll be investigating for a long time to come. We can begin to put constraints on possible atmospheres for the two inner worlds in this system, and also tighten up our figures for planetary mass and radius while gaining valuable insights into the formation of super-Earths. You can see how the high-priority target catalog is growing for future observations, and we can expect our space-based assets to continue to add to it as TESS and CHEOPS come online.

The paper is Gillon et al., “Two massive rocky planets transiting a K-dwarf 6.5?parsecs away,” published online by Nature Astronomy 2 March 2017 (full text).

Kepler Data on TRAPPIST-1 Coming Online

K2 Campaign 12 is an observational window that comes at the right time. Operating as the K2 mission, the Kepler spacecraft collected data from December 15, 2016 to March 4 of this year on the TRAPPIST-1 system. With seven planets, at least six of them likely to be rocky worlds, TRAPPIST-1 is suddenly high on everyone’s target list for future observation. The new Kepler data are a key part of this, as Geert Barentsen, K2 research scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, California, explains:

“Scientists and enthusiasts around the world are invested in learning everything they can about these Earth-size worlds. Providing the K2 raw data as quickly as possible was a priority to give investigators an early look so they could best define their follow-up research plans. We’re thrilled that this will also allow the public to witness the process of discovery.”

The raw cadence data — ‘cadence’ refers to the time between observations of the same target — are available from the archive at MAST. Note that these are raw data files, absent any vetting or processing. Data that have been put through this process will be available some time in June. On the NASA Kepler & K2 site, Barentsen described the use of the data this way:

While we recommend that scientists only use the pipeline-processed data products in journal papers, we do encourage our community to share their understanding of the raw data with the public by blogging or tweeting tutorials and analyses. This public TRAPPIST-1 data set offers a unique opportunity to let a wider audience witness the process [of] scientific discovery.

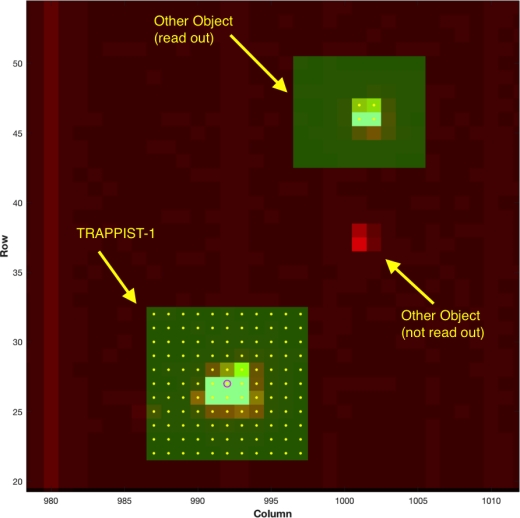

Image: Simulated image of TRAPPIST-1’s location on the detector, from the “Create Optimal Aperture” component of the Photometric Analysis module. The 11×11-pixel aperture of K2 ID 200164267 is represented by the yellow dots. The output module for TRAPPIST-1 is 19.4, its channel is 68, and it’s located approximately at pixel row 27, column 992. Credit: MAST/STScI.

Meanwhile, the raw, uncalibrated data are intended as an aid to astronomers as they prepare proposals due this month for further investigations of TRAPPIST-1 by telescopes on Earth. Needless to say, the data gathered here, once refined and fully examined, will also factor into observations of the TRAPPIST-1 planets by the James Webb Space Telescope.

K2 Campaign 12 offers 74 days of monitoring, the longest, nearly continuous set of observations of the star yet, and as this NASA news release explains, the data give us the chance to refine earlier measurements of the TRAPPIST-1 planets, refine the orbit and mass of the seventh planet (TRAPPIST-1h), and delve into the magnetic activity of the host star.

The preparation for this observing run began in May of 2016, when the discovery of the first three planets in the system was announced. The Kepler spacecraft’s operating system was then tweaked to make needed pointing adjustments for Campaign 12. A good bit of serendipity went into the observations, for the original coordinates for Campaign 12 were set in October of 2015 before the TRAPPIST-1 planets were known. Had the exoplanet discovery not occurred when it did, Campaign 12 might have missed the system entirely.

