Early next week I’ll be discussing the winning entry in Project Hyperion’s design contest to build a generation ship. But I want to sneak in the just announced planet candidate at Alpha Centauri A today, a good fit with the Hyperion work given that the winning entry at Hyperion is designed around a crewed expedition to nearby Proxima Centauri. Any news we get about this triple star system rises immediately to the top, given that it’s almost certainly going to be the first destination to which we dispatch instrumented unmanned probes.

And one day, perhaps, manned ships, if designs like Hyperion’s ‘Chrysalis’ come to fruition. More on that soon, but for today, be aware that the James Webb Space Telescope is now giving us evidence for a gas giant orbiting Centauri A, the G-class star intriguingly similar to the Sun, which is part of the close binary that includes Centauri B, both orbited by the far more distant Proxima.

Image: This artist’s concept shows what the gas giant orbiting Alpha Centauri A could look like. Observations of the triple star system Alpha Centauri using the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope indicate the potential gas giant, about the mass of Saturn, orbiting the star by about two times the distance between the Sun and Earth. In this concept, Alpha Centauri A is depicted at the upper left of the planet, while the other Sun-like star in the system, Alpha Centauri B, is at the upper right. Our Sun is shown as a small dot of light between those two stars. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, R. Hurt (Caltech/IPAC).

JWST’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) once again proves its worth, as revealed in two papers in process at The Astrophysical Journal Letters. If this can be confirmed as a planet, its orbit appears to be eccentric (e ≈ 0.4) and significantly inclined with respect to the orbital plane of Centauri A and B. But we have a lot of work ahead to turn this candidate, considered ‘robust’ by the team working on it, into a solid detection.

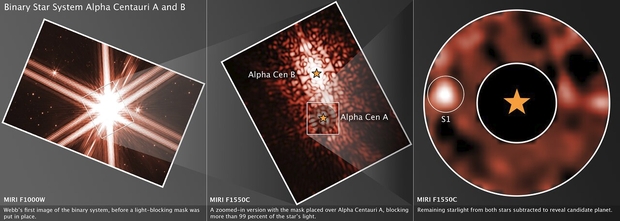

The proximity of the central binary stars at Alpha Centauri makes this kind of work extremely difficult, one reason why a system so close to our own is only gradually revealing its secrets. Bear in mind that MIRI was able to subtract the light from both stars to reveal an object 10,00 times fainter than Centauri A. The Webb instrument took observations beginning in August of 2024 that posed a subsequent problem, for two additional observation periods in the spring of this year failed to find the object. Interestingly, computer simulations have clarified what may have happened, according to PhD student Aniket Sanghi (Caltech), co-first author of one of the two papers describing this work:

“We are faced with the case of a disappearing planet! To investigate this mystery, we used computer models to simulate millions of potential orbits, incorporating the knowledge gained when we saw the planet, as well as when we did not,.. We found that in half of the possible orbits simulated, the planet moved too close to the star and wouldn’t have been visible to Webb in both February and April 2025.”

Image: This 3-panel image captures the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope’s observational search for a planet around the nearest Sun-like star, Alpha Centauri A. The initial image shows the bright glare of Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B, then the middle panel shows the system with a coronagraphic mask placed over Alpha Centauri A to block its bright glare. However, the way the light bends around the edges of the coronagraph creates ripples of light in the surrounding space. The telescope’s optics (its mirrors and support structures) cause some light to interfere with itself, producing circular and spoke-like patterns. These complex light patterns, along with light from the nearby Alpha Centauri B, make it incredibly difficult to spot faint planets. In the panel at the right, astronomers have subtracted the known patterns (using reference images and algorithms) to clean up the image and reveal faint sources like the candidate planet. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, DSS, A. Sanghi (Caltech), C. Beichman (JPL), D. Mawet (Caltech), J. DePasquale (STScI).

The combination of observations and orbital simulations indicates that a gas giant of about Saturn mass moving in an elliptical orbit within Centauri A’s habitable zone remains a viable option. Also fed into the mix were the parameters of a 2019 observation of Centauri A and B from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope. It is clear that the point source referred to as S1 is not a background object like a galaxy or a foreground asteroid moving between JWST and the star. Its orbital parameters would make it quite interesting given the tight separation between Centauri A and B.

