Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Perspectives on Cosmic Archaeology

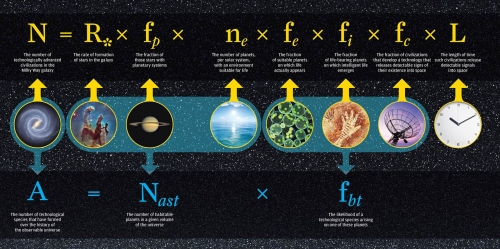

I’ve always found the final factor in the Drake Equation to be the most telling. Trying to get a rough idea of how many other civilizations there might be in the galaxy, Drake looked at factors ranging from the rate of star formation to the fraction of planets suitable for life on which life actually appears. Some of these items, like the fraction of stars with planets, are being clarified almost by the day with continuing work. But the big one at the end — the lifetime of a technological civilization — remains a mystery.

By ‘technological,’ Drake was referring to those civilizations that were capable of producing detectable signals; i.e., releasing electromagnetic radiation into space. And when we have but one civilization to work with as example, we’re hard pressed to know what this factor is. This is where Adam Frank (University of Rochester) and Woodruff Sullivan (University of Washington, Seattle) come into the picture. In a new paper in Astrobiology, the researchers argue that there are other ways of addressing the ‘lifetime’ question.

Image credit: http://www.ForestWander.com [CC BY-SA 3.0 us], via Wikimedia Commons.

What Came Before Us

The idea is to calculate how unlikely our advanced civilization would be if none has ever arisen before us. In other words, Frank and Sullivan want to put a lower limit on the probability that technological species have, at any time in the past, evolved elsewhere than on Earth. Here’s how their paper describes this quest:

Standard astrobiological discussions of intelligent life focus on how many technological species currently exist with which we might communicate (Vakoch and Dowd, 2015). But rather than asking whether we are now alone, we ask whether we are the only technological species that has ever arisen. Such an approach allows us to set limits on what might be called the ”cosmic archaeological question”: How often in the history of the Universe has evolution ever led to a technological species, whether short- or long-lived? As we shall show, providing constraints on an answer to this question has profound philosophical and practical implications.

To do this, the authors produce their own equation drawing on Drake’s. Consider A the number of technological civilizations that have formed over the history of the observable universe. Rather than dealing with Drake’s factor L — the lifetime of a technological civilization — Frank and Sullivan propose what they call an ‘archaeological form’ of Drake’s equation. The need for the L factor disappears. The new equation appears in this form:

A = Nast * fbt

Where A = The number of technological species that have evolved at any time in the universe’s past

Nast = The number of habitable planets in a given volume of the universe

fbt = The likelihood of a technological species arising on one of these planets.

You can see that what Frank and Sullivan rely on are recent advances in the detection and characterization of exoplanets. We’re learning a great deal more about how common planets are and how many are likely to orbit in the habitable zone around their star, where liquid water could exist. Their term Nast relies on this work and draws together various terms from the original Drake equation including the total number of stars, the fraction of those stars that form planets, and the average number of planets in the habitable zone of their stars.

From the paper:

With our approach we have, for the first time, provided a quantitative and empirically constrained limit on what it means to be pessimistic about the likelihood of another technological species ever having arisen in the history of the Universe. We have done so by segregating newly measured astrophysical factors from the fully unconstrained biotechnical ones, and by shifting the focus toward a question of ”cosmic archaeology” and away from technological species lifetimes. Our constraint addresses an issue that is of particular scientific and philosophical consequence: the question ”Have they ever existed?” rather than the usual narrower concern of the Drake equation, ”Do they exist now?”

The paper is short and interesting; I commend it to you. The result it produces is that human civilization can be considered unique in the cosmos only if the odds of a civilization developing are less than one part in 10 to the 22nd power. Frank and Sullivan call this the ‘pessimism’ line. If the probability of a technological civilization developing is greater than this standard, then we can assume civilizations have formed before us at some time in the universe’s history.

And yes, this is a tiny number — one in ten billion trillion. Frank says in this University of Rochester news release that he believes it implies technology-producing species have evolved before us. Even if the chances of civilization arising were one in a trillion, there would be about ten billion civilizations in the observable universe since the first one arose. As for our own galaxy, another civilization is likely to have appeared at some point in its history if the odds against it evolving on any one habitable planet are better than one in 60 billion.

