by Paul Gilster | Feb 23, 2018 | Exoplanetary Science |

At the last Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop, I was part of a session on biosignatures in exoplanet atmospheres that highlighted how careful we have to be before declaring we have found life. Given that, as Alex Tolley points out below, our own planet has been in its current state of oxygenation for a scant 12 percent of its existence, shouldn’t our methods include life detection in as wide a variety of atmospheres as possible? A Centauri Dreams regular, Alex addresses the question by looking at new work on chemical disequilibrium and its relation to biosignature detection. The author (with Brian McConnell) of A Design for a Reusable Water-Based Spacecraft Known as the Spacecoach (Springer, 2016), Alex is a lecturer in biology at the University of California. Just how close are we to an unambiguous biosignature detection, and on what kind of world will we find it?

by Alex Tolley

Image: Archaean or early Proterozoic Earth showing stromatolites in the foreground. Credit: Peter Sawyer / Smithsonian Institution.

The Kepler space telescope has established that exoplanets are abundant in our galaxy and that many stars have planets in their habitable zones (defined as having temperatures that potentially allow surface water). This has reinvigorated the quest to answer the age-old question “Are We Alone?”. While SETI attempts to answer that question by detecting intelligent signals, the Drake equation suggests that the emergence of intelligence is a subset of the planets where life has emerged. When we envisage such living worlds, the image that is often evoked is of a verdant paradise, with abundant plant life clothing the land and emitting oxygen to support respiring animals, much like our pre-space age visions of Venus.

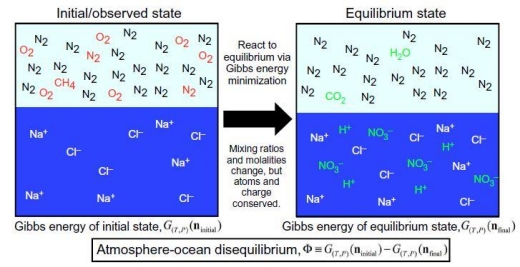

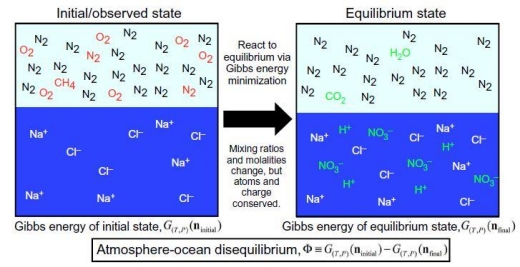

Naturally, much of the search for biosignatures has focused on oxygen (O2), whose production on Earth is now primarily produced by photosynthesis. Unfortunately, O2 can also be produced abiotically via photolysis of water, and therefore alone is not a conclusive biosignature. What is needed is a mixture of gases in disequilibrium that can only be maintained by biotic and not abiotic processes. Abiotic processes, unless continually sustained, will tend towards equilibrium. For example, on Earth, if life completely disappeared today, our nitrogen-oxygen dominated atmosphere would reach equilibrium with the oxygen bound as nitrate in the ocean.

Image: Schematic of methodology for calculating atmosphere-ocean disequilibrium. We quantify the disequilibrium of the atmosphere-ocean system by calculating the difference in Gibbs energy between the initial and final states. The species in this particular example show the important reactions to produce equilibrium for the Phanerozoic atmosphere-ocean system, namely, the reaction of N2, O2, and liquid water to form nitric acid, and methane oxidation to CO2 and H2O. Red species denote gases that change when reacted to equilibrium, whereas green species are created by equilibration. Details of aqueous carbonate system speciation are not shown. Credit: Krissansen-Totton et al. (citation below).

Another issue with looking for O2 is that it assumes a terrestrial biology. Other biologies may be different. However environments with large, sustained, chemical disequilibrium are more likely to be a product of biology.

A new paper digs into the issue. The work of Joshua Krissansen-Totton (University of Washington, Seattle), Stephanie Olson (UC-Riverside) and David C. Catling (UW-Seattle), the paper tackles a question the authors have addressed in an earlier paper:

“Chemical disequilibrium as a biosignature is appealing because unlike searching for biogenic gases specific to particular metabolisms, the chemical disequilibrium approach makes no assumptions about the underlying biochemistry. Instead, it is a generalized life-detection metric that rests only on the assumption that distinct metabolisms in a biosphere will produce waste gases that, with sufficient fluxes, will alter atmospheric composition and result in disequilibrium.”

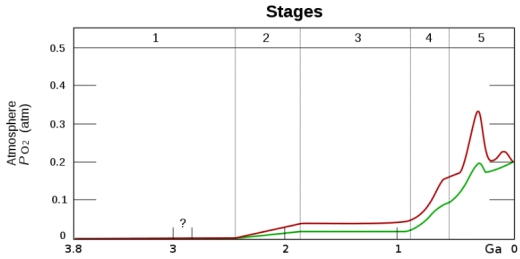

This approach also opens up the possibility of detecting many more life-bearing worlds as the Earth’s highly oxygenated atmosphere has only been in this state for about 12% of the Earth’s existence.

Image: Heinrich D. Holland derivative work: Loudubewe (talk) – Oxygenation-atm.svg, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12776502

With the absence of high partial pressures of O2 before the Pre-Cambrian, are there biogenic chemical disequilibrium conditions that can be discerned from the state of primordial atmospheres subject to purely abiotic equilibrium?

The new Krissansen-Totton et al? paper attempts to do that for the Archaean (4 – 2.5 gya) and Proterozoic (2.5 – 0.54) eons. Their approach is to calculate the Gibbs Free Energy (G), a metric of disequilibrium, for gases in an atmosphere-oceanic environment. The authors use a range of gas mixtures from the geologic record and determine the disequilibrium they represent using calculations of G for the observed versus the expected equilibrium concentrations of chemical species.

The authors note that almost all the G is in our ocean compartment from the nitrogen (N2)-O2 not reaching equilibrium as ionic nitrate. A small, but very important disequilibrium between methane (CH4) and O2 in the atmosphere is also considered a biosignature.

Using their approach, the authors look at the disequilibria in the atmosphere-ocean model in the earlier Archaean and Proterozoic eons. The geologic and model evidence suggests that the atmosphere was largely N2 and carbon dioxide (CO2), with a low concentration of O2 (2% or less partial pressure) in the Proterozoic.

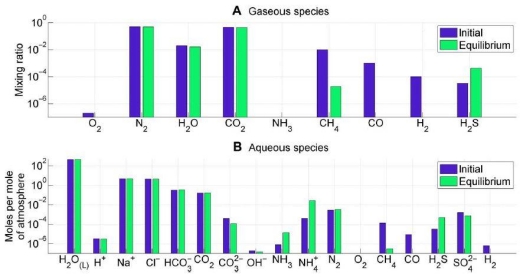

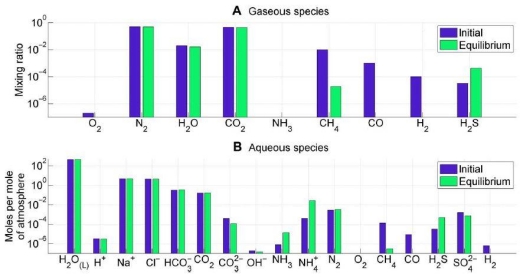

In the Proterozoic, as today, the major disequilibrium is due to the lack of nitrate in the oceans and therefore the higher concentrations of O2 in the atmosphere. Similarly, an excess concentration of CH4 that should quickly oxidize to CO2 at equilibrium. In the Archaean, prior to the increase in O2 from photosynthesis, the N2, CO2, CH4 and liquid H2O equilibrium should consume the CH4 and increase the concentration of ammonium ions (NH4+ ) and bicarbonate (HCO3-) in the ocean. The persistence of CH4 in both eons is primarily driven by methanogen bacteria.

