Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Fine-Tuning Mechanisms for Water Delivery

We’ve long been interested in how the Earth got its oceans, with possible purveyors being comets and asteroids. The idea trades on the numerous impacts that occurred particularly during the Late Heavy Bombardment some 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago. Tuning up our understanding of water delivery is important not only for our view of our planet’s development but for its implications in exoplanet systems with a variety of different initial conditions.

Image: This view of Earth’s horizon was taken by an Expedition 7 crewmember onboard the International Space Station, using a wide-angle lens while the Station was over the Pacific Ocean. Credit: NASA.

But the picture becomes more complex when we compare regular hydrogen atoms (one proton, one electron) with ‘heavy hydrogen,’ or deuterium atoms. The latter have a neutron in addition to a proton in the nucleus. A recent paper in the Journal of Geophysical Research digs into isotope ratios, the ratio of deuterium to ordinary hydrogen atoms, commonly referred to as the D/H ratio. One reason asteroids are favored by some scientists as the likely source of the bulk of Earth’s water is that asteroidal water has a D/H in the neighborhood of 140 parts per million. Contrast that with cometary water, which runs from 150 ppm to as high as 300 ppm.

When we examine Earth’s oceans, we find a D/H ratio close to that found in asteroids. The new study, from Jun Wu and colleagues at the School of Molecular Sciences and School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University, takes aim at the asteroid explanation, not by way of discounting it but rather of finding other sources making a contribution to Earth’s water.

“It’s a bit of a blind spot in the community,” said ASU’s Steven Desch, a co-author of the new study. “When people measure the [deuterium-to-hydrogen] ratio in ocean water and they see that it is pretty close to what we see in asteroids, it was always easy to believe it all came from asteroids.”

We are learning, however, that too uncritical an acceptance of D/H ratios may oversimplify the issue. For the hydrogen in Earth’s oceans is not necessarily representative of hydrogen deeper inside the planet, where D/H ratios close to the boundary between the core and mantle show considerably less deuterium. This may indicate a non-asteroidal source for at least some of the hydrogen.

Another telling point is that helium and neon, showing isotopic signatures inherited from the original solar nebula, have also been found in Earth’s mantle. Contrasting hydrogen at the core-mantle boundary with what we see in Earth’s oceans and factoring in these noble gases may change our thinking. The Wu study considers the formation of the planets in the earliest days of the Solar System, when small, often colliding planetary embryos up to the size of Mars went through gradual planetary accretion.

The new model works like this: As larger embryos formed largely from water-laden asteroids, they began to develop into planets. On Earth, decaying radioactive elements melted iron within the emerging world, pulling in asteroidal hydrogen and sinking to form a core. Collisions among planetesimals would meanwhile have created enough energy to melt the surfaces of the larger embryos like the Earth into magma oceans.

Hydrogen and noble gases from the solar nebula would be drawn in to create an early atmosphere. The nebular hydrogen, lighter than asteroidal hydrogen, would have dissolved into the molten iron of the magma ocean, eventually being drawn into the mantle, along with hydrogen from other sources.

What the authors argue is that this process created a slight enrichment of hydrogen in the molten iron and left a higher ratio of deuterium behind in the magma (the process is called isotopic fractionation). Hydrogen is attracted to iron, while the heavier isotope, deuterium, less attracted to iron, would have remained in the magma which would eventually become Earth’s mantle. We would end up with lower D/H ratios in the core than in the mantle and oceans. The authors argue that while most of Earth’s water is asteroidal, some of it did in fact come from the solar nebula.

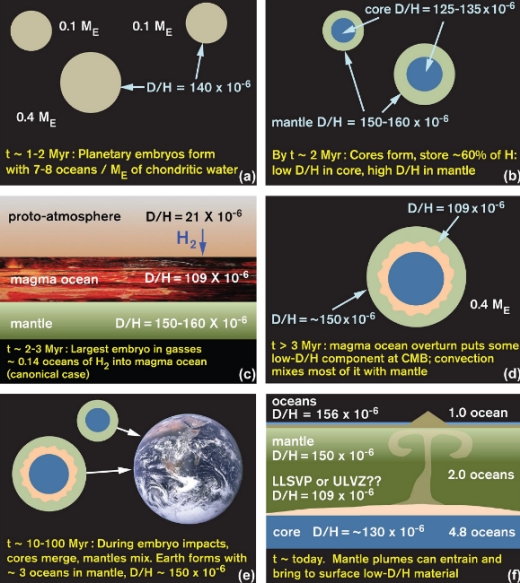

The process is complex, and also takes in impacts from smaller embryos and other objects that continued to add water and mass until Earth reached its final size. The authors provide this synopsis as their caption for Figure 1 (above), which I’ll reproduce verbatim but break into sections for reasons of readability:

- (a) Earth accreted from embryos with chondritic [asteroidal] levels of water concentrations and D/H ratios.

- (b) These embryos differentiated and stored relatively light hydrogen in their cores, raising the D/H of hydrogen in their mantles.

- (c) The largest embryo accreted a proto-atmosphere and sustained a magma ocean into which nebular hydrogen diffused.

- (d) The largest embryo’s magma ocean crystallized and overturned, mixing light hydrogen into the mantle, but incompletely.

- (e) As smaller embryos were accreted, their mantles joined the proto?Earth’s mantle, and their cores merged with the proto?Earth’s core.

The result is:

- (f) Earth’s mantle today contains approximately three oceans of water in its mantle and surface, with average D/H ? 150 × 10?6, and ~4.8 oceans’ worth of hydrogen in its core, with D/H ? 130 × 10?6. Mantle plumes can sample low?D/H material from the core?mantle boundary.

Wu says this: “For every 100 molecules of Earth’s water, there are one or two coming from [the] solar nebula.” But we now see the potential for including gas left over from the formation of our Solar System in the question of water delivery and accumulation. In other stellar systems where water-bearing asteroids may not be as abundant, this implies that water could still be in place from the system’s own stellar nebula. Wu adds: “This model suggests that the inevitable formation of water would likely occur on any sufficiently large rocky exoplanets in extrasolar systems. I think this is very exciting.”

The paper concludes:

Our comprehensive model for the origin of Earth’s water considers, for the first time, the effects of isotopic fractionation as hydrogen dissolved into metal and was sequestered into the core. Based on the behaviors of proxies, we consider it likely that the D/H ratio of the core is ~10% lighter than the mantle. We hypothesize that Earth accreted a few to tens of oceans of water from chondrites, mostly carbonaceous chondrites. Drawing on the latest theories of planet formation, which argue for rapid (<2 Myr) formation of planetary embryos, we favor ingassing of a few tenths of an ocean of solar nebula hydrogen into the magma oceans of the embryos that formed Earth.

The paper is Wu et al., Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 09 October 2018 (full text).

On the Earliest Stars

If you’ve given some thought to the Fermi question lately — and reading Milan ?irkovi?’s The Great Silence, I’ve been thinking about it quite a bit — then today’s story about an ancient star is of particular note. Fermi, you’ll recall, famously wanted to know why we didn’t see other civilizations, given the apparent potential for our galaxy to produce life elsewhere. Now a paper in The Astrophysical Journal adds punch to the question by making the case that the part of the galaxy in which we reside may be older than we have thought.

Finding that our Sun is younger than many nearby stars, an issue that Charles Lineweaver (Australian National University), among others, has examined, would allow even more time for civilizations to have emerged in the galactic neighborhood. But let’s now leave Fermi behind to look at the tiny star that prompts these ruminations (and to be sure, the paper on this star makes no mention of Fermi, but does tell us something quite interesting about the early cosmos).

Discovered by Kevin Schlaufman (Johns Hopkins University), 2MASS J18082002–5104378 B is the smaller of a binary pair that orbit a common barycenter. While the primary had been previously discovered, it was up to Schlaufman and team to uncover the far more interesting companion.