We fall back on cosmic archaeology in suggesting that given the size and age of the universe, Drake’s factor L may still play havoc with our chances of ever contacting another civilization. Sullivan puts it this way:

“The universe is more than 13 billion years old. That means that even if there have been a thousand civilizations in our own galaxy, if they live only as long as we have been around—roughly ten thousand years—then all of them are likely already extinct. And others won’t evolve until we are long gone. For us to have much chance of success in finding another “contemporary” active technological civilization, on average they must last much longer than our present lifetime.”

We can play with this a bit. Taking the Milky Way and choosing a probability of 3 X 10-9, we are likely to be one of hundreds of civilizations that have arisen. But drop that probability to 10-18 (one in a billion billion) and we are likely the first advanced civilization in the galaxy. Yet even with the latter constraint, that would still mean we are one of thousands of civilizations that have developed at some time in the visible universe.

I always appreciate work that frames an issue in a new perspective, which is what Frank and Sullivan’s paper does. We can’t know whether there are other civilizations currently active in our galaxy, but it appears that the odds favor their having arisen at some time in the past. In fact, these numbers show us that we are almost certainly not the first technological civilization to have emerged. Is the galaxy filled with the ruins of civilizations that were unable to survive, or is it a place where some cultures have mastered the art of keeping themselves alive?

The paper is Frank and Sullivan, “A New Empirical Constraint on the Prevalence

of Technological Species in the Universe,” Astrobiology Vol. 16, No. 5 (2016). Preprint available.

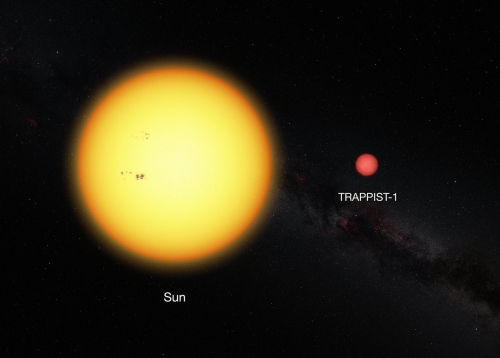

TRAPPIST-1: Three Nearby Worlds

About forty light years from Earth in the constellation Aquarius is the star designated 2MASS J23062928-0502285, which as of today qualifies as perhaps the most interesting ultracool dwarf we’ve yet found. What we learn in a new paper in Nature is that the star, also known as TRAPPIST-1 after the European Southern Observatory’s TRAPPIST telescope at La Silla, is orbited by three planets that are roughly the size of the Earth. We may have a world of astrobiological interest — and conceivably several — orbiting this tiny, faint star.

Image: Comparison between the Sun and the ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST-1. Credit: ESO.

If we untangle the TRAPPIST acronym, we find that it refers not to an order of monks (famous for their beers) but to the TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope, a 60 cm robotic instrument that is operated from a control room in Liège, Belgium. TRAPPIST homes in on sixty nearby dwarf stars at infrared wavelengths to search for planets. Michaël Gillon, who led the team from the University of Liège that made the recent discovery, nails its significance:

“Why are we trying to detect Earth-like planets around the smallest and coolest stars in the solar neighbourhood? The reason is simple: systems around these tiny stars are the only places where we can detect life on an Earth-sized exoplanet with our current technology. So if we want to find life elsewhere in the Universe, this is where we should start to look.”

In other words, life may exist on many worlds, and many of us believe that it does. But at our current level of equipment and expertise, a star like TRAPPIST-1 is significant because the star is small and dim enough for the atmospheres of Earth-sized planets to be studied. We learn from the Nature paper that two of the planets here have orbital periods of 1.5 days and 2.4 days respectively. The third is not as well characterized, with its orbit in a range from 4.5 to 73 days despite follow-up work with ESO’s 8-metre Very Large Telescope in Chile.

Noting how close the planets are to the host star, Gillon likens the scale of the system to that of Jupiter and its larger moons. These are worlds twenty to one hundred times closer to their star than the Earth is to the Sun, but the two inner planets receive only twice and four times respectively the stellar radiation that the Earth receives from the Sun. That puts them too close to the star to be in the habitable zone, while the outer planet may possibly lie within it.

But bear in mind that at least the inner two planets are probably tidally locked, with one side perpetually facing the star, the other turned away from it. Hence there may be regions near the terminator that receive daylight but maintain relatively cool temperatures. Given that the third planet may turn out to be entirely within the habitable zone, we have a fascinating test case for upcoming attempts to characterize the atmospheres of each of these Earth-sized worlds.

Image: Artist’s impression of the ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST-1 from close to one of its planets. Credit: ESO.