Image: Atmosphere-ocean disequilibrium in in the Archean. Blue bars denote assumed initial abundances from the literature, and green bars denote equilibrium abundances calculated using Gibbs free energy minimization. Subplots separate (A) atmospheric species and (B) ocean species. The most important contribution to Archean disequilibrium is the coexistence of atmospheric CH4, N2, CO2, and liquid water. These four species are lessened in abundance by reaction to equilibrium to form aqueous HCO3 and NH4. Oxidation of CO and H2 also contributes to the overall Gibbs energy change. Credit: Krissansen-Totton et al.

Therefore a biosignature for such an anoxic world in a stage similar to our Archaean era, would be to observe an ocean coupled with N2, CO2 and CH4 in the atmosphere. There is however an argument that might make this biosignature ambiguous.

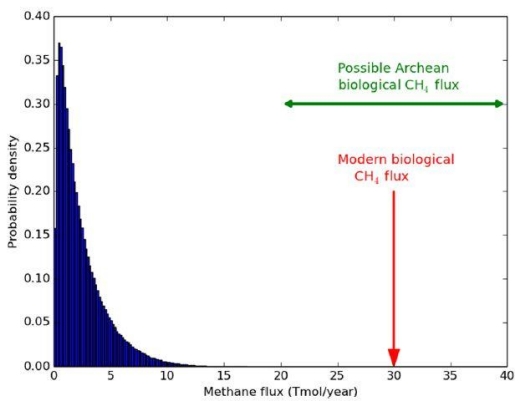

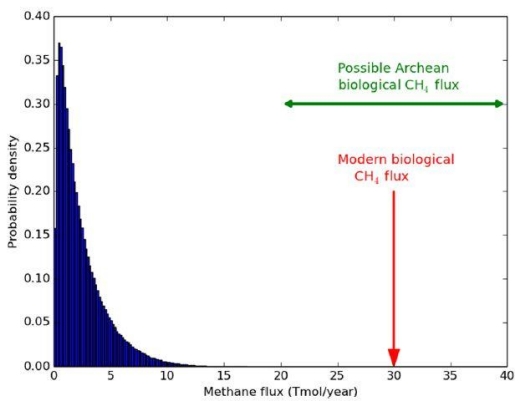

CH4 and carbon monoxide (CO) might be present due to impacts of bolides (Kasting). Similarly, under certain conditions, it is possible that the mantle might be able to outgas CH4. In both cases, CO would be present and indicative of an abiogenic process. On Earth, CO is consumed as a substrate by bacteria, so its presence should be absent on a living world, even should such outgassing or impacts occur. The issue of CH4 outgassing, at least on earth, is countered by the known rates of outgassing compared to the concentration of CH4 in the atmosphere and ocean. The argument is primarily about rates of CH4 production between abiotic and biotic processes. Supporting Kasting, the authors conclude that on Earth, abiotic rates of production of CH4 fall far short of the observed levels.

Image: Probability distribution for maximum abiotic methane production from serpentinization on Earth-like planets. This distribution was generated by sampling generous ranges for crustal production rates, FeO wt %, maximum fractional conversion of FeO to H2, and maximum fractional conversion of H2 to CH4, and then calculating the resultant methane flux 1 million times (see the main text). The modern biological flux (58) and plausible biological Archean flux (59) far exceed the maximum possible abiotic flux. These results support the hypothesis that the co-detection of abundant CH4 and CO2 on a habitable exoplanet is a plausible biosignature. Credit: Krissansen-Totton et al.

The authors conclude that their biosignature should also exclude the presence of CO to confirm the observed gases as a biosignature:

“The CH4-N2-CO2-H2O disequilibrium is thus a potentially detectable biosignature for Earth-like exoplanets with anoxic atmospheres and microbial biospheres. The simultaneous detection of abundant CH4 and CO2 (and the absence of CO) on an ostensibly habitable exoplanet would be strongly suggestive of biology.”

Given these gases in the presence of an ocean, can we use them to detect life on exoplanets?

Astronomers have been able to detect CO2, H2O, CH4 and CO in the atmosphere of HD 189733b, which is not Earthlike, but rather a hot Jupiter with a temperature of 1700F, far too hot for life. So far these gases have not been detectable on rocky worlds. Some new ground-based telescopes and the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope should have the capability of detecting these gases using transmission spectroscopy as these exoplanets transit their star.

It is important to note that the presence of an ocean is necessary to create high values of G. The Earth’s atmosphere alone has quite a low G, even compared to Mars. It is the presence of an ocean that results in G orders of magnitude larger than that from the atmosphere alone. Such an ocean is likely to be first detected by glints or the change in color of the planet as it rotates exposing different fractions of land and ocean.

An interesting observation of this approach is that a waterworld or ocean exoplanet might not show these biosignatures as the lack of weathering blocks the geologic carbon cycle and may preclude life’s emergence or long term survival. This theory might now be testable using spectroscopy and calculations for G.

This approach to biosignatures is applicable to our own solar system. As mentioned, Mars’ current G is greater than Earth’s atmosphere G. This is due to the photochemical disequilibrium of CO and O2. The detection of CH4 in Mars’ atmosphere, although at very low levels, would add to their calculation of Mars’ atmospheric G. In future, if the size of Mars’ early ocean can be inferred and gases in rocks extracted, the evidence for paleo life might be inferred. Fossil evidence of life would then confirm the approach.

Similarly, the composition of the plumes from Europa and Enceladus should also allow calculation of G for these icy moons and help to infer whether their subsurface oceans are abiotic or support life.

Within a decade, we may have convincing evidence of extraterrestrial life. If any of those worlds are not too distant, the possibility of studying that life directly in the future will be exciting.

The paper is Krissansen-Totton? et al., “Disequilibrium biosignatures over Earth history and implications for detecting exoplanet life,?” (2018)? Science Advances 4 ? (abstract? / ?full tex?t).

by Paul Gilster | Dec 29, 2017 | Sail Concepts |

Can we use the outflow of particles from the Sun to drive spacecraft, helping us build the Solar System infrastructure we’ll one day use as the base for deeper journeys into the cosmos? Jeff Greason, chairman of the board of the Tau Zero Foundation, presented his take on the idea at the recent Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop. The concept captured the attention of Centauri Dreams regular Alex Tolley, who here analyzes the notion, explains its differences from the conventional magnetic sail, and explores the implications of its development. Alex is co-author (with Brian McConnell) of A Design for a Reusable Water-Based Spacecraft Known as the Spacecoach (Springer, 2016), focusing on a new technology for Solar System expansion. A lecturer in biology at the University of California, he now takes us into a different propulsion strategy, one that could be an enabler for human missions near and far.

by Alex Tolley

Suppose I told you that a device you could make yourself would be a more energy efficient space drive than an ion engine with a far better thrust to weight ratio? Fantasy? No!

Such a drive exists. Called the plasma magnet, it is a development of the magnetic sail but with orders of magnitude less mass and a performance that offers, with constant supplied power, constant acceleration regardless of its distance from the sun.

At the recent Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop (TVIW), Jeff Greason presented this technology in his talk [1]. What caught my attention was the simplicity of this technology for propulsion, with a performance that exceeded more complex low thrust systems like ion engines and solar sails.

What is a plasma magnet?

The plasma magnet is a type of magsail that creates a kilometers wide, artificial magnetosphere that deflects the charged solar wind to provide thrust.

Unlike a classic magsail [9] (figure 1) that generates the magnetic field with a large diameter electrical circuit, the plasma magnet replaces the circular superconducting coil by inducing the current flow with the charged particles of the solar wind. It is an upgraded development of Robert Winglee’s Mini-Magnetospheric Plasma Propulsion (M2P2) [7, 8], a drive that required injection of charged particles to generate the magnetosphere. The plasma magnet requires no such injection of particles and is therefore potentially propellantless.