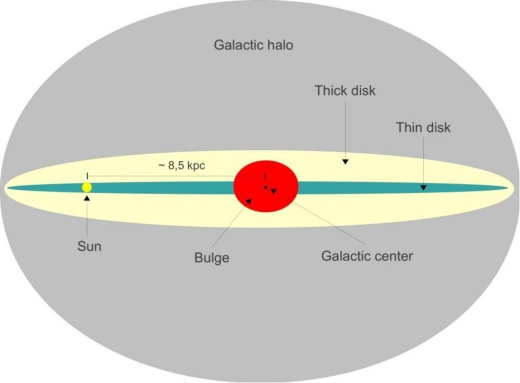

Schlaufman used data from the Magellan Clay Telescope, Las Campanas Observatory and the Gemini Observatory in finding and characterizing this star. What distinguishes 2MASS J18082002–5104378 B is its size, metallicity and age. On the latter, Schlaufman believes it could be as little as a single generation removed from the Big Bang itself, and the paper pegs its age at approximately 13.5 billion years. We’ve discovered other ancient stars with low metal content, but this one is located in the Milky Way’s thin disk, that part of the galaxy in which we reside. Hence the issue of the age of local stars, as the paper recounts:

Given its thin disk orbit, the 13.535 ± 0.002 Gyr age of the 2MASS J18082002–5104378 system provides a lower limit on the age of the thin disk. Similarly old but not quite as metal-poor stars have also been seen on thin disk orbits (e.g., Casagrande et al. 2011; Bensby et al. 2014). This is somewhat older than the 8–10 Gyr age of the thin disk suggested by classical studies of field stars (Edvardsson et al. 1993; Liu & Chaboyer 2000; Sandage et al. 2003), the white dwarf luminosity function (e.g., Oswalt et al. 1996; Leggett et al. 1998; Knox et al. 1999; Kilic et al. 2017), and the ages of the oldest disk open clusters Berkeley 17 and NGC 6791 (e.g., Krusberg & Chaboyer 2006; Brogaard et al. 2012).

Image: This edge-on diagram of the Milky Way shows the thin disk in green. Credit: Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

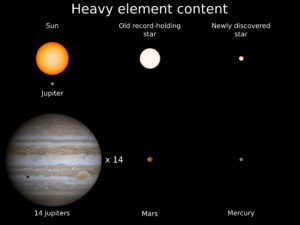

We are talking about a star with a content of metals roughly the same as the planet Mercury. Contrast that with the Sun, whose heavy element content is equal to approximately 14 Jupiters.

2MASS J18082002–5104378 B (here’s hoping it gets a new moniker, perhaps ‘Schlaufman’s Star’) is the lowest-mass ultra metal-poor star currently known. Yet despite its extreme age and low metallicity, it is found in the thin disk, and in fact is the most metal-poor star yet found that is part of the thin disk. We would expect stars forming not long after the Big Bang to be low in metals, given that hydrogen, helium and trace lithium are all they had to work with. It would be later stellar generations that could form with the heavier elements these early stars produced in their cores, seeding the cosmos with metals through supernovae explosions.

Call that first generation Population III stars, which when first modeled by researchers produced stars far more massive than the Sun, giant objects that should form as single stars in isolation. Later models dropped the range of mass to as low as 10 solar masses but also extended it on the high end. Low-mass Population III stars only recently began to be considered when the issue of fragmentation began appearing in numerical simulations. The discovery of 2MASS J18082002–5104378 B makes the case for the emergence of such stars.

From the paper:

We use models of protostellar disks around both UMP [low-mass ultra metal-poor] and Pop III protostars plus scaling relations for the fragment mass and migration time to argue that the existence of the low-mass UMP star 2MASS J18082002–5104378 B and the extremely metal-poor (EMP) brown dwarf HE 1523–0901 B discovered by Hansen et al. (2015) implies the survival of solar-mass fragments around Pop III stars…

Thus we may be looking at a new observable that can take us back to conditions at the earliest era of star formation:

Whereas fragmentation at the molecular core scale will likely lead to massive binary stars, the emergence of gravitationally bound solar-mass clumps in protostellar disks via gravitational instability has the potential to produce low-mass Pop III stars that may be observable in the Milky Way.

Image: The new discovery is only 14% the size of the Sun and is the new record holder for the star with the smallest complement of heavy elements. It has about the same heavy element complement as Mercury, the smallest planet in our solar system. Credit: Kevin Schlaufman/JHU.