The second of the two papers clarifies the significance of such a find and the need to confirm it. The temperature calculated below is based on the photometry and orbital properties of the candidate object, with 200–350 K originally expected for a planet heated by Centauri A at 1.3 AU:

A confirmation of the S1 candidate as a gas giant planet orbiting our closest solar-type star,α Cen A, would present an exciting new opportunity for exoplanet research. Such an object would be the nearest (1.33 pc), coldest (∼225 K), oldest (∼5 Gyr), shortest period (∼2–3 years), and lowest mass (≲ 200 M⊕) planet imaged in orbit around a solar-type star, to date. Its extremely cold temperature would make it more analogous to our own gas giant planets and an important target for atmospheric characterization studies. Its very existence would challenge our understanding of the formation and subsequent dynamical evolution of planets in complex hierarchical systems. Future observations will confirm or reject its existence and then refine its mass and orbital properties, while multi-filter photometric and, eventually, spectroscopic observations will probe its physical nature.

The papers are Beichman et al., “Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits,” accepted at Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint); and Sanghi, et al., “Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. II. Binary Star Modeling, Planet and Exozodi Search, and Sensitivity Analysis,” accepted at ApJL (preprint). The paper on the 2019 observation is Wagner at al., “Imaging low-mass planets within the habitable zone of α Centauri,” Nature Communications 10 February 2021 (full text).

So now we have two telescopic observations of candidate planets – a smaller one observed by VLT at 1.1 AU, and a larger one by the JWST at 2 AU.

So why did the VLT not see the larger JWST candidate? And why did JWST miss the VLT candidate across all three observations?

Great and exciting news! Especially for this forum so-named and devoted.

As close a call as this one is, I think it worth raising a glass for a toast.

Initial reports suggest or indicate considerable inclination to Alpha Centauri A-B plane. It would certainly be interesting to know how much. Circular orbit at 2 AU would be roughly 2 years or more, but if the observation is at apastron, then the period would be reduced accordingly.

Studies of terrestrial planets in the stellar binary plane indicate that the variations in eccentricity and elliptical orientation would be of higher amplitude and shorter period than those experienced by Earth and Mars influenced largely by Jupiter. Considering Alpha Centauri B as the corresponding source of perturbation, it’s four or five times further away most of the time but about 800 times more massive. Since it is unreasonable to anticipate stable orbits in the Centauri system in plane well into the corresponding solar Asteroid Belt, I’d wager that this planet, if extant, is observed near its apastron. And perhaps near the peak eccentricity of what might be described as its corresponding Milankovitch cycle.

An orbital period for this object will be difficult to extract. Odds are against right away. But dynamics would suggest that it is now at an apastron ( rA) peak. The reach out in AUs cannot be much longer before Alpha Cen B influence would

create chaotic motion and escape. This might even be optimal seeing conditions

right now before the planet recedes into lower radius &/ apastron, increasing glare.

If all of this holds up, then what are prospects for exoplanets in the Alpha Centauri A – B plane? Or perhaps does this planet as understood identify the Alpha Cen original ecliptic plane? And does the stellar primary have a rotational axis in accord with this observation?

Not mentioning satellites, this is getting complicated fast.

Is the system of sufficient interest to warrant a BIG mission? It’d have to be a 250+ year project and we shouldn’t have the mantra of “but we will have something better soon…”. What do we have now and how quickly can we build and launch it??? Just to expand, the mission should hopefully be a generational ship w/o people and with multiple objectives – proxima, A and B (sub)visitors and a primary destination and focus with multiple assets to be deployed there….

@Tesh

We have zero technology to reach Alpha Cen is less than 10s of millennia, let alone a generation ship. This century, we may be able to launch beamed sails with instruments to reach it a lifetime or so. Generation ship technology is out of the question.

The speculative design for the Project Hyperion generation ship is going to be posted next, which hopefully will give you an idea of the scale and technology needed. I am not sure why anyone would want to go unless there is near certainty of a habitable world at teh the target.

Back when interstellar starships were being thought of, the sheer scale of the endeavor required a national or global GDP at least several hundred years of growth to reach a level that would make this affordable. Star Trek: TOS (“Space Seed”), may have had Khan Noonian Singh leave Earth with fellow augmented humans in an STL cryo ship in 1999 to be discovered in space in the 23rd century, but clearly we cannot do that.

The most realistic way to do this, I think, would be with a fission fragment rocket. Assuming an engine that can efficiently fission its fuel such that most fission fragments can be exhausted out the back with their original velocity (3-5% of c), and given a craft with a large fuel/payload mass ratio, i.e. made >99% out of fuel (urainium or plutonium), we could probably reach Alpha Centauri in 50-100 years, including deceleration.