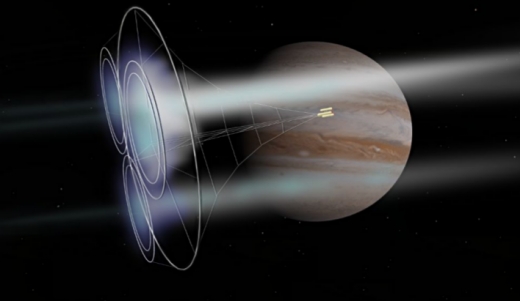

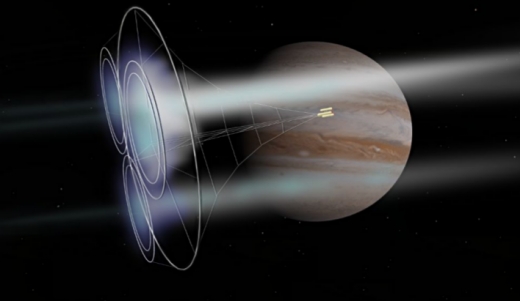

Figure 1. A triple loop magsail is accelerated near Jupiter. Three separate boost beams transfer momentum to the rig, carefully avoiding the spacecraft itself, which is attached to the drive sail by a tether. Artwork: Steve Bowers, Orion’s Arm.

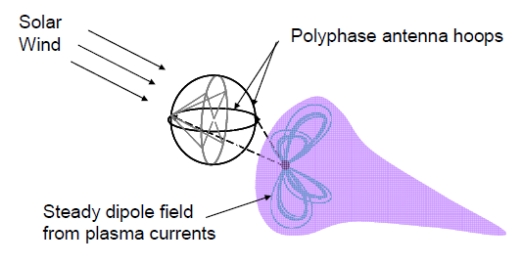

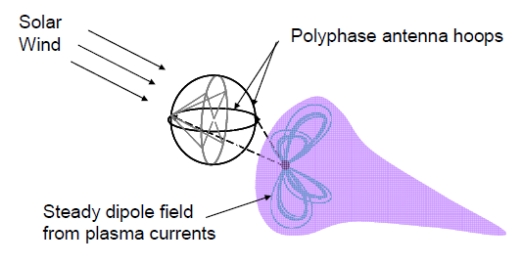

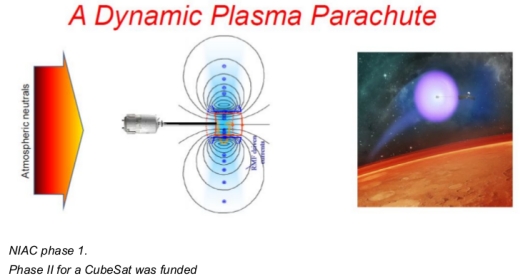

Developed by John Slough and others [5, 6], the plasma magnet drive has been validated by experimental results in a vacuum chamber and was a NIAC phase 1 project in the mid-2000s [6]. The drive works by initially creating a rotating magnetic field that in turns traps and entrains the charged solar wind to create a large diameter ring current, inducing a large scale magnetosphere. The drive coils of the reference design are small, about 10 centimeters in diameter. With 10 kW of electric power, the magnetosphere expands to about 30 kilometers in diameter at 1 AU, with enough magnetic force to deflect the solar wind pressure of about 1 nPa (1 nN/m2) which produces a thrust in the direction of the wind of about 1 newton (1N). Thrust is transmitted to the device by the magnetic fields, just as with the coupling of rotation in an electric motor (figure 2).

For a fixed system, the size of the induced magnetosphere depends on the local solar wind pressure. The magnetosphere expands in size as the solar wind density decreases further from the sun. This is similar to the effect of Janhunen’s electric sail [2] where the deflection area around the charged conducting wires increases as the solar wind density decreases. The plasma magnet’s thrust is the force of the solar wind pushing against the magnetosphere as it is deflected around it. It functions like a square-rigged sail running before the wind.

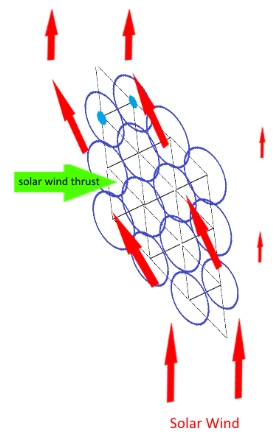

Figure 2. Plasma magnetic sail based on rotating magnetic field generated plasma currents. Two polyphase magnetic coils (stator) are used to drive steady ring currents in the local plasma (rotor) creating an expanding magnetized bubble. The expansion is halted by solar wind pressure in balance with the magnetic pressure from the driven currents (R >= 10 km). The antennas (radius ~ 0.1 m) are shown expanded for clarity. [6]

The engine is little more than 2 pairs of charged rotating coils and is therefore extremely simple and inexpensive. The mass of the reference engine is about 10 kg. Table 1 shows that the plasma magnet has an order higher thrust to weight ratio than an ion engine and 2 orders better than a solar sail. However, as the plasma magnet requires a power source, like the ion engine, the comparison to the solar sail should be made when the power supply is added, reducing is performance to a 10-fold improvement. [ A solar PV array of contemporary technology requires about 10 kg/kW, so the appropriate thrust/mass ratio of the plasma magnet is about 1 order of magnitude better than a solar sail at 1 AU]

The plasma magnet drive offers a “ridiculously high” thrust to weight ratio

The plasma magnet, as a space drive, has much better thrust to weight ratio than even the new X-3 Hall Effect ion engine currently in development. This ratio remains high when the power supply from solar array is added. Of more importance is that the plasma magnet is theoretically propellantless, providing thrust as long as the solar wind is flowing past the craft and power is supplied.

| Name | Type | Thrust/weight (N/kg)

Engine mass only | Thrust/weight (N/kg) with power supply |

| SSME | Chemical | 717 | N/A |

| RD-180 | Chemical | 769 | N/A |

| plasma magnetosphere | Electro-magnetic | 0.1 | .01 |

| NSTAR-1 | Ion (Gridded) | 0.004 | 0.002 |

| X-3 | Ion (Hall Effect) | 0.02 | 0.004 |

| Solar Sail | Photon Sail | 0.001 (at 1 AU) | N/A |

Table 1. Comparison of thrust to mass ratios of various types of propulsion systems. The power supply is assumed to be solar array with a 10 kg/kW performance.

The downside with the plasma magnet is that it can only produce thrust in the direction of the solar wind, away from the sun, and therefore can only climb up the gravity well. Unlike other propulsion systems, there is little capability to sail against the sun. While solar sails can tack by directing thrust against the orbital direction, allowing a return trajectory, this is not possible with the basic plasma magnet, requiring other propulsion systems for return trips.