This ESO news release quotes Julien de Wit, a co-author of the paper on this work, with regard to where we go next:

“Thanks to several giant telescopes currently under construction, including ESO’s E-ELT and the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope due to launch for 2018, we will soon be able to study the atmospheric composition of these planets and to explore them first for water, then for traces of biological activity. That’s a giant step in the search for life in the Universe.”

The paper is Gillon et al., “Temperate Earth-sized Planets Transiting a Nearby Ultracool Dwarf Star,” published online in Nature 2 May 2016 (abstract). I’ll note too the continuing interest Centauri Dreams reader Harry R. Ray has shown in TRAPPIST 1, and thank him for bringing it to my attention before these first news reports surfaced.

Spacecoaches and Beamed Power

If you’re planning to make it to the International Space Development Conference in San Juan, Puerto Rico next month, be advised that Brian McConnell will be there with thoughts on a subject we’ve discussed in several earlier posts: A ‘spacecoach’ that uses water as a propellant and offers a practical way to move large payloads (and crews) around the Solar System. Based in San Francisco, Brian is a technology entrepreneur who doubles as a software/electrical engineer. In the essay below, he looks at the spacecoach in relation to the Breakthrough Starshot initiative, where synergies come into play that may benefit both concepts.

by Brian McConnell

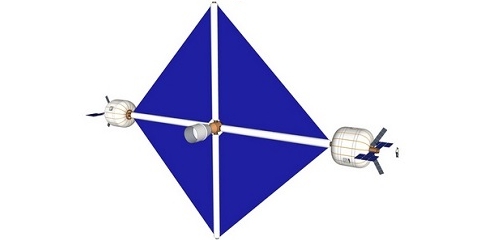

The spacecoach is a design pattern for a reusable solar electric spacecraft, previously featured on Centauri Dreams here and developed in A Design for a Reusable Water-Based Spacecraft Known as the Spacecoach (Springer Verlag), which I wrote with Alex Tolley. It primarily uses water as its propellant. This design has numerous benefits, chief among them the ability to turn consumables, ordinarily deadweight, into working mass.

The recent announcement of the Breakthrough Starshot project, which aims to use beamed power to drive ultra lightweight lightsail probes on interstellar trajectories, is of note. This same infrastructure could be used to augment the capabilities and range of spacecoaches (or any solar electric spacecraft), while providing a near-term use for beamed power infrastructure as it is developed and scaled up.

The spacecoach design pattern combines a medium sized solar array (sized to generate between 500 kilowatts and 2 megawatts of peak power at 1AU) with electric propulsion units that use water as propellant (and possibly also waste streams such as carbon dioxide, ammonia, etc). We found that, even when constrained to these power levels, they could fly approximately Hohmann trajectories to and from destinations in the inner solar system. Because consumables are converted into propellant, this reduces mass budgets by an order of magnitude, and effectively eliminates the need for an external interplanetary stage, all while greatly simplifying the logistics of supporting a sizeable crew for long duration missions (more consumables = more propellant).

The primary constraint for space coaches, especially if you want to travel to the outer solar system, is available power. This is an issue for two reasons. First, solar flux drops off by 1/r2, so at Jupiter, a solar array will generate roughly 1/25th the power as it does at Earth distance. Second, trips to more distant locations will typically require a greater delta V (and thus higher exhaust velocity to achieve this with a given amount of propellant). The amount of energy required to generate a unit of impulse scales linearly with exhaust velocity, so the net result is the ship’s power requirements are increased, all while the powerplant’s power density (watts per kilogram of solar array) is decreased.

Testing Beamed Power

Beamed power infrastructure would enable space coaches and solar electric spacecraft in general to operate at higher power levels for a given array size, which would enable them to operate at higher thrust levels, and to utilize higher exhaust velocities to maximize delta V and propellant efficiency. This means they would be able to accelerate faster, achieve higher delta-v, while using less propellant. In effect beamed power to SEP spacecraft will give their operators the equivalent of a nuclear electric power plant (without the nukes).

A spacecoach built for solar only operation would be able to serve as a testbed for beamed power. For example, a space coach departing Earth orbit could be illuminated with a beam that increases its power output by a small amount, say 10% (large enough to make a measurable difference in performance, yet small enough that major modifications are not required to the ship as it just experiences slightly brighter illumination while in beam). At higher light levels, this technique could also be used to simulate lighting and heat loading conditions expected at the inner planets while remaining in near Earth space. Note also that lasers can be tuned to the absorption wavelength(s) of the photovoltaic material, greatly improving conversion efficiency (and reducing heat gain per unit of power delivered). An even cheaper way to build out and test power beaming infrastructure will be with satellites and probes that utilize solar electric propulsion.