Thus far about 30 stars considered ultra metal-poor have been identified, all of roughly the Sun’s mass, but 2MASS J18082002–5104378 B is only 14 percent of the Sun’s mass. The mass, incidentally, was determined by radial velocity methods, examining the wobble of the primary star. Backing out to the wider picture, our view of the earliest stars as extremely massive objects, unobservable to us because they would have burned quickly and died, has to be modified to include low-mass stars that can, at least in some situations, emerge, as 2MASS J18082002–5104378 B did, burning for long lifetimes indeed. Says Schlaufman:

“If our inference is correct, then low-mass stars that have a composition exclusively the outcome of the Big Bang can exist. Even though we have not yet found an object like that in our galaxy, it can exist.”

The paper is Schlaufman et al., “An Ultra Metal-poor Star Near the Hydrogen-burning Limit,” Astrophysical Journal Vol. 867, No. 2 (5 November 2018). Abstract / preprint.

SETI in the Infrared

One of the problems with optical SETI is interstellar extinction, the absorption and scattering of electromagnetic radiation. Extinction can play havoc with astronomical observations coping with gas and dust between the stars. The NIROSETI project (Near-Infrared Optical SETI) run by Shelley Wright (UC-San Diego) and team is a way around this problem. The NIROSETI instrument works at near-infrared wavelengths (1000 – 3500 nm), where extinction is far less of a problem. Consider infrared a ‘window’ through dust that would otherwise obscure the view, an advantage of particular interest for studies in the galactic plane.

Would an extraterrestrial civilization hoping to communicate with us choose infrared as the wavelength of choice? We can’t know, but considering its advantages, NIROSETI’s instrument, mounted on the Nickel 1-m telescope at Lick Observatory, is helping us gain coverage in this otherwise neglected (for SETI purposes) band. I had the chance to talk to Dr. Wright at one of the Breakthrough Discuss meetings in Palo Alto, where she made a fine presentation on the subject. Since then my curiosity about infrared SETI has remained high.

Meanwhile, at MIT…

Then this morning I came across graduate student James Clark, who has just published a paper on interstellar beacons in the infrared in the Astrophysical Journal. Working at MIT’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Clark is not affiliated with NIROSETI. He’s wondering what it would take to punch a signal through to another star, and concludes that a large infrared laser and a telescope through which to focus it would be the tools of choice.

The goal: An infrared signal at least 10 times greater than the Sun’s natural infrared emissions, one that would stand out in any routine astronomical observation of our star and demand further study. Clark believes that a 2-megawatt laser working in conjunction with a 30-meter telescope would produce a signal easily detectable at Proxima Centauri b, while a 1-megawatt laser working through a 45-meter telescope would produce a clear signal at TRAPPIST-1.

But nearby stars are just the beginning, for in Clark’s view, either of these setups would produce a signal that could be detected up to 20,000 light years away, almost to galactic center. All of this may remind you of Philip Lubin’s work, recently described here, on laser propulsion. Depending on the system in play, one of Lubin’s DE-STAR 4 beams would be observed as the brightest star in the sky from 1000 light years away (see Trillion Planet Survey Targets M-31 for more on this). The NIROSETI website makes the same observation about laser visibility:

The most powerful laser beams ever created (e.g. LFEX) can produce optical pulses with 2 petawatts (2.1015W) peak power for an incredibly short duration, approximately one picosecond. Such lasers would outshine our sun by several order of magnitudes if seen by a distant receiver. It can be shown that strong pulsed signals at nanosecond (or faster) intervals can be distinguishable from any known astrophysical sources.

![]()

Image: An MIT study proposes that laser technology on Earth could emit a beacon strong enough to attract attention from as far as 20,000 light years away. Credit: MIT.

The kind of system Clarke is talking about is not beyond our capabilities even now:

“This would be a challenging project but not an impossible one,” Clark says. “The kinds of lasers and telescopes that are being built today can produce a detectable signal, so that an astronomer could take one look at our star and immediately see something unusual about its spectrum. I don’t know if intelligent creatures around the sun would be their first guess, but it would certainly attract further attention.”