“We were lucky that the K2 mission was able to observe TRAPPIST-1. The observing field for Campaign 12 was set when the discovery of the first planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1 was announced, and the science community had already submitted proposals for specific targets of interest in that field,” said Michael Haas, science office director for the Kepler and K2 missions at Ames. “The unexpected opportunity to further study the TRAPPIST-1 system was quickly recognized and the agility of the K2 team and science community prevailed once again.”

Another indication of the importance of the TRAPPIST-1 planets, and the likelihood that atmospheres here will be among the first investigated as we begin the search for biomarkers.

Biofluorescence: A Potential Biosignature for M-Dwarf Planets

The seven planets circling the star TRAPPIST-1 have been lionized in the media, and understandably so, given that more than one have the potential for habitability. But of course M-dwarfs call up the inevitable problems associated with such tiny stars. Habitable planets must orbit close to the star, with the probability of tidal lock and subsequent climatic issues. Moreover, the flare activity particularly in young M-dwarfs gives cause for concern.

It’s the latter issue that Jack T. O’Malley-James and Lisa Kaltenegger (both at Cornell, where Kaltenegger is director of the Carl Sagan Institute) have explored in a new paper to be published in The Astrophysical Journal. As the paper explains, the question of habitability becomes troubling when we realize how frequently an M-dwarf can flare. Proxima Centauri, an M5 star, undergoes intense flares every 10 to 30 hours, with effects on the planet in its habitable zone that are still unknown. Can a planet with high doses of ultraviolet radiation remain habitable under such bombardment?

We probe such questions with particular urgency because 75 percent of the stars in the neighborhood of the Sun are M-dwarfs, and we’re about to send the TESS mission (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) into space to look for habitable zone planets around nearby stars. TESS will be able to do this for late M and early K stars, and as Kaltenegger notes, the mission is expected to uncover hundreds of planets between 1.25 and 2 Earth radii in size, and tens of Earth-sized planets, some of them likely to be in the habitable zone.

Image: Artist’s impression of the Alpha Centauri stellar system as viewed from the surface of the habitable-zone planet Proxima b. Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

TESS findings will be handed off to future ground and space-based missions for detailed study, making it likely that the first habitable zone planet that we can characterize will orbit a nearby M star. Recent studies have looked at the biological effects of radiation for atmospheres corresponding to different times in the evolution of the Earth, finding that such a planet orbiting an inactive M-dwarf would receive a lower ultraviolet flux than Earth.

But active M-dwarfs are another story. Planets orbiting such a star would receive bursts of UV in their tight, habitable zone orbits, increasing the surface UV flux by as much as two orders of magnitude for up to several hours. Add in the fact that M stars remain active for longer periods than G-class stars like the Sun, and the scenario looks dicey for life indeed. Consider the atmospheric effects, as noted in the paper:

The close proximity of planets in the HZ of cool stars can cause the planet’s magnetic field to be compressed by stellar magnetic pressure, reducing the planet’s ability to resist atmospheric erosion by the stellar wind. X-ray and EUV flare activity can occur up to 10-15 times per day, and typically 2-10 times, for M dwarfs (Cuntz & Guinan, 2016), which increases atmospheric erosion on close-in planets. This results in higher fluxes of UV radiation reaching the planet’s surface (Lammer et al. 2007; See et al., 2014) and, potentially, a less dense atmosphere.

We also have to keep in mind that in such close orbits, the effect of the star’s stellar wind would be orders of magnitude stronger in the habitable zone than what Earth experiences. The result: Erosion of any protective ozone shield and potential loss of at least some of the atmosphere. Biological molecules under such conditions can undergo mutation. We’re fortunate that on our planet, the ozone layer blocks the most damaging UV wavelengths. For life to flourish, some way of protecting it from this radiation is thus a prerequisite.