The pathway to a system based primarily on beamed power then becomes one based on incremental improvements, both for the ground based facilities and for the ships. This would result in near term applications for the beamed power facilities while the much more technically challenging aspects of the starshot project are sorted out. Meanwhile, satellite and space coach operators could test ships with ever higher levels of beamed power until they hit a limit (heat rejection is probably the main limit to how much power can be concentrated per unit of sail area, as this is similar to concentrated photovoltaics).

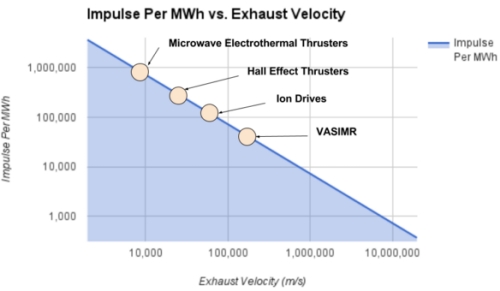

The chart below illustrates the power/performance curve by showing the amount of impulse that can theoretically be generated per megawatt hour using electric propulsion, as a function of exhaust velocity. Real world performance will be somewhat lower due to efficiency losses, but this shows the relationship between thrust, ve and power. We see that impulse per MWh varies from 72,000 kg-m/s (ion drive, ve ~ 100,000 m/s) to 1,400,000 kg-m/s (RF arcjet, ve ~ 5000 m/s). A Hall Effect thruster, a flight proven technology, would yield about 300,000 kg-m/s per MWh. Compare this to pure photonic propulsion, which would yield only 12 to 24 kg-m/s per MWh. Clearly photonic propulsion will be necessary to achieve a delta v of 0.2c, but for more pedestrian applications such as satellite orbit raising, launching interplanetary probes or cargo ships from LEO to BEO (beyond earth orbit), electric propulsion will work well at power levels many orders of magnitude lower than what’s required for a starshot.

Driver for an Interplanetary Infrastructure?

Closer to home there could be lots of opportunities to sell beamed power to space operators. It’s costly to launch large payloads beyond low earth orbit (which isn’t cheap in the first place). Meanwhile, payload fairings limit the size of self-deploying solar arrays, which limits the use of electric propulsion for satellites and probes. If one could launch spacecraft with small solar arrays to LEO, and then use beamed power to amplify their power budget they could use electric propulsion to boost themselves to their desired orbits or interplanetary trajectories within a reasonable time frame. The beamed power infrastructure can also be built up incrementally. Early systems would beam 100 kilowatts to 10 megawatts of power to targets measuring meters to tens of meters in diameter. This should be readily achievable, and can be scaled up from there in terms of power output, beam precision, etc. The result: lower costs per kilogram to deliver a payload to its destination or desired orbit compared to all chemical propulsion.

This could make electric propulsion for transit from LEO to GEO and beyond an attractive option. Meanwhile, the power beaming operator would accrue lots of operational experience with beam shaping, tracking objects in orbit, etc, all things that will need to be mastered for the starshot project, while providing an economic foundation for the power beaming facilities during the buildup to their intended purpose.

In fact, one can imagine the starshot project becoming a profitable LEO to BEO (beyond earth orbit) launch operator in its own right. The terrestrial power beaming infrastructure is one component. A standardized “power sail” that can be fitted to many different payloads, from geostationary satellites to interplanetary probes, is another. The power sail would consist of a self-deploying solar array that is sized to work well with beamed power, heat rejection gear, and electric propulsion units. It would use beamed power during its boost phase to rapidly accrue velocity for its planned trajectory, and then as it leaves near Earth space, would transition to use ambient light as its power source from there. Meanwhile these power sails would provide an evolutionary path from conventional spacecraft to solar electric propulsion to the nanocraft envisioned for purely photonic propulsion.

As a starting point, it would be interesting to conduct ground based vacuum chamber tests to see how a variety of PV materials respond to being illuminated with concentrated laser light tuned to their peak absorption wavelengths. What do the conversion efficiencies look like? How much waste heat is generated? How do the materials perform at high temperatures in simulated in-beam conditions? Building on that one can imagine experiments involving cubesats to validate the data from those experiments in real world conditions, and if that all works out, one could scale up from there to build out beamed power infrastructure for use by many types of solar electric vehicles.