In terms of current capabilities, we can think about Clark’s 30-meter telescope in relation to plans for telescopes as huge as the 39-meter European Extremely Large Telescope, now under construction in Chile, or the likewise emerging 24-meter Giant Magellan Telescope. How and where to build such a laser is the same sort of issue now being analyzed by Breakthrough Starshot, which conceptualizes a series of small lightsail missions to nearby stars using laser beaming. Caveats include safety issues for both humans and spacecraft equipment. Clark suggests the far side of the Moon would be the ideal place for such an installation.

With METI (Messaging to Extraterrestrial Intelligence) continuing to be controversial, to say the least, whether or not we would ever choose to build an infrared laser as an interstellar beacon is up for question. But Clark’s analysis takes in the question of whether today’s technologies could detect such a signal if a civilization elsewhere put it into play and tried to communicate with us. As we’ve seen in other discussions of interstellar beacons, detection is highly problematic.

“With current survey methods and instruments, it is unlikely that we would actually be lucky enough to image a beacon flash, assuming that extraterrestrials exist and are making them,” Clark says. “However, as the infrared spectra of exoplanets are studied for traces of gases that indicate the viability of life, and as full-sky surveys attain greater coverage and become more rapid, we can be more certain that, if E.T. is phoning, we will detect it.”

We don’t know whether E.T. does astronomical surveys, but we know we do, and we are rapidly moving toward the study of small, rocky exoplanets through the spectra of their atmospheres. Thus Clark’s paper could be seen as a reminder to astronomers that an unusual signal could lurk within their infrared data, one that we should at least be aware of and prepared to analyze. A conversation between nearby stars at a data rate of a few hundred bits per second could eventually result.

The paper is Clark, “Optical Detection of Lasers with Near-term Technology at Interstellar Distances,” Astronomical Journal Vol. 867, No. 2 (5 November 2018). Abstract.

Bennu Coming into Focus

Following a week when we learned of the end of both Kepler and Dawn, let’s turn to a mission that is just coming into its own. The earliest images of target asteroid 101955 Bennu from OSIRIS-REx have been tightened by computer algorithm to heighten their resolution. The mission plan here is to examine the small object (approximately 500 meters in mean diameter) and return samples to Earth in 2023.

More than a few people have reacted to the similarity in shape between this asteroid, a carbonaceous (C-type) Earth-crossing object in the Apollo group of near-Earth asteroids, and 162173 Ryugu, now under active exploration by the Japanese Hayabusa2 mission. Here we’re looking at Bennu through the OSIRIS-REx PolyCam, one of three cameras aboard the spacecraft, from a distance of 330 kilometers. The image is a combination of eight images taken by PolyCam that have been combined to cancel out the asteroid’s rotation and produce a high-resolution result.

Of the comparison to Ryugu, Julia de León (Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias – IAC) says this:

“The fact that the Japanese mission has reached its target a little ahead of us turns out to be extremely interesting, as we can now interpret our results and compare to the results obtained by another mission almost on real time.”

Image: This “super-resolution” view of asteroid Bennu was created using eight images obtained by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft on Oct. 29, 2018 from a distance of about 330 km. The spacecraft was moving as it captured the images with the PolyCam camera, and Bennu rotated 1.2 degrees during the nearly one minute that elapsed between the first and the last snapshot. The team used a super-resolution algorithm to combine the eight images and produce a higher resolution view of the asteroid. Bennu occupies about 100 pixels and is oriented with its north pole at the top of the image. Date Taken: Oct. 29, 2018. Instrument Used: OCAMS (PolyCam). Credit: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona.

The team from the IAC, which functions as part of the Image Processing Working Group (IPWG) for the OSIRIS-REx mission, is examining the early imagery from Bennu as an initial step in calibrations for comparison with later, higher-resolution images taken with color filters. In December, images from the spacecraft’s MapCam will begin coming in, putting those filters to work. The color maps thus generated will be used to break down the geographical distribution of silicates and other materials on the asteroid. And, of course, they will also play into the selection of a landing site from which a sample will be collected and returned to Earth.