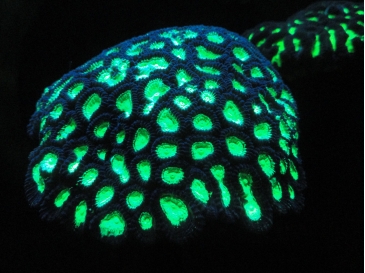

Going underwater is one solution, or burrowing deep into the ground, a strategy that could prove life-saving but also make detection by remote instruments extremely difficult. But there is one adaptation that would be detectable: photoprotective biofluorescence. In this process, protective proteins absorb harmful wavelengths and re-emit them at longer, safer wavelengths. Some species of coral are believed to use this mechanism to protect symbiotic algae needed for energy, with fluorescent proteins absorbing blue and UV photons and re-emitting them at longer wavelengths.

Image: This is Figure 1 from the paper, showing an example of coral fluorescence. Coral fluorescent proteins absorb near-UV and blue light and reemit it at longer wavelengths (see e.g. Mazel & Fuchs 2003). Image made available under Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Biofluorescence occurs when specialized fluorescent molecules are excited by high-energy light, causing them to absorb part of that energy and release the rest at lower-energy wavelengths. Such biofluorescent light can only be seen when the organism is being illuminated, which could be the key to their detection on other worlds. From the paper:

Photoprotective biofluorescence (the “up-shifting” of UV light to longer, safer wavelengths, via absorption by fluorescent proteins), a proposed UV protection mechanism of some coral species, would increase the detectability of biota, both in a spectrum, as well as in a color-color diagram. Such biofluorescence could be observable as a “temporal biosignature” for planets around stars with changing UV environments, like active flaring M stars, in both their spectra as well as their color.

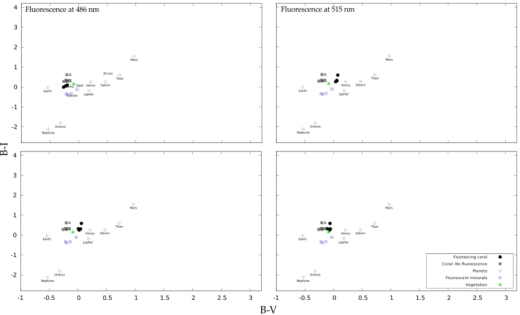

The color-color diagram referred to above is frequently used in the study of star-forming regions, and as a way of comparing the apparent magnitudes of stars. Here one observes the magnitude of an object successively through two different filters — the difference in brightness between two bands at certain wavelengths is what is referred to as ‘color.’ One brightness range is plotted on the horizontal axis, while another range is plotted on the vertical axis.

Image (click to enlarge): A color-color diagram. This is Figure 10 from the paper. Caption: Color-color diagrams of planet models with an atmosphere and 50% cloud cover, and a surface that is completely covered by biofluorescent corals, fluorescent minerals, or vegetation compared to the colors of planets in our own Solar System, before (grey – labelled A, B, C, D) and during fluorescence at each of the four common emission wavelengths. Credit: Jack O’Malley-James / Lisa Kaltenegger.

The authors argue that color-color diagrams can distinguish biological sources of fluorescence from abiotic ones, as the change in color that biofluorescence produces differs from all other forms of the phenomenon:

Using a standard astronomy tool to characterize stellar objects, a color-color diagram, one can distinguish planets with and without biofluorescent biosignatures. The change in color caused by biofluorescence differs, in position and magnitude, from that caused by abiotic fluorescence, distinguishing both.

The authors point out that Proxima b will be a prime target to search for biofluorescence with the upcoming European Extremely Large Telescope. But TESS should give us a number of useful targets as we examine stars during flare periods looking for a biofluorescent biosphere. In other words, it may be that in the case of a planet orbiting an active M-dwarf, it’s precisely the high UV flux that will allow us to detect a biosphere that would otherwise be hidden.

The paper is O’Malley-James and Kaltenegger, “Biofluorescent Worlds: Biological fluorescence as a temporal biosignature for flare stars worlds,” to be published in The Astrophysical Journal (preprint). A second paper from Lisa Kaltenegger, “UV Surface Habitability of the TRAPPIST-1 System,” is now under review at Monthly Notices of the Royal Society. More on that one when I have a copy to work with.