Ambitious R&D projects have a way of generating unintended side benefits. It’s possible that the starshot initiative, in addition to being our first step toward the stars, will also make great contributions to travel and exploration within the solar system.

Light’s Echo: Protoplanetary Disk Examined

The star YLW 16B, about 400 light years from the Earth, has roughly the same mass as the Sun. But unlike the Sun, a mature 4.6 billion year old star, YLW 16B is a scant million years old, a variable of the class known as T Tauri stars. Whereas our star is relatively stable in terms of radiation emission, the younger star shows readily detectable changes in radiation, a fact that astronomers have now used in combining data from the Spitzer space telescope with four ground-based instruments to learn more about the dimensions of its protoplanetary disk.

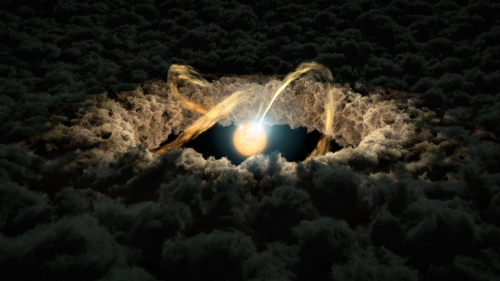

Image: This illustration shows a star surrounded by a protoplanetary disk. Material from the thick disk flows along the star’s magnetic field lines and is deposited onto the star’s surface. When material hits the star, it lights up brightly. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

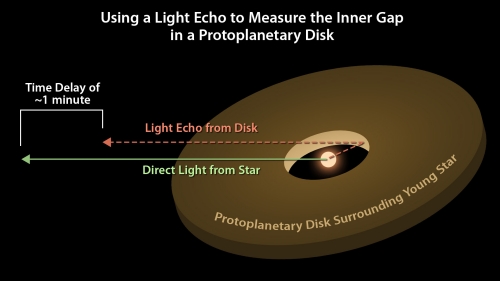

The method is called photo reverberation, and it takes advantage of the fact that when the star brightens as material from the turbulent disk falls onto its surface, some of the emitted light strikes the disk. The result is what is known as a ‘light echo,’ a delayed flash that can be used to measure how far the star is from the inner edge of the surrounding disk.

The time lag between the stellar emissions and their ‘echoes’ is what is in play here. Over the course of a two-night observing period, the researchers found consistent time lags between emissions and echoes. On the ground, the Mayall telescope at Kitt Peak (Arizona), the Harold L. Johnson telescope in Mexico and the SOAR and SMARTS telescopes in Chile could measure shorter-wavelength infrared wavelengths — these emissions came from the star. Spitzer, meanwhile, measured longer-wavelength light from the disk’s echo. From the paper:

Near-simultaneous time-series photometric observations were conducted on April 20, 22, and 24, 2010, with four ground-based telescopes operating in H and K bands and the Spitzer Space Telescope observing at 4.5 µm. Each session of Spitzer staring mode monitoring lasted ?8 hours. One (YLW 16B) out of twenty-seven sources detected was found to have mutually correlated hourly variations in all three wavebands. Over all three nights, the time series measurements of YLW 16B in H and K bands are consistently synchronized, while the light curve at 4.5 µm lags behind both H and K by 74.5±3.2 seconds over the first two nights when we have usable 4.5 µm data.

From this we learn that the light must have traveled about 0.084 AU between emission and echo (with an uncertainty on the order of 0.01 AU), meaning the inner edge of the protoplanetary disk reaches in as far as one-quarter the diameter of Mercury’s orbit. The paper notes that the structure of the inner region of a protoplanetary disk depends on the mechanism by which material from the disk accretes onto the star. At work at this inner boundary is sublimation, affecting dust, and the forces of the stellar magnetosphere that shape gas distribution.

Image: The star’s irregular illumination allows astronomers to measure the gap between the disk and the star by using a technique called “photo-reverberation” or “light echoes.” First, astronomers look at how much time it takes for light from the star to arrive at Earth. Then, they compare that with the time it takes for light from the star to bounce off the inner edge of the disk and then arrive at Earth. That time difference is used to measure distance, as the speed of light is constant. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

We’ve learned much about disk structure by studying disks around larger mass stars, but until now probing into the inner disk regions of pre-main sequence T Tauri stars like YLW 16B has been hampered by the proximity of the inner disk edge to the star, too small to be directly imaged. Measuring the light travel time from the young star to the inner disk wall thus breaks new ground. The authors believe the method is viable for other young stars that show variability in the near-infrared, giving us a way to measure disks where planet formation has yet to begin.