OSIRIS-REx executed its third asteroid approach maneuver (AAM-3) on October 29, a set of thruster burns designed to slow the craft relative to Bennu from approximately 5.2 m/sec to .11 m/sec. The maneuver, verified by tracking data and telemetry, was designed to maximize the collection of high-resolution images as the spacecraft closes on the target. Another burn, the fourth in a series that began on October 1, will be executed on November 12, adjusting the craft’s trajectory for arrival at a position some 20 kilometers from Bennu on December 3.

And here’s another interesting image, a look at both Bennu and Jupiter, as seen by the OSIRIS-REx Polycam. The shot of Bennu was taken on October 22 of this year, with Bennu some 3,650 kilometers away, while the Jupiter image was captured on February 12, 2017 at a distance of 673 million kilometers. Notice the clear spherical shape of Jupiter as compared to the diamond-shaped Bennu, a shape predicted by ground-based radar observations.

Image: When these images were taken, Bennu was about five times closer to the Sun than Jupiter was, so the asteroid was receiving significantly more sunlight. If Bennu and Jupiter were equally reflective, the asteroid would appear about 25 times brighter in this image due to its proximity to the Sun. But Bennu’s surface is so dark (only reflecting about 3 to 4 percent of the incoming sunlight) that it appears darker than Jupiter despite being much closer to the Sun. Credit: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona.

Carbonaceous C-type asteroids, as the image makes clear in this case, are low in albedo, presumably because of the large amount of carbon mixing with surface rocks and minerals.

If you’re tracking this mission closely, be aware of email updates that are available and check Twitter @OSIRISREx, Instagram or Facebook for more.

How many times is too many times to ask #AreWeThereYet on a single trip? Asking for a friend (who is now only a couple hundred kilometers from #asteroid Bennu)…

More on my whereabouts: https://t.co/rACre4nDe4 pic.twitter.com/tJaMcHw6qP

— NASA's OSIRIS-REx (@OSIRISREx) November 5, 2018

Farewell to Dawn

It seems to be a week for endings. Following the retirement of the wildly successful Kepler spacecraft, we now say goodbye to Dawn following an extraordinary eleven years that took us not only to orbital operations around Vesta but then on to detailed exploration of Ceres. The spacecraft ran out of hydrazine, with the signal being lost by the Deep Space Network during a tracking pass on Wednesday. No hydrazine means no spacecraft pointing, vital in keeping Dawn’s antenna properly trained on a distant Earth.

I immediately checked to see if mission director and chief engineer Marc Rayman had gotten off a post on his Dawn Journal site, but he really hasn’t had time to yet. It will be interesting to see what Dr. Rayman says, and it’s appropriate here to thank him for the continuing updates and insights he provided throughout the Dawn mission. Keeping space exploration in front of the public is essential for continuing funding of deep space robotic missions, as both the Dawn and New Horizons team clearly understand (and there is much ahead for New Horizons!)

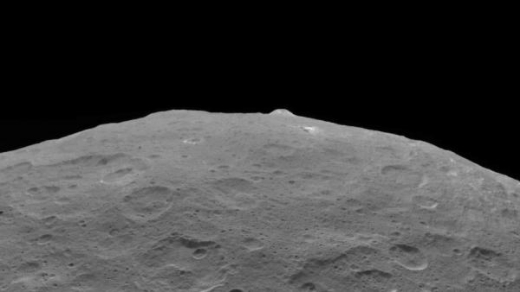

Image: This photo of Ceres and one of its key landmarks, Ahuna Mons, was one of the last views Dawn transmitted before it completed its mission. This view, which faces south, was captured on Sept. 1 at an altitude of 3570 kilometers as the spacecraft was ascending in its elliptical orbit. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA.

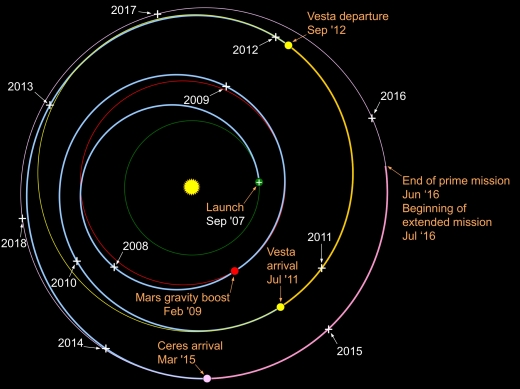

The ability to orbit one target, move on to another and subsequently establish an orbit there is a demonstration of what ion engines can do, and a reminder of how significant the Deep Space 1 mission was in terms of testing these technologies. If DS1 established ion propulsion as a viable tool, Dawn took it to the next level, highlighting the kinds of exploration that may lie ahead as we contemplate missions to multiple Kuiper Belt objects (see Game-changer: A Pluto Orbiter and Beyond). Ambitious missions grow out of the gentle, efficient thrust of ion engines.