Ceres: Close Look at Occator Crater

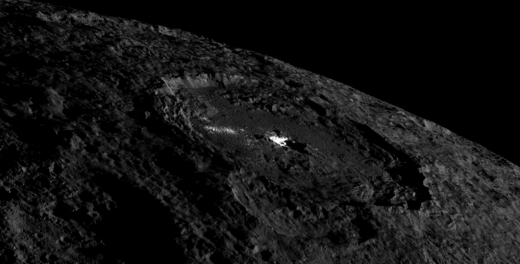

We’ve looked recently at the possibility of cryovolcanism on Ceres with regard to the unusual feature called Ahuna Mons (see Ice Volcanoes on Ceres?). Now we have further evidence that outbursts of brine from beneath the surface have been occurring over long periods of time, and that some of these eruptions have been recent. The work comes out of analysis of data from the Dawn mission by scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS), and moves the debate to the unusual crater called Occator.

Image: This view of the whole Occator crater shows the brightly colored pit in its center and the cryovolcanic dome. The jagged mountains on the edge of the pit throw their shadows on parts of the pit. This image was taken from a distance of 1478 kilometers above the surface and has a resolution of 158 meters per pixel. NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA.

Dawn’s Low Altitude Mapping Orbit (December 2015 to September 2016) took the spacecraft to within 375 kilometers of the surface, allowing highly resolved images of Ceres’ surface to be obtained. The geological structures on display within Occator, tracked by the Dawn Framing Cameras and its infrared spectrometer, include smaller, younger craters along with fractures and avalanches, all presenting us with a look into the crater’s evolution.

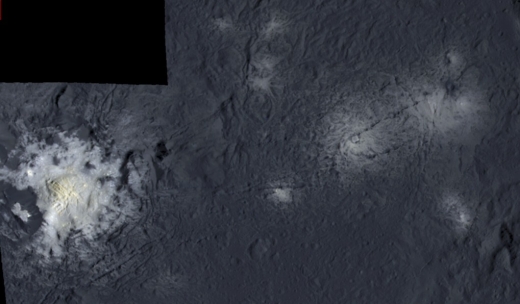

The bright dome in Occator crater’s central pit, now known as Cerealia Facula, is one of Ceres’ most intriguing features. Infrared data have shown it to be rich in carbonates. Beyond the pit itself, we also find other bright areas called Vinalia Faculae, considerably paler and evidently thinner, though likewise containing carbonates along with dark surrounding material. The MPS researchers, led by Framing Camera lead investigator Andreas Nathues, have evaluated images of Occator from various distances and different angles of view.

It took more than a single impact to produce what we see in Occator crater, though that impact was likely the trigger for subsequent cryovolcanism. As explained by Nathues:

“The age and appearance of the material surrounding the bright dome indicate that Cerealia Facula was formed by a recurring, eruptive process, which also hurled material into more outward regions of the central pit. A single eruptive event is rather unlikely.”

Image: False color mosaic showing parts of Occator crater. The images were taken from a distance of 375 kilometers. The left side of the mosaic shows the central pit containing the brightest material on Ceres. It measures 11 kilometers in diameter and is partly surrounded by jagged mountains. In the middle of the pit a dome towers 400 meters high covered by fractures. It has a diameter of three kilometers. The right side of the mosaic shows further, less bright spots in Occator crater. NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA.

What’s especially interesting here is the age issue, for this is the first time scientists have determined the age of the bright material. As this MPS news release explains, Nathues and team believe the central pit in Occator, which contains a jagged ridge, is all that is left of a former central mountain that would have formed as a result of the impact that created the crater about 34 million years ago. The age estimate comes from studying smaller craters formed from later impacts, and the Dawn images are so highly resolved that the crater count — and the age estimates that emerge from it — are the most accurate to date. The bright material of the dome is made up of much younger material, about four million years old.

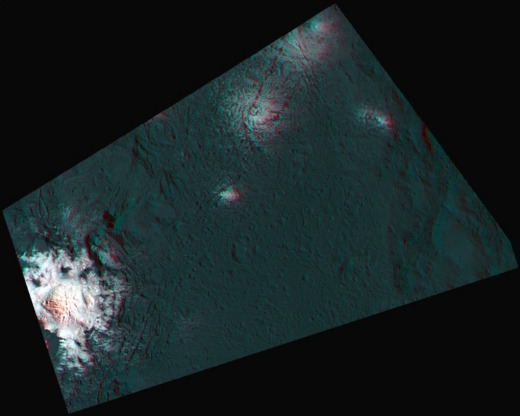

Image: This 3d-anaglyph for the first time shows a part of Occator crater in a combination of anaglyphe and false-color image. NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA.