However, there is currently no practical design of such an efficient engine. High efficiency means 1) most fuel is actually fissioned, and 2) most fragments are actually exhausted out the back before they collide with anything else. On top of that, thrust (i.e. throughput) must be high enough to reach cruise speed before arrival.

That’s a VERY high bar.

Come to think of it, a fission fragment engine does not necessarily have to eject fragments directly. The heat from a nuclear reactor could be converted to electricity, which could be used to accelerate the fission fragments (from the spent fuel) out the back. All non-fissioned fuel must be recovered and fed back into the fuel supply. Also difficult, but potentially easier than direct fragment ejection. 50% thermal to electric power conversion is feasible, and an accelerator could also be quite efficient.

I would have thought that the energy and kit to accelerate heavy ions to fractional c would be very high. We cannot do it with ion engines, which can only manage 10s of km/s, nowhere near the 1000s of km/s of an FF rocket. At the extreme, we are talking about small “atom smashers”. It seems to me that the sail concept of emitting fission fragments might be a better way to harness the Ve of fission fragment emission, but even this only seems to reach 150 km/s, 0.005c. TFINER.

Even with Ve of 0.05c, the rocket equation still operates. With Ve = 0.05c, to reach 0.2c requires a mass ratio of 54. For a Ve = 0.03c, the mass ratio = 786.

In both cases, after acceleration to cruise, you need to slow down at the destination.

If the ship or probe can cruise at its Ve, and then decelerate so that the journey to Alpha Centauri takes 100+/- years, then the mass ratio falls to about 7.5, although this assumes that all the payload must be decelerated, which is not required. At least multiple stages are not needed. But we are stuck with no possible operating FF rocket engine in the very near future.

Particle accelerators can accelerate ions to much higher speeds than needed. I don’t know if it can be done at the efficiency and throughput needed, but it seems at least plausible.

Since the fuel is solid, large mass ratios can be achieved by stacking solid blocks of propellant. Total mass is limited by the thrust of the engine. We need enough thrust to accelerate to full speed before we’re halfway there. That could be very difficult, but can be helped by adding extra engines that are later tossed.

I am aware of the fission sail, but it has many inefficiencies and unrecoverable flaws leading to the limitations you mention.

The nuclear electric approach demands high efficiency for 1) heat to electric, 2) ion acceleration, and 3) recovery of unburnt fuel. 1) is solved, at around 50%. 2) and 3) less so, but they might be solvable.

Just wondering if the fission fragment design with a neutron source acting from the side would do. If the fission material was on a disc and we sent neutrons at a shallow angle the chance of fission is much higher because it sees more fission material. We then have powerfull magnetic fields either side to bend and direct the fragments out the back for thrust.

The problem with that is that any consumables that go into the neutron source would have to be carried in addition to the fission fuel. Depending on the fraction of neutrons that actually lead to fission, it is hard to imagine a scenario where the neutron source consumable does not overwhelm the fission fuel in the mass fraction calculation.

We need an engine where the ONLY consumable is the fission fuel and the ONLY exhaust is the fission products. The cruise velocity depends linearly on the overall efficiency and logarithmically on the mass fraction. 0.1c is a super ambitious goal that will require 20-50% efficiency and a very high mass ratio, as Alex has calculated.

Efficiency means the fraction of the energy liberated during fission that is imparted on the exhaust. Times the fraction of fuel that is actually fissioned.

That may be possible with a firstlight fusion drive where fissile material is used instead and imploded at high velocities, near 500 to 1000km/s. Even partial fission would yield good results, I have tried to contact them about it but to no avail.

https://firstlightfusion.com/

Because of the issue of neutron source consumables, a reactor is likely the only way that works, where the fission is its own neutron source. It is very hard to design a reactor that can directionally exhaust a large fraction of fission fragments before they thermalize. The best I’ve seen is one where the fuel is a dust cloud.

The nuclear electric approach gets around that problem, but has its own difficulties.

I read both papers, and if the orbit and eccentricity of this Saturn sized planet is accurate, this is bad news. This planet will have cleared out any existing terrestrial planets from the HZ of Alpha Centauri A.

It won’t have “habitable moons” unless it captures an already existing terrestrial planet. Otherwise, the moons will be small and rocky core remnants of icy moons (see Robin Canup’s work) and probably airless.