Ponder this: The orbiters we’ve sent to Mars had to burn their engines for orbital insertion. Consider something on the order of 300 kilograms of propellant for conventional rocketry to meet this requirement. Dawn could make the same change in speed (about 1000 meters/second) using fewer than 30 kilograms of xenon. But of course we wouldn’t use ion engines for this purpose. Ion engines demand patience: It would take Dawn three months to achieve this result while conventional engines in our orbiters complete this maneuver in 25 minutes. But missions with multiple targets or complex operations in deep space are suited to engines like Dawn’s, which accumulated 2,141 days (5.9 years) of thrust time in the course of its travels.

Describing Dawn’s changing trajectories and the intricate gravitational dance they involved, Rayman wrote this paean to ion propulsion in his Dawn Journal:

Without that technology, NASA’s Discovery Program would not have been able to afford a mission to explore the exotic world in such detail. Dawn has long since gone well beyond that. Having discovered so many of Vesta’s secrets, the adventurer left it behind. No other spacecraft has ever escaped from orbit around one distant solar system object to travel to and orbit still another extraterrestrial destination. From 2012 to 2015, the stalwart craft reshaped and tilted its orbit even more so that now it is identical to Ceres’. Once again, that was essential to accomplishing the intricate celestial choreography in which the behemoth reached out with its gravity and tenderly took hold of the spacecraft. They have been performing an elegant pas de deux ever since.

And now the mission is over, though the spacecraft will remain in Ceres orbit for at least twenty years, and mission engineers believe with 99 percent confidence that its orbit will last at least 50 years, keeping planetary protection protocols in place for the near future. As we look back, consider Dawn’s accomplishments. It was the first spacecraft to orbit a body between Mars and Jupiter, the first to visit a dwarf planet and the first to orbit two destinations beyond Earth.

Image: Dawn’s interplanetary trajectory (in blue). The dates in white show Dawn’s location every Sept. 27, starting on Earth in 2007. Note that Earth returns to the same location, taking one year to complete each revolution around the Sun. When Dawn is farther from the Sun, it orbits more slowly, so the distance from one Sept. 27 to the next is shorter. Credit: NASA/JPL.

“In many ways, Dawn’s legacy is just beginning,” said principal investigator Carol Raymond at JPL. “Dawn’s data sets will be deeply mined by scientists working on how planets grow and differentiate, and when and where life could have formed in our solar system. Ceres and Vesta are important to the study of distant planetary systems, too, as they provide a glimpse of the conditions that may exist around young stars.”

Dawn’s discoveries at Vesta and Ceres have been described before in these pages, but we’ll track new conclusions from Dawn’s datasets well into the future. For now, I’m simply thinking about Dawn’s beginnings and all that has happened since. Congratulations to the entire team.

Image: Dawn climbs to space on Sept. 27, 2007, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. Dawn launched at dawn (7:34 am EDT). Credit: KSC/NASA.

The Stripes of Dione

Usually when we talk about outer planet moons with oceans, we’re looking at Jupiter’s Europa, and Saturn’s Enceladus. But evidence continues to mount for oceans elsewhere. In the Jupiter system alone, Callisto and Ganymede are likewise strong candidates, while Saturn’s Titan probably has a layer of liquid water. Pluto’s moon Charon may possess an ocean of water and ammonia, to judge from what appears to be cryovolcanic activity there. At Neptune, Triton’s high-inclination orbit should produce plenty of tidal heating that may support a subsurface ocean.