For more on light echoes, see ‘Light Echo’ Reveals Eta Carinae Puzzle, which looks at the technique in terms of supernovae. To my knowledge, this is the first time light echoes have been studied in relation to protoplanetary disks. The paper is Meng et al., “Photo-reverberation Mapping of a Protoplanetary Accretion Disk around a T Tauri Star,” accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal (preprint). A JPL news release is also available.

Beneath a Methane Sea

Back when Cassini was approaching Saturn and we all anticipated the arrival of the Huygens payload on the surface, speculation grew that rather than finding a solid surface, Huygens might ‘splash down’ in a hydrocarbon sea. I can remember art to that effect in various Internet venues of the time. In the event, Huygens came down on hard terrain, but since then Cassini’s continuing surveys have shown that seas and lakes do exist on the moon. Over 1.6 million square kilometers (about two percent of the surface of Titan) are covered in liquid.

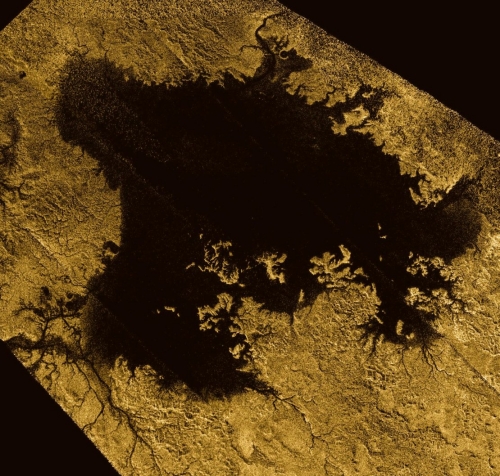

Image: Ligeia Mare, shown here in a false-colour image from the international Cassini mission, is the second largest known body of liquid on Saturn’s moon Titan. It measures roughly 420 km x 350 km and its shorelines extend for over 3,000 km. It is filled with liquid methane. The mosaic shown here is composed from synthetic aperture radar images from flybys between February 2006 and April 2007. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/Cornell.

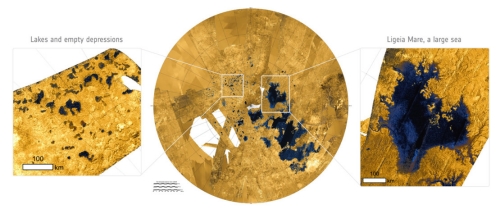

The liquid, of course, is not water but methane and ethane, existing in an atmosphere that is almost 95 percent nitrogen (with methane, small amounts of hydrogen and ethane making up the rest). Cassini has shown us three large seas near the north pole that are surrounded by numerous smaller lakes, while only a single lake has thus far been found in the southern hemisphere. New work on Cassini flyby data between 2007 and 2015 now confirms that Ligeia Mare, one of Titan’s largest seas, is made up primarily of liquid methane.

Image: A radar image of Titan’s north polar regions (centre), with close ups of numerous lakes (left) and a large sea (right). The sea, Ligeia Mare, measures roughly 420 x 350 km and is the second largest known body of liquid hydrocarbons on Titan. Its shorelines extend for some 2000 km and many rivers can be seen draining into the sea. By contrast, the numerous lakes are typically less than 100 km across and have more rounded shapes with steep sides. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/USGS; left and right: NASA/ESA. Acknowledgement: T. Cornet, ESA.

The finding is a bit surprising given that ethane is produced when sunlight breaks methane molecules apart. Thus expectations for Ligeia Mare involved primarily ethane. Alice Le Gall (Laboratoire Atmosphères, Milieux, Observations Spatiales and Université Versailles Saint-Quentin, France), who led the new study, comments on the finding:

“Either Ligeia Mare is replenished by fresh methane rainfall, or something is removing ethane from it. It is possible that the ethane ends up in the undersea crust, or that it somehow flows into the adjacent sea, Kraken Mare, but that will require further investigation.”

As this work progressed, Le Gall and team relied on a radio sounding experiment performed in 2013, described in this ESA news release. The radio sounding, led by Marco Mastrogiuseppe, detected seafloor echoes and was able to derive the depth of Ligeia Mare along Cassini’s track, which marked the first time we have ever detected the bottom of an off-Earth sea. The deepest depth recorded was 160 meters. Le Gall used the sounding data along with observations of thermal emissions from Ligeia Mare at microwave wavelengths in her work.