If the eccentricity is smaller and the distance from A is 2-3AU, planets in the HZ might have a chance.

The object, if in it’s predicted orbit, should be visible this month (or next)

How many planets have been discovered around binary star systems similar in size to Alpha Centauri A-B? Over the 5.26 billion-year history of such systems, any small Earth-sized planets that may have existed could have become trapped in orbit around the larger gas giant. This situation presents a three-body problem; the interactions with passing stars could lead to unique outcomes.

I am disappointed with the JWST’s coronagraph with the light interference. A new one needs to be built without that problem. It reminds me of what happens when one enlarges a digital photograph of low resolution. There is distortion and one can imagine what one wants in it like planets in it. On the other hand, a gas giant could exist near a star in double star system like Alpha Centauri. The planet just grew with the gas which is limited near to the star. It is still far from five sigma though. I remain critical of fast conclusions and assumptions and news makers without a lot of evidence.

Re: being disappointed with the JWST’s coronagraph with the light interference and a suggestion that a new one needs to be built without that problem.

Per Coronagraphic Detection of Exosolar Planets with the James Webb Space Telescope, M. Clampin, M. Rieke, G. Rieke, R. Doyon, J. Krist, and JWST Science Working Group (couldn’t set it up with a link):

“JWST is not primarily designed to conduct coronagraphic observations. It’s [sic] segmented mirror telescope architecture . . . generates considerable additional diffraction structure in the telescope’s point spread function compared to that of a monolithic mirror.”

It’s of course not currently possible to fit a monolithic mirror that is sufficiently large enough for JWST’s main mission within the faring of the available launch vehicles:

“To give Webb the necessary resolution and sensitivity to fulfill [its main] mission, it was equipped with a 6.5m-wide primary mirror. But this reflecting surface, made up of 18 segments, is so big it had to be folded to fit inside the nosecone of the Ariane. . . . . Each of those 18 segments has had their orientation and curvature adjusted by small motors, enabling them to behave as though they’re a single, monolithic surface. ‘We now have achieved what’s called ‘diffraction limited alignment’ of the telescope: The images are focused together as finely as the laws of physics allow,’ said Marshall Perrin who works on Webb at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.”

https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-60771210

I of course defer to someone (a human, not AI) instead versed in cutting-edge telescope design (I’m just an amateur with a couple of reflecting scopes). But it sounds like they engineered the heck out of this thing to perform its primary mission ably, with that primary mission not being using a coronagraph. And that they’re pushing the envelope with post-imaging processing to extract every bit of performance that the engineering – and the physics of light – allow.

It doesn’t sound to me like JWST is flawed, in rough contrast to Hubble initially. Particularly given the compromises that they necessarily had to make to put a mirror of that size where they put it.

The upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, on track to launch next year, is designed with an active coronagraph that should perform hundreds of times better than Webb’s, and has a multi-star mask set specifically to enable imaging of planets like this candidate around Aloha Centauri.

Yep, good point, Anon.

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (RST) is a telescope purpose built more primarily to use a coronagraph as opposed to also some of the other mission objectives of the JWST, with inter alia a smaller and thus monolithic 2.4 (rather than 6.5) meter primary mirror.

JWST is built more also to explore deep, deep space – such as the first galaxies and stars in the universe. So as best as I understand it thus needs to be a big light bucket (well, without actually a bucket the way it’s designed, just that big honkin’ primary mirror) to pull in that by this point in time and location faint light.

RST is at least more specifically inter alia a dedicated exoplanet hunter.

Both scopes can look at the same targets – such as exoplanets – and to one extent or another are intended to look at exoplanets as targets, and with a coronagraph. But they then bring the different strengths and weaknesses of their overall design – as tailored to their respective overall mission objectives – to the table.

As best as I can tell in looking at telescopes as an amateur, individual telescopes necessarily reflect a compromise in regards to what they’re designed primarily and/or overall to do. They all gather light, and to an extent can look at the same targets. But some scopes do some things better than others, and vice-versa as they’re employed to do different tasks.

Such as looking at the light from a possible exoplanet as close as approximately 4 light years away as opposed to light from an early star or galaxy from as much as 13 billion or so years ago.

And they all have to deal with the physics of light as applied to their particular design, such as diffraction when something is in or at the edge of the light path and/or – apparently as to JWST – an overall mirror is segmented.

So, yeah, it will be interesting to see what RST and the other new scopes see when they look for this planet candidate following upon what JWST has observed.