Domes like this, interpreted as signs of cryovolcanism, appear on the Jovian moons Callisto and Ganymede, and the new work argues that the same process is happening on Ceres. The original Occator impact would have caused subsurface brine to move closer to the surface, allowing water and dissolved gases to form a system of vents. Fractures on the surface formed, from which brine began to erupt, depositing salts that led to the formation of the dome.

The process may still be active, though at a much lower level. Imagery of the area at certain angles has revealed what appears to be haze, a phenomenon the researchers explain as the result of sublimating water ice. Imagery from Dawn taken at distances as far as 14000 kilometers have shown unmistakeable variations in brightness that follow a diurnal rhythm. Says Guneshwar Singh Thangjam (MPS):

“The nature of the light scattering at the bottom of Occator differs fundamentally from that at other parts of the Ceres surface. The most likely explanation is that near the crater floor an optically thin, semi-transparent haze is formed.”

I should add, though, that there is a great deal we have yet to learn about this haze, as explained in one of two papers on this work:

The available data are insufficient for an analysis of the optical properties of this haze, but it is most likely an optically thin and semi-transparent layer forming at near-surface level. Diurnal albedo variations that correspond to Occator’s longitude have been detected by radial velocity changes (Molaro et al. 2016) supporting the existence of a temporarily varying haze layer. The detection of water-ice signatures at Oxo [a second crater at which haze has been detected] further supports ongoing sublimation activities on Ceres. Although we expect the maximum haze concentration above the central spot in Occator, it is remarkable that our data also indicate activity at the secondary spots.

The water sublimation, and thus the intensity of the haze, varies with the degree of sunlight. This explanation makes Ceres the closest body to the Sun that experiences cryovolcanism. It is the age difference — the bright deposits are 30 million years younger than the crater — as well as the distribution of the bright material within the crater itself, that tells us how active Occator crater has been and, on a much smaller scale, continues to be to this day.

The paper is Nathues et al., “Evolution of Occator Crater on (1)Ceres,” The Astronomical Journal Volume 153, Number 3 (17 February, 2017). Abstract available. See also G. Thangjam et al., “Haze at Occator Crater on Dwarf Planet Ceres,” The Astrophysical Journal Letters Volume 833, Number 2 (15 December, 2016). Abstract / Preprint.

Fragmented Asteroid Develops Comet-like Tails

You wouldn’t expect main belt asteroids to develop tails like comets — their orbits are circular enough that they don’t undergo the kind of temperature swings many comets experience in their plunge toward perihelion — but we do have some twenty cases of asteroids that do exactly that. The photo below, showing imagery from the 10.4-meter Great Canary Telescope, gives us views of asteroid P/2016 G1, with a smudgy dust trail splayed out behind the object.

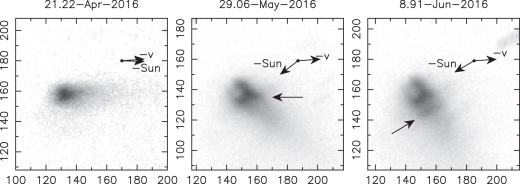

Image: Asteroid P/2016 G1 at three different times in 2016: late April, late May and mid June. The arrow in the center panel points out an asymmetric feature that can be explained if the asteroid initially ejected material in a single direction, perhaps due to an impact. Credit: Fernando Moreno (Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia, Spain).

Moreno and team, who have specialized in the dust environment near main belt objects, have now uncovered another intriguing asteroid, this one with an even more curious tail. Asteroid P/2016 J1 turns out to be an asteroid pair, of a kind that seem to occur not infrequently in the main belt. The likely origin of the pair is an impact that broke a single asteroid into two parts, but astronomers studying the object also believe it could have fragmented because of an excess of rotational speed. Asteroid pairs gradually drift apart from each other, their gravitational link not strong enough to hold them together, but they remain in roughly similar orbits around the Sun.