Plasma magnet applications

1. Propulsion Assist

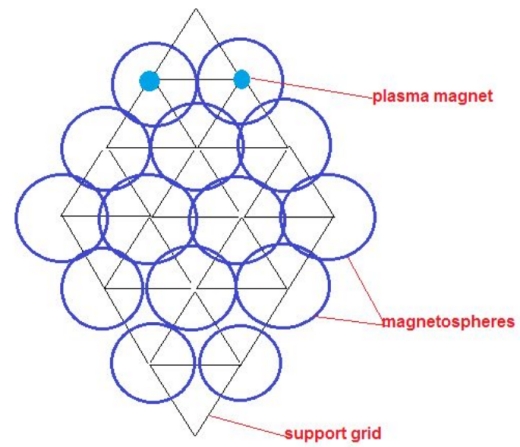

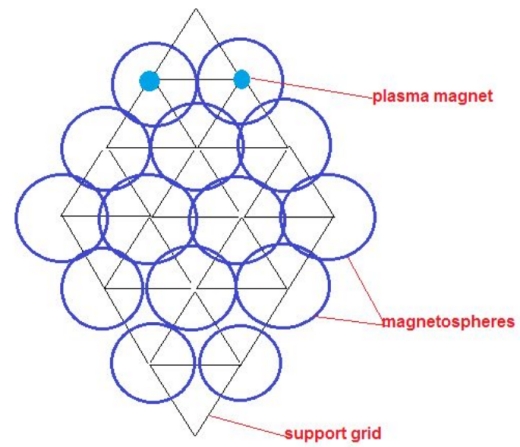

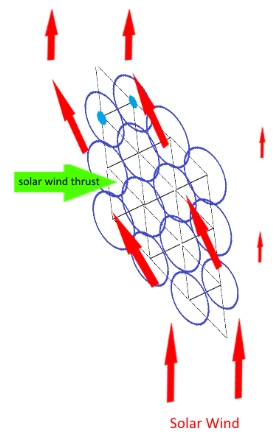

The most obvious use of the plasma magnet that can only be used to spiral out from the sun is as a propellantless assist. The drive is lightweight and inexpensive, and because it is propellantless, it can make a useful drive for small space probes. Because the drive creates a kilometers sized magnetosphere, scaling up the thrust involves increased power or using multiple drives that would need to be kept 10s of kilometers apart. Figure 3 shows a hypothetical gridded array. Alternatively, the plasma magnets might be separated by thrusters and individually attached to the payload by tethers.

Figure 3. Plasma magnets attached to the nodes in a 2D grid could be used to scale up the thrust. The spacecraft would be attached by shroud lines as in a solar sail with a trailing payload. Scaling up the power supply to create a larger magnetosphere is also possible.

For a mixed mode mission, the plasma magnet engine is turned on for the outward bound flight, with or without the main propulsion system turned on. The use of power to generate thrust without propellant improves the performance of propellant propulsion systems where the accumulated velocity exceeds the performance cost of the power supply mass or reduced propellant. For an ion engine as the main drive, the plasma magnet would use the same power as 4 NSTAR ion engines but provide 3x the thrust.

2. Moving Asteroids for Planetary Defense

The propellantless nature of the plasma magnet drive makes it very suitable for pushing asteroids for planetary defense. Once turned on, the drive provides steady thrust to the asteroid, propelling it away from the sun and raising its orbit. Because the drive does not need to be facing any particular direction, it can be attached to a tumbling asteroid without any impact on the thrust direction.

3. Charged particle radiation shield for crewed flights

The magnetosphere generated by the engine makes a good radiation shield for the charged particles of the solar wind. It should prove to be a good solution for the solar wind, solar flares and even coronal mass ejections (CME). This device could, therefore, be used for human flight to reduce radiation effects. For human crewed flights, the 1N of thrust is insufficient for the size of the spacecraft and would have a marginal propulsion compared to the main engines. Given the plasma magnet’s small size and mass, and relatively low power requirements, the device provides a cost-effective means to protect the crew without resorting to large masses of physical shielding. The plasma magnet would appear to be only effective for the charged solar wind, leaving the neutral GCRs to enter the craft. However, when an auxiliary device is used in the mode of aerobraking, the charge exchange mechanism should reduce the galactic cosmic ray (GCR) penetration (see item 8 below).

4. Asteroid mining

The plasma magnet thruster might be a very useful part of a hybrid solution for automated mining craft. The hybrid propulsion would ally the plasma magnet thruster with a propellant system, such as a chemical or ion engine. The outward bound trip would use the plasma magnet thruster to reach the target asteroid. The propellant tanks would be empty saving mass and therefore improving performance. The propellant tanks would be filled with the appropriate resource, e.g. water for an electrothermal engine, or for a L2/O2 chemical engine. This engine would be turned on for the return trip towards the inner system. The reverse would be used for outward bound trips to the inner system

5. Interstellar precursor using nuclear power

A key feature of the plasma magnet is that the diameter of the magnetosphere increases as the density of the solar wind decreases as it expands away from the sun. The resulting expansion exactly matches the decrease in density, ensuring constant thrust. Therefore the plasma magnet has a constant acceleration irrespective of its position in the solar system.

As the solar wind operates out to the heliopause, about 80 AU from the sun, the acceleration from a nuclear powered craft is constant and the craft continues to accelerate without the tyranny of the rocket equation. Assuming a craft with an all up mass of 1 MT (700 kg nuclear power unit, 10 kg engine, and the remaining in payload), the terminal velocity at the heliopause is 150 km/s. The flight time is 4.75 years, which is a considerably faster flight time than the New Horizons and Voyager probes.

Slough assumed a solar array power supply, functional out to the orbit of Jupiter at 5 AU. This limited the velocity of the drive, although the electrical power output of a solar array at 1 AU is about 10-fold better than a nuclear power source, but rapidly decreases with distance from the sun. Assuming a 10 kW PV array, generating decreasing power out to Jupiter, the final velocity of the 1 MT craft is somewhere between 5 and 10 km/s, but with a much larger payload.

In his TVIW talk [1], Greason suggested that the 10kW power supply could propel a 2500 kg craft with an acceleration of 0.5g, reaching 400-700 km/s in just half a day. Greason [i] suggested that with this acceleration, the FOCAL mission for gravitational lens telescopes requiring many craft should be achievable. *

6. Mars Cycler

Greason suggested that the plasma magnet might well be useful for a Mars cycler, as the small delta v impulse needed for each trip could be easily met.[1]

7. Deceleration at target star for interstellar flight

For interstellar flights, deploying the plasma magnet as the craft approaches the target star should be enough to decelerate the craft to allow loitering in the system, rather than a fast flyby. Again, the high performance and modest mass and power requirements might make this a good way to decelerate a fast interstellar craft, like a laser propelled photon sail.[1]

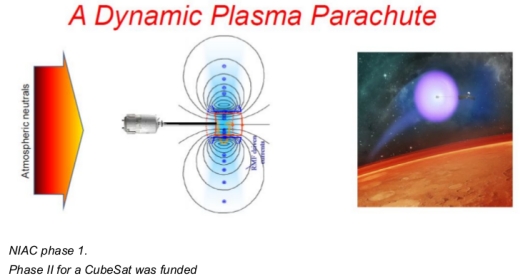

8. Magnetoshell Aerocapture (MAC)

While the studies on the plasma magnet seemed to have stalled by the late 2000s, a very similar technology development was gaining attention. A simple dipole magnet magnetosphere can be used as a very effective aerocapture shield. The shield is just the plasma magnet with coils that do not rotate, creating a magnetosphere of a diameter in meters, one that requires the injection of gram quantities of plasma to be trapped in the magnetic field. As the magnetosphere impacts the atmosphere, the neutral atmosphere molecules are trapped by charge exchange. The stopping power is on the order of kilonewtons, allowing the craft to achieve orbit and even land without a heavy, physical shield. The saving in mass and hence propellant is enormous. Such aerobraking allows larger payloads, or alternatively faster transit times. Because the magnetoshell is immaterial, heat transmission to the shield is not an issue. The mass saving is considerable and offers a very cost-effective approach for any craft to reduce mass, propellant requirements or increase payloads. This approach is suitable for Earth return, Mars, outer planets, and Venus capture. Conceivably aerocapture might be possible with Pluto.

Figure 4. A dipole magnet creating a small diameter magnetic field is injected with plasma. As the magnetosphere impacts the atmosphere, charge exchange result in kilonewton braking forces. The diagram at left shows the craft with the training magnetosphere impacting the atmosphere. The painting on the right shows what such a craft might look like during an aerobraking maneuver. Source: Kirtley et al [3].