Well, if RST and the others get off the ground. I don’t keep up with all that, but the Wikipedia entry for RST reflects that it was on the proposed budget chopping block as of April 25, 2025.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nancy_Grace_Roman_Space_Telescope#Funding_history_and_status

I’m a fan – a big fan – of human space exploration, but – forced to a choice – I’d rather put telescopes like these out into space than put humans sooner on Mars and again on the Moon.

Particularly given the to an extent still unresolved questions as to how the current human organism fares in those environments for long durations.

No need to figuratively run to get to those destinations – and despite those unresolved questions – if we have to sacrifice science such as this to get there quite so soon.

[And “farings” should be “fairings” in my earlier comment. One of those times I shouldn’t have internally filtered out the spell checker when proofing and editing.]

‘Aloha Centauri’ – I like that… perhaps one day.

IF there really is a gas giant there, it should appear in distortions of the radial velocity and astrometry of the Alpha Centauri A. Let’s see a computer simulation so see if it matches observations.

Hi Paul

This is amazing and exciting news, please keep us all updated and thanks for the links to the papers.

From a lot of past reading about planets around these Stars all models indicated no Gas giant planets but Terrestrial Planets around both Stars would be stable and fine. A ‘Saturn” like gas giant was unexpected for me and I’m sure a lot of other folks too.

I guess the big questions are does this planet have large Moons? Could an inner terrestrial planet be in a stable orbit inside this world?

Thanks Edwin

@Tesh

A generational ship is one that carries passengers for such a long journey that multiple generations of people are born, live their lives, and die on that ship before it reaches it’s destination. I think you mean a ship designed to last, with self repair, for thousands of years. Calling for a generational ship w/o passengers is missing the point. As to the rest of your post, we can’t get there from here. Yet. Especially not with payloads like you envision.

“A generational ship is one that carries passengers for such a long journey that multiple generations of people are born, live their lives, and die on that ship before it reaches it’s destination.”

Indeed, that was what I was aiming for. A ship that can last the time it takes to get significant payloads there.

What we will soon have is the ability to launch ~150 t to orbit at a very rapid rate. That has to be a path to new possibilities. I would think that there is a path to at least build a project over the next 250 years that can be launched there.

I’m with Frank above that this is probably bad news if confirmed, in particular the eccentricity. The good news would be confirmation of a planet accretion-friendly environment but a gas planet Saturn sized or smaller inside 2 AU with significant eccentricity is probably worst case, as moons would likely not be big enough (unless a large terrestrial world captured though even then the eccentricity would hinder habitability) and planets from 1 to 2 AU (A’s HZ) likely cleared out.

Here you have the real “The Real McCoy”! It operates near lightspeed and draws energy from the vacuum, straight out of Skunk Works: the popular name for Lockheed Martin’s Advanced Development Programs.

Semiconductor Space Drives | Charles Chase

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DW44J7jaGgs

2,121 views Aug 8, 2025 Tim Ventura Interviews

Warp Drive On A Chip? Former Lockheed Skunk Works RevTech Program head Charles Chase discusses diode-based propellantless space drives, ZPE generators, nanotech machining & antimatter shielding at the UnLAB.

Charles Chase has created a new type of propulsion based on the motive forces predicted to be generated from the interaction between vacuum fluctuations and asymmetric potentials such are found in Resonant Tunneling Diodes. Development would fundamentally change space propulsion since it operates without propellant with infinite ISP, and the total impulse is only limited by the lifetime of the device.

In this interview, we also discuss the work of Drs. Harold “Sonny” White and Garret Moddel using the Casimir effect to harness zero-point energy, in addition to Chase’ ideas for synthesizing ultra-heavy atoms in the periodic table’s theorized “island of stability”, which may generate anti-protons for use as an anti-matter shield.

Finally, we touch on Charles Chase’ patented Coherent Matter Wave Beam – a particle beam more powerful than a laser, capable of sub-nanometer machining next generation nanotech components.

Chase retired from Lockheed Martin in 2018 as a Senior Tech Fellow, a distinction reserved for the top 0.1% of technical talent in the corporation. His experience includes over 32 years at Lockheed Martin in aerospace systems R&D, including over 25 years at the prestigious Skunk Works division, where he built & led world class multi-disciplinary teams responsible for the conception, development, and market transition of transformative technologies.