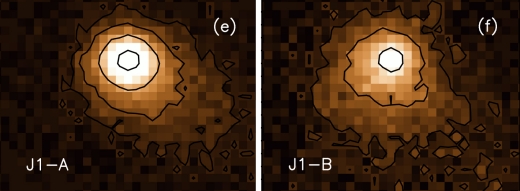

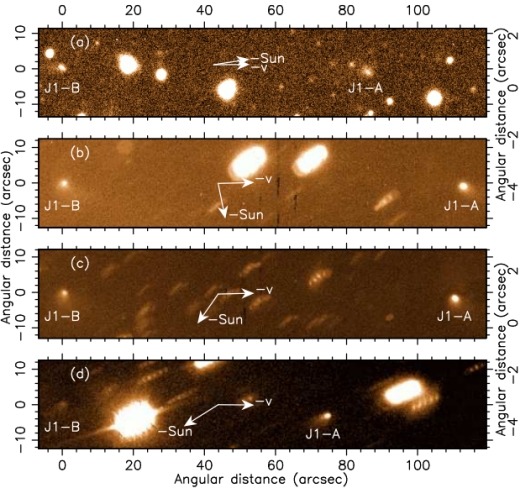

Image: Images of the P/2016 J1 asteroid pair taken on May 15th, 2016. They show a central region, the asteroid, and a diffuse blot corresponding to the dust tail. Credit: Moreno et al.

Moreno notes what makes P/2016 J1 unusual: Both fragments show dust structures similar to a comet, making this the first time we have seen an asteroid pair undergoing simultaneous activity. Both elements of the pair became activated near perihelion, between the end of 2015 and the beginning of 2016, and they displayed their tail-like structures for up to nine months.

Moreno and team used the Great Telescope of the Canary Islands (GTC) and the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) to study the P/2016 J1 pair, discovering that the asteroid fragmented about six years ago, based on analysis of its orbital evolution. This makes it the youngest asteroid pair known. The asteroid pair takes 5.65 years to complete an orbit, meaning that the fragmentation would have occurred on the previous orbit.

Image: This is part of Figure 1 from Moreno et al.’s paper on P/2016 J1. Images of P/2016 J1-A and J1-B obtained with MegaCam on the 3.6m CanadaFrance-Hawaii-Telescope on March 17, 2016 (a), and with OSIRIS at the 10.4m Gran Telescopio Canarias on May 15, 2016, May 29, 2016, and July 31, 2016 (b,c,d). In panels (a),(b),(c), and (d), the physical dimensions are 170982×33925, 133788×26545, 135616×26908, and 184964×36699 km, respectively. Credit: Moreno et al.

The tail is not directly caused by the original fragmentation, but seems to have happened as an after-effect. Moreno believes we are looking at dust emissions caused by the sublimation of ice that was originally exposed by the breakup. This contrasts with the earlier asteroid tail on P/2016 G1, which Moreno and colleagues believe was the result of an impact. The team’s models show that the ejected material on P/2016 G1 was not isotropically emitted.

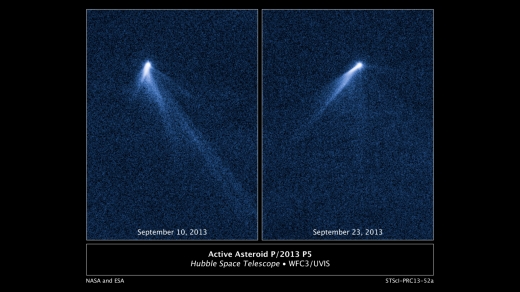

Image: Another view of an activated asteroid with a tail, this one showing Hubble Space Telescope images of the asteroid P/2013P5. Credit: NASA/ESA.

The paper on P/2016 J1 is Moreno et al., “The splitting of double-component active asteroid p/2016 J1 (PANSTARRS),” The Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 837, No. 1 (2017). Abstract / preprint. The paper on P/2016 G1 is Moreno et al., “Early Evolution of Disrupted Asteroid P/2016 G1 (PANSTARRS),” The Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 836 No. 2 (2016). Abstract / preprint.