The result: The new paper reports that the researchers were able to separate the thermal emissions from the seafloor from those of the liquid sea. The seabed is found to be covered by what Le Gall calls “a sludge layer of organic-rich compounds.”

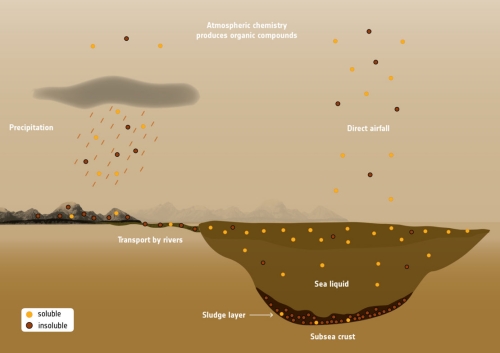

Image: How different organic compounds make their way to the seas and lakes on Titan, the largest moon of Saturn. A recent study revealed that Ligeia Mare, one of Titan’s three seas, consists of pure methane and has a seabed covered by sludge of organic-rich material. Credit: ESA.

You can see the process at work in the image above. Nitrogen and methane in Titan’s atmosphere produce organic molecules, the heaviest of which fall to the surface. Reaching the sea through rain or one of Titan’s rivers, some are dissolved, while others sink to the ocean floor. We also find that the surface areas surrounding the lakes and seas are likely flooded with liquid hydrocarbons, based on the lack of temperature change between the sea and the shore.

The paper is Le Gall et al., “Composition, seasonal change, and bathymetry of Ligeia Mare, Titan, derived from its microwave thermal emission,” Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, published online 25 February 2016 (abstract). Marco Mastrogiuseppe’s work on the depth of Ligeia Mare is described in “The bathymetry of a Titan sea,” Geophysical Research Letters, published online 4 March 2014 (abstract).

Gravitational Lensing with Planets

As we’ve been talking about the Sun’s gravitational focus, it’s interesting to reflect on the history of its study. Albert Einstein’s thinking about gravitational lensing in astronomy was explicitly addressed in a 1936 paper, but it wasn’t until 1964 that Stanford’s Sydney Liebes produced the mathematics behind lensing at the largest scale, working with the lensing caused by a galaxy between the Earth and a distant quasar. Dennis Walsh, a British astronomer, found the first actual quasar ‘image’ produced in this way back in 1978, with Von Eshleman’s study of the Sun’s lensing the following year including the idea of sending a spacecraft to 550 AU.

SETI was on Eshleman’s mind, for he pondered what could be done at the 21 cm wavelength, the SETI ‘waterhole,’ and so did Frank Drake, who presented a paper on the concept in 1987. If you have a good academic library near you, its holdings of the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society for 1994 will include the proceedings of the Conference on Space Missions and Astrodynamics that Claudio Maccone organized two years earlier. FOCAL was now being considered, though in a mission then called SETISAIL, even though SETI would be only one aspect of its scientific investigations.

FOCAL Beyond Stars

Finding ways to exploit the gravitational lens of the Sun forces us to take into account the Sun’s corona, a problem both Eshleman (Stanford) and Slava Turyshev (JPL) soon addressed. We’d like to get a spacecraft not just to 550 AU, but well beyond it to avoid coronal distortion, taking advantage of the fact that we are not dealing with a focal point but a focal line. Let me quote one of Claudio Maccone’s papers on this (citation at the end of this post):

…a simple, but very important consequence of the above discussion is that all points on the straight line beyond this minimal focal distance are foci too, because the light rays passing by the Sun further than the minimum distance have smaller deflection angles and thus come together at an even greater distance from the Sun.

Thus we have the ability to move well beyond 550 AU, and in fact have no choice but to do so. The Sun’s corona creates what Maccone calls a ‘diverging lens effect’ and opposes the converging effect we associate with a gravitational lens. The result is that the minimum distance the FOCAL craft must reach (here I’m paraphrasing the paper) is higher for lower frequencies (of the source electromagnetic waves crossing the Solar corona) and lower for higher frequencies. Thus at 500 GHz, the focus is about 650 AU. At 160 GHz, the focus is at 763 AU.

But are we limited to using the Sun and, if we build radio ‘bridges’ as discussed yesterday, nearby stars as gravitational lenses? It turns out that planets too can be used for this purpose. In his 2011 study of this idea, which appeared in Acta Astronautica, Maccone produces the needed equations, noting that the ratio of a planet’s radius squared to its mass lets us calculate the distance a spacecraft must reach to take advantage of planetary lensing. From that we have defined what he calls the planet’s focal sphere.