After retirement, Chase co-founded the UnLAB, where he has continued developing breakthrough technologies, including executing research grants for DARPA/DSO, Office of Naval Research, NSF, and the Limitless Space Institute, collaborating with Stanford, Princeton, UCLA, and Technion among many others.

LINKS & RESOURCES:

The UnLAB (Official Website)

https://unlab.us/

Charles Chase (LinkedIn)

/ charles-chase-b2838937

Charles Chase: Jan 20 2022, Advanced Propulsion & Energy Conference

• https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_HHRlagr7cg

Systems and methods for generating coherent matter wave beams

https://patents.google.com/patent/US9502202B2/en

Coherent Matter Wave Beams 1000x stronger than Lasers – Frontier Science Research.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jd6KaEGH8JY

242 views Apr 29, 2025 #physicsexplained #futuretech #waves

Presentation by: Charles Chase – UnLAB LLC

at Shoshin Works event: • Convergence | US Deeptech, Energy and Sp…

Coherent matter wave beams, like coherent light beams (lasers), exhibit a synchronized wave behavior where all the particles in the beam are in phase. This coherence allows for phenomena like interference and diffraction, similar to what’s seen with light. Generating these beams with massive particles, however, poses challenges, as the phase of the particles must be manipulated without altering their energy.

Key Concepts:

Coherence:

Particles in a beam are in phase, meaning their wave functions are synchronized.

Matter Waves:

Particles, like atoms, exhibit wave-like properties due to de Broglie’s hypothesis.

Phase Manipulation:

Changing the phase of particles in a beam without altering their energy is a key challenge in generating coherent matter wave beams.

Interference and Diffraction:

Coherent matter waves can interfere and diffract, creating patterns similar to those seen with light.

By the time we build another huge space telescope or ground-based interferometer, we could send these probes to the Alpha Centauri system and Proxima Centauri and have the data back in less than 9 years.

I wish I could believe that.

Humanities focus should be on building larger and larger launch vehicles–use the brute force approach to establish infrastructure.

Perhaps breakthroughs can happen off-world that we cannot replicate this far down into a gravity well.

Even LEO isn’t enough.

I think the planet should be named Rigil Kent’ so as to avoid confusion.

Among other things, this a sudden and unexpected development. Unexpected in the sense of picking up the news for the day, but not in the sense of wondering if such a thing exists.

But it did mean reviewing work done decades ago about planetary system dynamics in binary star systems, particularly this one. There are plenty of investigations scattered around , of course. But here on Centauri Dreams was my own re-account of earlier papers

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2020/02/07/in-the-days-before-centauri-dreams-an-essay-by-wdk/

For the most part it was a re-account of dynamic simulations presented to the American Astronautical Society in 1997. Additionally, a group at the University of Toronto was doing similar, more detailed work, particularly for exoplanets systems out of the orbital plane. See the work of Paul Wiegart and Matt Holman.

But the pertinent point here is that these simulations show that planetary analogs to Earth, Mars and Venus will not orbit A or B in orbits with as little variation as

we experience. Over thousands of years, this new “Saturn” could have eccentricity near zero and then eccentricity greater 0.1 and the periapsis will complete a revolution in celestial space in accordance with that. Being out of the binary star plane will diminish the magnitude but not erase it.

Of course, if one examines one planet at a time ( as I was doing), the implications of several terrestrial planets doing these oscillations simultaneously was not addressed. Depending on an “initial condition”, assuming that they formed, they could have had run into catastrophic collisions early on or else prevailed an coalesced into large terrestrial planets like our own, somehow spacing themselves out.

Another possibility confronting us is that they end up in a big Saturn sized mass and nothing else left to tell the tale. And another possibility is that a planet or two remains in the “exo- Saturn” planet’s plane with sufficient spacing. Likely too hot or cold to make us happy.

For the terrestrial analog of the study mentioned above . orbiting in Alpha Cen A-B equatorial plane,

Ro = 1.2468 AU, Teff = 400o K, P= 486 days, P*=79.9 yrs.

Teff for the planet in this context is about Earth equivalent placement from the star or sun in terms of black body radiation from the sun’s surface.

A caption describing motion the Alpha Centauri Earth analog:

Centauri A Planet (R/Ro) max, min and period over ~100 Stellar Revolutions (~8000 terrestrial years) Midway, 4000 Earth years, the eccentricity reached

about 0.1 and the argument of periastron had rotated in space 180 degrees.

From there the cycle reversed coming back to the original values.