Making the plasma magnet thrust directional

A single magnetosphere cannot deflect the solar wind in any significant directional way, which limits this drive’s navigational capability. However, if the magnetosphere could be shaped so that its surface could result in an asymmetric deflection, it should be possible to use the drive for tacking back to the inner system.

Figure 5 shows an array of plasma magnets orientated at an angle to the solar wind. The deflection of the solar wind is no longer symmetric, with the main flow across the forward face of the array. Under those conditions, there should be a net force against the grid. This suggests that like a solar sail, orientating the grid so that the force retards the orbital velocity, the craft should be able to spiral down towards the Sun, offering the possibility of a drive that could navigate the solar system.

Figure 5. A grid of plasma magnets deflects the flow of the solar wind, creating a force with a component that pushes against the grid. If the grid is in orbit with a velocity from right to left, the force will reduce the grid’s velocity and result in a spiral towards the Sun.

Pushing the Boundaries

The size of the magnetic sail can be increased with higher power inputs, or increasing the antenna size. Optimization will depend on the size of the craft and the mass of the antenna. Truly powerful drives can be considered. Greason [12] has calculated that a 2 MT craft, using a superconducting antenna with a radius of 30 meters, fed with a peak current of 90 kA, would have a useful sail with a radius of 1130 km and an acceleration of 2 m/s2, or about 0.2g. As the sail has a maximum velocity of that of the solar wind, a probe accelerating at 0.2g would reach maximum velocity in a few days, and pass by Mars within a week. To reach a velocity of 20 km/s, faster than New Horizons, the Plasma magnet would only need to be turned on for a few hours. Clearly, the scope for using this drive to accelerate probes and even crewed ships is quite exciting.

Coupling a more modest velocity of just 10’s of km/s with the function of a MAC, a craft could reach Mars in less than 2 months and aerobrake to reach orbit and even descend to the surface. All this without propellant and a very modest solar array for a power supply.

An Asteroid, a tether and a Round Trip Flight

As we’ve seen, the plasma magnet can only propel a craft downwind from the Sun. So far I have postulated that aerobraking and conventional drives would be needed for return flights. One outlandish possibility for use in asteroid mining might be the use of a tether to redirect the craft. On the outward bound flight, the craft driven by the plasma magnet makes a rapid approach to the target asteroid which is being mined. The mined resources are attached to a tether that is anchored to the asteroid. As the craft approaches, it captures the end of the tether to acquire the new payload, and is swung around the asteroid. On the opposite side of the asteroid, the tether is released and the craft is now traveling back towards the Sun. No propellant needed, although the tether might cause some consternation as it wraps itself around the asteroid.

Conclusion

The plasma magnet as a propulsion device, and the same hardware applied for aerocapture, would drastically reduce the costs and propellant requirements for a variety of missions. Coupled with another drive such as an ion engine, a craft could reach a target body with an atmosphere and be injected into orbit with almost no propellant mass. The return journey would require an engine delivering just enough delta V to escape that body and return to Earth, where aerocapture again would allow injection into Earth orbit with no extra propellant. If direction deflection can be achieved, then the plasma magnet might be used to navigate the Solar System more like a solar sail, but with a far higher performance, and far easier deployment.

Using a steady, nuclear power or beamed power source, such a craft could accelerate to the heliopause, allowing interstellar precursor missions, such as Kuiper belt exploration and the FOCAL mission within a short time frame.

The technology of the plasma magnet combined with a MAC could be used to decelerate a slowish interstellar ship and allow it to achieve orbit and even land on a promising exoplanet.

The size of the magnetic sail can be extended with few constraints, allowing for considerably increased thrust that can be applied to robotic probes and crewed spacecraft. For crewed craft, the magnetosphere also provides protection from the particle radiation from the sun, and possibly galactic cosmic rays.

Given the potential of this drive and relatively trivial cost, it seems that testing such a device in space should perhaps be attempted. Can a NewSpace billionaire be enticed?

* These numbers are far higher than those provided by Winglee and Slough in their papers and so I have used their much more conservative values for all my calculations.

References

Greason, Jeff “Missions Enabled by plasma magnet Sails”, Presentation at the Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0vVOtrAnIxM

Janhunen, P., The electric sail – a new propulsion method which may enable fast missions to the outer solar system, J. British Interpl. Soc., 61, 8, 322-325, 2008.

Kelly, Charles and Shimazu, Akihisa “Revolutionizing Orbit Insertion with Active Magnetoshell Aerocapture,” University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 98195, USA.

Kirtley, David, Slough, John, and Pancotti, Anthony “Magnetoshells Plasma Aerocapture for Manned Missions and Planetary Deep Space Orbiters”, NIAC Spring Symposium, Chicago, Il., March 12, 2013

Slough, John. “The plasma magnet for Sailing the Solar Wind.” AIP Conference Proceedings, 2005, doi:10.1063/1.1867244.

Slough, John “The plasma magnet” (2006). NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts Phase 1 Final Report.

Winglee, Robert. “Mini-Magnetospheric Plasma Propulsion (M2P2): High Speed Propulsion Sailing the Solar Wind.” AIP Conference Proceedings, 2000, doi:10.1063/1.1290892.

Winglee, R. M., et al. “Mini-Magnetospheric Plasma Propulsion: Tapping the Energy of the Solar Wind for Spacecraft Propulsion.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, vol. 105, no. A9, Jan. 2000, pp. 21067-21077., doi:10.1029/1999ja000334.

Zubrin, Robert, and Dana Andrews. “Magnetic Sails and Interplanetary Travel.” 25th Joint Propulsion Conference, Dec. 1989, doi:10.2514/6.1989-2441.

Greason, Jeff. Personal communication.

by Paul Gilster | Jan 20, 2017 | Autonomy and Robotics |

Early probes are one thing, but can we build a continuing presence among the stars, human or robotic? An evolutionary treatment of starflight sees it growing from a steadily expanding presence right here in our Solar System, the kind of infrastructure Alex Tolley examines in the essay below. How we get to a system-wide infrastructure is the challenge, one analyzed by a paper that sees artificial intelligence and 3D printing as key drivers leading to a rapidly expanding space economy. The subject is a natural for Tolley, who is co-author (with Brian McConnell) of A Design for a Reusable Water-Based Spacecraft Known as the Spacecoach (Springer, 2016). An ingenious solution to cheap transportation among the planets, the Spacecoach could readily be part of the equation as we bring assets available off-planet into our economy and deploy them for even deeper explorations. Alex is a lecturer in biology at the University of California, and has been a Centauri Dreams regular for as long as I can remember, one whose insights are often a touchstone for my own thinking.

by Alex Tolley

Crewed starflight is going to be expensive, really expensive. All the various proposed methods from slow world ships to faster fusion vessels require huge resources to build and fuel. Even at Apollo levels of funding in the 1960’s, an economy growing at a fast clip of 3% per year is estimated to need about half a millennium of sustained growth to afford the first flights to the stars. It is unlikely that planet Earth can sustain such a sizable economy that is millions of times larger than today’s. The energy use alone would be impossible to manage. The implication is that such a large economy will likely be solar system wide, exploiting the material and energy resources of the system with extensive industrialization.

Economies grow by both productivity improvements and population increases. We are fairly confident that Earth is likely nearing its carrying capacity and certainly cannot increase its population even 10-fold. This implies that such a solar system wide economy will need huge human populations living in space. The vision has been illustrated by countless SciFi stories and perhaps popularized by Gerry O’Neill who suggested that space colonies were the natural home of a space faring species. John Lewis showed that the solar system has immense resources to exploit that could sustain human populations in the trillions.