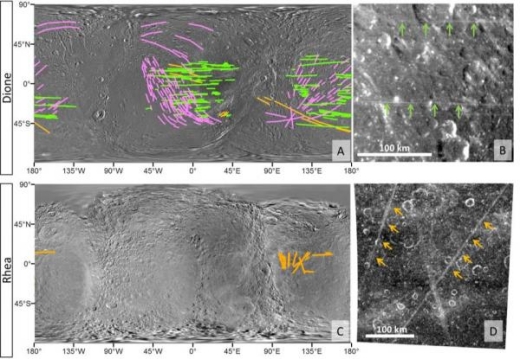

Let’s pause, though, on another of Saturn’s moons, Dione. Here we have evidence from Cassini that this world, some 1120 kilometers in diameter and composed largely of water ice, has a dense core with an internal liquid water ocean, joining Enceladus in that interesting system. But what engages us this morning is not liquid water but a set of straight, bright stripes discovered on the surface and discussed in a new paper from Alex Patthoff (Planetary Science Institute) and Emily Martin (Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, Smithsonian Institution).

The term being used for these lines is linear virgae, linear ‘stripes’ of color, that are apparently the result of interactions with Saturn’s rings and, possibly, the co-orbital moons Helene and Polydeuces (the latter follows Dione at its trailing Lagrangian point, the former orbiting at the leading L4 Lagrangian point).

“The evidence preserved in the linear virgae has implications for the orbital evolution and impact processes within the Saturnian system,” says Patthoff. “Plus, the interaction of Dione’s surface and exogenic material has implications for its habitability and provides evidence for the delivery of ingredients that may contribute to the habitability of ocean worlds in general.”

Image: Distribution of linear virgae on Dione and Rhea. Shown are the distribution of linear virgae (green) crater rays (pink) and candidate linear virgae (orange) a. Global distribution of linear virgae, crater rays, and candidate linear virgae on Dione. b. Detailed view of linear virgae (green arrows) on Dione. Image No. N1649318802 centered at 22°W, 10°N. c. Global distribution of candidate linear virgae on Rhea. d. Detailed view of candidate linear virga. Credit: A) Basemap from Roatsch et al, 2008. B) Image No. N1649318802. C) Basemap from Roatsch et al, 2012. D) Image No. N1673420688.

The linear virgae on Dione range between 10 and hundreds of kilometers in length and less than 5 kilometers in width, showing up as substantially brighter than the surrounding terrain. Interestingly, they’re also parallel and appear to overlay other surface features, an indication of their relative youth compared to surrounding topography. Patthoff again:

“Their orientation, parallel to the equator, and linearity are unlike anything else we’ve seen in the solar system. If they are caused by an exogenic source, that could be another means to bring new material to Dione. That material could have implications for the biological potential of Dione’s subsurface ocean.”

Thus we have another potential habitat for biology beneath an icy moon’s crust. Cassini imagery showed inactive fractures at Dione similar to those found at Enceladus, and the spacecraft’s magnetometer also detected a faint particle stream coming from the moon. In 2013, Noah Hammond (Brown University) and colleagues examined the Janiculum Dorsa mountain and ridgeline in Cassini data, finding that the moon’s crust seemed to have flexed beneath the mountain, an indication of a subsurface ocean and warm crust at least at the time the area formed. Why Enceladus is so active in comparison to Dione is an open question.

Image: Although Dione (near) and Enceladus (far) are composed of nearly the same materials, Enceladus has a considerably higher reflectivity than Dione. As a result, it appears brighter against the dark night sky. The surface of Enceladus (504 kilometers across) endures a constant rain of ice grains from its south polar jets. As a result, its surface is more like fresh, bright, snow than Dione’s (1123 kilometers across) older, weathered surface. As clean, fresh surfaces are left exposed in space, they slowly gather dust and radiation damage and darken in a process known as “space weathering.” This view looks toward the leading hemisphere of Enceladus. North on Enceladus is up and rotated 1 degree to the right. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Sept. 8, 2015. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

The paper is Martin & Patthoff, “Mysterious Linear Features Across Saturn’s Moon Dione,” Geophysical Research Letters 15 October 2018 (abstract). The Hammond paper is “Flexure on Dione: Investigating subsurface structure and thermal history,” Icarus Vol. 223, Issue 1, (March 2013), pp. 418-422 (abstract).