Planets farther from Alpha Cen A would experience more severe oscillations in their orbits and the it would breakdown in some no man’s land between the two stars. A chaotic path or perhaps expulsion. Alpha Centauri B analogs to Earth, since the star was cooler and less massive, these experienced less variation in

their orbital elements since they were more tightly bound to their primary.

Based on the Alpha Centauri A evidence, one could surmise that in early formation days, planetesimals might collide with each other due to such disturbances and build planets – or they might be prevented from constructing planets similar to terrestrial ones, because of the intensity of collisions. I am not sure if any of the above tilts the argument either way, however.

Now, evidently we have a large planet out of the stellar binary plane.

Reflecting on the above, there are number of possibilities.

1. The planet, if extant experiences similar oscillations, though likely

reduced in magnitude due to its inclination to the binary star system plane.

2. If the planet has a semi-major axis similar to the study test case planet, then the period would be about the same. JWST when it detected it, might have got most of its data at aphelion. The “exo-saturn” is presumed to be in an eccentric orbit with observation near 2 AU, but a period consistent with semi-major axis around

1.25 AU similar to my study case. Have to wonder what perihelion is like.

3. If the dynamics described above are valid, we would expect that over about

8000 years the eccentricity and and ascending node to cycle a “tenth” or so and 360 degrees respectively. If there are other planets in this plane, they would behave similarly. But there won’t be room for everybody and the gas giant types has the best chance to survive.

4. Then there’s the inclination to the binary plane. There are probably arguments about binaries that allow or prohibit stellar rotational axes tilt from or obliquity to the binary orbital plane. But it would be nice to have some verification for what it is. If the rotational or polar axis of Alpha Centauri A is perpendicular to the plane, then its only known planet has a lot of explaining to do. Maybe even about what happened to its long ago friends.

With an 0.1 eccentricity, for an average orbital distance of 150 million km, the perihelion is 135 million km, and aphelion 165 million km, neither as small as Venus’ orbit, nor as large as Mars’.

What this would do to habitability is an interesting question. As this occurs in a terrestrial year, would the temperature inertia maintain an average terrestrial climate, but with the equivalent of very hot summers and very cold winters? If the eccentricty changes over millennia, are there more stable climates suitable for life, or does the climate keep cycling through ice ages and interglacials? How much does geography affect this?

An interesting system for speculative biology and evolution.

A.T.,

As you describe the environmental conditions for life as we know it would be interesting enough. We can see more variety and extremes already – and then there are such arbitrary additions such as gravity, atmospheric constituents

and density at a surface, tectonics…

But scratching the surfaces of planets we have discovered thus far, it looks like their geological, atmospheric and subsequent biological circumstances are likely much more diverse, different and complicated than we had suspected or imagined.

But any sentience out there might view us within the same framework – as very odd or having taken unexpected turns.

Oh, to watch nature programs with future naturalists of the David Attenborough ilk, showing videos and describing the lifestyles of animals and plants on some very unusual planets. They might make prehistoric animals and dinosaurs seem quite tame in comparison.

Comparing and contrasting with terrestrial life to show the evolutionary divergences and convergences would be fascinating, even if the underlying molecular biology proved rather similar to Earth’s.

Whether in the solar system or outside it as with Alpha Centauri, I have a suspicion that life should not be ruled out at some layers of pressure and temperature. Cephalopods can and fish can be encountered at great depths.

Volcanic venting gives some assist, but perhaps bands and belts can substitute.

Of course, our problem with giant planets in the solar system is access to such layers. But in engineering terms it is not as difficult as traveling to the nearest star. Startlingly, we have already solved the entry descent problem with the

Galileo mission probe.

On the other hand, gas giant planets for one reason or another have tended to prosper in terms of moons. And if Alpha Centauri A reflectance data might be a little ambiguous right now, maybe it actually is smaller – and has a ring.

Three new space telescopes are expected to provide better data on the planets around Alpha Centauri within the next 20 months:

1. **Toliman** https://toliman.space/

2. **Xuntian Space Telescope** https://newspaceeconomy.ca/2025/06/30/what-is-the-xuntian-space-telescope-and-why-is-it-important/

3. **Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope** https://astrobiology.com/2024/05/nancy-grace-roman-space-telescopes-planet-hunting-coronagraph-update.html

I believe Toliman may be the first to yield results, as it is likely to be launched before the others and is primarily focused is on the Alpha Centauri A-B system.