Image credit: John Frassanito & Associates

But now we run into a problem. Even with the most optimistic estimates of reduced launch costs, and assuming people want to go and live off planet probably permanently, the difficulties and resources needed to develop this economy will make the US colonization by Europeans seem like a walk in the park by comparison. No doubt it can be done, but our industrial civilization is little more than a quarter of a millennium old. Can we sustain the sort of growth we have had on Earth for another 500 years, especially when it means leaving behind our home world to achieve it? Does this mean that our hopes of vastly larger economies, richer lives for our descendents and an interstellar future for humans is just a pipe dream, or at best a slow grind that might get us there if we are lucky?

Well, there may be another path to that future. Philip Metzger and colleagues have suggested that such a large economy can be developed. More extraordinary, that such an economy can be built quickly and without huge Earth spending, starting and quickly ending with very modest space launched resources. Their suggestion is that the technologies of AI and 3D printing will drive a robotic economy that will bootstrap itself quickly to industrialize the solar system. Quickly means that in a few decades, the total mass of space industrial assets will be in the millions of tonnes and expanding at rates far in excess of our Earth-based economies.

The authors ask, can we solve the launch cost problem by using mostly self-replicating machines instead? This should remind you of the von Neumann replicating probe concept. Their idea is to launch seed factories of almost self-replicating robots to the Moon. The initial payload is a mere 8 tonnes. The robots will not need to be fully autonomous at this stage as they can be teleoperated from Earth due to the short 2.5 second communication delay. They are not fully self-replicating at this stage as need for microelectronics is best met with shipments from Earth. Almost complete self-replication has already been demonstrated with fabs, and 3D printing promises to extend the power of this approach.

The authors assume that initial replication will neither be fully complete, nor high fidelity. They foresee the need for Earth to ship the microelectronics to the Moon as the task of building fabs is too difficult. In addition, the materials for new robots will be much cruder than the technology earth can currently deliver, so that the next few generations of robots and machinery will be of poorer technology than the initial generation. However the quality of replication will improve with each generation and by generation 4, a mere 8 years after starting, the robot technology will be at the initial level of quality, and the industrial base on the Moon should be large enough to support microelectronics fabs. From then on, replication closure is complete and Earth need ship no further resources to the Moon.

| Gen | Human/Robotic Interaction | Artificial Intelligence | Scale of Industry | Materials Manufactured | Source of Electronics |

| 1.0 | Teleoperated and/or locally operated by a human outpost | Insect-like | Imported, small-scale, limited diversity | Gases, water, crude alloys, ceramics, solar cells | Import fully integrated machines |

| 2.0 | Teleoperated | Lizard-like | Crude fabrication, inefficient, but greater throughput than 1.0 | (Same) | Import electronics boxes |

| 2.5 | Teleoperated | Lizard-like | Diversifying processes, especially volatiles and metals | Plastics, rubbers, some chemicals | Fabricate crude components plus import electronics boxes |

| 3.0 | Teleoperated with experiments in autonomy | Lizard-like | Larger, more complex processing plants | Diversify chemicals, simple fabrics, eventually polymers | Locally build PC cards, chassis and simple components, but import the chips |

| 4.0 | Closely supervised autonomy | Mouse-like | Large plants for chemicals, fabrics, metals | Sandwiched and other advanced material processes | Building larger assets such as lithography machines |

| 5.0 | Loosely supervised autonomy | Mouse-like | Labs and factories for electronics and robotics. Shipyards to support main belt. | Large scale production | Make chips locally. Make bots in situ for export to asteroid belt. |

| 6.0 | Nearly full autonomy | Monkey-like | Large-scale, self-supporting industry, exporting industry to asteroid main belt | Makes all necessary materials, increasing sophistication | Makes everything locally, increasing sophistication |

| X.0 | Autonomous robotics pervasive throughout Solar System enabling human presence | Human-like | Robust exports/imports through zones of solar system | Material factories specialized by zone of the Solar System | Electronics factories in various locations |

Table 1. The development path for robotic space industrialization. The type of robots and the products created are shown. Each generation takes about 2 years to complete. Within a decade, chip fabrication is initiated. By generation 6, full autonomy is achieved.

| Asset | Qty. per set | Mass minus Electronics (kg) | Mass of Electronics (kg) | Power (kW) | Feedstock Input (kg'hr) | Product Output (kg/hr) |

| Power Distrib & Backup | 1 | 2000 | ----- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Excavators (swarming) | 5 | 70 | 19 | 0.30 | 20 | ---- |

| Chem Plant 1 - Gases | 1 | 733 | 30 | 5.58 | 4 | 1.8 |

| Chem Plant 2 - Solids | 1 | 733 | 30 | 5.58 | 10 | 1.0 |

| Metals Refinery | 1 | 1019 | 19 | 10.00 | 20 | 3.15 |

| Solar Cell Manufacturer | 1 | 169 | 19 | 0.50 | 0.3 | ---- |

| 3D Printer 1 - Small Parts | 4 | 169 | 19 | 5.00 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 3D Printer 2 - Large Parts | 4 | 300 | 19 | 5.00 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Robonaut assemblers | 3 | 135 | 15 | 0.40 | ---- | ---- |

| Total per Set | ~7.7 MT

launched to Moon | 64.36 kW | 20 kg

regolith/hr | 4 kg

parts/hr |

Table 2. The products and resources needed to bootstrap the industrialization of the Moon with robots. Note the low mass needed to start, a capability already achievable with existing technology. For context, the Apollo Lunar Module had a gross mass of over 15 tonnes on landing.

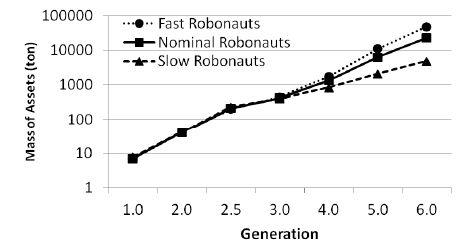

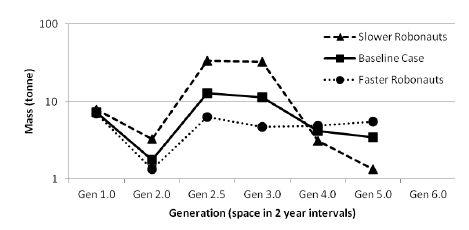

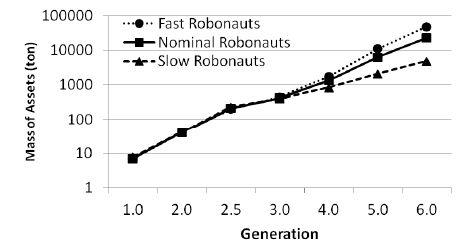

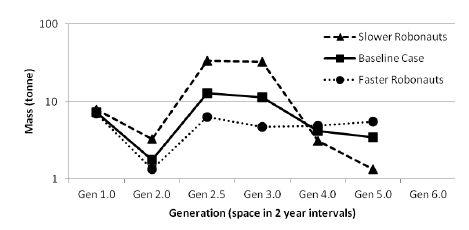

The authors test their basic model with a number of assumptions. However the conclusions seem robust. Assets double every year, more than an order of magnitude faster than Earth economic growth.

Figure 13 of the Metzger paper shows that within 6 generations, about 12 years, the industrial base off planet could potentially be pushing towards 100K MT.

Figure 14 of the paper shows that with various scenarios for robots, the needed launch masses from Earth every 2 years is far less than 100 tonnes and possibly below 10 tonnes. This is quite low and well within the launch capabilities of either government or private industry.

Once robots become sophisticated enough, with sufficient AI and full self-replication, they can leave the Moon and start industrializing the asteroid belt. This could happen a decade after initiation of the project.