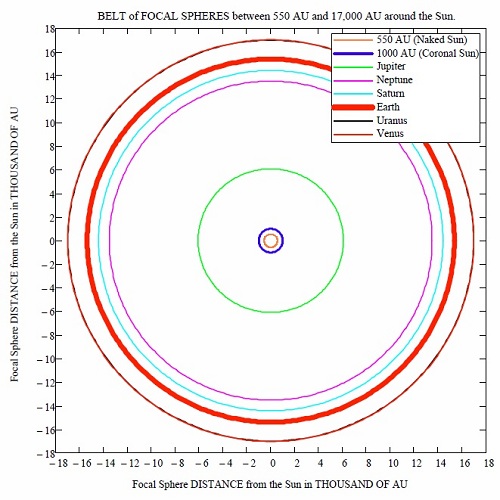

Image: The complete BELT of focal spheres between 550 and 17,000 AU from the Sun, as created by the gravitational lensing effect of the sun and all planets, here shown to scale. The discovery of this belt of focal spheres is the main result put forward in this paper, together with the computation of the relevant antenna gains. Credit: C. Maccone.

Lensing Moves into the Oort Cloud

The figure above may contain a few surprises. We would expect Jupiter to top the list of planetary lenses, and indeed, its focal sphere is the next out from the Sun at 6100 AU. That’s a useful number to keep in mind, because we may discover that the Sun’s coronal effects are simply too powerful to overcome to produce the needed images. If so, we have a target halfway out to the inner Oort Cloud that we can also use to study the lensing phenomenon.

Beyond this, notice that Neptune, which has a high ratio between the square of its radius and its mass, comes next, at 13,525 AU. Saturn’s focal sphere is 14,425 AU out, and next we find our own Earth, with a focal sphere at 15,375 AU. Our planet makes a better lensing candidate than Uranus because it is the body with the highest density (ratio of mass to volume) in the Solar System. Maccone likes to point out that because we know the Earth’s surface and atmosphere better than that of any other planet, a FOCAL mission using the Earth as a lens would begin with a significant advantage as we try to untangle a lensed image of a distant object.

How would we take advantage of these planetary focal spheres? They extend all the way out to 17,000 AU in the case of Venus. As the figure makes clear, a fast spacecraft departing the Solar System could examine any of them in turn, beginning with observations as the Sun’s coronal effects begin to subside. Noting that a spacecraft enroute to Alpha Centauri would cross all these focal spheres, Maccone muses on the results of such a crossing:

First of all, while the Sun does not move in the Sun-centered reference frame of the Solar system, all the planets do move. This means that they actually sweep a certain area of the sky, as seen from the spacecraft, so that a spacecraft enjoys a sort of moving magnifying lens. How many extrasolar planets would fall inside this moving magnifying lens? Well, we don’t know nowadays, of course, but the over 400 exoplanets found to date [the paper appeared in 2011] are a neat promise that many more such exoplanets could be detected anew by a suitably equipped spacecraft crossing the distances between 550 and 17,000 AU from the Sun thanks to the gravitational lenses of the planets.

Such discoveries would be serendipitous, to say the least, as our Alpha Centauri mission would just be seeing what happened to be in line with the planet being studied as it departed the system. But having Jupiter at 6100 AU and the Earth at 15,375 AU does offer us useful targets for experimentation with the technologies we’ll need to tease images out of a focal sphere encounter. One of the big if’s of Breakthrough Starshot is the construction of operation of the phased laser array. But if it is built and we can achieve velocities of a significant fraction of c, then dedicated missions to explore planetary lensing would be sensible.

Clearly the Sun is our first choice as a gravitational lens not just because of the relative proximity of its minimum focal distance (550 AU) but because the effective gain of the Sun is so much higher than that of Jupiter, and far higher than the low gain we could expect to achieve with the Earth as a gravitational lensing body. Maccone calculates numerical values for the gain at frequencies ranging from the hydrogen line up to the CMB peak at 160 GHz, evaluating each of these for the Sun’s gravitational lens as well as the focal spheres of the various planets. If we want to work with the lensing potential of planets, we’ll need major advances in antenna and imaging technologies to overcome the weak signatures the planets provide.

The paper is Maccone, “A New Belt Beyond Kuiper’s: A Belt of Focal Spheres Between 550 and 17,000 AU for SETI and Science,” Acta Astronautica Vol. 69, Issues 11-12 (December 2011), pp. 939-948 (abstract).