Paul, could you please check for updates on the Toliman space telescope, including its possible launch date, planned system observations, and any other interesting details about this 12.5-centimeter (5-inch) telescope? Thank you in advance!

I found this on Interstellar Updates, a very interesting article and a lot deeper analysis:

A Cost-Effective Search for Extraterrestrial Probes in the Solar System.

Beatriz Villarroel

https://academic.oup.com/mnras/advance-article/doi/10.1093/mnras/staf1158/8221885

This is bad news for habitable planets around Alpha Centauri A surely.

On the other hand, they have not seen a gas giant around “B”, and I think it was “B” that had the highest hope of a habitable planet in the first place ?

Some quick thoughts:

First off I’m dubious of this finding due to the fact that planets this size were supposedly ruled out by RV measurements.

Given the angle between Centauri A & B’s equatorial plane and their co-orbital plane, the Kozai effect (ZKL effect)–wherein planetary bodies oscillate in eccentricity and orbital inclination–this would be expected to play a big part in planetary orbital dynamics. The first paper goes into some detail on this and this would explain the planet’s orbital eccentricity.

(A formation scenario would go like this: initially, multiple Neptunian-sized planets would form–this seems to be the size that forms around G class stars. They would then migrate inward. But as binary’s form, the two stars migrate inward and their co-orbital eccentricity increases, so this would ramp up the ZKL effect on the planets causing them to collide and coalesce, forming a body of sufficient mass to acquire a massive Hydrogen envelope before the planetary nebula dispersed.)

Finally, I notice that James Cameron’s Avatar series is set on Pandora, an Earth-sized moon around a gas giant in the habitable zone Alpha Centauri A. If you read the details on the Wiki page https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fictional_universe_of_Avatar, you’ll notice a close match with the supposed planet A Centauri b. Maybe, he knows something we don’t.

More on Polyphemus…

https://m.youtube.com/watch?si=I4urWvWZrJjp1f6-&fbclid=IwQ0xDSwMHWjJleHRuA2FlbQIxMQABHt-MBr_fRXXTPJX6ME9YgxGuWttep0GfUydajVDV3wSNdP7g_b5_5atyA8x1_aem_ztFd7usszwmaiJECGvWpNA&v=7ioJvlWBg58&feature=youtu.be

The problem with the gas giant idea in the Gas giant around Alpha Centauri A is that we use single star system accretion disk model and not a double star system which can change. Double stars which are in close obits or are very far apart have planets, but there are some model especially the Centauri system where it is a lot more difficult to have planets if not impossible. A and B Centauri is one of those systems where the stars are too close and due to tidal forces limit the size of the planets? The idea is that in such a system where the stars are about the Sun distance to Saturn don’t have any planets because the angular momentum of the other star grabs all the dust, and gas to make any planets. I mentioned this on another Centauri dreams article about the Centauri system. I read it in a older book, One Hundred Billion Suns by Rudolf Kippenhahn. So far his idea is valid if we look at the A and RV methods. of detecting planets which is why I don’t like distortion in the images since we can see what we want to see, but not what is actually there.

It would be convenient to have planets there especially an Earthlike one in the life belt, but I accept the possibility and high probability that future telescope technology will rule that system out.

I think Wiegert and Holman did the first major analysis on habitable zone planet orbits at Alpha Centauri A and B back in the 1990s. Planets are feasible out to 2 AU or something like that around each– I don’t have the paper in front of me, but it’s all in the archives here. What bothers me is the elliptical orbit around the possible gas giant, which could disrupt inner orbits.

I hope we built the origami starshade which would allow us to directly image some explanets and get any spectra with the JWST. It would be worth it.

Closing in on Centauri A and B with Astrometry

by Paul Gilster | Apr 28, 2021 | Exoplanetary Science | 10 comments

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2021/04/28/closing-in-on-centauri-a-and-b-with-astrometry/

huh, is this even compatible with radial velocity limits we had on planets in alpha cen? I seem to recall an article on this very blog, something like 15 years ago, which I thought excluded jovians around there in the HZ already? I remember thinking Avatar system was unrealistic on that basis. Now this is admittedly somewhat smaller, eccentric and prob somewhat further out, is that all that’s going on and a planet was just outside our exclusion limits back then, or is my memory failing me, or was that just a wrong study?

Could a world like Pandora from the Avatar franchise exist in the Alpha Centauri system? It is a moon that does circle a gas giant planet, after all.

Well…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pJ5L6hLD4KU