With the huge resources that we know to exist, robot industrialization would rapidly, within decades not centuries, create more manufactures by many orders of magnitude than Earth has. Putting this growth in context, after just 50 years of such growth, the assets in space would require 1% of the mass of the asteroid belt, with complete use within the following decade. Most importantly, those manufactures, outside of Earth’s gravity well, require no further costly launches to transmute into useful products in space. O’Neill colonies popped out like automobiles? Trivial. The authors suggest that one piece could be the manufacture of solar power satellites able to supply Earth with cheap, non-polluting power, in quantities suitable for environmental remediation and achieving a high standard of living for Earth’s population.

With such growth, seed factories travel to the stars and continue their operation there, just as von Neumann would predict with his self-replicating probes. Following behind will be humans in starships, with habitats already prepared by their robot emissaries. All this within a century, possibly within the lifetime of a Centauri Dreams reader today.

Is it viable? The authors believe the technology is available today. The use of telerobotics staves off autonomous robots for a decade. In the 4 years since the article was written, AI research has shown remarkable capabilities that might well increase the viability of this aspect of the project. It will certainly need to be ready once the robots leave the Moon to start extracting resources in the asteroid belt and beyond.

The vision of machines doing the work is probably comfortable. It is the fast exponential growth that is perhaps new. From a small factory launched from Earth, we end up with robots exploiting resources that dwarf the current human economy within a lifetime of the reader.

The logic of the model implies something the authors do not explore. Large human populations in space to use the industrial output of the robots in situ will need to be launched from Earth initially. This will remain expensive unless we are envisaging the birthing of humans in space, much as conceived for some approaches to colonizing the stars. Alternatively an emigrant population will need to be highly reproductive to fill the cities the robots have built. How long will that take? Probably far longer, centuries, rather than the decades of robotic expansion.

Another issue is that the authors envisage the robots migrating to the stars and continuing their industrialization there. Will humans have the technology to follow, and if so, will they continue to fall behind the rate at which robots expand? Will the local star systems be full of machines, industriously creating manufactures with only themselves to use them? And what of the development of AI towards AGI, or Artificial General Intelligence? Will that mean that our robots become the inevitable dominant form of agency in the galaxy?

The paper is Metzger, Muscatello, Mueller & Mantovani, “Affordable, Rapid Bootstrapping of the Space Industry and Solar System Civilization,” Journal of Aerospace Engineering Volume 26 Issue 1 (January 2013). Abstract / Preprint.

by Paul Gilster | Aug 17, 2016 | Asteroid and Comet Deflection |

Most readers will recall the Spacecoach, developed by Brian McConnell and Alex Tolley and widely discussed in these pages. A workhorse spacecraft designed to shuttle crew and cargo between Earth and nearby planets, the Spacecoach was presented as a way to open up regular commercial use of the Solar System, on the pattern of the stagecoaches that connected towns in the American Old West. One of the many beauties of the Spacecoach was the idea of using reclaimed water and waste gases as a propellant in its electric engines.

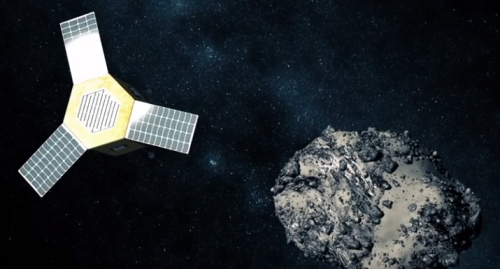

With water as a propellant, the mass of the system can be sharply reduced, with an associated reduction in mission costs. Benefits like that don’t stay hidden for long, and I see that Deep Space Industries is likewise attracted to water in the design of its new engine. The Prospector-1 spacecraft, slated for launch by the end of the decade, uses a system DSI calls ‘Comet.’ It expels superheated water to create thrust, a useful idea given the company’s intentions.

“During the next decade, we will begin the harvest of space resources from asteroids,” said Daniel Faber, CEO at Deep Space Industries. “We are changing the paradigm of business operations in space, from one where our customers carry everything with them, to one in which the supplies they need are waiting for them when they get there.”

And as Faber’s news release is quick to point out, water will be early on the list of asteroid mining products, meaning that the company realizes the importance of refueling in space. Prospector-1 is being developed as the world’s first commercial interplanetary mining mission, designed to rendezvous with a near-Earth asteroid and evaluate its potential for mining operations. The plan is to key off the earlier Prospector-X mission, which will test DSI technologies in low-Earth orbit as a precursor to the more ambitious Prospector-1.

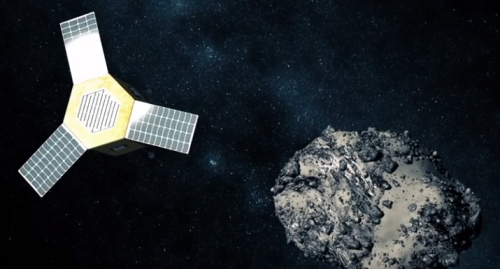

Image: Artist’s conception of Prospector-1, Deep Space Industries’ planned commercial mining mission, approaching a near-Earth asteroid. Credit: DSI.

We’ve had good views of asteroids from a number of missions now, including Galileo, Hayabusa, which landed on the asteroid Itokawa and returned samples to Earth, NEAR-Shoemaker, Deep Space 1 and, of course, Dawn, which continues to provide us with high quality data from Ceres after its long period of operations at Vesta. The list could be extended, for as you can see above, many missions, like Galileo and Cassini, imaged asteroids on their way to their final destinations. It was Jupiter-bound Galileo that discovered that the asteroid Ida had a small satellite (Dactyl). Galileo also imaged the asteroid Gaspra.

Prospector-1’s asteroid is to be chosen from the host of near-Earth asteroids, with mapping operations of its surface and subsurface, visual and infrared imaging and analysis of water content down to a depth of one meter. After the initial science campaign, Prospector-1 will use its water thrusters to make a touchdown on the asteroid for further analysis. “The ability to locate, travel to, and analyze potentially rich supplies of space resources is critical to our plans,” continued Faber. “This means not just looking at the target, but actually making contact.”

In Living Off the Land in Space (Copernicus, 2007), Gregory Matloff, Les Johnson and C Bangs looked at asteroid mining as one possibility in a program of long-term human migration off our planet. The authors drew particular attention to the asteroid 2001 CQ36, a near-Earth object with a diameter estimated to be between 90 and 300 meters. 2001 CQ36 might be an excellent asteroid for an early look by a space mining company, given not only its resource potential but the fact that it is on an orbit that could potentially cause problems.

The asteroid approaches the Earth in 2021, 2022, 2031 and 2033, with the 2031 pass closing to 0.02 AU. Assuming a diameter of 150 meters, Matloff, Johnson and Bangs work out an estimated mass of 3 billion kilograms (this also assumes a spherical shape and a specific gravity intermediate between water and rock). 2001 CQ36 is not the sort of thing we want to see impact the Earth, which makes close study of its composition a long-term insurance policy, just in case we ever have to consider nudging an asteroid like this onto a new trajectory.

From the mining perspective, get just a third of the resources available at 2001 CQ36 and you’ve got a billion kilograms of material for space manufacturing. So doubling up on our objectives would seem to make sense when we have objects that can be studied and exploited from both perspectives. Prospector-1 is small (50 kg when fueled) and low cost, intended as a platform for early asteroid mining studies and other forms of inner system exploration. We’ll track its fortunes closely.

by Paul Gilster | Oct 9, 2015 | Astrobiology and SETI |

We often conceive of SETI scenarios in which Earth scientists pick up a beacon-like signal from another star, obviously intended to arouse our attention and provide information. But numerous other possibilities exist. Might we, for example, pick up signs of another civilization’s activities, perhaps through intercepting electromagnetic traffic, or their equivalent of planetary radars? Even more interesting, as Brian McConnell speculates below, is the idea of listening in on a galactic network that contains information not just from one civilization but many. As Centauri Dreams readers know, McConnell and Alex Tolley have been developing the ‘spacecoach’ concept of interplanetary travel, discussed in the just published A Design for a Reusable Water-Based Spacecraft Known as the Spacecoach (Springer, 2015). It’s a shrewd and workable way to get us deep into the Solar System. Today McConnell turns his attention to a SETI network whose detection could offer a big payoff for a young civilization.

by Brian McConnell

With the revival of SETI funding, it’s interesting to contemplate what we might find if SETI succeeds. One possibility that is especially tantalizing is that first contact would not be with an individual civilization but rather a large scale network of civilizations that is organized not unlike the Internet. This is not a new idea (Timothy Ferris and others have explored this concept) but it is one that should be considered seriously. Assuming that communicative civilizations are commonplace, a big if of course, a decentralized or mesh network will be the most time and energy efficient way for them to organize their communications.

Consider the energy cost of sending a unit of information from one edge of the galaxy to the other (~ 100,000 light years) via direct means versus a peer-to-peer relay system. The savings ratio can be estimated as:

daverage / wgalaxy

If communicative civilizations are separated by an average distance of, say, 1000 light years, the energy cost of sending a unit of information across the galaxy via relay will be about 1/100th that of direct communication. The energy requirement per link drops off by the ratio of (daverage / wgalaxy)2 but as more hops are required with shorter links, the overall energy requirement drops by daverage / wgalaxy. This is an approximation, but it highlights the order of magnitude improvements in economy, and suggests that if communicative civilizations are widespread, energy economics and other considerations will favor this type of arrangement.

Reliability and redundancy are another important feature of a mesh network. When sending information across such great distances, and with such long transit times, a sender may want to protect especially important information against loss or corruption by sending it repeatedly or by sending it via multiple paths between endpoints. This technique can virtually guarantee that information is eventually transmitted even if the network is damaged, even without the use of sophisticated forward error correction codes. This isn’t to say that an extraterrestrial intelligence will copy the TCP/IP protocol, but it’s safe to assume that someone who is sophisticated enough to build an interstellar communication link will probably be familiar with the characteristics and benefits of decentralized mesh networks.

There will also be benefits to receivers, especially newcomers, as contact with one node will be the same as contacting many nodes, since any node in the network can function as a relay for others. The cost of joining the network is also reduced, as a new node need only establish communication with its nearest neighbors, and can relay messages to and receive information from any other site on the network. Such a network would not merely be a communication system, but also a long term repository of knowledge as important information from long dead civilizations could continue to circulate throughout the network in perpetuity.

Image: The Milky Way as seen from the mountains of West Virginia. Could the galaxy be filled with the traffic of networked civilizations? Credit: ForestWander.

Fermi Implications

The existence of such a system might also help explain the Fermi Paradox, as the most energy efficient mode of operation, in terms of detecting new civilizations, will be for each node to concentrate its detection efforts on its immediate neighborhood using a listen and reply strategy. There would be little point in building powerful omnidirectional beacons that are detectable over great distances, as they would cost far more energy to operate, would have to wait millennia for a response, and would be plagued by duty cycle issues. Better for peripheral nodes to listen for microwave leakage from nearby civilizations as they develop early communication technology, and then target those for active communication soon after they are detected. This sort of strategy would be cheap both in terms of energy and the number of radio-telescopes required at each node in the network, and would offer a high probability of success in detecting new nodes just as they become active, while not wasting energy by transmitting in the blind.

An important point to consider here is that an emerging technological civilization would become detectable independently of any intent to attempt interstellar communication. Indeed here on Earth, the vast vast majority of energy expended on electromagnetic signaling has been for purposes other than Active SETI. It seems likely that most technological civilizations would go through a period where they are microwave bright, even if they later go dark due to transitioning to other technology, fear of ETI contact, etc.

As we would just now be detectable to nodes within about 100LY (80LY is probably a better estimate), we would just now expect to be receiving a response from a node within 40-50LY. It’s possible that rapid changes in atmospheric spectra, as Earth has experienced with the sudden increase in carbon dioxide, might also serve as a early tripwire for attempting active communication, but those could be ambiguous signals with natural explanations like volcanism, whereas a sudden spike in monochromatic microwave transmission points definitively to a technological origin. Viewed from the network’s perspective, this decentralized strategy would enable detection of new sites with the least energy expenditure and the shortest possible lag time between detection and active communication, with the added bonus feature that the first nodes to establish contact could relay stored information from nodes far beyond the initial radius of communication. On the other hand, if the average distance between nodes is large, it may be a long time before the nearest nodes are aware of us, and it may be hard for such a network to become established in the first place.

Choice of Encoding Schemes

Another interesting aspect of a long running galactic communication system is that there will be a natural selection of sorts that favors the message encoding schemes that are most likely to be mimicked. The selection pressure in this case will favor an encoding scheme that is broadly comprehensible (easy to understand the basic design pattern) and flexible (able to accommodate many different types of information via that framework). A transmission that is extremely difficult to parse, for example because of strong encryption or sophisticated forward error correction codes, is less likely to be mimicked than one whose basic design pattern is comprehensible to many receivers, even if it is less than optimal in terms of capacity or error resistance. This leads to the fittest message being more likely to replicate (be mimicked in retransmission) than its competitors. This is also an incentive for civilizations wishing to project influence through remote communication to design messages that peer sites will want to and be able to copy.

The point is not to speculate about what would be in such a message, but how it is organized at a low level. To build a mesh network that can handle many data types, you don’t need a very sophisticated message format, even if some of the data types sent within the message are extremely complex or difficult to comprehend. Typically you break a large amount of data, be it a file or communication stream, into smaller predictably organized subunits which are labeled with metadata, which might include:

- a frame or packet number : identifies a message segment’s position within a collection, file, stream, etc

- a collection or file number : to identify a larger grouping of frames, pages, packets, etc

- an author or sender number : to identify the author or sender of a particular segment.

- a receiver number : to identify the intended recipient, if any

- a content identifier : to identify the type of content represented by the frame or packet

- a blob of data, or payload, that is described by the above metadata

While one could design more complex schemes, the above defines the minimal set of metadata needed to describe something like a mesh network or file system with many files, authors and varying file types. What someone decides to convey with such a system is a different matter entirely, but a mesh network in its simplest form consists of a long chain of | meta data | blob of data | meta data | blob of data | segments with obvious repeating structures.

Implications for SETI

While the basic design pattern of a system like this can be rather simple, it will be capable of delivering data that varies widely in content type and “difficulty level”, and also offers a high degree of durability (important message fragments can be resent out of sequence or sent via multiple paths). Some content types such as rasterized or bitmapped images will probably be nearly universally understood due to their utility in astronomy and space photography, while others that are based on advanced math may be unrecognizable to many recipients. It’s not unlike DNA, whose basic encoding scheme has just four letters, yet can encode for something as simple as an isolated protein or as complex as a human being. That’s one of the interesting characteristics of the fittest message — it should be easy to parse at a low level, yet capable of conveying data types representing a wide range of complexity.

All of this suggests that SETI surveys should be concentrating a portion of their observing time on nearby targets. This also suggests that a large scale network will probably need to find us before we can find it, but will also be relatively easy to spot once it does. This doesn’t exclude other possibilities, and indeed SETI should be trying many strategies in parallel, from looking for distant beacons to Bracewell probes.

Should we encounter a network like this, the implications of that would be nothing short of staggering because of the volume and variety of information that could flow through a system like this. It’s possible that much of that communication will be over our heads. On the other hand, the quasi Darwinian selection pressure on message formats may favor those that are broadly comprehensible, or at least contain elements like rasterized photos that virtually any astronomically communicative receiver can understand, including us.